Abstract

Inhibiting renal glucose transport is a potential pharmacologic approach to treat diabetes. The renal tubular sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) reabsorbs approximately 90% of the filtered glucose load. An animal model with sglt2 dysfunction could provide information regarding the potential long-term safety and efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors, which are currently under clinical investigation. Here, we describe Sweet Pee, a mouse model that carries a nonsense mutation in the Slc5a2 gene, which results in the loss of sglt2 protein function. The phenotype of Sweet Pee mutants was remarkably similar to patients with mutations in the Scl5a2 gene. The Sweet Pee mutants had improved glucose tolerance, higher urinary excretion of calcium and magnesium, and growth retardation. Renal physiologic studies demonstrated a prominent distal osmotic diuresis without enhanced natriuresis. Sweet Pee mutants did not exhibit increased KIM-1 or NGAL, markers of acute tubular injury. After induction of diabetes, Sweet Pee mice had better overall glycemic control than wild-type control mice, but had a higher risk for infection and an increased mortality rate (70% in homozygous mutants versus 10% in controls at 20 weeks). In summary, the Sweet Pee model allows study of the long-term benefits and risks associated with inhibition of SGLT2 for the management of diabetes. Our model suggests that inhibiting SGLT2 may improve glucose control but may confer increased risks for infection, malnutrition, volume contraction, and mortality.

More than 170 million people worldwide were suffering from diabetes in 2000 according to the World Health Organization (WHO), and >10% of the population aged 20 years and over in the United States are diabetic (The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, NIDDK, NIH). The prevalence of diabetes is projected to increase to an alarming figure of 366 million by 2030 worldwide. Diabetes is a common cause of health complications including macrovascular (myocardial infarction and stroke) and microvascular (nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy) disease, as well as enhanced risk for infections and death. In the face of this impending pandemic threat, however, the management of diabetes remains to be a major clinical challenge. Three recent landmark multicenter randomized clinical studies involving patients with type 2 diabetes including the Veterans Administration Diabetes Trial (VADT), the Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease (ADVANCE) trial, and the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) trial underscore the potential benefits of tight glycemic control in improving microvascular outcomes, yet these studies also highlighted an increased incidence of hypoglycemia and complications associated with aggressive management. Therefore, it is desirable to develop new therapies with high efficacy of lowering blood glucose yet a low propensity for side effects.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter (SGLT) inhibitors have been identified as a potential agent through their effect on renal glucose excretion. Two major SGLT transporters exist in the kidneys, SGLT1 and SGLT2, which differ in their affinity, substrate specificity, and tissue expression. Whereas SGLT1 is more widely expressed and is found in the small intestine, the distal (S2, S3) segments of the renal proximal tubule, and in cardiomyocytes,1,2 SGLT2 is expressed only in the apical brush border of the S1 and S2 portion of the proximal renal tubule. SGLT1 is a high-affinity (K0.5 = 0. 4 mM) low-capacity transporter and accounts for a small amount (10%) of reabsorption of filtered glucose in normal states1,3,4 and it does not discriminate between glucose or galactose. SGLT2 is a low-affinity (K0.5 = 2 mM) high-capacity transporter and is responsible for the majority (over 90%) of the filtered glucose reabsorbed.4,5

Familial renal glucosuria describes patients with a rare mutation in the solute carrier family 5, member 2 (SLC5A2) gene that encodes for a 75-kD sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2). Patients with this disorder manifest a variable degree of glucosuria, depending on the type of mutation and the number of alleles affected; massive glucosuria of 169 g/1.73 m2 per d has been reported,6 yet most of them remain euglycemic and have no other major health sequela.7 Given the apparent benign nature of loss of function of SGLT2 and its restricted renal expression, it follows that SGLT inhibition might be a valuable treatment for diabetes to enhance renal glucose excretion and thereby improve glycemic control.

Numerous SGLT inhibitors have been developed and are currently under investigation in the treatment of diabetic patients; they include Dapagliflozin, Canagliflozin, YM543, GSK189075, SAR7226, and ISIS 388626.5,8,9 Importantly, this class of agents will soon be made available for the management of type 2 diabetes. Because of the paucity of systematic follow-up and characterization of patients carrying SLC5A2 mutations, and a lack of animal models that target sglt2, the efficacy and safety of long-term inhibition of SGLT2 is yet to be established.

Here we report the generation, mapping, and characterization of a novel mouse mutant named Sweet Pee (SP) that carries a nonsense mutation in the Slc5a2 gene. To understand the effect of sglt2 inhibition on renal physiology, we determined urine flow, renal hemodynamics, and electrolyte excretion in homozygous, heterozygous, and control littermates. We show that, at baseline, sglt2 mutants manifest a distal osmotic diuresis with no change in proximal tubular water reabsorption. Mutants also exhibit slower growth with calcium, and magnesium wasting. At baseline, mutants have superior glucose tolerance but no difference in insulin sensitivity. Finally, we generated a diabetic cohort to determine the effect of impaired sglt2 function in a streptozotocin-induced (STZ-induced) model of diabetes. Although diabetic sglt2 mutants exhibit improved glycemic control, they have markedly higher overall mortality and occasional development of overwhelming urosepsis, suggesting that these therapies may be associated with significant adverse effects.

RESULTS

Generation and Identification of the Sweet Pee (SP) Mutants

In collaboration with the Centre for Modeling Human Disease (CMHD), we performed an autosomal dominant N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU) screen to identify mutations in genes responsible for renal phenotypes. ENU induces point mutations in the genomic DNA at a frequency of 1 × 10−3 per locus, which represents over a 100-fold greater than the estimated spontaneous mutation rate.10 Numerous ENU consortiums have been established internationally to generate novel mouse models for a variety of human diseases (refer to recent review by Soewarto et al.11). In this study, the high-throughput renal screen consisted of urinalysis of G1 offspring. ENU mutagenesis was performed on the C57BL6 background. One hundred fifty G1 mice were screened and we identified a single phenotypic variant, Sweet Pee, that exhibited isolated renal glucosuria with normoglycemia. Backcrossing this founder mutant with wild-type C3H strain generated litters to confirm heritability of the phenotype. Intermittent glucosuria was robust and heritable as a dominant trait, as it represented close to 100% penetrance in 50% of the G2's.

