Abstract

The observation that therapeutic agents targeting vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) associate with renal toxicity suggests that VEGF plays a role in the maintenance of the glomerular filtration barrier. Alternative mRNA splicing produces the VEGFxxxb family, which consists of antiangiogenic peptides that reduce permeability and inhibit tumor growth; the contribution of these peptides to normal glomerular function is unknown. Here, we established and characterized heterozygous and homozygous transgenic mice that overexpress VEGF165b specifically in podocytes. We confirmed excess production of glomerular VEGF165b by reverse transcriptase–PCR, immunohistochemistry, and ELISA in both heterozygous and homozygous animals. Macroscopically, the mice seemed normal up to 18 months of age, unlike the phenotype of transgenic podocyte-specific VEGF164-overexpressing mice. Animals overexpressing VEGF165b, however, had a significantly reduced normalized glomerular ultrafiltration fraction with accompanying changes in ultrastructure of the glomerular filtration barrier on the vascular side of the glomerular basement membrane. These data highlight the contrasting properties of VEGF splice variants and their impact on glomerular function and phenotype.

The glomerular filtration barrier (GFB) is a unique multilayered structure demonstrating a striking dichotomy in its ability to restrict the extravasation of molecules of various sizes, shapes, and charges. Poorly permeable to large, lipid-insoluble, or anionic molecules, the GFB is highly permeable to water and small water-soluble agents. In glomerular disease, this strict segregation is impaired or lost, resulting in albumin in the urine. The mechanisms underlying proteinuria have been widely investigated, both because of its link to glomerular disease (heavy proteinuria tends to be associated with more severe glomerular lesions) and because, even at modest levels, proteinuria is now categorized as a major risk factor for vascular disease,1 even among the general population.2,3

Glomerular permselectivity remains poorly understood; however, although the controlling mechanisms of the normal glomerular phenotype are probably highly complex, in simple terms, they are likely to depend on two general factors: (1) Physical structure (e.g., foot processes, slit diaphragms and related proteins, fenestrae, glomerular basement membrane (GBM), glycocalyx, subpodocyte space [SPS]) and (2) the function of cell types that contribute to the barrier, through either physical change (e.g., podocyte movement, contraction, effacement) or growth factor expression/secretion (e.g., VEGF-A, angiopoietin-1, VEGF-C)—that is, podocyte-derived agents that are known to influence permeability in other microvascular beds and the receptors for which reside on the glomerular endothelial cells (GECs)4 and sometimes on the podocytes themselves.5 The specific role of podocyte-derived VEGF remains contentious; however, its angiogenic/permeability potency ensures continuing interest, even in the context of a VEGF glomerular literature that is replete with apparent contradictions and, on initial inspection, unexplainable observations.

For example,

Constitutive transgenic podocyte-specific VEGF164 overexpression leads to proteinuria, collapsing nephropathy, uremia, and death 5 days after birth6; however, podocyte VEGF-A glomerular reduction (heterozygous inactivation) similarly demonstrates nephrotic syndrome, uremia, and death at 2 to 5 weeks in the context of glomerular endotheliosis.6

In mature glomeruli, induced transgenic podocyte-specific VEGF164 overexpression results in increased water permeability-area product (LpA/Vi) and protein-creatinine ratio at 7 days after induction7; however, systemic inhibition of VEGF with Avastin in humans also causes proteinuria8 and occasionally renal failure.9

Anti-VEGF antibody administration reduces proteinuria in an animal model of diabetic nephropathy10 but induces proteinuria in normal animals,11 and VEGF administration in some nondiabetic animal models ameliorates glomerular injury.12

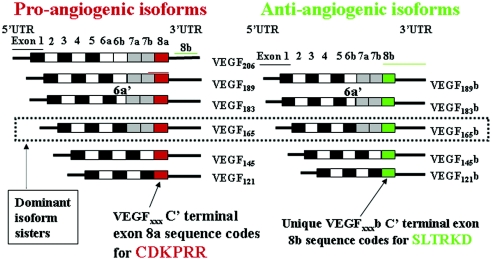

Many of these carefully conducted studies are irreconcilable if VEGF is regarded only as a proangiogenic, propermeability vasodilator acting solely on endothelial cells. Two key changes in our understanding of VEGF have forced a radical reevaluation of VEGF biology. The first is the identification of the antiangiogenic VEGFxxxb family of peptides in 2002.13 In essence, VEGF-A comprises two peptide families derived by alternative mRNA splicing of the terminal exon 8 through competing 3′ splice sites. Family members, numbered by their amino acid content, have strikingly contrasting properties.14 The distinguishing content of the families is the 18-nucleotide open reading frame encoded by the final exon, coding for six amino acids: The inclusion of exon 8a resulting in the conventional proangiogenic, propermeability family of peptides (VEGFxxx). Replacement of 8a by exon 8b in the VEGFxxxb family produces peptides that are antiangiogenic, inhibit permeability chronically, and reduce rather than promote tumor growth.13,15–20 Alternative splicing of exons 6 and 7 produces multiple isoforms within each family with differing heparin-binding properties. The dominant member in each family contains 165 amino acids (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

VEGF-A can be subdivided into two subfamilies. Nomenclature is based on amino acid size of final peptide. Two mRNA isoform families are generated. The proangiogenic isoforms (VEGFxxx, left) are generated by proximal splice site (PSS) selection in exon 8 (i.e., 8a) and the antiangiogenic (VEGFxxxb, right) family from exon 8 distal splice site choice (exon 8b; DSS). Thus VEGF165, formed by PSS selection in exon 8, has VEGF165b as its distal splice site (DSS) sister isoform—the DSS selected mRNA encoding a protein of exactly the same length as VEGF165. Exon 6a′ occurs in VEGF183 as a result of a conserved alternative splicing donor site in exon 6a and is 18 bp shorter than full-length exon 6a. VEGF206b has not yet been identified. UTR, untranslated region.

The second change in VEGF biology has been that, despite its nomenclature, VEGF is not endothelial cell specific but also has effects on nonendothelial cells. VEGF165, for example, is neuroprotective,21 and both VEGF165 and VEGF165b have human podocyte cytoprotective properties.5,20,22

In the context of established proangiogenic, propermeability properties of VEGF165 (and the murine equivalent VEGF164), the characterized phenotype of constitutive podocyte–specific VEGF164 transgenic overexpressing animals,6 and recent in vitro data suggesting that VEGF165b reduces VEGF165-induced human endothelial monolayer permeability,20 in addition to being antiangiogenic in vivo,14 here we describe the derivation of heterozygous and homozygous transgenic animals that constitutively overexpress VEGF165b in podocytes to address the hypothesis that sustained expression of exon 8b containing VEGF peptides will produce a distinct phenotype from transgenic animals overexpressing exon 8a–containing peptides.

Results

Generation of pNeph-VEGF165b Construct

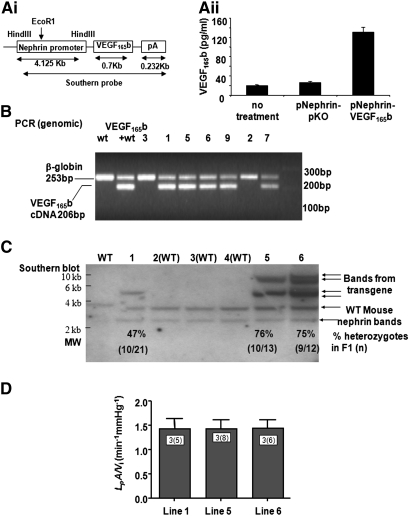

VEGF165b-cDNA was cloned into an expression vector under the control of the Nephrin promoter (Figure 2Ai). To assess transfection and construct functionality, we transfected human conditionally immortalized podocytes with the construct, and assessed VEGF165b expression in the cell supernatant at 48 hours. Significantly more VEGF165b was seen in transfected podocytes compared with control vector or untransfected cells (Figure 2Aii). Potential founder lines were identified by PCR (Figure 2B) and Southern blot analysis (Figure 2C) of pups born from injected embryos. No difference in isolated glomerular functional phenotype (LpA/Vi) was seen between potential founder lines 1, 5, and 6 (Figure 2D), but line 1 was used for subsequent heterozygous and homozygous breeding studies.

