Abstract

TADB (http://bioinfo-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/TADB/) is an integrated database that provides comprehensive information about Type 2 toxin–antitoxin (TA) loci, genetic features that are richly distributed throughout bacterial and archaeal genomes. Two-gene and much less frequently three-gene Type 2 TA loci code for cognate partners that have been hypothesized or demonstrated to play key roles in stress response, bacterial physiology and stabilization of horizontally acquired genetic elements. TADB offers a unique compilation of both predicted and experimentally supported Type 2 TA loci-relevant data and currently contains 10 753 Type 2 TA gene pairs identified within 1240 prokaryotic genomes, and details of over 240 directly relevant scientific publications. A broad range of similarity search, sequence alignment, genome context browser and phylogenetic tools are readily accessible via TADB. We propose that TADB will facilitate efficient, multi-disciplinary and innovative exploration of the bacteria and archaea Type 2 TA space, better defining presently recognized TA-related phenomena and potentially even leading to yet-to-be envisaged frontiers. The TADB database, envisaged as a one-stop shop for Type 2 TA-related research, will be maintained, updated and improved regularly to ensure its ongoing maximum utility to the research community.

INTRODUCTION

Bacterial and archaeal toxin–antitoxin (TA) loci, typically containing two but occasionally three tandem genes, code for cognate partners that have been hypothesized or demonstrated to play key roles in stress response, bacterial physiology and stabilization of horizontally acquired genetic elements (1,2). The toxin genes invariably code for proteins, while matching antitoxin genes code for either antisense RNA or antitoxin proteins, resulting in classification as Type 1 or Type 2 TA loci, respectively. To date numerous phylogenetically and functionally distinct Type 2 TA systems have been identified through experimental and bioinformatics studies. In particular, since the advent of the genomics era it has become abundantly clear that Type 2 TA loci are richly distributed throughout the genomes of almost all free-living bacteria and archaea (3–7). Individual bacterial and archael genomes may harbor between 0 and >50 TA loci, with the vast majority encoding at least one TA locus. Consistent with the focus of this study, all further references within this report to ‘TA’ loci/genes/proteins refer solely to corresponding counterparts in ‘Type 2 TA’ systems.

TA toxin genes code for stable toxins that target either DNA replication or translation and these toxins are neutralized by short-lived protein antitoxins. As a general model for TA systems, the short-lived nature of the antitoxin ensures that cells which lose a TA locus and thus no longer produce the cognate ‘immunity’ antitoxin protein become susceptible to the stable toxin that has outlived the presence of its coding gene, resulting in toxin-mediated killing of the cell (2). Hence, prokaryotic organisms harboring TA loci are considered by some investigators to be ‘addicted’ to their native repertoire of TA loci. When present on plasmids and other horizontally acquired elements, TA systems are frequently viewed as ‘selfish DNA’ as many of these addiction systems have been shown to promote post-segregational killing of cells that have lost TA-encoding mobile genetic elements (8). A few TA loci have also been shown to confer within-host competitive advantage of the TA-encoding plasmid against other host permissive plasmids (9). In addition, chromosomally encoded TA pairs have also been shown or postulated to play multiple other functions. These systems can act to stabilize large horizontally acquired chromosomal regions, such as integrons, by selecting against their loss (10). TA pairs also provide immunity to the host cell from the same or related toxin encoded on other co-resident mobile genetic elements, thus acting as anti-addiction modules by allowing for the loss of one or more ‘redundant’ anti-toxin gene and its carrier mobile genetic element (2,11). A major area of active research in the TA field relates to a postulated regulatory role in bacterial stress physiology and the formation of dormant or ‘persister’ cells. Persister cells are involved in antibiotic resistance and pathogenicity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and several other important human pathogens (2,12). In Escherichia coli, persister cells can be formed by fluctuations in the expression of the HipA toxin, encoded by the hipBA TA tandem genes (13,14). Expression of HipA over a certain threshold in small numbers of cells causes dormancy (14). This subset of dormant cells is able to survive antibiotics that are active against growing cells, thus allowing the infecting organism to survive an antimicrobial assault and regenerate in time from a small number of surviving persister cells. Thus TA systems may well contribute towards stochastic variation within the population, gearing up individual subsets of organisms distinctly to favor survival of the population itself in the face of a likely wide diversity of unpredictable environmental, competitive and hostile challenges ahead.