Genetic Mapping Studies

Rough mapping with genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers identified mouse chromosome 7 syntenic to human chromosome 16 as the region of interest (Supplementary Table 1 includes only partial data for illustration). The corresponding logarithm of odds score was >4 (Figure 1B), which strongly supports the presence of a quantitative trait locus. Further recombination from backcrossing mapped the critical region between 127 and 146 Mb (Figure 1A). Analysis of genes found within this interval pointed toward the solute carrier family 5 member 2, Slc5a2, as the candidate gene. Interestingly, the phenotype of the Sweet Pee mutants closely resembles the human genetic disorder of benign familial glucosuria due to mutations in SLC5A2.

Figure 1.

Mapping of renal glucosuria to mouse chromosome 7. (A) Recombination further narrows the critical region between SNPs rs3709679 and rs3716088. WT represents wild-type allele, Het represents heterozygous, and MT represents homozygous mutant allele at the specific SNP. (B) Chromosome 7 contains the critical region for the Sweet Pee mutation. The logarithm of odds scores were performed under the condition of a single quantitative trait locus genome scan, normal model assumption, binary phenotype, and inclusion of covariates by expectation-maximization algorithm.22,40

Establishing SLC5a2 To Be the Mutated Gene for Sweet Pee Mutants

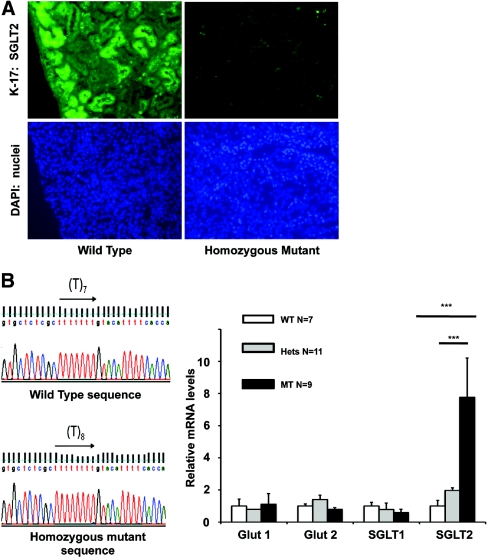

Slc5a2 is found in mouse chromosome 7 between 135 409 171 and 135 415 944. It consists of 14 exons. The transcript and translation lengths are 2277 bp and 674 residues, respectively. To confirm that this gene harbors the mutation that is underlying the phenotype in our SP mutants, we performed immunofluorescence assays with two separate sglt2 antibodies against both the N- and the C-terminus and observed no specific signal in the renal tubules of the homozygous mutants (Figure 2A, and data not shown) compared with normal signal in the wild type (WT).

Figure 2.

Expression of sglt2 is altered in Sweet Pee mutants. (A) Homozygous mutants demonstrated no sglt2 protein expression in the kidney: Immunofluorescence with goat polyclonal IgG antibody against the N-terminus (K17) of mouse sglt2 at ×20 magnification. (B) Sequencing revealed an insertion of a single Thymine in exon 4 at position 433. This mutation causes a frameshift and premature stop codon. (C) The Sweet Pee mutants showed a significant elevation of sglt2 mRNA expression in the renal cortex (***P < 0.001). No significant difference in glut1, glut2, and sglt1 between mutants and WT were detected. Data normalized to WT control. Housekeeping gene Hprt used as internal control. WT, wild type; Hets, heterozygous mutants; MT, homozygous mutants.

Genomic DNA isolated from the tails of six homozygous mutants and three WT mice were used for sequencing (refer to Materials and Methods for details). We discovered a mutation with an insertion of a single thymine at position 433 in exon 4. This 433insT frameshift mutation leads to the generation of a theoretical unique 73 amino acid neopeptide and a premature stop signal (Figure 2B). The mutation occurs in the fourth transmembrane helix, which is necessary for glucose translocation.12 Furthermore, such a mutation has been previously reported to result in a nonfunctional transporter in humans because of the deletion of the critical domains 10 through 13, which are crucial for substrate binding.12

Characterization of Sweet Pee Mutants

mRNA Expression of Glucose Transporters in the Renal Cortex.

Similar to patients with benign familial glucosuria, the SP mutants waste glucose in their urine because of inefficient reabsorption of the filtered glucose load. Interestingly, however, they are able to maintain a euglycemic state as confirmed with multiple random blood glucose sampling and identical hemoglobin A1C (HgbA1c) levels between mutant and WT mice. In addition to the expected changes in gluconeogenesis and cellular uptake of glucose, we speculate, in part, there might be a compensatory increase in glucose uptake through the distal sglt1 high-affinity low-capacity Na+ glucose cotransporter. This process might involve an increased number of sglt1 transporters that would depend upon an accelerated transcription of the Slc5a1 gene. However, mRNA measurement by quantitative PCR in the renal cortex of 7 WT, 11 heterozygous, and 9 homozygous mutant mice, with hypoxanthine phosphoribisyltransferase 1, Hprt, as the housekeeping gene, which is not regulated by changes in glucose (CT values for Hprt similar between WT and mutants), showed that mRNA levels for sglt1 were similar between genotypes (Figure 2C). As expected, no difference in the levels of glut 1 and glut 2 mRNA expression was found between the mutants and the WT mice. Surprisingly, the sglt2 mRNA levels were significantly upregulated, especially in the homozygous mutants, which showed an approximately eightfold increase compared with their WT littermates. Of note, the region amplified was proximal to the identified mutation. The sglt2 mRNA levels of the heterozygous mutants were approximately double those of their WT littermates. The above observation suggests that the expression of sglt2 is regulated, likely by the elevated glucose levels in the tubular filtrate.

Excretory and Hemodynamic Function in Sweet Pee Mutants Exhibit Calcium and Magnesium Wasting.