Figure 2.

Generation of pNeph-VEGF165b heterozygous transgenic mice. (A) VEGF165b is cloned into an expression vector under the control of the Nephrin promoter (Transgenic Construct; Ai). When transfected into human podocytes, VEGF165b expression was significantly greater than control vector or untransfected cells (Aii). (B) PCR screen of pups born from injected embryos. (C) Southern blot, confirming single insertion into genomic DNA. The gDNA is digested with EcoRI, and a probe made from the cDNA is used to generate the transgene. There was a single EcoRI site in the 5′ end of the insert, so multiple insertions should generate multiple different-sized bands in the transgene. There is only a single band in line 1, indicating a single insertion point (insertions into multiple sites would generate multiple bands). See Supplemental Figure S1. Each lane in B and C represents a distinct animal line. The mouse nephrin sequence is also detected as seen in the WT animals (two bands as shown by arrows). Line 1 is used for establishment of the subsequent heterozygous and homozygous breeding colonies. (D) Of note, the ultrafiltration fraction from potential founder lines is not different from each other.

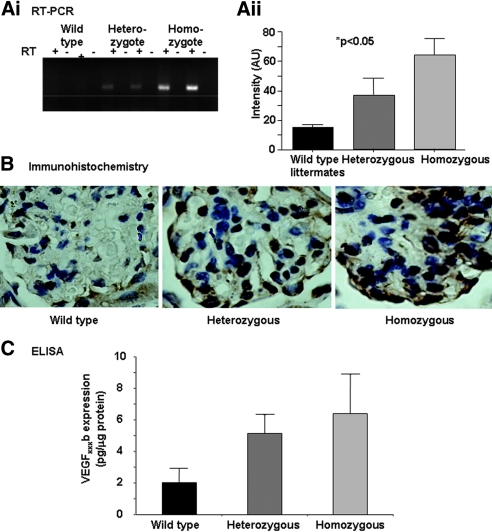

VEGF165b Expression in Renal Cortex of pNeph-VEGF165b Heterozygous and Homozygous Transgenic Mice

Exon 8b–specific reverse transcriptase–PCR for the transgene (P < 0.05, χ2 test for trend, n = 3 per group; Figure 3A), immunohistochemistry (Figure 3B) using an anti-human VEGF antibody, and an exon 8b–specific ELISA (Figure 3C) on protein extracted from renal cortex (P < 0.01, ANOVA) all demonstrated a gradient of expression from wild-type (WT) littermate controls through heterozygous to homozygous animals.

Figure 3.

pNeph-VEGF165b heterozygous and homozygous transgenic mice overexpress VEGF165b in the renal visceral glomerular epithelial cells (podocytes). (A) VEGF165b expression is determined in the renal glomerulus (exon 8b–specific reverse transcriptase–PCR of renal cortex for transgene, P < 0.05, χ2 test for trend; n = 3 per group; Ai and Aii). (B) Immunohistochemistry using anti-human VEGF (A20 Santa Cruz) ×1000 under oil, demonstrating transgenic VEGF expression in the podocytes. (C) ELISA of protein extracted from renal cortex from transgenic and WT mice using VEGFxxxb-specific ELISA (R&D Systems). P < 0.01 (ANOVA).

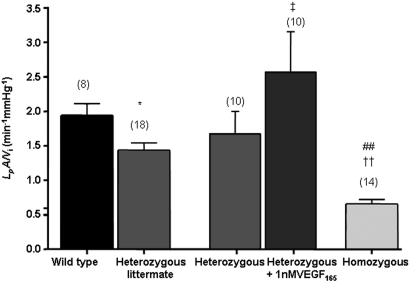

Functional Phenotype:Podocyte-Specific VEGF165b Overexpression Reduces Glomerular Water Permeability

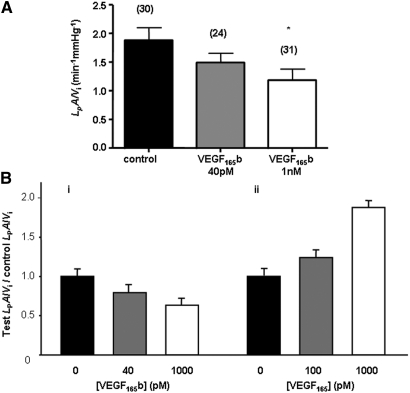

To determine whether isolated glomerular permeability to water was altered by podocyte VEGF165b overexpression, we investigated normalized glomerular Kf(LpA/Vi) using the glomerular swelling assay modified by Salmon from Savin et al.23 A marked difference was seen in LpA/Vi among the three groups (Figure 4) from 1.95 ± 0.16 nl/min per mmHg in WT to 1.43 ± 0.10 nl/min per mmHg in heterozygous to 0.67 ± 0.07 nl/min per mmHg in homozygous mice (Table 1). To determine whether this reduction was attenuated by exogenous VEGF165, we measured LpA/Vi from glomeruli from transgenic mice, then exposed the same glomeruli to 1 nM VEGF165 for 1 hour as described previously.23 Figure 4 shows that this restored LpA/Vi to levels similar to WT. LpA is a permeability-area product; therefore, glomerular capillary surface area was calculated in controls and transgenics. No significant difference was seen: WT glomeruli (mean 4.90 ± 0.76 × 104 μm2, n = 4), transgenic glomeruli (mean 4.40 ± 0.43 × 104 μm2, n = 3; P > 0.55). This suggests that changes in LpA/Vi were due to changes in water permeability alone rather than reduced capillary area as a result of developmental abnormalities. We also estimated VEGF164 expression in transgenic mice and WT mice and found no evidence of compensatory increase in VEGFxxx isoforms (data not shown). Plasma creatinine, urea levels, and GFR (306.70 ± 57.52 μl/min, n = 4 WT controls versus 344.10 ± 41.80 μl/min, n = 4 heterozygotes) were not significantly different. Urinary protein-creatinine ratio of urine collected using metabolic cages showed lower values in the homozygous animals (Table 1) but did not reach significance. Body weight of animals and blood glucose levels were also unchanged in the transgenic mice. To assess whether exogenous administration of recombinant human VEGF165b (rhVEGF165b) could reproduce the reduction in LpA/Vi, we incubated WT glomeruli with increasing dosages of rhVEGF165b. Exogenous rhVEGF165b significantly reduced Kf in a dosage-dependent manner (Figure 5A). Figure 5B summarizes the characteristically distinct permeability changes induced in LpA/Vi elicited by VEGF165 (increase) and VEGF165b (decrease).

Figure 4.

Podocyte-specific VEGF165b overexpression reduces glomerular water permeability. The normalized glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient is significantly reduced in mice with heterozygous and homozygous VEGF-A165b overexpression. The reduced glomerular water permeability in VEGF165b-overexpressing heterozygous mice is rescued by incubation with VEGF165. Paired measurements are done on the same glomerulus before and after treatment. Bars represent means ± SEM LpA/Vi measurements. Numbers in parentheses represent number of glomeruli studied. *P < 0.05 versus WT littermate; ††P < 0.001 versus WT; ##P < 0.001 versus heterozygous, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction; ‡P < 0.05, comparison of repeated LpA/Vi from identical glomeruli before and after VEGF165 treatment from the same NephVEGF165b-transgenic mice (paired t test).

Table 1.

