Abstract

Objective:

Motor signs are functionally disabling features of Huntington disease. Characteristic motor signs define disease manifestation. Their severity and onset are assessed by the Total Motor Score of the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale, a categorical scale limited by interrater variability and insensitivity in premanifest subjects. More objective, reliable, and precise measures are needed which permit clinical trials in premanifest populations. We hypothesized that motor deficits can be objectively quantified by force-transducer-based tapping and correlate with disease burden and brain atrophy.

Methods:

A total of 123 controls, 120 premanifest, and 123 early symptomatic gene carriers performed a speeded and a metronome tapping task in the multicenter study TRACK-HD. Total Motor Score, CAG repeat length, and MRIs were obtained. The premanifest group was subdivided into A and B, based on the proximity to estimated disease onset, the manifest group into stages 1 and 2, according to their Total Functional Capacity scores. Analyses were performed centrally and blinded.

Results:

Tapping variability distinguished between all groups and subgroups in both tasks and correlated with 1) disease burden, 2) clinical motor phenotype, 3) gray and white matter atrophy, and 4) cortical thinning. Speeded tapping was more sensitive to the detection of early changes.

Conclusion:

Tapping deficits are evident throughout manifest and premanifest stages. Deficits are more pronounced in later stages and correlate with clinical scores as well as regional brain atrophy, which implies a link between structure and function. The ability to track motor phenotype progression with force-transducer-based tapping measures will be tested prospectively in the TRACK-HD study.

GLOSSARY

- CoV

= coefficient of variation;

- DBS

= disease burden score;

- Freq

= frequency;

- HD

= Huntington disease;

- ICV

= intracranial volume;

- IOI

= interonset interval;

- ΔIOI

= deviation from interonset interval;

- IPI

= interpeak interval;

- ΔIPI

= deviation from interpeak interval;

- ITI

= intertap interval;

- log

= logarithmic;

- MT

= metronome tapping;

- ΔMTI

= deviation from midtap interval;

- preHD

= premanifest Huntington disease;

- RT

= reaction time;

- ST

= speeded tapping;

- TD

= tap duration;

- TF

= tapping force;

- TFC

= Total Functional Capacity;

- UHDRS

= Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale;

- UHDRS-TMS

= Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale-Total Motor Score;

- VBM

= voxel-based morphometry.

Huntington disease (HD) is an autosomal dominant neurodegenerative disorder. Motor deficits, such as chorea, bradykinesia, and dystonia, are ascribed to basal ganglia dysfunction.1 Nevertheless, widespread cortical2 and white matter3,4 loss develop, contributing to the complex clinical phenotype and functional decline observed in HD.5

Initial changes in HD gene carriers are detected years before diagnosis6,7 favoring an early introduction of disease-modifying therapies. Motor signs are amenable to quantitative assessment and may provide objective measures for disease onset and progression. Several quantitative motor tasks, including force-transducer-based assessments, detect deficits in premanifest gene carriers.7–9 In tapping tests, they were related to predicted time to diagnosis.6 Correlations with the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale-Total Motor Score (UHDRS-TMS) and its arm subscore were observed; performance deteriorated during a 3-year follow-up in manifest HD.10

These results support further exploration of quantitative tapping assessments in HD. We used precalibrated sensors to assess isometric tapping forces standardized across 4 centers. Recording forces permits 1) accurate evaluation of tap initiation (avoiding delays caused by vertical movements in button-pressing devices and the omission of taps through incomplete depression) and 2) definition of new variables of tapping performance derived from force evolution or peaks. Automated evaluation routines provide a standardized readout. We hypothesized that deficits in a speeded and a metronome tapping task are detectable in premanifest and early symptomatic HD, and correlate with 1) disease burden, 2) clinical motor signs of HD, 3) regional gray and white matter atrophy, and 4) cortical thinning.

METHODS

Subjects.

A total of 123 patients with early HD (HD), 120 premanifest gene carriers (preHD), and 123 control subjects were recruited in 4 centers (Leiden, London, Paris, Vancouver) as part of the biomarker study TRACK-HD.7 Selection criteria for preHD included a Disease Burden Score (DBS = [CAG repeat − 35.5] × age)11 >250 and a UHDRS-TMS ≤5 at the screening visit. All gene carriers required a CAG expansion of ≥40 repeats. PreHD was further split at the median of years until predicted disease manifestation, i.e., 10.8 years, into preHD-A and preHD-B,12 early manifest participants into stages 1 (HD1) and 2 (HD2) according to their Total Functional Capacity (TFC) scores.13 Control subjects were age- and gender-matched to the combined gene-positive group and required negative genetic testing if at risk for HD. Gene-positive participants were assessed clinically using the UHDRS-TMS. Handedness was determined according to the Edinburgh Inventory14; ambidextrous subjects were considered right-handed. See table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org for demographics; more detailed information can be found elsewhere.7

Standard protocol approvals and patient consents.

The study was approved by all local ethical standards committees on human experimentation; written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Tapping.

The tapping apparatus was equipped with precalibrated and temperature-controlled force sensors (Mini-40, ATI) covered with sandpaper. Normal forces were recorded at 0.025 N resolution and 400 Hz sampling frequency. WINSC/WINZOOM software (University of Umeå, Sweden) was used for recording and data analysis. A high-pitched tone of 0.25 s duration served as cue. Subjects placed their nondominant hands on a rest, the index finger above the force-transducer (figure 1A). Recording started after practice periods.

