Abstract

Type II Chaperonin Containing TCP-1 (CCT, also known as TCP-1 Ring Complex, TRiC) is a multi-subunit molecular machine thought to assist in the folding of ∼10% of newly translated cytosolic proteins in eukaryotes. A number of proteins folded by CCT have been identified in yeast and cultured mammalian cells, however, the function of this chaperonin in vivo has never been addressed. Here we demonstrate that suppressing the CCT activity in mouse photoreceptors by transgenic expression of a dominant-negative mutant of the CCT cofactor, phosducin-like protein (PhLP), results in the malformation of the outer segment, a cellular compartment responsible for light detection, and triggers rapid retinal degeneration. Investigation of the underlying causes by quantitative proteomics identified distinct protein networks, encompassing ∼200 proteins, which were significantly affected by the chaperonin deficiency. Notably among those were several essential proteins crucially engaged in structural support and visual signaling of the outer segment such as peripherin 2, Rom1, rhodopsin, transducin, and PDE6. These data for the first time demonstrate that normal CCT function is ultimately required for the morphogenesis and survival of sensory neurons of the retina, and suggest the chaperonin CCT deficiency as a potential, yet unexplored, cause of neurodegenerative diseases.

Normal cellular function is hinged upon the ability of the endogenous machinery to properly process newly synthesized proteins, and this is often required for enabling their functional activity. Eukaryotic cells contain several protein-folding, or chaperone, systems assisting in this process. Despite the apparent redundancy, it is believed that each chaperone system plays an important and unique role in facilitating protein folding by acting on distinct sets of substrates at unique cellular locations and/or under certain conditions (1, 2). One such chaperone system, unique to eukaryotic cells, is the Chaperonin Containing TCP-1 (CCT),1 also known as TCP-1 Ring Complex (TRiC) (for reviews see 3, 1). CCT is composed of eight different subunits that assemble into a double ring structure, creating an internal cavity that serves as a folding chamber. A pioneering study demonstrated refolding of phytochrome, a light-sensing protein of plants, by a cytosolic molecular chaperone related to CCT (4). Studies in yeast and model mammalian cell lines indicate that the action of the CCT chaperonin is critical for cellular function. It is estimated that CCT may assist folding and assembly of up to 10% of all cellular proteins (5). Several recent studies reported identification of CCT substrates by proteomic and genetic methods (6, 7). Despite the important advances, these identified substrates are rather limited in number, and the set of the proteins requiring CCT assistance is likely to vary substantially across different specialized cells. Furthermore, virtually nothing is known about the involvement of the CCT chaperonin system in the regulation of specific cellular processes in the in vivo setting of complex multicellular organisms.

Recent studies have established that the CCT function is regulated by phosducin-like proteins (PhLP) that are increasingly viewed as CCT co-chaperones (8). The best studied member of this family, PhLP, has been shown to be indispensable for the folding of the β subunits of heterotrimeric G proteins that share a common WD40 motif with many CCT substrates (see ref. in 9). PhLP forms stable stoichiometric complexes with CCT (10). In addition, it utilizes the N-terminal domain for binding to Gβ subunits. Deletion of this N-terminal domain does not affect the association of PhLP with CCT but prevents Gβ subunit folding, making a truncated PhLP, lacking the N terminus, a powerful dominant negative mutant that disrupts CCT function (9, 11). However, beyond its involvement in Gβ folding, the role of PhLP in folding other substrates and in contributing to CCT function in vivo is unknown.

To fill the gaps in our understanding of the PhLP-CCT function, we have selectively inhibited the CCT activity in rod photoreceptors of mice using transgenic expression of a dominant-negative mutant of PhLP. We have found that disrupting CCT-PhLP function affects normal photoreceptor morphogenesis, leading to their death and causing retinal degeneration. Profiling changes in protein expression by proteomics prior to the onset of the degenerative changes have identified distinct sets of affected protein networks and specific proteins that rely on the intact CCT-PhLP activity for their expression. These findings represent the first demonstration of the CCT function in the in vivo setting of mammalian differentiated cells, and also describe the range of potential CCT substrates in neurons, while presenting the first comprehensive description of changes in the proteome in the advent of retinal degeneration.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Δ1–83PhLP Transgenic Mice

All experiments involving animals were performed according to the procedures approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of West Virginia University and University of Minnesota. To prepare the dominant negative form of phosducin-like protein (Δ1–83 PhLP) containing C-terminal FLAG tag, total RNA was first isolated from the retina of a 129/SV mouse using the Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and the RNA was reverse transcribed using the mouse PhLP gene-specific RT primer 5′-ACT AAA TGA GAC TAC AA with the AccuScript High Fidelity 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Stratagene; #200820). A PCR, using the PfuUltra Hotstart PCR Master Mix (Stratagene; #600630), was used to amplify the coding sequence of PhLP from the subsequent cDNA, beginning with the 84th codon, thereby creating Δ1–83PhLP. At the same time, a SalI site and a Kozak sequence (GCCACCATGG) were added to the 5′ end, and a FLAG sequence, followed by a BamHI site and two new stop codons, were added to the 3′ end of Δ1–83PhLP. Because the 84th codon of PhLP happens to be ATG, no additional start codon was needed. The following primers were used during PCR to achieve these changes: forward primer 5′-GAG AGT CGA CGC CAC CAT GGA GCG GCT GAT CAA AAA G and reverse primers 5′- CTT GTC ATC GTC GTC CTT GTA ATC ATC TAT TTC CAG ATC GCT GTC TTC and 5′- GCC TGG ATC CCT ACT ACT TGT CAT CGT CGT CCT TGT AAT C. Two separate PCR reactions were performed to keep the primers from getting too large. Both reactions were done using the same forward primer, whereas the first reaction was done with the first reverse primer shown and the second reaction with the second reverse primer shown. After each reaction, PCR products were run on an agarose gel, and the appropriate product band cut out and purified with the Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega, Madison, WI; A9281).

The final PCR product was cloned into the pBAM4.2 vector containing a 4.4 kb mouse rhodopsin promoter and a mouse protamine I polyadenylation sequence (12). Briefly, both the final PCR product and the pBAM4.2 vector were digested with SalI and BamHI restriction endonucleases, gel purified, and ligated so the Kozak-Δ1–83 PhLP-FLAG sequence would be inserted following the mouse rhodopsin promoter and before the mouse protamine I poly(A) sequence, creating pRhop4.4k-Δ1–83 PhLP. The integrity of the construct was confirmed by sequence analysis, and the final transgene (4.4 kb rhodopsin promoter-Kozak-Δ1–83PhLP-FLAG-MPI poly(A)) was removed from pRhop4.4k-Δ1–83PhLP by digestion with restriction endonucleases KpnI and SpeI, gel purified, and used for mouse pronuclear injections at the WVU Transgenic Animal Core Facility. Founder mice carrying Δ1–83PhLP-FLAG were selected by PCR genotyping of tail genomic DNA using the following primers: forward primer 5′-GTG AAT TGA TTG GCA ATT TTG TTC G.and reverse primer 5′- ACT ACT TGT CAT CGT CGT CC. Protein expression of Δ1–83PhLP-FLAG in the retinas was confirmed and quantified by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG antibody. Colonies were established and maintained by crossing Δ1–83PhLP-FLAG mice with 129/SV mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA).