Transgenic parameters characterized

| Parameter | WT Littermate Controls | Heterozygous Animals | Homozygous Animals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glomerular volume (μl) | 0.98 ± 0.16 (n = 8) | 0.73 ± 0.07 (n = 18) | 1.56 ± 0.11 (n = 36) |

| LpA | 1.93 ± 0.32 (n = 8) | 1.00 ± 0.12 (n = 18) | 1.06 ± 0.16 (n = 23) |

| LpA/Vi | 1.95 ± 0.17 (n = 8) | 1.44 ± 0.11 (n = 18) | 0.67 ± 0.07 (n = 23) |

| uPCR (mg/mmol) | 20.16 ± 2.55 (n = 8) | 20.74 ± 2.80 (n = 10) | 14.80 ± 2.78 (n = 3) |

| Plasma creatinine (μmol/L) | 3.40 ± 1.21 (n = 5) | 4.50 ± 1.20 (n = 6) | 6.00 ± 1.53 (n = 3) |

| Plasma urea (mmol/L) | 8.60 ± 0.10 (n = 5) | 9.32 ± 0.50 (n = 6) | 11.07 ± 0.90 (n = 3) |

| GFR (μl/min) | 306.70 ± 57.50 (n = 4) | 344.10 ± 41.80 (n = 4) | |

| Fenestration density (per μm GBM) | 3.10 ± 0.10 | 0.64 ± 0.30 | 1.28 ± 0.30 |

| % SPS coverage | 55 ± 5 | ND | 41 ± 10 |

| Foot process width (nm) | 400 ± 40 | ND | 460 ± 70 |

| GBM thickness under SPS (nm) | 248 ± 10 | ND | 252 ± 9 |

| GBM thickness uncovered | 196 ± 6 | ND | 240 ± 14a |

ND, not done; uPCR, urinary protein-creatinine ratio.

aP < 0.05.

Figure 5.

Exogenous application of VEGF165b to individual control WT glomeruli decreases the normalized glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient. (A) Populations of normal WT glomeruli are exposed for 60 minutes to control solution, 40 pM to 1 nM rhVEGF165b. Bars represent means ± SEM LpA/Vi measurements. Numbers in parentheses represent number of glomeruli studied. *P < 0.05 versus control, Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunnett correction. (B) Contrasting properties of rhVEGF165b on normalized LpA/Vi of isolated single murine glomeruli (i) and our previously published data39 of similar concentrations of rhVEGF165 on rat glomeruli (ii) using the same assay.

Ultrastructural Phenotype:Podocyte-Specific VEGF165b Overexpression Reduces Fenestral Size and Density

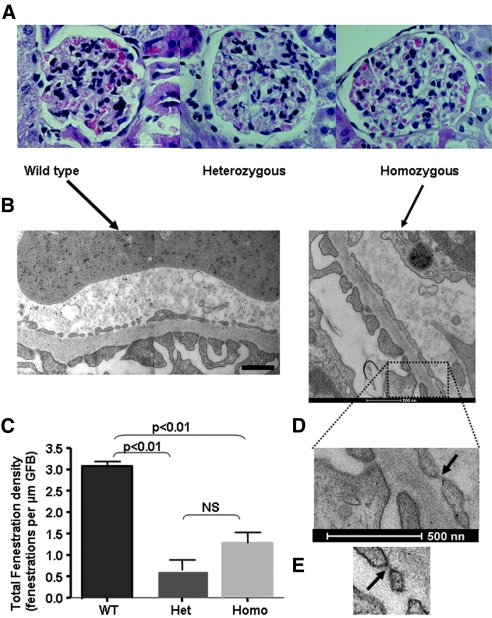

Up to 21 months, the transgenic mice had normal behavior, growth rate, and feeding and no urinary sediment. Histologic assessment with light microscopy also revealed no obvious abnormality (Figure 6A); however, serial transmission electron microscopy (EM) studies revealed that typical glomerular endothelial open fenestrations were difficult to identify in transgenic mice (Figure 6B). Ultrastructural measurements revealed no change in SPS coverage, foot process width, and GBM thickness in SPS-covered areas (Table 1); however, the GBM in areas of the GFB devoid of SPS coverage were significantly thinner in WT controls (196 ± 6 nm) versus homozygous animals (240 ± 14 nm; P < 0.01). In addition, fenestration density was reduced in transgenic animals (Figure 6C, Table 1). Moreover, as expected, the vast majority of fenestrations in WT littermate controls did not demonstrate fenestral diaphragms. In contrast, many of the fenestrations in the transgenic animals contained electron-dense material (Figure 6D) that contrasted with the conventional (but rare) distinct diaphragms (approximately 2%24) seen in normal glomerular endothelium in vivo (Figure 6E). Because, it was not possible to define whether these fenestrations contained atypical diaphragms, excess glycocalyx, glycocalyx-like material, or “sieve plugs”25,26 or was simply a reflection of smaller fenestrations with more frequent (relatively) sectioning through the attenuated edge of fenestrations, we termed these “closed” fenestrations. We therefore performed further EM characterization using 40-nm sections from paired samples fixed and processed in parallel from homozygous animals and littermate controls, and, because two filtration areas of the GFB (with and without covering SPS27–29) have been identified, our analysis differentiated between these areas. Random measurements (in excess of 200 from multiple animals) were made using a Photoshop grid (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

VEGF165b overexpression reduces the number of endothelial fenestrations. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin light microscopy is normal in all animals. (B and C) EM: No significant difference in the area of the GFB enclosed by SPS is seen (WT controls 55 ± 5% versus homozygous 41 ± 10%; NS); however, a marked reduction in fenestration number and size (C) was observed in heterozygous and homozygous animals. EM studies used 70-nm sections. (D and E) “Closed” fenestrations containing electron-dense material are prominent in homozygous animals (arrow), contrasting with more conventional, rare diaphragmed fenestrations (E, arrow). Magnification, ×100 in A.

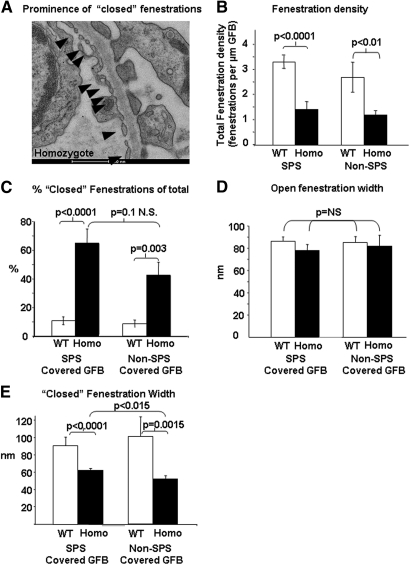

Figure 7.

VEGF165b overexpression results in “closed” endothelial fenestrations. Ultrastructural phenotype on vascular side of GBM of homozygous animals and fenestration parameters determined using 40-nm sections. (A) Example of prominence (nine of 11) of “closed” fenestrations in the glomeruli from homozygous transgenic animals. (B) Fenestration density is significantly reduced in both functional areas of the GFB. (C) Percentage of closed fenestrations as a proportion of total fenestrations. (D) Open fenestration width. (E) Closed fenestration width. Homo, homozygous for transgene; SPS covered GFB, areas of GFB through which filtrate has to exit a restrictive SPS to reach Bowman's space; non–SPS-covered GFB, areas of GFB through which filtrate enters Bowman's space directly.

On the urinary side of the GBM, the podocyte foot process slit diaphragm width and density were not significantly different (Table 1). In contrast, on the vascular side, there was a significant increase in the proportion of “closed” fenestrations (Figure 7, A and C). Reduced fenestration number was preserved in both SPS- and non–SPS-covered areas of the GFB (Figure 7B). Furthermore, although the open fenestrations were of a similar size in WT controls and homozygous animals (Figure 7D), the closed fenestrations were significantly narrower (Figure 7E).

