Abstract

Rfv3 is an autosomal dominant gene that influences the recovery of resistant mice from Friend retrovirus (FV) infection by limiting viremia and promoting a more potent neutralizing antibody response. We previously reported that Rfv3 is encoded by Apobec3, an innate retrovirus restriction factor. However, it was recently suggested that the Rfv3 susceptible phenotype of high viremia at 28 days postinfection (dpi) was more dominantly controlled by the B-cell-activating factor receptor (BAFF-R), a gene that is linked to but located outside the genetically mapped region containing Rfv3. Although one prototypical Rfv3 susceptible mouse strain, A/WySn, indeed contains a dysfunctional BAFF-R, two other Rfv3 susceptible strains, BALB/c and A.BY, express functional BAFF-R genes, determined on the basis of genotyping and B-cell immunophenotyping. Furthermore, transcomplementation studies in (C57BL/6 [B6] × BALB/c)F1 and (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice revealed that the B6 Apobec3 gene significantly influences recovery from FV viremia, cellular infection, and disease at 28 dpi. Finally, the Rfv3 phenotypes of prototypic B6, A.BY, A/WySn, and BALB/c mouse strains correlate with reported Apobec3 mRNA expression levels. Overall, these findings argue against the generality of BAFF-R polymorphisms as a dominant mechanism to explain the Rfv3 recovery phenotype and further strengthen the evidence that Apobec3 encodes Rfv3.

Following the discovery of Friend virus (FV) in 1957 (15), studies of different mouse strains infected with FV provided numerous insights into host genetic control of retroviral infections (9, 18, 32). FV infection of susceptible mice, such as BALB and A strains, results in the rapid proliferation of erythroblast precursors, leading to erythroleukemia and death. On the other hand, two related mouse strains, C57BL/6 (B6) and C57BL/10 (B10) (3), contain both immunological and nonimmunological resistance genes and do not develop leukemia. One resistance gene is Recovery from Friend Virus gene 3, or Rfv3. Rfv3 was discovered by Chesebro and Wehrly while studying the phenotypes of crosses and backcrosses between a resistant strain (B10) and susceptible strains (A.BY, A/WySn, and BALB.B) (10) (Table 1). Rfv3 was determined to be a single autosomal gene that acted in a dominant manner to promote the recovery of mice from splenomegaly and leukemia by stimulating the development of neutralizing antibody (NAb) responses and inhibiting viremia (10, 12, 14).

TABLE 1.

FV infection phenotypes and genotypes of mouse strains relevant to Rfv3

| Type | Strain | Fv2 genotypea | Splenomegaly | Rfv3 genotype | Viremia | NAbe | H-2 genotypea | Cellular immunity | Recovery | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inbred | B6b | r/r | Low | r/r | Low | High | b/b | High | High | 27, 40, 42, 48 |

| B10b,c | r/r | Low | r/r | Low | High | b/b | High | High | 9, 13 | |

| B10.Ac | r/r | Low | r/r | Low | High | a/a | Low | High | 9, 13 | |

| A/WySn | s/s | Intermediate | s/s | High | Low | a/a | Low | Low | 10, 48 | |

| A.BY | s/s | Intermediate | s/s | High | Low | b/b | High | Low | 10, 42d | |

| BALB.Bc | s/s | Severe | s/s | High | Low | b/b | High | Low | 10, 13 | |

| BALB/cc | s/s | Very severe | s/s | High | Low | d/d | Low | Low | 13, 27, 42 | |

| F1 hybrids | B10.A × A/WySn | r/s | Severe | r/s | Acutef | High | a/a | Low | Low | 10, 19, 22, 45 |

| B6 × A/WySn | r/s | Severe | r/s | Acute | High | a/b | Medium | Medium | 48 | |

| B10 × A.BY | r/s | Severe | r/s | Acute | High | b/b | High | High | 10, 13 | |

| B6 × A.BY | r/s | Severe | r/s | Acute | High | b/b | High | High | 40, 42d | |

| B10 × BALB.B | r/s | Severe | r/s | Acute | High | b/b | High | High | 10, 13 | |

| B6 × BALB/c | r/s | Severe | r/s | Acute | High | b/d | Medium | Medium | 42d |

Fv2 facilitates splenomegaly induction, while H-2 is the major histocompatibility complex and controls cellular immunity (9, 18, 32).

B6 and B10 strains were separated from a nearly inbred C57BL line in 1921 (3).

B10 and B10.A and BALB.B and BALB/c are congenic strains, respectively, that differ only in the H-2 locus.

Data to support these designations are also presented in this study.

NAb response.

The level of viremia is high during acute infection but resolves.

Three mapping studies have been performed to determine the molecular identity of Rfv3 (19, 22, 45) (Table 1). Plasma viremia at 1 month postinfection was used to determine the Rfv3 phenotypes of intercrosses and backcrosses between B10.A (Rfv3r/r) and A/WySn (Rfv3s/s) mice, and microsatellite markers were used to map associated chromosomal regions. The first two studies mapped Rfv3 to a 0.83-centimorgan region on chromosome 15 that contained approximately 130 genes (19, 45). A third study by the Miyazawa group (22) further narrowed this region to a 61-gene segment and confirmed an association between Rfv3 action and the development of NAbs.

The sequencing of the mouse genome (49) facilitated direct analysis of the gene composition of the Rfv3 chromosomal region. Comparison of the Rfv3 regions of B6 (Rfv3r/r) and A (Rfv3s/s) mice revealed the enrichment of polymorphisms and signals of positive selection in the Apobec3 gene in contrast to the 60 other genes (42). Because Apobec3 exhibits broad antiretroviral activity (as reviewed in reference 41), B6 Apobec3-deficient mice were developed to investigate whether Rfv3 was encoded by Apobec3. The Apobec3-deficient mice displayed an Rfv3 susceptible phenotype, but it was theoretically possible that Apobec3 deficiency might simply mimic the Rfv3 susceptible phenotype. To exclude this possibility, transcomplementation experiments mice were performed in F1 mice. Both Apobec3 and Rfv3 act in a dominant manner to confer resistance. If they were distinct genes, then F1 offspring from B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY (Rfv3s/s) crosses would have an Rfv3r/s/Apobec3−/+ genotype and a resistant phenotype. In fact, these mice had an Rfv3 susceptible phenotype (42). The failure of B6 Apobec3−/− to transcomplement the susceptible Rfv3 allele of A.BY provided strong evidence of identity between Apobec3 and Rfv3. Subsequent to this report, Takeda et al. correlated Apobec3 polymorphisms with Rfv3 genotypes and suggested that Rfv3 was encoded by Apobec3 (46).

Recently, the Miyazawa group called into question whether the Rfv3 phenotype was due to Apobec3 (48). They confirmed the ability of the wild-type B6 Apobec3 gene to promote FV-specific NAb responses in the (B6 × A/WySn)F1 background. However, they suggested the involvement of a linked gene, B-cell-activating factor receptor (BAFF-R). Both BAFF-R and Apobec3 were located within the Rfv3 region in the first two mapping studies (19, 45). However, the latest Rfv3 mapping study excluded BAFF-R, since it is located ∼300,000 bp outside D15Mit118, the proposed telomeric boundary of the Rfv3 region (22). The recent contention that BAFF-R encodes Rfv3 was prompted by the finding that A/WySn mice displayed 8.4-fold higher plasma viremia at 28 days postinfection (dpi) than A/J mice (48). A/J and A/WySn mice have a common origin but exhibit critical differences in B-cell phenotypes: A/WySn mice contain lower B-cell numbers, a decreased percentage of B cells in the spleen, and defects in B-cell maturation in the bone marrow (31). A/J and A/WySn intercrosses mapped this phenotype to the codominant Bcmd locus (21), which was subsequently named BAFF-R. The defective B-cell phenotype in A/WySn mice was later attributed to the replacement of 8 amino acids in the C terminus of BAFF-R with 21 amino acids encoded by an intracisternal A-particle (IAP) element (2, 47, 50). Current evidence suggests that this modification results in aberrant BAFF-R signaling, leading to decreased B-cell maturation and survival (28).