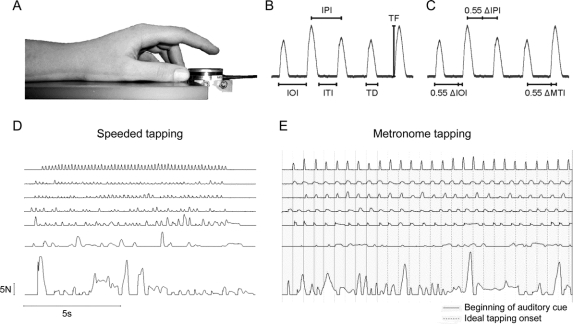

Figure 1 Data acquisition, variables, and examples

(A) Setup of the tapping device and position of hand and index finger in relation to the force-transducer. (B) Definitions of measures for speeded tapping (IOI = interonset interval; IPI = interpeak interval; ITI = intertap interval; TD = tap duration; TF = tap force) and (C) additional measures in metronome tapping (ΔIOI = deviation from IOI = IOI − 0.55 s, ΔIPI = deviation from IPI = IPI − 0.55 s, ΔMTI = midtap interval = [interval time between the arithmetic middles of 2 consecutive taps] − 0.55). (D, E) Finger tapping shows deterioration in advanced stages of Huntington disease. A range of sample recordings from (top to bottom) good to poor performance are given for (D) speeded tapping and (E) metronome tapping—the solid gray lines represent the onset of auditory cues in metronome tapping, the continued dashed lines mark the ideal rate after cues stopped.

Speeded tapping required maximal possible velocity between 2 cues. In metronome tapping, subjects were presented with 10 auditory pacing tones at 1.8 Hz (0.55 s intercue interval) and instructed to harmonize their fingertaps with the pacing tones. A self-paced phase of 10 seconds followed and ended with another auditory cue. Subjects performed five 10-second trials in both conditions (figure 1, D and E).

Quality control and analyses were performed centrally and blinded to subject groupings. Automated routines were created for data evaluation in WINZOOM and Visual Basics for Applications in Excel®. Statistical analyses were performed by an independent, centralized team of statisticians.

The beginning of a tap was defined as a rise of the force by 0.05 N above maximal baseline level. The tap ended when it dropped to 0.05 N before the maximal baseline level was reached again. Metronome tapping analysis was solely based on the self-paced period of the trial.

The variability of tap durations (TD), interonset intervals (IOI), interpeak intervals (IPI), and intertap intervals (ITI) were the primary outcome measures for speeded tapping (figure 1B). In addition, variability of peak tapping forces (TF) was calculated as coefficient of variation, and the tapping frequency (Freq), i.e., the number of taps between the onsets of the first and the last tap divided by the time in between, were determined.

For the metronome task, TD, ITI, and TF were analogously defined (figure 1C). Furthermore, the intercue interval was subtracted from the IPIs (ΔIPI), the interval between the midpoints (ΔMTI, i.e., the tapping measure published in Tabrizi et al.7), and the onsets (ΔIOI) of 2 consecutive taps. The reaction time (RT) until the onset of the first tap was calculated.

MRI.

All participants underwent 3-T MRI scans with standardized protocols for Siemens and Phillips scanners. Volumetric brain measures included striatal and total intracranial volume (ICV), voxel-based morphometry (VBM), and cortical thickness (assessed by Freesurfer). Details can be found elsewhere.7 Only explicitly right-handed subjects were included in imaging analyses as a lack of symmetry in left- and right-handed subjects has been suggested.15 Freesurfer methods are optimized for Siemens scanners, therefore cortical thickness correlations only included the scans of 2 sites.

Statistics.

In this cross-sectional analysis, the 5 subgroups (control, preHD-A, preHD-B, HD1, and HD2) were the a priori predictor variables of interest for all speeded and metronome tapping measures. Potential confounders (i.e., age, gender, study site, and education level) were controlled for in all formal analyses. We estimated adjusted differences among groups and subgroups using linear models. Furthermore, in the case of outcomes originally measured as SDs of mean performance, we performed logarithmic and inversed transformations prior to analyses. These transformations greatly improved concordance with standard normality assumptions for linear model inference. Although inversed transforms have been used in previous similar analyses,6,7 we focus on logarithmic transforms, since they constantly yielded better mathematical assumptions for model inference.

Associations between tapping measures, the UHDRS-TMS, TFC, and DBS were analyzed by Pearson correlation for the preHD, HD, and a combined gene-positive group. For premanifest participants, measures were correlated to probability of estimated disease onset within 5 years according to Langbehn et al.'s parametric model12,16 and for all gene-positive participants to the ratio of striatal to intracranial volume (striatal/ICV) by a least squares regression model.

A hypothesis-free analysis was performed to identify correlation between regional atrophy assessed in VBM and tapping impairment in the combined gene-positive group. A multiple regression model was used with age, gender, ICV, and disease burden, accounting for disease severity, as covariates. An explicit mask generated using the optimal thresholding technique17 was used to specify the location of statistical testing. Results are reported corrected for familywise error, at the p < 0.05 level.