Given the dramatic pace of expansion in experimental and bioinformatics data pertaining to TA systems in the last 10 years and the likely impending avalanche triggered by next-generation sequencing-facilitated prokaryotic- and metagenomic-sequencing projects, we have created a PostgreSQL database of Type 2 TA systems, known as TADB (http://bioinfo-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/TADB/), that provides for ready access, analysis, manipulation and exploitation of this invaluable biological information. We propose that TADB should serve as a ‘one-stop-shop’ for all Type 2 TA data sets and resources and are confident that in time it will facilitate efficient, multi-disciplinary and innovative exploration of the bacteria and archaea TA space, further defining presently recognized phenomena and potentially even leading to yet-to-be envisaged frontiers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

As of 30 July 2010, TADB contains 10 753 type 2 TA gene pairs identified within 1240 genome sequences representative of 962 strains of phylogenetically diverse bacteria and archaea. The data in TADB are derived from computationally predicted data sets and/or reports of experimentally validated TA genes. The BLASTP-identified 921 TA loci present in 147 sequenced genomes reported by Gerdes and co-workers (3,7) were first uploaded and classified into eight TA families. Next, the 5806 TA loci found in 604 genomes which had been assigned to 44 conserved TA domain pairs by Makarova et al. (4) were archived in TADB. The database was then further complemented with the data set of RASTA-Bacteria predicted TA loci identified in 883 annotated genomes. The RASTA-Bacteria algorithm utilizes RPSBLAST search and typical characteristics of TA loci, such as a two-gene, co-directed module coding for small proteins, to identify TA hits (6). RASTA-Bacteria TA pair hits with one score >70% and the other >60% were recorded by TADB, this strict cut-off yields broadly reliable TA candidates (6). Subsequently, the three data sets mentioned above were compared to ensure that only de-duplicated entries were included in TADB; identical TA loci from identical strains were eliminated.

In addition, we have identified further examples of known or putative TA loci by searching PubMed using the search terms ‘toxin AND antitoxin’ and manually inspecting all PubMed hits. Supplementary TA loci identified by this literature search strategy included six TA pairs, absent from the first three data sets mentioned above, in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (NC_000962) that had recently been (12). At present, TADB contains details of 106 experimentally validated TA loci. Significantly, text mining has identified a further three TA families and three three-component TA families that belong to more recently identified TA families that would not be detected by the current version of RASTA-Bacteria. Our TADB database now includes members of 11 two-component and 3 three-component TA families. These TA families were classified based on toxin protein sequence similarity and tertiary structure, as described in the reviews by Gerdes et al. (1) and Van Melderen and Saavedra De Bast (2) (See http://bioinfo-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/TADB/Introduction.html for more details). We have also classified TADB entries by a second classification system based on identification of TA pairs sharing cognate TA domains and independent of wider protein-level similarity as suggested recently by Makarova et al. (4), yet again offering the potential for future enhanced genome data mining and further expansion of the TADB database. TADB is expected to grow dramatically given next-generation sequencing-facilitated rapid acceleration in prokaryote-focused whole genome sequencing projects. As more information about the TA loci becomes available, the database will be expanded and improved accordingly.

TADB is implemented as a PostgreSQL relational database. The ontology-based Chado schema (15) was employed to house annotations and sequences of ∼1000 prokaryotic genomes which had been downloaded from the NCBI Refseq archive (16). A second customized schema was designed to organize the available experimental and in silico analyses data and references relating to TA loci reported in the literatures. TADB runs on a Linux platform with the Apache web-server. Web interfaces were developed using HTML, CSS and JavaScript. The majority of data pipelines were developed with PHP and Perl. In addition, the following freely available components were employed: (i) genome browser Gbrowse (17); (ii) circular genome visualization tool CGview (18); (iii) multiple sequence alignment and visualization tools, MUSCLE (19) and Jalview (20); (iv) primer design tool Primer3Plus (21); (v) IslandViewer (database of genomic islands) (22); (vi) dndDB (database of DNA backbone phosphorothioation) (23); (vii) ACLAME database (A CLAssification of genetic Mobile Elements) (24); (viii) GOLD database of genome sequencing projects (25).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