The Miyazawa group reported that B6 BAFF-R−/− mice exhibited >18.5-fold higher viremia at 28 dpi than B6 Apobec3−/− mice (48). On the basis of these data, the authors concluded that the BAFF-R defect better accounted for the Rfv3 recovery phenotype than Apobec3. However, the Rfv3 recovery phenotype was not originally defined in highly resistant pure B6 or B10 strains (27) but was defined in F1 strains that are susceptible to splenomegaly (Table 1) (9, 13). In fact, the authors demonstrated that (B6 Apobec3−/− × A/WySn)F1 mice have higher viremia at 28 dpi and weaker NAb responses than (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A/WySn)F1 mice (48), a result that is completely consistent with our prior findings in (B6 × BALB/c)F1 and (B6 × A.BY)F1 backgrounds (42). Surprisingly, the authors still concluded that BAFF-R accounts for the Rfv3 recovery phenotype, despite the fact that the key comparison with (B6 BAFFR−/− × A/WySn)F1 mice was not performed. Thus, the role of BAFF-R in exacerbating the Rfv3 recovery phenotype in (B6 × A/WySn)F1 mice remains unclear.

Aside from A/WySn mice, A.BY and BALB strains were also utilized extensively for defining Rfv3 (10). Thus, if BAFF-R polymorphisms primarily account for the Rfv3 recovery phenotype, these strains should also have the same defect observed in A/WySn mice. The Jackson Laboratory describes the A.BY strain as having been backcrossed once to the A/WySn line during its derivation (http://jaxmice.jax.org/strain/000140.html). Thus, the A.BY and A/WySn strains could have similar B-cell phenotypes due to shared BAFF-R polymorphisms.

We therefore evaluated the A.BY and BALB/c strains and show that both these strains express a functional BAFF-R. Thus, while BAFF-R deficiency may mimic the Rfv3 susceptible phenotype of high viremia because of defective B-cell responses, the BAFF-R defect does not fit the strain distribution of Rfv3. As further evidence that Rfv3 is encoded by Apobec3, we now show that, in addition to influencing neutralizing antibody responses (42), the B6 Apobec3 gene also significantly influences recovery from viremia and disease at 1 month postinfection in F1 crosses with both BALB/c and A.BY mice. Finally, in contrast to BAFF-R functional differences, Apobec3 mRNA expression levels fit the strain distribution of Rfv3. Thus, the preponderance of evidence strongly indicates that Rfv3 is encoded by Apobec3, and while BAFF-R defects may exacerbate viremia in A/WySn mice, it is not Rfv3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

B6, BALB/c, A.BY, A/WySn, A/J, and B10.A mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Strain 129/Ola was obtained from Harlan (Indianapolis, IN). B6 Apobec3-deficient mice were derived from the XN450 cell line (44) and backcrossed for 9 generations. All studies were performed in accordance with institutional policies for animal care and use at the University of Colorado Denver and the University of California San Francisco.

BAFF-R and Apobec3 genotyping.

To determine BAFF-R genotypes, we employed a PCR scheme based on a forward primer anchored to exon 3 of BAFF-R (primer 1, 5′-CCTCCTCAGAAACCCCTCAT) and a reverse primer anchored either to wild-type BAFF-R (primer 2, 5′-CGGCTAGAACAGCACACAAA) or the IAP insertion characterized in A/WySn mice (primer 3, 5′-ACGTTCACGGGAAAAACAGA) (2, 28). To facilitate multiplexing, the primers were designed to amplify different sizes depending on the genotype (Fig. 1A). To detect the presence of a 531-bp retroviral insertion in the B6 Apobec3 exon 2 splice donor site (43), we utilized a forward primer in exon 2 (5′-CCTTCACCATGGGGTCTTTA) and a reverse primer in exon 3 (5′-GATGTCCAGGCTCAGGTTGT) of Apobec3. Tail-clip DNA samples from different mouse strains were extracted, and 50 to 100 ng was added into a 40-μl PCR mixture containing 1× Sweet PCR mix (SA Biosciences, Frederick, MD) and 20 pmol of each of the three BAFF-R primers described above. For BAFF-R genotyping, the samples were subjected to a 15-min hot start at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles at 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min. The extension time was increased to 4 min for Apobec3 genotyping. PCR products were visualized in a 1.5% agarose gel.

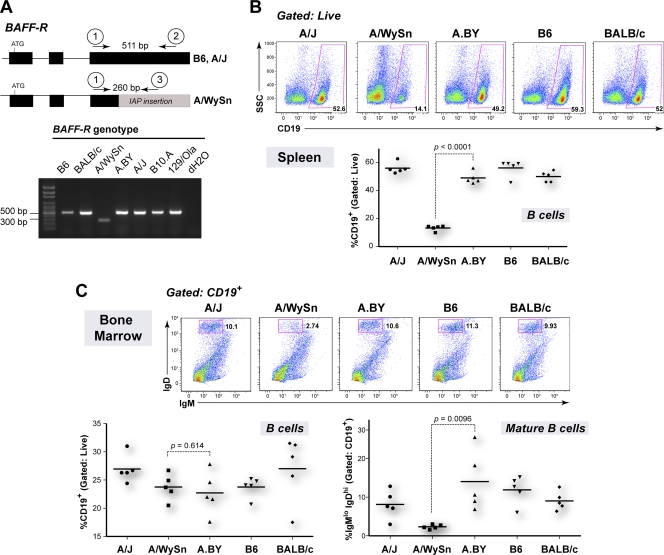

FIG. 1.

Functional BAFF-R in A.BY and BALB/c mice. (A) BAFF-R genotyping. Primers anchored to BAFF-R exon 3 that are identical (primer 1) and distinct (primers 2 and 3) between A/J and A/WySn mice were designed for multiplex PCR. Primer 3, in particular, is specific for the IAP insertion that functionally modified A/WySn BAFF-R. Tail-clip DNA samples from several mouse strains were used for genotyping. The amplification of a 511-bp band but not a 260-bp band in A.BY and BALB/c mice indicates that these strains lack the IAP modification and encode a functional BAFF-R. (B) B-cell proportions in the spleen. (Upper panel) Representative flow cytometry plots, gated from the live spleen population, show reduced B-cell percentages in A/WySn mice; (lower panel) A.BY and BALB/c strains have normal B-cell percentages, consistent with a functional BAFF-R. (C) Bone marrow B-cell immunophenotyping. (Lower left panel) B-cell percentages do not vary between the mouse strains; (upper panels) representative flow cytometry plots showing the gating strategy for quantifying mature, IgMlowIgDhigh B cells in the bone marrow; (lower right panel) in contrast to A/WySn mice, A.BY and BALB/c mice maintained normal levels of mature B cells, indicative of BAFF-R function. Data sets were analyzed by Student's t test, with exact P values being noted. Due to their common origin, the differences between A/WySn and A.BY strains were highlighted.

Apobec3 mRNA quantification.

