Abstract

Background:

We sought to describe the antemortem clinical and neuroimaging features among patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions (FTLD-TDP).

Methods:

Subjects were recruited from a consecutive series of patients with a primary neuropathologic diagnosis of FTLD-TDP and antemortem MRI. Twenty-eight patients met entry criteria: 9 with type 1, 5 with type 2, and 10 with type 3 FTLD-TDP. Four patients had too sparse FTLD-TDP pathology to be subtyped. Clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging features of these cases were reviewed. Voxel-based morphometry was used to assess regional gray matter atrophy in relation to a group of 50 cognitively normal control subjects.

Results:

Clinical diagnosis varied between the groups: semantic dementia was only associated with type 1 pathology, whereas progressive nonfluent aphasia and corticobasal syndrome were only associated with type 3. Behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia and frontotemporal dementia with motor neuron disease were seen in type 2 or type 3 pathology. The neuroimaging analysis revealed distinct patterns of atrophy between the pathologic subtypes: type 1 was associated with asymmetric anterior temporal lobe atrophy (either left- or right-predominant) with involvement also of the orbitofrontal lobes and insulae; type 2 with relatively symmetric atrophy of the medial temporal, medial prefrontal, and orbitofrontal-insular cortices; and type 3 with asymmetric atrophy (either left- or right-predominant) involving more dorsal areas including frontal, temporal, and inferior parietal cortices as well as striatum and thalamus. No significant atrophy was seen among patients with too sparse pathology to be subtyped.

Conclusions:

FTLD-TDP subtypes have distinct clinical and neuroimaging features, highlighting the relevance of FTLD-TDP subtyping to clinicopathologic correlation.

GLOSSARY

- bvFTD

= behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia;

- CBS

= corticobasal syndrome;

- CDR

= Clinical Dementia Rating;

- FDR

= false discovery rate;

- FTD

= frontotemporal dementia;

- FTLD

= frontotemporal lobar degeneration;

- FTLD-TDP

= frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 immunoreactive inclusions;

- FUS

= fused in sarcoma;

- MMSE

= Mini-Mental State Examination;

- MND

= motor neuron disease;

- PNFA

= progressive nonfluent aphasia;

- TDP-43

= TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa;

- UCSF

= University of California, San Francisco;

- VBM

= voxel-based morphometry.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) is a genetically and pathologically heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder presenting with either behavioral or language impairment.1 Studies have demonstrated 3 major FTLD molecular classes, characterized by abnormal cellular inclusions containing either tau, TAR DNA-binding protein of 43 kDa (TDP-43), or fused in sarcoma (FUS) protein,1 with TDP-43 pathology being the most common.2 FTLD with tau-immunoreactive inclusions (FTLD-tau) has long been associated with diverse pathologic subtypes, including Pick disease, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and others, all defined by recognizable neuronal and glial pathomorphologies.1,3 Recent work has demonstrated a similar diversity within the FTLD-TDP spectrum with 4 subtypes currently recognized.4–7

Correlations have begun to emerge between frontotemporal dementia (FTD) clinical syndromes and underlying TDP-43 subtypes.2,8–10 In this study, we grouped a consecutive series of patients with FTLD-TDP according to pathologic subtype and examined the associated antemortem clinical, neuropsychological, and neuroimaging features. We hypothesized that 1) type 1 would be associated with semantic dementia, including patients with both left- and right-predominant temporal polar disease, and would show corresponding asymmetric atrophy within a temporal pole network for semantic and emotional meaning, 2) type 2 would be predominantly associated with behavioral variant FTD (bvFTD), with or without motor neuron disease (MND), and would show frontoinsular and medial frontal atrophy, and 3) type 3 would include most patients with PNFA or CBS and feature more dorsal frontoparietal and dorsal insular atrophy.

METHODS

Subjects.

Subjects were recruited from a consecutive series of patients attending the Memory and Aging Center at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) with a primary neuropathologic diagnosis of FTLD-TDP and an antemortem volumetric MRI brain scan performed on a 1.5-T magnetic resonance scanner. Because comorbid Alzheimer disease–related and Lewy body pathologies are common in older subjects, the presence of one or more of these comorbidities did not constitute an exclusion criterion. A control group of 50 age- and gender-matched cognitively normal subjects was also included: 28 male subjects, mean age at scan of 61.4 years (SD = 7.8).