Analysis of Retinal Morphology

For the light microscopy, whole eyes were fixed in formalin for at least 48 h, dehydrated through a xylene and alcohol gradient, and paraffin-embedded. Eye cross-sections with a thickness of 5 μm were obtained, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and viewed using an Olympus AZ70 microscope. For electron microscopy, whole eyes were cleaned of extraneous tissue, and fixed overnight in Karnovsky's fixative containing 2% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% glutaraldehyde, and 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA; 15720). Whole eyes were rinsed with 0.1 m phosphate buffer, and postfixed in 2% osmium tetroxide in distilled water for 1.5 h. They were then gradually dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (25%–100%), transitioned in propylene oxide, and embedded in tEpon (Tousimis). Sections were cut at 1 micron on a Leica UCT, examined, and the area for ultrastructural analysis was chosen. Thin sections were cut at 70 nanometers on the same ultramicrotome. Photoreceptor images were acquired using a Philips CM-10 electron microscope equipped with an SIA digital camera.

Electroretinography

Mice were dark-adapted overnight, and anesthetized with a 2% isoflurane/50% oxygen mixture. Each animal's pupils were dilated with one drop per eye of a mixture of 1.25% phenylephrine hydrochloride and 0.5% tropicamide ophthalmic solution for 20 min. A disposable reference needle electrode (LKC Technologies) was inserted under the loose skin between the ears, and then custom-made silver wire electrodes were positioned on the corneas. Ganzfeld flash electroretinography recordings were carried out in a UTAS-E4000 Visual Electrodiagnostic Test System with EMWIN 8.1.1 software (LKC Technologies) according to the manufacturer's protocols.

Immunoprecipitation

Ten retinas were homogenized by short ultrasonic pulses in 0.5 ml of buffer containing 10 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, and 20% glycerol. Cell membranes and insoluble parts were cleared by centrifugation, and supernatant was incubated with 20 μl of anti-FLAG M2-Agarose (Sigma; A2220), for 1 h at room temperature. Beads were washed 4 times for 3 min with 1.0 ml of buffer. To elute bound proteins, beads were incubated with 0.1 ml of 0.25 mg/ml 3× FLAG peptide (Sigma; F4799) in 1 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, for 30 min, and the supernatant was collected and concentrated using a vacuum-dryer.

Two-dimensional DIGE Expression Profiling

The two-dimensional DIGE experiments were conducted by Applied Biomics, Inc (Hayward, CA) (www.appliedbiomics.com). Four retinas were homogenized in 0.2 ml of 30 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, and 4% CHAPS by short ultrasound pulses on ice, and then the homogenate was incubated at room temperature for 30 min on a shaker. Retinal extracts were cleared by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 30 min, and the total protein concentration in the extracts was determined using a Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad). For the analytical two-dimensional DIGE, 10 μl of extract containing 30 μg of total protein was mixed with 1 μl of a CyDye (Cy2, Cy3, and Cy5 from GE Healthcare), diluted 1:5 in dimethylformamide from a 1 nmol/ml stock, and incubated for 30 min in the dark on ice. The labeling reaction was stopped by adding 1 μl of 10 mm l-lysine, followed by a 15 min incubation under the same conditions. Equal volumes of the transgenic and control retinal extracts, labeled with different dyes, were then mixed and added to a solution containing 7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, 4% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid, 20 mg/ml dithiotreitol, DeStreak reagent (GE Healthcare), 1% pharmalytes pH 3–10 (Sigma-Aldrich), and a trace amount of bromphenol blue, all in a final volume of 250 μl. The first-dimension isoelectrofocusing was carried out in ReadyStrip IPG Strips, 13 cm, pH 3–10 (Bio-Rad), on a Multiphor II system (GE Helathcare) at 1 h using a 0–1500 V linear gradient, followed by 12 h at 1500 V and 10 °C. After the run, the IPG strips were equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6 m urea, 30% glycerol, 2% SDS, 10 mg/ml dithiotreitol, and a trace amount of bromphenol blue for 30 min. Then, the second-dimension separation was performed using 13.5% SDS-PAGE.

Each gel was scanned on a Typhoon TRIO (Amersham Biosciences), and the in-gel and cross-gel analyses of the images were performed using Image Quant 6.0 and DeCyder 6.0 software (GE Healthcare) to obtain the fold changes of the differentially expressed proteins. To identify differentially expressed proteins, a total of 1000 μg of the unlabeled proteins were separated in a preparative two-dimensional DIGE, and stained with Deep Purple total protein stain (GE Healthcare). Protein spots were picked up by an Ettan Spot Picker (GE Healthcare) based on the in-gel analysis and spot picking design by DeCyder software. Proteins were digested in-gel with Trypsin Gold (Promega, Madison, WI). The digested tryptic peptides were desalted by Zip-tip C18 (Millipore, Bellerica, MA). Peptides were eluted from the Zip-tip with 0.5 μl of matrix solution (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (5 mg/ml in 50% acetonitrile, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate), and spotted on the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) plate (model ABI 01–192-6-AB). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) MS and TOF/TOF tandem MS/MS were performed on an ABI 4700 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA). MALDI-TOF mass spectra were acquired in reflectron positive ion mode, averaging 4000 laser shots per spectrum. TOF/TOF tandem MS fragmentation spectra were acquired for each sample, averaging 4000 laser shots per fragmentation spectrum on each of the five most abundant ions present in each sample, excluding trypsin autolytic peptides and other known background ions.

Both the resulting peptide mass and the associated fragmentation spectra were submitted to a GPS Explorer work station equipped with a MASCOT search engine (Matrix Science, Boston, MA) to search the database of National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant (NCBInr) using latest software version available at the time of the analysis (October 2009) and a Mus musculus species filter. Searches were performed without constraining protein molecular weight or isoelectric point, and with variable carbamidomethylation of cysteine and oxidation of methionine residues, and with one missed cleavage also allowed in the search parameters. The C.I. % formula, which uses normal probability distribution mathematics to statistically calculate how closely the acquired data matches previous database searches under different conditions, was applied. The C.I. % calculation rates the confidence level of the score. If the score returned from the search is equal to the MASCOT significance level for the search, the score is given a 95% confidence interval. Scores that are higher or lower than the MASCOT Significance Level for the search are given higher or lower confidence intervals, respectively. Candidates with either protein score C.I. % or Ion C.I. % greater than 95 were considered significant.

iTRAQ® Protein Expression Profiling

Four retinas were homogenized in 0.15 ml of PBS buffer by short ultrasonic pulses. The resulting extract was mixed with 1.2 ml of acetone and 0.15 ml of 100% trichloroacetic acid, and incubated at −20 °C overnight. Precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation for 15 min at 38,500 × g at 4 °C, washed twice with 1.0 ml of ice-cold acetone, and vacuum-dried. Proteins were dissolved in 0.5 m triethylammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.5) containing 0.1% SDS, reduced with 5 mm tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine for 1 h at 60 °C and alkylated with 10 mm methyl methanethiosulfonate for 10 min at room temperature. Proteins were digested with 20 μg of modified porcine trypsin (Promega) at 37 °C for 16 h. iTRAQ® labeling reagents (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA) were reconstituted in ethanol, added to tryptic digests (transgene-negative retinas: iTRAQ® 114, iTRAQ® 115; transgene-positive retinas: iTRAQ® 116, iTRAQ® 117) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Differentially labeled peptide mixtures were combined and vacuum-dried. Labeled peptide mixtures were reconstituted in 0.2% formic acid (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and applied to an MCX cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA) pre-equilibrated with methanol/water (1:1, v/v). The cartridge was washed with 0.1% formic acid in 5% methanol, followed by a 100% methanol wash. Peptides were eluted from the MCX resin in 1 ml of 1.5% NH4OH in methanol, vacuum-dried and subjected to separation by liquid chromatography and MALDI mass spectrometry as follows.