Total Apobec3 mRNA levels were quantified as described previously (40). Briefly, total RNA was extracted from normal B6, A.BY, and BALB/c mice using an RNEasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and 10 ng was used for cDNA synthesis using random hexamers in an RT2 reverse transcription (RT) kit (SA Biosciences). Real-time PCR was performed using different primer sets (see Fig. 4). Total Apobec3 copy numbers were quantified using primers mA3.F (5′-CTGCCATGGACCTATACGAA) and mA3.R (5′-TCCTGAAGCTTAGAATCCTGGT) and a TaqMan probe, mA3.P (5′-FAM-CCAAGGCCTGAATCGCCTGC-TAMRA-3′, where FAM is 6-carboxyfluorescein). Exon 2-positive (Exon2+) transcripts utilized primers mA3x2.F (5′-CGGAAAGATACCTTCTTGTGC) and mA3x2.R (5′-CGTGGATGTTGTCCTTGTTC) and a TaqMan probe, mA3x2.P (5′FAM-TGCGATTCACCCGTCTCCCTT-TAMRA-3′, where TAMRA is 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine). Total and Exon2+ Apobec3 quantifications were performed in a 22-μl reaction mixture containing 2 μl cDNA with 20 nM primers and probe in 1× TaqMan universal master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using a 95°C 15-min hot start, followed by 40 cycles of 94°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. Beta-actin levels were quantified using mouse beta-actin primers (catalogue no. PPM02945A; SA Biosciences). Beta-actin levels were estimated using SYBR green (Applied Biosystems). Relative Apobec3 levels were interpolated from in-plate standards of known copy number, using a power equation (r2 > 0.98). The ratio of Apobec3 total or Exon2+ levels and beta-actin levels were normalized against the lowest value.

Detection of Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts.

Spleen cDNA samples from B6, BALB/c, A.BY, and A/WySn mice were subjected to an end-point PCR with primers positioned in exon 1 (5′-AGCCATCGCAAATGCTATTC) and exon 4 (5′-TCCTGAAGCTTAGAATCCTGGT) using the conditions outlined above in the “BAFF-R and Apobec3 genotyping” section. Primers biased for detecting Apobec3 transcripts lacking exon 2 (Δ2) transcripts included mA3Δ2.F (5′-ATGCTATTCACCGATCAGGACA), which is based on the exon 1/exon 3 junction, and mA3Δ2.R (5′-TGAAGATGTCCAGGCTCAGGT). Apobec3 Δ2 levels were estimated using SYBR green (Applied Biosystems), as outlined above.

FV infection.

Virus stocks were prepared and titers were determined as described previously (42). To ensure relevance for the historical Rfv3 phenotype (10), we utilized the original B-tropic FV stock that contained Friend murine leukemia helper virus, spleen focus-forming virus, and lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (38). This virus complex was used in the original studies defining Rfv3 (10) and in all three mapping studies of Rfv3 (19, 22, 45). In addition, all mouse strains infected in these studies are Fv1b/b and are therefore susceptible to B-tropic FV infection. (B6 × BALB/c)F1 mice were infected intravenously with 140 spleen focus-forming units (SFFUs) of FV stock, while (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice were infected with 1,400 SFFUs. Plasma, spleen, and bone marrow were harvested at the indicated time points.

Viremia and spleen infectious titers.

Levels of viremia were quantified by serially diluting plasma and incubating with Mus dunni cells pretreated with 4 μg/ml Polybrene, as described previously (42). Spleen infectious centers were determined by cocultivation of serially diluted splenocytes with Mus dunni cells. After 2 to 3 days, the Mus dunni cells were fixed with 100% ethanol, washed 3 times with TNE buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA), and then incubated with monoclonal antibody (MAb) 720 supernatant for 3 to 4 h at room temperature. MAb 720 binds to the Friend virus gp70 protein even after cell fixation (37). Following two washes with TNE buffer, 1:500 goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugate (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was incubated for 1 h. After two washes with TNE buffer, MAb 720-positive cells were developed with aminoethylcarbazole (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), and the number of foci was counted. Plasma viremia was expressed as the number of focus-forming units (FFUs) per ml of plasma, while spleen infectious centers were expressed as the number of FFUs per spleen.

Plasma viral load.

FV RNA copy numbers were measured using a slight modification of a recently published quantitative real-time PCR protocol (20). Viral RNA from plasma samples (10 μl) was extracted using an RNEasy kit and eluted into 100 μl of buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Ten microliters of this extract was combined with 15 μl of a master mixture containing 1× TaqMan one-step RT-PCR mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and 10 pmol of FV-specific primers (FLVsense, 5′-GGACAGAAACTACCGCCCTG; FLVantisense, 5′-ACAACCTCAGACAACGAAGTAAGA) and probe (FLVprobe, 5′-FAM-TCGCCACCCAGCAGTTTCAGCAGC-TAMRA). T7-transcribed RNA derived from the FV molecular clone pLRB302 (34) was quantified (Nanodrop Products, Wilmington, DE), serially diluted 10-fold, and included as a standard for each plate. The thermal cycling conditions in an ABI TaqMan 7300 machine included a reverse transcription step at 48°C for 15 min, a hot start for 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 s) and annealing/elongation (60°C for 1 min). RNA copy numbers were computed from the in-plate standard curves using ABI 7300 software. Using this procedure, we routinely achieve linear r2 values of >0.98 within a 7-log range, down to 10 copies per reaction mixture. With an equivalent of 1 μl input plasma per reaction mixture, the current assay has a limit of detection of 10,000 copies/ml of plasma.

Flow cytometry.

Quantification of FV-positive (FV+) cells was performed as described previously (40). Briefly, cells were stained with MAb 34 (8) hybridoma supernatant for 1 h at 4°C, followed by a rat anti-IgG2b antibody conjugated to allophycocyanin (Columbia Biosciences, Columbia, MD) to detect Glyco-Gag-positive cells. For B-cell immunophenotyping, splenocytes and bone marrow cells were stained with IgM-fluorescein isothiocyanate (clone II/41) (Biolegend, San Diego, CA), IgD-phycoerythrin (11-26c.2a), and CD19-peridinin chlorophyll protein Cy5.5 (6D5) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and the corresponding isotype controls. Cells were phenotyped in a FACSCalibur II machine (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), collecting 80,000 to 120,000 events per sample, and data were analyzed using Flowjo software (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

Statistical analyses.

Differences between means were compared using a two-tailed Student's t test. Survival was evaluated using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test using Prism (version 5.0) software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Prototypic Rfv3 susceptible strains BALB/c and A.BY express functional BAFF-R.

In order to determine the BAFF-R status of A.BY and BALB/c mice, we generated genotyping primers spanning the known IAP insertion in exon 3 of the BAFF-R gene in A/WySn mice (2) (Fig. 1A). Our results confirmed that B6 and A/J mice do not contain the IAP insertion found in the BAFF-R gene of A/WySn mice (28, 47, 50). Consistent with the findings of prior studies suggesting normal BAFF-R function in the B cells of BALB/c mice (17, 39), this strain similarly did not contain the IAP insertion in the BAFF-R gene. Likewise, the IAP insertion was not detected in A.BY mice. Thus, there was no genetic evidence for BAFF-R defects in either Rfv3s/s BALB/c or A.BY mice.

The mouse strains were next tested for BAFF-R function. The BAFF-R mutation in the A/WySn line reduces the percentage of B cells in the spleens of adult mice to 15%. In contrast, the percentage of B cells in the spleens of A/J mice is ∼50%. (A/J × A/WySn)F1 offspring exhibit an intermediate phenotype, with the mice having 30% splenic B cells, consistent with the codominance of the BAFF-R/Bcmd phenotype (31). We therefore evaluated the B-cell percentages in the spleens of five mouse strains. Consistent with prior data (31), splenic B-cell percentages were significantly higher in A/J mice than in A/WySn mice (Fig. 1B, upper panel). BALB/c and A.BY mice also exhibited splenic B-cell percentages significantly higher than those in A/WySn mice (Fig. 1B, lower panel).

Low B-cell percentages in the spleens of A/WySn mice have been linked to decreased survival of mature B cells (31). Mature B cells are characterized by cell surface expression of low IgM and high IgD (6, 17) (Fig. 1C, upper panels). No significant difference in the total B-cell percentages in bone marrow was observed between A/WySn and A.BY mice (Fig. 1C, lower left panel). In contrast, the mean percentage of mature IgMlowIgDhigh B cells in A/WySn mice was significantly reduced relative to the mean percentages for the A/J, B6, A.BY, and BALB/c strains (Fig. 1C, lower right panel). Altogether, these genetic and biological data provide strong evidence that Rfv3s/s BALB/c and A.BY mice express functional BAFF-R. Thus, while defective BAFF-R may accentuate the Rfv3 susceptible phenotype of A/WySn mice, these findings are inconsistent with the notion that the BAFF-R locus encodes Rfv3.