TADB provides a flexible and biologist-friendly web-interface. It allows users to view an entire genome’s TA locus repertoire, color coded by TA classification, within the context of the whole replicon and to access individual pages dedicated to each TA locus pair, toxin and antitoxin as required. The TADB homepage contains the following interfaces: ‘Home’, ‘Browse’ (browse by organism, TA family or TA conserved domains), ‘Search’ (search by species, TA family, gene or protein), ‘Tools’ (gene/protein sequence BLAST against TADB), ‘Download’ (TA gene/protein sequences), ‘References’ (literatures relating to TA loci), ‘Introduction’ (description of the toxin protein-based TA family classification system and the TA domain pair-based classification system), ‘Submission’ (report new TA loci to TADB), ‘Links’ and ‘Contact’.

TADB browse module

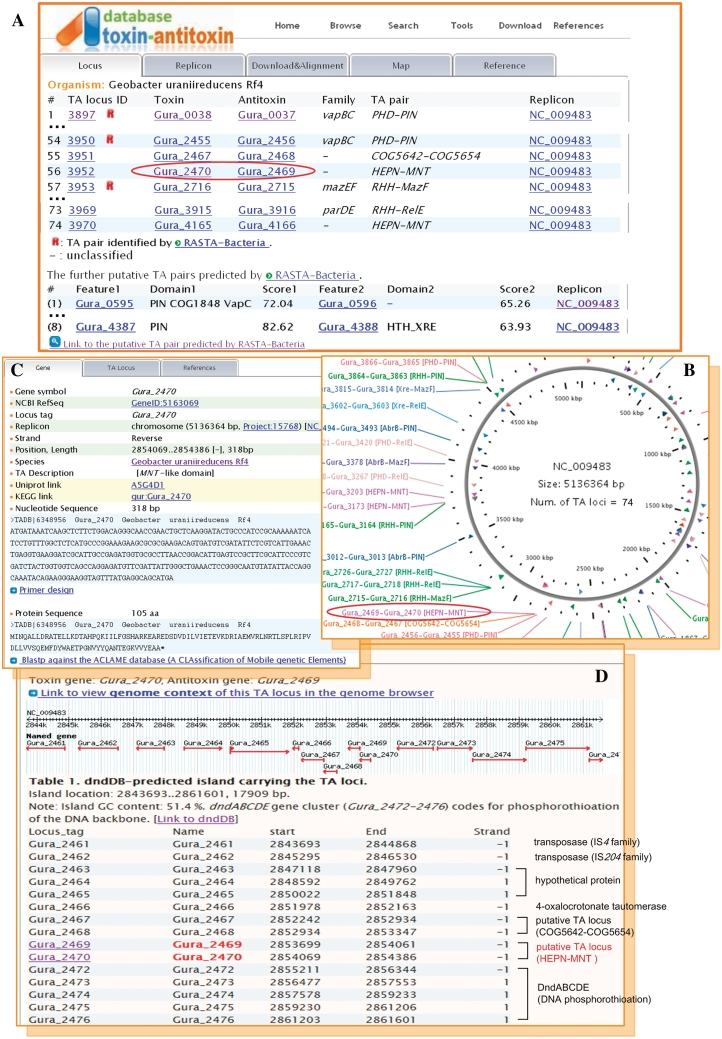

At the heart of TADB is the ‘Browse by organism’ page that provides a hyperlinked organized catalog of over 900 prokaryotic genomes with TA systems identified by one of the above-mentioned strategies. TADB allows the users to view genomic maps flagged by hyperlinked TA loci color-coded by TA family to provide a genome-scale view TA locus repertoires. In addition, users can access individual pages dedicated to each TA locus pair, toxin and antitoxin as required. As an example, TA loci in Geobacter uraniireducens Rf4 (NCBI Refseq accession no. NC_009483) were analysed (Figure 1). Geobacter uraniireducens Rf4 is a Gram negative Delta Proteobacteria which can reduce uranium using acetate and other organic acids (Supplementary Figure S3C). Recently G. uraniireducens has been used experimentally in bioremediation of metal-contaminated subsurface environments (26). Tabulated (Figure 1A) and graphically displayed (Figure 1B) outputs of the 74 putative TA pairs with conserved TA domains (4) in G. uraniireducens Rf4 are as shown. In addition, a further eight putative TA loci predicted by RASTA-Bacteria (6) are also included in these outputs. The genomic context of a selected TA locus is readily investigated further by using Gbrowse, as shown for the putative TA locus Gura_2469–Gura_2470 (Figure 1D). The putative toxin protein (yet to be experimentally characterized), Gura_2470, contains a MNT (minimal nucleotidyltransferase) domain, while its cognate putative antitoxin, Gura_2469, harbors a HEPN (higher eukaryotes and prokaryotes nucleotide-binding) domain (Supplementary Figure S3D) (4). Equivalent domain-level data are available for 12 other G. uraniireducens Rf4 putative TA pairs archived within TADB (Supplementary Figure S3). Interestingly, a second putative TA pair Gura_2467–Gura_2468 (4) is located a short distance upstream of the Gura_2469–Gura_2470 TA pair. This second toxin, Gura_2467, contains a RES domain (COG5654), which contains three highly conserved polar groups (arginine, glutamate and serine) that could form an active site. Its matching antitoxin, Gura_2468, contains an Xre family HTH (helix-turn-helix) domain (COG5642). Remarkably, the two