Abstract

LocDB is a manually curated database with experimental annotations for the subcellular localizations of proteins in Homo sapiens (HS, human) and Arabidopsis thaliana (AT, thale cress). Currently, it contains entries for 19 604 UniProt proteins (HS: 13 342; AT: 6262). Each database entry contains the experimentally derived localization in Gene Ontology (GO) terminology, the experimental annotation of localization, localization predictions by state-of-the-art methods and, where available, the type of experimental information. LocDB is searchable by keyword, protein name and subcellular compartment, as well as by identifiers from UniProt, Ensembl and TAIR resources. In comparison to other public databases, LocDB as a resource adds about 10 000 experimental localization annotations for HS proteins and ∼900 for AS proteins. Over 40% of the proteins in LocDB have multiple localization annotations providing a better platform for development of new multiple localization prediction methods with higher coverage and accuracy. Links to all referenced databases are provided. LocDB will be updated regularly by our group (available at: http://www.rostlab.org/services/locDB).

INTRODUCTION

Proteins are the fundamental functional components of the machinery of life. The particular cellular compartment, in which they reside, i.e. their native subcellular localization, is a key feature that characterizes their physiological functions. Many careful, hypothesis-driven experimental studies have been contributing to our large body of annotations of cellular compartments (1–5). Recently, high-throughput experiments have stepped up to the challenge to increase the amount of annotations (6–15). These data sets capture aspects of protein function and, more generally, of global cellular processes.

UniProt (release 2010_07) (16) constitutes the most comprehensive and, arguably, the most accurate resource with experimental annotations of subcellular localization. However, even this excellent resource remains incomplete for the proteomes from Homo sapiens (HS) and Arabidopsis thaliana (AT): of the 20 282 human proteins in Swiss-Prot (17), 14 502 have annotations of localization (72%), but for only 3720 (18%) these annotations are experimental. Similarly, of the 9099 AT proteins only 1495 (17%) have experimental annotations of localization. While LocDB stands on and roots UniProtKB, it encompasses this giant and adds specific value by collecting information about subcellular localization from the primary literature and from other databases. These data are enriched by annotations, links and predictions.

DATA SET

Curated entries with experimental data

LocDB contains experimental annotations for subcellular localization of 19 604 UniProt proteins; 13 342 of these are from Homo sapiens [10 102 Swiss-Prot and 3240 TrEMBL (17)] and 6262 from AT (3466 Swiss-Prot, 2796 TrEMBL). This raises the experimental annotations for human from 3720 (18%) to 13 342 (66%), and for thale cress from 1495 (16% of the UniProt subset of AT; note that this subset may constitute as little as 30% of all AT proteins) to 6262 (69% of the UniProt subset of AT). We classify all proteins according to the Gene Ontology (18) (GO) hierarchy into 12 primary classes of subcellular localization, i.e. use the following classes: cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, endosome, extracellular, Golgi apparatus, mitochondrion, nucleus, peroxisome, plasma membrane, plastid, vacuole and vesicles (Table 1). The proteins are further classified in subclasses of above primary classes denoted as secondary protein localizations, for example, protein RL21_HUMAN is experimentally annotated to be localized in primary: Nucleus and Secondary: Nucleolus.

Table 1.

Comparison between different localization annotation resourcesa

| Subcellular localization |

Homo sapiens |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LocDB | LOCATE | Uniprot (2010_07) | LocDB | SUBA II | Uniprot (2010_07) | |