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from UCSF Committee on Human Research. Written research consent was obtained from all patients prior to study participation.

Clinical and neuropsychological assessment.

All patients underwent a standard clinical assessment including Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE, 11) and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR, 12). Neuropsychometry was also performed including assessment of naming (Abbreviated Boston Naming Test, 13), verbal memory (California Verbal Learning Test–short form, 14), visuospatial skills and visual memory (modified Rey Figure, copy and delay score, 15), and executive function (Trail Making Test, 16 and Design Fluency, 17, as well as verbal fluency and backwards digit span). The groups were compared statistically using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc pairwise analysis (STATA10©, Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Brain imaging.

Structural MRI was performed with a 1.5-T Magneton VISION system (Siemens Inc., Iselin, NJ). A volumetric magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo MRI (repetition time, 10 msec; echo time, 4 msec; inversion time, 300 msec) was used to obtain a T1-weighted image of the entire brain (15° flip angle, coronal orientation perpendicular to the double spin echo sequence, 1.0 × 1.0 mm2 in-plane resolution of 1.5-mm slab thickness).

Initially, cortical and subcortical volumes were generated using the Freesurfer analysis suite (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/). This allowed a left/right asymmetry ratio to be calculated by dividing the total left hemisphere volumes by the right hemisphere volumes to provide a measure of how asymmetric the atrophy was in each patient. Voxel-based morphometry (VBM) was performed using SPM5 software (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm) and the DARTEL toolbox with default settings for all parameters.18 Voxel gray matter intensity, V, was modeled as a function of group, and subject age, gender, and total intracranial volume (calculated within SPM5) were included as nuisance covariates. Maps showing significant differences between the groups were generated, correcting for multiple comparisons by thresholding the images of t statistics to control the false discovery rate (FDR) at a 0.001 significance level. Statistical parametric maps were displayed as overlays on a study-specific template, created by warping all native space whole-brain images to the final DARTEL template and calculating the average of the warped brain images.

Neuropathologic assessment.

All patients underwent a comprehensive neuropathologic assessment as previously described.19,20 Briefly, fixation protocols varied depending on the site and date of autopsy. Although all patients were clinically evaluated at UCSF, autopsies were divided between UCSF and the University of Pennsylvania. For all brains autopsied at the University of Pennsylvania and some autopsied at UCSF, whole hemispheres were immersion fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for at least 1 week. Additional brains autopsied at UCSF were freshly cut into 8- to 10-mm-thick whole-brain coronal slabs. These slabs were alternately fixed, in freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde for 72 hours, or rapidly frozen. Tissue blocks covering neocortical, limbic, subcortical, and brainstem regions were dissected following consensus guidelines for the standardized assessment of dementia neuropathology,21 and basic and immunohistochemical stains were applied. Immunohistochemistry was performed using antibodies to ubiquitin (antirabbit, 1:1,000, DAKO North America, Carpinteria, CA), TDP43 (antirabbit, 1:2,000, Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL), hyperphosphorylated tau (CP-13 antibody, courtesy of P. Davies), β-amyloid (antimouse, 1:250, Millipore, Billerica, MA), glial fibrillary acidic protein (antirabbit, 1:250, DAKO North America), α-synuclein (antimouse, 1:1,000, Millipore), α-internexin (antimouse, 1:200, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and FUS (antirabbit, 1:200, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). All immunohistochemical runs included positive control sections to exclude technical factors as a cause of absent immunoreactivity.

Further pathologic subtyping of the patients with FTLD-TDP was performed. Two closely related nomenclatures have been put forward for FTLD-TDP subtyping4,5: type 1 Sampathu (type 2 Mackenzie) is associated with long, TDP-43 immunoreactive, dystrophic neurites but few neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions; type 2 Sampathu (type 3 Mackenzie) is associated with predominantly granular or stippled neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions in superficial and deep layers; and type 3 Sampathu (type 1 Mackenzie) is associated with crescentic or compact neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, abundant short angulated neuropil threads, and, more variably, neuronal intranuclear inclusions.6,7 Patients with null mutations in progranulin who have come to autopsy have shown Sampathu type 3 FTLD-TDP.22 A fourth rare subtype associated with mutations in the valosin-containing protein gene has also been described.6 For clarity, the Sampathu scheme is applied throughout the remainder of the article.

