Abstract

α6β2β3* acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) on dopaminergic neurons are important targets for drugs to treat nicotine addiction and Parkinson's disease. However, it has not been possible to efficiently express functional α6β2β3* AChRs in oocytes or transfected cells. α6/α3 subunit chimeras permit expression of functional AChRs and reveal that parts of the α6 M1 transmembrane domain and large cytoplasmic domain impair assembly. Concatameric subunits permit assembly of functional α6β2β3* AChRs with defined subunit compositions and subunit orders. Assembly of accessory subunits is limiting in formation of mature AChRs. A single linker between the β3 accessory subunit and an α4 or α6 subunit is sufficient to permit assembly of complex β3-(α4β2)(α6β2) or β3-(α6β2)(α4β2) AChRs. Concatameric pentamers such as β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 have been functionally characterized. α6β2β3* AChRs are sensitive to activation by drugs used for smoking cessation therapy (nicotine, varenicline, and cytisine) and by sazetidine. All these are partial agonists. (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChRs are most sensitive to agonists. (α6β2)2β3 AChRs have the greatest Ca2+ permeability. (α4β2)(α6β2)β3 AChRs are most efficiently transported to the cell surface, whereas (α6β2)2β3 AChRs are the least efficiently transported. Dopaminergic neurons may have special chaperones for assembling accessory subunits with α6 subunits and for transporting (α6β2)2β3 AChRs to the cell surface. Concatameric pentamers and pentamers formed from combinations of trimers, dimers, and monomers exhibit similar properties, indicating that the linkers between subunits do not alter their functional properties. For the first time, these concatamers allow analysis of functional properties of α6β2β3* AChRs. These concatamers should enable selection of drugs specific for α6β2β3* AChRs.

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) that contain α6, β2, β3, and sometimes α4 subunits (α6β2β3* AChRs) are found in aminergic neurons, primarily in presynaptic locations (Champtiaux et al., 2002, 2003; Gotti et al., 2010). These AChRs are potentially important drug targets for antagonists in nicotine addiction. For example, knockout of α6β2β3* AChRs in dopaminergic neurons of the ventral tegmental area or blockage of their function in the endings of these neurons in the nucleus accumbens inhibits nicotine reward and self-administration of nicotine (Pons et al., 2008; Jackson et al., 2009; Brunzell et al., 2010). α6β2β3* AChRs are potentially important targets for agonists or positive allosteric modulators in Parkinson's disease, because they promote release of dopamine and mediate neuroprotection of the dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra that die in this disease (Quik and McIntosh, 2006).

Expression of homogenous populations of α6β2β3* AChRs is critical for selecting and characterizing drugs that interact with these subtypes but has proven very difficult. From studies of subunit knockouts, precipitation with subunit-specific antibodies, and blockage of α6* AChR function in synaptosomes with α conotoxin MII, it is inferred that dopaminergic endings express several AChR subtypes: (α6β2)2β3, (α6β2)(α4β2)β3, (α4β2)2β2, (α4β2)2α5, and (α4β2)2β3 (Gotti et al., 2007, 2010; Salminen et al., 2007). In rodents, α6β2β3* AChRs make up approximately 34% of the total, but in primates they comprise approximately 75% of the total (Quik and McIntosh, 2006; Gotti et al., 2010). α6β2β3* AChRs in synaptosomes are exceptionally sensitive to activation by nicotine (Salminen et al., 2007). α6β4* AChR function can be measured using Xenopus laevis oocytes (Gerzanich et al., 1997). However, in oocytes, α6 and β2 assemble very efficiently to form ACh binding sites, but mature pentamers are not formed; consequently, oligomers accumulate within the cells (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Human α6* AChRs have been expressed in permanently transfected human embryonic kidney cell lines, and their sensitivity to up-regulation by nicotine has been analyzed (Tumkosit et al., 2006). The amounts of AChRs expressed are too low for functional assays. As an alternative to expression of α6 in cell lines, functional effects have been inferred by expressing in transgenic mice fluorophore labeled α6 or α6 mutants with hyperactive gating properties (Drenan et al., 2008a,b). Chimeras with the extracellular domain of human α6 and the remainder of α3 or α4 subunits form functional AChRs in X. laevis oocytes, proving that association of α6 subunit extracellular domains is not a barrier to assembly (Kuryatov et al., 2000). It seems likely that efficient α6β2β3* AChR assembly requires as-yet-unknown chaperones unique to aminergic neurons.

Expression of linked subunits to form concatameric AChRs provides a method for overcoming the need for specific chaperones to express AChR subtypes of specific subunit compositions and orders. The use of (AGS)n linkers between α4 and β2 subunits provides stable concatamers when expressed in oocytes (Zhou et al., 2003). A linked pair of α4 and β2 expressed with excess monomeric subunits can form uniform populations of AChR subtypes whose agonist sensitivities and Ca2+ permeabilities can be assayed [e.g., (α4β2)2β2, (α4β2)2α4, (α4β2)2α5, and (α4β2)2β3 (Zhou et al., 2003; Tapia et al., 2007)]. Pentameric concatameric α4β2 AChRs have been expressed (Carbone et al., 2009). Pentameric concatamers are especially important when expressing complex (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChR subtypes, because a mixture of these subunits will express a mixture of subtypes. Furthermore, because of the efficiency with which α4 and β2 assemble with each other, and the very high efficiency with which the β3 accessory subunit assembles with them, (α4β2)2β3 AChRs preferentially assemble (Kuryatov et al., 2008).

Here we use human AChR subunits expressed in X. laevis oocytes to investigate assembly of functional α6β2β3* AChRs. α6/α3 chimeras are used to discover that barriers to assembly of α6β2β3* AChRs arise from two amino acids in a putative endoplasmic reticulum retention sequence in the α6 M1 transmembrane region as well as from unknown sequences within the α6 large cytoplasmic domain. Concatamers with 1 to 4 linkers are used to express α6β2β3* AChR subtypes and to determine their sensitivities to activation and their permeabilities to Ca2+. Concatamers overcome the need for special chaperones to assemble α6β2β3* AChRs. These studies suggest that assembly of the accessory subunit is a rate-limiting step in forming mature pentamers. A special chaperone may be required to efficiently transport (α6β2)2β3 AChRs to the cell surface. The presence of a single α4 subunit in (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChRs ensures efficient transport to the surface. These concatameric α6β2β3* AChRs will be useful for assaying the effects of existing drugs and for selecting new α6β2β3* AChR-selective drugs.

Materials and Methods

α6/α3 Chimeras.

We have made chimeras from α6 and α3 subunits (Kuryatov et al., 2000). To splice together the cytoplasmic domain of α6 cDNA with the corresponding part of α3 cDNAs, we introduced an ApaLI restriction site at position Ile 297 of α6 cDNA using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The construct was then sequenced to verify that only the desired mutation was present. This restriction site is present in native α3 cDNA. Using this restriction site and XbaI, we replaced the cytoplasmic domain of α3 with the α6 domain in the α3 subunit and the cytoplasmic domain of α6 with the α3 domain in the α6 subunit. To make chimeras in which only transmembrane regions 1 to 3 were from another subunit, we started with the chimera α3/α6 in which the extracellular domain was from α3 and the remainder from α6 or the chimera α6/α3 as described previously (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Then the cytoplasmic domains were switched as described above.

α6 and α3 have identical M2 transmembrane domains. To replace the M1 or M3 domain in the α3 subunit with α6 sequence, we introduced a BstEII restriction site in the α6 subunit at position Lys 241. Using a BspEI restriction site at position Arg 207 and a BstEII site at position Lys 241, we replaced the M1 domain of α3 with the α6 domain. Using restriction sites BstEII at position Lys 241 and ApaLI at position Ile 297, we replaced the M3 domain of α3 with the α6 domain.

To identify the most important amino acid residue responsible for functional expression in α6/α3 chimeras, we mutated Leu 211 to Met and Leu 223 to Phe in α3 subunit using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis kit.

Concatamer Construction.

α4(AGS)6β2, α4(AGS)12β2, and β2(AGS)6α4 dimeric concatamers were prepared as described in Zhou et al. (2003). DNA was purified from gel slices using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). All restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Ipswich, MA), and all digestions were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ligations were performed with T4 DNA ligase and ligation buffer (New England Biolabs). Mutagenesis PCR was performed using the QuikChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit. The thermocycler was programmed as described in the kit protocol.

First, dimeric concatamers were constructed. To introduce the β3 sequence in front of α4 we used the (AGS)6α4 and (AGS)12α4 plasmids prepared previously in our lab (Zhou et al., 2003). At the end of the coding sequence of β3, we introduced a BspEI restriction site. (AGS)6α4 and (AGS)12α4 plasmids were digested with XmaI, HinDIII, and BstEII. The mutated β3 was digested with HinDIII and BspEI. HinDIII-BspEI fragment from β3 and HinDIII-BstEII fragments from (AGS)6α4 and (AGS)12α4 plasmids were ligated to produce β3(AGS)6α4 and β3(AGS)12α4 plasmids. To construct the β3(AGS)6α6 concatamer, an FspI restriction site was introduced at the beginning of the coding sequence of α6 and at the beginning coding sequence of α4 from the β3(AGS)6α4 concatamer constructed previously. Mutated α6 was digested with SacI and FspI, and mutated β3(AGS)6α4 was digested with FspI and HinDIII to cut out the β3 subunit. Digested α6 and β3 were ligated into pSP64 digested with HinDIII and SacI. α6(AGS)6β2 was constructed by mutating α6 to insert a KpnI restriction site at the end of coding sequence of the subunit. This mutated α6 subunit was digested with KpnI and SacI and ligated with (AGS)6β2 pSP64 digested with KpnI and SacI. α6(AGS)12β2 concatamer was prepared by replacing (AGS)6 linker with (AGS)12 from α4(AGS)12β2 concatamer. In the β3(AGS)6α6 concatamer, we introduced an AgeI restriction site at the beginning of coding sequence of α6. Using KpnI and AgeI sites, the (AGS)12 linker was inserted between β3 and α6.

Next, trimeric concatamers were constructed. To construct β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)6β2, a KpnI restriction site was introduced at the end of the coding sequence of α6 in the previously prepared β3(AGS)6α6 concatamer. This vector was then digested with KpnI and SacI. An (AGS)6β2 fragment was obtained by digestion of the α6(AGS)6β2 concatamer with KpnI and SacI restriction enzymes. Ligation of these two fragments produced β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)6β2. To obtain β3(AGS)6 α6(AGS)12β2 and β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 trimers, we used the EcoRV restriction site from the α6 sequence and the PvuI restriction site from the pSP64 plasmid. β3(AGS)6α6, β3(AGS)12α6 and α6(AGS)12β2 were digested with these two restriction enzymes, then were ligated together to produce β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 and β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 trimers. β3(AGS)6α4, β3(AGS)12α4 and α4(AGS)12β2 were digested with PvuI and NsiI restriction enzymes and their fragments were ligated together to produce β3(AGS)6α4(AGS)12β2 and β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2 trimers.