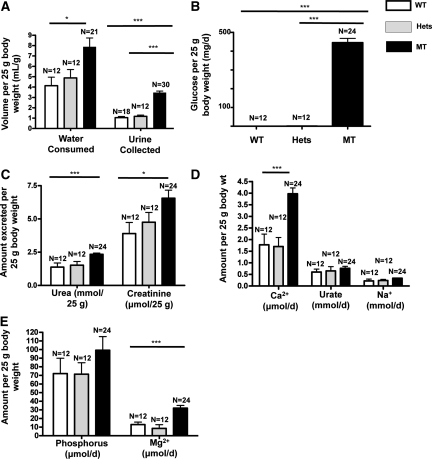

Given the degree of glucosuria in SP mutants, we wondered if there would also be a defect in proximal renal tubular reabsorption of fluid and electrolytes. To address these questions, we collected 24-hour urine samples from 18 WT, 12 heterozygous mutants, and 30 homozygous mutants. In addition, we carried out free flow micropuncture studies to directly measure proximal tubular reabsorption. As depicted in Figure 3A, homozygous mutants consumed more water and produced an approximately fourfold greater urine volume (P < 0.001). The amount of water intake was much greater than urine output, which is consistent with insensible loss as shown by others in mice.13 Even more dramatic is the 24-hour urinary glucose wasting. The average glucose excretion normalized to 25 g body wt was 0.34 and 0.85 in the WT and heterozygotes, respectively, compared with 445.3 mg/d in the homozygotes (P < 0.001) (Figure 3B). Homozygous mutants also had enhanced excretion of urea and creatinine (P < 0.05) (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Twenty-four hour urinary excretion of fluid and electrolytes varies in homozygous Sweet Pee mutants. Data normalized to 25 g body wt. (A) MT consumed more water and produced a significantly higher volume of urine output. (B) MT lost a massive amount (>400 mg) of glucose on a daily basis. In contrast, WT and Hets excreted only 0.3 and 0.8 mg/d. (C) MT had a significantly higher urinary urea and creatinine excretion per day compared with their heterozygous mutants and WT littermates. (D) MT excreted more calcium. No appreciable difference in urinary urate and sodium excretion. (E) MT lost significantly more magnesium. There was also a trend toward higher urinary phosphorous excretion in the MT. WT, wild type; Hets, heterozygous mutants; MT, homozygous mutants (*P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001).

As described previously, patients with benign familial glucosuria may present with loss of other micronutrients.6 Accordingly, we quantified urinary calcium, phosphorous, magnesium, and urate excretion (Figure 3, D and E). Urinary excretion of calcium and magnesium were both significantly increased in homozygous mutants compared with that of WT mice (P < 0.05). There was also a trend toward an increased phosphate excretion. Mutants also exhibited greater potassium output (24-hour excretion per 25 g body wt in mmol/d: 0.52 (WT), 0.57 (heterozygotes), and 0.76 (homozygotes); P < 0.05). However, no differences in urinary excretion of urate or sodium were detected. Finally, none of the mice had significant proteinuria. Unaltered urinary Na+ excretion is consistent with direct measurements of proximal tubular reabsorption that revealed comparable single-nephron GFRs (SNGFRs) and there were no major differences in absolute or fractional fluid reabsorption between WT and the homozygous mutants (% absorption: 46.4% and 43.9%, respectively; P = 0.7) (Table 1). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in whole kidney GFR determined by fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-inulin (GFR) in conscious mice as depicted in Table 1. The average GFR for WT and homozygous SP mutants was 522.8 and 460 μl/min (P = NS). Because SP mutants tend to have smaller kidneys, when corrected for kidney weight, the GFR for WT and homozygotes was identical (0.96 versus 0.97 μl min−1 mg−1, respectively; P = NS). In addition, mean arterial pressures were also not different between SP mutants and WT mice (85 and 89 mmHg, respectively). In conjunction with comparable plasma renin and serum hematocrit (Table 1) between the mutants and the WT control, our data suggest that, under normal conditions, loss of function in sglt2 does not have any significant effect on volume status as long as fluid consumption can be maintained (Figure 3A).

Table 1.

Sweet Pee mutants do not show signs of extravascular volume contraction under normal conditions

| Wild Type | SEM | n | MT Mutant | SEM | N | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (g) | 28.7 | 0.3 | 6 | 28.1 | 1.0 | 9 | 0.66 |

| Kidney weight (mg) | 563 | 14.8 | 4 | 481 | 14.1 | 7 | <0.005 |

| MAP | 89 | 3 | 4 | 85 | 2 | 5 | 0.5 |

| Uosmol (mosmol/L) | 2013 | 175 | 4 | 1596 | 44 | 6 | 0.02 |

| HCT (%) | 46.9 | 0.5 | 6 | 46.5 | 0.6 | 9 | 0.63 |

| GFR (μL/min) | 522.8 | 32.2 | 6 | 460 | 21.1 | 9 | 0.11 |

| SNGFR | 13.6 | 0.9 | 4 | 15.6 | 1.4 | 5 | 0.1 |

| Prox. Absorb. | 46.4 | 1.8 | 4 | 43.9 | 3.2 | 5 | 0.68 |

No difference in weight, mean arterial blood pressure (MAP), and Hematocrit (HCT). However, urine osmolarity (Uosmol) was significantly lower. GFR as well as single-nephron GFR (SNGFR) were similar between the mutants and the wild type. No difference in the percentage of proximal absorption (Prox. Absorb.) was observed.

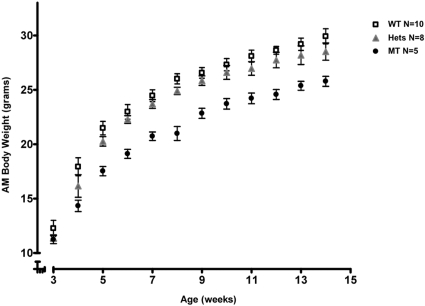

Growth Is Restricted in Sweet Pee Mutants.

As noted above, homozygous mutants exhibit greater urinary loss of glucose and some essential micronutrients. Accordingly, we followed the weight gain in 10 WT, 8 heterozygotes, and 15 homozygotes from 3 to 14 weeks of age. At each time point, body weights were significantly lower in the homozygous mutants. Weights were also reduced in the heterozygotes compared with WT mice (P = 0.001). Thus, it appears that the severity of growth restriction correlates with the number of alleles affected (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A decreased expression of Sglt2 is associated with growth retardation and the effect is dose-dependent. Homozygous mutants weighed significantly less at each time point compared with their heterozygous and WT littermates (****P < 0.0001). Heterozygotes also demonstrated less weight gained compared with WT (***P = 0.001). WT, wild type; Hets, heterozygous mutants; MT, homozygous mutants.