| Cytoplasm | 4787 | 1054 | 1194 | 912 | 452 | 161 |

| Endoplasmic reticulum | 1027 | 367 | 185 | 292 | 285 | 52 |

| Endosome | 409 | 448 | 65 | 6 | 10 | 16 |

| Extracellular | 2266 | 380 | 33 | 188 | – | 8 |

| Golgi apparatus | 909 | 503 | 134 | 179 | 171 | 51 |

| Mitochondrion | 884 | 282 | 151 | 724 | 700 | 164 |

| Nucleus | 4560 | 2705 | 1181 | 1104 | 1031 | 326 |

| Peroxisome | 131 | 128 | 21 | 240 | 265 | 23 |

| Plasma membrane | 3940 | 1702 | 878 | 1835 | 3189 | 449 |

| Plastid incl. chloroplast | – | – | – | 2420 | 1945 | 267 |

| Vacuole | 297 | 250 | 34 | 862 | 849 | 35 |

| Vesicles | 258 | 99 | 34 | – | – | 1 |

Statistics

Each entry in LocDB has some experimental localization data. However, we have explicit annotations of a particular experiment type for only 25% of the entries. This is a work in progress as, curation is tedious and manual, and we are planning to update details regarding experiments with every new release of LocDB. Most annotations in LocDB are for the nucleus (20%), cytoplasm (20%) and the plasma membrane (20%). Almost two in three of all HS proteins are annotated in one of the largest three compartments (23% nucleus, 25% cytoplasm, 20% plasma membrane). Similarly, two in three of the AT proteins fall into one of the compartments (28% plastid (incl. chloroplast), 21% plasma membrane, 13% nucleus). The distribution of proteins within each region is accessible from the LocDB statistics page http://www.rostlab.org/services/locDB/statistics.php.

Multiple localizations

Many proteins travel, i.e. they stay in more than one subcellular localization at one point of their ‘life’. Most proteins annotated by traditional detailed biochemical experiments, point to one single compartment as the major native environment of each protein (19). By contrast, most high-throughput experiments identify most proteins in more than one compartment. Clearly, high-throughput experiments are noisy. Nevertheless, are noisy large-scale experiments closer to the truth than small-scale approaches? The answer remains unclear. About 40% of the LocDB entries have experimental evidence for more than one localization. This may imply that 60% of all proteins are primarily native to a single compartment. In fact, previous analyses suggest a similar value (19). However, this does not imply that only 40% of the proteins ever ‘travel through’ more than one compartment: many traveling proteins are likely not captured in the experimental data due to limited coverage and limitations in the experimental resolution (false negatives). On the other hand, some fraction of this 40% of proteins evidenced in several localizations may also indicate experimental errors (false positives). It remains unclear how to weigh those effects.

Most proteins unique

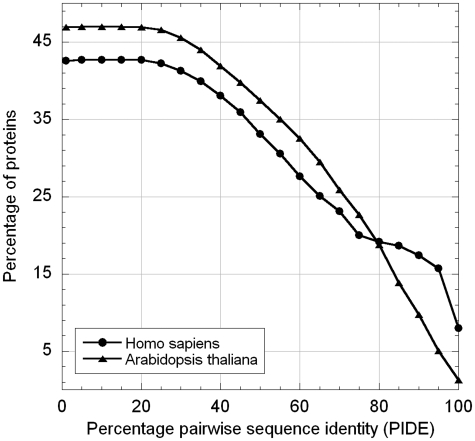

LocDB also clusters proteins into families or groups of related proteins (Figure 1). For instance, 1160 (8%) of all HS proteins and 74 (1%) of all AS proteins have more than 98 percentage pair wise sequence identity (PIDE) to another protein in the data set. Clustering at PIDE<25% yields 5587 proteins in HS (42%) and 2744 proteins in AS (47%). This implies that conversely about 7755 proteins annotated in HS and 3518 in AT are sequence-unique at the 25% PIDE threshold. The percentage of proteins with multiple localizations is higher when considering sequence-unique subsets, e.g. while 40% of all proteins are annotated with multiple localizations, 4.6% of those clustered at 98% PIDE and 45% of those clustered at 25% PIDE.

Figure 1.

