Abstract

BACKGROUND

Using a water pipe to smoke tobacco is increasing in prevalence among US college students, and it may also be common among younger adolescents. The purpose of this study of Arizona middle and high school students was to examine the prevalence of water-pipe tobacco smoking, compare water-pipe tobacco smoking with other forms of tobacco use, and determine associations between sociodemographic variables and water-pipe tobacco smoking in this population.

METHODS

We added items assessing water-pipe tobacco smoking to Arizona’s 2005 Youth Tobacco Survey and used them to estimate statewide water-pipe tobacco smoking prevalence among various demographic groups by using survey weights. We also used multiple logistic regression to determine which demographic characteristics had independent relationships with each of 2 outcomes: ever use of water-pipe to smoke tobacco and water-pipe tobacco smoking in the previous 30 days.

RESULTS

Median age of the sample was 14. Accounting for survey weights, among middle school students, 2.1% had ever smoked water-pipe tobacco and 1.4% had done so within the previous 30 days. Among those in high school, 10.3% had ever smoked from a water pipe and 5.4% had done so in the previous 30 days, making water-pipe tobacco smoking more common than use of smokeless tobacco, pipes, bidis, and kreteks (clove cigarettes). In multivariate analyses that controlled for covariates, ever smoking of water-pipe tobacco was associated with older age, Asian race, white race, charter school attendance, and lack of plans to attend college.

CONCLUSIONS

Among Arizona youth, water pipe is the third most common source of tobacco after cigarettes and cigars. Increased national surveillance and additional research will be important for addressing this threat to public health.

Keywords: water pipe, narghile, hookah, tobacco, smoking, adolescence, high school

A water pipe, also known as a hookah, narghile, or shisha-pipe, consists of a head into which tobacco is placed, a body that is half-filled with water, and a hose through which the user inhales. The tobacco, which is generally moist, flavored, and sweetened, is heated by using a piece of charcoal. Smoke inhalation can be substantial: a single water-pipe use episode can last 30 to 60 minutes and can involve more than 100 inhalations, each ~500 mL in volume.1,2 Thus, whereas smoking a single cigarette might produce a total of ~500 to 600 mL of smoke,3 a single water-pipe use episode might produce ~50 000 mL of smoke.

Water-pipe smoke contains many of the same toxicants as cigarette smoke.1,4 Not surprisingly, carbon monoxide is found in water-pipe users’ breath5–7 and nicotine is found in their blood,8 to the extent that blood nicotine of a daily water-pipe user is similar to that of an individual who smokes 10 cigarettes per day.9 Although more epidemiologic research is needed, water-pipe tobacco smoking has been associated with substantial harm, including cancer, cardiovascular disease, decreased pulmonary function, and nicotine dependence.7,10–12

In the United States, the prevalence of this behavior seems to be growing, especially among college students. Nearly 300 new water-pipe cafes opened in the United States between 1999 and 2004, mostly in college towns.13–15 Convenience sample surveys have suggested 30-day college water-pipe tobacco smoking rates as high as 15% to 20%,16,17 and a college-based random sample survey found a 30-day use rate of 9.5%, a 1-year use rate of 30.6%, and an ever use rate of 40.5%.18

Although we are learning more about water-pipe tobacco smoking among college students, there is little information concerning how common this form of tobacco use is among US high school students. The behavior clearly can appeal to this age group; surveys indicate previous 30-day water-pipe tobacco smoking rates as high as 25% among Israeli and Lebanese high school students,19,20 and 22% among a sample of Arab American high school students in the US Midwest.21 However, we are aware of no published studies reporting state- or national-level water-pipe tobacco smoking prevalence among US high school students.

Identifying demographic characteristics associated with water-pipe tobacco smoking in the United States may help focus prevention efforts. Among college students, water-pipe tobacco smoking is associated with white race, younger age, and membership in a fraternity or sorority.16–18 Unfortunately, no such information is available for representative samples of high school students. Thus, in 2005, the state of Arizona included water- pipe tobacco smoking items in its Youth Tobacco Survey (YTS). To our knowledge, the 2005 Arizona YTS represents the first statewide standardized assessment of this behavior among US high school students.