Finally, pentameric concatamers were constructed. The stop codon at the end of β2 in the β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 trimer was replaced with a BspEI restriction site. Another mutant was prepared with the BspEI site at the end of the coding sequence of β3 in the β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 trimer that replaces the KpnI restriction site. Then the β3 sequence in the β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 trimer was replaced with β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 trimer using XbaI and BspEI restriction sites. This resulted in the β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 pentamer. We introduced the same BspEI site at the end of the coding sequence of β3 in the β3(AGS)6α4(AGS)12β2 concatamer. Using the same restrictions sites, XbaI and BspEI, we ligated the XbaI-BspEI β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 fragment to form the β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α4(AGS)12β2 pentamer. The end of β2 coding sequence in the β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2 trimer was replaced with the BspEI restriction site, and the XbaI-BspEI β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2fragment was ligated with the (AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 XbaI-BspEI fragment from the β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 trimer with the BspEI restriction site at the end of the β3 coding sequence.

DNA Preparation.

Two microliters of ligations were transformed into XL-10 Gold Ultracompetent cells (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using the protocol included in the kit. Transformant (100 μl) was plated onto LB-ampicillin agar plates after overnight incubation at 37°C. 6 to 8 colonies were used to inoculate the same number of culture tubes containing 2.5 ml of LB with 100 μg/ml ampicillin. These cultures were subsequently used in the QIAquick Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Miniprep DNA was tested for correct sequence by restriction enzyme digestion and subsequent agarose gel electrophoresis. The miniprep culture with correct DNA was used to make a streak plate. A colony from this streak plate was used to inoculate 100 ml of LB with the same concentration of ampicillin as described above. This culture was subsequently used to purify DNA with the Qiagen Plasmid Midiprep Kit (QIAGEN). DNA concentration was calculated by spectrophotometry.

Oocyte Injection.

cRNA from 1 μg of linearized cDNA templates of subunits, chimeras, or concatamers in the pSP64 vector was synthesized using SP6 RNA polymerase from the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). X. laevis oocytes were injected cytosolically with 20 to 95 ng of RNA per oocyte and incubated for 4 to 7 days in media made up of 50% L-15 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA), 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 units/ml penicillin, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin at 18°C. Media were changed as needed. cRNAs for the β3(AGS)6α4 + β2 + α6 combination was injected at a ratio of 4:2:1. cRNAs for the β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)6β2 + α4(AGS)6β2, β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 + α4(AGS)6β2 combinations were injected at various ratios favoring the formation of β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)6β2 and β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2. The concatamer combinations β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 + α6(AGS)12β2 and β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2 + α6(AGS)12β2 combination were injected in equal ratios. cRNAs β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 and β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α4(AGS)12β2 (20 ng) and β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 (95 ng) were injected in oocytes. α31–297α6 + β2, α31–207α6 + β3(AGS)12α6 + β2, α31–207α6208–241α3 + β2, α31–241α6242–297α3 + β2, M211Lα3 + β2, L223Fα3 + β2 combination cRNAs were injected at equal ratios totaling 50 ng/oocyte.

Surface Expression of AChRs.

Surface expression was determined by incubating oocytes in ND-96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM ΜgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5) that contained 10% heat-inactivated normal horse serum and 5 nM β2-specific 125I-mAb 295 (Whiting and Lindstrom, 1988) for 3 h at room temperature, followed by three wash steps with ice-cold ND-96 solution (96 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) to remove nonspecifically bound mAbs. Nonspecific binding was determined by incubating noninjected oocytes under similar conditions.

Sucrose Gradient Sedimentation.

Triton X-100-solubilized AChRs from oocytes were prepared as described by Kuryatov et al. (2000). Groups of 30 oocytes were homogenized by repeated pipetting in 1 ml of buffer A (50 mM Na2HPO4, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 5 mM benzamidine, 15 mM iodoacetamide, and 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). Cell membranes and particulates were pelleted by centrifuging at 15,000g for 15 min. Membrane proteins were resuspended by pipetting and solubilized in 150 μl of buffer A containing 2% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. Debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000g for 15 min. Aliquots (150 μl) of the lysates, mixed with 2 μl of 1 μg/ml pure extract of Torpedo californica electric organ, were loaded onto 11.3 ml of sucrose gradients [linear 5−20% sucrose (w/w) in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, that contained 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM NaN3, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100]. The gradients were centrifuged for 16 h at 40,000 rpm in a rotor (SW-41; Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) at 4°C. The fractions were collected at 15 drops per well from the bottom of the tubes and used for additional analysis. Fifty microliters of each fraction were transferred to mAb 295-coated wells to isolate β2 AChRs for measurement of [3H]epibatidine binding, and 20 μl of each fraction were transferred to mAb 210-coated wells to isolate α1-containing T. californica AChRs used as molecular weight standards. Fractions in mAb 295-coated wells were incubated with 2 nM [3H]epibatidine at 4°C overnight. Fractions in mAb 210-coated wells were incubated with 1 nM 125I-α-bungarotoxin at 4°C overnight. Afterward, the wells were washed three times with PBS and 0.5% Triton X-100; bound [3H]epibatidine was determined by liquid scintillation counting, whereas the bound 125I-α-bungarotoxin was determined by gamma counting.

Sucrose Gradient Sedimentation of Surface AChRs.

Oocytes were first washed three times with PBS (100 mM NaCl and 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) buffer and then incubated in PBS buffer that contained 0.5 μg/ml EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin [sulfosuccinimidyl 2-(biotinamido)-ethyl-1,3-dithiopropionate] (Pierce, Rockford, IL) at room temperature for 30 min to label the surface proteins. After incubation, oocytes were gently washed three times in PBS buffer. Triton X-100-solubilized AChRs from oocytes were prepared as described previously. A sucrose gradient was run following the protocol described above. Streptavidin plates (Greiner Bio-One North America Inc., Monroe, NC) were used for isolation of biotin-labeled AChRs. After centrifugation, 15-drop fractions were collected, and then 20 μl of each fraction were transferred to mAb 210-coated wells to determine the T. californica AChR profile, 50 μl were transferred to mAb 295-coated plates, and 95 μl of each fraction were transferred to streptavidin-coated wells. Fractions in mAb 295-coated wells and streptavidin-coated wells were incubated with 2 nM [3H]epibatidine at 4°C overnight to measure the amount of epibatidine-binding sites for total and surface AChRs. Fractions in mAb 210-coated wells were incubated with 1 nM 125I-α-bungarotoxin at 4°C overnight to determine binding to T. californica.

Western Blotting.

AChRs solubilized as described above were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Electrophoresis was performed on precast 4-to-15% gradient acrylamide gels containing SDS (Novex, San Diego, CA). The transfers were conducted using a semidry electroblotting chamber Semi-Phor (Hoefer Scientific Instruments, San Francisco, CA) to Trans-Blot Medium polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The blots were quenched after transfer with 5% Carnation dried nonfat milk for 1 h in 0.5% Triton X-100, PBS, and 10 mM NaN3. Blots were probed with rat antiserum to β2 (diluted 1:500) and mAb 349 to α6 (1:1000) (Tumkosit et al., 2006) and then incubated with 2 nM 125I-labeled goat anti-rat IgG for 3 h at room temperature. After washing in 0.5% Triton with NaN3, blots were visualized by autoradiography.

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell membrane currents were recorded 4 to 7 days after injection of oocytes with various RNA combinations using a two-microelectrode voltage-clamp amplifier (Oocyte Clamp OC-725; Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT). Currents were measured in response to the application of various concentrations of agonists, including ACh and nicotine, as well as inhibitors, including methyllycaconitine and α-conotoxin MII. Recordings were analyzed using MacLab software (ADInstruments, Castle Hill, NSW, Australia). To obtain agonist dose/response curves, increasing concentrations of ACh agonists were applied at 3-min intervals. The recording chamber was constantly washed with ND-96 containing 0.5 μM atropine (to block muscarinic AChR responses sometimes found in the oocytes). At this concentration, atropine reduced the response to 1 μM ACh by 7% in the case of β3-α4-β2-α6-β2, 10% in the case of β3-α6-β2-α6-β2, and 15% in the case of β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 concatamers. These small effects of atropine were not altered by changing the voltage from −50 to −100 mV; thus, they were probably not due to channel block. We compare our results with those of studies on synaptosomes that were performed in 1 μM atropine (Salminen et al., 2004, 2007); thus, the similarities between the EC50 values we observe and those for α6* AChR subtypes inferred from synaptosomes studies reflect measurements under comparable conditions. Recordings were performed at a clamp potential of −50 mV, except β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 cRNAs that were recorded at −70 mV to amplify the responses. The mean value of at least four oocytes per combination was taken to graph dose/response curves. Values are expressed ± S.E.

Ca2+ permeability of pentameric concatamers was assayed by comparing currents obtained in response to 30 μM ACh in modified ND96 and in an extracellular solution containing Ca2+ as the only cation (Tapia et al., 2007). In both cases Cl−-free solutions were used to avoid effects of oocyte Cl− channels. The modified ND96 was made with 90 mM NaOH, 2.5 mM KOH, 1.8 mM Ca(OH)2, and 10 mM HEPES buffered to pH 7.3 with methanesulfonic acid. The Ca2+-only solution contained 1.8 mM Ca(OH)2 titrated to pH 7.5 with HEPES and 178 mM dextrose to maintain osmolarity. Intracellular electrodes were filled with 2.5 M potassium methanesulfonate.

Results

Problems with Expressing α6β2* AChRs from Free Subunits in X. laevis Oocytes.