RESULTS

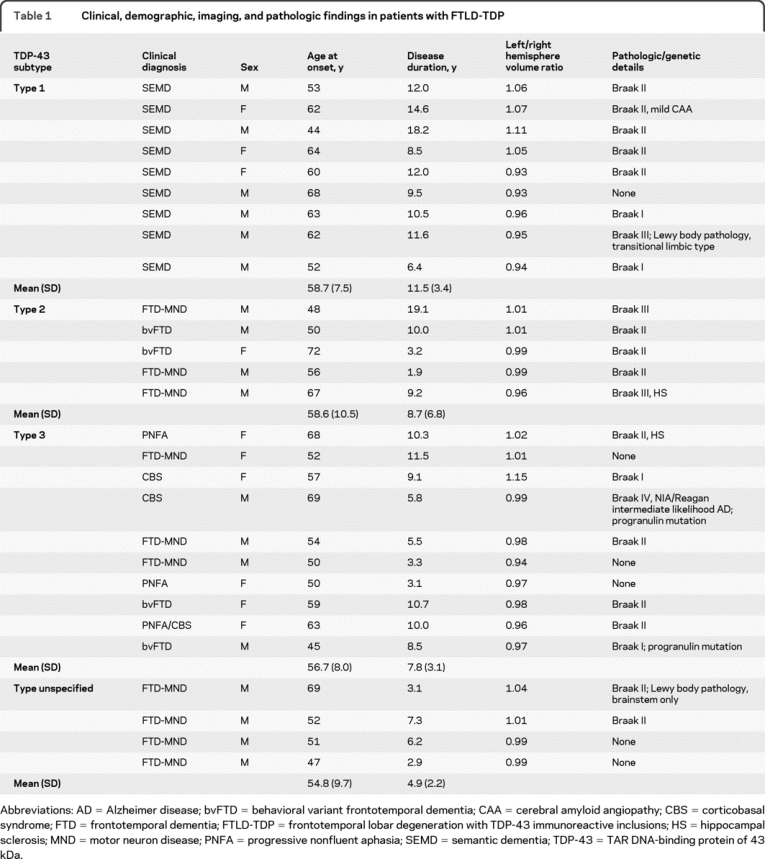

Twenty-eight patients met entry criteria and were included in the study (18 men, 10 women) with a mean age at scan of 62.4 years (SD = 7.9). Nine patients had type 1 pathology, 5 had type 2, 10 had type 3 (including 2 with known progranulin mutations), and 4 had FTLD-TDP pathology that proved too sparse to be subtyped (table 1). In the unclassifiable group, TDP-43 pathology took the form of rare compact, granular, crescentic, or skein-like neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, glial cytoplasmic inclusions, or short dystrophic neurites in superficial or deep layers, with some variation between cases. Anterior cingulate cortex and dentate gyrus granule cells were consistently sampled and showed scarce TDP-43 pathology in all unclassifiable patients, although other frontal and temporal regions showed some pathology in selected patients.

Table 1 Clinical, demographic, imaging, and pathologic findings in patients with FTLD-TDP

Clinical diagnosis varied between the groups, with semantic dementia seen only in FTLD-TDP type 1, with no other clinical diagnosis made in patients with this pathology. Although patients with both left- and right-predominant bitemporal atrophy all had semantic impairment characteristic of semantic dementia, behavioral symptoms were more conspicuous in the right-predominant patients and were often the first manifestations. These patients were clinically classified as semantic dementia due to the profound semantic impairment at presentation, although they may have been classified as bvFTD at some centers if seen earlier in the disease course. Progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA) and corticobasal syndrome (CBS) were only seen in type 3 pathology, although both bvFTD and FTD-MND were seen in type 2 and type 3. All 4 patients in whom the FTLD-TDP could not be subtyped had clinical FTD-MND (table 1). Age at onset and disease duration overlapped between the subgroups although there was longer duration in the type 1 subtype compared to type 3 (p = 0.02) and a trend toward longer duration compared to type 2 (tables 1 and 2). All groups contained patients with asymmetric atrophy although type 1 was the most asymmetric (4 patients with greater right hemisphere atrophy and 5 with greater left hemisphere involvement): mean hemispheric volume difference was 37.3 (10.9) mL in type 1, compared to 19.8 (17.7) in type 3 and only 7.1 (6.8) in type 2, in which most patients showed relatively symmetric atrophy (table 1).