The purpose of this study was to examine the 30-day and lifetime prevalence of water-pipe tobacco smoking in a statewide sample of high school students in Arizona. In addition, we aimed to compare the prevalence of water-pipe tobacco smoking with that of other forms of tobacco use and to determine associations between sociodemographic variables and water-pipe tobacco use in this population. We hypothesized that water-pipe tobacco smoking would be present, but that it would be less common in high school than is cigarette smoking. Based on previous information from other age groups, we also hypothesized that it would be associated with male gender and white race. Finally, consistent with uptake patterns of other substance use during high school, we expected that use would be associated with increased age.

METHODS

Design, Participants, and Setting

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides technical assistance to states to administer a standardized questionnaire, the YTS, for the surveillance of youth tobacco use. The Arizona Department of Education, in collaboration with the Arizona Department of Health Services, administered the YTS to Arizona students in grades 6 through 12 during the spring semester of the 2004–2005 school year. The complete Arizona YTS contained 84 multiple-choice items modeled after the standard Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–recommended core YTS questionnaire,22 with additional state-specific items. It was designed to be easily administered during a 45-minute class period. During this administration, Arizona included items assessing water-pipe tobacco smoking.

Sampling

Separate middle school and high school samples were selected from all public district schools (standard public schools that draw from 1 particular district) and charter schools (that may draw from multiple districts) in Arizona. This selection strategy produced 4 separate samples: (1) district high school; (2) district middle school; (3) charter high school; and (4) charter middle school.22 For each sample, the sampling frame consisted of all schools containing students enrolled in grades 6 through 8 for the middle schools and grades 9 through 12 for the high schools for both district and charter schools. All schools with more than 3 students in the specified grade ranges were included in the sampling frame. A 2-stage cluster sample design was used to produce a representative sample of middle school students in grades 6 through 8 and high school students in grades 9 through 12; however, charter school students were oversampled to have enough statistical power to conduct stratified analyses with this subgroup.22 PC-Sample was used to draw all 4 samples.23

Recruitment, Permission, and Data Collection

Selected schools were recruited in early January 2005. Letters were followed by telephone calls directly to the superintendents, school directors, or principals. After schools agreed to participate, a school contact person was assigned, classes were selected, and a date for data collection was scheduled. The type of permission form (active or passive) used was left to the discretion of the school. The overwhelming majority of schools (139 of 156; 89%) opted to use passive parental permission forms.

Data collection was conducted by trained personnel and began in late January and continued through the middle of May 2005. One data collector went to each school and administered the survey to the selected classes. Teachers remained in the classrooms to identify students who did not have permission to participate in the survey and maintain order during data collection. Teachers provided alternate activities to nonparticipating students. Student make-ups were conducted to maximize response rates. Make-up sessions were often needed at schools because of student absence or lack of parental consent when the initial administration occurred. Response rates were high, with 93% of selected schools participating (156 of 186). Furthermore, 86% of eligible students provided evaluable data (6594 of 7646), for an overall response rate of 80%.

Measures

The Arizona YTS asked 2 items related to water-pipe use. The first asked, “Which of the following tobacco products have you ever tried, not including cigarettes? (You can choose one answer or more than one.),” for which “hookah” was 1 of the possible responses. The other item asked a similar item that was phrased, “During the past 30 days, which of the following tobacco products have you used, not including cigarettes?” Thus, we examined each of the 2 water-pipe tobacco smoking outcomes assessed in the Arizona YTS: (1) 30-day water-pipe smoking; and (2) ever water-pipe smoking.

To compare water-pipe tobacco smoking with use of other tobacco products, we also used YTS assessments of 30-day and ever use of other tobacco products. Finally, we examined all survey demographic characteristics potentially related to water-pipe use, including age, gender, race, type of school (charter versus district), and plans to attend college. We included “plans to attend college” in our multivariable models because this construct, which approximates socioeconomic status, has been inversely associated with substance use.24,25

Analysis

Sampling weights were applied to all records, and all analyses were conducted by using weighted data with Stata 9.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). After providing descriptive analysis of participants, we used bivariate and multiple logistic regression to determine which demographic characteristics had independent relationships with the outcomes. Our primary regression models included all measured covariates. We omitted students with any missing data from our analyses, a strategy that likely did not affect our results, because <2% of our sample had missing data. For our primary models, we defined statistical significance as a 2-tailed α value of .05.