B6 Apobec3 is critical for recovery from FV viremia and disease in (B6 × BALB/c)F1 mice.

In their study suggesting that Rfv3 was encoded by the BAFF-R locus, the Miyazawa group stated that B6 Apobec3 deficiency did not fully recapitulate the Rfv3 susceptible phenotype of high viremia at 28 dpi (48). We previously reported a 14.3-fold increase in plasma viremia at 28 dpi in surviving (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice compared to that in (B6 Apobec3+/+ × BALB/c)F1 mice. However, because of the increased mortality of these (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice, statistical significance was not achieved (42). We therefore performed additional FV infections in a larger number of mice and analyzed the combined data set. As shown in Fig. 2A, B6 Apobec3 deficiency resulted in significantly increased mortality during the study period, with (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice exhibiting a median survival time of only 15 days. At 28 dpi, the infectious plasma viremia titers in the surviving (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice were at least 8.8-fold higher than the average titers found in (B6 Apobec3+/+ × BALB/c)F1 mice. This difference was highly significant (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2B).

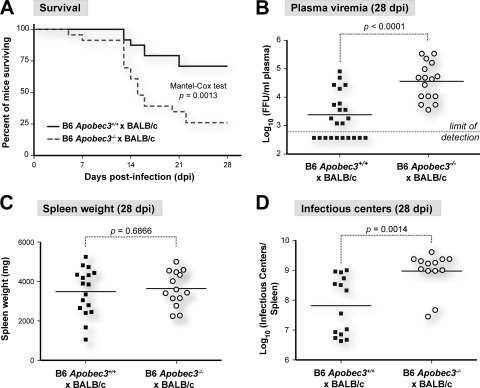

FIG. 2.

Apobec3 influences the recovery of BAFF-R-sufficient (B6 × BALB/c)F1 mice from FV. (A) B6 Apobec3 promotes survival from FV disease. FV-infected mice (140 SFFUs) from three independent cohorts (wild-type F1 mice, n = 24; Apobec3 knockout F1 mice, n = 23) were monitored daily following infection. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed and analyzed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (B) Impaired viremia recovery in B6 Apobec3-deficient mice. Plasma samples were obtained from four independent cohorts of surviving mice at 28 dpi, and the titer for FV viremia was determined using the Mus dunni focal infectivity assay. The dashed line corresponds to the assay's 600-FFU/ml cutoff. (C) Persistent splenomegaly in (B6 × BALB/c)F1 mice regardless of Apobec3 status. Spleens from (B6 Apobec3+/+ × BALB/c)F1 and (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice were harvested at 28 dpi and weighed. A normal mouse spleen would weigh <150 mg. (D) B6 Apobec3 deficiency is associated with higher spleen infectious centers at 28 dpi. Spleens from both cohorts were disaggregated at 28 dpi, and splenocytes were subjected to the Mus dunni assay. The number of focus-forming units or infectious centers was normalized for the whole spleen. In panels B to D, the mean values are highlighted with solid lines. The values were compared using a two-tailed Student's t test, with exact P values being noted.

It has also been shown that Rfv3 controls virus production by leukemic cells late in FV infection by antibody-mediated down-modulation of cell surface envelope glycoprotein (4, 12). Since the ability of infected cells to produce infectious centers in the focal immunofluorescence assay is dependent on high virus production (11), Rfv3s/s mice exhibit higher levels of infectious centers than Rfv3r/s mice even if they contain similar numbers of infected cells. Such an effect is exactly what was observed in the surviving (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice compared to (B6 Apobec3+/+ × BALB/c)F1 mice at 28 dpi. As expected for these F1 mice, the incidence of leukemia, as measured by gross splenomegaly at 28 dpi, was very high (Fig. 2C). Of note, the numbers of infectious centers were significantly higher in the (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice than (B6 Apobec3+/+ × BALB/c)F1 mice (Fig. 2D). These findings were again consistent with identity between Rfv3 and Apobec3.

Persistent viremia, splenomegaly, and cellular FV infection in (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice lacking the B6 Apobec3 allele.

Plasma viremia from more resistant (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice at 28 dpi was measured using the standard focal infectivity assay in Mus dunni cells (37). However, the levels in most of the samples were at or below the limit of detection (600 FFU/ml; data not shown), so a more sensitive quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) assay was employed (20). Viral RNA quantification of an FV stock with known titer in the Mus dunni assay revealed that 1 focus-forming unit corresponded to approximately 16,000 viral RNA copies (or roughly 8,000 viral particles). Viral RNA was extracted from plasma samples from (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A.BY)F1 and (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice at 28 dpi and subjected to the qRT-PCR assay. Surprisingly, both cohorts exhibited substantial plasma viremia (Fig. 3A). However, the increased sensitivity of this assay allowed us to demonstrate that B6 Apobec3 deficiency impaired recovery from viremia in (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice, where a 121-fold higher plasma viral load was observed at 28 dpi compared to that in wild-type F1 animals (Fig. 3A).

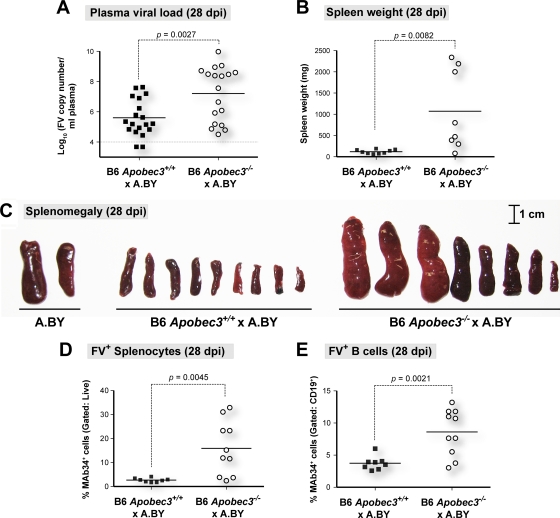

FIG. 3.

Apobec3 and recovery of (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice from viremia, splenomegaly, and cellular FV infection. (A) Impaired plasma viremia recovery in (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice. The numbers of viral RNA copies in plasma samples obtained at 28 dpi were determined by TaqMan real-time PCR and expressed as log10 values. The values from two independent cohorts were combined. The gray dotted line corresponds to the assay limit of detection (104 copies/ml). (B) Spleen weights at 28 dpi. (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A.BY)F1 mice exhibited higher spleen weights. (C) Splenomegaly in (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice at 28 dpi. Spleens from FV-infected (140 SFFUs) (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice are larger than those from (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A.BY)F1 mice. As a reference, two spleens obtained from A.BY mice at 28 dpi are shown. A normal, uninfected (B6 × A.BY)F1 mouse spleen would roughly correspond to the smallest spleen in this panel. (D) Cellular FV infection levels in (B6 × A.BY)F1 spleens at 28 dpi. FV+ splenocytes were detected using MAb 34, a monoclonal antibody against a cell surface FV antigen, Glyco-Gag. B6 Apobec3 deficiency resulted in significantly higher FV infection of total splenocytes. (E) Splenic B cells were significantly more infected in the absence of B6 Apobec3. In the relevant graphs, means were highlighted with a solid line. Values were compared using a two-tailed Student's t test, with exact P values being noted.