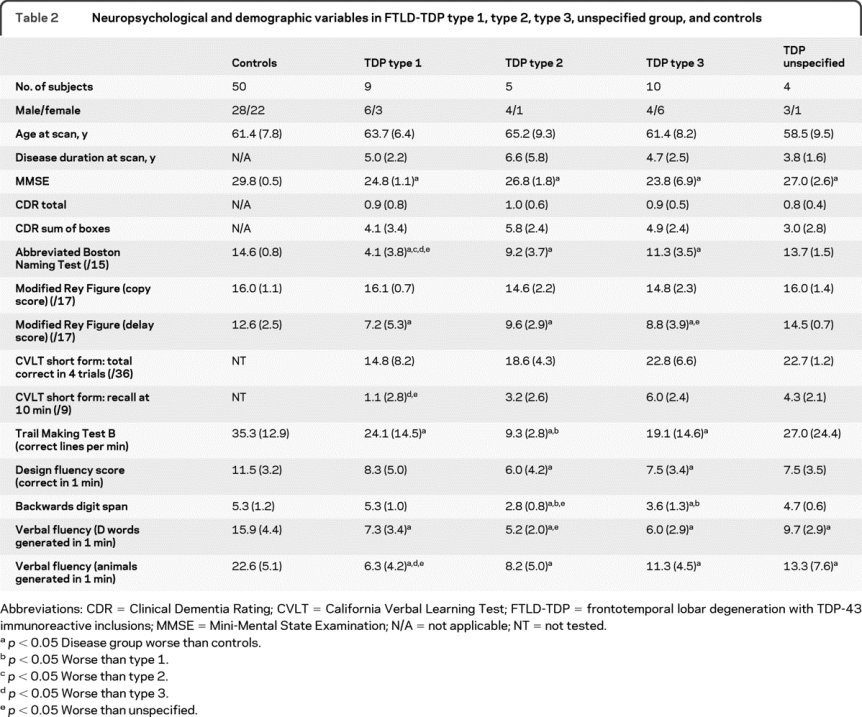

Table 2 Neuropsychological and demographic variables in FTLD-TDP type 1, type 2, type 3, unspecified group, and controls

Neuropsychological assessment was consistent with clinical diagnosis (table 2). Naming was most affected in type 1 (semantic dementia) and worse than in the other groups (vs type 2 p = 0.03, vs type 3 p = 0.01, vs unspecified p = 0.02), with worse performance in those showing left-predominant atrophy compared to the right-sided group (table e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org). Verbal memory scores were also worse in the type 1 group compared with type 3 (California Verbal Learning Test recall at 10 minutes, p = 0.009) and the unspecified group (p = 0.045) with a trend toward worse performance compared to type 2 (p = 0.08). In the type 1 group, performance on verbal memory tests was worse in the left-sided group compared to right, whereas performance on visual memory tests was worse in the right-sided group (table e-1). Executive function was worst in the type 2 patients with poorer performance on the Trail Making Test than type 1 (p = 0.04) and a trend to worse performance than type 3 (p = 0.09).