RESULTS

We received data from 6594 respondents, representing 483 586 adolescents. Median age was 14, and all grades from 6 through 12 were well represented. The sample was 48% male. The sample was largely white (47.2%) and Hispanic or Latino (33.8%). Fewer respondents identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native (7.9%), black (7.0%), Asian American (2.7%), and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (1.4%). Almost 40% of the sample attended a charter school (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of Water-Pipe Tobacco Smoking in Arizona 6th- to 12th-Grade Students (2005)

| Whole Sample, n (%)a |

Ever Smoked Tobacco From a Water Pipe,% (95% CI)b |

Pb | Smoked Tobacco From a Water Pipe in the Previous 30 d,% (95% CI)b |

Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants | 6594 (100) | 6.4 (5.7–7.1) | 3.5 (2.9–4.0) | ||

| Grade level | |||||

| 6th | 1035 (15.9) | 1.2 (0.2–2.1) | <.001 | 0.8 (0.01–1.5) | <.001 |

| 7th | 1073 (16.4) | 1.8 (0.7–3.0) | 1.7 (0.6–2.8) | ||

| 8th | 1115 (17.1) | 3.3 (2.1–4.5) | 1.7 (0.9–2.6) | ||

| 9th | 889 (13.6) | 6.6 (4.7–8.5) | 4.3 (2.7–5.8) | ||

| 10th | 850 (13.0) | 8.4 (6.1–10.7) | 4.9 (3.1–6.8) | ||

| 11th | 877 (13.4) | 12.9 (10.3–15.6) | 5.4 (3.6–7.2) | ||

| 12th | 688 (10.5) | 15.1 (11.9–18.3) | 7.3 (5.0–9.7) | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 3173 (48.1) | 7.3 (6.2–8.5) | .01 | 4.2 (3.3–5.1) | .008 |

| Female | 3385 (51.3) | 5.5 (4.5–6.4) | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | ||

| Race | |||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 492 (7.9) | 3.2 (1.4–5.0) | <.001 | 2.2 (0.6–3.8) | .02 |

| Asian American | 171 (2.7) | 7.9 (3.1–12.6) | 3.6 (0.5–6.8) | ||

| Black | 439 (7.0) | 3.9 (1.7–6.2) | 2.7 (0.8–3.5) | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 2121 (33.8) | 4.2 (3.2–5.3) | 2.7 (1.8–3.5) | ||

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 86 (1.4) | 10.1 (2.4–18.0) | 7.4 (0.03–14.8) | ||

| White | 2961 (47.2) | 8.5 (7.3–9.7) | 4.1 (3.2–5.0) | ||

| School type | |||||

| Regular | 4006 (60.8) | 6.0 (5.3–6.8) | <.001 | 3.3 (2.7–3.9) | <.001 |

| Charter | 2588 (39.3) | 10.5 (9.1–11.8) | 5.5 (4.4–6.5) | ||

| Plans to attend college | |||||

| Definitely yes | 4502 (72.6) | 5.3 (4.5–6.1) | <.001 | 3.1 (2.4–3.7) | .03 |

| Not definitely yes | 1698 (27.4) | 9.5 (7.7–11.3) | 4.5 (3.2–5.7) |

CI indicates confidence interval.

Data do not always sum to total sample sizes because of missing data. Percentages are based on the total for each category and may not total 100 because of rounding.

These were χ2 analyses that used Arizona YTS sampling weights.

Accounting for survey weights, 6.4% of Arizona middle and high school students had ever smoked tobacco from a water pipe, and 3.5% had done so in the previous 30 days. Water-pipe tobacco smoking increased significantly with grade level (Table 1). Among middle school students (grades 6–8), 2.1% had ever smoked waterpipe tobacco and 1.4% had done so within the previous 30 days. Among those in high school (grades 9–12), 10.3% had ever smoked from a water pipe and 5.4% had done so in the previous 30 days.

Other demographic comparisons are shown in Table 1. Compared with females, males reported more frequent ever use of a water pipe (7.3% vs 5.5%; P = .001) and more frequent use over the previous 30 days (4.2% vs 2.7%; P = .008). Water-pipe tobacco smoking differed significantly by race (Table 1). Ever use was most common among Pacific Islander students (10.1%), followed by white students (8.5%), and Asian American students (7.9%). American Indian students had the lowest rates of water-pipe tobacco smoking (3.2% ever, 2.2% previous 30 days). Charter school students were more likely than regular students to have smoked from a water pipe ever (10.5% vs 6.0%; P < .001) or in the previous 30 days (5.5% vs 3.3%; P < .001). Compared with those who definitively planned to attend college, those who did not have definite plans to attend college were more likely to have smoked from a water pipe ever (9.5% vs 5.3%; P < .001) or in the previous 30 days (4.5% vs 3.1%; P = .03).