Although a detailed study of the nature of the closed fenestrations was not possible, we attempted to clarify whether the overexpression of VEGF165b had influenced plasmalemma vesicle protein 1 (PV-1) expression. We were unsuccessful using the established antibodies for immunogold studies and therefore studied PV-1 expression by Western blotting in conditionally immortalized GECs. These studies did not show any significant change in PV-1 expression at the protein level in GECs exposed to VEGF165b.

Discussion

The traditional view of the GFB as a trilayered filter has evolved significantly30 with the identification of previously overlooked ultrastructural27–29 and biochemical (glycocalyx)31 features that contribute additional resistance to flow and with the realization that the GFB is more than a fixed series of passive sieves that resist water and solute movement in a manner predicted by simple biophysical models. Overlying complex ultrastructure are signaling pathways initiated within the GFB serving to maintain (or modify) the barrier, acting across the GFB, and involving “cross-talk” between podocytes and adjacent GECs.32 Such cross-talk includes the VEGFxxx/VEGFxxxb–VEGF-R2; VEGF-C–VEGF-R3, and Ang-1–Tie2 axes,33–36 which elicit paracrine alterations counterintuitively in the adjacent but nevertheless “upstream” glomerular endothelium. Mathematical models indicate that such molecules can diffuse upstream to elicit these effects,37 and such predictions are underpinned by the functional phenotype of transgenic models manipulating the expression of podocyte-derived molecules in vivo,6,9,38,39 the phenotypes of some of which (proteinuria and glomerular thrombotic microangiopathy)9 are primarily endothelial and sometimes reflected clinically in the context of anti-VEGF therapy (e.g., bevacizumab9). These studies provide robust evidence that podocyte-derived VEGF is required to maintain the mature GEC phenotype. Overlying such paracrine effects are autocrine properties of VEGF on the podocytes themselves. This is true for VEGF1655,22 and VEGF165b,20 which, in the context of glomerular epithelial cell survival, have similar properties.5,20

There is mounting evidence that podocyte-derived VEGF-A plays a crucial role in maintaining the filtration barrier, and although its specific role in an established glomerulus is incompletely understood, multiple roles of glomerular VEGF and multiple VEGF isoforms with widely contrasting properties14 perhaps go some way toward explaining the seeming contradictions in the literature. Eremina et al.6 were the first to support the notion that an optimal “dose of glomerular VEGF” was required to underpin the normal glomerular phenotype (for review, see reference 40). Our study suggests the “dose of VEGF” may include qualitative aspects (the balance of VEGFxxx/VEGFxxxb isoforms) as well as quantitative (the absolute amounts of bioavailable VEGF isoforms), particularly because all of the knockouts of VEGF have also been knockouts of VEGFxxxb isoforms, and all studies using inhibitors of VEGF (including bevacizumab) have inhibited both families.

The podocyte-VEGF164 overexpressing mice6 developed uremia and collapsing nephropathy, a glomerular lesion typical of HIV nephropathy.41 Mice died at day 5. This contrasts sharply with the podocyte-VEGF165b phenotype of modestly reduced permeability to water and urinary protein loss in animals with a normal life expectancy. Future experiments on crosses between these two lines to assess the effectiveness of VEGFxxxb in ameliorating the phenotype of the animals in the study by Eremina et al.6 may be informative, as would isoform-specific knockouts.

Intriguingly, the heterozygote podocyte-VEGF knockout and the anticipated sequestration of VEGF (all isoforms) by soluble VEGF-R1 (sFlt) overexpression42 demonstrate a loss of fenestrations6; in contrast, VEGF165 induces endothelial fenestrae ex vivo.43 The findings we present here suggest the qualitative balance of VEGF may be important for the establishment and maintenance of fenestrations and the phenotype thereof in vivo. We previously showed that at least some of the VEGF expression at the S-shape stage of glomerular development is VEGFxxxb.20 Of note, in rodent development at least, the earliest fenestrations have diaphragms24 that may reform in association with injury.24 The lack of an effect on PV-1 suggests that the podocyte-VEGF165b phenotype may not simply relate to changes in the expression of this endothelial glycoprotein, but, clearly, further studies including immunogold may clarify the situation.

Exon 8b–specific isoforms predominate in many human tissues44 and contribute approximately half of the VEGF in the normal human kidney.16,20 The contrasting properties of the two VEGF isoform families is striking. VEGF165b has been shown in receptor-binding studies, in in vitro endothelial proliferation and migration assays, in ex vivo isolated resistance vessel myograph studies, and in in vivo neovascular and tumor growth models to inhibit the actions of VEGF165.13,19,45,46 Thus, parenterally administered rhVEGF165b (intraperitoneal and subcutaneous) halts colonic carcinoma tumor growth in nude mice.17 We have also shown that transgenic mice overexpressing VEGF165b in mammary tissue have inhibited physiologic angiogenesis.15 VEGF165b inhibits both angiogenesis and vasodilatation through inhibition of VEGF165-mediated full activation of VEGF-R2.47 The description here of a glomerular phenotype “at odds” with that of podocyte-specific VEGF164 overexpression, in that VEGF165b overexpression in the podocytes does not result in overt glomerular pathology, adds further weight to the argument that exon 8a and exon 8b containing VEGF isoforms have opposing properties in terms of microvessel permeability in both systemic and highly specialized microvessels.

Although permeability of the isolated glomeruli was reduced in our transgenic animals, GFR was unchanged. This seems counterintuitive but may simply reflect that in the isolated glomerulus technique, it is the properties of the barrier per se that are studied, in the absence of confounding factors known to influence single-nephron GFR such as intraglomerular pressure and flow. Direct comparisons are therefore inappropriate.

In regard to microvessel permeability, studies using the Landis-Michel micro-occlusion technique, in cannulated single capillaries, demonstrated that an rhVEGF165b bolus increases microvascular permeability to water for a few seconds only (rapidly returning to normal), mediated by VEGF-R135; however, there is no physiologic correlate to this, and in the same study, no long-term change in water permeability was seen in response to VEGF165b, in contrast to that seen with VEGF165.33 VEGF165b also inhibits VEGF165-mediated reduction in transendothelial monolayer resistance (increased permeability) in vitro.20

We have demonstrated no difference in glomerular capillary surface area within transgenic compared with WT animals, suggesting VEGF165b overexpression does not adversely affect glomerular development. Indeed, VEGF165b is expressed early in human kidney embryonic development,20 although at a lower mRNA level than in the adult.48 Although an effect on glomerular development might be postulated, nephrin (and therefore transgene) expression occurs relatively late in kidney development in rodents (day 18 of 21 in rats)49—that is, at the capillary loop stage.50 In addition, it cannot be assumed that the differential permeability properties of VEGF165 and VEGF165b in vessels are maintained in the embryo. Even if this were the case, it is also unknown how their putative conflicting properties on embryonic endothelial cells may interact with the similarity of their cytoprotective effects on glomerular epithelial cells.20

