Abstract

Introduction:

There is a general consensus that sleep disruption in children causes daytime behavioral deficits. It is unclear if sleep disruption in children with eczema has similar effects particularly after controlling for known comorbid disorders such as asthma and rhinitis.

Methods:

Parents of children (6-16 y) with eczema (n = 77) and healthy controls (n = 30) completed a validated omnibus questionnaire which included the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children, Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised (S), Child Health Questionnaire, Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index, and additional items assessing eczema, asthma, rhinitis, and demographics.

Results:

Compared to controls, children with eczema had a greater number of sleep problems with a greater percentage in the clinical range, lower quality of life, and higher levels of ADHD and oppositional behavior. They also had elevated rhinitis and asthma severity scores. Importantly, structural equation modelling revealed that the effect of eczema on the behavioral variables of Hyperactivity, ADHD Index, and Oppositional Behaviors were mediated through sleep with no direct effect of eczema on these behaviors. The comorbid atopic disorders of rhinitis and asthma also had independent effects on behavior mediated through their effects on sleep.

Conclusions:

The present findings suggest that the daytime behaviors seen in children with eczema are mediated independently by the effects of eczema, asthma, and rhinitis on sleep quality. These findings highlight the importance of sleep in eczematous children and its role in regulating daytime behavior.

Citation:

Camfferman D; Kennedy JD; Gold M; Martin AJ; Winwood P; Lushington K. Eczema, sleep, and behavior in children. J Clin Sleep Med 2010;6(6):581-588.

Keywords: Eczema, sleep, behavior, structural equation modelling, rhinitis, asthma

Eczema is a recurring, primarily non-infectious, inflammatory skin condition present in 10% to 20% of children in industrialized countries.1–8 Sleep disturbance is a common complaint in children with eczema, affecting up to 83% of children during eczema exacerbations.9–14 Sleep in children with eczema has been reported to be characterized by poor initiation,13,15,16 frequent awakenings,15,17–21 and prolonged nocturnal wakefulness.22 Poor sleep is known to be associated with a range of daytime deficits in healthy children.23–27 Behavioral problems have also been reported in children with eczema, including reduced child and family quality of life,14,16,28–33 increased discipline problems,15 and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).34,35 These findings raise the possibility that disturbed sleep caused by eczema may mediate the effect of eczema on daytime behavior.36,37 It is noteworthy that this relationship is complicated by the frequent co-occurrence of asthma and rhinitis in children with eczema.38 These atopies are also known to adversely impact sleep39,40 and are associated with behavioral deficits.41,42 In children with eczema, the relative contributions of eczema, rhinitis, and asthma to sleep disturbance and deficits in daytime behavior have yet to be examined.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the frequency of sleep problems in children with eczema compared to healthy controls and, after controlling for asthma and rhinitis, to evaluate its independent association with daytime behavior and quality of life.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Eczema is known to adversely affect daytime behavior. It is unclear whether this is a direct effect or mediated by the effect of eczema on sleep quality.

Study Impact: This study demonstrates that the effect of eczema on daytime behavior is mediated by its effect on sleep quality. This highlights the importance of the recognition and management of sleep problems in children with eczema.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

Parents of children (aged 6-16 y) attending allergy and dermatology clinics at the Women's and Children's Hospital, Adelaide, a tertiary referral center for the state of South Australia, were recruited into the study.

One hundred seven families with eczematous children were approached on clinic days over a 6-month period, with parents of 77 children with eczema volunteering for the study. An additional 18 healthy non-eczematous school friends of the eczema children and 12 non- eczematous children from a volunteer database maintained by our group were recruited as controls. Eczema subjects were diagnosed by the Medical Specialist attending allergy and dermatology clinics using standardized criteria.43 Control subjects reported no history of eczema.

Parents were asked to complete an omnibus questionnaire while attending the clinic. They were also asked to forward a questionnaire to the parents of a class friend of their child without eczema (18 controls). Children from the volunteer database who were of appropriate age and socioeconomic status were sequentially contacted by telephone and invited to participate in the study (12 controls). Children were excluded if they reported a history of craniofacial abnormalities, cleft palate, neurological disorder, muscular dystrophy, intellectual delay, developmental delay, or severe behavioral disorders. Residential postcode was used to estimate socioeconomic status based on the Australian Bureau of Statistics Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA).44

The study was approved by the Womens' and Children's Hospital Ethics committee and University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics committee.