Expression of α6β4 or α6β4β3 subunit combinations in X. laevis oocytes produced functional AChRs, but α6β2 or α6β2β3 combinations did not (Gerzanich et al., 1997; Kuryatov et al., 2000). The α6β2α5 combination produced modest amounts of rapidly desensitizing AChRs (Kuryatov et al., 2000). This suggests that the accessory subunit is important. β3 and α5 can function only as accessory subunits, whereas α6, α4, β2 … can both participate in forming ACh binding sites and function as the fifth “accessory” subunit that does not participate in forming an ACh binding site (Kuryatov et al., 2008). All agonists tested were partial agonists relative to ACh. This suggests that α6* AChR binding sites may intrinsically result in partial activity for many agonists. α6 subunits in combination with β2, β2 + β3, or β2 + α5 subunits were much more effective at forming ACh binding sites labeled by [3H]epibatidine than were α3 + β2, α4 + β2, α3 + β4, α6 + β4, or α6 + β4 + β3 combinations (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Despite partially assembling to form large numbers of ACh binding sites, far fewer α6β2 AChRs than α3β2 AChRs could be labeled on oocyte surfaces with 125I-mAb 295 directed at β2 subunits (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Whereas α3β2 AChRs assembled into mature pentamers that sedimented on sucrose velocity gradients at the expected size, intermediate between monomers and dimers of T. californica AChR, α6β2 assembled into amorphous complexes larger than dimers (Kuryatov et al., 2000).

Coexpression of α6, α3, and β2 subunits results in assembly of functional AChRs, most likely (α6β2)(α3β2)β2, as indicated by full efficacy of nicotine on this combination but only partial efficacy on (α3β2)2β2 (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Partial efficacy on α3β2 AChRs results from channel block by nicotine as a result of interaction with the α3 M2 channel-lining residue V 258 when two α3 subunits are present in the AChR (Rush et al., 2002). Robust function of the (α6β2)(α3β2)β2 subtype suggests that complex α6* AChR subtypes containing a single (α6β2) ACh binding site can efficiently assemble and be transported to the cell surface. Coexpression of the α6 + α4 + β2 combination resulted in limited coassembly of α6α4β2 AChRs, as indicated by subunit-specific immune precipitation. However, there was no obvious difference from α4β2 AChRs in terms of functional properties (Kuryatov et al., 2000). It is not clear whether coassembled AChRs functioned on the cell surface.

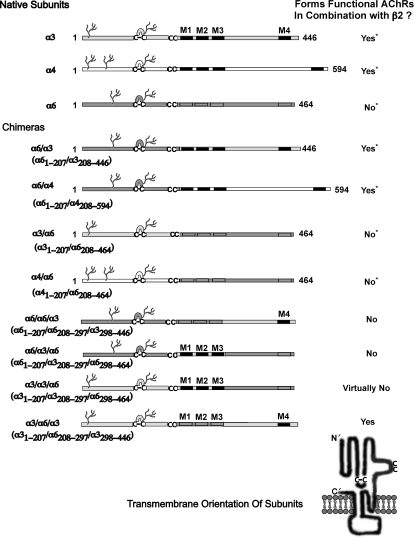

Chimeras of α6 subunits with α3 or α4 have helped to reveal parts of the sequence of α6 that influence its assembly with β2 subunits (Fig. 1). Chimeras of the extracellular domain of α6 (1–207) with the remainder of α3 (208–446) or α4 (208–594) produced functional AChRs when expressed with β2 subunits (Kuryatov et al., 2000). This indicates that the extracellular domain of α6 efficiently assembles with that of β2 to form ACh binding sites and pentameric AChRs. Sensitivities of these chimeras to nicotine were rather low (EC50 = 4.2 ± 0.9 μM, n = 3 for α6/α3β2; EC50 = 3.2 ± 0.5 μM, n = 3 for α6/α4β2). All α6/* chimeras, whether in combination with β2 or with β4, were very sensitive to blockage by α conotoxin MII. This indicates that α6 contributes elements to the ACh binding site, which confers sensitivity to this toxin. α Conotoxin MII is selective only for α6β2* AChRs and for α3β2 AChRs (Dowell et al., 2003). Chimeras with the extracellular domain of α3 or α4 and the remainder of α6 were not functional. This indicates that transmembrane and/or cytoplasmic domain regions of α6 impair formation of pentameric AChRs.

Fig. 1.

Design of α6 chimeras. This is an expanded form of a figure from Kuryatov et al. (2000). An asterisk indicates data from that article. The remaining chimeras depicted are unique to the current article. The branched structures depict glycosylation. The linked Cs depict the cysteine loop characteristic of all subunits of this gene family and the disulfide linked pair of successive cysteines characteristic of the C-loop of α subunits that closes over the ACh binding site when agonists are bound. The four transmembrane domains are designated M1 to M4. In the diagrammatic representation of the transmembrane orientation of a subunit polypeptide chain, the N terminus at the extracellular apex is indicated by N′, and the C terminus at the end of the short extracellular sequence after M4 is marked C′.

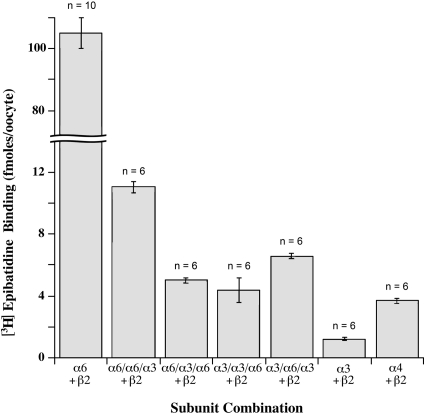

The transmembrane and cytoplasmic sequences of α6 that impair assembly of functional AChRs were identified by studies of chimeras between α6 and α3 subunits. α6 subunits are most closely related in sequence to α3. A chimera in which the cytoplasmic domain and M4 of α6 was replaced by that of α3 assembled with β2 to form ACh binding sites (Fig. 2). Only 10% as many binding sites were formed as with wild-type α6. Thus, regions C-terminal of M3 are important for the exceptionally efficient assembly of α6 with β2. Replacement of the transmembrane domains M1 to M3 of α6 with those of α3 reduced by 95% the amount of ACh binding sites produced in combination with β2 (Fig. 2). Thus, sequences within these transmembrane regions are also important for the exceptionally efficient assembly of α6 with β2. Replacement of the large cytoplasmic domain through the C terminus of α3 with α6 produced 3.7 fold more than wild-type α3 epibatidine binding sites (Fig. 2). Thus, the α6 regions that are important in its ability to assemble with β2 could confer increased assembly on α3. Replacing the transmembrane domains M1 to M3 of α3 with those of α6 produced more ACh binding sites than did wild-type α3 in combination with β2 (Fig. 2). Thus, the transmembrane regions that were important to the assembly of α6 with β2 could also confer increased assembly on α3. Replacing the cytoplasmic domain and M4 of α3 with that of α6 resulted in assembly of some AChRs of the size expected of mature α3β2 AChRs but also in the assembly of a variety of larger aggregates (Fig. 3). Thus, the α6 sequence confers assembly with β2 to form subunit pairs with ACh binding sites, and these assemble into larger aggregates, but not efficiently into pentameric AChRs.

Fig. 2.

Formation of ACh binding sites labeled with [3H]epibatidine by expression in oocytes of AChR combinations of wild-type and chimeric subunits. Chimeric subunits are written in three segments to indicate extracellular domain/M1–M3 transmembrane domains/large cytoplasmic domain, M4, C terminus. ACh binding sites are formed at the interface between the extracellular domains of the + side of α subunits and the − side of β subunits (Gotti et al., 2007). AChRs were solubilized from oocytes using Triton X-100, isolated using mAb 295 to β2 subunits coated on microwells, then labeled with [3H]epibatidine. Expression of free α6 and β2 subunits resulted in formation of large amounts of ACh binding sites with high affinity for epibatidine that could be isolated from Triton X-100 extracts by a mAb to the extracellular domain of β2 subunits that binds well only when β2 is associated with α subunits. This result confirms our observation that free α6 and β2 subunits expressed in oocytes assemble exceptionally efficiently to form ACh binding sites at their interface (Kuryatov et al., 2000). The amount of epibatidine binding sites formed by the combination of α6 with β2 was more than 25-fold the amounts formed with either α3 or α4 in combination with β2. In a mature α6β2* AChR there should be two α6β2 pairs and an accessory subunit, either β2, β3, or α6. However, free α6 and β2 subunits in oocytes do not form mature pentameric AChRs, instead they form amorphous large aggregates (Kuryatov et al., 2000). A chimeric α6 subunit in which the large cytoplasmic domain through the C terminus of α6 was replaced with that of α3 formed far fewer epibatidine binding sites when expressed with β2 subunits. This shows that the cytoplasmic domain or more C-terminal sequences of α6 contribute to efficient assembly with β2. A chimeric α6 subunit in which transmembrane domains 1 to 3 were replaced with those of α3 formed even fewer epibatidine binding sites when expressed with β2. This shows that sequences within these transmembrane domains contribute to efficient assembly with β2 subunits. The converse experiment of replacing the large cytoplasmic domain through the C terminus of α3 with that of α6 resulted in the formation of a relatively small amount of epibatidine binding sites, though more than three times the number of binding sites formed by wild type α3 in combination with β2. An α3 chimera with transmembrane domains 1 to 3 of α6 formed somewhat more epibatidine binding sites in combination with β2. Thus, α6 transmembrane and cytoplasmic sequences contribute to efficient assembly with β2 and can enhance the assembly of α3 with β2 when part of chimeras with α3.

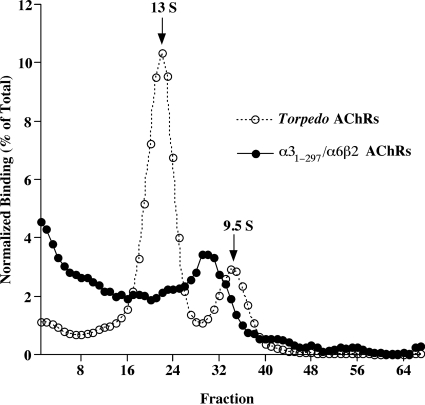

Fig. 3.

A chimera in which an amino acid sequence C-terminal of M3 of α3 (including the large cytoplasmic domain and M4) was replaced with that of α6 formed AChRs in combination with β2 of the size expected of mature α5/α6β2 AChRs but also a greater amount of larger aggregates. Sucrose gradient sedimentation velocity analysis revealed a component of the size expected of mature pentamers, which sedimented between T. californica AChR monomers and dimers, as well as greater amounts of larger aggregates. α3β2 AChRs sediment only as mature pentamers, whereas α6β2 sediments only as aggregates (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Thus, the presence of some mature AChRs reflects the effects of α3 sequences in the chimera, whereas the presence of aggregates reflects the effects of α6 sequences in the chimera. Chimeras were isolated on microwells coated with mAb 295 to β2 subunits, then labeled with [3H]epibatidine. Aliquots of the same fractions were incubated in microwells coated with mAb 210 to α1 subunits to isolate T. californica AChR monomers and dimers that were included as internal standards. These were labeled with 125I-α-bungarotoxin.