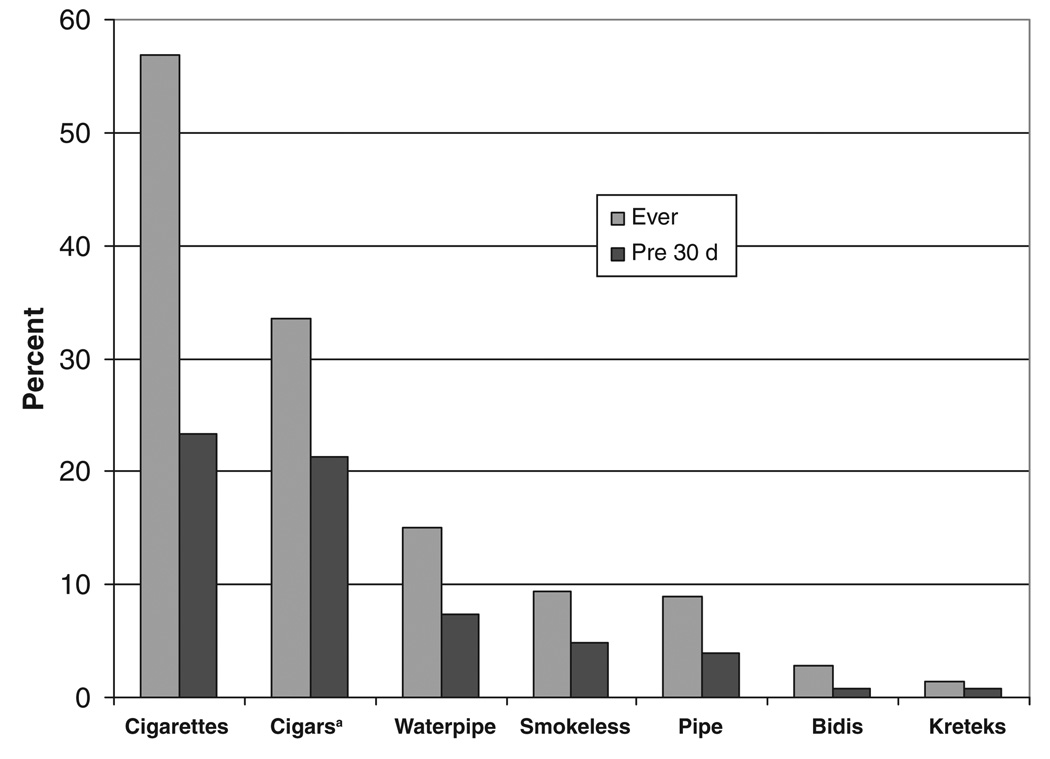

Water-pipe tobacco smoking was particularly common among 12th-graders, as 15.1% of Arizona students reported having ever smoked tobacco from a water pipe and 7.3% having done so in the previous 30 days. This made water-pipe tobacco smoking the third most common source of tobacco for young people this age (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

High school seniors’ use of tobacco products in Arizona (2005). All percentages were computed by using survey weights. a Includes cigarillos and “little cigars.”

In multivariate analyses that controlled for covariates, the odds of ever smoking tobacco from a water pipe were higher among older compared with younger students, Asian American and white students compared with American Indian or Alaska Native students, students attending charter school compared with regular school, and among students who were not definitely planning to attend to college compared with students who definitely were planning to attend college (Table 2). The odds of previous 30-day use were higher among older compared with younger students, males compared with females, students attending charter school compared with regular school, and among students who were not definitely planning to attend to college compared with students who definitely were planning to attend college (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Relationships Between Water-Pipe Tobacco Smoking and Sociodemographic Data

| Ever Smoked Tobacco From a Water Pipe |

Smoked Tobacco From a Water Pipe in the Previous 30 d |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) Unadjusted |