Apparatus

General quality of life was assessed using the Child Health Questionnaire–Parent Form (CHQ-PF-28). Questionnaire items were rated using a 4-point frequency scale (1 “never” to 4 “always”), apart for the item “In general, how would you rate the child's health?” which rated the child on a 5-point severity scale (1 “very good” to 5 “poor”) and “How much bodily pain or discomfort has the child experienced in the last 12 months?” which was rated on a 4-point severity scale (1 “none” to 4 “severe”).45

The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI)46 was used to assess eczema severity and eczema quality of life. Parents were asked to rate on a 4-point scale (1 “not at all” to 4 “very much”) the impact of the child's skin disorder over the previous week on 10 quality of life indices. The CDLQI validity and reliability has been established through comparison with other eczema-specific instruments.47

Two 4-point items (1 “not at all” to 4 “very much”) from the CDLQI were used to specifically assess eczema severity (“Over the last week, how itchy, scratchy, sore or painful or has the child's skin been?”) and the impact of eczema on sleep (“Over the previous week how much has the child's sleep been affected by their skin problem?”). The following items from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase 1 Core questionnaire (ISAAC) were used to assess asthma severity (“How many attacks of wheezing has your child had in the last 12 months?” rated 1 “none” to 4 “more than 12”), impact of asthma on sleep (“How often, on average, has wheezing disturbed your child's sleep?” rated 1 “never woke with wheezing,” 2 “< 1 night per week,” and 3 “> 1 night per week”) and rhinitis prevalence (“In the last 12 months, has your child had a problem with sneezing or a runny or blocked nose when he/she did not have a cold or the flu?” rated yes/no), severity (“In which of the past 12 months did this nose problem occur?” January–December), and an additional author-designed question assessing the impact on sleep (“How often, on average, has your child been kept awake at night by this nose problem?” rated 1 “never,” 2 “< 1 night per week,” and 3 “> 1 night per week”).48

Sleep problems over the previous 12 months were assessed using the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC).49 The SDSC contains 2 items assessing sleep quality using a 5-point scale (total sleep time 1 “9-11 h” to 5 “< 5 h”; and latency to sleep onset 1 “< 15 min” to 5 “> 60 min”) and 24 items assessing the frequency of sleep disorder symptoms also rated on a 5-point scale (1 “never” to 5 “always”). The SDSC provides normed T-scores (mean 50, SD 10) for 6 scales entitled: disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep (e.g. sleep duration, sleep latency, night awakenings, and anxiety falling asleep), disorders of sleep breathing (e.g., snoring and breathing problems), disorders of arousal (e.g., sleepwalking, sleep terrors, and nightmares), disorders of sleep-wake transition (e.g., rhythmic movements, hypnic jerks, sleep talking, and bruxism), disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness (e.g., difficulty waking up, morning tiredness, and inappropriate napping), sleep hyperhidrosis (e.g. nocturnal sweating), and a composite total sleep problem score.49 The reliability and validity of the SDSC has been well evaluated and supported.49 Additional questions concerning the normal timing of sleep on weekdays and weekends were also collected.

Behavioral problems over the previous 12 months were assessed using the Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised (S).50 The scale contains 27 statements about the child's behavior rated on a 4-point scale (1 “not true at all” to 4 “very much true”) and provides T-score (mean 50, SD 10) based on an age and gender for 4 subscales: Oppositional Behavior (e.g., defiant, loses temper), Cognitive Problems (e.g., fails to complete assignments, not reading up to par), Hyperactivity (e.g., restless in the “squirmy” sense, excitable, impulsive), and an ADHD Index (e.g., short attention span, distractibility, or attention span a problem).50 This well-validated measure has been previously used to examine the relationship between child sleep and behavior.51–53

Statistics

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 16. An assessment of potential confounding factors between the eczema and control groups including age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, rhinitis, and the affects of asthma and rhinitis disturbing sleep were undertaken prior to analyses. Group differences were tested using either F-test or χ2 analyses where appropriate. Pearson-r correlations were used to assess the relationship between age and socioeconomic status and the impact of atopy on sleep in children with eczema. Structural equation modelling (SEM) analyses was undertaken to estimate the causal relationship between atopic disorders, sleep, and behavioral variables. SEM was selected, as it does not assume that independent variables are uncorrelated (eczema and sleep), and unlike liner regression (e.g., path analysis) it permits the relative contribution of all variables to be examined in the one model.