Similarly, the amount of cortical thickness decrease was correlated with selected tapping measures in a subgroup consisting of all gene-positive subjects scanned by Siemens MRI machines. A surface-based regression analysis was used, with age, gender, and disease burden as covariates. Each score was modeled independently, using a model of the thickness for each subtest [offset + (slope × motor score) + (slope × age) + an error term]. The offset and slope are subject-independent regression coefficients estimated separately for each vertex using a general linear model. t Statistics at each vertex were used to test the hypothesis that the slope coefficient was equal to zero. Results are reported corrected for a false discovery rate at the p < 0.01 level.

RESULTS

Between-group and -subgroup comparisons.

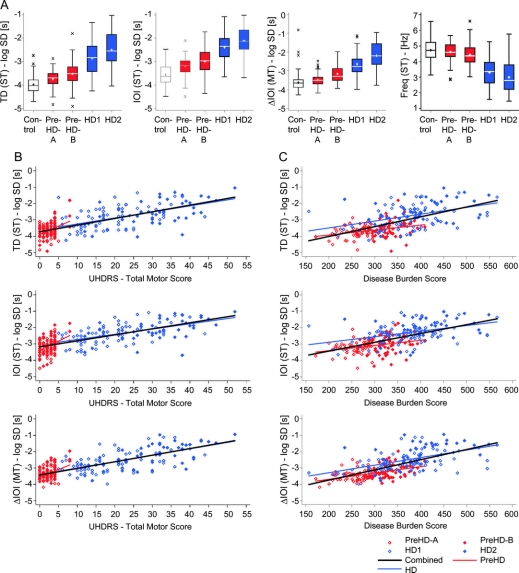

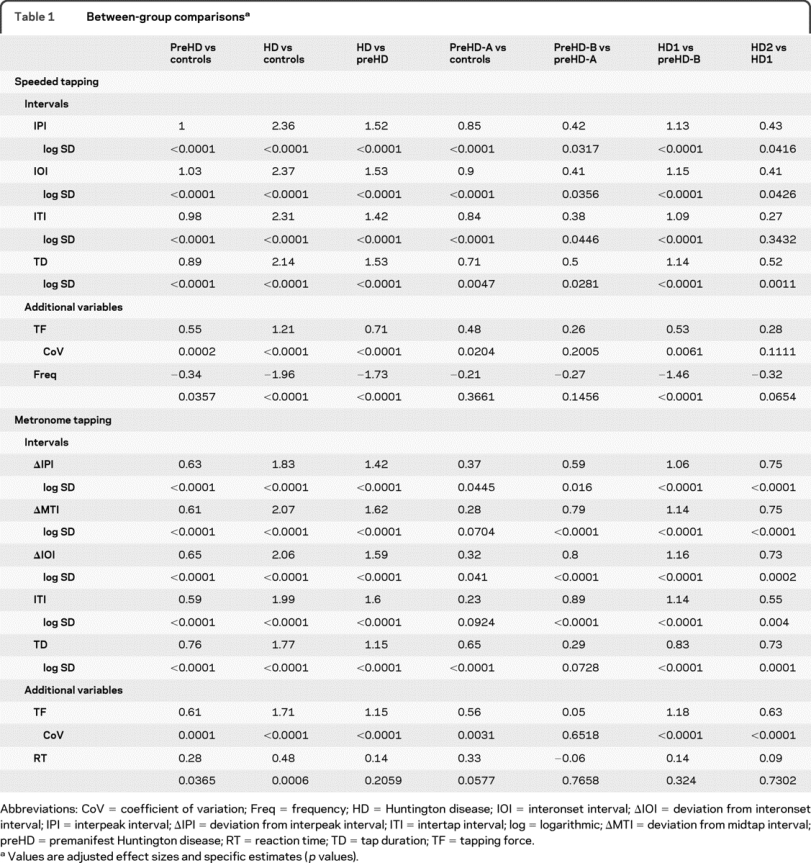

All speeded tapping intervals (IPI, IOI, ITI, and TD) distinguished at p < 0.0001 throughout groups and delineated all subgroups with one exception: ITI in HD2 vs HD1 was not significant (table 1, table e-2, and figure 2A). Speeded tapping intervals best distinguished the preHD-A group from controls with the highest effect size for IOI. Best subgroup differentiation was observed for HD1 vs preHD-B. Peak TF distinguished between groups, although with lower effect sizes, but not between all subgroups. The tapping frequency also did not differentiate all subgroups, but exhibited the strongest effect size at the threshold between HD1 and preHD-B (figure 2A).

Table 1 Between-group comparisons

Figure 2 Box plots and correlation analysis of selected tapping items by subgroups

(A) Unadjusted results of the nondominant hand of tap duration (TD) (speeded tapping [ST]), interonset interval (IOI) (ST), deviation from interonset interval (ΔIOI) (metronome tapping [MT]), and frequency (Freq – ST). Correlations between tapping variables and (B) Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale-Total Motor Score and (C) Disease Burden Score (DBS = [CAG repeat – 35.5] × age).11 Correlations are displayed for TD (ST), IOI (ST), and ΔIOI (MT). For r values, please see table 2. HD = Huntington disease.