Clustering of LocDB. We clustered the LocDB entries by BLASTclust (26) to explore whether or not some families are highly over-represented in LocDB, and found that they are not. For instance, 46% of HS and 43% of AT proteins in LocDB have levels of PIDE <25%, i.e. differ substantially in sequence. On the other end of the spectrum, only 8% of HS and 1% of AT proteins are very similar to each other (PIDE >98%). Note that levels of PIDE>70% usually suffice to infer similarity in localization at levels of about 75% (31), i.e. for over 80% of the LocDB entries no other entry could be used to predict localization by homology.

Experimental and predicted localization

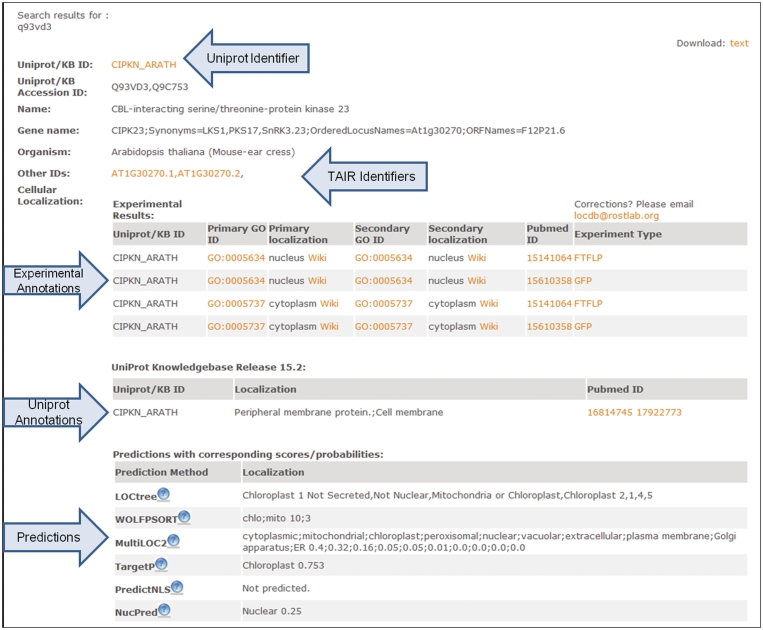

Each LocDB entry corresponds to one protein, and contains protein identifiers, experimental annotations of protein localization, types of experiments performed and the respective publication PubMed (20) identifiers, as well as predicted localization annotations from LOCtree (19), WOLFPSORT (21), MultiLoc (22), TargetP (23), PredictNLS (24) and Nucpred (25). Prediction results are given in both basic and detailed formats along with the respective reliability and probability scores (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Example for screen dump from LocDB. The example shows a search with the protein CIPKN_ARATH. Arrows highlight input, output and the distinction between different aspects of the output.

Data mining from primary literature

Data for LocDB are collected from reports of many low- and high-throughput experiments. Citations to the appropriate experiments are displayed on the LocDB protein entry pages. Protein sequences and identifiers from the experimental papers are extracted and BLASTed (26) against UniProt. The sequences with ≥98% PIDE over the entire sequence are assigned UniProt and Ensembl (27) identifiers for HS and TAIR (28) identifiers for AT.

Data mining from external databases

Data are also mined from external databases, e.g. LOCATE (1), SUBA (4) and many other resources. LocDB reports all the references with the entries in the database which link directly to their PubMed (20) abstracts.

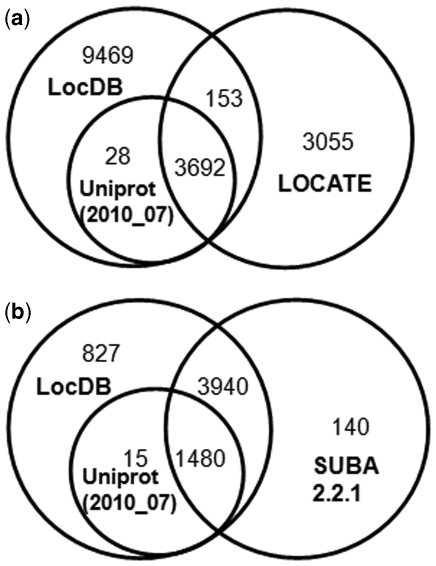

Comparison with other resources

Many excellent subcellular localization resources are available with experimental annotations of proteins for HT and AT such as LOCATE (1) for HT and SUBA (4) for AT. The comparison and overlap between these resources together with UniProt release (2010_07) are shown in Figure 3a and b. In addition, the comparison in number of proteins annotated in various compartments in these resources is shown in Table 1. These comparisons show that we have added ∼10 000 human protein localization annotations and ∼900 Arabidopsis protein localization annotations over LOCATE, SUBA and UniProt.