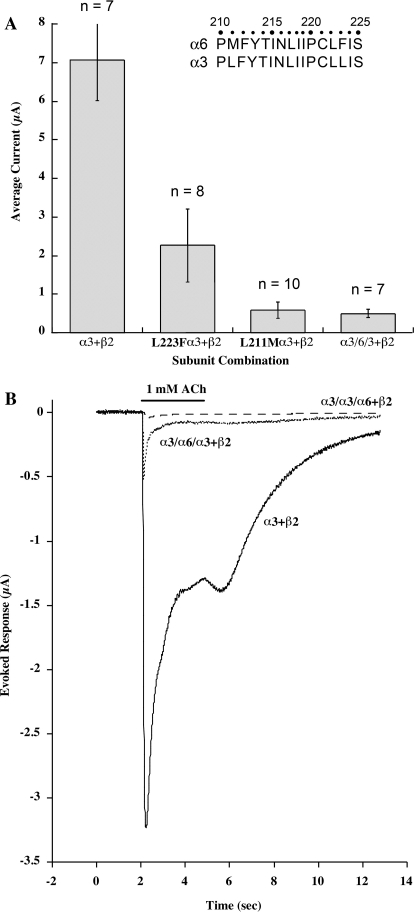

Changing only α3 M1 transmembrane domain Leu 223 to Phe, as in α6, reduced ACh-induced current by 67% (Fig. 4). Substituting α3 Leu 211 with the Met of α6 had an even greater effect, reducing current by 92%. This single amino acid change reduced current virtually as much as did replacing transmembrane domains M1 to M3 of α3 with those of α6. The sequence at the beginning of the α1 M1 sequence corresponding to 210 to 217 is an endoplasmic reticulum retention sequence (Wang et al., 2002). This sequence is conserved in many subunits, but the unusual Met 211 in α6 may disrupt it. This sequence is thought to be important for retaining subunits in the endoplasmic reticulum while they are being assembled and is covered up as AChR pentamers complete assembly, permitting transport through the Golgi apparatus to the surface membrane. The change of α3 Leu 211 to Met, which is found in α6 at that position, may impair assembly of mature AChRs.

Fig. 4.

α3 subunit chimeras containing α6 M1 amino acids are impaired from assembling functional AChRs in combination with β2 subunits. Sequences within the M1 transmembrane domain of α3 and α6 subunits are compared in an inset to A. A, amplitudes of currents of α3β2 AChRs produced in response to 1 mM ACh are reduced when α3 chimeras containing single α6 amino acids or transmembrane domains of α6 are used. Oocytes injected with equal amounts of mRNAs for α3 and β2 subunits form enough AChRs to produce substantial currents. Replacement of α3 Leu 223 with the Phe of α6 greatly reduces these currents. Replacement of α3 Leu 211 with the Met of α6 has an even greater effect, approximately equivalent to that of an α3 chimera containing transmembrane domains M1 to M3 of α6. B, kinetics of the responses of α3β2 AChRs produced in response to 1 mM ACh are altered in chimeras of α3 with α6. Wild-type α3β2 AChRs produce large currents in response to this saturating concentration, which over 2 s are reduced by half through desensitization and channel block. An α3/α6/α3 chimera in which transmembrane domains 1 to 3 are replaced with those of α6 results in a low amplitude response that desensitizes almost completely in 1 s. An α3/α3/α6 chimera in which the cytoplasmic domain and other parts of α3 C-terminal of M3 are replaced by α6 results in virtually no functional AChRs. The loss of amplitude of chimeric responses reflects primarily failure to assemble mature AChRs. The more rapid and complete desensitization of the α3/α6/α3 chimera reflects effects of the presence of α6 M1 to M3 transmembrane domains in functional chimeric AChRs.

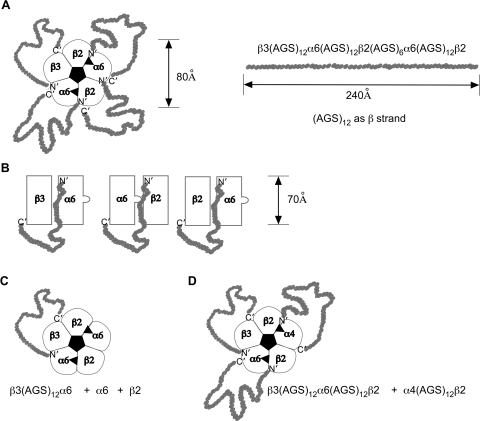

Concatamers Permit Assembly of Complex α6* AChR Subtypes.

Table 1 shows the linkers used to form concatamers. Figure 5 diagrammatically represents the arrangement of subunits in α6* AChRs and indicates how they are linked in concatamers. Table 2 lists the concatamers for which EC50 values are reported, showing some of these EC50 values, and shows the explicit and abbreviated nomenclature used to designate each of these concatamers. Linkers of 6 or 12 alanine, glycine, serine (AGS) sequences were used to link the C terminus of one subunit to the N terminus of the next. Because β2 subunits have a long C terminus (23 amino acids), only (AGS)6 was used to link their C termini to other subunits. All other shorter C-termini (e.g., α4 with eight amino acids) were linked using an (AGS)12 linker. This approach produced ACh subtypes with consistent pharmacological properties, whether they were formed of concatameric pentamers or mixtures of shorter concatamers plus free subunits. In studying linked pairs of α4 and β2 subunits, we previously discovered that short linkers can constrain the ability to assemble, prevent formation of an ACh binding site between the subunit pair, and reduce sensitivity to activation (Zhou et al., 2003). Here we found that using (AGS)6 instead of (AGS)12 after α6, α4, or β3 greatly reduced sensitivity to activation, as shown in the last entry in Table 2.

TABLE 1.

Linkers between Subunits

Added amino acids are shown in bold.

| Concatamer Pair | Sequence of Linkers and Adjacent Subunits | Linker Length |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acids (C′-tail + Linker + Amino Acids Added in Restriction Sites) | If Linker Were Extended Random Coil | ||

| Å | |||

| β2(AGS)6α4 | SAPSSKEG(AGS)6RAHA | 23 + 18 + 2 = 43 | 258 |

| α4(AGS)6β2 | WLAGMIQEGT(AGS)6TGTEER | 8 + 18 + 6 = 32 | 192 |

| α4(AGS)12β2 | WLAGMIQEGT(AGS)12TGTEER | 8 + 36 + 6 = 50 | 300 |

| β3(AGS)6α4 | WLHSYHSR(AGS)6RAHA | 11 + 18 + 2 = 31 | 186 |

| β3(AGS)12α4 | WLHSYHGT(AGS)12RAHA | 11 + 36 + 2 = 49 | 294 |

| β3(AGS)6α6 | WLHSYHGT(AGS)6TGCATE | 11 + 18 + 4 = 33 | 198 |

| β3(AGS)12α6 | WLHSYHGT(AGS)12CATE | 11 + 36 + 2 = 49 | 294 |

| α6(AGS)6β2 | GNTGKSGT(AGS)6TGTEER | 10 + 18 + 4 = 32 | 192 |

| α6(AGS)12β2 | GNTGKSGT(AGS)12TGTEER | 10 + 36 + 4 = 50 | 300 |

Fig. 5.

Diagrammatic representation of AChR subunit arrangements, and concatamer linkers. A, top view of a β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 concatameric pentamer. Its dimensions and subunit order are modeled after those of (α1γ)(α1δ)β1 AChRs (Unwin, 2005). The fully written out nomenclature for this construct linked from the C terminus of the first subunit to the N terminus of the next with a total of four linkers is shown. The length of an (AGS)12 linker is represented as if it were a β strand. This sequence of 36 amino acids should form a random coil much longer than minimally necessary to link the two subunits. A shorter linker of (AGS)6 allows assembly of β2(AGS)6α4 without constraining function because of the long 23-amino acid C-terminal domain of β2, but α4(AGS)6β2 is more constrained because α4 has a C-terminal domain of only eight amino acids (Zhou et al., 2003). B, side-view representations of linked subunit pairs. The bulge in the α subunit represents the C-loop of this subunit, which closes over the ACh binding site at the α/β2 interface when it is occupied by an agonist. C, top view of the same subtype as in A formed using a single β3-α6 concatamer pair in combination with free α6 and β2 subunits. D, top view of the (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 subtype formed from a concatameric β3-α6-β2 trimer and a concatameric α4-β2 dimer.

TABLE 2.

α6* AChR concatamers, both pentameric and mixtures of free and linked subunits

| AChR Subtype | Constructs (abbreviation) | EC50 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| ACh | Nicotine | ||

| μM | |||

| (α6β2)2β3 | β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 | 1.21 ± 0.09 | 0.387 ± 0.051 |

| β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 | n = 6 | n = 5 | |

| β3(AGS)12α6 + α6 + β2 | Expression level too low for accurate EC50 determination | ||

| β3-α6 +α6 + β2 | |||

| (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 | β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α4(AGS)12β2 | 0.828 ± 0.047 | 0.170 ± 0.079 |

| β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 | n = 5 | n = 4 | |

| β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 + α4(AGS)12β2 | 0.458 ± 0.046 | 0.306 ± 0.042 | |

| β3-α6-β2 + α4-β2 | n = 4 | n = 5 | |

| (α4β2)(α6β2)β3 | β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2(AGS)6α6(AGS)12β2 | 1.76 ± 0.25 | 0.397 ± 0.122 |

| β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 | n = 5 | n = 4 | |

| β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2 + α6 + β2 | 1.11 ± 0.09 | 0.397 ± 0.070 | |

| β3-α4-β2 + α6 + β2 | n = 4 | n = 7 | |

| β3(AGS)12α4 + α6 + β2 | 1.69 ± 0.14 | 0.584 ± 0.149 | |

| β3-α4 + α6 + β2 | n = 6 | n = 8 | |

| (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 | β3(AGS)6α6(AGS)6β2 + α4(AGS)6β2 | 113 ± 23 | 18.0 ± 4.6 |

| These concatamers with short linkers are not used elsewhere in this paper | n = 6 | n = 4 | |