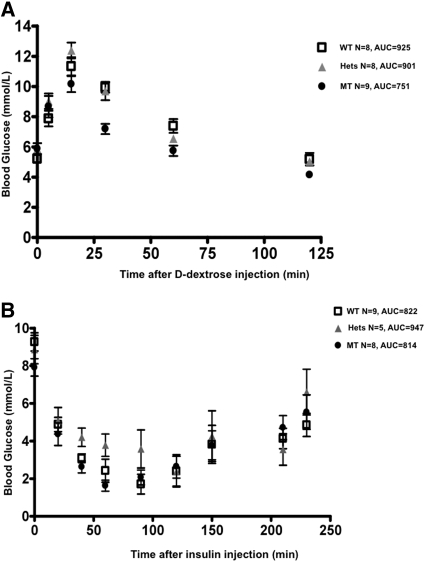

Sweet Pee Mutants Exhibit Improved Glucose Tolerance but No Change in Insulin Sensitivity.

Because the SP mutants exhibit dramatic glucosuria, we investigated whether inhibition of sglt2 affects glucose metabolism. A total of 8 WT, 8 heterozygous mutants, and 9 homozygous mutants were studied. As shown in Figure 5A, serum glucose levels peaked at 15 minutes, which is consistent with other studies reported in the literature.14 After administration of glucose, the average peak glucose value achieved was significantly lower in the homozygous mutants. Moreover, their blood glucose returned to baseline earlier than the heterozygous and the WT littermates.

Figure 5.

Sglt2 dysfunction results in better glucose tolerance without hypoglycemia. (A) Standard intraperitoneal d-dextrose challenge test: 1 mg/g body wt after a 14-hour fast. MT exhibited significantly lower glucose levels at the peak and the recovery phase (*P < 0.05). (B) Standard insulin tolerance test: insulin 2 units per kg body wt after a 6-hour fast. No difference in insulin sensitivity between the Sweet Pee mutants and WT mice. WT, wild type; Hets, heterozygous mutants; MT, homozygous mutants; AUC, area under the curve.

To further evaluate the mechanism(s) of the improved glucose tolerance in the SP mutants, we performed a standard insulin challenge test. Although one homozygous mutant and two WT mice developed significant hypoglycemia during the study, there was no difference in the response to insulin challenge between the mutants and the WT control (Figure 5B). Thus, inhibition of sglt2 function does not affect tissue sensitivity to insulin, and the observed superior glucose tolerance is likely due to enhanced glucosuria alone. Furthermore, mutants were not more susceptible to hypoglycemia compared with their WT littermates.

Sweet Pee Mutants Do Not Show Tubular Injury at Baseline.

The kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and the neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) are two well-validated biomarkers that are upregulated in the acute phase of kidney injuries in both humans and rodents. Given the persistent exposure to high luminal glucose concentrations and persistent osmotic diuresis, we wondered if the SP mutants, particularly the homozygotes, might exhibit tubular injury at baseline. As shown in Supplemental Figure 1, mRNA levels for NGAL in SP mutants were not elevated compared with those of the WT controls. Furthermore, random urine samples obtained from 8 adult WT, 4 adult heterozygous mutants, and 10 adult homozygous mutants for urinary KIM-1 analysis showed no increase in KIM-1 excretion among the mutant mice (Supplemental Figure 2).

Diabetic Sweet Pee Had Better Glucose Profile but Higher Mortality

Given the superior glucose tolerance at baseline, we speculated that the SP mutants might be protected from the development of diabetic complications. Therefore, we induced diabetes in SP male mutants and WT male controls with the low-dose streptozotocin (STZ) protocol. Only mice with persistent blood sugars >20 mmol/L were included in the analysis (7 diabetic WT, 12 diabetic heterozygotes, and 23 diabetic homozygotes). Notably, upon the first round of STZ injection, 86% of the WT, 93% of heterozygotes, and 52% of homozygous SP mutants became diabetic (P < 0.01) as defined by a random blood glucose level of ≥20 mmol/L. Nonresponding mice were reinjected according to a 5-day low-dose STZ protocol (one WT, one heterozygote, and nine MT). Of the 16 MT nonresponders, 9 were reinjected. Sweet Pee mutants had significantly attenuated levels of glycosylated hemoglobin (HgbA1C) measured at 16 weeks or older, from the time of STZ induction. As shown in Figure 6A, both mutants and WT mice had similar baseline HgbA1C of approximately 3%. This level is comparable to that reported in the literature for C3H/HeJ inbred mouse strain.15 However, no significant proteinuria was detected. The protein-to-creatinine ratios ±SEM at 21 weeks were 4.79 ± 1.4, 4.02 ± 1.08, and 4.18 ± 1.0 mg/mg for WT, heterozygotes, and MT, respectively (P = NS).

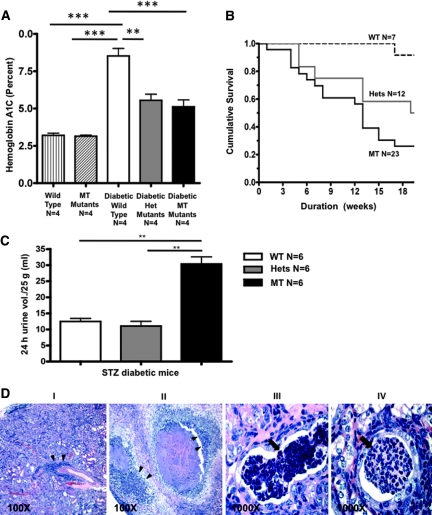

Figure 6.