Preliminary analyses revealed that children with eczema reported significantly higher asthma and rhinitis severity scores and the frequency with which rhinitis disturbed sleep (see Table 1). No significant group differences were observed in gender, age, socioeconomic status, and the frequency with which asthma disturbed sleep. Accordingly, asthma severity, rhinitis severity, and frequency with which rhinitis disturbed sleep were entered as covariates in subsequent between group analyses.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) demographic, quality of life, sleep, and behavior questionnaire scores for children with eczema and controls together with F-test/χ2 results

| Mean (SD)/subject ratio |

F-test and χ2 results |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Eczema (n = 77) | Control (n = 30) | ||

| Demographics | |||

| Gender (male/female) | 33/44 | 17/13 | χ2 = 1.7 |

| Age (years) | 9.9 (2.8) | 9.8 (2.5) | F = 0.0 |

| Socioeconomic status | 996.5 (82.2) | 984.2 (84.7) | F = 0.5 |

| Atopic Disease | |||

| Eczema severity in the last week | 2.7 (0.9) | 1.0 (0.0) | F = 103.3***** |

| Asthma severity in the last 12 months | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.5 (0.8) | F = 5.5* |

| Rhinitis severity in the last 12 months | 5.6 (4.5) | 1.4 (3.0) | F = 22.3***** |

| Frequency | |||

| Asthma disturbing sleep in the last 12 months | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | F = 2.2 |

| Rhinitis disturbing sleep in the last 12 months | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.3) | F = 10.8*** |

| Medication | |||

| Taken by subjects for eczema | 65/77 (84%) | 0/30 (0%) | χ2 = 64.5***** |

| Taken by subjects for asthma | 44/77 (57%) | 10/30 (33%) | χ2 = 4.9* |

| 1Child-Health Questionnaire - Parent Form 28 (modified) | |||

| Sub-scales | |||

| Physical Functioning | 5.0 (2.0) | 3.8 (1.3) | F = 3.5 |

| Role/Social Emotional - Behavioral | 2.3 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.7) | F = 6.1* |

| Bodily Pain | 2.4 (0.9) | 1.6 (0.7) | F = 15.8***** |

| General Health Perceptions | 9.1 (2.0) | 7.7 (1.7) | F = 7.1** |

| Change in Health | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.6) | F = 9.6*** |

| Parental Impact – Emotional | 4.2 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.3) | F = 8.6*** |

| Family Activities | 3.5 (1.6) | 2.8 (1.0) | F = 1.7 |

| Family Cohesion | 1.9 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.7) | F = 4.6* |

| Total score | 30.3 (7.9) | 23.5 (5.1) | F = 10.7**** |

| 1Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index | |||

| Total score | 19.5 (7.5) | N/A | N/A |

| 1Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children | |||

| Disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep | 70.9 (18.1) | 58.1 (12.8) | F = 11.0*** |

| Disorders of sleep breathing | 59.0 (16.6) | 52.4 (10.7) | F = 0.1 |

| Disorders of arousal | 56.4 (14.4) | 55.4 (13.3) | F = 0.3 |

| Disorders of sleep wake transition | 63.0 (15.8) | 54.9 (13.2) | F = 2.9 |

| Disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness | 61.9 (17.4) | 50.2 (8.0) | F = 7.8** |

| Sleep hyperhidrosis | 52.2 (11.5) | 51.1 (10.8) | F = 0.1 |

| Total score | 70.7 (16.1) | 56.0 (11.0) | F = 12.5*** |

| 1Conners Parent Rating Scale – Revised (S) | |||

| Cognitive problems | 53.1 (9.9) | 49.9 (8.3) | F = 2.5 |

| Hyperactivity | 56.4 (12.6) | 50.6 (10.8) | F = 3.2 |

| ADHD Index | 55.1 (10.7) | 49.0 (8.9) | F = 8.2** |

| Oppositional Behavior | 57.4 (12.6) | 50.3 (8.6) | F = 8.0** |

NB

The following variables were co-varied for in the analyses; asthma severity, rhinitis severity and frequency with which rhinitis disturbed sleep.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.005

p < 0.001

p < 0.0005

N/A, not applicable.

RESULTS

Compared to controls, children with eczema had a lower general quality of life, more disturbed sleep with significantly higher scores on the Disorders of Initiating and Maintaining Sleep, Excessive Daytime Sleepiness, Total Sleep Disturbance scales and higher scores on the behavioral domains of ADHD Index and Oppositional Behaviors (see Table 1).

A higher percentage of children with eczema compared to controls were above the clinical cut-off criteria (T-score > 70) for Disorders of Initiating and Maintaining Sleep (42% [32/77] vs. 7% [2/30]), Disorders Of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (27% [21/77] vs. 7% [2/30]) and Total Sleep Problems (47% [36/77] vs. 10% [3/30]) and to a lesser extent for Disorders of Sleep Breathing (19% [15/77] vs. 10% [3/30]), Disorders of Arousal (23% [18/77] vs. 7% [2/30]), Sleep–Wake Transition Disorders (13% [10/77] vs. 10% [3/30]), and Sleep Hyperhidrosis (9% [7/77] vs. 7% [2/30]). Similarly, on the Conners Parent Rating Scale – Revised (S) a higher percentage of children with eczema were above the clinical cut-off in Oppositional Behavior (18% [14/77] vs. 0% [0/30]), ADHD Index (12% [9/77] vs. 7% [2/30]) and Cognitive Problems (6% [5/77] vs. 3% [1/30]), but no trends were noted in the Hyperactivity scale scores (10% [8/77] vs. 10% [3/30]).