In contrast to (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A.BY)F1 mice, (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice also did not recover from splenomegaly at 28 dpi. The mean spleen weights in these animals were 9.0-fold higher (P = 0.0082) (Fig. 3B) and the spleens were grossly enlarged in comparison to the findings for (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A.BY)F1 mice (Fig. 3C). As expected, flow cytometric studies revealed that the percentage of FV-positive splenocytes from (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice at 28 dpi was 5.9-fold higher than that from (B6 Apobec3+/+ × A.BY)F1 mice (Fig. 3D), translating to about a 53-fold higher level of cellular FV infection when splenic size was accounted for. Subpopulation analysis revealed that these changes were accompanied by significantly increased infection of splenic erythroblasts (data not shown) and B cells at 28 dpi (Fig. 3E). Thus, Apobec3 was critical for recovery from both splenomegaly and cellular FV infection in BAFF-R-sufficient (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice.

Decreased total Apobec3 mRNA levels and aberrant mRNA splicing correlate with Rfv3 susceptibility.

We previously reported that Rfv3 susceptibility correlated with aberrant Apobec3 mRNA splicing in splenocytes (42). In addition to full-length Apobec3 transcripts, we cloned aberrantly spliced Apobec3 mRNA transcripts lacking exon 2 from BALB/c and A.BY mice that resulted in a frameshift mutation. On the other hand, no Δ2 transcripts were found in B6 mice, which predominantly expressed Apobec3 mRNA transcripts lacking exon 5. In contrast to Δ2 transcripts, the Δ5 transcripts encode a fully functional protein (1, 5, 33, 42, 46). We did not detect any significant difference in total mRNA levels between B6, A.BY, and BALB/c strains (42). However, shortly after publication of our report, the Neuberger, Ross, and Miyazawa groups reported that B6 mice expressed significantly higher total Apobec3 mRNA levels in the spleen than BALB/c (23, 33, 46) and A/WySn (46) strains. Reinspection of the original data set (42) revealed inaccurate interpolation of Apobec3 levels that were multiplied with incorrectly computed beta-actin normalization values. When the same data set was reanalyzed by interpolating from an in-plate best-fit standard curve (r2 > 0.98), mRNA levels were higher in B6 mice than in A.BY and BALB/c mice (data not shown).

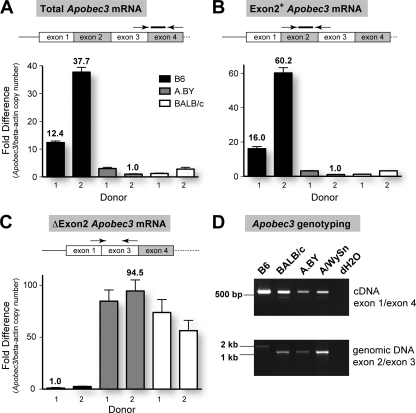

To further confirm this reanalysis, we extracted samples from two new donors from each strain and utilized newly designed Apobec3 primer sets and TaqMan probes. Consistent with subsequent observations and contrary to our initial result, B6 mice expressed up to 38-fold more Apobec3 mRNA in spleen than BALB/c or A.BY mice, using primers designed in exons 3 and 4 (Fig. 4A). Using exon 2-specific primers and probe, we observed even higher fold differences, with B6 mice expressing up to 60-fold more Apobec3 mRNA than BALB/c and A.BY mice (Fig. 4B). Of note, Apobec3 mRNA levels in the two donors tested for each strain vary by 2.2- to 3.7-fold using either primer pair, but this intrastrain variation is still substantially lower than the mean 19.4-fold difference between B6 mice and BALB/c or A.BY mice.

FIG. 4.

Apobec3 mRNA levels and aberrant splicing correlates with the Rfv3 phenotype. Total RNA was extracted from the spleens of Rfv3 resistant B6 and Rfv3 susceptible A.BY and BALB/c mice (two donors each) and reverse transcribed using random hexamers. cDNAs were subjected to multiple real-time PCR analyses, and beta-actin levels were determined for normalization of input cDNA. Serial 10-fold dilutions of plasmid standards with known copy numbers were included in each reaction plate to compute quantities. (A) Rfv3 susceptibility correlates with decreased Apobec3 mRNA levels. The ratios of Apobec3/beta-actin copy numbers were normalized against the lowest value (A.BY donor 2). B6 mice show higher total Apobec3 mRNA expression than A.BY and BALB/c mice. (B) Enrichment of Exon2+ Apobec3 transcripts in B6 mice. Compared to the data in panel A, the fold difference between the B6 and the Rfv3 susceptible strains using this primer set was higher. This would suggest that the total mRNA pool in Rfv3 susceptible strains contains transcripts lacking exon 2. (C) Detection of Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts in Rfv3 susceptible strains. Using a forward primer in the exon 1/exon 3 junction, Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts were amplified up to 95-fold more efficiently in A.BY and BALB/c mice than in B6 mice, despite having lower total Apobec3 levels. In all panels, arrows and lines correspond to primers and probes, with their relative locations being highlighted. Note that for panel A, the forward primer crosses the exon 3/exon 4 junction, while in panel B, the reverse primer crosses the exon 2/exon 3 junction. Error bars correspond to standard deviations in triplicate determinations. (D) Detection of transcripts with an exon 2 deletion correlate with a corresponding intronic deletion in Apobec3. (Upper panel) Amplification of cDNA using primers on Apobec3 exons 1 and 4 reveals a smaller product consistent with exon 2 deletion (148 bp) in BALB/c, A.BY, and A/WySn mice. While Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts have been previously cloned from A.BY mouse cDNA (42), the A.BY Δ2 product is faint due to lower overall amplification signal. (Lower panel) The genomic region spanning exons 2 and 3 was smaller for BALB/c, A.BY, and A/WySn mice, consistent with the lack of a 531-bp X-MLV LTR insertion in these strains.

The higher fold difference in Apobec3 levels using primers located in exon 2 could be explained by the existence of Apobec3 transcripts that lack exon 2, which were readily cloned from BALB/c and A.BY strains in our previous study (42). In fact, normalizing for beta-actin levels, primers specific for Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts resulted in significant amplification signals in A.BY and BALB/c strains in contrast to the signals in B6 mice (Fig. 4C), despite the fact that the A.BY and BALB/c strains had significantly lower total Apobec3 mRNA expression (Fig. 4A). The existence of Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts was confirmed by amplifying cDNA samples with primers spanning exon 2 (Fig. 4D, upper panel). In contrast to Exon2+ transcripts, Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts represent only a small subset of the mRNA pool in Rfv3 susceptible mice and could be missed if the overall amplification signal is suboptimal (Fig. 4D, upper panel, A.BY sample). Thus, in the context of reduced total Apobec3 mRNA expression, the relative levels of Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts detected in Rfv3 susceptible mice are unlikely to significantly influence the Rfv3 phenotype. In fact, Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts may be rapidly degraded (see Discussion).

Recently, a comprehensive study by Kozak and colleagues reported that B6 and other mouse strains encode a 531-bp genomic xenotropic murine leukemia virus (X-MLV) insertion at the exon 2 splice donor site of Apobec3 that is associated with increased Apobec3 mRNA levels (43). We confirmed this insertion in B6 mice but not BALB/c mice by sizing amplicons following PCR amplification with exon 2/exon 3 primers (Fig. 4D, lower panel) and DNA sequencing (data not shown). Importantly, A.BY and A/WySn mice also did not harbor this retroviral insertion (Fig. 4D, lower panel). Thus, in contrast to BAFF-R polymorphisms, decreased Apobec3 mRNA expression, aberrant splicing of Apobec3 exon 2, and the lack of an X-MLV insertion in the Apobec3 in the exon 2 splice donor site correlated perfectly with Rfv3 susceptibility (Table 2 ).

TABLE 2.

BAFFR versus Apobec3 polymorphisms in relation to Rfv3

| Strain | Rfv3 genotype | % spleen B cells | BAFF-R IAP insertiona | BAFF-R | Apobec3 mRNA levelsb | Apobec3 splicingc | Apobec3 X-MLV insertiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6 | r/r | Normal | Absent | Functional | High | Δ5 | Present |

| A/WySn | s/s | Reduced | Present | Defective | Low | FL, Δ2e | Absente |

| A.BY | s/s | Normal | Absent | Functional | Low | FL, Δ2 | Absente |

| BALB/c | s/s | Normal | Absent | Functional | Low | FL, Δ2 | Absent |

The IAP insertion results in replacement of the C-terminal 8 residues of BAFF-R with 21 novel amino acids (2, 47, 50).