Diabetic Sweet Pee demonstrates superior glycemic control but higher mortality. (A) The diabetic Sweet Pee mutants (both Hets and MT) had better glycemic control; they had significantly lower HgbA1C compared with diabetic WT mice. No difference in HgbA1C between nondiabetic homozygous mutants and wild type. As expected, diabetics had significantly higher average HgbA1C compared with the nondiabetics (P < 0.05). Blood samples were obtained from studied animals after >16 weeks from STZ injection. Diabetes was confirmed with random blood glucose >20 mmol/L. (One way ANOVA: **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.) (B) The diabetic Sweet Pee mutants exhibited significantly higher mortality compared with the diabetic WT mice (P < 0.05: Log rank test − χ2). Mice were followed from the date of low-dose STZ injection. (C) Diabetic homozygous Sweet Pee mutants exhibited dramatic 24-hour urine output. t test: **P < 0.01. (D) Severe pyelonephritis and sepsis in a diabetic Sweet Pee mutant. (I and II) At lower magnification, there was a significant leukocytic infiltration (double arrowhead), (II) showed dramatic necrotic kidney parenchyma; (III and IV) higher magnifications delineate tubular white blood cell casts (blocked arrow). Infections were not observed in diabetic WT mice or nondiabetic WT and mutants.

Despite the improvement in glycemic control, diabetic STZ-induced mutants with random serum glucose values >20 mmol/L exhibit a markedly higher mortality rate compared with diabetic WT mice. As illustrated in Figure 6B, <30% of the homozygous mutants survived to week 20 from the day of STZ induction, compared with 50% and 90% of the heterozygotes and the WT, respectively. Although the cause of death could not be determined for all of the mice, urinary tract infections were observed in a number of cases manifested as cloudy urine and detection of bacteria on gram stain among the diabetic homozygous and heterozygous cohorts (15% and 20%, respectively, versus none in WT: P = NS). Moreover, kidneys of these mice when harvested at a preterminal stage showed massive infiltration by polymorphonuclear white blood cells, together with parenchymal necrosis (Figure 6D). Furthermore, diabetic homozygous SP mutants excreted massive volumes of urine. As depicted in Figure 6C, an average 25-g mouse produced 29 ± 2.3 ml of urine per day, which is greater than its entire body weight. The degree of polyuria in the diabetic WT was significantly less; they excreted an average of 12.5 ml of urine per 24 hours (P < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Promoting urinary excretion of glucose is an emerging strategy for the management of type 2 diabetes. To this end, SGLT inhibitors are under investigation in 13 current clinical trials around the world. In the past, the utility of SGLT inhibitors such as phlorizin were limited because of their lack of selectivity for SGLT2.16 Because SGLT1 cotransporters are predominantly expressed in the brush border surface of the small intestine, nonselective SGLT inhibition leads to osmotic diarrhea and other intolerable gastrointestinal side effects in addition to glucose and galactose malabsorption. The compounds currently in clinical trials have much better selectivity toward SGLT2. In this study, we generated a mouse lacking sglt2 using ENU mutagenesis, which provides an excellent model system to study the effect of sglt2 inhibition in diabetic and nondiabetic states.

First, we showed that the genetic mutation that underlies the Sweet Pee phenotype is due to a single thymine insertion in exon 4 of the Slc5a2 gene. This mutation is predicted to result in a frameshift and a premature stop codon. Although ENU mutagenesis usually generates point mutations resulting in single base changes, insertion mutations have been reported previously.17,18 In fact, one- or two-base insertion mutation occurred up to 37% in one series.19 Both Western blotting (not shown) and immunofluorescence provided evidence that the sglt2 protein is not expressed in proximal tubules of Sweet Pee mutants. Moreover, our mutants behave similarly to patients with benign familial glucosuria, which arises as the result of loss of function SLC5A2 mutations. In contrast, at the mRNA level, we observed an upregulation of sglt2 expression in isolated renal cortex of the Sweet Pee mutants, suggesting that expression of sglt2 may be regulated, perhaps by the elevated tubular glucose levels. The real-time primers were designed to amplify a region proximal to the nonsense mutation, which was likely protected from endogenous nonsense-mediated mRNA decay.20–24

Similar to patients with mutations in both SLC5A2 alleles, homozygous Sweet Pee mutants exhibit dramatic glucosuria of >400 mg/d. Despite their remarkable glucosuria, mutants were normoglycemic and have similar HgbA1c as their WT littermates. The heterozygous mutants have a phenotype intermediate between WT and the homozygotes. There was no overt urinary sodium wasting, consistent with an analysis of proximal tubular reabsorption and renal hemodynamics that revealed only mild differences between mutants and WT mice, perhaps mediated by the epithelium sodium channel activated by a higher flow state. Importantly, proximal tubular fluid reabsorption was not affected by lack of sglt2 function. Finally, there was no evidence that persistent massive glucosuria results in acute tubular injury or stress as KIM-1 and NGAL levels were not elevated in homozygous mutants. The apparent benign nature of persistent glucosuria and the isolated distal osmotic diuresis that promotes free water loss without sodium wasting raises the intriguing possibility that these inhibitors might be a therapeutic option to treat conditions of water overload, such as the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone. Despite the absence of major differences in electrolyte excretion, the massive glucosuria was associated with an increased urinary excretion of calcium, magnesium, potassium, creatinine, and urea. The higher amount of calcium and magnesium loss in the urine may reflect an impaired voltage mediated absorption in the distal nephron secondary to a high-flow state.25,26 This is consistent with a distal nephron flow-mediated mechanism for the observed accentuated urinary potassium excretion among the homozygous SP mutants. Given the significant reduction in growth of mutants compared with that of WT, the safety of SGLT2 inhibition in diabetic children and the long-term effects on bone mineral metabolism in adults should be scrutinized. The observed significantly larger creatinine and urea output in the mutants while their GFR was comparable to that of the WT, together with a trend toward increased urinary phosphate excretion and a retardation to weight gain, suggest that these mice may well be in a catabolic state.27 We speculate that the heterozygous mutants may also be in a relative catabolic state to explain the observed lower weight gain. In the management of type 2 diabetes, induction of weight loss may be desirable. However, this effect on the nutritional status in special populations including those with end-stage renal failure will require further investigation.

The potential benefit of SGLT2 inhibition to lower blood glucose in diabetes is supported by our study. Sweet Pee mutants demonstrated better glucose tolerance, presumably related to renal glucose wasting because insulin sensitivity is unaffected. Furthermore, at baseline, sglt2 inhibition does not predispose to hypoglycemia or acute kidney injury. In turn, with diabetes, the mutants have improved glucose control including lower HgbA1c levels. Despite an improvement in metabolic control, this did not translate into a better overall clinical outcome among the Sweet Pee mutants. There was no observed difference in protein/creatinine ratios, although the C3H strain is relatively resistant to diabetic nephropathy. Moreover, mortality rate was significantly higher in diabetic Sweet Pee mutants that can be explained, at least in part, by increased risk of urosepsis. Future study with antibiotic administration will elucidate the effect of urosepsis on mortality. Interestingly, a pilot study of SGLT inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes also showed a predilection to genitourinary tract infections.28 More importantly, diabetic SP mutants, particularly the homozygotes, generate extremely large daily urine volumes that are comparable to their body weights. Failure to maintain adequate fluid intake to replace the urinary loss will result in severe intravascular volume contraction.

