Abstract

Objective

Personality factors moderate self-efficacy enhancing effects of some illness self-management interventions, but their influence on self-rated health is unclear This study examined whether high neuroticism and low conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness (the distressed personality profile) moderated the effects of the homing in on health (HIOH) illness self-management intervention on mental and physical health status.

Design

Analysis of data from 384 subjects completing a randomized controlled trial of HIOH.

Methods

Regression analyses examined effects of NEO-five factor inventory scores on SF-36 mental component summary (MCS-36) and physical component summar (PCS-36) scores (baseline; 2, 4, and 6 weeks; 6 months; 1 year), adjusting for age gender, and study group.

Results

Baseline MCS-36 scores were worse in those with the distressed personality profile relative to others: high neuroticism (13.3 points worse, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 11.0, 15.7) and low conscientiousness (6.6 points worse, 95% CI = 4.1, 9.2), extraversion (10.1 points worse, 95% CI = 7.7, 12.5) and agreeableness (4.2 points worse, 95% CI = 1.6, 6.8). Intervention subjects had better MCS-36 scores at 4 and 6 weeks, and benefits were confined to participants with low conscientiousness (4 weeks – 3.7 points better, 95% CI = 0.2, 71; 6 weeks – 5.0 points better, 95% CI = 1.57, 8.4). There were no intervention or personality effects on PCS-36 scores.

Conclusions

Chronically ill self-management intervention recipients with the distressed personality profile had worse self-rated mental health, and conscientiousness moderated the short-term effects of the intervention on self-rated mental health. Measuring personality may help identify individuals more likely to benefit from self-management interventions.

Interventions to help patients manage health conditions hold promise as cost-effective ways to improve chronic illness outcomes (Improving Chronic Illness Care, 2008; Institute of Medicine, 2001; United Kingdom Department of Health, 2008). Research suggests that the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP), designed to enhance participants' illness management self-efficacy (or confidence to perform behaviours necessary to manage chronic conditions), can improve illness outcomes. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found the programme yields short-term (4–6 months) improvements in self-efficacy and some facets of self-rated health, regardless of specific diagnosis (Dongbo et al., 2003; Griffiths et al., 2005; Kennedy et al., 2007; Lorig, Ritter, Laurent, & Plant, 2006; Lorig et al., 1999; Swerissen et al., 2006).

Despite the wide dissemination of the CDSMP, little is known about moderators of its effects. Identifying effect moderators can improve understanding of who is most likely to benefit from interventions, leading to more efficient delivery (Kraemer, Wilson, Fairburn, & Agras, 2002). The extent to which participant dispositional characteristics might moderate the effects of self-management interventions remains unknown, but the five factor model (FFM) personality factors – agreeableness, conscientiousness, extraversion, neuroticism, and openness – appear to be particularly promising targets of study (Costa & McCrae, 1997; Goldberg, 1993; Marshall, Wortman, Vickers, Kusulas, & Hervig, 1994). The result of over seven decades of research (Goldberg, 1993), the FFM is the dominant personality framework among models focused on longitudinally stabl behavioural and dispositional tendencies (McRae & Costa, 2002). The FFM factors are empirically derived, broad clusters of such tendencies (Table 1). They capture the major axes of psychological and behavioural variation in humans and are associated with an array of important health behaviours and outcomes (Bogg & Roberts, 2004; Chapman, Duberstein, & Lyness, 2007a; Chapman, Lyness, & Duberstein, 2007; Friedman, 2000; Mroczek & Spiro, 2007; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007).

Table 1.

Dispositional tendencies within FFM personality factors

| FEM factor | Dispositional tendencies | Example personality questionnaire items |

|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Cooperative, compassionate | I make people feel at ease I sympathize with others' feelings I take time out for others I am not interested in other people' problems* I am not really interested in others* |

| Conscientiousness | Painstaking, careful, planning, achievement-driven | I am always prepared I am exacting in my work I follow a schedule I get chores done right away I like order |

| Extraversion | Stimulation-seeking, tendency to experience positive emotions, sociable | I feel comfortable around people I start conversations I talk to a lot of different people at parties I am quiet around strangers* I laugh a lot |

| Neuroticism | Tendency to experience negative emotions | I am easily disturbed I change my mood a lot I get irritated easily I get stressed out easily I get upset easily |

| Openness | Explore new ideas and experiences, intellectually curious | I have a vivid imagination I have excellent ideas I spend time reflecting on things I use difficult words I am not interested in abstract ideas* |

Note. Asterisk denotes reverse scored items.