Δ5 is the dominant form in B6 (1, 5, 23, 33, 42); full-length (FL) transcripts are more abundant in the other strains (7, 33; this study).

Corresponds to a 531-bp retroviral insertion between exons 2 and 3 of the Apobec3 genomic region (43).

Determined by sizing amplicons following PCR of genomic DNA or cDNA with exon-specific primers (this study).

DISCUSSION

The molecular identity of the Rfv3 gene, which controls viremia, virus-neutralizing antibody responses, and recovery from Friend retrovirus infection (10, 14), is of great interest to anyone trying to understand immune responses to retroviral infections. The recent report that Rfv3 was encoded by Apobec3 (42), a deoxycytidine deaminase that can restrict a broad range of retroviruses, including HIV-1, generated substantial interest and highlighted the general relevance of FV studies to retroviral immunology. However, the role of Apobec3 in Rfv3-mediated recovery from FV viremia and disease was recently challenged following the realization that one of the critical strains used in defining and mapping Rfv3, A/WySn, displayed a genetic defect in BAFF-R, a gene linked to Rfv3 (48).

The BAFF-R mutation caused by an IAP retroelement insertion results in severe B-cell maturation and survival defects in A/WySn mice (2, 28). There is no argument that this mutation can affect FV-induced NAb development and recovery from viremia and disease in this strain. However, the strain distribution for Rfv3 susceptibility includes the A.BY and BALB strains (10), both of which express functional BAFF-R, as demonstrated here by genetic and B-cell immunophenotyping methods. Thus, by analyzing key strains used to originally define Rfv3, we show that the BAFF-R polymorphism and its consequent impact on B-cell homeostasis are not well correlated with the Rfv3 phenotype (Table 2).

The study by Tsuji-Kawahara et al. (48) also questioned whether B6 Apobec3 deficiency results in increased viremia at 28 dpi, as previously reported for Rfv3 susceptible mice. Analysis of Apobec3 deficiency in both the (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 and (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 genetic backgrounds demonstrated significantly increased viremia at day 28 in the absence of the B6 Apobec3 gene. Although B6 Apobec3 deficiency resulted in increased mortality in (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice, the surviving mice displayed significantly increased levels of viremia at 28 dpi. Increased viremia was also detected in the more resistant (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice using a qRT-PCR assay. In addition, B6 Apobec3 deficiency in (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice also significantly impaired recovery from cellular FV infection and splenomegaly, making these normally resistant F1 mice more susceptible to FV-induced leukemia. The failure of the B6 Apobec3−/− mice to provide a transcomplementing Rfv3 resistance gene in F1 crosses to either A.BY or BALB/c provides strong evidence that Apobec3 encodes Rfv3, as previously concluded (42, 46).

Further evidence that Apobec3 encodes Rfv3 stems from the correlation between Apobec3 mRNA levels and the Rfv3 strain distribution. Previous reports from the Neuberger, Ross, and Miyazawa groups show that Rfv3 susceptible strains BALB (23, 33, 46) and/or A/WySn (46) exhibit Apobec3 mRNA levels that are significantly lower than those in Rfv3 resistant C57BL strains (Table 2). Revisiting these experiments, we now concur with these observations. To extend these findings, we also attempted to generate a polyclonal antibody against mouse Apobec3. However, three attempts in rabbits and chickens (Pocono Rabbit Farm, Canadensis, PA; Aves Labs, Tigard, OR; SDIX, Newark, DE) have failed to generate a suitable antiserum. A commercially available anti-mouse Apobec3 antibody (catalogue no. 07-0723; Millipore, Billerica, MA) also did not recognize overexpressed Apobec3. The impact of increased mRNA levels on endogenous Apobec3 protein levels therefore remains to be determined. However, at least for the human homologue Apobec3G, there is good concordance between mRNA and protein levels in primary cells (35).

The molecular basis for the higher expression of Apobec3 mRNA in B6 mice than in BALB/c, A.BY, and A/WySn mice remains unclear, but a recent study linked this phenomenon to an X-MLV insertion in the Apobec3 exon 2 splice donor site (43) (Fig. 4D). It was suggested that the long terminal repeat (LTR) region of this insertion may increase transcription levels through an enhancer effect and by affecting splicing (43). Notably, the absence of this retroviral insertion correlated with the detection of Apobec3 transcripts lacking exon 2 in Rfv3 susceptible mice by our group (42) as well as others (7, 33, 43) (Table 2). Apobec3 Δexon 2 transcripts result in a frameshift mutation, leading to a premature stop at the 36th codon (42). Premature termination codons due to aberrant splicing of cellular mRNAs are powerful signals for nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (16, 24, 29), suggesting that Apobec3 Δ2 transcripts may be rapidly degraded in Rfv3 susceptible mice. In other words, the X-MLV insertion at the Apobec3 exon 2 splice site in B6 mice may reduce or prevent aberrant mRNA splicing of exon 2, resulting in higher Apobec3 mRNA expression. If proven, this would indicate that retroviral insertions in this localized region in chromosome 15 were responsible for both positive (Apobec3) and negative (BAFF-R) effects on retroviral resistance. Of interest, mRNA transcripts from which exon 2 is deleted have also been detected in the human homologues, Apobec3G and Apobec3F (25). The potential role of alternative splicing in regulating endogenous levels of these biologically important restriction factors is currently being explored.

The B6 Apobec3 gene promotes the development of the FV-specific antibody and/or NAb response in inbred B6 mice and in outcrosses, including (B6 × BALB/c)F1, (B6 × A.BY)F1, and (B6 × A/WySn)F1 mice (42, 48). The results that we present in this report substantiate the notion that Apobec3-dependent enhancement of virus-specific antibody responses is critical for recovery from FV infection and disease. Thus, FV infection of mice with or without the B6 Apobec3 gene may provide important clues on the nature of a protective humoral immune response against a pathogenic retrovirus infection. However, not all genetic backgrounds may be useful for probing this question. Pure B6 mice do not develop splenomegaly due to an Fv2r/r genotype (Table 1), while the majority of (B6 Apobec3−/− × BALB/c)F1 mice do not survive to 28 dpi. These genetic backgrounds may therefore be more useful for exploring events surrounding acute FV infection. On the other hand, due to the codominant BAFF-R defect in A/WySn mice (31), the (B6 × A/WySn)F1 strain may be more relevant for retrovirus pathogenesis studies in B-cell-compromised hosts. (B6 × A.BY)F1 mice express functional BAFF-R, exhibit normal B-cell function, display susceptibility to FV infection, develop splenomegaly, and survive to 28 dpi, despite the absence of the B6 Apobec3 gene. We have therefore adopted the (B6 × A.BY)F1 strain to probe how the B6 Apobec3 gene influences FV-specific humoral immunity.

To date, our studies in the (B6 × A.BY)F1 background suggest that two events likely synergize to weaken NAb responses in (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice. These include (i) delayed induction of germinal center B cells and plasmablasts and increased hypergammaglobulinemia during acute infection (40) and (ii) progressive B-cell infection in the context of splenomegaly (Fig. 3). The Miyazawa group also reported increased B-cell activation and delayed B-cell maturation in (B6 Apobec3−/− × A/WySn)F1 mice during acute infection (48). In both studies (40, 48), the B6 Apobec3 gene protected B cells from acute FV infection. Thus, FV infection could directly alter B-cell function, leading to weaker NAb responses. The consequences of FV infection on antigen-specific B-cell development and function are currently being investigated.