It is interesting that homozygotes appear more resistant to STZ-induced diabetes. Nine of 26 homozygotes required a second STZ induction compared with 1 in each of the other groups. Although the cumulative STZ dose was higher in those injected twice, statistical analysis of mortality differences in diabetic mice injected only once with STZ was similar to whole group analysis. None of the mice died within the first 2 weeks following reinjection. Taken together, the data suggest that mortality is not due to direct STZ toxicity, but the mechanism of STZ resistance requires further investigation.

In summary, we report here the generation of a novel sglt2 mouse mutant. This mutant represents a useful model for the study of SGLT2 inhibition in the treatment of diabetes. The short-term efficacy in better glucose control has been demonstrated in our diabetic mutants. Because SGLT inhibitors may lower BP, the effect on BP in STZ-induced diabetic mutants remains to be examined. Finally, our data point to the potential risks of using SGLT2 inhibitors for glycemic control in diabetes with respect to infection, malnutrition, and volume contraction and suggests that these areas should be carefully evaluated in patients receiving SGLT2 inhibitors.

CONCISE METHODS

Generation of Sweet Pee Mutant

Inbred mouse strains C57BL/6J (B6) and C3H/HeJ (C3H) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mutant Sweet Pee was generated on a genetic background of mutagenized B6 and WT C3H, as part of an ENU project in the Center for Modeling Human Disease (CMHD) for genome-wide mutagenesis, Toronto, Canada. ENU mutagenesis was performed as described previously.29 Mutant SP was identified on a dominant screen at week 6. A mutant breeding line was established by backcrossing this founder to WT C3H. The heritability of glucosuria was confirmed. Subsequent backcross that involved breeding between the newly identified SP mutant and the WT C3H/HeJ mice, as well as intercross between SP mutants were set up for mapping and further phenotypic characterization. The use of the mice in this study was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital Animal Care Committee, in accordance with the Ontario's Animals for Research Act, and the federal Canadian Council on Animal Care. All mice used in this study were male and maintained on standard rodent chow.

Mutation Mapping

A rough map was generated with Illumina genomewide SNP-based chip analysis, consisting of 891 SNP markers, and was performed at the Center for Applied Genomics (TCAG), the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. A total of 10 G2 mice exhibiting intermittent glucosuria from backcross breeding, 3 intercross mice with persistent high-grade (>55 mmol/L) glucosuria, and 3 G2 mice with no glucosuria were used. Fine mapping was provided fee-for-service by the TCAG.

Sequencing

Direct genomic sequencing using tail DNA was carried out to cover all of the exons and splice regions. Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse tails and purified as described previously.30 The insertion mutation identified in exon 4 was amplified with Platinum DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and the following PCR primers, which were designed on the basis of sequence information from the Mulan ECR browser: (Sense 5′-AAC CCA GGA AGG AGT GCT CTT GAC-3′, antisense 5′-ACC CAC AGC TTG GAG ACT TGC T-3′). The above primers produced a 2164-bp PCR product, which was then confirmed with agarose gel electrophoresis. The correct band was excised and purified with GeneClean kit (MP Biomedicals). The product was then sent to the TCAG sequencing facility using traditional Sanger chain termination method. The following nested primers were used to identify our mutation (a total of six homozygous mutants and three wild type were used for sequencing): (Sense 5′-AGG CAC TTC CGC TGT GTC TTC T-3′, antisense (for confirmation): 5′-CCA CAG CTT GGA GAC TTG CT-3′).

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from mouse tails30 and PCR was used to identify Sweet Pee mutants with the following primers to produce a 470-bp PCR product: (Sense 5′-TGT GAG GCT GTC CCA AGA ATG T-3′, antisense 5′-TCA GAG TCC CAG CAT TTG GTC T-3′). The PCR product was then digested with restriction enzyme TaqI (T↓CGA) Fast Digest (Fermentas) for 5 minutes at 65°C (wild type: two bands at 225 and 245 bp; heterozygous mutant: three bands at 225, 245, and 470 bp; homozygous mutant: one band at 470 bp).

Immunofluorescence

Freshly dissected kidneys were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C, treated with 30% sucrose at 4°C overnight, and then embedded with OCT for cryopreservation. The kidneys were then sectioned at 6 μm with a Cryostat. They were allowed to dry overnight. Nonspecific staining was minimized by incubating sections in 10% BSA blocking PBS buffer before the application of the primary antibody. The primary antibody was applied overnight at 4°C. The sections were then rinsed with PBS before incubating with a secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour in the dark. VECTASHIELD mounting medium with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for nuclear stain was added before applying cover slips and sealing with nail polish. The following primary antibodies and dilutions were used: K-17 and C-19 goat polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) anti-mouse sglt2 at 1:100 and 1:50, respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). FITC-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-goat IgG at 1:100 (Jackson Laboratories Inc.).

Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the renal cortex using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Ferments) and random hexamer primers (Fermentas) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA samples and standards were amplified in qPCR MasterMix Plus for SYBR Green I (BioRad). Samples were analyzed in triplicate. Relative quantification of target gene expression was evaluated using comparative CT method.31 The ΔCT value was determined by subtracting the Hprt CT value of each sample from its respective target CT. Fold changes in gene expression of the target gene were equivalent to 2−ΔΔCT. The following primers were used in the study: glut1 sense 5′-TCC GGT ATC GTC AAC ACG GCC T-3′, antisense 5′-AGC ACA GCA CAG CCT GCC AT-3′; glut2 sense 5′-CGG CTG TCT CTG TGC TGC TT-3′; antisense 5′-GCA GCA CAA GTC CCA CCG ACA T-3′; sglt1 sense 5′-GGA AGC ATA TGA CCT GTT CTG-3′, antisense 5′-GAC AGA GTG TCA GAC AAC AC-3′; sglt2 sense 5′-ATG CGC TCT TCG TGG TGC TG-3′, antisense 5′-ACC AAA GCG CTT GCG GAG GT-3′).