The linear order in which AChR subunits are linked C terminus to N terminus does not necessarily reflect the order in which the subunits assemble in the mature AChR. The linker joins the short extracellular sequence that follows the fourth transmembrane domain α helix at the C terminus of one subunit to the N-terminal α helix at the extracellular tip of the next subunit. We showed that the concatameric pair β2(AGS)6α4 assembles preferentially in the order α4β2 to form an ACh binding site at their interface (Zhou et al., 2003). The linker of 43 amino acids of β2 C-terminal amino acids and (AGS)6 does not interfere with AChR function. These pairs assemble efficiently with β2, α4, β3, or α5 accessory subunits to form (α4β2)2X AChRs with the expected properties (where X indicates various accessory subunits) (Zhou et al., 2003; Tapia et al., 2007). β2 seems to assemble very avidly with α4 to form ACh binding site pairs or tetramers but seems inefficient at assembling in the accessory position. This may account for the pools of high-affinity assembly intermediates on which nicotine and other cholinergic ligands can act as pharmacological chaperones to promote assembly of mature AChRs (Kuryatov et al., 2005). β3 and α5 are avid at assembling in the accessory position in (α4β2)2X AChRs (Kuryatov et al., 2008). β4 also avidly assembles in the accessory position, perhaps accounting for the efficient assembly of (α3β4)2β4 AChRs and lack of pharmacological chaperone effect of nicotine on this subtype (Wang et al., 1998; Sallette et al., 2004). The 43-amino acid C terminus of β2 and linker in the concatameric pair β2(AGS)6α4 is quite flexible, allowing the β2 to serve as an accessory subunit of one pentamer and the α4 as an accessory subunit in another pentamer joined by the linker (Zhou et al., 2003). The 50-amino acid C terminus of α4 and linker in the α4(AGS)12β2 pair usually assembles to form ACh binding sites with other subunits (Zhou et al., 2003). This linker also can join two pentamers. Both β3(AGS)12α4 and β3(AGS)12α6 pairs can form AChRs in combination with free α6 and β2 subunits. Because β3 can function only in the accessory position, the linker must allow assembly in the order β3α4 or β3α6, leaving the α subunit free to form an ACh binding site with a free β2 subunit. The shorter β3(AGS)6α6 linker does not work in this experiment (data not shown), perhaps because it constrains β3 to assemble with the wrong side of α6. The longer β3(AGS)12α6 linker probably facilitates assembly of β3 in the accessory position. When only free α6 and β2 are expressed, many ACh binding sites are formed, but pentameric AChRs are not. Thus, β2 appears even less able to assemble in the accessory position with α6 than it is with α4. A mixture of free α6, β2, and β3 is very inefficient at assembling AChRs in oocytes (Kuryatov et al., 2000), but the linker overcomes this. Trimers of β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2 or β3(AGS)12α6(AGS)12β2 do not form functional AChRs alone. β3(AGS)12α4(AGS)12β2 plus free α6 and β2 forms functional AChRs with essentially the same sensitivities to agonists as does the β3-α4 dimer or β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 pentamer. Thus, it seems likely that the subunits assemble in similar order unencumbered by their linkers in all three cases. Likewise, the β3-α6-β2 trimer combined with the α4-β2 dimer result in the same sensitivities as the β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 pentamer, implying that they assemble in the same subunit order, unencumbered by their linkers. Reducing the linker length to (AGS)6 in the β3-α6-β2 trimer and α4-β2 dimer still permits assembly of functional AChRs, but constraints of the short linkers reduce agonist sensitivities by 2 orders of magnitude. β3 subunits can form functional AChRs only by assembling as an accessory subunit. If β3 is covalently linked to α4 or α6, it is very likely to assemble as an accessory subunit adjacent to that subunit. The difference in length between a linker of (AGS)6 and (AGS)12 constrains the ability of subunit pairs to assemble. An (AGS)12 linker allows a β2 subunit to assemble on either side of an α4 subunit, to act either as an accessory subunit or to form an ACh binding site with the linked subunit. For β3 linked to an α to assemble as an accessory subunit with another α would require the linker to extend past one or two other subunits. This seems likely to be inhibited by even an (AGS)12 linker. Thus, although the linear order in which subunits are linked does not absolutely determine the order in which they assemble, especially in the case of β3-α4 or β3-α6 pairs, it seems very likely that linkage order determines order of assembly of subunits around the mature AChR.

Expression of concatameric α6* AChRs was reproducible, as indicated by the standard errors on the EC50 values for agonists (Tables 2 and 3). As a further example of reproducibility, consider responses of concatameric pentamers. Sets of 30 to 40 oocytes were injected with concatamers on more than 20 occasions. Always, more than 90% of oocytes gave significant currents.

TABLE 3.

Agonist sensitivities of α6β2β3* AChR subtypes

Values are presented ± S.E.

| Concatamer | ACh | Nicotine | Varenicline | Cytisine | Sazetidine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 | |||||

| EC50 (μM) | 1.21 ± 0.09 | 0.387 ± 0.051 | 0.178 ± 0.107 | 0.110 ± 0.029 | 0.157 ± 0.040 |

| n = 6 | n = 5 | n = 4 | n = 5 | n = 4 | |

| nH | 1.03 ± 0.07 | 1.06 ± 0.11 | 0.895 ± 0.245 | 1.13 ± 0.19 | 0.770 ± 0.095 |

| Efficacy | ≡1 | 0.244 ± 0.009 | 0.0658 ± 0.0089 | 0.0616 ± 0.0053 | 0.219 ± 0.015 |

| β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 | |||||

| EC50 (μM) | 0.828 ± 0.047 | 0.170 ± 0.079 | 0.0747 ± 0.0329 | 0.111 ± 0.020 | 0.0199 ± 0.0048 |

| n = 5 | n = 4 | n = 7 | n = 9 | n = 4 | |

| nH | 1.11 ± 0.06 | 1.12 ± 0.49 | 0.997 ± 0.182 | 0.718 ± 0.085 | 0.939 ± 0.054 |

| Efficacy | ≡1 | 0.788 ± 0.095 | 0.276 ± 0.040 | 0.183 ± 0.006 | 0.863 ± 0.105 |

| β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 | |||||

| EC50 (μM) | 1.76 ± 0.25 | 0.397 ± 0.122 | 0.134 ± 0.025 | 0.238 ± 0.025 | 0.0445 ± 0.0087 |

| n = 5 | n = 4 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 4 | |

| nH | 0.906 ± 0.092 | 1.14 ± 0.15 | 0.889 ± 0.052 | 0.911 ± 0.072 | 0.854 ± 0.046 |

| Efficacy | ≡1 | 0.583 ± 0.073 | 0.167 ± 0.010 | 0.193 ± 0.004 | 0.732 ± 0.048 |

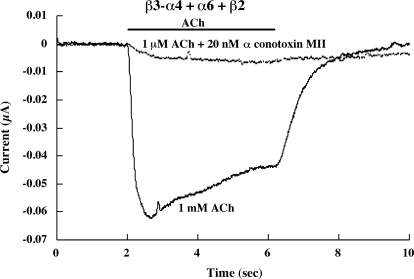

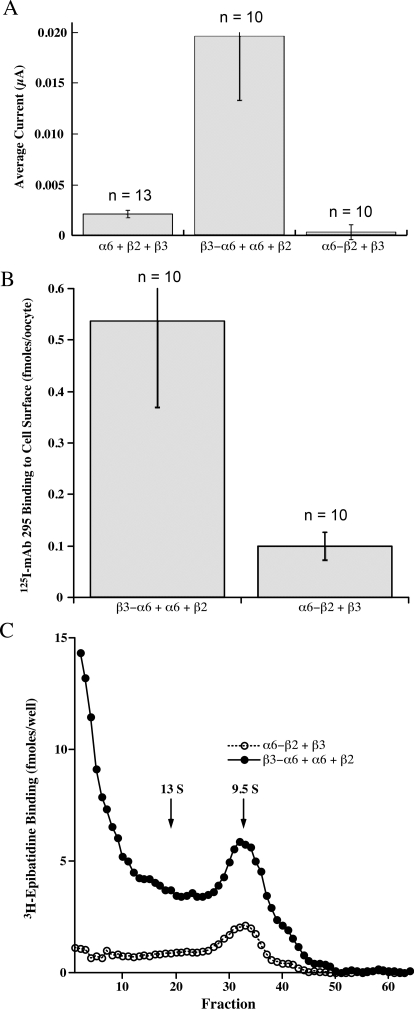

A single linked β3-α4 subunit pair prevents assembly of (α4β2)2β3 AChRs and permits assembly of β3-(α4β2)(α6β2) AChRs when expressed with free α6 and β2 subunits (Table 2). This shows that when the β3 accessory subunit is fixed in place by a linker, α4β2 and α6β2 ACh binding sites can form from free subunits. All of the AChRs formed contain (α6β2) binding sites, as shown by the ability of α conotoxin MII to block function (Fig. 6). α6 and β2 alone efficiently form ACh binding sites but not mature pentameric AChRs (Kuryatov et al., 2000). A β3-α6 concatamer in combination with α6 and β2 subunits permits formation of significant amounts of functional mature β3-(α6β2)(α6β2) AChRs (Fig. 7). This was demonstrated by assembly of [3H]epibatidine-labeled AChRs of the size expected for mature AChRs (Fig. 7C), their expression on the cell surface (Fig. 7B), and their function in response to ACh (Fig. 7A). Linking of β3 to α6 was critical for assembly of functional pentamers. Linkage of α6 to β2 and free β3 was not effective (Fig. 7). Assembly of the β3 accessory subunit in α6β2β3* AChRs seems to require a special chaperone. A single concatameric linkage between β3 and α4 or α6 subunits can replace this function.

Fig. 6.

α Conotoxin MII (20 nM) blocks the response to 1 μM ACh of β3-(α4β2)(α6β2) AChRs formed from coexpression of the β3-α4 concatamer plus free α6 and β2 subunits. This proves that this response results from AChRs with an ACh binding site formed by an α6β2 subunit pair, because α conotoxin MII blocks α6β2 binding sites not α4β2 binding sites. The β3-α4 concatamer would not be expected to assemble mature AChRs in combination with just β2, and it did not.

Fig. 7.

Linking β3 to α6 results in formation of functional AChRs in combination with β2. A, the combination of α6 + β2 + β3 subunits produces negligible currents in response to 30 μM ACh. The β3-α6 concatamer in combination with free α6 and β2 subunits produces substantial currents in response to ACh. The α6-β2 concatamer in combination with β3 subunits produces no response. B, the β3-α6 concatamer expressed with free α6 and β2 subunits resulted in expression of abundant AChRs on the oocyte surface detected by binding of an iodinated mAb to the extracellular surface of β2 subunits. The α6-β2 concatamer in combination with β3 produced few AChRs on the cell surface. C, the β3-α6 concatamer expressed with free α6 and β2 subunits resulted in expression of many mature pentameric AChRs the size of 9.5 S T. californica AChR monomers that could be solubilized with Triton X-100, sedimented on sucrose gradients, immunoisolated, and labeled with [3H]epibatidine. In addition, large amounts of improperly assembled subunits formed large aggregates. Only epibatidine binding aggregates are found in oocytes that express only free α6 and β2 subunits (Kuryatov et al., 2000). Here they may result from excess free α6 and β2 subunits over those that assemble properly with the β3-α6 concatamer. The α6-β2 concatamer in combination with free α6 and β3 subunits formed a small amount of AChRs that sedimented at the rate expected of mature pentameric AChRs, and a small proportion of aggregates capable of binding epibatidine. The small amount of mature AChRs results from inefficient incorporation of free β3. The low amount of epibatidine-labeled aggregates suggests that the α6-β2 concatamer does not efficiently form epibatidine binding sites in aggregates that are probably present. Collectively, these three panels show that proper assembly of the β3 accessory subunit with α6 is critical to assembly of functional α6β2β3 AChRs and that a single concatameric linkage of β3 with α6 permits this assembly, allowing association of free β2 and α6 subunits to complete assembly of functional pentamers. This concatameric linkage may replace the effect of a specialized chaperone protein found in cells that endogenously express α6β2β3 AChRs.