OR (95% CI) Adjusteda |

OR (95% CI) Unadjusted |

OR (95% CI) Adjusteda |

|

| Grade level | 1.5 (1.4–1.7)b | 1.6 (1.4–1.7)b | 1.4 (1.3–1.5)b | 1.4 (1.2–1.5)b |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Female | 0.7 (0.6–0.9)b | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) | 0.6 (0.5–0.9)b | 0.6 (0.4–0.9)b |

| Race | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Asian American | 2.6 (1.1–6.2)b | 3.2 (1.2–8.4)b | 1.7 (0.5–5.5) | 2.0 (0.6–7.0) |

| Black | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 1.3 (0.5–3.5) | 1.2 (0.4–3.5) | 1.0 (0.3–3.4) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) | 1.4 (0.7–2.9) | 1.2 (0.5–2.8) | 1.4 (0.6–3.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 3.4 (1.2–9.6)b | 2.5 (0.7–9.4) | 3.6 (0.96–13.4) | 2.5 (0.5–12.1) |

| White | 2.8 (1.5–5.1)b | 3.2 (1.6–6.4)b | 1.9 (0.9–4.3) | 2.1 (0.9–5.0) |

| School type | ||||

| Regular | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Charter | 1.8 (1.5–2.2)b | 1.5 (1.2–1.8)b | 1.7 (1.3–2.2)b | 1.4 (1.1–1.9)b |

| Plans to attend college | ||||

| Definitely yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Not definitely yes | 1.9 (1.5–2.4)b | 2.0 (1.6–2.8)b | 1.5 (1.03–2.1)b | 1.5 (1.02–2.2)b |

OR indicates odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Adjusted for all variables in the table.

P < .05

DISCUSSION

In Arizona, ~2% of middle school students and 10% of high school students report some history of water-pipe tobacco smoking, making it more common than many other tobacco-use methods. In this population, ever water- pipe tobacco smoking was associated independently with increasing age, Asian race, white race, attendance at a charter school, and lack of plans to attend college.

The prevalence results are consistent with reports from college campuses16,18,26 and highlight the need for intervention to prevent water-pipe tobacco smoking among US youth. Also in our sample, higher point estimates were observed for water-pipe tobacco smoking among Pacific Islander students and Asian American students (although sample size limited statistical power in some instances). These results may reflect the history of water-pipe tobacco smoking, as the practice has its roots in the Indian subcontinent as well as the Middle East.27

In our sample, water-pipe smoking was more common among older youth. This is similar to uptake patterns of other substance use,28 likely reflecting the new environmental and social milieu of high school. Interestingly, in college samples, higher rates of water-pipe tobacco smoking are often observed among younger students.18 This seeming discrepancy may reflect an interaction between a desire to socialize in peer groups and age-limited access to venues where alcohol is served. Individuals who are <21 years of age who seek opportunities to socialize with peers may be stymied by restricted access to alcohol-serving venues, but may find easier access to “hookah cafés” and similar establishments that often do not serve alcohol. Thus, water-pipe tobacco smoking may be particularly attractive and accessible to older high school students and younger college students.

An unfortunate byproduct of this early exposure to tobacco smoking via water pipe may be an increased likelihood of cigarette smoking. In 1 study of Arab American adolescents, the odds of experimenting with cigarettes were 8 times greater for those who had ever smoked tobacco by using a water pipe.29 This issue of water-pipe tobacco smoking as a “gateway” to cigarette smoking in the United States requires additional examination among all age groups.

We found that, compared with district school students, charter school students were more likely to smoke water-pipe tobacco. In Arizona, charter schools are public schools, with 80% of their funding coming from local school districts and the state. They offer parents and students alternatives to neighborhood district schools in that they operate independently, choose their own academic focus, have fewer students and, therefore, typically have smaller class sizes, and can hire teachers that are not state certified. Charter schools are known to serve different clientele than district schools because parents must actively seek them out. At the high school level, there are several college preparatory charter schools that cater to high academic achievers, but many schools also serve at-risk students who have left the traditional public school system and are looking for a “last resort.”30 Thus, our finding that charter school students were more likely to smoke water-pipe tobacco may reflect this population’s tendency toward risk-taking behavior.

Similarly, we found that water-pipe use was twice as likely among youth who did not report definite intentions to attend college. Because water-pipe tobacco smoking has been studied primarily in college-based studies, there has been a tendency to minimize its importance as a fad among higher-achieving, lower-risk youth. Our results, however, suggest that it may be more similar to other types of tobacco use than previously thought, with higher uptake among higher-risk youth.