Samples were separated by cap liquid chromatography (LC) using in-house packed C18 columns using 100 μm Integrafrit™ tubings (New Objective, Woburn, MA) packed with Magic C18AQ (Michrom BioResources, Auburn, CA), 5 μm 200 Å, to a length of ∼12 cm. A Tempo™ LC MALDI spotting system (ABI) was used to separate iTRAQ®-labeled peptides from each of the SCX fractions and to robotically spot LC eluates onto the LC MALDI targets in a 1232-spot format. Sample separation and acquisition of mass spec data was performed as previously described (13).

Tandem mass spectra were searched using ProteinPilot™ 2.0.1 software, revision number 67476 (AB Sciex) with the Paragon™ search algorithm against the National Center for Biotechnology Information's Reference Sequence mouse subset protein database (ver. 10–24-08, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), which contained 35,180 proteins including common contaminant proteins listed at: http://www.thegpm.org/crap/index.html. The target plus decoy (reversed) protein database contained 70,360 proteins. Search parameters were “iTRAQ® 4plex (peptide labeled)” sample type, MMTS-cysteine modifications, trypsin digest, thorough search effort with biological modifications ID focus, and 66% protein confidence threshold. The PSPEP analysis (beta version) for independent false discovery rate analysis of Paragon™ results was invoked (14).

Protein summary data that included, but was not limited to, ProteinPilot scores for protein identification, percent coverage, iTRAQ® ratios and their p values for quantitative analysis (hypotheses testing) were exported from ProteinPilot as tab-delimited text with auto bias correction applied. Proteins were included into the final report based on meeting all of the following criteria: (i) a statistically significant change in the levels between wild-type and transgenic samples (p value 116/114 or 117/114 or 116/115 or 117/115 < 0.05, error factor (EF) < 2) with (ii) consistent direction of change (up or down) between replicates, and (iii) less than 5% local protein level false discovery rate. The error factor is a statistic for reporting errors in ratios; the EF reported in ProteinPilot™ output is used for calculation of the 95% confidence interval for protein average iTRAQ® ratio. Single peptide identifications were not reported unless they could be incorporated into a pathway using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (See functional analysis of MS data below). The supplemental data containing protein and peptide summaries from all of the experiments, .group files (ProteinPilot output) and false discovery rate reports may be downloaded from ProteomeCommons.org Tranche using the following hash:

W4lIwJYSUNA55c//p + AtpPjWaIItOkW2OwghbQwpaRi1 EKYGIvRGQSIpZR0q7 × 6dHz1mroxGwpjcDjWaIItOkW2OwghbQ wpaRi1EKYGIvRGQ86/744Et1GrTPQAAAAAAAAbFQ = =

Nonquantitative Proteomics (Capillary LC-Mass Spectrometry)

Elution buffer of anti-FLAG agarose pull-down samples was exchanged to 0.5 m triethylammonium bicarbonate (pH 8.5) containing 0.1% SDS using Zeba desalt spin columns (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were reduced, alkylated, digested with trypsin in solution, and cleaned with an MCX cartridge as in iTRAQ® sample prep (see Quantitative Proteomics above). The resulting peptide mixtures were desalted using StageTips as previously described (15). Briefly, p200 pipette tips containing 2 × 16-gauge needle punches of Empore SDB-XC discs (3 m, St. Paul, MN) were equilibrated by sequentially passing through 60 μl of 80/20/0.1 acetonitrile/H2O/trifluoroacetic acid and 60 μl 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid by centrifugation. Samples were then loaded onto the column, washed with 2 volumes of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid, eluted with 80% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and dried by vacuum centrifugation.

Dried peptides were dissolved in 98:2:0.1 H2O:ACN:formic acid and were loaded at 1000 nL/min onto a reverse phase capillary column using an Eksigent 1DLC nano high pressure liquid chromatography and MicroAS autosampler. The column was packed in-house into fused silica tubing with a pulled-tip using Magic C18AQ- 5-μm, 200 Angstrom pore size resin (Michrom Bioresources, Auburn, CA) to dimensions of 14 cm × 100 μm. The elution gradient was 2%–40% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid over 60 min with a constant flow of 250 nl/min. The column was mounted in a nanospray source and eluting ions were detected using an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The spray voltage was set to 1.95 kV, the heated capillary was set at 160 °C, and the tube lens voltage was set to 145 V. Full scans were performed with the orbital trap over a range of m/z 360–1800 with at 60,000 resolution using a target value of 1E6 ions or 500 ms. The lock mass option was enabled for real-time calibration and high mass accuracy using the polysiloxane peaks of m/z 371.1012, 445.1200, and 519.1388. Unassigned charge states and singly charged species were rejected for tandem mass spectrometry. Dynamic exclusion was set for 20 s using the maximum of 500 entries and a mass window of −0.6 to 1.2 amu. Tandem mass spectra were obtained using the linear ion trap using collision-induced dissociation with a normalized collision energy of 35%, an isolation width of 2.0 m/z, and target values of 10,000 ions or 100 ms.

MS data was searched by SEQUEST v. 27 rev. 12. Monoisotopic precursor and fragment ion tolerances were set to 1 amu and 0.8 amu, respectively, and trypsin digestion was set to “partial.” Oxidation of Met was included as a variable modification, and methylthio was included as a fixed modification on Cys. Peptide probabilities were calculated using PeptideProphet (16), and the identification output was organized using Scaffold (Proteome Software, Inc. Portland, OR). Peptide identifications were filtered using “full” tryptic digest specificity, 10 ppm precursor mass tolerance, and 5% peptide probability. The data were searched against the combined forward and reversed NCBI Ref Seq mouse protein database v20081024 v3.50, including common contaminants, all of which contained 70471 entries.

Functional Analysis of MS Data

Core pathway analysis was performed through the use of Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). A dataset containing accession numbers of unique proteins identified by mass spectrometry and corresponding expression fold change (linear) was uploaded. Ingenuity Knowledge Base (Genes Only) was used as a reference set. Other analysis settings were: relationships to include (direct and indirect), include endogenous chemicals (yes), molecules per network (35) and networks per analysis (25), species (all), tissues and cell lines (all). Biological functions assigned by the software were manually examined, and molecules were regrouped into more general categories. Molecules from each of the categories were added to custom pathways, and connected using a pathway building tool with default settings. Molecules that remained unconnected were trimmed.

Quantitative Western Blot Analysis

Both retinas were homogenized in 0.2 ml of buffer containing 125 mm Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, and 6 m urea by short ultrasonic pulses delivered from a Microson ultrasonic cell disruptor equipped with a 3-mm probe (Misonix, Farmingdale, NY), resulting in complete disintegration of the tissue. The extract was cleared by centrifugation, and the total protein concentration in the extracts was determined using a NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer. Then, the protein concentration of all the compared samples was adjusted to the same value, and bromphenol blue tracking dye and 5% β-mercaptoethanol were added. For the comparison of protein levels, 10 μl of the retinal extracts from three littermates of each type, containing 25 μg of total protein, were analyzed on the same gel, so that the extracts of transgene-positive and transgene-negative littermates were randomly alternated. Proteins were separated on a 26-well 10%–20% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad), transferred to an Immobilon-FL PVDF membrane (Millipore) in Towbin buffer containing 25 mm Tris, 192 mm Glycine, and 10% (v/v) methanol for 1.5 h at 0.25 A. Quantification of the specific bands was performed on an Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) according to the manufacturer's protocols, and using primary antibodies listed in supplemental Table 5.