In prior analyses of data from a 1-year RCT of homing in on health (HIOH), a variant of the CDSMP delivered either in subjects' homes or by telephone, it was found that delivering the intervention in participants' homes (but not via telephone) significantly increased illness management self-efficacy, an effect peaking at 6 weeks but attenuating by 1-year follow-up (Jerant, Moore, & Franks, 2009). In other prior analyses from the same RCT, it was demonstrated that the self-efficacy enhancing effects of HIOH were moderated by personality factors, being confined to participants with high neuroticism or low agreeableness, conscientiousness, or extraversion (Franks, Chapman, Duberstein, & Jerant, 2009). Of note, this particular grouping of personality factors, which has been termed the distressed personality profile (Chapman, Duberstein, & Lyness, 2007b), is known to be associated with potentially harmful physiologic responses, including poorer immune functioning (Denollet et al., 2003) and increased cortisol release in response to stress (Habra, Linden, Anderson, & Weinberg, 2003), lower self-ratings of health (Chapman et al., 2007b), and increased cardiovascular risk (Kupper & Denollet, 2007).

The current paper examines whether FFM personality factors moderated the effects of HIOH on the primary outcome of self-rated health, measured using the Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 mental component summary (MCS) and physical component summary (PCS) scores (Ware, Kosinski, et al., 1995). Conducting these analyses also afforded an opportunity to build on scant literature regarding effects of personality factors on MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores. The single prior study examining this issue involved a homogeneous sample of Dutch out-patients with mood and anxiety disorders. The study found a relatively strong association between neuroticism and MCS-36 scores, with much weaker associations between extraversion and openness and MCS-36 scores and agreeableness and PCS-36 scores (van Straten, Cuijpers, van Zuuren, Smits, & Donker, 2007).

Based on the aforementioned results of two prior relevant studies conducted by various study co-authors (Chapman et al., 2007b; Franks et al., 2009), we examined the following hypotheses: (1) higher neuroticism, and lower agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion – in other words, the distressed personality profile – will be associated with lower baseline self-rated mental and physical health; (2) the effects of HIOH on MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores over 1 year will be limited to participants with the distressed personality profile.

Methods

Study setting, sample recruitment, and randomization

The study was conducted from July 2004 to December 2007. The University of California Davis Institutional Review Board provided ethical approval of the study and protocol. Power calculations were based on a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of three points in SF-36 physical component summary (PCS-36) and mental component summary (MCS-36) scores (Samsa et al., 1999). A two-point MCID was conservatively employed in calculations, approximating an intervention effect size of 0.2 (small effect; Cohen, 1992). Accounting for possible attrition up to 10%, with alpha 0.05, 120 subjects per group were estimated to provide 80% power to detect a two-point difference in scores.

Study subjects were recruited from the 12 offices in a university-affiliated primary care network in Northern California. Billing code information was used to identify patients aged 40 or older with one or more of the following chronic illnesses: arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, depression, and/or diabetes mellitus. Mass mailed study announcements and telephone calls were employed to recruit patients who met these criteria.

The study coordinator used a standard script to screen interested patients for further eligibility criteria: ability to speak and read English; residence in a private home with an active telephone; adequate eyesight and hearing to participate via telephone and read study materials; and at least one basic activity impairment, as assessed by the health assessment questionnaire (Fries, Spitz, Kraines, & Holman, 1980), and/or a score of four points or greater, suggestive of clinically significant depressive symptoms, on the 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Irwin, Artin, & Oxman, 1999). The latter were based on focus groups (Jerant, von Friederichs-Fitzwater, & Moore, 2005) and discussions with content area experts, which indicated such individuals might be more likely to participate in HIOH than in the original programme.

A study worker visited eligible individuals in their homes to obtain informed consent, administer the baseline study questionnaire (see Measures), and implement randomized allocation in blocks of 12 subjects via sealed opaque envelopes containing slips of paper printed with group assignments.

Procedures

Study intervention

The study intervention, HIOH, and the CDSMP from which it was derived, have been described in detail previously (Jerant et al., 2009; Lorig & Holman, 2003; Lorig et al. 1999; Stanford Patient Education Research Center, 2008). Briefly, HIOH was a one-to-one variant of the group format CDSMP, developed to make the programme content available to individuals less able or willing to participate in group training. HIOH was delivered over six weekly sessions, with content nearly identical to the CDSMP but provided by a single peer one-to-one either in the participant's home or via telephone. The overall aim was mastery of fundamental self-management tasks, with frequent opportunities provided to practice and receive feedback on performance. Specific topics include exercising safely, coping with difficult emotions, and using cognitive symptom management techniques. Four peers underwent week-long training to deliver HIOH. Each provided all six intervention sessions to each of their assigned participants. The same intervention script was employed for both intervention groups. Further details regarding HIOH are available from the authors.