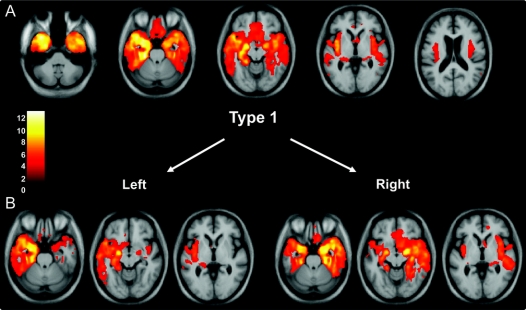

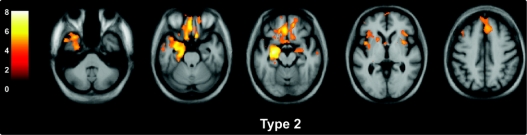

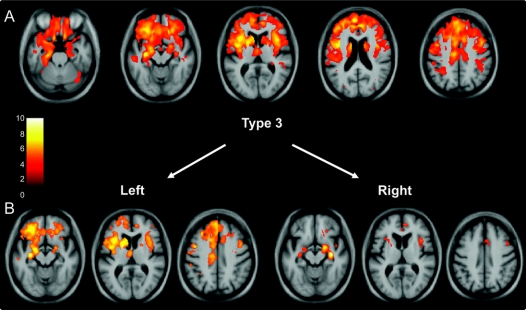

VBM analysis was performed in both the total TDP groups and also in subgroups defined by left- or right-predominant atrophy. Type 1 was associated with atrophy in the temporal lobes (especially in polar and anterior regions), the amygdalae, hippocampi, orbitofrontal lobes, and insulae (figure 1). Subgrouping the patients by side of worst atrophy highlighted the asymmetric nature of the illness, which can be either left- or right-predominant with a mirror-image pattern seen in the 2 groups (figure 1). Significant atrophy in type 2 was identified in medial and polar temporal lobes, especially on the left, as well as anterior cingulate, anterior insulae, medial prefrontal, and orbitofrontal cortices. Although the pattern was relatively symmetric outside of the temporal lobe, one patient in this group showed left-predominant atrophy (table 1), which most likely drove the asymmetric temporal atrophy effect shown in figure 2. Splitting the type 2 group by side of worst atrophy left only small groups for analysis, and only the left-sided group showed significantly atrophied regions, mostly asymmetric (left greater than right) medial temporal lobe. In type 3, the atrophy showed a more dorsal pattern, including the inferior, middle, and superior frontal gyri, anterior, medial, and posterior temporal regions, amygdalae, insulae, anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal cortex, inferior parietal lobes, striatum, and thalamus (figure 3). Similar mirror-image patterns were seen in the subgroups with right- and left-sided predominant atrophy, although the extent of atrophy in each group varied, most likely due to differences in sample size. The unspecified TDP group did not show areas of significant atrophy at the predetermined statistical significance threshold.

Figure 1 Voxel-based morphometry analysis on gray matter regions in the type 1 group relative to healthy controls (A) and in the type 1 subgroups with left- and right-sided predominant atrophy (B)

Statistical parametric maps have been thresholded at p < 0.001 after false discovery rate correction over the whole brain volume and rendered on a study-specific average group T1-weighted MRI template image in DARTEL space. The color bar (left) indicates the t score. The left hemisphere is shown on the left of each figure.

Figure 2 Voxel-based morphometry analysis on gray matter regions in the type 2 group relative to healthy controls

Statistical parametric maps have been thresholded at p < 0.001 after false discovery rate correction over the whole brain volume and rendered on a study-specific average group T1-weighted MRI template image in DARTEL space. The color bar (left) indicates the t score. The left hemisphere is shown on the left of each figure.

Figure 3 Voxel-based morphometry analysis on gray matter regions in the type 3 group relative to healthy controls (A) and in the type 3 subgroups with right- and left-sided predominant atrophy (B)

Statistical parametric maps have been thresholded at p < 0.001 after false discovery rate correction over the whole brain volume and rendered on a study-specific average group T1-weighted MRI template image in DARTEL space. The color bar (left) indicates the t score. The left hemisphere is shown on the left of each figure.

DISCUSSION

Consistent with previous studies,5–9 this study shows that different FTD clinical syndromes and patterns of neuropsychological impairment are seen in each FTLD-TDP subtype. Following from these observations, this study links each TDP-43 subtype to distinct cerebral atrophy patterns. Type 1 FTLD-TDP is associated with semantic dementia and with either left or right-predominant anterior temporal lobe atrophy. Type 2 is associated with bvFTD or FTD-MND and a more symmetric pattern involving the anteromedial temporal and orbitomedial frontal lobes and anterior insulae. Type 3 is associated with PNFA and corticobasal syndrome, as well as with bvFTD and FTD-MND. Accordingly, we identified a more dorsal pattern of asymmetric atrophy affecting the frontal, temporal, and insular lobes as well as the anterior cingulate and parietal areas. The unclassifiable patients all presented with FTD-MND, but no significant areas of atrophy were detected. The present clinical and anatomic associations argue that TDP-43 subtyping provides a biologically significant framework for understanding the FTLD-TDP spectrum.

Previous pathologic FTLD series have investigated the clinical features associated with TDP-43 pathology although without subtype-specific imaging analysis.2,9,23–29 Findings in this study consistent with previous work are the association of semantic dementia with type 12 and the association of PNFA and CBS with type 3, including patients with progranulin mutations.10,24 FTD-MND has been associated most closely with Type 2 pathology2 but also in some series with type 323,25 (as in this study). The percentage of cases with FTD-MND and type 3 FTLD-TDP varies widely between series, with some reporting no cases29 and one reporting MND in almost half of the patients with type 3 pathology.25

A recent study suggested, based on a principle component analysis of reduced neuropathologic data, that TDP-43 pathology forms a continuum rather than distinct subtypes.30 Our findings, in contrast, provide novel neuroimaging evidence to support TDP-43 subtyping as a biologically meaningful and constructive framework for understanding FTLD-TDP. Four patients who could not be categorized according to current schemes had MND and died with TDP-43 pathology too sparse to classify. Consistent with a short disease duration and better performance on neuropsychological testing, these patients showed no significant atrophy in the VBM analysis, and the brains of these patients showed little cerebral gross atrophy at postmortem.