tandem putative TA loci are located within a single 18-kb dnd island, details of which are archived within dndDB (Figure 1D) (23). Based on available data, the G. uraniireducens Rf4 dnd gene cluster (Gura_2472–2476) is likely to code for enzymes required for sequence-specific phosphorothioation of the DNA backbone (27). Consistent with a foreign origin, this 18-kb dnd island exhibits a lower G+C content (51%) than the genome average (54%) and codes for two likely transposase proteins (Gura_2461 and Gura_2462). Gura_2466, one of the island borne genes that lies close to the two TA loci, codes for an unusual 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase. This protein possesses one of the smallest enzyme subunits known (28). Bacteria belonging to the Geobacter genus are often the predominant species in a wide diversity of subsurface sediments under metal-reducing conditions (29). Given the abundance of phylogenetically diverse and functionally distinct TA loci within G. uraniireducens Rf4, it would be tempting to speculate that cumulative acquisition of TA loci and/or associated physically-linked mobile genetic DNA directly contributed to the environmental success and hardiness of Geobacter.

Figure 1.

An overview of TADB data sets and outputs using the G. uraniireducens Rf4 (NC_009483) TA locus-rich genome as an example. (A) A selected sample of the 74 TA domain pairs identified in this organism by Makarova et al. (4), plus another eight putative TA pairs predicted by RASTA-Bacteria (6) alone. (B) A segment of the circular genome map of G. uraniireducens Rf4 generated using CGview (18) showing TA loci in color code by TA family and TA domain pair. (C) A partial view of the features and sequence of the putative toxin gene Gura_2470 as shown by TADB. Hyperlinks to NCBI Refseq Project, UniProtKB, PDB and/or KEGG are provided. An integrated version of Primer3Plus (21) is available to facilitate design of PCR primers and selected TADB items can be searched against the ACLAME database of mobile genetic elements (24) using Blast via a single link. (D) A schematic view of the wider genomic context of the putative TA locus Gura_2469-Gura_2470 using Gbrowse (17). See text for details of the utility TADB-facilitated localized genome browsing strategy as highlighted by the example of the Gura_2469-Gura_2470 locus.

Using the ‘Browse by TA family’ link (Supplementary Figure S1), users can retrieve the full list of 11 two-component and 3 three-component TA families that encompass the full set of current TADB entries that have to date been mapped to a specific family (Supplementary Figure S2). The TA family classification system used is based on that described in the reviews by Gerdes et al. (1) and Van Melderen and Saavedra De Bast (2). As of now, 949 TA loci in 159 genomes have been assigned into these 14 TA families. Similarly, via the ‘Browse by TA related domain’ link (Supplementary Figure S3), the 5806 TA loci found in 604 genomes reported by Makarova et al. (4) have been organized into the 44 TA domain pair groupings.