Usual care (control) group

These subjects were also initially visited in their home by a study worker, as described for intervention subjects, and completed the same follow-up telephone questionnaires. They otherwise received care from their usual providers, with no study intervention.

Follow-up data collection phone calls to measure study outcomes, including self-rated health, occurred at 2 and 4 weeks, 6 weeks (immediately post-intervention), and 6 and 12 months. As an incentive, subjects were paid $25 following completion of each scheduled follow-up data collection.

Measure

FFM personality factor

At baseline, subjects completed the 60-item NEO-five factor inventory (NEO-FFI; Costa & McCrae, 1992), an extensively validated abbreviated version of the NEO personality inventory-revised. The five 12-item scales in this measure tap the central FFM factors: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (refer Table 1 for example items). Scores were standardized (mean = 0, SD = 1) to facilitate interpretation. A higher score on a given NEO-FFI factor scale indicates a greater propensity to display the behavioural and dispositional tendencies of that factor Cronbach's alpha for the five scales ranged from .70 to .87 in this sample.

Self-rated health

At baseline, 2 and 4 weeks (during the intervention), 6 weeks (immediately following the intervention), and 6 months and 1-year follow-up, subjects completed the Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 questionnaire, which has been validated in population-based samples in a number of countries including the USA (McHorney, Ware, & Raczek, 1993; Ware, Keller, Gandek, Brazier, & Sullivan, 1995). Standardized scoring algorithms are employed to derive MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores (Ware, Kosinski, et al., 1995) ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better self-rated health. Both summary scales were designed so that a representative sample of the US population would have a mean score of 50 with a standard deviation of 10.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 10.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The main analytic approach was to conduct a series of linear regression models with each self-rated health measure (PCS-36 and MCS-36) as the dependent variable in each analysis. For analyses of relationships among personality factors and self-rated health at baseline, ordinary linear regressions of baseline health status measure scores on NEO-FFI factor (each factor included one at a time in each analysis, low vs. high status defined by median split in scores), age, and gender were performed.

For analyses examining the potential role of personality in moderating effects of the intervention on self-rated health, random effects linear regression was used to regress the health status measure at each time point on RCT group, NEO-FFI factor study time, and their interactions. Analyses also adjusted for age and gender. To facilitate interpretation of the findings of these analyses, adjusted mean (95% confidence interval, CI) health status scores by intervention group, time, and median split of personality factors are presented graphically. Prior analyses examining the impact of the intervention revealed no effect of the phone intervention (Jerant et al., 2009). Thus, to facilitate presentation, the phone and control groups were combined in these analyses. Analyses examining the FFM factors as continuous measures were conducted but are not presented, since findings were similar. Because there was no significant association between openness and MCS-36 scores (see Table 3), and because it is not part of the distressed personality profile, results of moderation, and interaction analyses for this personality factor are not presented. Complete results, including tables of interaction effects, are available from the authors on request.

Table 3.

Adjusted relationships of personality factors with baseline MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores

| Personality factor | Status | MCS-36 mean (95% confidence interval) |

PCS-36 mean (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroticism | Low | 52.6 (51.0, 54.2) | 32.4 (30.7, 34.1) |

| High | 39.3 (37.7, 40.8) | 34.6 (33.0, 36.2) | |

| Conscientiousness | Low | 42.4 (40.6, 44.1) | 33.1 (31.5, 34.8) |

| High | 49.0 (47.2, 50.8) | 33.9 (32.2, 35.5) | |

| Extraversion | Low | 40.7 (39.0, 42.4) | 32.4 (30.8, 34.1) |

| High | 50.8 (49.1, 52.5) | 34.7 (33.0, 36.3) | |

| Agreeableness | Low | 43.5 (41.6, 45.4) | 32.9 (31.2, 34.6) |

| High | 47.7 (45.9, 49.4) | 34.0 (32.4, 35.7) | |

| Openness | Low | 45.6 (43.7, 47.4) | 33.0 (31.4, 34.7) |

| High | 45.8 (44.0, 47.6) | 34.0 (32.3, 35.6) |

Note. MCS-36, SF-36 mental component summary score; PCS-36, SF-36 physical component summary score. Means are adjusted for age and gender. Low versus high status of personality factors defined by median split in scores.