RESULTS

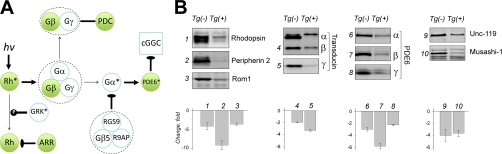

Transgenic Expression of Δ1–83PhLP in Mouse Rod Photoreceptors

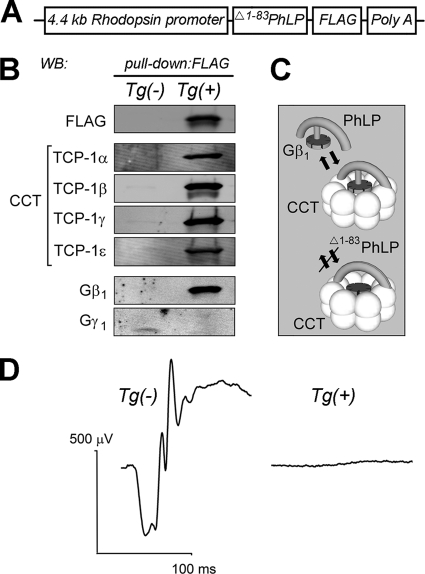

We generated transgenic mice expressing N-terminally truncated and C-terminally FLAG-tagged mouse phosducin-like protein (Δ1–83 PhLP) under the control of a 4.4 kb rhodopsin promoter to drive its expression in retinal photoreceptors (Fig. 1A). Mice carrying one allele of Δ1–83PhLP, henceforth designated as transgene-positive Tg(+) mice, were healthy and viable. Significant amounts of Δ1–83PhLP protein were present in their retinas already at postnatal day 10 (Fig. 1B). Using these mice, we first identified protein-partners of Δ1–83PhLP using a co-immunoprecipitation assay. For that, we pulled down epitope-tagged Δ1–83PhLP in the retinal extracts with anti-FLAG agarose, and identified proteins coprecipitated with Δ1–83PhLP following capillary LC-mass spectrometry followed by database searching. In the precipitates, we were able to identify with high confidence seven of the eight subunits of the chaperonin CCT complex (see supplemental Table 1), indicating that the entire CCT complex coprecipitated together with Δ1–83PhLP. Interactions with TCP-1 α, β, γ and ε were also verified by Western blotting, indicating that this binding was specific (Fig. 1B). These data are in good agreement with previous reports demonstrating that the full-length PhLP forms a complex with chaperonin CCT, and that the Δ1–83 deletion of PhLP has no significant effect on this interaction (10, 17). Substantial amounts of the Gβ1 subunit of rod transducin were also detected in the pull-downs (Fig. 1B). This Gβ1 was apparently bound to the CCT complex, rather than to Δ1–83PhLP, because the Δ1–83 deletion eliminates the conserved N-terminal α-helix of PhLP required for Gβ binding (18). Indeed, the first step in the post-translational processing of all newly translated Gβ polypeptides is thought to occur inside the folding chamber of the chaperonin CCT and prior to their permanent association with the γ subunit (9, 19, 20). Consistently, no concomitant Gγ1 was detected in the pull downs (Fig. 1B). Given previous findings in cultured cells (11), our findings in photoreceptors thus appear to corroborate a model in which Δ1–83PhLP stabilizes a complex consisting of CCT preloaded with a nascent G-protein β subunit (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Transgenic Δ1–83PhLP in the rod photoreceptor forms a tertiary complex with the chaperonin CCT and the Gβ1 subunit resulting in loss of visual function. A, Transgene utilized for the expression of FLAG-tagged Δ1–83PhLP in mouse photoreceptors. B, Western blot analyses of FLAG-agarose pull-down products in the retinal extracts of transgene-negative Tg(-) and transgene-positive Tg(+) mice at P10, detected with antibodies against FLAG, TCP-1α, TCP-1β, TCP-1γ, TCP-1ε, Gβ1, and Gγ1, as indicated. C, Model of PhLP-dependent delivery and release of Gβ1 from the chaperonin CCT that shows formation of a stable complex between Δ1–83PhLP, CCT, and Gβ1. D, Typical electroretinography responses at P25, evoked by a −10 dB UTAS-E4000 flash (0.25 candela per second per square meter). Traces were obtained using a 300 Hz high-cut filter and represent the averaging of 5 responses.

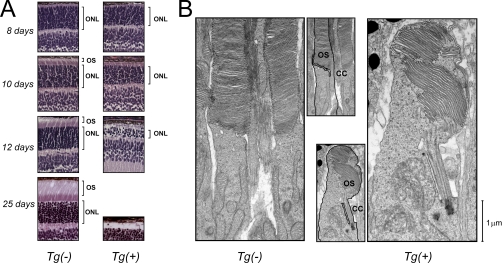

We have begun investigating the consequences of Δ1–83PhLP expression by examining the light-evoked retinal responses by electroretinography. Following weaning, nontransgenic mice exhibited normal electroretinography responses, whereas their Tg(+) littermates failed to respond to light stimulation of any intensity, which is consistent with a complete loss of photoreceptor cells (Fig. 1D). Photoreceptor death was further confirmed by an analysis of retinal morphology at different time points in postnatal development using light and electron microscopy. As evident from the progressive disappearance of photoreceptor nuclei in the retinas of Tg(+) mice, these cells were no longer viable, and died before weaning (Fig. 2A). At an earlier age, these photoreceptors also showed obvious defects in their outer segments, or the ciliary compartments uniquely responsible for light detection. In contrast to the normal outer segments developing as connecting cilium appendages, the outer segments of Tg(+) mice never separated from the photoreceptor cell body (Fig. 2B). The outer segment discs, consisting of lamellar membranes that harbor phototransduction proteins, were reduced in number and disarrayed, whereas their connecting cilia were ostensibly normal. Our data demonstrate that the targeted expression of Δ1–83PhLP in rod photoreceptors upset the outer segment membrane morphogenesis and potentially other essential photoreceptor functions.

Fig. 2.

The effect of Δ1–83PhLP expression on photoreceptor structure and viability. A, Light microscopy images illustrating the outer retina anatomy in transgene-negative Tg(-) and transgene-positive Tg(+) mice of the indicated postnatal ages. B, Ultrastructure of the photoreceptor outer segment at P10. Inserts show photoreceptor plasma membrane outlined with black. Abbreviations: ONL, outer nuclear layers; OS, photoreceptor outer segments; CC, connecting cilium.