Since FV infects B cells and HIV-1 does not, the relevance of the Apobec3/Rfv3 phenotype toward improving HIV-1-specific humoral immunity may be difficult to reconcile. However, it should be noted that CD4+ T cells, the primary targets of HIV-1 infection, are critical for antigen-specific B-cell development (30). In germinal centers, which are the primary sites for affinity maturation, antigen-specific B cells form direct conjugates with CD4+ T cells (36). Acute HIV-1 infection is associated with germinal center destruction, primarily in mucosal compartments (26). Thus, the relevance of the Apobec3/Rfv3 phenotype for HIV-1 infection has more to do with reducing similar virus-induced pathological events that precede weaker NAb development than with protecting identical cell types from infection. Documenting the sequence of events that result in poor NAb responses in (B6 Apobec3−/− × A.BY)F1 mice and testing therapeutic interventions to halt or reverse this pathological course by inducing the expression of the A.BY Apobec3 gene may provide critical insights on modulating human Apobec3G/Apobec3F expression levels in CD4+ T cells and improving humoral immunity against HIV-1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R56 AI-0841230 and R01 AI090795 (to M.L.S.) and R01 A065329 (to W.C.G.).

We thank Brent Palmer and Michelle Dsouza (University of Colorado Denver) and Jason Neidleman (GIVI) for flow cytometry assistance and Jeffrey Wilusz (Colorado State University) for discussions of alternative splicing and mRNA decay.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 October 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abudu, A., A. Takaori-Kondo, T. Izumi, K. Shirakawa, M. Kobayashi, A. Sasada, K. Fukunaga, and T. Uchiyama. 2006. Murine retrovirus escapes from murine APOBEC3 via two distinct novel mechanisms. Curr. Biol. 16:1565-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amanna, I. J., J. P. Dingwall, and C. E. Hayes. 2003. Enforced bcl-xL gene expression restored splenic B lymphocyte development in BAFF-R mutant mice. J. Immunol. 170:4593-4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck, J. A., S. Lloyd, M. Hafezparast, M. Lennon-Pierce, J. T. Eppig, M. F. Festing, and E. M. Fisher. 2000. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat. Genet. 24:23-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Britt, W. J., and B. Chesebro. 1983. Use of monoclonal anti-gp70 antibodies to mimic the effects of the Rfv-3 gene in mice with Friend virus-induced leukemia. J. Immunol. 130:2363-2367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browne, E. P., and D. R. Littman. 2008. Species-specific restriction of apobec3-mediated hypermutation. J. Virol. 82:1305-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cariappa, A., M. Tang, C. Parng, E. Nebelitskiy, M. Carroll, K. Georgopoulos, and S. Pillai. 2001. The follicular versus marginal zone B lymphocyte cell fate decision is regulated by Aiolos, Btk, and CD21. Immunity 14:603-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casey, R. E. 2006. Mouse strain-specific splicing of Apobec3. M.Sc. thesis. Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA. http://www.wpi.edu/Pubs/ETD/Available/etd-082206-113216/unrestricted/Casey.pdf.

- 8.Chesebro, B., W. Britt, L. Evans, K. Wehrly, J. Nishio, and M. Cloyd. 1983. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies reactive with murine leukemia viruses: use in analysis of strains of Friend MCF and Friend ecotropic murine leukemia virus. Virology 127:134-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesebro, B., M. Miyazawa, and W. J. Britt. 1990. Host genetic control of spontaneous and induced immunity to Friend murine retrovirus infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8:477-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesebro, B., and K. Wehrly. 1979. Identification of a non-H-2 gene (Rfv-3) influencing recovery from viremia and leukemia induced by Friend virus complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:425-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chesebro, B., and K. Wehrly. 1978. Rfv-1 and Rfv-2, two H-2-associated genes that influence recovery from Friend leukemia virus-induced splenomegaly. J. Immunol. 120:1081-1085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, D. Doig, and J. Nishio. 1979. Antibody-induced modulation of Friend virus cell surface antigens decreases virus production by persistent erythroleukemia cells: influence of the Rfv-3 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 76:5784-5788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, and J. Stimpfling. 1974. Host genetic control of recovery from Friend leukemia virus-induced splenomegaly: mapping of a gene within the major histocompatibility complex. J. Exp. Med. 140:1457-1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doig, D., and B. Chesebro. 1979. Anti-Friend virus antibody is associated with recovery from viremia and loss of viral leukemia cell-surface antigens in leukemic mice. Identification of Rfv-3 as a gene locus influencing antibody production. J. Exp. Med. 150:10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friend, C. 1957. Cell-free transmission in adult Swiss mice of a disease having the character of a leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 105:307-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garneau, N. L., J. Wilusz, and C. J. Wilusz. 2007. The highways and byways of mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8:113-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorelik, L., A. H. Cutler, G. Thill, S. D. Miklasz, D. E. Shea, C. Ambrose, S. A. Bixler, L. Su, M. L. Scott, and S. L. Kalled. 2004. Cutting edge: BAFF regulates CD21/35 and CD23 expression independent of its B cell survival function. J. Immunol. 172:762-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasenkrug, K. J., and U. Dittmer. 2007. Immune control and prevention of chronic Friend retrovirus infection. Front. Biosci. 12:1544-1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasenkrug, K. J., A. Valenzuela, V. A. Letts, J. Nishio, B. Chesebro, and W. N. Frankel. 1995. Chromosome mapping of Rfv3, a host resistance gene to Friend murine retrovirus. J. Virol. 69:2617-2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He, J. Y., H. J. Cheng, Y. F. Wang, Y. T. Zhu, and G. Q. Li. 2008. Development of a real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR assay for detection of the Friend leukemia virus load in murine plasma. J. Virol. Methods 147:345-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoag, K. A., K. Clise-Dwyer, Y. H. Lim, F. E. Nashold, J. Gestwicki, M. P. Cancro, and C. E. Hayes. 2000. A quantitative-trait locus controlling peripheral B-cell deficiency maps to mouse chromosome 15. Immunogenetics 51:924-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanari, Y., M. Clerici, H. Abe, H. Kawabata, D. Trabattoni, S. L. Caputo, F. Mazzotta, H. Fujisawa, A. Niwa, C. Ishihara, Y. A. Takei, and M. Miyazawa. 2005. Genotypes at chromosome 22q12-13 are associated with HIV-1-exposed but uninfected status in Italians. AIDS 19:1015-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langlois, M. A., K. Kemmerich, C. Rada, and M. S. Neuberger. 2009. The AKV murine leukemia virus is restricted and hypermutated by mouse APOBEC3. J. Virol. 83:11550-11559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lareau, L. F., A. N. Brooks, D. A. Soergel, Q. Meng, and S. E. Brenner. 2007. The coupling of alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 623:190-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lassen, K. G., S. Wissing, M. A. Lobritz, M. Santiago, and W. C. Greene. 2010. Identification of two APOBEC3F splice variants displaying HIV-1 antiviral activity and contrasting sensitivity to Vif. J. Biol. Chem. 285:29326-29335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levesque, M. C., M. A. Moody, K. K. Hwang, D. J. Marshall, J. F. Whitesides, J. D. Amos, T. C. Gurley, S. Allgood, B. B. Haynes, N. A. Vandergrift, S. Plonk, D. C. Parker, M. S. Cohen, G. D. Tomaras, P. A. Goepfert, G. M. Shaw, J. E. Schmitz, J. J. Eron, N. J. Shaheen, C. B. Hicks, H. X. Liao, M. Markowitz, G. Kelsoe, D. M. Margolis, and B. F. Haynes. 2009. Polyclonal B cell differentiation and loss of gastrointestinal tract germinal centers in the earliest stages of HIV-1 infection. PLoS Med. 6:e1000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilly, F. 1970. Fv-2: identification and location of a second gene governing the spleen focus response to Friend leukemia virus in mice. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 45:163-169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayne, C. G., I. J. Amanna, and C. E. Hayes. 2009. Murine BAFF-receptor residues 168-175 are essential for optimal CD21/35 expression but dispensable for B cell survival. Mol. Immunol. 47:590-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McGlincy, N. J., and C. W. Smith. 2008. Alternative splicing resulting in nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: what is the meaning of nonsense? Trends Biochem. Sci. 33:385-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHeyzer-Williams, L. J., N. Pelletier, L. Mark, N. Fazilleau, and M. G. McHeyzer-Williams. 2009. Follicular helper T cells as cognate regulators of B cell immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21:266-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller, D. J., and C. E. Hayes. 1991. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of a unique B lymphocyte deficiency in strain A/WySnJ mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 21:1123-1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyazawa, M., S. Tsuji-Kawahara, and Y. Kanari. 2008. Host genetic factors that control immune responses to retrovirus infections. Vaccine 26:2981-2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okeoma, C. M., J. Petersen, and S. R. Ross. 2009. Expression of murine APOBEC3 alleles in different mouse strains and their effect on mouse mammary tumor virus infection. J. Virol. 83:3029-3038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Portis, J. L., F. J. McAtee, and S. C. Kayman. 1992. Infectivity of retroviral DNA in vivo. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 5:1272-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Refsland, E. W., M. D. Stenglein, K. Shindo, J. S. Albin, W. L. Brown, and R. S. Harris. 2010. Quantitative profiling of the full APOBEC3 mRNA repertoire in lymphocytes and tissues: implications for HIV-1 restriction. Nucleic Acids Res. 38:4274-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reinhardt, R. L., H. E. Liang, and R. M. Locksley. 2009. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat. Immunol. 10:385-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson, M. N., M. Miyazawa, S. Mori, B. Caughey, L. H. Evans, S. F. Hayes, and B. Chesebro. 1991. Production of monoclonal antibodies reactive with a denatured form of the Friend murine leukemia virus gp70 envelope protein: use in a focal infectivity assay, immunohistochemical studies, electron microscopy and Western blotting. J. Virol. Methods 34:255-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robertson, S. J., C. G. Ammann, R. J. Messer, A. B. Carmody, L. Myers, U. Dittmer, S. Nair, N. Gerlach, L. H. Evans, W. A. Cafruny, and K. J. Hasenkrug. 2008. Suppression of acute anti-Friend virus CD8+ T-cell responses by coinfection with lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus. J. Virol. 82:408-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rowland, S. L., K. F. Leahy, R. Halverson, R. M. Torres, and R. Pelanda. 2010. BAFF receptor signaling aids the differentiation of immature B cells into transitional B cells following tonic BCR signaling. J. Immunol. 185:4570-4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santiago, M. L., R. L. Benitez, M. Montano, K. J. Hasenkrug, and W. C. Greene. 2010. Innate retroviral restriction by Apobec3 promotes antibody affinity maturation in vivo. J. Immunol. 185:1114-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santiago, M. L., and W. C. Greene. 2008. The role of the Apobec3 family of cytidine deaminases in innate immunity, G-to-A hypermutation and evolution of retroviruses, p. 183-206. In E. Domingo, C. R. Parrish, and J. J. Holland (ed.), Origin and evolution of viruses. Academic Press, London, United Kingdom.