There was a non-significant trend for children with eczema compared to controls to spend a longer time in bed on weekdays (mean [SD] = 10:37 (01:02) vs 10:13 (00:55) h: min) and weekends (10:39 [01:09] vs 10:29 [01:03] h:min).

Correlation Results

Younger age was associated with a higher frequency of disturbed sleep due to eczema in the last week (r = −0.33, p < 0.005) and last 12 months (r = −0.27, p < 0.05). By contrast no significant association was observed between age and frequency of disturbed sleep in the last 12 months due to either asthma (r = 0.12) or rhinitis (r = 0.22). Lower socioeconomic status was also associated with a higher frequency of disturbed sleep due to eczema in the last week (r = −0.26, p < 0.05) and last 12 months (−0.36, p < 0.005). Again, by contrast, no significant association was observed between socioeconomic status and frequency of disturbed sleep in the last 12 months due to either asthma (r = −0.05) or rhinitis (r = 0.01).

Structural Equation Modelling Analysis (SEM)

Based on an examination of the literature on outcomes of eczema, asthma, and rhinitis on sleep and behavioral outcomes, we developed SEM models of the interactions between Eczema, Asthma, Rhinitis, Sleep, and Cognitive Problems, Hyperactivity, ADHD Index, and Oppositional (behavior) separately using Amos 17 software.54

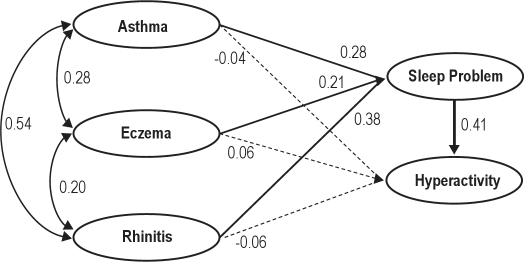

Figure 1 shows the (representative) hypothesized model of the effects of Asthma, Eczema, and Rhinitis on Cognitive Problems to be tested. Figure 1 indicates potential direct and indirect paths (through Sleep Problems) from each condition (Eczema, Asthma, and Rhinitis) to the behavioral outcomes of Cognitive Problems, Hyperactivity, ADHD Index, and Oppositional Behavior. All of these hypothesized Condition/Sleep Problem/Behavioral outcome models were successfully fitted to the data, and the final form of these models are shown in Figure 2a–d; Each comprises 3 exogenous variables i.e. variables which do not appear as a dependent variable in the model and 2 endogenous variables. Of the former, Asthma was operationalized by 2 indicators (items Rh1 and Rh2 from the questionnaire); i.e. “…has your child ever had wheezing or whistling in the chest?” and “…how many attacks of this have they had in the last 12 months?” Eczema was also operationalized by two items: “…has your child ever had eczema?” and “…has you child ever had an itchy rash which comes and goes for at least 6 months?” Rhinitis was operationalized by a single item ‘Rhinitis Total Score’ which is a sum of ratings of the child's nasal condition over the last 24 hours. Sleep Problems was operationalized by 6 indicators, which were the T-scores for 6 subscales of disorders of maintaining and initiating sleep, disorders of sleep breathing, disorders of arousal, disorders of sleep-wake transition, disorders of excessive daytime sleepiness and sleep hyperhidrosis from the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (T-scores represent scores converted to a 0-100 basis with a mean of 50). The outcome variables of “Cognitive Problems,” “Hyperactivity,” “ADHD Index,” and “Oppositional” (behaviors) were variously operationalized by the T-score total for each variable derived from the Conners Parent Rating Scale-Revised (S).

Figure 1.

SEM model for hypothesized relationships between conditions (3), sleep, & behaviors (4); variables, variable indicators and paths

M1 = Direct Effects, M2 = Indirect Effects (via Sleep)

Figure 2a.

Partial mediation ADHD by asthma, eczema and rhinitis on sleep

Dotted paths indicate statistically insignificant path coefficients. Default Model: CMIN/df = 1.31; CFI = 0.977; TL = 0.933; GFI = 0.934; RMSEA = 0.054. Independence Model: CMIN/df = 9.23; CFI = 0.0001; TLI = 0.0001; GFI = 0.524; RMSEA = 0.217

Figure 2b.