Twenty-Four Hour Urine Collection

Three mice of the same genotype were used for each 24-hour study. Two Nalgene metabolic cages were used simultaneously as paired experiments (matched for age and weight). Amount of water consumed was obtained on the basis of the difference between before and after study water-bottle weights. Similarly, urine output was estimated with the same strategy. The urine was centrifuged at 4°C for 10 minutes at 10,000 rpm. The urine samples were then flash frozen with liquid nitrogen before being sent to the hospital biochemistry laboratory (Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Canada). Automated Roche Modular (Roche Diagnostics) was the platform used for analysis.

Metabolic Tests

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Test.

Mice were maintained at a normal light/dark cycle and fasted for 14 hours with free access to water. Each conscious mouse then received an intraperitoneal injection of d-dextrose (1 mg/g body wt). Blood samples were collected from the tail at time 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes and were analyzed with the Bayer Contour blood glucose monitoring system.

Intraperitoneal Insulin Tolerance Test.

Mice were fasted for 6 hours with free access to water. Conscious mice then received an intraperitoneal injection of insulin (Linco Research, St. Charles) (1.2 units per kg body wt). Blood samples were collected at 0, 20, 40, 60, 90, 120, 150, 210, and 230 minutes when their blood glucose returned to baseline.

Streptozotocin Treatment.

For diabetes induction, mice were aged 3 to 4 weeks and received intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin (Sigma Life Science, Sigma-Aldrich) at a low-dose protocol of 50 mg/kg after a 4-hour fast for 5 consecutive days. The dosage was adjusted daily based on their daily weights. STZ was dissolved in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer pH 4.5 and was injected within 5 minutes of dissolution.

Hemoglobin A1C.

Diabetic mice were aged for at least 16 weeks before blood samples were collected with EDTA-Vaccu tubes. The tubes were immediately put on ice and HgbA1C assay performed with Siemens DCA System and read by Bayer DCA 2000-1 (Model 5031C).

Micropuncture Study, Invasive Mean Arterial BP Measurement, and Bladder Urine Collection for Analysis

The micropuncture methodologies were validated as described previously.32 To determine kidney GFR and nephron filtration and reabsorption rates, mice were infused with 125I iothalamate (Glofil; Questcor Pharmaceuticals, Hayward, CA) at about 40 μCi/h. End proximal segments were identified by injecting a bolus of artificial tubular fluid stained with FD&C green from a 3- to 4-μm tip pipette. All proximal collections were done in the last surface segment. Fluid volume was determined from column length in a constant-bore capillary. Radioactivity in tubular fluid as well as in duplicate samples of plasma and urine was determined in a gamma counter.

GFR by FITC Inulin

GFR in conscious mice was measured according to the protocol described previously.33 Briefly, FITC inulin (3.7 ml/g BW) was injected into the retro-orbital plexus during brief isoflurane anesthesia from which the animals recovered within about 20 seconds. At 3, 7, 10, 15, 35, 55, and 75 minutes after the injection mice were placed in a restrainer, and 2 ml of blood was drawn from the tail vein. Samples were centrifuged and 500 nl of plasma was transferred into a microcapillary and diluted 1:10 in 500 mmol of HEPES (pH 7.4). Fluorescence was determined in 1.7 ml of each sample in a Nanodrop-ND-3300 fluorescence spectrometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE). GFR was calculated using a two-compartment model of two-phase exponential decay.34

Acute Kidney Injury Biomarkers

Urine samples were freshly collected and put on ice and then centrifuged within 30 minutes to remove insoluble elements. Urinary aliquots were stored at −80°C and sent to Dr. Joseph Bonventre Laboratory for blinded analysis. Real-time PCR primers for NGAL: sense 5′-CTC AGA ACT TGA TCC CTG CC-3′, antisense 5′-TCC TTG AGG CCC AGA GAC TT-3′.

Histologic Analysis

Freshly dissected kidneys were fixed in 10% formalin/PBS, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and periodic acid–Schiff. Sections were examined and photographed with a DC200 Leica camera and Leica DMLB microscope (Leica Microsystems Inc.).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test for parametric data and two-tailed χ2 for categorical data, with multiple comparisons, was performed using Graph Pad Prism version 4.00 for Windows, Graph Pad Software (San Diego). For subgroup analyses between two groups, a two-tailed t test assuming homoscedasticity was used. The null hypothesis was rejected when P < 0.05.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jasmine Bahrami and the Drucker Lab for assistance and advice regarding metabolic tests and Dr. Kamel Kamel for critical appraisal and discussion. We gratefully acknowledge the measurement of plasma renin by Yuning Huang and Diane Mizel. This work was funded by CIHR grants MOP 77756, 62931, TF grant 016002, and KFOC grant to S.E.Q., MRC grant GSP 36653 to C.M.H.D. S.E.Q. holds the Gabor-Zellerman Chair in Renal Research, UHN, University of Toronto, and is the recipient of a CRC Canada Research Chair Tier II. J.L. is supported by the KRESCENT program, Kidney Foundation of Canada, and CIHR. S.L.A. holds the Anne and Max Tanenbaum Chair, MSH.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