Finally, this study demonstrates the atrophy pattern seen in semantic dementia due to a single underlying pathology. Previous studies suggest that type 1 FTLD-TDP is by far the most common pathologic substrate for this syndrome,31 but some patients with FTLD-tau or Alzheimer disease also present with semantic dementia and may show a different anatomic pattern.32 This heterogeneity could have altered prior imaging findings based on living patients with mixed pathologic substrates. Here, patients with type 1 FTLD-TDP and semantic dementia featuring left- and right-predominant degeneration showed nearly mirror-image atrophy patterns, supporting the notion that these 2 clinical syndromes reflect the same underlying disorder.33,34

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in neurodegeneration research.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Rohrer has received research support from the Wellcome Trust (Clinical Research Fellowship) and Brain (Exit Scholarship). Dr. Geser has received research support from the NIH (AG10124 [researcher] and AG17586 [researcher]). Dr. Zhou, Dr. Gennatas, and M. Sidhu report no disclosures. Dr. Trojanowski has received funding for travel and honoraria from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.; has received speaker honoraria from Pfizer Inc.; serves as an Associate Editor of Alzheimer's & Dementia; may accrue revenue on patents re: Modified avidin-biotin technique, Method of stabilizing microtubules to treat Alzheimer's disease, Method of detecting abnormally phosphorylated tau, Method of screening for Alzheimer's disease or disease associated with the accumulation of paired helical filaments, Compositions and methods for producing and using homogeneous neuronal cell transplants, Rat comprising straight filaments in its brain, Compositions and methods for producing and using homogeneous neuronal cell transplants to treat neurodegenerative disorders and brain and spinal cord injuries, Diagnostic methods for Alzheimer's disease by detection of multiple MRNAs, Methods and compositions for determining lipid peroxidation levels in oxidant stress syndromes and diseases, Compositions and methods for producing and using homogenous neuronal cell transplants, Method of identifying, diagnosing and treating α-synuclein positive neurodegenerative disorders, Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome-17: genotype predicts phenotype, microtubule stabilizing therapies for neurodegenerative disorders, and Treatment of Alzheimer's and related diseases with an antibody; and receives research support from the NIH (NIA P01 AG 09215-20 [PI], NIA P30 AG 10124-18 [PI], NIA PO1 AG 17586-10 [Project 4 Leader], NIA 1PO1 AG-19724-07 [Core C Leader], NIA 1 U01 AG 024904-05 [Co-PI Biomarker Core Laboratory], NINDS P50 NS053488-02 [PI], NIA UO1 AG029213-01 [Co-I]; RC2NS069368 [PI], RC1AG035427 [PI], and NIA P30AG036468 [PI]) and the Marian S. Ware Alzheimer Program. Dr. DeArmond has received research support from the NIH (AG023501 [Co-I]). Dr. Miller serves on a scientific advisory board for the Alzheimer's Disease Clinical Study; serves as an Editor for Neurocase and as an Associate Editor of ADAD; receives royalties from the publication of Behavioral Neurology of Dementia (Cambridge, 2009), Handbook of Neurology (Elsevier, 2009), and The Human Frontal Lobes (Guilford, 2008); serves as a consultant for Lundbeck Inc., Elan Corporation, and Allon Therapeutics, Inc.; serves on speakers' bureaus for Novartis and Pfizer Inc.; and receives research support from Novartis and the NIH (NIA P50 AG23501 [PI] and NIA P01 AG19724 [PI]) and the State of California Alzheimer's Center. Dr. Seeley has received research support from the NIH (R01 AG033017 [PI] and P50 AG023501 [coinvestigator]), the James S. McDonnell Foundation, and the Consortium for Frontotemporal Dementia Research.

Supplementary Material

Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. William Seeley, Department of Neurology, University of California, San Francisco, Box 1207, San Francisco, CA 94143-1207 wseeley@memory.ucsf.edu

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

Disclosure: Author disclosures are provided at the end of the article.