Quantification of Changes in the Retina Proteome Induced by the CCT Deficiency

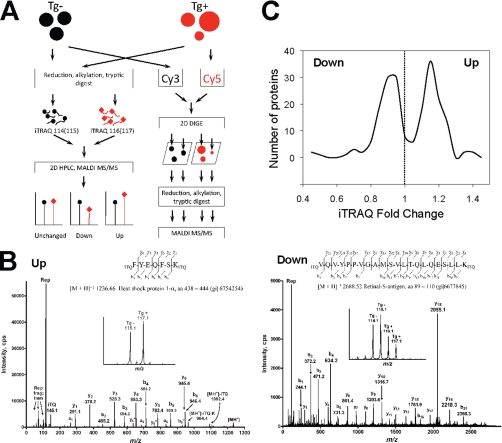

Our Δ1–83PhLP transgenic model provided a unique opportunity to investigate changes in the retina proteome induced by dysregulation of PhLP-CCT function. Such an analysis would not only reveal potential substrates for PhLP-CCT assisted folding in rod photoreceptors, but also describe changes in protein expression preceding retinal degeneration. We have used a combination of two-dimensional DIGE, which is a gel-based method for relative quantitation and iTRAQ® technology, as a relative quantitative mass-spectrometric approach, to identify proteins differentially expressed in the retinas of Tg(+) and Tg(-) littermates (Fig. 3A). For these experiments, mice of postnatal day 8 to 10 were used, as their retinal photoreceptor layer had not been profoundly altered by degenerative changes yet (see Fig. 2A).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative proteomics of the CCT-deficiency in retina. A, Approach for the quantitative analysis of the changes in the retina proteome induced in the Δ1–83PhLP transgenic model. Total protein was extracted in parallel from the retinas of wild-type (Tg-) and Δ1–83PhLP transgenic (Tg+) mice, and samples were reduced, alkylated and digested with trypsin. Peptides were differentially labeled with iTRAQ® reagents as indicated, i.e. iTRAQ®114 and 115 (●) were used for Tg(-), iTRAQ®116 and 117 (♦) for Tg(+) samples. Samples were combined, resolved by two-dimensional high pressure liquid chromatography, continuously spotted on a MALDI target upon mixing with matrix solution, and analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry using an ABI 4800 MALDI TOF/TOF analyzer. The change in protein abundance results in a similar change in iTRAQ® reporter ion intensities, allowing for the relative quantification of protein expression. Alternatively, total protein extracts from Tg(-) and Tg(+) retinas were differentially labeled with CyDyes as shown, combined and resolved by a two-dimensional difference gel electrophoresis (two-dimensional DIGE). Gels were scanned and spots showing differences in the amounts of protein, as detected by in-gel and cross-gel analyses of the images, were robotically picked, reduced, alkylated and digested with trypsin. The resulting peptide mixture was analyzed by tandem mass-spectrometry using an ABI 4700 MALDI TOF/TOF analyzer. B, Representative MS/MS fragmentation spectra of peptides assigned to up- and downregulated proteins. Continuous aa series from 438 to 444 of heat shock protein 1-α (Hsp1a) and from 89 to 110 of retinal-S-antigen (Arr) sequences. Inserts: high resolution graphs of iTRAQ® reporter ion region showing increased (Hsp1a) or decreased (Arr) abundance of the corresponding peptides in Tg(+) samples. All graphs were exported as ASCII files, and peaks were labeled in the GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA). Abbreviations are: aa, amino acids; cps, counts per second; Rep, iTRAQ® reporter ions. C, Distribution analysis of significantly changed proteins. For all proteins found to be significantly and consistently changed in iTRAQ® experiments, the total number of proteins was plotted as a function of the average linear fold change with an increment of 0.05. The dashed line represents the verge between downregulated (fold change <1) and up-regulated (fold change >1) proteins.

In our three biological replicate iTRAQ® experiments, 797, 635 and 874 proteins were identified at the 5% protein-level local false discovery rate (supplemental Table 2). The efficiency of iTRAQ® labeling reaction was 95% and above for all of the experiments as identified by mass-spectrometry. A typical MS/MS spectrum used for iTRAQ® quantification is presented in Fig. 3B. Upon fragmentation of peptides, detectable differences in the intensities of reporter ions used to differentially label wild-type and transgenic samples were revealed (Fig. 3B, inserts). The total number of unique proteins showing statistically significant changes in iTRAQ® experiments was 272. Out of these proteins, changes in the levels of 94 proteins were identified in more than one experiment. Proteins that were found in multiple experiments but exhibited inconsistent change in different directions were eliminated, reducing the final number of proteins considered for the subsequent analysis to 240. The average fold change, quantified as a ratio of iTRAQ® 116(117)/iTRAQ®114(115) values, varied from 0.417 to 1.44. Compression of the iTRAQ® dynamic range likely reflects an ion suppression effect inherent to the application of iTRAQ® to complex mixtures (21). In this scenario, other peptides within the ion selector mass tolerance window (5 Da) from the precursor peptide serve as sources of reporter ions, whereas only the precursor peptide is identified because of the ion suppression of others.

Comparative analysis of the total lysates obtained from transgenic positive and transgenic negative retinas resolved on two-dimensional gels revealed 61 spots showing different protein levels out of 2252 protein spots determined by staining with Deep Purple total protein stain (supplemental Fig. 1). Fifty unique proteins were identified in these spots by tandem mass-spectrometry. Of these, 30 were found down-regulated upon expression of Δ1–83PhLP.

The results of three iTRAQ® experiments and one two-dimensional DIGE experiment were combined, and analyzed together. Several proteins (32 in iTRAQ® experiments and 1 in two-dimensional DIGE) showed both increased and decreased in expression in separate experiments (or spots in the case of two-dimensional DIGE), and therefore were not included in the subsequent analysis. Further eliminated were proteins that showed inconsistent changes between iTRAQ® and two-dimensional DIGE experiments and proteins with p values, the statistical metric from the iTRAQ hypotheses tests, >0.05. (See ProteinPilot™ Software Online Help documentation for discussion of statistical metrics and hypothesis testing.) In the combined dataset, following all exclusions, 115 proteins were found up-regulated, and 125 were down-regulated (supplemental Table 3). Please refer to supplemental Table 4 for the list of all proteins identified in the iTRAQ experiments. Plotting the number of identified proteins as a function of their average linear fold change revealed a non-normal distribution with three distinct peaks (Fig. 3C). The two largest peaks were found to be nearly symmetrical on both sides of the arbitrary “no change” threshold (fold change = 1), and contained the majority of up- and down- regulated proteins, respectively. The third peak contained a smaller number of proteins that show the strongest decrease in levels.

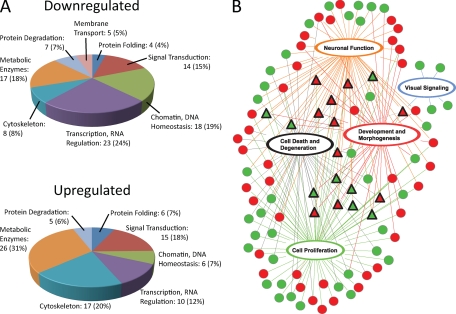

Functional Analysis of the Changes in the Retina Proteome

We have first annotated proteins showing expression level changes using the KEGG BRITE database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/brite.html) as a reference for protein classification, followed by manual assignment of proteins to categories on the basis of the information provided in their GenePept (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/) entries. Groups of proteins found to be up- and down- regulated were analyzed separately. Proteins were assigned to eight major categories reflecting key biological processes. A minimum of four members was chosen as a prerequisite for allocation to a separate category (Fig 4A, supplemental Table 3). Approximately 20% of proteins in each group could not be classified or did not have sufficient members to establish a separate category. Overall, groups of up- and down-regulated proteins were represented largely by the same categories. However, some notable differences existed. The top three categories of up-regulated proteins included metabolic enzymes (31%), cytoskeletal (20%), and signaling proteins (18%); whereas the largest down-regulated groups were proteins regulating RNA homeostasis (24%), metabolic enzymes (18%), and DNA binding proteins (19%). Notably, a category containing proteins involved in membrane transport was found only in down-regulated group.

Fig. 4.

Functional analysis of the proteome changes triggered by the CCT deficiency. A, Categorical analysis based on the molecular function of up- and down-regulated proteins performed using GenePept and KEGG BRITE databases. Category of unknown/miscellaneous proteins is not shown. B, Network analysis of the functional pathways identified by an Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Proteins were grouped and connected into pathways on the basis of physiological function. These pathways were concomitantly overlaid over all proteins, and proteins not integrated into the network were trimmed. Red shapes indicate up-regulated proteins, green, down-regulated. Triangles represent molecules incorporated in four or more pathways.