Partial mediation cognition by asthma, eczema and rhinitis on sleep

Default Model: CMIN/df = 1.37; CFI = 0.973; TL = 0.933; GFI = 0.955; RMSEA = 0.054. Independence Model: CMIN/df = 9.18; CFI = 0.0001; TLI = 0.0001; GFI = 0.523; RMSEA = 0.278

Figure 2c.

Partial mediation of hyperactivity by asthma, eczema, rhinitis on sleep

Default Model: CMIN/Df = 1.85, CFI = 0.942; TLI = 0.915; GFI = 0.900; RMSEA = 0.085. Independence Model: CMIN/df = 10.72; CFI = 0.0001; TLI = 0.0001; GFI = 0.554; RMSEA = 0.299

Figure 2d.

Partial mediation of opposition by asthma, eczema, rhinitis on sleep

Default Model: CMIN/df = 1.31; CFI = 0.978;TLI = 0.962; GFI = 0.934; RMSEA = 0.054. Independence Model: CMIN/df = 9.42; CFI = 0.0001; TLI = 0.0001; GFI = 0.507; RMSEA = 0.282

The fit of the models to the data was assessed with: the χ2 statistic, the goodness of fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA),55 comparative fit index (CFI)56 (correct), and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). For each of these statistics, values ≥ 0.90 are acceptable,57 except for the RMSEA for which values up to 0.08 indicate an acceptable fit of the model to the data.58

We first assessed direct effects models. Specifically, we tested the fit and significance of path coefficients of the direct effects: Asthma, Eczema, and Rhinitis → (Behavior) (M1 paths).

Table 2 indicates that M1 models fitted to the data poorly and that none of the path coefficients from (Condition) to (Behavior) were significant. However the path from (Sleep) to (Behavior) was statistically significant in each case except for the Cognitive Problems outcome variable.

Table 2.

Results of structural equation modelling (maximum likelihood estimates) for the total sample (n = 107) of relationship between asthma, eczema, and rhinitis on sleep problems, and behavior problems cognition

| χ2 | df | GFI | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | χ2 (df) difference/significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 Direct effect (medical) condition on cognition | 85.2 | 39 | 0.891 | 0.114 | 0.891 | 0.833 | |

| M1 Direct effects condition on hyperactivity | 77.7 | 36 | 0.900 | 0.105 | 0.907 | 0.858 | |

| M1 Direct effects condition on ADHD | 83.3 | 36 | 0.894 | 0.114 | 0.896 | 0.842 | |

| M1 Direct effects condition on opposition | 83.9 | 36 | 0.894 | 0.112 | 0.897 | 0.842 | |

| M2 Direct effects condition on cognition-(partial mediation by sleep) | 45.2 | 33 | 0.933 | 0.050 | 0.973 | 0.955 | (M1-M2) 40.06(3)*** |

| M2 Direct effects condition on hyperactivity-(partial mediation by sleep) | 38.0 | 33 | 0.940 | 0.038 | 0.989 | 0.985 | (M1-M2) 39.69 (3)*** |

| M2 Direct effects condition on ADHD-(partial mediation by sleep) | 43.4 | 33 | 0.934 | 0.054 | 0.967 | 0.962 | (M1-M2) 39.95(3)*** |

| M2 Direct effects condition on opposition-(partial mediation by sleep) | 43.2 | 33 | 0.938 | 0.054 | 0.978 | 0.963 | (M1-M2) 40.65 (3)*** |

| M3 Effects condition on cognition-(full mediation by sleep) | 46.8 | 36 | 0.931 | 0.053 | 0.971 | 0.963 | (M2-M3) -1.44 (0) ns |

| M3 Effects condition on hyperactivity-(full mediation by sleep) | 38.8 | 36 | 0.939 | 0.025 | 0.994 | 0.990 | (M2-M3) -0.53 (0) ns |

| M3 Effects condition on ADHD-(full mediation by sleep) | 46.9 | 36 | 0.923 | 0.054 | 0.976 | 0.963 | (M2-M3) -3.54 (0)* |

| M3 Effects condition on opposition-(full mediation by sleep) | 48.8 | 36 | 0.927 | 0.058 | 0.958 | 0.972 | (M2-M3) -5.56 (0)* |

p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

p < 0.005

df, degrees of freedom; GFI, goodness-of-fit index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; CFI, comparative fit index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; χ2, Chi-Square Statistic

We next tested the addition of paths from (Condition) to (Behavior) with paths from (Condition) to (Sleep) added, i.e. partial mediation of Condition by Sleep (M2 models). As reported in Table 2 these models fitted to the data very well. However, as with the direct effect (M1) models, no significant effects of Sleep on Cognitive Problems were evident.