Figure 3.

Comparison between LocDB, UniProt, LOCATE and SUBA for experimental annotations of protein subcellular localizations. (a) The Venn diagram shows that LocDB has added annotations for 9469 HS proteins, not annotated in UniProt (2010_07) release (16) and LOCATE (1). (b) The Venn diagram shows that LocDB has added annotations for 827 AT proteins, not annotated in UniProt (2010_07) release (16) and SUBA (4).

As mentioned above, UniProt database contains both experimental and general annotations such as ‘Probable’, ‘By similarity’ and ‘Potential’ for protein subcellular locations. A very high level of discrepancies is found in the annotations for locations involved in secretory pathway such as Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum etc., especially in human proteins (shown in Figure 1a and b in Supplementary Data). In Arabidopsis, there is high discrepancy in all the compartments except nucleus and plastid. Comparison with databases DBSubLoc (29) and eSLDB (30) is also done; however, they are not shown as the annotations in these resources are mostly derived from Swiss-Prot database.

LocDB will be updated once every 3 months. There is also a provision for users to contribute to the resource by adding information on the contribution page of website as well as by sending an email to locdb@rostlab.org, if they come across any inaccuracies. We will use the database as a portal to access state-of-the-art prediction methods, which will enable users and developers to test prediction methods. We will also add predictions for proteins without experimental annotations that will be clearly marked as predictions. More eukaryotic and prokaryotic proteomes will be available in future through the database such as Escherichia coli and yeast. Moreover, we plan to add curated protein expression data and protein–protein interaction data in the following versions of locDB.

