Abstract

The aim of this review was to describe a patient with serotonin toxicity after an overdose of dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine and to perform a systematic literature review exploring whether dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine may be equally contributory in the development of serotonin toxicity in overdose. A Medline literature review was undertaken to identify cases of serotonin toxicity due to dextromethorphan and/or chlorphenamine. Case reports were included if they included information on the ingested dose or plasma concentrations of dextromethorphan and/or chlorphenamine, information about co-ingestions and detailed clinical information to evaluate for serotonin toxicity. Cases were reviewed by two toxicologists and serotonin toxicity, defined by the Hunter criteria, was diagnosed when appropriate. The literature was then reviewed to evaluate whether chlorphenamine may be a serotonergic agent. One hundred and fifty-five articles of dextromethorphan or chlorphenamine poisoning were identified. There were 23 case reports of dextromethorphan, of which 18 were excluded for lack of serotonin toxicity. No cases were identified in which serotonin toxicity could be solely attributed to chlorphenamine. This left six cases of dextrometorphane and/or chlorphenamine overdose, including our own, in which serotonin toxicity could be diagnosed based on the presented clinical information. In three of the six eligible cases dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine were the only overdosed drugs. There is substantial evidence from the literature that chlorphenamine is a similarly potent serotonin re-uptake inhibitor when compared with dextrometorphan. Chlorphenamine is a serotonergic medication and combinations of chlorphenamine and dextromethorphan may be dangerous in overdose due to an increased risk of serotonin toxicity.

Keywords: 5-HT, chlorphenamine, dextromethorphan, poisoning, serotonin toxicity

Introduction

Several cases of serotonin toxicity following overdose of over the counter (OTC) cough medications, containing dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine, have been described in the literature. Invariably, authors attributed the serotonin toxicity to the use of dextromethorphan or did not report co-ingestants [1–3]. However, there is evidence that co-ingested chlorphenamine may contribute significantly to serotonin toxicity in these overdoses. In this report, we aim to describe significant serotonin toxicity in a patient after ingestion of a cough medication containing dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine in a suicidal attempt. Second, we present a review of case reports involving overdose cases on dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine, and assess serotonin toxicity using the Hunter criteria [4, 5]. Third, we will present and discuss available evidence of chlorphenamine's serotoninergic properties [6, 7]. Our objective is to discuss whether there is evidence that chlorphenamine may be contributory in the development of serotonin toxicity in overdose of this combination.

Case report

A 19-year-old man was dropped off at the emergency department by his girlfriend 12 h after ingestion of up to 48 tablets of Coricidin® Cough and Cold (each tablet containing 30 mg dextromethorphan hydrobromide and 4 mg chlorphenamine maleate). The patient had been hospitalized multiple times in the past for suicidal behaviour and the patient's medical history revealed a borderline personality and anxiety disorder including panic attacks. At presentation, the patient was agitated and delirious. Limited history was obtainable due to the patient's altered mental status. His vital signs were: blood pressure 177/113 mmHg, heart rate 128 beats min–1, respiratory rate 18 min–1, temperature 38.5°C. The ocular examination was notable for mydriasis (symmetrically reactive to light) and ocular clonus. The skin felt warm and dry and mucous membranes were dry. There was axillary sweat, bowel sounds were present, and there was no urinary retention. Patellar and achilles deep tendon reflexes were increased compared with deep tendon reflexes on the upper extremities. Bilateral inducible sustained ankle clonus, lasting approximately 1 min, was noted. The clinical examination was otherwise normal. The ECG showed sinus tachycardia with normal axis, the PR, QRS and QT/QTc intervals were within normal limits. His routine laboratory values were unremarkable. The urine toxic screen was negative for THC, ethanol, PCP, cocaine, amphetamines, opiates, barbiturates and benzodiazepines. As his mental status cleared, he denied ingestion of pharmaceutical medications, illicit drugs, or any other OTC formulation except Coricidin® Cough and Cold prior to his presentation. The patient was admitted, sedated with repetitive doses of intravenous lorazepam and treated with intravenous fluids. His vital signs normalized and his mental status cleared over the next 6 h. He left the hospital with a normal neurologic examination 36 h after admission. Serum concentrations of dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Case characteristics of patients with serotonin toxicity after dextromethorphan and/or chlorphenamine overdose