All metronome tapping intervals (ΔIPI, ΔMTI, ΔIOI, ITI, and TD) differentiated all groups (p < 0.0001). Each subgroup distinction was made at p < 0.0001, however, by different variables. ΔMTI and ITI in preHD-A vs controls and TD in preHD-B vs preHD-A did not reach significance. ΔIOI performed well throughout all group and subgroup comparisons. Metronome tapping intervals better distinguished preHD-B vs preHD-A and HD2 vs HD1 compared to speeded tapping. Again, best subgroup differentiation was observed for HD1 vs preHD-B. TF reached significance for all group and subgroup comparisons except preHD-B vs preHD-A. The reaction time did not distinguish HD vs preHD or any subgroups.

We did not observe interactions between study site and subgroup for any of the variables.

DBS and UHDRS-TMS correlations.

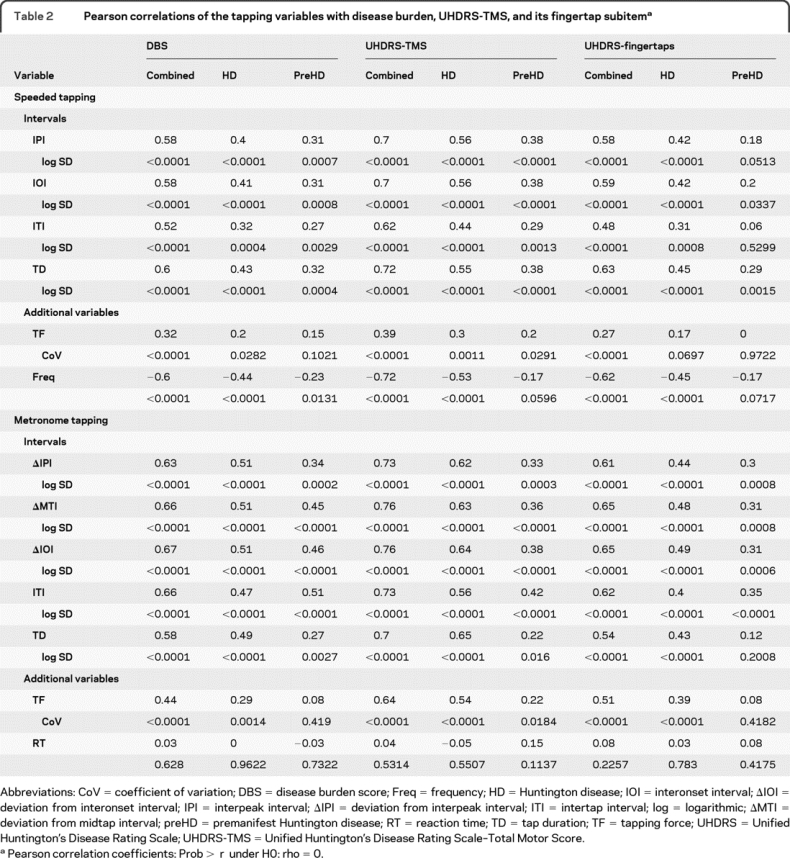

The variability of all speeded tapping intervals correlated with the DBS and UHDRS-TMS in all groups. The correlations to the fingertap subscore were significant for the combined gene-positive (HD + preHD) and the HD group but mostly failed significance for preHD. The combined group presented higher r values than the HD or preHD group. Correlations to the UHDRS-TMS were slightly higher than to the DBS or UHDRS-TMS fingertap subscore. TD showed strongest correlations to nearly all scores. Correlations of TF variability (CoV) to UHDRS-TMS and DBS were weaker than those of the interval variables, the preHD results did not correlate to the DBS, and only the combined group showed correlations to the UHDRS-fingertap subitem. The tapping frequency correlated well with the UHDRS scores and DBS in the HD and combined groups; preHD results were only correlated to the DBS.

Variability of metronome tapping intervals correlated with DBS, UHDRS-TMS (figure 2, B and C), and UHDRS-TMS fingertaps throughout groups with an exception in TD for the preHD group (table 2). Metronome tapping correlations were strongest in the combined group. TF variability performed weaker than the interval measures, the preHD results only correlated with the UHDRS-TMS. Reaction time was not correlated to disease burden or motor scores at all.

Table 2 Pearson correlations of the tapping variables with disease burden, UHDRS-TMS, and its fingertap subitem

Associations with other measures.

Linear models showed an association between nearly all investigated variables and estimated disease onset within 5 years (p < 0.0001) in the premanifest group.12,16 The performance of the gene-positive subjects was associated with the ratio striatal/ICV (p < 0.0001). The reaction time was the only variable that did not reveal either association.

Imaging correlations.