The finding that exon 8a containing conventional isoforms (e.g., VEGF165) tend to predominate in de-differentiated human conditionally immortalized podocytes that lack exon 8b–containing isoforms, the latter being present in differentiated podocytes, prompted Schumacher et al.48 to suggest that podocyte maturation (GECs and hence the GBM) may depend on isoform family ratio. The study by Schumacher et al. of VEGF isoform expression in Denys-Drash syndrome (DDS; glomerular dysgenesis, male pseudohermaphroditism, FSGS, and uremia) showed that DDS podocytes produce ample proangiogenic, propermeability VEGF165 but completely lack the antiangiogenic, antipermeability form VEGF165b. The factors that influence splicing between the VEGF-A families are emerging,51 and because at least 74% of human genes demonstrate alternative mRNA splicing,52 it is perhaps no surprise that many podocyte-derived products display this property (e.g., the transcription factor WT-1, which has been implicated in Wilms' tumors and DDS53). WT-1 has four major isoforms. The zinc finger regions of WT-1 bind both DNA and RNA, and although WT-1 targets are unknown, mutations in WT-1 in humans lead to mesangial sclerosis and well-characterized glomerular lesions.53,54 It has been suggested that WT-1 might regulate factors that affect vascular development, such as VEGF.53 WT-1 may therefore influence the splicing of VEGF in podocytes and the associated glomerular phenotype. We have now shown that VEGF165b is downregulated in DDS podocytes because WT1 acts as a repressor for a splice factor kinase named SRPK1, which stimulates VEGF proximal splicing through phosphorylation and activation by nuclear localization of the splice factor ASF/SF2 (Amin et al., submitted). Altered VEGF isoform balance has been potentially linked to other forms of glomerular lesion (e.g., in a transgenic model in which the Hippel-Lindau gene was deleted39), leading to increased HIF-1α subunits, increased Cxcr4 expression, and crescentic glomerulonephritis. In this model, the podocytes were functionally responding to the signaling pathways activated in hypoxia, which are known to increase VEGFxxx expression but have no effect on VEGFxxxb production.18

In summary, here we show that VEGF165b overexpression results in physiologically healthy renal function and normal light microscopy but with reduced glomerular permeability to water associated with ultrastructural fenestral changes and contrasts with podocyte-specific VEGF164 overexpression.6 The correlation of an ultrastructural change and an associated change in physiology (permeability to water) lends credence to the view that fractional fenestral area is a significant determinant of glomerular filtration24 and that fenestral density size and phenotype may be a dynamic process that responds to single-nephron or whole-organ demands.

Concise Methods

Animal Maintenance

All transgenic lines were generated on C57BL6 × CBA/CA background. Animal care/procedures were conducted within UK Home-Office protocols/guidelines. For permeability experiments, F2 to F3 generation male transgenic mice and WT littermate controls were used.

Construction of pNephrin-VEGF165b

pcDNA3-VEGF165b was cloned as described previously,13 and a plasmid was generated with the mouse nephrin promoter upstream of VEGF165b-cDNA and a poly-A signal (Figure 2Ai). The nephrin promoter (courtesy of Prof. S Quaggin) DNA fragment was inserted with rapid DNA ligation kit (Roche Applied Science) into the linearized pcDNA3-VEGF165b, from which the cytomegalovirus promoter had been deleted and correctly oriented colonies selected.

Podocyte Transfection

Human conditionally immortalized visceral glomerular epithelial cells previously characterized55 (donated by Prof. Moin Saleem) were transfected with equal amounts of pNephrin-VEGF165b and empty vector 5′-Nephrin-pKO. Expression of VEGF165b in the supernatant of control, mock-transfected, and pNephrin-VEGF165b–transfected podocytes were analyzed by VEGFxxxb family–specific ELISA (DY304E; R&D Systems; Figure 2Aii).

Generation of Transgenic Mice

The DNA fragment of murine pNephrin-VEGF165b-pA for microinjection was generated with HindIII and HaeII digestions of pNephrin-VEGF165b and gel-purified using QIAEX II DNA Extraction kit (QIAGEN) before final purification with elutip minicolumns (Schleicher & Schuell biosciences). Microinjection of purified DNA into embryos was carried out by B&K Universal Ltd. Successfully injected embryos were cultured overnight and transplanted into oviducts of pseudopregnant mice. After weaning, tail-biopsy genomic DNA extracts were screened for the transgene via PCR (Figure 2B) and Southern blotting (Figure 2C). Animals were bred to homozygosity using a standard breeding/genotyping program. For generation of homozygous animals, siblings (from founder line 1) were crossed, and subsequent pups of the F1 generation, themselves crossed with WT mice, were also genotyped. For homozygous animals, all subsequent pups from at least three litters and a minimum of 20 pups were required to carry the transgene and all pups from subsequent litters. Numbers of animals for functional phenotype analysis were determined by the numbers required to demonstrate statistical analysis (from previous data showing that to demonstrate a significant difference in glomerular LpA/Vi of 25%, the use of a minimum of three animals and five glomeruli is required), restrictions of UK home office license, and ethical review board.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Primer pair (forward 5′-TCAGCGCAGCTACTGCCATC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGCTGGCCTTGGTGAGGTT-3′) gave a PCR product of 208 bp to detect transgene specifically. Internal control primers for mouse β-globin (band 253 bp; forward 5′-ACGTCCTAAGCCAGTGAGTG-3′ and reverse 5′-CAGCCTTCTCAGCATCAGTC-3′) was included in amplification. Each reaction contained 2 μl of 10× buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 500 nM forward and reverse primers, 0.5 U of Taqpolymerase (Abgene), 0.5 μl of gDNA, and water to 20 μl. PCR was initiated at 94°C for 4 minutes, then 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 62°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes.

Southern Blotting

Ten to 15 μg of tail gDNA was digested with EcoRI restriction enzyme. DNA was separated on 0.8% Agarose gel, denatured, and capillary-transferred to Hybond N+ membrane (Amersham). DNA was fixed with baking at 80°C for 2 hours. Membranes were probed with an alkaline phosphatase–labeled DNA fragment, exactly the same as the one used for microinjection. Probe preparation and transgene detection followed the manufacturer's guideline of Gene Images Alkphos Direct Labeling and Detection System (Amersham).

Reverse Transcriptase–PCR

Briefly, total RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen) extraction and DNase I (Invitrogen) digested per the manufacturer's instructions to prevent gDNA contamination. One microgram of DNase-treated RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with AMV reverse transcriptase using the method of the manufacturer (Promega). Both cDNA and RNA treated with DNase I were subjected to PCR with forward primer 5′-ACAAGATCCGCAGACGTGTA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ACAGATGGCTGGCAACTAGA-3′. PCR amplification was initiated at 94°C for 4 minutes, 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, followed by final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. A band at 199 bp indicated VEGF165b transgene expression.

ELISA of VEGFxxxb

Tissue protein lysate was prepared from mouse kidney tissue in RIPA buffer. For cultured podocytes, conditioned medium from cells with or without transfection was used. Protein concentration was determined by Bio-Rad assay (Bio-Rad), and the amount of VEGF165b was determined by ELISA as described previously18 with a specific detection antibody against VEGFxxxb isoforms.

Briefly, 0.08 μg of goat anti-VEGF polyclonal IgG (AF293-NA; R&D Systems) diluted in 1× PBS (pH 7.4) was adsorbed onto each well of a 96-well plate (Immulon 2HB; Thermo Life Sciences, Basingstoke, UK) overnight at room temperature. The plate was washed three times between each step with 1× PBS-Tween (0.05%). After blocking with 100 μl of 5% BSA in PBS for 1 hour at 37°C, 100 μl of recombinant human VEGF165b (R&D Systems) diluted in 1% BSA in PBS (ranging from 62.5 pg/ml to 4.0 ng/ml) or protein samples was added to each well. After incubation for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking and three washes, 100 μl of mouse monoclonal anti-VEGFxxxb biotinylated IgG (clone 264610/1; R&D Systems) at 0.4 μg/ml was added to each well, and the plate was left for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking. A total of 100 μl of streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase (R&D Systems) at 1:200 dilution in 1% BSA in PBS was added; the plate was left at room temperature for 20 minutes, and 100 μl/well O-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride solution (substrate reagent pack DY-999; R&D Systems) was added. The plate was protected from light and incubated for 20 minutes at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 50 μl/well 1 M H2SO4, and absorbance was read immediately in the Opsys MR 96-well plate reader (Dynex Technologies, Chantilly, VA) at 492 nm, with control reading at 460 nm.