β3-(α4β2)(α6β2) AChRs are sensitive to activation (EC50 = 0.584 ± 0.149 for nicotine, n = = 8) (Table 2), more sensitive than (α4β2)2β3 AChRs (EC50 = 1.78 ± 0.7 for nicotine, n = 4) (Kuryatov et al., 2008). A β3 or an α4 accessory subunit greatly reduces sensitivity when two (α4β2) ACh binding sites are in the AChR compared with (α4β2)2β2 AChR. However, a β3 accessory subunit adjacent to α4 allows high sensitivity to activation when both an (α4β2) and an (α6β2) ACh binding site are present (Table 2). The sensitivity to activation remains high if the subunit composition is kept the same, but the subunit order is changed so that β3 is next to α6 (Tables 2, 3). Thus, the sensitivity to activation results not from the specific association of an accessory subunit next to a particular α subunit, but from global conformation changes involving all of the subunits in the AChR.

Construction of the (α4β2)(α6β2)β3 subtype using the trimeric concatamer β3-α4-β2 + α6 + β2 produces AChRs with essentially the same ACh sensitivity (EC50 = 1.11 ± 0.09 μM, n = 4) as using the dimeric concatamer β3-α4 (EC50 = 1.69 ± 0.14 μM, n = 6) (Table 2). The pentameric concatamer β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 is similarly ACh sensitive (EC50 = 1.76 ± 0.25 μM, n = 5) (Table 2). Because the same subtype formed containing 1, 2, or 4 (AGS)x linkers has the same sensitivities to agonists, these linkers do not significantly alter functional properties.

Concatamers permit changing subunit order within the same subunit stoichiometry. The (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 subtype was constructed in two ways, either as a concatameric pentamer or as a combination of a β3-α6-β2 trimer plus an α4-β2 dimer (Table 2). Their properties were similar, and both are somewhat more sensitive to activation than the (α4β2)(α6β2)β3 subtype. Both were completely blocked by α-conotoxin MII. Because β3 and α6 are uniquely expressed together in aminergic neurons, it would be surprising if they were not adjacent in AChRs of aminergic neurons.

(α6β2)2β3 AChRs were the most difficult to express. β3-α6 plus α6 + β2 formed few functional AChRs (Fig. 7). The pentameric concatamer β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 produced more functional AChRs. These were similarly sensitive to activation as were the other α6β2β3* AChR subtypes (Table 2 and Fig. 8). Large numbers of ACh binding sites were produced (Fig. 9). These were all assembled into a homogeneous population of the size expected of mature AChRs (Fig. 10A). However, only a very small proportion of (α6β2)2β3 concatamer was expressed on the cell surface (Fig. 11). All of the concatamers formed components of the expected sizes on Western blots (Fig. 12). This indicates that the concatamers were stable and not proteolyzed into free subunits. Function of all of the α6* concatamers was completely blocked by α conotoxin MII (Fig. 13). This indicates that all depended on α6β2 ACh binding sites for their function. The inefficiency with which (α6β2)2β3 AChRs were transported to the cell surface suggests that α6* AChRs may interact with a special transporter in aminergic neurons that is not present in oocytes. The presence of a single α4 subunit confers efficient transport to the surface. A single α3 subunit probably is similarly effective (Kuryatov et al., 2000). It is likely that cytoplasmic domain sequences are recognized by such transport systems.

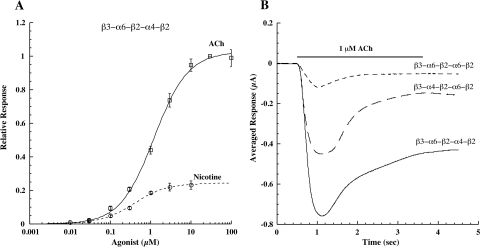

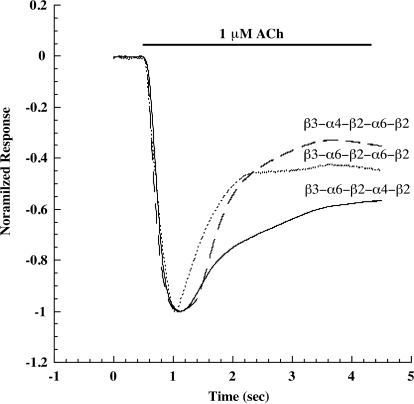

Fig. 8.

Agonist responses of pentameric concatamer α6β2β3* AChRs. A, dose/response curves for β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 show that nicotine is a partial agonist. B, the amplitude of response to 1 μM ACh is greatest for β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 AChRs and least for β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 AChRs. The small amplitude of β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 response reflects the small number of these AChRs that are transported to the cell surface, as will be shown subsequently. The kinetics of desensitization of all three concatameric pentamers are similar. Thus neither the presence nor absence of α4, or whether β3 is adjacent to α6 or α4, greatly alters the kinetics of these responses.

Fig. 9.

Concatameric pentamers form large numbers of ACh binding sites labeled with [3H]epibatidine. Oocytes were injected with 20 ng of mRNA for β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 or β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 or 90 ng of mRNA for β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 (to compensate for its low surface expression). AChRs were extracted with Triton X-100, immune-isolated using mAb 295 to β2 subunits, then labeled with [3H]epibatidine. β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 resulted in the formation of very large amounts of [3H]epibatidine binding sites, primarily reflecting the large amount of mRNA expressed. As will be shown subsequently, these binding sites are primarily in pentameric AChRs that have not been efficiently transported to the cell surface.

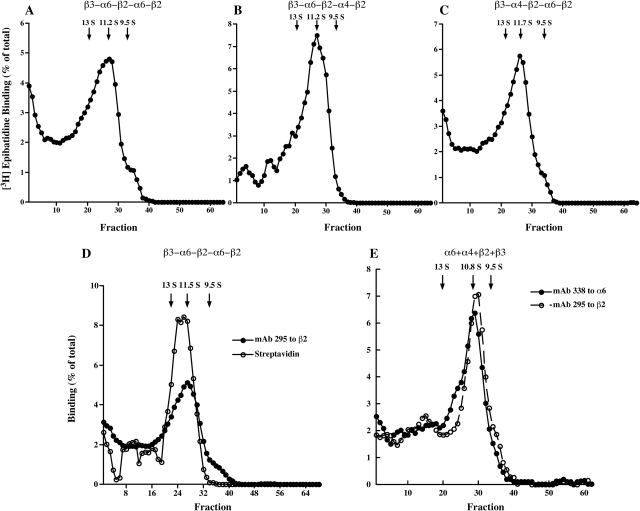

Fig. 10.

Concatameric pentamers sediment on sucrose velocity gradients as components of the expected size, intermediate between that of T. californica AChR monomers (9.5 S) and dimers (13 S). Fractions are numbered from the bottom of the gradients up. α6β2β3* AChRs in each gradient fraction were isolated using microwells coated with mAb 295 to β2 subunits, then labeled with [3H]epibatidine. α1β1γδ T. californica AChRs were used as internal standards on each gradient. They were isolated using microwells coated with mAb 210 to α1 subunits, then labeled with 125I-α-bungarotoxin. Only the locations of the peaks corresponding to T. californica monomers and dimers are shown. A, β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 concatamers assemble primarily into mature AChRs somewhat larger than T. californica AChR monomers, although a few form larger aggregates. B, β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 concatamers assemble almost exclusively into mature AChRs, with few larger aggregates being formed. C, β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 concatamers assemble primarily into mature AChRs, although a small amount form larger aggregates. Subunit order or composition do not seem to have large effects on efficiency of assembly of pentameric concatamers into mature AChRs. D, oocytes expressing β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 were surface labeled with biotin. After extraction with Triton X-100 and sedimentation, aliquots of each fraction were isolated on microwells coated with either mAb 295 to bind β2 or streptavidin to bind biotinylated AChR, and then labeled with [3H]epibatidine. This shows that surface AChRs have the same size as intracellular AChRs. E, a human embryonic kidney cell line transfected with α6, α4, β2, and β3 subunits was extracted with Triton X-100, sedimented on a sucrose gradient, aliquots of each fraction were isolated on microwells coated with either mAb 295 to β2 subunits or mAb 338 to α6 subunits, finally, AChRs were labeled with [3H]epibatidine. This shows that both α6β2* and α4β2* AChRs formed from free subunits sediment at nearly the size of the concatamers. The concatamers sediment slightly more rapidly, probably because of the mass of the linkers.

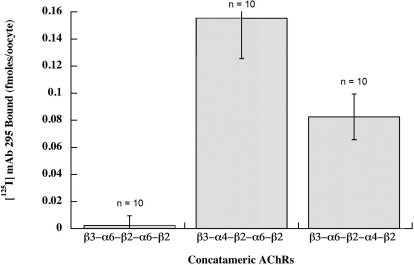

Fig. 11.

Amount of pentameric concatamer AChRs on the oocyte surface was assayed by binding of 125I-mAb 295 to the extracellular surface of β2 subunits. These oocytes were injected with 20, 20, and 90 ng of mRNA, as in Fig. 9. Despite the large amount of mRNA for β3-α6-β2-α6-β2, the large number of epibatidine binding sites formed (Fig. 9) and their efficient assembly into mature AChRs (Fig. 10), very few are expressed on the cell surface. This suggests that the presence of an α4 subunit in α6β2β3* AChRs is critical for their efficient transport to the surface of the oocyte.

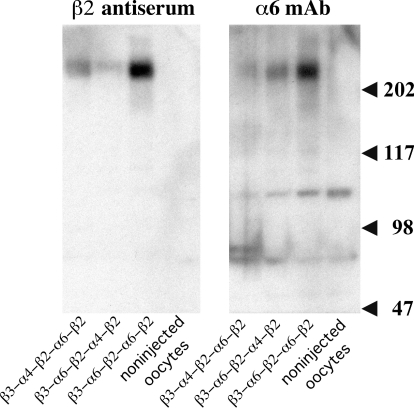

Fig. 12.