TADB search options and tools

TADB offers several search tools with varied options. Through the ‘Search’ page, users can retrieve a specific object(s) in the TADB database by the following categories: species or genus, TA family, gene or protein. Via the ‘Tools’ page, users are able to blast a query sequence using WU-BLAST 2.0 (W. Gish, personal communication) against TADB to find and visualize potential homologous matches. A NCBI RPSBLAST (Reverse PSI-BLAST) (30) interface that relies on a position specific scoring matrix to identify potential toxin or antitoxin domains in a user-supplied protein sequence is also provided.

TADB reference module

The TADB reference section provides publication details of papers relating to TA systems that have been identified by text mining the NCBI PubMed database. Direct links to matching PubMed entries are also offered. At present this resource contains records of over 240 directly relevant scientific publications. This reference collection will be updated on a monthly basis with new entries being subject to subsequent manual curation and organization in a timely manner. The TADB reference collection has been sorted by the following headings: experimental studies, in silico analysis, protein structure data (Supplementary Figure S2C). TADB links the reviewed literatures to relevant TA loci, TA family, toxin domain, antitoxin domain and species pages as indicated by the corresponding thumbnail icons. The TADB reference collection is also searchable by TA family, author, title, journal, year, PubMed ID and matching abstracts can be subjected to standard word searches. This provides an easily accessible literature resource that has been subjected to both text mining and manual curation.

Future directions

As future developments, we will shortly be updating the records of experimentally verified TA loci with more functional information such as details of toxin targets, mechanisms of action of antitoxins, promoter, Shine–Dalgarno, terminator and identified TA loci regulators. Comparative analysis tool will also be incorporated into TADB to facilitate large scale synteny mapping of chromosomally encoded TA loci and their associated genomic islands. We are also exploring a pipeline, including the use of RPSBLAST, to implement automated searches of annotated or unannotated genome sequences for presently undiscovered potential members of the TADB-recorded families.