Results

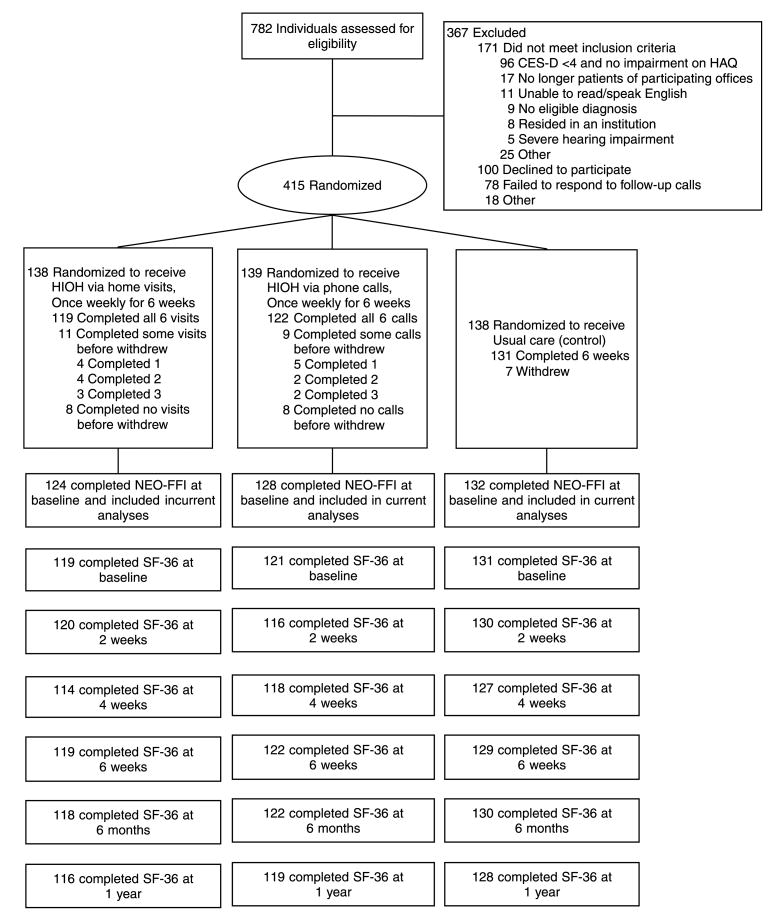

Figure 1 shows the flow of subjects through the RCT from enrolment through the end of the study. In all, 415 participants were randomized (home intervention = 138, phone intervention = 139, usual care = 138). Table 2 provides a summary of subjects' baseline characteristics. The sample was predominantly female, with a mean age of 60 years (range 41–95). Most reported two or more chronic conditions. Most subjects (94% or 384) completed the NEO-FFI at baseline. Reflecting the study's eligibility requirements, the mean MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores were comparatively low.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the study. CES-D, 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; HAQ, health assessment questionnaire; HIOH, homing in on health; NEO-FFI, NEO-five factor inventory.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Home (N = 138) | Other (N = 279) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 59.8 (11.2) | 60.7 (11.6) |

| Female, number (%) | 108 (78) | 213 (76.9) |

| Race/ethnicity, number (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 103 (75) | 225 (81) |

| Black | 20 (15) | 26 (9) |

| Other/declined to answer | 15 (10) | 28 (10) |

| Education level, number (%) | ||

| ≤ 12 years | 19 (14) | 42 (15) |

| 13–15 years | 53 (38) | 108 (39) |

| 16 years | 42 (30) | 80 (29) |

| > 16 years | 24 (17) | 42 (15) |

| Declined to answer | 0 (0) | 5 (2) |

| Uninsured, number (%) | 3 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Chronic conditions, number (%) | ||

| 1 | 55 (40) | 115 (41) |

| 2 | 51 (37) | 105 (38) |

| 3 | 18 (13) | 42 (15) |

| ≥ 4 | 14 (10) | 15 (5) |

| Specific study diagnoses, number (%)a | ||

| Arthritis | 83 (60) | 150 (54) |

| Depression | 59 (43) | 134 (48) |

| Diabetes | 64 (46) | 108 (39) |

| Asthma | 34 (25) | 64 (23) |

| Congestive heart failure | 17 (12) | 31 (11) |

| Chronic lung disease | 15 (11) | 28 (10) |

| Personality factors, mean (SD) | ||

| Agreeableness | 34.4 (4.8) | 33.3 (5.7) |

| Conscientiousness | 31.3 (7.5) | 32.0 (6.6) |

| Extraversion | 25.9 (8.0) | 26.0 (7.3) |

| Neuroticism | 20.6 (9.9) | 21.6 (9.2) |

| Openness | 28.2 (6.6) | 28.7 (6.2) |

| MCS-36 scores, mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 45.6 (14.2) | 45.5 (13.7) |