We next performed a network analysis using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis to generate insight into the most affected physiological functions (Fig. 4B, supplemental Fig. 2). We found that 112 proteins could be assigned to 5 functional groups. Each group was composed of multiple components that directly interact with each other, forming an extensive interaction network. Notably, individual elements in these networks were found both up- and down-regulated in approximately equal proportion. Furthermore, these individual groups can be linked in the single interconnected network. This additionally reveals several proteins shared by several groups that likely represent focal regulatory points, and thus broadly affect multiple cellular processes. Overall, these observations suggest that the PhLP-CCT deficiency in the photoreceptors induces changes not only in the expression of specific proteins, but also causes broad adaptive changes in several functional networks in the retina.

PhLP-CCT Deficiency Severely Affects the Phototransduction Pathway and the Photoreceptor Maintenance Systems

Examination of the proteins showing substantial down-regulation (Fig. 3C, Fig. 4B) revealed that many proteins in this group are represented by signal transduction molecules that mediate light reception (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, almost all of the phototransduction components are found among down-regulated proteins, and none of them show an elevation of their levels (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis confirmed a dramatic reduction in the levels of key molecules such as rhodopsin, transducin, and PDE6 (Fig. 5B). Importantly, individual genetic knockouts of any of these proteins have been previously shown to result in retinal degeneration (22–24). In addition, we have confirmed a reduction in the levels of four other proteins unrelated to phototransduction function, but all of which have been linked to retinal degeneration. They include peripherin 2 and Rom1, which are critically involved in outer segment membrane morphogenesis and maintenance (25, 26), along with synaptic protein Unc-119 (27) and RNA-binding protein musashi-1 (28). These data confirm the crucial role of the PhLP-CCT-assisted biosynthetic pathway in the folding and assembly of heterotrimeric G proteins, and additionally suggest that other components of the G protein signaling pathway may require CCT assistance for their biogenesis.

Fig. 5.

Δ1–83PhLP expression induces a massive down-regulation in critical components of the phototransduction cascade. A, Schematic of the core reactions in the phototransduction cascade. Proteins within this pathway found to be down-regulated are shown in green. Connecting line indicates direct binding, T-shaped lines indicate inhibition, thick arrows indicate activation, and thin arrows represent the direction of the chemical reaction. Phosphorylation is indicated as P. Protein complexes are outlined by dashed line. Rh, rhodopsin; ARR, arrestin; PDC, phosducin; PDE, phosphodiesterase; RGS9, regulator of G protein signaling 9; R9AP, RGS9 anchoring protein; GRK, G protein coupled receptor kinase; cGGC, cGMP gated channels. B, Validation of proteins essential for photoreceptor viability by quantitative Western blotting. Representative Western blots showing the levels of the indicated proteins in the whole retina extracts of Tg(-) and Tg(+) littermates at P10. Quantitative Western blotting was conducted as outlined in the Experimental Procedures. Bar graphs below each set of blots show the change of each protein level (1–10), expressed as a negative ratio of the specific band fluorescence in Tg(-) and Tg(+) samples. A specific band corresponding to the transducin α subunit was undetectable in the Tg(+) sample. Data were averaged using at least 3 littermates of each genotype and a Student t test unpaired, errors are S.E., p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

PhLP-CCT Function is Essential for Sensory Cilium Morphogenesis

One of the central observations of our study is that inactivation of the CCT function by a dominant negative isoform of PhLP profoundly affects normal development of the photoreceptor outer segment, a cilia-based organelle responsible for the acquisition of visual information. Ultrastructural examination revealed a unique defect apparently resulting from the failure of the cilium plasma membrane to separate from the rest of the cell into a distinct domain. This observation suggests that suppression of the CCT chaperonin activity affects proteins that mediate cilia membrane transport and morphogenesis. This conclusion is in agreement with the substantial down-regulation of several proteins involved in membrane transport that were identified in our proteomic screen of transgenic retinas. Further support of this model is provided by three additional lines of evidence. First, knockdown of cct1 and cct2 genes in zebra fish embryos also results in a cilia trafficking defect (29). Secondly, cilia defects that are observed in the human genetic disorder, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, which affects outer segment morphogenesis, have been recently linked to CCT dysfunction (29–31). Finally, mouse knockout studies reveal that ablation of two membrane proteins highly abundant in photoreceptor outer segments, peripherin 2 and rhodopsin, lead to outer segment formation defects that show overall similarity to the phenotype caused by the CCT disruption described in our study (22, 32, 33). Because we found both peripherin 2 and rhodopsin among the most profoundly down-regulated proteins in Δ1–83PhLP transgenic retinas, it seems plausible to speculate that the outer segment defects in our transgenic mice may potentially arise from a lack of adequate levels of these proteins, which are critically important for outer segment membrane transport and fusion (34–37). The reciprocal scenario that the outer segment collapse is the primary cause of the peripherin 2 and rhodopsin down-regulation also cannot be formally ruled out.

In conclusion, our report establishes a connection between PhLP-CCT function, cilia morphogenesis, and neurodegenerative processes, making it important to consider CCT and its associated proteins as important, yet unexplored, culprits of cilia-related degenerative disease.

Proteome Changes During Early Onset Retinal Degeneration

Here we report a striking consequence of the functional CCT disruption in rod photoreceptors—a profound retinal degeneration. The first signs of photoreceptor cell death become evident around postnatal day 10, and progress rapidly, making our transgenic mice a model for the most severe early onset retinal degeneration. Taking advantage of this unique model for retinal degeneration, we have performed the first comprehensive analysis of the changes in the entire retina proteome induced by looming photoreceptor death. We have focused our attention on the period between postnatal day 8 and 10, when the development of the photoreceptor layer of retina is fully completed, yet its degeneration is minimal, thus allowing us to preferentially look at specific changes in protein expression patterns rather than at the changes associated with the general reduction in the photoreceptor population. Overall, we found not only proteins with decreased expression, but also several proteins with up-regulated expression, suggesting massive compensatory changes. Importantly, these reported changes do not affect random proteins, but rather seem to influence the function of distinct functional networks as revealed by the cluster analysis. Consistent with the nature of the deficiency, early changes appear to primarily affect processes involved in cell survival, morphogenesis, and proliferation, indicative of the global adaptation of the retinal cells. It is interesting to note extensive changes in the immunological pathways too, as they play a widely recognized role in the progression of several degenerative conditions in the retina (38). Other significant changes are also seen in the metabolic pathways and systems that mediate nucleic acid homeostasis and signal transduction.

Our proteomic analysis reveals a reduction in the expression of several proteins previously implicated in triggering photoreceptor cell death. These include PDE6 (24), rhodopsin (22, 32), transducin (39), peripherin 2 (25, 33), Rom1 (26), musashi-1 (28), and Unc-119 (27). Importantly, we were able to validate changes in the levels of all of these proteins by quantitative Western blotting. Although qualitatively, these biochemical measurements were in complete agreement with the mass-spectrometry data in terms of the direction of the effect, the extent of the actual changes measured by Western blotting was substantially more pronounced than iTRAQ estimates. We think that underestimation of the degree of the differences in the levels of proteins in proteomic experiments come from the limitations of the iTRAQ technology, which is susceptible to dynamic range compression effects when applied to complex whole proteome situations (21). Out of the proteins detrimentally affected by the PhLP-CCT dysfunction, a profound reduction was observed in the levels of the PDE6 subunits that form a key effector enzyme in the phototransduction cascade. This provides the first evidence that the biosynthesis and/or assembly of PDE6 are critically dependent on the CCT function. The fast retinal degeneration observed upon disruption of PDE6 (24) also puts destabilization of PDE6 as a prime suspect among the major culprits of photoreceptor death evoked by the CCT suppression. However, it is also possible that simultaneous destabilization of other proteins from this group, whose individual knockouts cause only slow retinal degeneration, cumulatively results in a much faster photoreceptor layer degeneration, such as the one observed upon CCT blockade in this study.