It is unclear whether the prevalence numbers in other states will be higher than, lower than, or equal to those in Arizona. Anecdotally, compared with other states, Arizona does seem to have more water-pipe cafés, most of which are located in Tempe (www.hookah-bars.com). However, it is also likely that prevalence would be higher in the many other states with a higher concentration of colleges and/or urban centers compared with Arizona. Finally, there are likely to be other environmental and regional factors that may be associated with water-pipe tobacco smoking prevalence, and future studies should begin to assess these variables.

Regardless of the US state, there are several reasons that, relative to other types of tobacco, water-pipe tobacco smoking may continue to increase among youth. First, water-pipe tobacco smoking is less physically harsh than smoking from a cigarette or a cigar (eg, the smoke is cooler and easier to inhale1), and the tobacco is commonly sweetened and flavored (eg, apple, bubble gum, chocolate, frappucino, mint, orange soda, root beer, watermelon). Second, although educational programs related to the dangers of cigarette smoking are commonplace, water-pipe tobacco smokers and other young people downplay the potential for harm or addictiveness from water-pipe tobacco smoking.17,18,26 Finally, legislation that limits cigarette smoking in public places often exempts water-pipe smoking venues,14 thus giving the appearance that the risks of exposure to tobacco smoke generated by a water pipe are somehow less than the risks of exposure to tobacco smoke generated by a cigarette.

For all of these reasons, an important implication of our findings is that continued surveillance and water-pipe–specific prevention efforts are required. Presently, we are aware of no national surveys that include items related to water-pipe tobacco smoking, although other forms of tobacco use that were less common in this sample are included (eg, smokeless tobacco, pipes, bidis, and kreteks, also known as clove cigarettes). Understanding the prevalence of water-pipe tobacco smoking nationally, particularly among high school and college students, will help focus the development and assess the effectiveness of prevention programs. Prevention program development will be further aided by quantitative and qualitative studies assessing factors such as the (1) contexts in which water-pipe tobacco is used among high school and college students, and (2) beliefs and attitudes that are associated with water-pipe use in these populations.

Similarly, it is important for clinicians to be aware of this emerging trend. Current guidelines instruct clinicians to ask about all types of tobacco use, including smokeless tobacco.31 If indeed water-pipe tobacco smoking is more common and potentially more harmful than smokeless tobacco,12 clinicians should similarly inquire about and counsel regarding this type of tobacco use.

LIMITATIONS

This study used cross-sectional data, so causality or temporal relationships cannot be inferred from the results. In addition, the survey was limited to 2 items assessing water-pipe tobacco smoking history: ever-smoking and previous 30-day smoking. More items that provide detailed information regarding water-pipe smoking patterns in this population will help fully delineate water-pipe use behaviors. Also, these data came from 1 US state, and results from surveys of middle and high school students in other states may differ; national studies are clearly merited. Similarly, the survey did not assess knowledge, attitudes, or beliefs related to water-pipe tobacco smoking. However, our data provide a crucial starting point for future studies addressing these limitations.

CONCLUSIONS

These data from Arizona show that water-pipe tobacco smoking is common among youth <18 years of age and that it is associated with increased age, certain racial groups, and markers of high-risk behavior. Increased surveillance and additional research are necessary to address this growing threat to public health.

What’s Known on This Subject

Tobacco smoking by using a water pipe (ie, hookah or narghile) seems to be proliferating on US college campuses. Water-pipe tobacco smoke contains many of the same toxicants as cigarette smoke, and it has been associated with both harm and addiction.

What This Study Adds

Among Arizona youth, water pipe is the third most common source of tobacco use after cigarettes and cigars. For those in high school, ever use of water pipe was 10.3%, and 30-day use was 5.4%. Increased national surveillance in this population is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr Primack was supported in part by a physician faculty scholar award from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a career development award from the National Cancer Institute (K07-CA114315), and a grant from the Maurice Falk Foundation. Dr Primack had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr Walsh and all data collection for this study were supported in part by funding from the Arizona Department of Health Services Bureau of Tobacco Education and Prevention. Dr Eissenberg was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA103827 and R01-CA120142), as well as the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA024876). None of these organizations had any role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviation

- YTS

Youth Tobacco Survey

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online: http://www.pediatrics.org/misc/reprints.shtml