| 2 week follow-up | 48.7 (13.8) | 47.0 (13.1) |

| 4 week follow-up | 51.2 (11.7) | 48.9 (12.8) |

| 6 week follow-up | 51.6 (12.1) | 48.7 (12.5) |

| 6 month follow-up | 49.6 (13.7) | 47.1 (13.3) |

| 1 year follow-up | 51.2 (12.1) | 48.4 (12.4) |

| PCS-36 scores, mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 33.6 (12.0) | 33.9 (11.7) |

| 2 week follow-up | 35.4 (11.9) | 36.1 (11.3) |

| 4 week follow-up | 34.9 (12.3) | 36.9 (11.6) |

| 6 week follow-up | 34.9 (11.9) | 36.8 (11.3) |

| 6 month follow-up | 36.2 (12.0) | 37.3 (11.6) |

| 1 year follow-up | 35.1 (12.2) | 36.7 (11.9) |

Note. Other, telephone intervention and control groups combined; SD, standard deviation; MCS-36, SF-36 mental component summary score; PCS-36, SF-36 physical component summary score.

Percentages exceed 100 because many participants had more than one condition.

Baseline personality and self-rated health relationships

Table 3 displays adjusted relationships between the FFM personality factors and baseline MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores. The distressed personality profile – higher neuroticism, and lower conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness – was associated with lower baseline MCS-36 scores. There were no significant associations between personality factors and baseline PCS-36 scores.

Intervention main effects

Patients assigned to the home group had significantly better MCS-36 scores at 4 weeks (2.4 points higher, 95% CI = 0.0, 4.7) and 6 weeks (2.5 points higher, 95% CI = 0.2, 4.8) than did others, with no significant differences at 6 months or 1 year. There was no significant effect of the intervention on PCS-36 at any time.

Moderation of intervention effects by personality

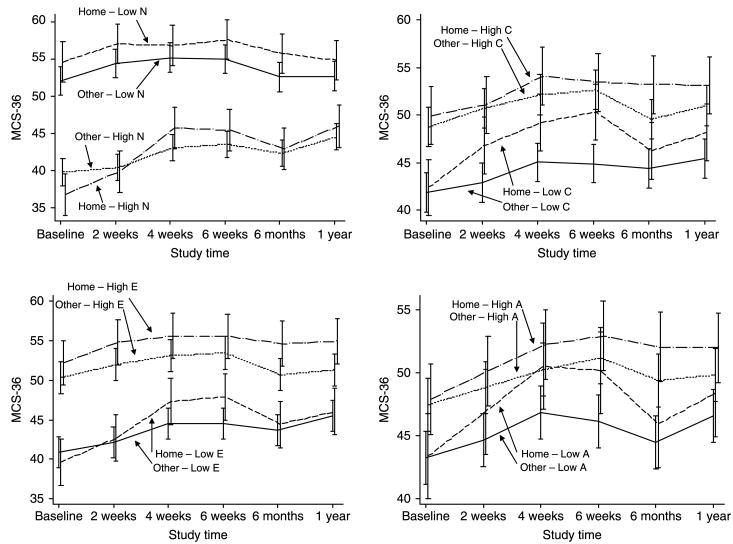

There was a statistically significant interaction between study group and conscientiousness at 6 weeks (z = 2.24, p = .025). Stratified analyses showed that the intervention (home vs. other) benefits on MCS-36 were confined to those with low conscientiousness (at 4 weeks, score 3.7 points higher in home group, 95% CI = 0.2, 71; at 6 weeks, score 5.0 points higher, 95% CI = 1.57, 8.4). The interaction effect had attenuated by 6 months. The other factors comprising the distressed personality profile – extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness – did not significantly moderate the effects of the intervention on MCS-36 scores, though there were non-significant trends in each case (see Figure 2). Openness did not significantly moderate the effects of the intervention on MCS-36 scores, and none of the FFM factors moderated intervention effects on PCS-36 scores (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Significant relationships among personality factors, group, time, and self-rated mental health. N, neuroticism; C, conscientiousness; E, extraversion; A, agreeableness. Other, telephone intervention and control groups combined; MCS-36, SF-36 mental component summary score. Low versus high status of each personality factor was defined by median split in scores.

Discussion

The study findings add to the limited research regarding personality and self-rated mental and physical health in people with chronic illnesses. They also provide new information on the potential moderating role of personality on the effects of chronic illness self-management interventions.

Regarding the baseline relationships, as hypothesized, trial participants with the distressed personality profile (Chapman et al., 2007b) – higher neuroticism and lower agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion – had lower baseline self-rated mental health, as measured by the MCS-36, than those with the opposite standing on these factors. Also as predicted, the strongest of these associations was for neuroticism.