| Case | Age (years)/ Gender | Co-medication | Overdosed drugs | Plasma concentrations | Probable serotonergic effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 19/M | None | Dex up to 1440 mg, cpa up to 192 mg | 12 h post-ingestion dex 250 ng ml−1cpa 330 ng ml−138 h post-ingestion dex 38 ng ml−1cpa 140 ng ml−1 | Inducible ankle clonus, ocular clonus, hyperreflexia, hypertension, tachycardia, hyperthermia |

| Schwartz [3] | 20/M | Escitalopram, benztropine | Dex, cpa amount unknown | Dex 950 ng ml−1*, cpa 430 ng ml−1† esc 23 ng ml−1‡ | Altered mental status, hyperthermia, bilateral ankle clonus, hyperreflexia and rigidity in lower extremities, hypertension, tachycardia, diaphoresis |

| Schwartz [3] | 6/M | Sertraline, caffeine | Dex, amount unknown | dDex 2820 ng ml−1ser 12.5 ng ml−1§ | Altered mental status, hyperthermia, hypertension, muscle rigidity, clonus in lower extremities |

| Ganetsky [1] | 18/M | None | Dex up to 960 mg, cpa up to 128 mg | Dex 930 ng ml−1 | Ocular clonus, hyperreflexia and rigidity in lower extremities, tremor, agitation, diaphoresis |

| Navarro [2] | 22/M | Lithium, fluoxetine, clonazepam | Several dex containing bottles of ‘cough syrup’ | Li 0.3 mmol l−1 | Clonus, nystagmus, hyperreflexia, agitation, hyperthermia, diaphoresis hypertension, tachycardia |

| Skop [8] | 51/M | Diltiazem, nitroglycerin, ticlopidin, piroxicam, ranitidine, paroxetine | Nyquil®[dex, doxylamine, pseudoephedrine, paracetamol (acetaminophen)], amount not reported | Not reported | Diaphoresis, tremor, confusion, hypertension, tachycardia, clonus, muscle rigidity |

Dex concentration 2.5 h after single oral dose of 20 mg in healthy volunteers: 1.8 ng ml−1.

Cpa reference concentration reported <20 ng ml−1.

Escitalopram reference concentration reported <200 ng ml−1.

Sertraline reference concentration reported <200 ng ml−1. Dex, dextromethorphan; cpa, chlorphenamine; esc, escitalopram; ser, sertraline.

Literature review methods

A MEDLINE search was performed using Pubmed to identify all English language case reports of dextromethorphan or chlorphenamine induced serotonin toxicity published through December 2009. The search terms ‘dextromethorphan poisoning’ and ‘chlorphenamine poisoning’ were employed. The search results were reviewed to identify cases reports of toxicity from these agents. References of the reviewed cases were reviewed to ensure capture of all relevant cases. Cases were independently reviewed by two toxicologists (MB and AM) to determine their eligibility for inclusion. Discrepancies were arbitrated by a third toxicologist (RC). Cases that involved both dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine were reviewed once and grouped with the dextromethorphan cases, since toxicity was uniformly attributed to that agent. Case reports needed to fulfill three criteria to be included. First, information of ingested dextromethorphan or chlorphenamine product and/or dose or plasma concentrations had to be reported. Second, information about co-ingestions had to be available. Third, detailed clinical information had to be provided to evaluate for serotonin toxicity defined by the Hunter criteria. Reports were excluded if insufficient clinical data were available to assess the Hunter criteria for evaluation of serotonin toxicity.