Received May 18, 2010. Accepted in final form September 7, 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol 2010;119:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snowden J, Neary D, Mann D. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: clinical and pathological relationships. Acta Neuropathol 2007;114:31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dickson DW. Neuropathologic differentiation of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration. J Neurol 1999;246(suppl 2):II6–II15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sampathu DM, Neumann M, Kwong LK, et al. Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am J Pathol 2006;169:1343–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackenzie IR, Baborie A, Pickering-Brown S, et al. Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol 2006;112:539–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forman MS, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. TDP-43: a novel neurodegenerative proteinopathy. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007;17:548–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geser F, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a spectrum of TDP-43 proteinopathies. Neuropathology Epub 2010 Jan 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Van Deerlin VM, Wood EM, Moore P, et al. Clinical, genetic, and pathologic characteristics of patients with frontotemporal dementia and progranulin mutations. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1148–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman M, Wood EM, Moore P, et al. TDP-43 pathologic lesions and clinical phenotype in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions. Arch Neurol 2007;64:1449–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck J, Rohrer JD, Campbell T, et al. A distinct clinical, neuropsychological and radiological phenotype is associated with progranulin gene mutations in a large UK series. Brain 2008;131:706–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. The “Mini Mental State”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43:2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaplan EF, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. The Boston Naming Test. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delis DC, Kramer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test, 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osterrieth PA. Le test de copie d'une figure complexe: contribution a l'eìtude de la perception et de la me ìmoire. Arch Psychol 1944;30:206–256. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reitan RM. Validity of the Trailmaking Test as an indication of organic brain damage. Percept Mot Skills 1958;8:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delis DC, Kaplan E, Kramer JH. The Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohrer JD, Ridgway GR, Crutch SJ, et al. Progressive logopenic/phonological aphasia: erosion of the language network. Neuroimage 2010;49:984–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tartaglia MC, Sidhu M, Laluz V, et al. Sporadic corticobasal syndrome due to FTLD-TDP. Acta Neuropathol 2010;119:365–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabinovici GD, Seeley WW, Kim EJ, et al. Distinct MRI atrophy patterns in autopsy-proven Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement 2007–2008;22:474–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): part II: standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1991;41:479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie IR, Baker M, Pickering-Brown S, et al. The neuropathology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration caused by mutations in the progranulin gene. Brain 2006;129:3081–3090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cairns NJ, Neumann M, Bigio EH, et al. TDP-43 in familial and sporadic frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin inclusions. Am J Pathol 2007;171:227–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davion S, Johnson N, Weintraub S, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation in PGRN mutations. Neurology 2007;69:1113–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geser F, Martinez-Lage M, Robinson J, et al. Clinical and pathological continuum of multisystem TDP-43 proteinopathies. Arch Neurol 2009;66:180–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr, Baker M, et al. Voxel-based morphometry in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions with and without progranulin mutations. Arch Neurol 2007;64:371–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitwell JL, Jack CR Jr, Senjem ML, et al. MRI correlates of protein deposition and disease severity in postmortem frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurodegener Dis 2009;6:106–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Josephs KA, Ahmed Z, Katsuse O, et al. Neuropathologic features of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions with progranulin gene (PGRN) mutations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2007;66:142–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Josephs KA, Stroh A, Dugger B, Dickson DW. Evaluation of subcortical pathology and clinical correlations in FTLD-U subtypes. Acta Neuropathol 2009;118:349–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong RA, Ellis W, Hamilton RL, et al. Neuropathological heterogeneity in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with TDP-43 proteinopathy: a quantitative study of 94 cases using principal components analysis. J Neural Transm 2010;117:227–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hodges JR, Mitchell J, Dawson K, et al. Semantic dementia: demography, familial factors and survival in a consecutive series of 100 cases. Brain 2010;133:300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira JM, Williams GB, Acosta-Cabronero J, et al. Atrophy patterns in histologic vs clinical groupings of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology 2009;72:1653–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeley WW, Bauer AM, Miller BL, et al. The natural history of temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology 2005;64:1384–1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brambati SM, Rankin KP, Narvid J, et al. Atrophy progression in semantic dementia with asymmetric temporal involvement: a tensor-based morphometry study. Neurobiol Aging 2009;30:103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.