Glomerular Permeability

The normalized glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient (LpA/Vi) of isolated intact whole glomeruli was calculated using an oncometric technique described in detail by Salmon et al.23

Glomerular Isolation and Solutions

Mice aged between 8 and 10 months were killed by cervical dislocation, and kidneys were removed. Glomeruli were isolated in mammalian ringer solution containing 1% BSA using conventional techniques. The glomerular harvest retained by the 75-μm mesh sieve was kept on ice to preserve morphology. During isolation, the concentration of plasma proteins within the glomerular capillaries equilibrates with the surrounding solution. Perfusate containing either dilute BSA (1%) or concentrated BSA (8%) was made in mammalian ringer solution and adjusted to pH 7.45 ± 0.02.

Apparatus

Micropipettes were pulled from glass capillary tubes (outer diameter 1.2 mm; Clark Electromedical Instruments, Reading, UK). The 13-μm aperture tip was fitted within a rectangular cross-section glass microslide (inner diameter 400 μm × 4 mm; Camlab, Cambridge, UK). The microslide was visualized over the ×10 objective using an inverted microscope (Leica DM IL HC Fluo). A monochrome video camera (Hitachi KP-M3AP) was attached to the top of the microscope to permit recording of individual glomeruli loaded into the system. The video camera was connected through a digital timer (FOR.A VT33) to a videocassette recorder (Panasonic AG7350) and monochrome monitor (Sony SSM-125CE). Perfusates were held in elevated heated reservoirs connected to the microslide via tubing. A rapid-response remote tap (075P3; Bio-Chem Valve) controlled the choice of perfusate exciting the microslide. The fluid within the system was maintained at 37°C using a separate system of tubes and heating coils connected to a heated water bath.

Glomerular Volume Change

Glomeruli that were free of Bowman's capsule and arteriolar or tubular fragments were chosen for study. All glomerular observations were performed within 3 hours of nephrectomy. After a period of equilibration in flowing dilute perfusate (2 minutes), the rapid remote tap was switched, allowing the concentrated BSA to enter the microslide.

Analysis of Glomerular Volumetric Change

Perfusate switches were recorded on videotape, and sequences were reviewed off-line using Apple imovies (Apple USA) and an analog-to-digital converter (ADVC-300; Canopus). All measurements were done by an operator who was blind to the genotype or treatment. A sequence of images straddling the time point at which perfusate switch occurred was created. The glomerular image in each was replicated in Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems), and the area (Aμm2) was calculated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). Glomerular volume was derived from area measurements by substituting glomerular image area (A) into the formula

where r is glomerular radius, to reveal

Glomerular volume (nl) was plotted against time since the first appearance of the Schlieren phenomenon, marking the arrival of the new oncopressive perfusate. Two regression lines were then applied to these points. The slope of the first was set as 0 and applied to points before the solution switch when glomerular volume was stable. The two lines were calculated to meet at their break point. This point was defined as the time point at which glomerular volume begins to decline. The second line was applied to points covering a period of at least 0.04 second and no more than 0.1 second from the break point. Within these confines, the points at which the applied regression line had the greatest slope were chosen.

Calculation of LpA

The slope of the second regression line describes the greatest initial rate of glomerular volume change and can therefore be equated to the term Jv in the Starling equation:

The net hydrostatic pressures acting across an isolated glomerulus can be assumed to be negligible. Previous work suggested the reflection coefficient of an isolated glomerulus is not significantly different from 1.56 The Starling equation can therefore be rearranged to show that

in nl/min per mmHg, where ΔΠ is the difference between capillary and interstitial oncotic pressure.

Glomerular Volume and Glomerular Capillary Surface Area

The average glomerular volume in each animal was determined using the method described by Pagtulanan et al.57 Glomerular images were replicated in Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems), and the area (Aμm2) was calculated using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). In each animal, glomerular area was measured in at least 30 profiles from at least three different sections. Glomerular volume was calculated from the area measurements using the formula

where β is the shape coefficient for spheres (the idealized shape of glomeruli) and is equal to 1.38 and k is the size distribution coefficient and is equal to 1.157,58

The surface area of the glomerular capillary wall was determined from the surface density, using resin-embedded toluidine blue–stained kidney sections, as described previously.57,59 High-magnification light micrographs of whole glomeruli were opened in Photoshop, and a 10-mm2 grid was superimposed. The number of points (corners of grid squares) falling inside the glomerular profile (PGP) and the intercepts of the grid lines with the capillary wall (ICW) were counted. From these measurements, the surface density (Sv) was calculated using the equation

|

where k is the real length of the grid line segments. For each animal, Sv was determined in between three and six glomerular profiles. The average surface area of the glomerular capillary wall expressed in micrometers squared was then calculated as the product of the surface density and mean glomerular volume for each animal.

VEGF165b Experiments

In a separate group of experiments, glomeruli from WT C57/Blk6 mice were exposed to rhVEGF165b (PhiloGene). After isolation, glomeruli were incubated at 37°C in 1% BSA solution or 1% BSA solution containing either 40 pM of VEGF165b or 1 nM VEGF165b. Glomeruli from each solution were then individually loaded into the microslide, and the ultrafiltration coefficient was calculated as described already.

Phenotype and Histologic Analysis

A separate group of animals aged between 8 and 10 months were used to collect tissue, plasma, and urine for phenotypic and histologic analysis. Animals were individually housed in metabolic cages for up to 12 hours to obtain a urine sample. They were anesthetized using 5% isoflurane, and a blood sample was taken by direct cardiac puncture. Mice were then killed by cervical dislocation. The kidneys were removed, divided, and preserved by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde, 2.5% gluteraldehyde, or liquid nitrogen.

Immunohistochemistry

Kidney samples from WT, heterozygous, and homozygous mice were formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were mounted onto gelatin/poly-l-lysine–coated glass slides. The sections were dried onto the slides in a 37°C incubator overnight. Sections were dewaxed in Histoclear (RA Lamb, Eastbourne, UK) for 5 minutes and rehydrated through graded ethanol solutions (100, 90, and 70% vol/vol). Sagittal sections of all kidneys were cut and stained (hematoxylin and eosin). These were coded and reviewed by two assessors independently. Assessors were unaware of the origin of the section and could not distinguish between animals on glomerular size, mesangial matrix, glomerular cellular scores, or tubular morphology.

Microwave antigen retrieval was performed in 0.01 mM citric buffer, saturated sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0), for 7 minutes at 95°C at 800 W followed by 9 minutes at 120 W. Sections were cooled to room temperature before being washed twice in deionized water for 5 minutes each time. Sections were incubated with freshly prepared 3% vol/vol hydrogen peroxide (BDH, Poole, UK) diluted in 1× PBS for 5 minutes, then washed twice for 5 minutes with 1× PBS and blocked with 5% wt/vol BSA (Sigma) followed by 1.5% wt/vol normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories) in 5% wt/vol BSA for 30 minutes. The sections were washed twice with 0.05% vol/vol PBS-Tween at room temperature for 5 minutes, then incubated with the primary antibody diluted in 1.5% wt/vol normal goat serum in 1× PBS. A polyclonal rabbit VEGF antibody (A20 sc152; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was used. Tissue sections were treated with a matched concentration of normal, affinity-purified rabbit IgG (Sigma) used as a negative control. The sections were washed twice in 0.05% vol/vol PBS-Tween, for 5 minutes each time. The blocking step was repeated as before, followed by two 5-minute washes in 0.05% vol/vol PBS-Tween. All sections, including the controls, were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories) diluted in 1.5% wt/vol normal goat serum for 1 hour in a humid chamber at room temperature. Sections were washed twice with 0.05% vol/vol PBS-Tween, 5 minutes per wash, then incubated with a prepared avidin-biotinylated enzyme complete kit (Vector Laboratories) for 45 minutes in a humid chamber at room temperature. Again, the sections were washed twice with 0.05% vol/vol PBS-Tween, 5 minutes each time, followed by incubation with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine substrate (Vector Laboratories) to yield a brown-colored product. The reaction was stopped by washing twice with deionized water for 5 minutes. Sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin (BDH) for 5 minutes, then differentiated in water. Sections were dehydrated by passing through increasing concentrations of ethanol (70, 90, and 100% vol/vol) for at least 2 minutes each, cleared in xylene for at least 10 minutes, and permanently mounted in DPX mountant for histology. Staining was examined with a Nikon Eclipse E-400 microscope; images were captured using a DCN-100 digital imaging system (Nikon Instruments).