These findings are generally consistent with those of the only prior study to examine this issue, which involved Dutch out-patients with mood and anxiety disorders. That study found a comparably strong association between neuroticism and MCS-36 scores, with weaker associations between extraversion and openness and MCS-36 scores and agreeableness and PCS-36 scores (van Straten et al., 2007). Prior research has linked higher levels of neuroticism to psychological distress and mood and anxiety disorders (Jylha & Isometsa, 2006; Kendler, Gatz, Gardner, & Pedersen, 2006). Individuals high in neuroticism tend to be more aware of and/or more likely to raise concerns about their health than others (Kressin, Spiro, & Skinner, 2000). The findings of the current and prior study suggest this tendency towards increased perception and/or reporting of health concerns may be greater in relation to psychological than to physical concerns.

Considerable differences in study samples and methodology probably contributed to the differences in findings related to effects of personality factors other than neuroticism on mental and physical health status in the prior and current study. In particular, the lack of association between baseline personality and physical health status in our study could reflect the mitigating influences of our study chronic illnesses, which were less prevalent in the Dutch study sample. Duration of diagnosis might also have played a role: most of our participants had been living with their chronic conditions for some time, and the influence of personality on self-rated health may vary at different points in the chronic illness trajectory.

Regarding effects of the intervention, there was a short-term main effect of in-home (but not telephone) HIOH on self-rated mental health: 4 and 6 week MCS-36 scores were significantly better in the home intervention group as compared with others, an effect that attenuated by 6 months follow-up. HIOH had no significant effects on self-rated physical health at any follow-up point. While the reasons for this finding are not fully clear, it may in part reflect sample homogeneity or temporal issues, as the role of personality might vary at different points in the chronic illness trajectory. It may also be that the small to moderate effect of the intervention on illness management self-efficacy (effect size 0.3) is not of sufficient magnitude to lead to significant changes in physical health and functioning. Finally, self-efficacy is conceptually more closely related to mental than physical health (Bandura, 1997). The only prior 1-year RCT of a CDSMP variant also found only short-term effects on self-rated health (with respondents rating their health globally as excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor on a single question), with no effects at 1 year (Lorig et al., 2006). Though comparisons between the studies are limited somewhat by their use of different self-rated health measures, it appears the CDSMP and its variants may result in small to moderate and relatively short-term effects on self-rated health, possibly limited to effects on mental health.

In partial support of hypotheses regarding moderating effects of personality, analyses revealed short-term benefits of the home intervention on MCS-36 scores were present only in those with low conscientiousness, an interaction that attenuated by 6 months. This finding echoes the results of the prior interim analysis from the RCT, which found beneficial effects of in-home HIOH on illness management self-efficacy were confined to patients lower in conscientiousness (Franks et al., 2009). There are several possible explanations for these findings. First, low conscientiousness individuals tended to have lower illness management self-efficacy at baseline than did other participants in the RCT, regardless of study arm. Thus, they appeared to have the most room for improvement in self-efficacy, the putative mediator of illness self-management interventions such as HIOH, and when assigned to an intervention that aggressively targeted this deficit, both self-efficacy and self-rated mental health improved.

Additionally, dispositional tendencies that cluster under the conscientiousness category may affect the way participants perceive and respond to specific components, demands, and features of interventions like HIOH (Christensen, 2000). For example, core dispositional elements of conscientiousness are self-control, organization, and goal-orientation. Low levels of these tendencies are likely to give rise to worse health behaviours within the disease self-management domain, including poor diet and exercise habits (Bogg & Roberts, 2004; Goldberg & Strycker, 2002; Roberts, Walton, & Bogg, 2005). Several aspects of the HIOH intervention would appear particularly beneficial to individuals low in conscientiousness. For example, the concept of ‘action planning’, or setting and periodically re-evaluating and revising personal health goals, is emphasized throughout the intervention. This instructive scaffolding may have been particularly useful to less conscientious persons, who tend to be disorganized, have lower levels of self-control, and are less likely to set and follow through with goals. Gaining mastery of such habits may foster improved mental health. Such hypotheses remain speculative, since they were not tested in the current study. Future studies might examine whether the components of chronic illness self-management interventions interface with participant dispositional tendencies.