See related editorial, “Risks and Benefits of Sweet Pee,” on pages 2–5.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hediger MA, Rhoads DB: Molecular physiology of sodium-glucose cotransporters. Physiol Rev 74: 993–1026, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhou L, Cryan EV, D'Andrea MR, Belkowski S, Conway BR, Demarest KT: Human cardiomyocytes express high level of Na+/glucose cotransporter 1 (SGLT1). J Cell Biochem 90: 339–346, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rahmoune H, Thompson PW, Ward JM, Smith CD, Hong G, Brown J: Glucose transporters in human renal proximal tubular cells isolated from the urine of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes 54: 3427–3434, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee YJ, Han HJ: Regulatory mechanisms of Na(+)/glucose cotransporters in renal proximal tubule cells. Kidney Int Suppl (106): S27–S35, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gerich JE: Role of the kidney in normal glucose homeostasis and in the hyperglycaemia of diabetes mellitus: Therapeutic implications. Diabet Med 27: 136–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Magen D, Sprecher E, Zelikovic I, Skorecki K: A novel missense mutation in SLC5A2 encoding SGLT2 underlies autosomal-recessive renal glucosuria and aminoaciduria. Kidney Int 67: 34–41, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bakris GL, Fonseca VA, Sharma K, Wright EM: Renal sodium-glucose transport: Role in diabetes mellitus and potential clinical implications. Kidney Int 75: 1272–1277, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patel AK, Fonseca V: Turning glucosuria into a therapy: Efficacy and safety with SGLT2 inhibitors. Curr Diab Rep 10: 101–107, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bailey CJ, Gross JL, Pieters A, Bastien A, List JF: Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes who have inadequate glycaemic control with metformin: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 375(9733): 2223–2233, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Justice MJ, Noveroske JK, Weber JS, Zheng B, Bradley A: Mouse ENU mutagenesis. Hum Mol Genet 8: 1955–1963, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soewarto D, Klaften M, Rubio-Aliaga I: Features and strategies of ENU mouse mutagenesis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 10: 198–213, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santer R, Kinner M, Lassen CL, Schneppenheim R, Eggert P, Bald M, Brodehl J, Daschner M, Ehrich JH, Kemper M, Li Volti S, Neuhaus T, Skovby F, Swift PG, Schaub J, Klaerke D: Molecular analysis of the SGLT2 gene in patients with renal glucosuria. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 2873–2882, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fox JG: The Mouse in Biomedical Research, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andrikopoulos S, Blair AR, Deluca N, Fam BC, Proietto J: Evaluating the glucose tolerance test in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 295: E1323–E1332, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaku K, Fiedorek FT, Jr., Province M, Permutt MA: Genetic analysis of glucose tolerance in inbred mouse strains. Evidence for polygenic control. Diabetes 37: 707–713, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ehrenkranz JR, Lewis NG, Kahn CR, Roth J: Phlorizin: A review. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 21: 31–38, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Harbach PR, Mattano SS, Zimmer DM, Filipunas AL, Wang Y, Aaron CS: DNA sequence analysis of hprt mutants persisting in peripheral blood of cynomolgus monkeys more than two years after ENU treatment. Environ Mol Mutagen 33: 42–48, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang H, Feng J, Qi C, Morse HC, 3rd: An ENU-induced mutation in the lymphotoxin alpha gene impairs organogenesis of lymphoid tissues in C57BL/6 mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370: 461–467, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cao J, Yin M, Chen J, Xu S: [Studies on gene mutation and micronucleus formation induced by ethylnitrosourea (ENU) in transgenic mice in vivo]. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 34: 28–30, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Buhler M, Paillusson A, Muhlemann O: Efficient downregulation of immunoglobulin mu mRNA with premature translation-termination codons requires the 5′-half of the VDJ exon. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 3304–3315, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeMambro VE, Kawai M, Clemens TL, Fulzele K, Maynard JA, Marin de Evsikova C, Johnson KR, Canalis E, Beamer WG, Rosen CJ, Donahue LR: A novel spontaneous mutation of Irs1 in mice results in hyperinsulinemia, reduced growth, low bone mass and impaired adipogenesis. J Endocrinol 204: 241–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Makarov R, Steiner B, Gucev Z, Tasic V, Wieacker P, Wieland I: The impact of CFNS-causing EFNB1 mutations on ephrin-B1 function. BMC Med Genet 11: 98, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Silva AL, Pereira FJ, Morgado A, Kong J, Martins R, Faustino P, Liebhaber SA, Romao L: The canonical UPF1-dependent nonsense-mediated mRNA decay is inhibited in transcripts carrying a short open reading frame independent of sequence context. RNA 12: 2160–2170, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. You KT, Li LS, Kim NG, Kang HJ, Koh KH, Chwae YJ, Kim KM, Kim YK, Park SM, Jang SK, Kim H: Selective translational repression of truncated proteins from frameshift mutation-derived mRNAs in tumors. PLoS Biol 5: e109, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kamel KS, Oh MS, Halperin ML: Bartter's, Gitelman's, and Gordon's syndromes. From physiology to molecular biology and back, yet still some unanswered questions. Nephron 92 [Suppl 1]: 18–27, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ellison DH: Divalent cation transport by the distal nephron: Insights from Bartter's and Gitelman's syndromes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 279: F616–F625, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Carlotti AP, Bohn D, Matsuno AK, Pasti DM, Gowrishankar M, Halperin ML: Indicators of lean body mass catabolism: Emphasis on the creatinine excretion rate. QJM 101: 197–205, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilding JP, Norwood P, T'Joen C, Bastien A, List JF, Fiedorek FT: A study of dapagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving high doses of insulin plus insulin sensitizers: Applicability of a novel insulin-independent treatment. Diabetes Care 32: 1656–1662, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jun JE, Wilson LE, Vinuesa CG, Lesage S, Blery M, Miosge LA, Cook MC, Kucharska EM, Hara H, Penninger JM, Domashenz H, Hong NA, Glynne RJ, Nelms KA, Goodnow CC: Identifying the MAGUK protein Carma-1 as a central regulator of humoral immune responses and atopy by genome-wide mouse mutagenesis. Immunity 18: 751–762, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giese H, Snyder W, Van Oostrom C, Van Steeg H, Dolie M, Vijg J: Age-related mutation accumulation at a lacZ reporter locus in normal and tumor tissues of Trp53-deficient mice. Mutat Res 514:153–163, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ: Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat Protoc 3: 1101–1108, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hashimoto S, Adams JW, Bernstein KE, Schnermann J: Micropuncture determination of nephron function in mice without tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 288: F445–F452, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen L, Kim SM, Oppermann M, Faulhaber-Walter R, Huang Y, Mizel D, Chen M, Lopez ML, Weinstein LS, Gomez RA, Briggs JP, Schnermann J: Regulation of renin in mice with Cre recombinase-mediated deletion of G protein Gsalpha in juxtaglomerular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F27–F37, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Qi Z, Whitt I, Mehta A, Jin J, Zhao M, Harris RC, Fogo AB, Breyer MD: Serial determination of glomerular filtration rate in conscious mice using FITC-inulin clearance. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F590–F596, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]