EM Analysis

Kidney fixation procedures were adapted and modified from Hayat.60 Portions of kidney from each mouse were rapidly excised and sliced in a pool of glutaraldehyde fixative (2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer [pH 7.3], 4 to 8°C). Cubes (0.5 to 1.0-mm diameter) of kidney cortex were further fixed at 4°C with glutaraldehyde fixative. After a minimum of 3 hours of fixation, the tissues were left in fresh fixative overnight, then washed in cacodylate buffer postfixed for 1 hour in osmium (1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer [pH 7.3, 4°C]). Tissues were washed in cacodylate buffer and then distilled water before ethanol dehydration, infiltration, and embedding in Araldite resin (Agar Scientific, Stansted, UK). Glomeruli were identified from 0.5 μm of toluidine blue–stained survey sections. Glomeruli were cut at 70 to 100 nm thick for EM observation. Analysis was conducted on digital electron micrographs (taken at ×890 and ×2900). Measurements were made of percentage of coverage of the GFB by the SPS, thickness of the GBM, height of SPS, foot process width (or separation between slit diaphragms), and separation between endothelial fenestrations and width of fenestrations. Linear measurements from electron micrographs were made at random points using a Photoshop grid. To clarify changes in fenestrations, 40-nm sections were used.

Glomerular Filtration Rate

GFR was determined in anesthetized 9-month-old heterozygous and age-matched littermate controls using a single bolus injection of FITC-Inulin.

Statistical Analysis

Data are means ± SE. P < 0.05 was regarded as significant. Methods of statistical analysis are included in relevant figure legend.