None of the other three factors that make up the distressed personality type – agreeableness, extraversion, and neuroticism – significantly moderated short-term intervention effects on MCS-36 scores, though Figure 2 indicates there were nonsignificant trends in this direction. The reasons why the study findings did not support hypothesized moderating effects of these three personality factors on self-rated mental health are not clear, though again the small to moderate effect of the intervention on self-efficacy may have played a role. The absence of personality moderation of intervention effects on self-rated physical health scores is perhaps not surprising, since the concept of self-efficacy is again more closely related to mental than physical health (Bandura, 1997). Alternatively, this finding might primarily reflect the lack of HIOH intervention effects on physical health status in our sample in general.

Identification of patients more or less likely to benefit from chronic disease interventions can facilitate allocation of resources towards suitable candidates, improving the interventions' efficiency, or ratio of clinical benefit to delivery effort (Issel, 2004). The utility of targeting medical interventions to those most likely to benefit is well-established, though it has thus far primarily been employed to guide prescription drug therapy. For example, a widely employed evidence-based algorithm to determine the need for and intensity of drug therapy for hyperlipidemia encourages careful consideration of each individual's overall risk for cardiovascular disease, rather than basing treatment solely on serum lipid values (National Cholesterol Education Program, 2001). Our findings suggest this approach might also be useful in targeting illness self-management interventions to those most likely to benefit – in the case of HIOH, individuals low in conscientiousness. Brief (≤ 5 min to administer), valid, and reasonably reliable personality measures have been developed that could facilitate such targeting in clinical settings (Benet-Martinez, 1998; Gustavsson, 2003).

Future trials of chronic illness self-management interventions might block or stratify on participants' conscientiousness standing, and/or explore the utility of offering alternative versions of the interventions to those who the current results suggest are unlikely to respond favourably to the ‘standard’ programmes. The goal would be to begin to shift the emphasis from exclusively studying whether or not such interventions ‘work’ to determining in whom they are likely to be most effective.

This study had some limitations. It involved a sample of chronically ill out-patients who volunteered for a RCT, which may limit generalizability to other groups and settings. Mean MCS-36 and PCS-36 scores were somewhat lower than in the general population (Ware, Kosinski, et al., 1995). Likewise, mean neuroticism scores were somewhat higher and mean scores for the other FFM factors somewhat lower than in the general population (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Women were also slightly overrepresented compared with the general primary care population, in part due to the higher prevalence of depression (one of the six study diagnoses) in women relative to men (Kuehner, 2003). Finally, several hypotheses were examined, raising the possibility of chance findings due to multiple hypothesis testing. However, the consistency of the current results with those in two prior relevant studies involving the distressed personality profile suggests it is unlikely our findings arose due to chance.

In conclusion, this study found significant relationships between several FFM personality factors and self-rated mental health, but no significant relationships between personality and self-rated physical health. Participants in a RCT of an illness self-management intervention with the distressed personality profile – higher neuroticism and lower agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion – had worse baseline self-rated mental health than participants with opposite standing on these factors. Additionally, one of the FFM factors, conscientiousness, was found to moderate the short-term beneficial effects of the illness self-management intervention on self-rated mental health, with non-significant trends observed for the other three factors in the distressed profile. The differences observed in study findings for self-rated mental versus physical health emphasize the importance of employing measures that separately capture each facet when examining relationships among personality, intervention effects, and self-rated health. They also underscore the need for additional studies exploring such relationships, involving a wide array of study designs (e.g. observational vs. interventional), samples, and settings, to determine whether important contextual differences in associations may exist.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant number R01HS013603 and National Institute of Health grants number T32 MH073452, K08AG031328, and K24MH072712.

References

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martinez V, John DP. Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;75(8):729–750. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.3.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):887–919. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Personality traits, education, and health-related quality of life among older adult primary care patients. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2007a;62(6):P343–P352. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.6.p343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. The distressed personality type: Replicability and general health associations. European Journal of Personality. 2007b;21(7):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman BP, Lyness JL, Duberstein PD. Personality and medical illness burden among older adults in primary care. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2007;69(3):277–282. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3180313975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen AJ. Patient-by-treatment context interaction in chronic disease: A conceptual framework for the study of patient adherence. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(3):435–443. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO personality inventory and NEO five factor inventory: Professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, Jr, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: The revised NEO personality inventory in the year 2000. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;68(1):86–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denollet J, Conraads VM, Brutsaert DL, De Clerck LS, Stevens WJ, Vrints CJ. Cytokines and immune activation in systolic heart failure: The role of type D personality. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2003;17(4):304–309. doi: 10.1016/s0889-1591(03)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dongbo F, Fu H, McGowan P, Shen Y, Zhu L, Yang H, et al. Implementation and quantitative evaluation of chronic disease self-management programme in Shanghai, China: Randomized controlled trial. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81:174–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks P, Chapman B, Duberstein P, Jerant A. Five factor model personality factor moderated the effects of an intervention to enhance chronic disease management self-efficacy. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14(3):473–478. doi: 10.1348/135910708X360700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS. Long-term relations of personality and health: Dynamisms, mechanisms, tropisms. Journal of Personality. 2000;68(6):1089–1107. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1980;23(2):137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist. 1993;48(1):26–34. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.48.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Strycker LA. Personality traits and eating habits: The assessment of food preferences in a large community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;32(1):49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths C, Motlib J, Azad A, Ramsay J, Eldridge S, Feder G, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a lay-led self-management programme for Bangladeshi patients with chronic disease. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55(520):831–837. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson JP, Jonsson EG, Linder J, Weinryb RM. The HPS inventory: Definition and assessment of five health-relevant personality traits from a five-factor model perspective. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;35(1):69–89. [Google Scholar]