The significance of the direct paths of (Condition) →(Sleep) permitted proceeding to testing full mediation of effects of (Condition) on (Behavior) through their effects of Sleep Problems (M3 models).59 As reported in Table 2, all M3 models had a good fit to the data, with effects in the expected direction. However χ2 difference tests revealed that all M3 models were worse than the M2 models, and in the case of ADHD Index and Oppositional Behavior, significantly worse than M2 models.

Given the association reported in children between eczema and sleep disordered breathing20 and, likewise, sleep disordered breathing and problematic behavior,60 we undertook additional analyses examining the contribution of sleep disordered breathing to the magnitude of the association between Sleep and Behavior. The removal of the item assessing Disorders of Sleep Breathing from Sleep Problems resulted in a small reduction in the magnitude of the path coefficients between Sleep and Behavior (ranging from 0.01 to 0.09), but not the overall pattern of significant associations.

In summary, the confirmatory factor analyses suggest that the three conditions—asthma, eczema, and rhinitis—have a significant effect on childhood behavioral outcomes including Hyperactivity, ADHD Index, and Oppositional Behavior. This effect is substantially, but not completely, mediated by the effects of these conditions on sleep problems. The greatest effect between Sleep Problems and behavioral outcomes was seen on Oppositional Behavior followed by Hyperactivity and least on ADHD. Surprisingly, no significant effect on Cognitive Problems was evident.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of the present study are that children with eczema compared to controls not only have a higher frequency of sleep and daytime behavioral deficits, but that the daytime behavior deficits are mediated through the effects that eczema has on sleep rather than the direct effects of eczema itself per se. There were also similar findings for asthma and rhinitis.

Consistent with earlier studies the sleep of children with eczema was characterized by problems with settling and maintaining sleep while their daytime functioning was characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and higher ADHD and Oppositional Behavior scores.10,11,15,61,62 Correlational analyses revealed that sleep disruption secondary to eczema was associated with higher Hyperactivity, ADHD Index, and Oppositional Behavior scores, and lower quality of life scores. By contrast, sleep disruption secondary to either asthma or rhinitis was not associated with behavioral deficits.

Structural equation modelling was used to test whether there was a direct casual relationship between eczema, asthma, rhinitis and daytime behavior (Cognitive Problems, Hyperactivity, ADHD Index, and Oppositional Behavior), or whether this relationship was mediated through sleep. Modelling revealed that the effects of eczema, asthma, and rhinitis on behavior were largely mediated through their respective effects on sleep. An examination of the magnitude of the path coefficients suggests that of the three atopic conditions, eczema had the weakest effect. As a corollary, given the high frequency of problematic behavior in children with sleep disordered breathing60 and the association between eczema and sleep disordered breathing in children20 we undertook additional analyses to assess the contribution of sleep disordered breathing to problematic behavior in children with eczema. The removal of sleep disorder breathing from the model resulted in a small reduction in the magnitude of path coefficients between sleep and behavior, but not the overall pattern of significant relationships. Incidentally, the clinical condition of eczema, once rhinitis and asthma have been allowed for, serves as the ideal model to determine the effect of sleep disturbance without hypoxia/obstruction on daytime behavior. The present findings suggest that sleep fragmentation alone is sufficient to explain behavioral deficits.

In the present study, children with eczema were more likely to report disturbed sleep if they were younger and of lower socioeconomic status. The age findings are consistent with Hon and colleagues who report reduced sleep quality in children with eczema aged < 10 compared to > 10 y.30 Low socioeconomic is reported to be a risk factor in children for sleep disordered breathing,63 but this is the first study to report a relationship between SES and sleep in children with eczema.

Consistent with previous research, eczema severity and sleep disturbance in children with eczema were found in this study to be associated with reduced quality of life. Sleep disturbance has been rated as the second highest contributing factor to reduced quality of life in children with eczema after itch,30 while parents with eczematous children report that is the most stressful aspect of care31,64 and rank sleep disturbance as the major impact on family quality of life.31,65

A limitation of the current study is the reliance on parental report. In future studies it would be desirable to verify sleep using objective measures such as polysomnography and obtain independent ratings of child behavior, for example from teachers.