Our proteomic screen identified more than 100 proteins that were down-regulated in response to the suppression of the chaperonin function in photoreceptors. Since we have analyzed global changes in the protein levels across the whole retina, many of these proteins do not represent the direct substrates of PhLP-CCT, but rather reflect the indirect expression effects triggered by our manipulation in various cells of the retina. Nevertheless, several of our targets, including transducin α and β subunits, phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase α, and β-tubulin have been identified by others and are widely regarded as bona fide substrate proteins of this chaperonin (6, 7). Therefore, it is tempting to propose that our list of the down-regulated proteins does include some CCT substrates. In addition, it is also entirely possible that Δ1–83PhLP affects biosynthesis of some of the identified targets via mechanisms that are different from the CCT inhibition, and identification of such mechanisms would provide new insights into the divergent functions of the phosducin family of proteins in neurons.

In summary, the present study represents the first comprehensive account describing early stage changes upon retinal degeneration in a mouse disease model. Although we recognize that the molecular nature of the degeneration trigger may substantially contribute to the specificity of the reported changes, we believe that it is the comparison of the profiles describing the changes in various models of retinal degeneration that will be a key to the system-wide understanding of the plasticity mechanisms that govern retina remodeling in degenerative conditions.

The Role of PhLP-CCT in Heterotrimeric G Protein Biogenesis

Our study in photoreceptors confirms the central role of PhLP in folding the transducin β subunit (Gβ1) that has been proposed on the basis of experiments in transfected cells (9, 11). Incidentally, Gβ1 is one of the few proteins identified as a critical CCT substrate in all reported studies, including ours. Furthermore, we found that Δ1–83PhLP forms a stable tertiary complex with CCT loaded with nascent transducin β, and by doing so, traps this polypeptide inside the chaperonin. Because rod photoreceptors express very high levels of transducin β, its trapping β inside the folding cavity of CCT makes CCT inaccessible to other substrate proteins. This is expected to make the CCT deficiency systemic, leading to instantaneous destabilization of many essential proteins that rely on this chaperonin for folding. Consistent with this model, we find that transgenic manipulation essentially eliminates the expression of the transducin α subunit that has been identified as another substrate protein of CCT (40, 7). Interestingly, we also detect a dramatic reduction in the level of the transducin γ subunit that forms an obligatory complex with Gβ1. Because the assembly of the Gβγ complex has been shown to be catalyzed by PhLP, which is thought to release folded Gβ1 from CCT prior to its association with Gγ1, this result indicates that association with Gβ1 is required for proteolytic stabilization of the Gγ1 subunit. These findings complement observations in the Gγ1 knockout mice that show that Gγ1 expression is in turn required for Gβ1 stability (39). Moreover, in striking similarity to our observations, Gγ1 ablation also dramatically reduced the levels of the transducin α subunit that was speculated to originate from the clogging of the CCT with unfolded Gβ1, which could not be released in the absence of Gγ1 (39).

Together, these observations indicate that Gβ1 folding by the PhLP-CCT complex serves as a central event that determines the expression of the entire G protein heterotrimer, making it a master regulator of G protein biogenesis. In this regard, it is curious to consider the possibility that G protein subunit assembly could be regulated by naturally occurring splice isoforms of PhLP that produce the N-terminally truncated protein with dominant negative properties (41, 42).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Goldberg, Cote and Haeseleer for generously providing the antibodies used in our study, and Lu Leach and Andrew Hall of the University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Pathology, Histology Core Facility for their technical assistance in processing, sectioning, and staining the eyes for histology.

Footnotes

* This work was supported in part by NIH grants EY018139 (K.A.M.), DA026405 (K.A.M.), and EY019665 (M.S.), and also by McKnight Land-Grant Professorship award (K.A.M.), West Virginia University Research Funding Development Grant (M.S.), and unrestricted Research to Prevent Blindness Grant to West Virginia University Eye Institute. We gratefully acknowledge core resources provided by Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. We recognize the Center for Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics at the University of Minnesota and various supporting agencies, including the National Science Foundation for Major Research Instrumentation grants 9871237 and NSF-DBI-0215759 used to purchase the instruments described in this study. Supporting agencies are listed here: http://www.cbs.umn.edu/msp/about.shtml.

This article contains supplemental Figs 1–2 and Tables 1–5.

This article contains supplemental Figs 1–2 and Tables 1–5.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- CCT

- chaperonin containing TCP-1

- TRiC

- TCP-1 ring complex

- TCP-1

- t-complex polypeptide 1

- PhLP

- phosducin-like protein

- PDE6

- cyclic GMP phosphodiesterase 6

- MALDI

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- MALDI-TOF

- MALDI-time-of-flight

- LC

- liquid chromatography.