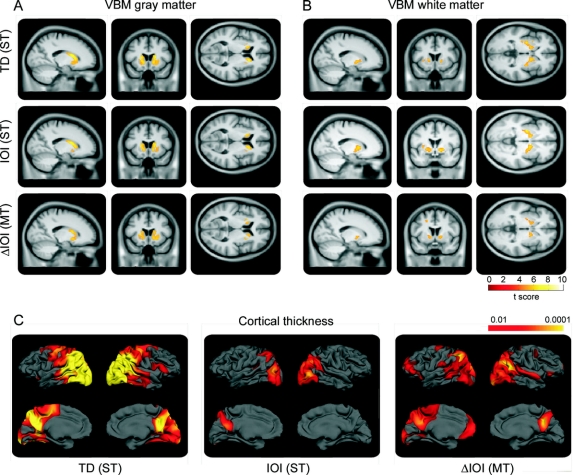

Objective whole-brain correlations between tapping variability and brain volumes as observed by VBM revealed highly significant correlations across the combined gene-positive group (figure 3, A and B, and figure e-1). Increased TD variability correlated with gray matter atrophy bilaterally in the caudate and putamen and to a lesser extent with the right superior temporal and the left precentral gyrus. TD variability also correlated with bilateral loss of the internal and external capsule and the white matter of the superior temporal gyrus. Increased IOI variability was primarily associated with atrophy of the caudate and putamen bilaterally with slightly more involvement of the right side; an association was also seen with a small region of the right superior temporal gyrus. IOI variability correlated with the internal capsule bilaterally, the left external capsule, the right superior temporal, and the left frontal subgyral white matter. Increased ΔIOI variability correlated with gray matter loss of the caudate and putamen. Also white matter loss correlated with increased ΔIOI variability in the extrastriatal white matter including the internal capsule, as well as the left subgyral white matter of the frontal lobe.

Figure 3 Structural brain correlations to tapping performance

(A-C) Statistical parametric map showing correlations between tap duration (TD) (speeded tapping [ST]), interonset interval (IOI) (ST), and deviation from interonset interval (ΔIOI) (metronome tapping [MT]) with gray (A) and white matter (B) in voxel-based morphometry (VBM) (results overlaid on a mean image from this dataset are shown, thresholded at p < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons using familywise error) and (C) cortical thickness (results are corrected for a false discovery rate at p < 0.01).

Surface-based correlation analysis of tapping measures with changes in cortical thickness revealed correlations between the variability observed in tapping and cortical thickness diminution across the 2 Siemens scanners (figure 3C). In speeded tapping, variability of TD and IOI were both correlated with loss of cortical thickness. Strongest correlations were seen for TD, primarily in the occipital, parietal, and primary motor cortex. IOI correlations were weaker and limited to occipital and parietal regions. Similar results were observed for ΔIOI in metronome tapping in the occipito-parietal region, while additional correlations were observed in the frontal cortex.

DISCUSSION

Force-transducer-based tapping objectively quantified motor deficits in premanifest and symptomatic HD gene carriers and distinguished between all groups and subgroups. Correlations to disease burden, UHDRS-TMS, and the reduction of brain volume in VBM and cortical thickness were demonstrated, suggesting a link between structure and function. Our results extend earlier findings on tapping deficits in HD. Paulsen et al.6 reported timing deficits in a tapping task up to a decade before predicted disease onset in a premanifest cohort. Tapping deficiencies in manifest HD and their correlation to the UHDRS-TMS have been described in smaller cohorts.18,19 Deficits are reproducible in repeated measurements19 and progress over time in manifest HD.10,19

TRACK-HD assessed a large cohort of premanifest and symptomatic gene carriers and controls. The UHDRS-TMS commonly serves as a primary or secondary outcome measure in clinical trials. However, the UHDRS-TMS is a categorical scale with limited sensitivity. It is susceptible to subjective error and interrater variability20,21 and was designed for manifest HD.22 Many studies define premanifest HD by a UHDRS-Diagnostic Confidence Level of 3 or lower. Subjects with up to 98% diagnostic certainty for manifest HD—based on the presence of characteristic motor signs—are thus considered premanifest. Accordingly, premanifest subjects may show noticeable motor signs with an impact on motor task performance. Study requirements in TRACK-HD limited clinical motor signs to a marginally noticeable level. Minor signs (UHDRS-TMS ≤5) were tolerated since instilled behavior has been reported in gene-negative offspring of HD families.20 Accordingly, gene-negative family members in the PREDICT-HD study exhibited a mean UHDRS-TMS of 2.41 (SD 3.06).23

The index finger is crucial for many fine motor tasks and thus well-trained, minimizing the potential impact of motor learning. Variability of motor task execution has been observed in several tasks, e.g., grasping,24,25 tongue protrusion,7 gait,26 and reaching.9 Accordingly, variability of motor coordination appears to be a characteristic sign of HD.

Motor timing is another substantial component of motor coordination and thus precise motor functioning. There is also evidence for increased timing variability in HD,27 even in a premanifest state.28 Higher variability of isometric contraction duration was interpreted as an impairment of the speed control system in manifest HD.29 Impaired time estimation in premanifest gene carriers correlated with the estimated years until onset.30 Both speeded and metronome tapping assessments require motor timing efforts. However, the tasks were designed to be relatively simple, not only to be easily applicable in various settings, but also minimizing the impact of working memory dysfunction, which occurs in HD.31 Demanding more attention, the metronome tapping task could be more influenced by memory dysfunction and cognitive deficits than the speeded tapping task. Nevertheless, both tasks detected deficits in tapping across all subgroups.

TRACK-HD provides the unique opportunity to correlate motor performance with structural brain changes employing 2 complementary imaging techniques under standardized, blinded conditions. We acknowledge that cortical thickness data were limited to 2 sites using Siemens scanners to avoid differing image contrast and variation in segmentation routines. Also, different methods for multiple comparison correction were used for the 2 techniques, which may partially account for lacking cortical correlations in VBM. However, the parameters were optimized for each technique.

The results suggest a strong link between structure and motor function that has not yet been demonstrated in a comparable cohort in HD. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that these correlations may reflect a common association with overall HD progression rather than a direct functional association. We are aware that etiologic conclusions may only be derived from functional imaging techniques.32 The use of fMRI in multicenter studies remains a challenge for future developments, however, the literature provides us with ample evidence for an overlap between affected brain regions and tapping tasks.