Disclosures

Intellectual property relating to DSS VEGF isoforms is owned by the University of Bristol.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG08/022/21636, FS/05/114/19959, FS/04/09, BS/06/005, and FS/07/059/24071), the Medical Research Council (GR0600920), Wellcome Trust (69134, 69029), and Richard Bright VEGF Research Trust.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “What Type of VEGF Do You Need?” on pages 1410–1412.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 289: 2560–2572, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gerstein HC, Mann JF, Yi Q, Zinman B, Dinneen SF, Hoogwerf B, Halle JP, Young J, Rashkow A, Joyce C, Nawaz S, Yusuf S: Albuminuria and risk of cardiovascular events, death, and heart failure in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals. JAMA 286: 421–426, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinto-Sietsma SJ, Janssen WM, Hillege HL, Navis G, De Zeeuw D, De Jong PE: Urinary albumin excretion is associated with renal functional abnormalities in a nondiabetic population. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1882–1888, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feng D, Nagy JA, Brekken RA, Pettersson A, Manseau EJ, Pyne K, Mulligan R, Thorpe PE, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM: Ultrastructural localization of the vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) receptor-2 (FLK-1, KDR) in normal mouse kidney and in the hyperpermeable vessels induced by VPF/VEGF-expressing tumors and adenoviral vectors. J Histochem Cytochem 48: 545–556, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foster RR, Hole R, Anderson K, Satchell SC, Coward RJ, Mathieson PW, Gillatt DA, Saleem MA, Bates DO, Harper SJ: Functional evidence that vascular endothelial growth factor may act as an autocrine factor on human podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F1263–F1273, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eremina V, Sood M, Haigh J, Nagy A, Lajoie G, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Kikkawa Y, Miner JH, Quaggin SE: Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J Clin Invest 111: 707–716, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oltean S, Neal CR, Salmon A, Quaggin SE, Harper SJ, Bates DO: VEGF over-expression increases glomerular water permeability in vivo in a conditional and inducible mouse model [Abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 71A, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, Hwu P, Schwartzentruber DJ, Topalian SL, Steinberg SM, Chen HX, Rosenberg SA: A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med 349: 427–434, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, Hochster H, Haas M, Weisstuch J, Richardson C, Kopp JB, Kabir MG, Backx PH, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Barisoni L, Alpers CE, Quaggin SE: VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med 358: 1129–1136, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. de Vriese AS, Tilton RG, Elger M, Stephan CC, Kriz W, Lameire NH: Antibodies against vascular endothelial growth factor improve early renal dysfunction in experimental diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 993–1000, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sugimoto H, Hamano Y, Charytan D, Cosgrove D, Kieran M, Sudhakar A, Kalluri R: Neutralization of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by anti-VEGF antibodies and soluble VEGF receptor 1 (sFlt-1) induces proteinuria. J Biol Chem 278: 12605–12608, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ostendorf T, Kunter U, Eitner F, Loos A, Regele H, Kerjaschki D, Henninger DD, Janjic N, Floege J: VEGF(165) mediates glomerular endothelial repair. J Clin Invest 104: 913–923, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, Shields JD, Peat D, Gillatt D, Harper SJ: VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 62: 4123–4131, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harper SJ, Bates DO: VEGF-A splicing: The key to anti-angiogenic therapeutics? Nat Rev Cancer 8: 880–887, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qiu Y, Bevan H, Weeraperuma S, Wratting D, Murphy D, Neal CR, Bates DO, Harper SJ: Mammary alveolar development during lactation is inhibited by the endogenous antiangiogenic growth factor isoform, VEGF165b. FASEB J 22: 1104–1112, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rennel ES, Waine E, Guan H, Schuler Y, Leenders W, Woolard J, Sugiono M, Gillatt D, Kleinerman ES, Bates DO, Harper SJ: The endogenous anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform, VEGF(165)b inhibits human tumour growth in mice. Br J Cancer 98: 1250–1257, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rennel ES, Hamdollah-Zadeh MA, Wheatley ER, Magnussen A, Schuler Y, Kelly SP, Finucane C, Ellison D, Cebe-Suarez S, Ballmer-Hofer K, Mather S, Stewart L, Bates DO, Harper SJ: Recombinant human VEGF165b protein is an effective anti-cancer agent in mice. Eur J Cancer 44: 1883–1894, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Varey AH, Rennel ES, Qiu Y, Bevan HS, Perrin RM, Raffy S, Dixon AR, Paraskeva C, Zaccheo O, Hassan AB, Harper SJ, Bates DO: VEGF(165)b, an antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoform, binds and inhibits bevacizumab treatment in experimental colorectal carcinoma: Balance of pro- and antiangiogenic VEGF-A isoforms has implications for therapy. Br J Cancer 98: 1366–1379, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, Pritchard-Jones RO, Cui TG, Sugiono M, Waine E, Perrin R, Foster R, Digby-Bell J, Shields JD, Whittles CE, Mushens RE, Gillatt DA, Ziche M, Harper SJ, Bates DO: VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: Mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res 64: 7822–7835, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bevan HS, van den Akker NM, Qiu Y, Polman JA, Foster RR, Yem J, Nishikawa A, Satchell SC, Harper SJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Bates DO: The alternatively spliced anti-angiogenic family of VEGF isoforms VEGFxxxb in human kidney development. Nephron Physiol 110: 57–67, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lambrechts D, Storkebaum E, Morimoto M, Del-Favero J, Desmet F, Marklund SL, Wyns S, Thijs V, Andersson J, van Marion I, Al-Chalabi A, Bornes S, Musson R, Hansen V, Beckman L, Adolfsson R, Pall HS, Prats H, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P, Katayama S, Awata T, Leigh N, Lang-Lazdunski L, Dewerchin M, Shaw C, Moons L, Vlietinck R, Morrison KE, Robberecht W, Van Broeckhoven C, Collen D, Andersen PM, Carmeliet P: VEGF is a modifier of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in mice and humans and protects motoneurons against ischemic death. Nat Genet 34: 383–394, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Foster RR, Saleem MA, Mathieson PW, Bates DO, Harper SJ: Vascular endothelial growth factor and nephrin interact and reduce apoptosis in human podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F48–F57, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salmon AH, Neal CR, Bates DO, Harper SJ: Vascular endothelial growth factor increases the ultrafiltration coefficient in isolated intact Wistar rat glomeruli. J Physiol 570: 141–156, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ichimura K, Stan RV, Kurihara H, Sakai T: Glomerular endothelial cells form diaphragms during development and pathologic conditions. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1463–1471, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rostgaard J, Qvortrup K: Sieve plugs in fenestrae of glomerular capillaries: site of the filtration barrier? Cells Tissues Organs 170: 132–138, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Satchell SC, Braet F: Glomerular endothelial cell fenestrations: An integral component of the glomerular filtration barrier. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F947–F956, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Neal CR, Crook H, Bell E, Harper SJ, Bates DO: Three-dimensional reconstruction of glomeruli by electron microscopy reveals a distinct restrictive urinary subpodocyte space. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 1223–1235, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Neal CR, Muston PR, Njegovan D, Verrill R, Harper SJ, Deen WM, Bates DO: Glomerular filtration into the subpodocyte space is highly restricted under physiological perfusion conditions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1787–F1798, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salmon AH, Toma I, Sipos A, Muston PR, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Neal CR, Peti-Peterdi J: Evidence for restriction of fluid and solute movement across the glomerular capillary wall by the subpodocyte space. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1777–F1786, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Salmon AH, Neal CR, Harper SJ: New aspects of glomerular filtration barrier structure and function: five layers (at least) not three. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 197–205, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Perrin RM, Harper SJ, Bates DO: A role for the endothelial glycocalyx in regulating microvascular permeability in diabetes mellitus. Cell Biochem Biophys 49: 65–72, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eremina V, Baelde HJ, Quaggin SE: Role of the VEGF: A signaling pathway in the glomerulus: Evidence for crosstalk between components of the glomerular filtration barrier. Nephron Physiol 106: 32–37, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bates DO, Curry FE: Vascular endothelial growth factor increases hydraulic conductivity of isolated perfused microvessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H2520–H2528, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gavard J, Patel V, Gutkind JS: Angiopoietin-1 prevents VEGF-induced endothelial permeability by sequestering Src through mDia. Dev Cell 14: 25–36, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Glass CA, Harper SJ, Bates DO: The anti-angiogenic VEGF isoform VEGF165b transiently increases hydraulic conductivity, probably through VEGF receptor 1 in vivo. J Physiol 572: 243–257, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hillman NJ, Whittles CE, Pocock TM, Williams B, Bates DO: Differential effects of vascular endothelial growth factor-C and placental growth factor-1 on the hydraulic conductivity of frog mesenteric capillaries. J Vasc Res 38: 176–186, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Katavetin P: VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med 359: 205–206, author reply 206–207, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davis B, Dei Cas A, Long DA, White KE, Hayward A, Ku CH, Woolf AS, Bilous R, Viberti G, Gnudi L: Podocyte-specific expression of angiopoietin-2 causes proteinuria and apoptosis of glomerular endothelia. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2320–2329, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ding M, Cui S, Li C, Jothy S, Haase V, Steer BM, Marsden PA, Pippin J, Shankland S, Rastaldi MP, Cohen CD, Kretzler M, Quaggin SE: Loss of the tumor suppressor Vhlh leads to upregulation of Cxcr4 and rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in mice. Nat Med 12: 1081–1087, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Foster RR: The importance of cellular VEGF bioactivity in the development of glomerular disease. Nephron Exp Nephrol 113: e8–e15, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Laurinavicius A, Hurwitz S, Rennke HG: Collapsing glomerulopathy in HIV and non-HIV patients: A clinicopathological and follow-up study. Kidney Int 56: 2203–2213, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kamba T, Tam BY, Hashizume H, Haskell A, Sennino B, Mancuso MR, Norberg SM, O'Brien SM, Davis RB, Gowen LC, Anderson KD, Thurston G, Joho S, Springer ML, Kuo CJ, McDonald DM: VEGF-dependent plasticity of fenestrated capillaries in the normal adult microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H560–H576, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roberts WG, Palade GE: Increased microvascular permeability and endothelial fenestration induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. J Cell Sci 108: 2369–2379, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bevan HS, Harper SJ, Bates DO: Vascular endothelial growth factors. In: Angiogenesis: Basic Science and Clinical Applications, edited by Maragoudakis ME, Papadimitriou E, Kerala, India, Transworld Research Network, 2007, pp 31–54 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Konopatskaya O, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Gardiner TA: VEGF165b, an endogenous C-terminal splice variant of VEGF, inhibits retinal neovascularization in mice. Mol Vis 12: 626–632, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cebe Suarez S, Pieren M, Cariolato L, Arn S, Hoffmann U, Bogucki A, Manlius C, Wood J, Ballmer-Hofer K: A VEGF-A splice variant defective for heparan sulfate and neuropilin-1 binding shows attenuated signaling through VEGFR-2. Cell Mol Life Sci 63: 2067–2077, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kawamura H, Li X, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Claesson-Welsh L: Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A165b is a weak in vitro agonist for VEGF receptor-2 due to lack of coreceptor binding and deficient regulation of kinase activity. Cancer Res 68: 4683–4692, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schumacher VA, Jeruschke S, Eitner F, Becker JU, Pitschke G, Ince Y, Miner JH, Leuschner I, Engers R, Everding AS, Bulla M, Royer-Pokora B: Impaired glomerular maturation and lack of VEGF165b in Denys-Drash syndrome. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 719–729, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kawachi H, Koike H, Kurihara H, Yaoita E, Orikasa M, Shia MA, Sakai T, Yamamoto T, Salant DJ, Shimizu F: Cloning of rat nephrin: Expression in developing glomeruli and in proteinuric states. Kidney Int 57: 1949–1961, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moeller MJ, Kovari IA, Holzman LB: Evaluation of a new tool for exploring podocyte biology: Mouse Nphs1 5′ flanking region drives LacZ expression in podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2306–2314, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Nowak DG, Woolard J, Amin EM, Konopatskaya O, Saleem MA, Churchill AJ, Ladomery MR, Harper SJ, Bates DO: Expression of pro- and anti-angiogenic isoforms of VEGF is differentially regulated by splicing and growth factors. J Cell Sci 121: 3487–3495, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smith CW, Valcarcel J: Alternative pre-mRNA splicing: The logic of combinatorial control. Trends Biochem Sci 25: 381–388, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Morrison AA, Viney RL, Saleem MA, Ladomery MR: New insights into the function of the Wilms tumor suppressor gene WT1 in podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F12–F17, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Quaggin SE, Kreidberg JA: Development of the renal glomerulus: Good neighbors and good fences. Development 135: 609–620, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Saleem MA, O'Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P: A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 630–638, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Savin VJ, Terreros DA: Filtration in single isolated mammalian glomeruli. Kidney Int 20: 188–197, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Pagtalunan ME, Rasch R, Rennke HG, Meyer TW: Morphometric analysis of effects of angiotensin II on glomerular structure in rats. Am J Physiol 268: F82–F88, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Weibel ER: Stereological Methods: Practical Methods for Biological Morphometry, London, London Academic, 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Osterby R, Gundersen HJ: Fast accumulation of basement membrane material and the rate of morphological changes in acute experimental diabetic glomerular hypertrophy. Diabetologia 18: 493–500, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hayat MA, ed.: Chemical Fixation, London, Macmillan, 1989, pp 311–315, [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.