CONCLUSION

We envisage an evolving resource that maintains a growing variety of TA loci related data extracted and curated from experimental literature, submitted directly by users and derived by increasingly sophisticated bioinformatics analyses of bacterial and archaeal DNA, RNA and protein sequences. The increasing abundance of omics data will undoubtedly drive major growth of TADB. A broad range of similarity search, sequence alignment, genome context browser and phylogenetic tools are readily accessible to allow for user-directed interrogation of the database, examination of user-supplied sequences and other individualized directions of research. We propose that a unified resource such as TADB will facilitate efficient, multidisciplinary and innovative investigation of a wide range of aspects relating to prokaryotic TA systems. Studies of this nature are undoubtedly of major interest to many researchers given the complex genetic, evolutionary, biochemical, physiological and cellular processes frequently at the heart of operations of chromosome- and plasmid-encoded TA systems in diverse host organisms.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Natural Science Foundation of China; the 973 program, Ministry of Science and Technology of China; a Royal Society—National Natural Science Foundation of China International Joint Project grant 2007/R3 (to K.R. and Z.D.); the Chen Xing Young Scholars Programme, Shanghai Jiaotong University (to H.-Y.O.); an Action Medical Research grant SP4255 (to K.R.); E.M.H.’s post was part-funded by an Innovation Fellowship; East Midlands Development Agency grant (to K.R.). Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to two anonymous referees for their constructive suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gerdes K, Christensen SK, Lobner-Olesen A. Prokaryotic toxin-antitoxin stress response loci. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Melderen L, Saavedra De Bast M. Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: more than selfish entities? PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandey DP, Gerdes K. Toxin-antitoxin loci are highly abundant in free-living but lost from host-associated prokaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:966–976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Comprehensive comparative-genomic analysis of Type 2 toxin-antitoxin systems and related mobile stress response systems in prokaryotes. Biol. Direct. 2009;4:19. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guglielmini J, Szpirer C, Milinkovitch MC. Automated discovery and phylogenetic analysis of new toxin-antitoxin systems. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sevin EW, Barloy-Hubler F. RASTA-Bacteria: a web-based tool for identifying toxin-antitoxin loci in prokaryotes. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R155. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jorgensen MG, Pandey DP, Jaskolska M, Gerdes K. HicA of Escherichia coli defines a novel family of translation-independent mRNA interferases in bacteria and archaea. J. Bacteriol. 2009;191:1191–1199. doi: 10.1128/JB.01013-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wozniak RA, Waldor MK. A toxin-antitoxin system promotes the maintenance of an integrative conjugative element. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000439. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper TF, Paixao T, Heinemann JA. Within-host competition selects for plasmid-encoded toxin-antitoxin systems. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010;277:3149–3155. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szekeres S, Dauti M, Wilde C, Mazel D, Rowe-Magnus DA. Chromosomal toxin-antitoxin loci can diminish large-scale genome reductions in the absence of selection. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;63:1588–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saavedra De Bast M, Mine N, Van Melderen L. Chromosomal toxin-antitoxin systems may act as antiaddiction modules. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190:4603–4609. doi: 10.1128/JB.00357-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramage HR, Connolly LE, Cox JS. Comprehensive functional analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis toxin-antitoxin systems: implications for pathogenesis, stress responses, and evolution. PLoS Genetics. 2009;5:e1000767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moyed HS, Bertrand KP. hipA, a newly recognized gene of Escherichia coli K-12 that affects frequency of persistence after inhibition of murein synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 1983;155:768–775. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.2.768-775.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotem E, Loinger A, Ronin I, Levin-Reisman I, Gabay C, Shoresh N, Biham O, Balaban NQ. Regulation of phenotypic variability by a threshold-based mechanism underlies bacterial persistence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:12541–12546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004333107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mungall CJ, Emmert DB. A Chado case study: an ontology-based modular schema for representing genome-associated biological information. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:i337–i346. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, Dicuccio M, Federhen S, et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D5–D16. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein LD, Mungall C, Shu S, Caudy M, Mangone M, Day A, Nickerson E, Stajich JE, Harris TW, Arva A, et al. The generic genome browser: a building block for a model organism system database. Genome Res. 2002;12:1599–1610. doi: 10.1101/gr.403602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stothard P, Wishart DS. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:537–539. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterhouse AM, Procter JB, Martin DM, Clamp M, Barton GJ. Jalview version 2–a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Untergasser A, Nijveen H, Rao X, Bisseling T, Geurts R, Leunissen JA. Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W71–W74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langille MG, Brinkman FS. IslandViewer: an integrated interface for computational identification and visualization of genomic islands. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:664–665. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ou HY, He X, Shao Y, Tai C, Rajakumar K, Deng Z. dndDB: a database focused on phosphorothioation of the DNA backbone. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leplae R, Lima-Mendez G, Toussaint A. ACLAME: a CLAssification of mobile genetic elements, update 2010. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D57–D61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liolios K, Chen IM, Mavromatis K, Tavernarakis N, Hugenholtz P, Markowitz VM, Kyrpides NC. The Genomes On Line Database (GOLD) in 2009: status of genomic and metagenomic projects and their associated metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D346–D354. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki Y, Kelly SD, Kemner KM, Banfield JF. Microbial populations stimulated for hexavalent uranium reduction in uranium mine sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:1337–1346. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1337-1346.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He X, Ou HY, Yu Q, Zhou X, Wu J, Liang J, Zhang W, Rajakumar K, Deng Z. Analysis of a genomic island housing genes for DNA S-modification system in Streptomyces lividans 66 and its counterparts in other distantly related bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65:1034–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen LH, Kenyon GL, Curtin F, Harayama S, Bembenek ME, Hajipour G, Whitman CP. 4-Oxalocrotonate tautomerase, an enzyme composed of 62 amino acid residues per monomer. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:17716–17721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lovley DR, Holmes DE, Nevin KP. Dissimilatory Fe(III) and Mn(IV) reduction. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2004;49:219–286. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(04)49005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]