Several brain regions predominantly affected in HD play an important role in internal time-keeping processes. Timing processes in self-paced tapping involve the SMA,33 premotor cortex,33,34 dorsolateral prefrontal cortex,35 and basal ganglia.36,37 Functional compensation mechanisms have been postulated in premanifest HD.38,39

White matter changes were suggested to represent the earliest measurable changes in HD and precede cell death.3 Information processing speed assessed by intraindividual variability in a reaction time task was associated with decreased white matter volume.40 As a repetitive task, speeded tapping requires rapid execution of extension-flexion movements and thus rapid cerebral processing. Accordingly, we found speeded tapping measures to distinguish better between preHD-A and controls. Additionally, IOI (speeded tapping) correlated more strongly with internal capsule volume than ΔIOI (metronome tapping). Thus initial changes may be partially due to processes underlying movement preparation and execution, possibly white matter changes. Speeded tapping may therefore be of particular interest in the assessment of earliest changes. In contrast, the speeded tapping frequency showed the greatest contrast between preHD-B and HD1, and may serve as disease onset marker.

TD shows a distinct character with higher effect sizes in between-group and subgroup comparisons in speeded tapping; TD best distinguishes between preHD-A and controls among the metronome tapping variables. Interestingly, TD (speeded tapping) shows markedly stronger cortical thickness correlations than the other investigated variables; its specific distribution may thus be due to a stronger impact of cortical pathology.

In this cross-sectional study, force-transducer-based speeded and metronome tapping tasks provided sensitive, objective measures of motor dysfunction. Motor deficits in premanifest and premotor HD gene carriers were measurable in a subgroup of gene carriers with a median of 14 years (preHD-A) before estimated disease onset; earliest changes seem to be more sensitively detectable in speeded tapping, whereas some later stages of disease are more reliably distinguished by the metronome task. Tapping interval variability was the most robust quantitative motor measure and correlated with disease genotype and phenotype as well as structural changes within the brain. Although evidence for pathophysiologic changes underlying tapping impairment in HD is ample, distinct processes are diverse and remain speculative. Tapping devices are portable and can be easily applied in an outpatient setting by trained technicians. They may increase the sensitivity and reliability of motor measurements in clinical trials and supplement or even ultimately substitute categorical rating scales. Their sensitivity in detecting disease progression will be investigated prospectively in the TRACK-HD study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Statistical analysis was conducted by T. Acharya and Dr. D.R. Langbehn.

COINVESTIGATORS

Allison Coleman (UBC, Vancouver, BC, Canada; local site investigator); Joji Decolongon (UBC, Vancouver, BC, Canada; local site investigator); Eve Dumas (Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands; local site investigator); Damian Justo (Groupe Hospitalier Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France; local site investigator); Nayana Lahiri (UCL, London, Great Britain; local site investigator); Cecilia Marelli (Groupe Hospitalier Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France; local site investigator); Joy Read (UCL, London, Great Britain; local site investigator); Rachelle Dar Santos (UBC, Vancouver, BC, Canada; local site investigator); Caroline Jurgens (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands; local site investigator); Marie-Noelle Witjes-Ane (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, the Netherlands; local site investigator); Gail Owen (UCL, London, Great Britain; central study coordination); Saiqah Munir (UCL, London, Great Britain; central study coordination); Azra Hassanali (UCL, London, Great Britain; central study coordination).

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the TRACK-HD study participants; the CHDI/HighQ Foundation, a non-for-profit organization dedicated to finding treatments for HD, for providing financial support (www.highqfoundation.org); and the following individuals for their contributions: Beth Borowsky (CHDI/HighQ Foundation; director, translational medicine); Allan J Tobin (CHDI/HighQ Foundation; senior scientific advisor); Ethan Signer (CHDI/HighQ Foundation; senior scientific advisor); Daniel van Kammen (CHDI/HighQ Foundation; chief medical officer); Robi Blumenstein (CHDI/HighQ Foundation; president); Sherry Lifer (CHDI/HighQ Foundation; project manager); Theresia Kelm (University of Ulm, Germany; central monitoring); Felix Mudoh Tita (University of Ulm, Germany; central monitoring); Irina Vainer (University of Ulm, Germany; central monitoring); Katja Vitkin (University of Ulm, Germany; central monitoring); Thorsten Illmann (2mt Software GmbH, Ulm, Germany; maintenance of the study server); Jürgen Naegler-Ihlein (2mt Software GmbH, Ulm, Germany; maintenance of the study server); Nicole Piller (2mt Software GmbH, Ulm, Germany; maintenance of the study server); Michael Wallner (2mt Software GmbH, Ulm, Germany; maintenance of the study server); Josef Boes (University of Münster, Germany; construction of the quantitative motor equipment); Axel Zscheile (University of Münster, Germany; construction of the quantitative motor equipment); Jens Sommer (University of Muenster, Germany; local IT support); Rudolf Reiz (University of Muenster, Germany; local IT support); Stefanie Mannsfeld (University of Muenster, Germany; assistance with project management); Heike Beckmann (University of Muenster, Germany; assistance with project management); Barbara Edge (University of Muenster, Germany; assistance with project management); Anders Backstoem (University of Umeå, Sweden; assistance with programming of WINSC/WINZOOM routines); Roland Johansson (University of Umeå, Sweden; assistance with programming of WINSC/WINZOOM routines); Rebecca Jones (UCL, London, Great Britain; statistical assistance); Chris Frost (UCL, London, Great Britain; statistical assistance); Arthur Toga (Laboratory of Neuro Imaging UCLA) (LONI), Los Angeles, CA; David Cash (IXICO, London, Great Britain; centralized MRI quality control and data storage); Chris Foley (IXICO, London, Great Britain; centralized MRI quality control and data storage); Nameeta Lobo (IXICO, London, Great Britain; centralized MRI quality control and data storage); James Mackintosh (IXICO, London, Great Britain; centralized MRI quality control and data storage); Kate McLeish (IXICO, London, Great Britain; centralized MRI quality control and data storage); Deborah White (IXICO, London, Great Britain; centralized MRI quality control and data storage); Ray Young (UCL, London, Great Britain; editorial assistance with VBM images); Biorep Technologies, Milan, Italy (determining CAG repeat length); and all TRACK-HD investigators who have not been mentioned individually for their efforts in conducting this study (www.track-hd.net).