Concatameric pentamers expressed in oocytes are not cleaved by proteases into free subunits. Western blots reveal proteins of the sizes expected of the concatamers (>2 × 105 Da) and no free subunits (∼5 × 104 Da). Proteolysis to unlinked subunits does not occur in the oocytes, consistent with our experience with α4β2 dimers (Zhou et al., 2003) and the experience of others with α4β2 pentamers formed using the same (AGS)x linker system (Carbone et al., 2009). β2 was localized on the blots with antiserum to bacterially expressed (denatured) β2 subunits because mAb 295 binds only to native β2, preferentially in combination with an α subunit. α6 was localized using mAb 349 (Tumkosit et al., 2006). Large amounts of β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 protein are formed as a result of 90 ng of this mRNA and only 20 ng of the others. Likewise, large amounts of epibatidine binding sites were observed with this chimera in Fig. 9. These were efficiently assembled into mature AChRs (Fig. 10A), some of which were expressed on the cell surface (Fig. 10D). However, only a very few β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 AChRs were transported to the cell surface (Fig. 11). Consequently, the amplitude of their response is low compared with those of the other concatamers (Fig. 8).

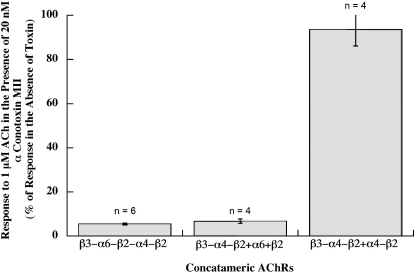

Fig. 13.

α-Conotoxin MII blocks the function of (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChRs but not (α4β2)2β3 AChRs. Responses to 1 μM ACh were assayed with or without 20 nM α-conotoxin MII. The (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChR subtype was expressed both as a concatameric pentamer (β3-α6-β2-α6-β2) and as a mixture of concatameric trimer and free subunits (β3-α4-β2 + α6 + β2). In both cases, the toxin blocked the response to ACh virtually completely. The (α4β2)2β3 subtype was expressed using a concatameric trimer and dimer (β3-α4-β2 + α4-β2). Its response to ACh was virtually unaffected by the toxin. Thus, the presence of a single α6β2 binding site, whether or not the α6 is adjacent to β3, is sufficient to allow high potency blockage by α conotoxin MII.

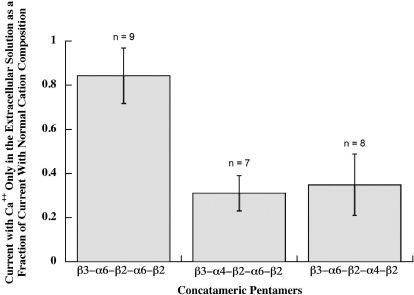

Comparing the properties of α6β2β3* AChR subtypes using pentameric concatamers, the (α6β2)2β3 subtype was found to have ≥2.5-fold the Ca2+ permeability of either the (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 subtype or the (α4β2)(α6β2)β3 subtype (Fig. 14). This Ca2+ permeability is greater than that of (α4β2)2β2 (9.5-fold), (α4β2)2α4 (4-fold), (α4β2)2β3 (2.8-fold), or (α4β2)2α5 (1.7-fold) (Tapia et al., 2007). The high Ca2+ permeability conferred on α4β2* AChRs by α4, α5, and β3 was mapped to Glu 262 near the C-terminal end of the M2 channel lining sequence in these subunits, compared with Lys at this position in β2 (Tapia et al., 2007). α6 also has a Glu at this position, so this cannot account for why having two α6 subunits results in higher Ca2+ permeability than either one α6 and one α4 or two α4.The (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 subtype was found to desensitize somewhat more slowly than the other two α6β2β3* AChR subtypes (Fig. 15). These features no doubt factor, along with drug sensitivities and the proportion of each subtype, in the differences in physiological responses associated with different populations of dopaminergic neurons (Gotti et al., 2010). The high Ca2+ permeability of (α6β2)2β3 AChRs may be especially important for promoting release of dopamine at nerve endings.

Fig. 14.

Ca2+ permeability of pentameric concatamers. Responses to 30 μM ACh were assayed both with normal cation concentrations, that would allow extracellular Na+, K+, Mg2+, or Ca2+ to flow through AChRs, and with 1.8 mM Ca2+ as the only extracellular cation, so that current flow through AChRs resulted only from Ca2+. Both β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 and β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 pentameric concatamers showed substantial permeability to Ca2+. Thus, subunit composition, but not subunit order, is important for high Ca2+ permeability of (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChRs. (α6β2)2β3 AChRs formed from the β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 concatamer were 3-fold more selective for Ca2+. Currents when only 1.8 mM Ca2+ was present were 80% of the total cation current when other cations were present. This compares with 8.4% for (α4β2)2β2, 20% for (α4β2)2α4, or 48% for (α4β2)2α5 in the same assay (Tapia et al., 2007). It should be noted that responses for the β3-α6-β2-α6-β2 concatamer were assayed at −70 mV to increase the response from the small amount of these AChRs on the cell surface, and this might increase the Ca2+ permeability relative to the other subtypes that were assayed at −50 mV.

Fig. 15.

Desensitization of α6β2β3* AChRs by 1 μM ACh. Concatameric pentamers were used to express three subtypes. The maximum responses were normalized to facilitate comparison of the rates and extents of desensitization. (α6β2)2β3 desensitizes most rapidly. (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 desensitizes more slowly and to the least extent, even though it is most sensitive to agonists. However, there are not dramatic differences in the kinetics of the three subtypes.

The agonist sensitivities of α6β2β3* AChR subtypes were compared using concatameric pentamers (Table 3). All were relatively sensitive to activation. The EC50 for nicotine-induced release of dopamine from striatal synaptosomes of ACh subtypes inferred from knockout mice were 1.52 ± 0.19 μM for (α6β2)2β3 and 0.23 ± 0.08 μM for (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 (Salminen et al., 2007). Similar EC50 values for activation by nicotine were observed for human concatameric AChRs of these subtypes: β3-α6-β2-α6-β2, 0.387 ± 0.051 μM, n = 5; and β3-α6-β2-α4-β2, 0.170 ± 0.079 μM, n = 4. Without question, IC50 values for desensitization are much lower. Activation and desensitization of these subtypes are clearly relevant to the 0.1 to 0.2 μM nicotine concentrations sustained in smokers (Benowitz, 1996). Their sensitivities to nicotine-induced up-regulation are lower, with EC50 values of 9.84 ± 0.03 μM for α6β2 and 0.89 ± 0.29 μM for α6β2β3 (Tumkosit et al., 2006). These sensitivities reflect the affinities of α6β2 pairs in partially assembled AChRs on which nicotine acts as a pharmacological chaperone to promote further assembly (Kuryatov et al., 2005). The assembly of the accessory subunit may be rate-limiting in forming mature AChRs. The presence of β3 accessory subunits increased both the amount of AChRs assembled and the sensitivity to increase in the amount in the presence of nicotine (Tumkosit et al., 2006). In complex α6β2β3* AChR subtypes, whether β3 is next to α6 or α4 has surprisingly little effect on agonist sensitivity. It is notable that the putatively highly α4β2-selective agonists varenicline, cytisine, and sazetidine all are very potent at activating α6β2β3* AChRs. All are partial agonists. Their efficacies in some cases are quite low [e.g., 0.07 for varenicline on (α6β2)2β3 AChRs]. However, varenicline is 4-fold more efficacious on (α6β2) (α4β2)β3 and very potent (EC50 = 0.074 ± 0.0329 μM, n = 7). Sazetidine is highly potent on (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 (EC50 = 0.0199 ± 0.0048 μM, n = 4) and nearly a full agonist (efficacy = 0.86). However, at sustained therapeutic concentrations, these drugs are likely to be very potent desensitizers of α6β2β3* AChRs.

Discussion

Expression of functional cloned human α6β2β3* AChR subtypes has been achieved by using concatamers to compensate for special chaperones that may be required for their assembly. The (α6β2)2β3 subtype was not efficiently transported to the cell surface, presumably because, although concatamers permitted assembly, an additional chaperone may be required to efficiently transport AChRs with two α6 subunits to the cell surface. Subtypes in which one of the α6 subunits is replaced by α3 or α4 are efficiently transported, so the presence of a single α3 or α4 subunit seems to be all that is required.

Assembly of the accessory subunit seems to be the limiting step in assembly of mature functional AChRs. α6 and β2 assemble very efficiently to form dimers that form ACh binding sites, and these form tetramers and larger aggregates. A single pair of linked subunits including the β3 accessory subunit (β3-α6 or β3-α4) is sufficient to insure efficient assembly of β3-(α6β2)2 AChRs or β3-(α4β2)(α6β2) AChRs.

Concatameric β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 pentamers with four linkers have the same pharmacological properties as concatamers with 1, 2, or 3 linkers. Thus, the presence of multiple (AGS)x linkers of these lengths does not alter pharmacological properties.

β3-α6-β2-α4-β2 AChRs were more sensitive to agonists than were β3-α4-β2-α6-β2 AChRs but not remarkably so. One might expect that the subunit order in dopaminergic neurons would be β3(α6β2)(α4β2) rather than β3(α4β2)(α6β2), because the accessory subunit β3 and α6 are uniquely coexpressed in aminergic neurons and usually part of the same AChRs. β3 and α6 are adjacent in the genome, probably reflecting transcriptional coregulation. Likewise, α3, β4, and α5 subunits are adjacent in the genome and coassembled in autonomic neurons. β3 and α5 are closely related in sequence and both function only as accessory subunits. The special chaperone that promotes assembly of β3 accessory subunits to form mature β3α6* AChR pentamers probably insures the β3α6 subunit order, but it would not make much difference if it did not. β3 assembles spontaneously with α4 very efficiently, apparently more efficiently than either β2 or α4, because transfection of an α4β2 cell line that expresses a mixture of (α4β2)2β2 and (α4β2)2α4 AChRs results in assembly of 25-fold more AChRs, all (α4β2)2β3, to the limit of the amount of α4 expressed in the line (Kuryatov et al., 2008). It is more efficient in this respect than α5 subunits.