Results of literature review

Our literature review identified 76 articles of dextromethorphan poisoning and 79 results for chlorphenamine poisoning. Fifty-three of the dextromethorphan articles and 71 of the chlorphenamine articles were excluded because they were either reviews that did not report cases of dextromethorphan or chlorphenamine toxicity or because they were studies of other agents without description of dextromethorphan or chlorphenamine adverse effects. There were 23 case reports of dextromethorphan, of which 18 were excluded for lack of serotonin toxicity or insufficient clinical information to evaluate for serotonin toxicity. Six cases involving chlorphenamine, with co-ingestants but without dextromethorphan, were reviewed. However there were no cases in which serotonin toxicity was observed. This left six cases, including our own, of serotonin toxicity in association with dextrometorphan of which three also overdosed on chlorphenamine [1, 3] that full-filled our inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarizes included cases with the diagnosis of serotonin toxicity after dextromethorphan overdose. In the case described by Skop and colleagues [8], paroxetine, in addition to its contribution as a SSRI, is also a strong cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 inhibitor, likely leading to increased half-life of dextromethorphan due to impairment of its liver metabolism mediated by CYP 2D6. In the cases by Schwartz et al. escitalopram and sertraline likely contributed to the development of serotonin toxicity [3]. However, in three of the six eligible cases, including our own [1, 3], dextromethorphan and chlorphenamine were the only overdosed drugs. Neither dextromethorphan nor chlorphenamine alone have been found to be associated with significant serotonin toxicity in overdose. Therefore, it can be speculated that chlorphenamine itself may exhibit serotonergic properties.

Discussion

In our patient, bilateral ankle clonus, hyperreflexia at the lower extremities, tachycardia, hypertension and hyperthermia were consistent with moderate serotonin toxicity whereas dry skin and mucous membranes, as well as tachycardia may also be explained by the anticholinergic effects of chlorphenamine. However, the presence of bowel sounds and the presence of axillary sweat argue against a pure anticholinergic toxidrome. While a mixed toxidrome is likely given the known clinical effects of the ingested agents, inducible clonus is strongly suggestive of increased serotonergic tone in this patient. Although unlikely in our case, it has to be noted that we were not able to definitely exclude other ingested serotonergic drugs since we did not send for a comprehensive toxicologic screening.

Serotonin toxicity is caused by excessive central and peripheral stimulation of serotonin (5-HT) receptors. No single receptor seems to be responsible for the development of serotonin toxicity in any individual patient but it has been shown that 5-HT2A may play a major role and other subtypes, such as 5-HT1A, may contribute [4, 9]. It is important to recognize that serotonin toxicity is primarily a clinical diagnosis that encompasses many clinical findings in several organ systems. Therefore, a high grade of clinical suspicion and application of the Hunter diagnostic criteria are advisable to help establish the diagnosis [5]. Most common symptoms and signs of serotonin toxicity include neuromuscular findings (hyperreflexia, rigidity, spontaneous or inducible clonus), autonomic signs (hypertension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, diarrhoea), and mental status abnormalities (agitation, delirium). Hyperthermia is seen in association with muscular rigidity in moderate to severe serotonin toxicity. Serotonin toxicity most commonly develops within hours after ingestion of two or more serotonergic agents, such as serotonin re-uptake inhibitors, inhibitors of monoamine oxidase (MAOIs) and drugs enhancing serotonin release [4].

Described in depth by Boyer [4] and Ganetsky [1], dextromethorphan is a moderate serotonin re-uptake inhibitor [4, 9], compared with more potent serotonin re-uptake inhibitors such as paroxetine and escitalopram. Dextromethorphan also promotes serotonin release [10]. In addition, NMDA receptor antagonism by dextromethorphan and its metabolite dextrorphan is associated with postsynaptic 5-HT2A stimulation [11]. Therefore, NMDA receptors may play an important role in the glutamate modulation of serotonergic function at the postsynaptic 5-HT2A receptors.