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Bechtel receives research support from the CHDI/HighQ Foundation, Inc. Dr. Scahill receives research support from the CHDI/HighQ Foundation, Inc. Dr. Rosas receives research support from the NIH (NINDS P01 NS058793 [Co-PI] and NIH NINDS R01 NS042861 [PI]) and the CHDI/HighQ Foundation, Inc. T. Acharya, Dr. van den Bogaard, C. Jauffret, M.J. Say, Dr. Sturrock, Dr. Johnson, Dr. Onorato, Dr. Salat, Dr. Durr, Dr. Leavitt, and Dr. Roos report no disclosures. Dr. Landwehrmeyer serves on scientific advisory boards for Trophos and Siena Biotech S.p.A.; has received funding for travel from Temmler Pharma GmbH & Co. KG; receives royalties from the publication of Juvenile Huntington's Disease (Oxford University Press, 2009); and receives research support from Novartis, Medivation, Inc., Horizon Pharma, Inc., NeuroSearch, Amarin Corporation, and CHDI Foundation, Inc. Dr. Langbehn receives/has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, the NIH (NIDA R01 DAO5821 [biostatistician, coinvestigator], NINDS 1R01 NS40068-1 [biostatistician, coinvestigator], NINDS R01 NS054893-01A1 [biostatistician], and NIH RO1 NG HG003330-01A1 [biostatistician]), CHDI Foundation, Inc., and from the Michael J. Fox Foundation. Dr. Stout has served as a consultant for and received funding for travel from Medivation, Inc.; serves on the editorial advisory boards of the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society and Brain Imaging and Behavior; and receives research support from the NIH (NINDS NS40068 [coinvestigator]), and CHDI Foundation, Inc. Prof. Tabrizi receives research support from the CHDI, Wellcome Trust, and MRC. Dr. Reilmann serves on scientific advisory boards for Wyeth, the CHDI, Novartis, Siena Biotech S.p.A., and Neurosearch; holds a patent re: Glossomotography; received speaker honoraria from Temmler Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Neurosearch and the Huntington Study Group; and receives research support from the European Huntington's Disease Network and the CHDI/HighQ Foundation, Inc.

Supplementary Material

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Ralf Reilmann, EHDN Huntington Center Münster, Department of Neurology, University Clinic Münster (UKM), University of Münster, Albert-Schweitzer-Strasse 33, 48129 Münster, Germany r.reilmann@uni-muenster.de

Editorial, page 2142

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

e-Pub ahead of print on November 10, 2010, at www.neurology.org.

Study funding: Supported by the CHDI/HighQ Foundation, a non-for-profit organization dedicated to finding treatments for HD. The cortical thickness imaging work was additionally supported by NIH P01NS058793 and R01NS042861.