REFERENCES

- 1.Shihadeh A. Investigation of the mainstream smoke aerosol of the argileh water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003;41(1):143–152. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(02)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shihadeh A, Azar S, Antonius C, Haddad A. Towards a topographical model of narghile water-pipe cafe smoking. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79(1):75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djordjevic MV, Stellman SD, Zang E. Doses of nicotine and lung carcinogens delivered to cigarette smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(2):106–111. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocacrbons, carbon monoxide, “tar,” and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43(5):655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaouachi K. The medical consequences of narghile (hookah, shisha) use in the world. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2007;55(3):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafagoj YA, Mohammed FI. Levels of maximum endexpiratory carbon monoxide and certain cardiovascular parameters following hubble-bubble smoking. Saudi Med J. 2002;23(8):953–958. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Rastam S, et al. The tobacco epidemic in Syria. Tob Control. 2006;15 suppl 1:24–29. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shafagoj YA, Mohammed FI, Hadidi KA. Hubble-bubble (water pipe) smoking: levels of nicotine and cotinine in plasma, saliva and urine. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40(6):249–255. doi: 10.5414/cpp40249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neergaard J, Singh P, Job J, Montgomery S. Waterpipe smoking and nicotine exposure: a review of the current evidence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(10):987–994. doi: 10.1080/14622200701591591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Factors related to frequency of narghile (waterpipe) use: the first insights on tobacco dependence in narghile users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76(1):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabbour S, El-Roueiheb Z, Sibai AM. Narghile (water-pipe) smoking and incident coronary heart disease: a case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:570. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knishkowy B, Amitai Y. Water-pipe (narghile) smoking: an emerging health risk behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2173. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/116/1/e113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hookah cafes on the rise. [Accessed December 15, 2008];Smokeshop Magazine. 2004 April; Available at: www.smokeshopmag.com/0404/retail.htm.

- 14.Lewin T. Collegians smoking hookahs filled with tobacco. New York Times. 2006 April 19; [Google Scholar]

- 15.Primack BA, Aronson JD, Agarwal AA. An old custom, a new threat to tobacco control. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(8):1339. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SY, Curbow B, Stillman FA. Harm perception of nicotine products in college freshmen. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(9):977–982. doi: 10.1080/14622200701540796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eissenberg T, Ward KD, Smith-Simone S, Maziak W. Water-pipe tobacco smoking on a U.S. college campus: prevalence and correlates. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42(5):526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among U.S. university students. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Roueiheb Z, Tamim H, Kanj M, Jabbour S, Alayan I, Musharrafieh U. Cigarette and waterpipe smoking among Lebanese adolescents, a cross-sectional study, 2003–2004. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):309–314. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varsano S, Ganz I, Eldor N, Garenkin M. Water-pipe tobacco smoking among school children in Israel: frequencies, habits, and attitudes. Harefuah. 2003;142(11):736–741. 807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weglicki LS, Templin T, Hammad A, et al. Health issues in the Arab American community. Tobacco use patterns among high school students: do Arab American youth differ? Ethn Dis. 2007;17(2 suppl 3):S3–22–S3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arizona Department of Education. Phoenix, AZ: Arizona Department of Education; Arizona Student Health Survey 2005 Methodology/Technical Report. 2005 July;

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PC Sample/PC School: Survey TA Sampling Software. 2000

- 24.McCabe SE, Teter CJ, Boyd CJ. The use, misuse and diversion of prescription stimulants among middle and high school students. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39(7):1095–1116. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. New York, NY: Columbia University; Malignant Neglect: Substance Abuse and America’s Schools. 2001

- 26.Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):393–398. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chattopadhyay A. Emperor Akbar as a healer and his eminent physicians. Bull Indian Inst Hist Med Hyderabad. 2000;30(2):151–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2006;55(5):1–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rice VH, Weglicki LS, Templin T, Hammad A, Jamil H, Kulwicki A. Predictors of Arab American adolescent tobacco use. Merrill Palmer Q (Wayne State Univ Press) 2006;52(2):327–342. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2006.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cobb CD, Glass GV. Ethnic segregation in Arizona charter schools education policy. [Accessed December 15, 2008];Anal Arch. 1999 7(1) Available at: http://epaa.asu.edu/epaa/v7n1/

- 31.Adelman WP. Tobacco use cessation for adolescents. Adolesc Med Clin. 2006;17(3):697–717. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2006.06.013. abstract xii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]