REFERENCES

- 1. Spiess C., Meyer A. S., Reissmann S., Frydman J. (2004) Mechanism of the eukaryotic chaperonin: protein folding in the chamber of secrets. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 598–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Clarke A. R. (2006) Cytosolic chaperonins: a question of promiscuity. Mol. Cell 24, 165–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Valpuesta J. M., Martín-Benito J., Gómez-Puertas P., Carrascosa J. L., Willison K. R. (2002) Structure and function of a protein folding machine: the eukaryotic cytosolic chaperonin CCT. FEBS Lett. 529, 11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mummert E., Grimm R., Speth V., Eckerskorn C., Schiltz E., Gatenby A. A., Schäfer E. (1993) A TCP1-related molecular chaperone from plants refolds phytochrome to its photoreversible form. Nature 363, 644–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thulasiraman V., Yang C. F., Frydman J. (1999) In vivo newly translated polypeptides are sequestered in a protected folding environment. EMBO J. 18, 85–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dekker C., Stirling P. C., McCormack E. A., Filmore H., Paul A., Brost R. L., Costanzo M., Boone C., Leroux M. R., Willison K. R. (2008) The interaction network of the chaperonin CCT. EMBO J. 27, 1827–1839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yam A. Y., Xia Y., Lin H. T., Burlingame A., Gerstein M., Frydman J. (2008) Defining the TRiC/CCT interactome links chaperonin function to stabilization of newly made proteins with complex topologies. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1255–1262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willardson B. M., Howlett A. C. (2007) Function of phosducin-like proteins in G protein signaling and chaperone-assisted protein folding. Cell Signal. 19, 2417–2427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lukov G. L., Hu T., McLaughlin J. N., Hamm H. E., Willardson B. M. (2005) Phosducin-like protein acts as a molecular chaperone for G protein betagamma dimer assembly. EMBO J. 24, 1965–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLaughlin J. N., Thulin C. D., Hart S. J., Resing K. A., Ahn N. G., Willardson B. M. (2002) Regulatory interaction of phosducin-like protein with the cytosolic chaperonin complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 7962–7967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Humrich J., Bermel C., Bunemann M., Harmark L., Frost R., Quitterer U., Lohse M. J. (2005) Phosducin-like protein regulates G-protein betagamma folding by interaction with tailless complex polypeptide-1alpha: dephosphorylation or splicing of PhLP turns the switch toward regulation of Gbetagamma folding. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 20042–20050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lem J., Applebury M. L., Falk J. D., Flannery J. G., Simon M. I. (1991) Tissue-specific and developmental regulation of rod opsin chimeric genes in transgenic mice. Neuron 6, 201–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Posokhova E., Uversky V., Martemyanov K. A. (2010) Proteomic identification of Hsc70 as a mediator of RGS9–2 degradation by in vivo interactome analysis. J. Proteome Res. 9, 1510–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tang W. H., Shilov I. V., Seymour S. L. (2008) Nonlinear fitting method for determining local false discovery rates from decoy database searches. J. Proteome Res. 7, 3661–3667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rappsilber J., Ishihama Y., Mann M. (2003) Stop and go extraction tips for matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization, nanoelectrospray, and LC/MS sample pretreatment in proteomics. Anal. Chem. 75, 663–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Keller A., Nesvizhskii A. I., Kolker E., Aebersold R. (2002) Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal. Chem. 74, 5383–5392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martin-Benito J., Bertrand S., Hu T., Ludtke P. J., McLaughlin J. N., Willardson B. M., Carrascosa J. L., Valpuesta J. M. (2004) Structure of the complex between the cytosolic chaperonin CCT and phosducin-like protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 17410–17415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gaudet R., Bohm A., Sigler P. B. (1996) Crystal structure at 2.4 angstroms resolution of the complex of transducin betagamma and its regulator, phosducin. Cell 87, 577–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kubota S., Kubota H., Nagata K. (2006) Cytosolic chaperonin protects folding intermediates of Gbeta from aggregation by recognizing hydrophobic beta-strands. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8360–8365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wells C. A., Dingus J., Hildebrandt J. D. (2006) Role of the chaperonin CCT/TRiC complex in G protein betagamma-dimer assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20221–20232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ow S. Y., Salim M., Noirel J., Evans C., Rehman I., Wright P. C. (2009) iTRAQ underestimation in simple and complex mixtures: “the good, the bad and the ugly”. J. Proteome Res. 8, 5347–5355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lem J., Krasnoperova N. V., Calvert P. D., Kosaras B., Cameron D. A., Nicolo M., Makino C. L., Sidman R. L. (1999) Morphological, physiological, and biochemical changes in rhodopsin knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 736–741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Calvert P. D., Krasnoperova N. V., Lyubarsky A. L., Isayama T., Nicolo M., Kosaras B., Wong G., Gannon K. S., Margolskee R. F., Sidman R. L., Pugh E. N., Jr., Makino C. L., Lem J. (2000) Phototransduction in transgenic mice after targeted deletion of the rod transducin alpha -subunit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 13913–13918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bowes C., Li T., Danciger M., Baxter L. C., Applebury M. L., Farber D. B. (1990) Retinal degeneration in the rd mouse is caused by a defect in the beta subunit of rod cGMP-phosphodiesterase. Nature 347, 677–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen A. I. (1983) Some cytological and initial biochemical observations on photoreceptors in retinas of rds mice. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 24, 832–843 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clarke G., Goldberg A. F., Vidgen D., Collins L., Ploder L., Schwarz L., Molday L. L., Rossant J., Szel A., Molday R. S., Birch D. G., McInnes R. R. (2000) Rom-1 is required for rod photoreceptor viability and the regulation of disk morphogenesis. Nat. Genet. 25, 67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishiba Y., Higashide T., Mori N., Kobayashi A., Kubota S., McLaren M. J., Satoh H., Wong F., Inana G. (2007) Targeted inactivation of synaptic HRG4 (UNC119) causes dysfunction in the distal photoreceptor and slow retinal degeneration, revealing a new function. Exp. Eye Res. 84, 473–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Susaki K., Kaneko J., Yamano Y., Nakamura K., Inami W., Yoshikawa T., Ozawa Y., Shibata S., Matsuzaki O., Okano H., Chiba C. (2009) Musashi-1, an RNA-binding protein, is indispensable for survival of photoreceptors. Exp. Eye Res. 88, 347–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Seo S., Baye L. M., Schulz N. P., Beck J. S., Zhang Q., Slusarski D. C., Sheffield V. C. (2010) BBS6, BBS10, and BBS12 form a complex with CCT/TRiC family chaperonins and mediate BBSome assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1488–1493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stoetzel C., Laurier V., Davis E. E., Muller J., Rix S., Badano J. L., Leitch C. C., Salem N., Chouery E., Corbani S., Jalk N., Vicaire S., Sarda P., Hamel C., Lacombe D., Holder M., Odent S., Holder S., Brooks A. S., Elcioglu N. H., Silva E. D., Rossillion B., Sigaudy S., de Ravel T. J., Lewis R. A., Leheup B., Verloes A., Amati-Bonneau P., Megarbane A., Poch O., Bonneau D., Beales P. L., Mandel J. L., Katsanis N., Dollfus H. (2006) BBS10 encodes a vertebrate-specific chaperonin-like protein and is a major BBS locus. Nat. Genet. 38, 521–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stoetzel C., Muller J., Laurier V., Davis E. E., Zaghloul N. A., Vicaire S., Jacquelin C., Plewniak F., Leitch C. C., Sarda P., Hamel C., de Ravel T. J., Lewis R. A., Friederich E., Thibault C., Danse J. M., Verloes A., Bonneau D., Katsanis N., Poch O., Mandel J. L., Dollfus H. (2007) Identification of a novel BBS gene (BBS12) highlights the major role of a vertebrate-specific branch of chaperonin-related proteins in Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80, 1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Humphries M. M., Rancourt D., Farrar G. J., Kenna P., Hazel M., Bush R. A., Sieving P. A., Sheils D. M., McNally N., Creighton P., Erven A., Boros A., Gulya K., Capecchi M. R., Humphries P. (1997) Retinopathy induced in mice by targeted disruption of the rhodopsin gene. Nat. Genet. 15, 216–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sanyal S., De Ruiter A., Hawkins R. K. (1980) Development and degeneration of retina in rds mutant mice: light microscopy. J. Comp. Neurol. 194, 193–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McNally N., Kenna P. F., Rancourt D., Ahmed T., Stitt A., Colledge W. H., Lloyd D. G., Palfi A., O'Neill B., Humphries M. M., Humphries P., Farrar G. J. (2002) Murine model of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa generated by targeted deletion at codon 307 of the rds-peripherin gene. Hum. Mol. Genet. 11, 1005–1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tam B. M., Moritz O. L., Papermaster D. S. (2004) The C terminus of peripherin/rds participates in rod outer segment targeting and alignment of disk incisures. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2027–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wrigley J. D., Ahmed T., Nevett C. L., Findlay J. B. (2000) Peripherin/rds influences membrane vesicle morphology. Implications for retinopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13191–13194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chuang J. Z., Zhao Y., Sung C. H. (2007) SARA-regulated vesicular targeting underlies formation of the light-sensing organelle in mammalian rods. Cell 130, 535–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morohoshi K., Goodwin A. M., Ohbayashi M., Ono S. J. (2009) Autoimmunity in retinal degeneration: autoimmune retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. J. Autoimmun. 33, 247–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lobanova E. S., Finkelstein S., Herrmann R., Chen Y. M., Kessler C., Michaud N. A., Trieu L. H., Strissel K. J., Burns M. E., Arshavsky V. Y. (2008) Transducin gamma-subunit sets expression levels of alpha- and beta-subunits and is crucial for rod viability. J. Neurosci. 28, 3510–3520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Farr G. W., Scharl E. C., Schumacher R. J., Sondek S., Horwich A. L. (1997) Chaperonin-mediated folding in the eukaryotic cytosol proceeds through rounds of release of native and nonnative forms. Cell 89, 927–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Craft C. M., Xu J., Slepak V. Z., Zhan-Poe X., Zhu X., Brown B., Lolley R. N. (1998) PhLPs and PhLOPs in the phosducin family of G beta gamma binding proteins. Biochemistry 37, 15758–15772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gensse M., Vitale N., Chasserot-Golaz S., Bader M. F. (2000) Regulation of exocytosis in chromaffin cells by phosducin-like protein, a protein interacting with G protein betagamma subunits. FEBS Lett. 480, 184–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]