Availability

LocDB data can be retrieved as individual entries or downloaded as HTML and text files from http://www.rostlab.org/services/locDB. The database is a MySQL database and can be obtained upon request (locdb@rostlab.org) as an SQL file.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Funding for open access charge: The National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS; grant R01-GM079767) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are pleased to thank Amos Bairoch (SIB, Geneva), Rolf Apweiler (EBI, Hinxton), Phil Bourne (San Diego University) and their crew for maintaining excellent databases. Furthermore, thanks to all experimentalists who enabled this analysis by making their data publicly available.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sprenger J, Lynn Fink J, Karunaratne S, Hanson K, Hamilton NA, Teasdale RD. LOCATE: a mammalian protein subcellular localization database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D230–D233. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elstner M, Andreoli C, Klopstock T, Meitinger T, Prokisch H. The mitochondrial proteome database: MitoP2. Methods Enzymol. 2009;457:3–20. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)05001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keshava Prasad TS, Goel R, Kandasamy K, Keerthikumar S, Kumar S, Mathivanan S, Telikicherla D, Raju R, Shafreen B, Venugopal A, et al. Human Protein Reference Database – 2009 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D767–D772. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heazlewood JL, Verboom RE, Tonti-Filippini J, Small I, Millar AH. SUBA: the Arabidopsis subcellular database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D213–D218. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellaire G, Farrall R, Bickmore WA. The Nuclear Protein Database (NPD): sub-nuclear localisation and functional annotation of the nuclear proteome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:328–330. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunkley TP, Hester S, Shadforth IP, Runions J, Weimar T, Hanton SL, Griffin JL, Bessant C, Brandizzi F, Hawes C, et al. Mapping the Arabidopsis organelle proteome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:6518–6523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506958103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benschop JJ, Mohammed S, O'Flaherty M, Heck AJ, Slijper M, Menke FL. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of early elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1198–1214. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600429-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zybailov B, Rutschow H, Friso G, Rudella A, Emanuelsson O, Sun Q, van Wijk KJ. Sorting signals, N-terminal modifications and abundance of the chloroplast proteome. PLoS ONE. 2008;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001994. e1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaquinod M, Villiers F, Kieffer-Jaquinod S, Hugouvieux V, Bruley C, Garin J, Bourguignon J. A proteomics dissection of Arabidopsis thaliana vacuoles isolated from cell culture. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:394–412. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600250-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marmagne A, Ferro M, Meinnel T, Bruley C, Kuhn L, Garin J, Barbier-Brygoo H, Ephritikhine G. A high content in lipid-modified peripheral proteins and integral receptor kinases features in the arabidopsis plasma membrane proteome, Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1980–1996. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700099-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson NL, Polanski M, Pieper R, Gatlin T, Tirumalai RS, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Adkins JN, Pounds JG, Fagan R, et al. The human plasma proteome: a nonredundant list developed by combination of four separate sources. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:311–326. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300127-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo S, Jain M, Xie X, Sheth SA, Chang B, Goldberger OA, Spinazzola A, Zeviani M, Carr SA, Mootha VK. Systematic identification of human mitochondrial disease genes through integrative genomics. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:576–582. doi: 10.1038/ng1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung AK, Trinkle-Mulcahy L, Lam YW, Andersen JS, Mann M, Lamond AI. NOPdb: Nucleolar Proteome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D218–D220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheng S, Chen D, Van Eyk JE. Multidimensional liquid chromatography separation of intact proteins by chromatographic focusing and reversed phase of the human serum proteome: optimization and protein database. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:26–34. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500019-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gassmann R, Henzing AJ, Earnshaw WC. Novel components of human mitotic chromosomes identified by proteomic analysis of the chromosome scaffold fraction. Chromosoma. 2005;113:385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00412-004-0326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The UniProt Consortium. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) 2009. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D169–D174. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boeckmann B, Bairoch A, Apweiler R, Blatter MC, Estreicher A, Gasteiger E, Martin MJ, Michoud K, O'Donovan C, Phan I, et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:365–370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, Davis AP, Dolinski K, Dwight SS, Eppig JT, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair R, Rost B. Mimicking cellular sorting improves prediction of subcellular localization. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NLM. Free Web-based access to NLM databases. NLM Tech. Bull. 1997;296 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horton P, Park KJ, Obayashi T, Fujita N, Harada H, Adams-Collier CJ, Nakai K. WoLF PSORT: protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W585–W587. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoglund A, Donnes P, Blum T, Adolph HW, Kohlbacher O. MultiLoc: prediction of protein subcellular localization using N-terminal targeting sequences, sequence motifs and amino acid composition. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1158–1165. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Emanuelsson O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. Locating proteins in the cell using TargetP, SignalP and related tools. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:953–971. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cokol M, Nair R, Rost B. Finding nuclear localization signals. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:411–415. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brameier M, Krings A, MacCallum RM. NucPred – predicting nuclear localization of proteins. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1159–1160. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hubbard T, Barker D, Birney E, Cameron G, Chen Y, Clark L, Cox T, Cuff J, Curwen V, Down T, et al. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:38–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garcia-Hernandez M, Berardini TZ, Chen G, Crist D, Doyle A, Huala E, Knee E, Lambrecht M, Miller N, Mueller LA, et al. TAIR: a resource for integrated Arabidopsis data. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 2002;2:239–253. doi: 10.1007/s10142-002-0077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo T, Hua S, Ji X, Sun Z. DBSubLoc: database of protein subcellular localization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D122–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierleoni A, Martelli PL, Fariselli P, Casadio R. eSLDB: eukaryotic subcellular localization database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D208–D212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nair R, Rost B. Sequence conserved for subcellular localization. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2836–2847. doi: 10.1110/ps.0207402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]