Overdose with dextromethorphan leads to NMDA receptor antagonism in a dose-dependent manner. Hallucinogenic effects may be observed after ingesting 200–600 mg of dextromethorphan [10]. Dissociative effects may be seen at larger doses and are associated with autonomic effects (tachycardia, hypertension, diaphoresis), nystagmus and ataxia [10]. Whereas autonomic disturbances may be explained by serotonin toxicity, hyperadrenergic state, anticholinergic effects, or NDMA antagonism, the signs of hyperreflexia, clonus, and rigidity may help to differentiate serotonin toxicity from other toxidromes. However, it must be acknowledged that NDMA receptor antagonism may increase serotonin neurotransmission [11].

The serotonergic properties of dextromethorphan are well recognized and accordingly, this drug is listed as a contributor to serotonin toxicity [4, 9]. However, to our knowledge, serotonin toxicity, as defined in our study, has never been described in patients overdosing with dextromethorphan as a single agent, though some reports have documented serotonin toxicity with only chlorphenamine as a co-ingestant (Table 1).

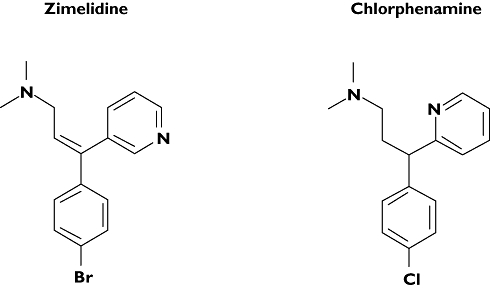

Chlorphenamine was introduced in 1950 in the United States as a first generation H1-histamine receptor antagonist with potent antimuscarinic properties. Forty years ago, Carlsson reported on the ability of chlorphenamine to block serotonin uptake [12]. From the experiments with various antihistamines these authors concluded that chlorphenamine may be a promising serotonin re-uptake inhibitor and after marginal structural modification (Figure 1), zimelidine was patented 1972 as the first selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor [13]. However, this drug was later withdrawn from the market because of rare but serious side effects. Tatsumi demonstrated in vitro that chlorphenamine had a similar affinity for the human 5-HT transporter as venlafaxine, desipramine or nortriptyline and a 10-fold higher affinity than zimelidine [14]. In addition to Tatsumi [14] and Carlsson [12], several studies provided evidence that chlorphenamine exhibits considerable affinity to the 5-HT transporter and could significantly inhibit serotonin re-uptake (Ki 31 nmol l−1, IC50 89 nmol l−1[15]) [16–19]. For dextromethorphan, by comparison, a similar affinity to the 5-HT transporter was reported (Ki 23 nmol l−1), comparable with the values of nortriptyline (Ki = 19 nmol l−1) and norfluoxetine (Ki = 25 nmol l−1) [16]. Recently, it was shown that chlorphenamine produced anxiolytic like effects in mice, at least in part, due to augmentation of serotonergic neurotransmission and independent of H1-receptor antagonism [20]. In addition, chlorphenamine was shown to enhance 5-HT1A mediated locomotor stimulation in rats [21]. These observations provide substantial evidence that chlorphenamine may be a serotonergic drug and contributes to the clinical toxicity in our case and the other reviewed cases (Table 1). Of note, single ingestion of chlorphenamine as a sole agent, has never been associated with serotonin toxicity. However, it should be noted that serotonin toxicity most often develops in patients using two or more serotoninergic drugs simultaneously. In addition, there is no evidence that dextrometorphan alone is associated with serotonin toxicity. This effect has only been reported in combination with an SSRI or chlorphenamine.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of zimelidine, the first patented SSRI, and chlorphenamine

Given that dextromethorphan was first introduced in 1958 and chlorphenamine in 1950, there may be reports of serotonin toxicity in the literature that pre-date the Pubmed database. Serotonin toxicity was first recognized and described by Oates in 1960 [22]. However, Mackey found that 85% of physicians were unaware of the diagnosis as recently as 1999 [23]. Therefore, many cases of serotonin toxicity may have been overlooked in the ensuing years of drug availability. To minimize the risk of missing cases with potential serotonin toxicity, we included any cases of possible serotonin toxicity by reviewing the presented clinical data in the original reports using the Dunkley criteria even if serotonin toxicity was not diagnosed by the authors.