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

Received February 24, 2010. Accepted in final form July 1, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aylward EH, Brandt J, Codori AM, Mangus RS, Barta PE, Harris GJ. Reduced basal ganglia volume associated with the gene for Huntington's disease in asymptomatic at-risk persons. Neurology 1994;44:823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosas HD, Salat DH, Lee SY, et al. Cerebral cortex and the clinical expression of Huntington's disease: complexity and heterogeneity. Brain 2008;131:1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reading SA, Yassa MA, Bakker A, et al. Regional white matter change in pre-symptomatic Huntington's disease: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res 2005;140:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosas HD, Tuch DS, Hevelone ND, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging in presymptomatic and early Huntington's disease: Selective white matter pathology and its relationship to clinical measures. Mov Disord 2006;21:1317–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marder K, Zhao H, Myers RH, et al. Rate of functional decline in Huntington's disease: Huntington Study Group. Neurology 2000;54:452–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulsen JS, Langbehn DR, Stout JC, et al. Detection of Huntington's disease decades before diagnosis: the Predict-HD study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:874–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabrizi SJ, Langbehn DR, Leavitt BR, et al. Biological and clinical manifestations of Huntington's disease in the longitudinal TRACK-HD study: cross-sectional analysis of baseline data. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:791–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkwood SC, Siemers E, Stout JC, et al. Longitudinal cognitive and motor changes among presymptomatic Huntington disease gene carriers. Arch Neurol 1999;56:563–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MA, Brandt J, Shadmehr R. Motor disorder in Huntington's disease begins as a dysfunction in error feedback control. Nature 2000;403:544–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrich J, Saft C, Ostholt N, Muller T. Assessment of simple movements and progression of Huntington's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007;78:405–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penney JB Jr, Vonsattel JP, MacDonald ME, Gusella JF, Myers RH. CAG repeat number governs the development rate of pathology in Huntington's disease. Ann Neurol 1997;41:689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Langbehn DR, Brinkman RR, Falush D, Paulsen JS, Hayden MR. A new model for prediction of the age of onset and penetrance for Huntington's disease based on CAG length. Clin Genet 2004;65:267–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoulson I, Fahn S. Huntington disease: clinical care and evaluation. Neurology 1979;29:1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971;9:97–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solodkin A, Hlustik P, Noll DC, Small SL. Lateralization of motor circuits and handedness during finger movements. Eur J Neurol 2001;8:425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langbehn DR, Hayden MR, Paulsen JS. CAG-repeat length and the age of onset in Huntington disease (HD): a review and validation study of statistical approaches. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2010;153B:397–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridgway GR, Omar R, Ourselin S, Hill DL, Warren JD, Fox NC. Issues with threshold masking in voxel-based morphometry of atrophied brains. Neuroimage 2009;44:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saft C, Andrich J, Meisel NM, Przuntek H, Muller T. Assessment of simple movements reflects impairment in Huntington's disease. Mov Disord 2006;21:1208–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michell AW, Goodman AO, Silva AH, Lazic SE, Morton AJ, Barker RA. Hand tapping: a simple, reproducible, objective marker of motor dysfunction in Huntington's disease. J Neurol 2008;255:1145–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Boo G, Tibben A, Hermans J, Maat A, Roos RA. Subtle involuntary movements are not reliable indicators of incipient Huntington's disease. Mov Disord 1998;13:96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hogarth P, Kayson E, Kieburtz K, et al. Interrater agreement in the assessment of motor manifestations of Huntington's disease. Mov Disord 2005;20:293–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huntington Study Group. Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale: reliability and consistency. Mov Disord 1996;11:136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biglan KM, Ross CA, Langbehn DR, et al. Motor abnormalities in premanifest persons with Huntington's disease: the PREDICT-HD study. Mov Disord 2009;24:1763–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon AM, Quinn L, Reilmann R, Marder K. Coordination of prehensile forces during precision grip in Huntington's disease. Exp Neurol 2000;163:136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reilmann R, Kirsten F, Quinn L, Henningsen H, Marder K, Gordon AM. Objective assessment of progression in Huntington's disease: a 3-year follow-up study. Neurology 2001;57:920–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao AK, Muratori L, Louis ED, Moskowitz CB, Marder KS. Spectrum of gait impairments in presymptomatic and symptomatic Huntington's disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:1100–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman JS, Cody FW, O'Boyle DJ, Craufurd D, Neary D, Snowden JS. Abnormalities of motor timing in Huntington's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 1996;2:81–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinton SC, Paulsen JS, Hoffmann RG, Reynolds NC, Zimbelman JL, Rao SM. Motor timing variability increases in preclinical Huntington's disease patients as estimated onset of motor symptoms approaches. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2007;13:539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hefter H, Homberg V, Lange HW, Freund HJ. Impairment of rapid movement in Huntington's disease. Brain 1987;110:585–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beste C, Saft C, Andrich J, Muller T, Gold R, Falkenstein M. Time processing in Huntington's disease: a group-control study. PLoS One 2007;2:e1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolf RC, Vasic N, Schonfeldt-Lecuona C, Ecker D, Landwehrmeyer GB. Cortical dysfunction in patients with Huntington's disease during working memory performance. Hum Brain Mapp 2009;30:327–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paulsen JS. Functional imaging in Huntington's disease. Exp Neurol 2009;216:272–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartenstein P, Weindl A, Spiegel S, et al. Central motor processing in Huntington's disease: a PET study. Brain 1997;120:1553–1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colebatch JG, Deiber MP, Passingham RE, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RSJ. Regional cerebral blood flow during voluntary arm and hand movements in human subjects. J Neurophysiol 1991;65:1392–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jahanshahi M, Jenkins IH, Brown RG, Marsden CD, Passingham RE, Brooks DJ. Self-initiated versus externally triggered movements: I: an investigation using measurement of regional cerebral blood flow with PET and movement-related potentials in normal and Parkinson's disease subjects. Brain 1995;118:913–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buhusi CV, Meck WH. What makes us tick? Functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005;6:755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kassubek J, Juengling FD, Ecker D, Landwehrmeyer GB. Thalamic atrophy in Huntington's disease co-varies with cognitive performance: a morphometric MRI analysis. Cereb Cortex 2005;15:846–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kloppel S, Draganski B, Siebner HR, Tabrizi SJ, Weiller C, Frackowiak RS. Functional compensation of motor function in pre-symptomatic Huntington's disease. Brain 2009;132:1624–1632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulsen JS, Zimbelman JL, Hinton SC, et al. fMRI biomarker of early neuronal dysfunction in presymptomatic Huntington's disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2004;25:1715–1721. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walhovd KB, Fjell AM. White matter volume predicts reaction time instability. Neuropsychologia 2007;45:2277–2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.