- 42.Santiago, M. L., M. Montano, R. Benitez, R. J. Messer, W. Yonemoto, B. Chesebro, K. J. Hasenkrug, and W. C. Greene. 2008. Apobec3 encodes Rfv3, a gene influencing neutralizing antibody control of retrovirus infection. Science 321:1343-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanville, B., M. A. Dolan, K. Wollenberg, Y. Yan, C. Martin, M. L. Yeung, K. Strebel, A. Buckler-White, and C. A. Kozak. 2010. Adaptive evolution of Mus Apobec3 includes retroviral insertion and positive selection at two clusters of residues flanking the substrate groove. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1000974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stryke, D., M. Kawamoto, C. C. Huang, S. J. Johns, L. A. King, C. A. Harper, E. C. Meng, R. E. Lee, A. Yee, L. L'Italien, P. T. Chuang, S. G. Young, W. C. Skarnes, P. C. Babbitt, and T. E. Ferrin. 2003. BayGenomics: a resource of insertional mutations in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:278-281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Super, H. J., K. J. Hasenkrug, S. Simmons, D. M. Brooks, R. Konzek, K. D. Sarge, R. I. Morimoto, N. A. Jenkins, D. J. Gilbert, N. G. Copeland, W. Frankel, and B. Chesebro. 1999. Fine mapping of the Friend retrovirus resistance gene, Rfv3, on mouse chromosome 15. J. Virol. 73:7848-7852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeda, E., S. Tsuji-Kawahara, M. Sakamoto, M. A. Langlois, M. S. Neuberger, C. Rada, and M. Miyazawa. 2008. Mouse APOBEC3 restricts Friend leukemia virus infection and pathogenesis in vivo. J. Virol. 82:10998-11008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson, J. S., S. A. Bixler, F. Qian, K. Vora, M. L. Scott, T. G. Cachero, C. Hession, P. Schneider, I. D. Sizing, C. Mullen, K. Strauch, M. Zafari, C. D. Benjamin, J. Tschopp, J. L. Browning, and C. Ambrose. 2001. BAFF-R, a newly identified TNF receptor that specifically interacts with BAFF. Science 293:2108-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsuji-Kawahara, S., T. Chikaishi, E. Takeda, M. Kato, S. Kinoshita, E. Kajiwara, S. Takamura, and M. Miyazawa. 2010. Persistence of viremia and production of neutralizing antibodies differentially regulated by polymorphic APOBEC3 and BAFF-R loci in Friend virus-infected mice. J. Virol. 84:6082-6095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waterston, R. H., K. Lindblad-Toh, E. Birney, J. Rogers, J. F. Abril, P. Agarwal, R. Agarwala, R. Ainscough, M. Alexandersson, P. An, S. E. Antonarakis, J. Attwood, R. Baertsch, J. Bailey, K. Barlow, S. Beck, E. Berry, B. Birren, T. Bloom, P. Bork, M. Botcherby, N. Bray, M. R. Brent, D. G. Brown, S. D. Brown, C. Bult, J. Burton, J. Butler, R. D. Campbell, P. Carninci, S. Cawley, F. Chiaromonte, A. T. Chinwalla, D. M. Church, M. Clamp, C. Clee, F. S. Collins, L. L. Cook, R. R. Copley, A. Coulson, O. Couronne, J. Cuff, V. Curwen, T. Cutts, M. Daly, R. David, J. Davies, K. D. Delehaunty, J. Deri, E. T. Dermitzakis, C. Dewey, N. J. Dickens, M. Diekhans, S. Dodge, I. Dubchak, D. M. Dunn, S. R. Eddy, L. Elnitski, R. D. Emes, P. Eswara, E. Eyras, A. Felsenfeld, G. A. Fewell, P. Flicek, K. Foley, W. N. Frankel, L. A. Fulton, R. S. Fulton, T. S. Furey, D. Gage, R. A. Gibbs, G. Glusman, S. Gnerre, N. Goldman, L. Goodstadt, D. Grafham, T. A. Graves, E. D. Green, S. Gregory, R. Guigo, M. Guyer, R. C. Hardison, D. Haussler, Y. Hayashizaki, L. W. Hillier, A. Hinrichs, W. Hlavina, T. Holzer, F. Hsu, A. Hua, T. Hubbard, A. Hunt, I. Jackson, D. B. Jaffe, L. S. Johnson, M. Jones, T. A. Jones, A. Joy, M. Kamal, E. K. Karlsson, et al. 2002. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature 420:520-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan, M., J. R. Brady, B. Chan, W. P. Lee, B. Hsu, S. Harless, M. Cancro, I. S. Grewal, and V. M. Dixit. 2001. Identification of a novel receptor for B lymphocyte stimulator that is mutated in a mouse strain with severe B cell deficiency. Curr. Biol. 11:1547-1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]