In conclusion, disturbed sleep is common in children with more severe eczema and, moreover, mediates the effects of eczema on daytime behavior. The present findings raise the important question as to whether the effect of treatment of eczema will ameliorate nocturnal disturbance and thereby improve daytime behavioral deficits.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beasley R, Keil U, von Mutius E, Pearce N. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjuctivitis, and atopic eczema. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kay J, Gawkrodger DJ, Mortimer MJ, Jaron AG. The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:35–9. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(94)70004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp AS. Atopic eczema: its social and financial costs. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35:229–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robertson CF, Dalton MF, Peat JK, Haby MM, Bauman A, Kennedy JD, et al. Asthma and other atopic diseases in Australian children. Australian arm of the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood. Med J Aust. 1998;168:434–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson MLR, J . Prevelance of dermatologic disease among persons 1-74 years of age PH 5 79--1660 ed. United States. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control; US Dept. of Health, Education and Welfare publication; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, Andersen KE. Prevalence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and hand and contact dermatitis in adolescents. The Odense Adolescence Cohort Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:523–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darsow U, Laifaoui J, Kerschenlohr K, Wollenberg A, Przybilla B, Wuthrich B, et al. The prevalence of positive reactions in the atopy patch test with aeroallergens and food allergens in subjects with atopic eczema: a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2004;59:1318–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams H, Robertson C, Stewart A, Ait-Khaled N, Anabwani G, Anderson R, et al. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of symptoms of atopic eczema in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103:125–38. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fennessy M, Coupland S, Popay J, Naysmith K. The epidemiology and experience of atopic eczema during childhood: a discussion paper on the implications of current knowledge for health care, public health policy and research. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2000;54:581–9. doi: 10.1136/jech.54.8.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daud LR, Garralda ME, David TJ. Psychosocial adjustment in preschool children with atopic eczema. Arch Dis Child. 1993;69:670–6. doi: 10.1136/adc.69.6.670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson V, Lewis-Jones MS, Reid P, Owens RG, Finlay AY. Family impact of childhood atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 1995;133:19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long CC, Funnell CM, Collard R, Finlay AY. What do members of the National Eczema Society really want? Clin Exp Dermatol. 1993;18:516–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1993.tb01020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid P, Lewis-Jones MS. Sleep difficulties and their management in preschoolers with atopic eczema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:38–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chamlin SL, Cella D, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Mancini AJ, Lai JS, et al. Development of the Childhood Atopic Dermatitis Impact Scale: initial validation of a quality-of-life measure for young children with atopic dermatitis and their families. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:1106–11. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahl RE, Bernhisel-Broadbent J, Scanlon-Holdford S, Sampson HA, Lupo M. Sleep disturbances in children with atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:856–60. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170210030005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life of children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reuveni H, Chapnick G, Tal A, Tarasiuk A. Sleep fragmentation in children with atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:249–53. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartlet LB, Westbroek R, White JE. Sleep patterns in children with atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol. 1997;77:446–8. doi: 10.2340/0001555577446448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamlin SL, Mattson CL, Frieden IJ, Williams ML, Mancini AJ, Cella D, et al. The price of pruritus: sleep disturbance and cosleeping in atopic dermatitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:745–50. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chng SY, Goh DY, Wang XS, Tan TN, Ong NB. Snoring and atopic disease: a strong association. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38:210–6. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Emerson RM, Charman CR, Williams HC. The Nottingham Eczema Severity Score: preliminary refinement of the Rajka and Langeland grading. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:288–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stores G, Burrows A, Crawford C. Physiological sleep disturbance in children with atopic dermatitis: a case control study. Pediatr Dermatol. 1998;15:264–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1998.1998015264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart CN, Palermo TM, Rosen CL. Health-related quality of life among children presenting to a pediatric sleep disorders clinic. Behav Sleep Med. 2005;3:4–17. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0301_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokomaku A, Misao K, Omoto F, Yamagishi R, Tanaka K, Takada K, et al. A study of the association between sleep habits and problematic behaviors in preschool children. Chronobiol Int. 2008;25:549–64. doi: 10.1080/07420520802261705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Minde K, Popiel K, Leos N, Falkner S, Parker K, Handley-Derry M. The evaluation and treatment of sleep disturbances in young children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1993;34:521–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hiscock H, Canterford L, Ukomunne OC, Wake M. Adverse associations of sleep problems in Australian preschoolers: national population study. Pediatrics. 2007;119:86–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gregory AM, Van der Ende J, Willis TA, Verhulst FC. Parent-reported sleep problems during development and self-reported anxiety/depression, attention problems, and aggressive behavior later in life. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:330–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ben-Gashir MA, Seed PT, Hay RJ. Are quality of family life and disease severity related in childhood atopic dermatitis? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:455–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis-Jones MS. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:984–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hon KL, Leung TF, Wong KY, Chow CM, Chuh A, Ng PC. Does age or gender influence quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:705–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.02853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricci G, Bendandi B, Bellini F, Patrizi A, Masi M. Atopic dermatitis: quality of life of young Italian children and their families and correlation with severity score. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2007;18:245–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2006.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY, Dykes PJ. The Infant's Dermatitis Quality of Life Index. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:104–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.03960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis-Jones S. Quality of life and childhood atopic dermatitis: the misery of living with childhood eczema. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:984–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romanos M, Gerlach M, Warnke A, Schmitt J. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and atopic eczema modified by sleep disturbance in a large population-based sample. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:269–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.093534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitt J, Romanos M, Schmitt NM, al E. Atopic Eczema and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in a Population-Based Sample of Children and Adolescents. JAMA. 2009;301:724–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Camfferman D, Kennedy JD, Gold M, Martin AJ, Lushington K. Eczema and sleep and its relationship to daytime functioning in children. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14:359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schmitt J, Romanos M. Lack of studies investigating the association of childhood eczema, sleeping problems and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20:299–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2008.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ricci G, Patrizzi A, Baldi E, Menna G, Tabanalelli M, Masi M. Long term follow up of atopic dermatitis: retrospective analysis of related risk factors and association with concomitant allergic diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006:567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Syabbalo N. Chronobiology and chronopathophysiology of nocturnal asthma. Int J Clin Pract. 1997;51:455–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craig TJ, McCann JL, Gurevich F, Davies MJ. The correlation between allergic rhinitis and sleep disturbance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:S139–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borres MP. Allergic rhinitis: more than just a stuffy nose. Acta Paediatrica. 2009;98:1088–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagnano M, van Wijngaarden E, Connolly HV, Carno MA, Forbes-Jones E, Halterman JS. Sleep-disordered breathing and behaviors of inner-city children with asthma. Pediatrics. 2009;124:218–25. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hanifin JM. Basic and clinical aspects of atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy. 1984;52:386–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pink B. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) - Technical Paper. In: Statistics ABo, ed. Commonwealth of Australia; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landgraf JM, Abetz L, Ware JE. The CHQ user's manual. 1st ed. Boston, M.A.: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): Initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:942–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holm EA, Wulf HC, Stegmann, Jemec GBE. Life quality assessment among patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154:719–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.07050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC): rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:483–91. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, Romoli M, Innocenzi M, Cortesi F, et al. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC). Construction and validation of an instrument to evaluate sleep disturbances in childhood and adolescence. J Sleep Res. 1996;5:251–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1996.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Conners CK. Conner's Parent Rating Scale - Revised. Tonawanda, New York: Multi-Health Systems Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei JL, Mayo MS, Smith HJ, Reese M, Weatherly RA. Improved behaviour and sleep after adenotonsillectomy in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:974–9. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.10.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cortese S, Maffeis C, Konofal E, Lecendreux M, Comencini E, Angriman E, et al. Parent reports of sleep/alertness problems and ADHD symptoms in a sample of obese adolescents. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:587–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Constantin E, Kermack A, Nixon G, Tidmarsh L, Ducharme FM, Brouillete RT. Adenotonsillectomy improves sleep, breathing, quality of life but not behavior. J Pediatr. 2007;150:540–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arbuckle J. Amos 5.0 Computer software. Chicago, Ill: SPSS; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steiger JH. Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behav Res. 1990;25:173–80. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2502_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol Bull. 1990;107:238–46. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoyle RH. The structural equation modelling approach: Basic concepts and fundamental issues. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modelling: Concepts, issues and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacCallum RC, Browne M.W., Sugawara H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modelling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1:130–49. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kohler MJ, Lushington K, Kennedy JD. Neurocognitive performance and behaviour before and after treatment of sleep disordered breathing in children. Nat Sci Sleep. 2010;2:159–85. doi: 10.2147/NSS.S6934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elliot BE, Luker K. The experiences of mothers caring for a child with severe atopic eczema. J Clin Nurs. 1997;6:241–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Absolon CM, Cottrell D, Eldridge SM, Glover MT. Psychological disturbance in atopic eczema: the extent of the problem in school-aged children. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:241–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18121896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Montgomery-Downs HE, Jones VF, Molfese VJ, Gozal D. Snoring in preschoolers: associations with sleepiness, ethnicity, and learning. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2003;42:719–26. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.David TJ. The investigation and treatment of severe eczema in childhood. International Medicine Supplement. 1983;6:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. An audit of the impact of a consultation with a paediatric dermatology team on quality of life in infants with atopic eczema and their families: further validation of the Infants' Dermatitis Quality of Life Index and Dermatitis Family Impact score. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1249–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]