In conclusion, we believe that chlorphenamine should be considered a serotonergic drug. Therefore, cough medications containing chlorphenamine and dextromethorphan may be dangerous in overdose, due their cumulative serotonergic effects increasing the potential to cause significant serotonin toxicity. The use of these combination products should be discouraged given their marginal efficacy in therapeutic use [24], the propensity for abuse [10] and the potential for serious toxicity in overdose.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ganetsky M, Babu KM, Boyer EW. Serotonin syndrome in dextromethorphan ingestion responsive to propofol therapy. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:829–31. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31815a0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro A, Perry C, Bobo WV. A case of serotonin syndrome precipitated by abuse of the anticough remedy dextromethorphan in a bipolar patient treated with fluoxetine and lithium. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:78–80. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz AR, Pizon AF, Brooks DE. Dextromethorphan-induced serotonin syndrome. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2008;46:771–3. doi: 10.1080/15563650701668625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1112–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96:635–42. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alisky JM. Can chlorpheniramine cause serotonin syndrome? Singapore Med J. 2006;47:1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karamanakos PN. Can chlorpheniramine cause serotonin syndrome? Singapore Med J. 2007;48:482. author reply 483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skop BP, Finkelstein JA, Mareth TR, Magoon MR, Brown TM. The serotonin syndrome associated with paroxetine, an over-the-counter cold remedy, and vascular disease. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12:642–4. doi: 10.1016/0735-6757(94)90031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:434–41. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyer EW. Dextromethorphan abuse. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:858–63. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000148039.14588.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HS, Park IS, Lim HK, Choi HS. NMDA receptor antagonists enhance 5-HT2 receptor-mediated behavior, head-twitch response, in PCPA-treated mice. Arch Pharm Res. 1999;22:113–8. doi: 10.1007/BF02976533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlsson A, Lindqvist M. Central and peripheral monoaminergic membrane-pump blockade by some addictive analgesics and antihistamines. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1969;21:460–4. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1969.tb08287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlsson A, Wong DT. Correction: a note on the discovery of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Life Sci. 1997;61:1203. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00662-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tatsumi M, Groshan K, Blakely RD, Richelson E. Pharmacological profile of antidepressants and related compounds at human monoamine transporters. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;340:249–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh S, Dersch C, Rothman R, Cadet J. Effects of antihistamines on 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-induced depletion of serotonin in rats. Synapse. 1999;33:207–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(19990901)33:3<207::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Codd EE, Shank RP, Schupsky JJ, Raffa RB. Serotonin and norepinephrine uptake inhibiting activity of centrally acting analgesics: structural determinants and role in antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1263–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lidbrink P, Jonsson G, Fuxe K. The effect of imipramine-like drugs and antihistamine drugs on uptake mechanisms in the central noradrenaline and 5-hydroxytryptamine neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1971;10:521–36. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(71)90018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shishido S, Oishi R, Saeki K. In vivo effects of some histamine H1-receptor antagonists on monoamine metabolism in the mouse brain. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1991;343:185–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00168608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young CS, Mason R, Hill SJ. Inhibition by H1-antihistamines of the uptake of noradrenaline and 5-HT into rat brain synaptosomes. Biochem Pharmacol. 1988;37:976–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(88)90194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyata S, Hirano S, Ohsawa M, Kamei J. Chlorpheniramine exerts anxiolytic-like effects and activates prefrontal 5-HT systems in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1695-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karamanakos PN, Pappas P, Marselos M. Involvement of the brain serotonergic system in the locomotor stimulant effects of chlorpheniramine in Wistar rats: implication of postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptors. Behav Brain Res. 2004;148:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(03)00193-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oates JA, Sjoerdsma A. Neurologic effects of tryptophan in patients receiving a monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Neurology. 1960;10:1076–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.10.12.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackay FJ, Dunn NR, Mann RD. Antidepressants and the serotonin syndrome in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:871–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter medications for acute cough in children and adults in ambulatory settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001831.pub3. CD001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]