- Habra ME, Linden W, Anderson JC, Weinberg J. Type D personality is related to cardiovascular and neuroendocrine reactivity to acute stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2003;55(3):235–245. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improving Chronic Illness Care. The chronic care model. Self-management support. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Self-Management_Support&s=22.

- Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: Criterion validity of the 10-item center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES-D) Archives of Internal Medicine. 1999;159(15):1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issel LM. Health program planning and evaluation: A practical, systematic approach for community health. chap. 8. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 2004. Process evaluation. Measuring inputs and outputs. [Google Scholar]

- Jerant AF, Moore M, Franks P. Home-based, peer-led chronic illness self-management training: Findings from a one-year randomized controlled trial. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7:319–327. doi: 10.1370/afm.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerant AF, von Friederichs-Fitzwater MM, Moore M. Patients' perceived barriers to active self-management of chronic conditions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2005;57(3):300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylha P, Isometsa E. The relationship of neuroticism and extraversion to symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general population. Depression and Anxiety. 2006;23(5):281–289. doi: 10.1002/da.20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. Personality and major depression: A Swedish longitudinal, population-based twin study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2006;63(10):1113–1120. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy A, Reeves D, Bower P, Lee V, Middleton E, Richardson G, et al. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of a national lay-led self care support programme for patients with long-term conditions: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2007;61(3):254–261. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kressin NR, Spiro A, III, Skinner KM. Negative affectivity and health-related quality of life. Medical Car. 2000;38(8):858–867. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehner C. Gender differences in unipolar depression: An update of epidemiological findings and possible explanations. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia. 2003;108(3):163–174. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kupper N, Denollet J. Type D personality as a prognostic factor in heart disease: Assessment and mediating mechanisms. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2007;89(3):265–276. doi: 10.1080/00223890701629797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Holman H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Laurent DD, Plant K. Internet-based chronic disease self-management: A randomized trial. Medical Care. 2006;44(11):964–971. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000233678.80203.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Medical Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Wortman CB, Vickers RR, Jr, Kusulas JW, Hervig LK. The five-factor model of personality as a framework for personality-health research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(2):278–286. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae RR, Costa PT. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. 2nd. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mroczek DK, Spiro A., III Personality change influences mortality in older men. Psychological Science. 2007;18(5):371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Cholesterol Education Program. Executive Summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;285(19):2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Kuncel NR, Shiner R, Caspi A, Goldberg LR. The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2(4):313–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Bogg T. Conscientiousness and health across the life course. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9(2):156–168. [Google Scholar]

- Samsa G, Edelman D, Rothman ML, Williams GR, Lipscomb J, Matchar D. Determining clinically important differences in health status measures: A general approach with illustration to the health utilities index mark 2. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:141–155. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199915020-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford Patient Education Research Center. Stanford self-management programs. 2008 Retrieved from http://patienteducation.stanford.edu/programs/

- Swerissen H, Belfrage J, Weeks A, Jordan L, Walker C, Furler J, et al. A randomised control trial of a self-management program for people with a chronic illness from Vietnamese, Chinese, Italian and Greek backgrounds. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;64(1–3):360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Kingdom Department of Health. Saving lives, our healthier nation. 2008 Retrieved from http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/cm43/4386/4386.htm.

- van Straten A, Cuijpers P, van Zuuren FJ, Smits N, Donker M. Personality traits and health-related quality of life in patients with mood and anxiety disorders. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16(1):1–8. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9124-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Keller SD, Gandek B, Brazier JE, Sullivan M. Evaluating translations of health status questionnaires. Methods from the IQOLA project. International Quality of Life Assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care. 1995;11(3):525–551. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300008710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: Summary of results from the medical outcomes study. Medical Care. 1995;33(Suppl 4):AS264–AS279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]