Formation of AChR subunit concatamers using (AGS)n linkers between the C-terminal amino acid of one subunit and the N-terminal amino acid of the next subunit results in expression by X. laevis oocytes of the expected concatameric proteins, which remain intact and are not cleaved into their component subunits, as demonstrated by Western blot analysis (Zhou et al., 2003; Carbone et al., 2009; Fig. 12). The length of the linker depends on both the length of the short extracellular C-terminal sequence after M4 and the (AGS)n linker itself. Use of the shorter linker (AGS)6 and the shorter C terminus of α4 (8 amino acids) rather than the relatively long C terminus of β2 (23 amino acids) can constrain whether the subunit pair assembles to form an ACh binding site within the linked α4β2 pair or between adjacent subunits (Zhou et al., 2003). All of the pentameric concatamers reported here used (AGS)12 linkers, except after β2, where (AGS)6 sufficed. The use of only (AGS)6 linkers hampered assembly and greatly reduced sensitivity to activation (Table 2). Concatamers formed by linking the C terminus of one AChR subunit to the N-terminal end of the signal sequence of the next subunit through (Q)n linkers results in lower levels of expression and degradation of concatamers to their component subunits (Groot-Kormelink et al., 2004, 2006). The degradation may result from the presence of the endogenous protease sites in the signal sequences.

α6β2β3* AChR subtypes do not differ remarkably in kinetics of desensitization. The (α6β2)2β3 subtype desensitizes most rapidly. It is substantially more Ca2+-permeable than the other α6β2β3* AChR subtypes, or α4β2* AChR subtypes, which may give it substantial impact on dopamine release at nerve endings. The (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 subtype desensitizes more slowly and to the least extent. In combination with the fact that it is the most sensitive to agonists, this may give it substantial impact in response to both endogenous ACh and drugs. Cholinergic modulation of locomotion and striatal dopamine releases through α6* AChRs is thought to be mediated by these subtypes (Drenan et al., 2010). The EC50 for nicotine-induced dopamine release from mouse synaptosomes attributed to this subtype (0.23 ± 0.08 μM) (Salminen et al., 2007) is similar to that for activation of this human subtype by nicotine (0.170 ± 0.079 μM, n = 4) reported here.

α6β2β3* AChRs are remarkably sensitive to activation by nicotine and drugs used for smoking cessation therapy. Both varenicline and sazetidine inhibit self-administration of both nicotine and alcohol (Ericson et al., 2009; Rezvani et al., 2010). These were developed as α4β2-selective drugs. Nicotine is slightly less potent on human (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChRs (EC50 = 0.17 ± 0.079 μM, n = 4) than on (α4β2)2β2 AChRs (EC50 = 0.116 ± 0.015 μM) and much more potent than on (α4β2)2β3 (EC50 = 1.78 ± 0.70 μM) or (α4β2)2α4 AChRs (EC50 = 2.7 ± 0.20 μM) (Kuryatov et al., 2008). Relative IC50 values reflecting desensitization after sustained exposure may ultimately be more important [IC50 = 0.0061 ± 0.0036 μM, n = 4 for (α4β2)2β2 and (α4β2)2α4, but not yet determined for α6β2β3* AChRs] (Kuryatov et al., 2008). Sazetidine is remarkably potent as an agonist (EC50 = 0.0199 ± 0.0048 μM, n = 4) on (α6β2)(α4β2)β3). It is probably also much more potent as a desensitizing antagonist. Its efficacy on short-term exposure is quite high (0.863), although that may be irrelevant as a drug in vivo, where desensitization would dominate its effects. This is probably true for varenicline as well (EC50 = 0.0747 ± 0.0329 μM, n = 7), the efficacy of which is lower (0.276). Much of the beneficial effects of drugs for smoking cessation may be mediated by their desensitizing effects (Levin et al., 2010). The overlap between their dose/response curves for activation and desensitization designates the concentration range in which there is some smoldering activation on long-term exposure to nicotine. The extent of this smoldering activation can vary widely depending on AChR subtypes (Olale et al., 1997; Kuryatov et al., 2011; A. Kuryatov, B. Campling, and J. Lindstrom, unpublished observations). The extent of smoldering activation of full and partial agonists currently used for smoking cessation therapy, as well as their effects on multiple AChR subtypes may lead to the effects that limit their use (e.g., nausea, unusual dreams).

Antagonists selective for α6β2β3* AChRs may be effective for smoking cessation and avoid the side effects of drugs that can activate and desensitize multiple AChR subtypes. Knockout of α6 subunits in the ventral tegmental area prevents nicotine self-administration, as does knockout of α4 or β2 subunits (Pons et al., 2008). Knockout of any of these subunits would prevent synthesis of (α6β2)(α4β2)β3 AChRs in ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons. Application of α conotoxin MII to the amygdala prevents the rewarding effects of nicotine (Jackson et al., 2009; Brunzell et al., 2010). It would block α6β2β3* AChRs on the endings of dopaminergic neurons projecting from the ventral tegmental area. bPiDDB and r-bPiDDB are α6* AChR-selective antagonists that potently inhibit nicotine-induced dopamine release and inhibit self-administration of nicotine (Smith et al., 2010). α6 antagonists may also be anxiolytic, because knockout of β3 subunits reduces α6 expression and reduces anxiety (Cui et al., 2003; Salminen et al., 2004).

Positive allosteric modulators or agonists selective for α6β2β3* AChRs may be useful in treating Parkinson's disease, and be more effective than nicotine. AChR agonists have been proposed for treatment of Parkinson's disease (Quik and McIntosh, 2006). Smoking reduces the incidence of Parkinson's disease. This probably results from neuroprotective effects of nicotine (which can be demonstrated in vitro), because AChRs promote release of dopamine, and because loss of dopaminergic neurons is the fundamental lesion in Parkinson's disease. Agonists or positive allosteric modulators selective for α6β2β3* AChRs could have the desired effects without effecting many AChR subtypes. Although hyperactive α6* AChRs produce hypermobility (Drenan et al., 2008a), neither knockout of α6* AChRs nor localized α6* AChR antagonism produces Parkinsonian effects (Champtiaux et al., 2003; Gotti et al., 2010). Expression of functional human α6β2β3* AChR subtypes, as we have demonstrated here, provides a critical detection system needed to develop drugs selective for α6β2β3* AChRs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Barbara Campling for her comments on the manuscript and Jong-Hoon Lee for technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [Grant NS11323].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/mol.110.066159.

- AChR

- acetylcholine receptor

- ACh

- acetylcholine

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- mAb

- monoclonal antibody

- LB

- Luria broth

- AGS

- alanine, glycine, serine.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Lindstrom and Kuryatov.

Conducted experiments: Kuryatov.

Performed data analysis: Kuryatov.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Lindstrom and Kuryatov.

Other: Lindstrom acquired funding for the research.

References

- Benowitz NL. (1996) Pharmacology of nicotine: addiction and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 36:597–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Boschen KE, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM, McIntosh JM. (2010) α-Conotoxin MII-sensitive nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell regulate progressive ratio responding maintained by nicotine. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:665–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carbone AL, Moroni M, Groot-Kormelink PJ, Bermudez I. (2009) Pentameric concatenated (α4)2(β2)3 and (α4)3(β2)2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: subunit arrangement determines functional expression. Br J Pharmacol 156:970–981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Gotti C, Cordero-Erausquin M, David DJ, Przybylski C, Léna C, Clementi F, Moretti M, Rossi FM, Le Novère N, et al. (2003) Subunit composition of functional nicotinic receptors in dopaminergic neurons investigated with knock-out mice. J Neurosci 23:7820–7829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champtiaux N, Han ZY, Bessis A, Rossi FM, Zoli M, Marubio L, McIntosh JM, Changeux JP. (2002) Distribution and pharmacology of α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed with mutant mice. J Neurosci 22:1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C, Booker TK, Allen RS, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, Marks MJ, Salminen O, Tritto T, Butt CM, Allen WR, et al. (2003) The β3 nicotinic receptor subunit: a component of α-conotoxin MII-binding nicotinic acetylcholine receptors that modulate dopamine release and related behaviors. J Neurosci 23:11045–11053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell C, Olivera BM, Garrett JE, Staheli ST, Watkins M, Kuryatov A, Yoshikami D, Lindstrom JM, McIntosh JM. (2003) α-Conotoxin PIA is selective for α6 subunit-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 23:8445–8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Steele AD, McKinney S, Patzlaff NE, McIntosh JM, Marks MJ, Miwa JM, Lester HA. (2010) Cholinergic modulation of locomotion and striatal dopamine release is mediated by α6α4* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci 30:9877–9889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Grady SR, Whiteaker P, McClure-Begley T, McKinney S, Miwa JM, Bupp S, Heintz N, McIntosh JM, Bencherif M, et al. (2008a) In vivo activation of midbrain dopamine neurons via sensitized, high-affinity α6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Neuron 60:123–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Nashmi R, Imoukhuede P, Just H, McKinney S, Lester HA. (2008b) Subcellular trafficking, pentameric assembly, and subunit stoichiometry of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing fluorescently labeled α6 and β3 subunits. Mol Pharmacol 73:27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Löf E, Stomberg R, Söderpalm B. (2009) The smoking cessation medication varenicline attenuates alcohol and nicotine interactions in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 329:225–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerzanich V, Kuryatov A, Anand R, Lindstrom J. (1997) “Orphan” α6 nicotinic AChR subunit can form a functional heteromeric acetylcholine receptor. Mol Pharmacol 51:320–327 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Guiducci S, Tedesco V, Corbioli S, Zanetti L, Moretti M, Zanardi A, Rimondini R, Mugnaini M, Clementi F, et al. (2010) Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the mesolimbic pathway: primary role of ventral tegmental area α6β2* receptors in mediating systemic nicotine effects on dopamine release, locomotion, and reinforcement. J Neurosci 30:5311–5325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Gaimarri A, Zanardi A, Clementi F, Zoli M. (2007) Heterogeneity and complexity of native brain nicotinic receptors. Biochem Pharmacol 74:1102–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot-Kormelink PJ, Broadbent S, Beato M, Sivilotti LG. (2006) Constraining the expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by using pentameric constructs. Mol Pharmacol 69:558–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groot-Kormelink PJ, Broadbent SD, Boorman JP, Sivilotti LG. (2004) Incomplete incorporation of tandem subunits in recombinant neuronal nicotinic receptors. J Gen Physiol 123:697–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KJ, McIntosh JM, Brunzell DH, Sanjakdar SS, Damaj MI. (2009) The role of α6-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in nicotine reward and withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 331:547–554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuryatov A, Berrettini W, Lindstrom J. (2011) Acetylcholine receptor (AChR) α5 subunit variant associated with risk for nicotine dependence and lung cancer reduces (α4β2)α5 AChR function. Mol Pharmacol 79:119–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]