Abstract

Histamine H3 receptors (H3Rs), distributed within the brain, the spinal cord, and on specific types of primary sensory neurons, can modulate pain transmission by several mechanisms. In the skin, H3Rs are found on certain Aβ fibers, and on keratinocytes and Merkel cells, as well as on deep dermal, peptidergic Aδ fibers terminating on deep dermal blood vessels. Activation of H3Rs on the latter in the skin, heart, lung, and dura mater reduces calcitonin gene-related peptide and substance P release, leading to anti-inflammatory (but not antinociceptive) actions. However, activation of H3Rs on the spinal terminals of these sensory fibers reduces nociceptive responding to low-intensity mechanical stimuli and inflammatory stimuli such as formalin. These findings suggest that H3R agonists might be useful analgesics, but these drugs have not been tested in clinically relevant pain models. Paradoxically, H3 antagonists/inverse agonists have also been reported to attenuate several types of pain responses, including phase II responses to formalin. In the periaqueductal gray (an important pain regulatory center), the H3 inverse agonist thioperamide releases neuronal histamine and mimics histamine's biphasic modulatory effects in thermal nociceptive tests. Newer H3 inverse agonists with potent, selective, and brain-penetrating properties show efficacy in several neuropathic and arthritis pain models, but the sites and mechanisms for these actions remain poorly understood.

Histamine and Pain

Histamine, found throughout the body in both neuronal and non-neuronal sources, can modify pain transmission by actions at multiple receptors in the skin, spinal cord, and brain. Rapidly expanding information on the distribution and functions of H3 receptors (H3Rs) and the recent development of new H3R ligands have heightened interest in the possible modulation of pain by H3R-acting drugs. The present article provides a short, integrative overview of relevant studies (for review see also Sander et al., 2008; Tiligada et al., 2009; Gemkow et al., 2009).

Measuring Pain in the Laboratory

Pain, which can be defined as the central representation of tissue-damaging stimuli with sensory-discriminative, motivational, and cognitive components (Besson and Chaouch, 1987), is readily understood by humans as a sensory experience. Ideally, evaluation of the pain-relieving properties of drugs should directly measure reductions in pain perception. Instead, assessment of analgesic drug action in nonverbal subjects relies heavily on measures of behavioral, often reflexive, responses. Because drugs can modify these responses (but not necessarily the underlying perceptions), results from pain testing in laboratory animals can be misleading. The present limitations of preclinical methodologies for identifying pain-relieving drugs have been discussed previously (Rice et al., 2008; Vierck et al., 2008).

Notwithstanding the limitations in state-of-the-art analgesic testing, many factors must be considered when evaluating the literature on the analgesic potential of H3R-acting drugs. As discussed below, the nature of the nociceptive stimulus (heat, pressure, chemicals), the characteristics of the stimulus (location, intensity, chronicity), and pathophysiological status of the subject all are critical variables (Le Bars et al., 2001). Finally, pharmacological variables add additional layers of complexity. These include receptor selectivity, sites of action (peripheral, spinal, brain), and dose-response characteristics.

Pharmacology of H3R-Acting Drugs

Initially discovered as the CNS histaminergic autoreceptor (Arrang et al., 1987), the H3R is now known to be a Gi/o-coupled receptor that functions as both an auto- and hetero-receptor in the brain. Details of H3R signaling, splice variants, and pharmacology have been described previously (Hough, 2001; Leurs et al., 2005; Esbenshade et al., 2006; Bongers et al., 2007). Table 1 summarizes the H3R ligands that have been most commonly used in pain research. Early studies of H3Rs and pain used the H3 agonist R-α-methylhistamine (RAMH) and the H3 blocker thioperamide. Subsequent discovery of the potent H3 agonists imetit and immepip (Vollinga et al., 1994) facilitated ensuing pain studies. Even though thioperamide has been pivotal in H3R–pain studies (below), pharmaceutical interest in H3Rs has accelerated the development of potent, selective, brain-penetrating, H3R-blocking drugs (Leurs et al., 2005; Esbenshade et al., 2006; Sander et al., 2008; De Esch et al., 2009; Gemkow et al., 2009; Tiligada et al., 2009). As mentioned below, investigations of the pain-modulating properties of these newer compounds are only just beginning.

TABLE 1.

H3R ligands that have been commonly used in pain research

| Drug | Classification | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BP 2–94 | H3 agonist prodrug | Rouleau et al., 1997 |

| GSK189254 | H3 inverse agonista | Medhurst et al., 2008 |

| Imetit | H3 agonistb | Vollinga et al., 1994 |

| Immepip | H3 agonistb | Vollinga et al., 1994 |

| RAMH | H3 agonist | Arrang et al., 1987 |

| Thioperamide | H3 inverse agonista | Arrang et al., 1987 |

Because nearly all H3 antagonists have inverse agonist properties in vitro, the terms “antagonist” and “inverse agonist” are used interchangeably in the present work.

Has weaker, but possibly relevant, histamine H4 receptor affinity (Lim et al., 2005).

The extensive use of thioperamide, immepip, and imetit in H3R-related pain studies has been complicated by the more recent discovery that these three drugs have H4 activity. Even though the H4 affinity is lower than the respective H3 value for all three drugs (Lim et al., 2005), the former may be pharmacologically significant in some cases, especially considering the more recent interest in the H4 receptor as a target for anti-inflammatory or analgesic drug development (Hsieh et al., 2010a). Initial H4 receptor research focused on hematopoietic cells (which have the highest receptor densities), but more recent studies have identified the H4 receptor in the brain (Connelly et al., 2009; Strakhova et al., 2009). Thus, pain-related H3R functions implicated by the use of these drugs require additional validation with pharmacological and/or molecular genetic tools. The opposite point also needs to be made: all H3R-related findings with these drugs cannot be dismissed a priori based only on H4 properties. For example, immepip antinociception (discussed below) cannot be assumed to be caused by H4 receptors (Gemkow et al., 2009) when the effect is mimicked by other H3 agonists that lack H4 affinity (e.g., RAMH; Lim et al., 2005), especially when the effect is abolished in H3R knockout mice (H3KO) mice (Cannon et al., 2003).

Histamine and H3Rs in the Nervous System

Histamine in the CNS is found in both histaminergic neurons and mast cells (Hough and Leurs, 2006). The latter are bone marrow-derived secretory cells found within diencephalic structures and dura mater. The close proximity of mast cells to blood vessels has led to the suggestion that they regulate blood flow, permeability, and/or immunological access to the brain, but other physiological and pathological roles have been proposed (Hough and Leurs, 2006). In adult mammals, histaminergic neurons are localized exclusively in the tuberomammillary region of the posterior hypothalamus. Both ascending and descending projections from these cells account for the widespread distribution of fibers throughout the brain and spinal cord (Haas and Panula, 2003; Hough and Leurs, 2006). Outside the CNS, histamine is stored in mast cells and other types of cells.

Radioligand binding (Pollard et al., 1993; Medhurst et al., 2008), immunohistochemistry (Chazot et al., 2001), and in situ hybridization studies show the existence of H3Rs throughout the CNS (Pillot et al., 2002). The highest densities of binding sites were seen in the striatum, cerebral cortex, and olfactory tubercles. Moderate levels of H3R mRNA were seen in the periaqueductal gray (PAG), a pivotal region for the supraspinal control of nociceptive transmission.

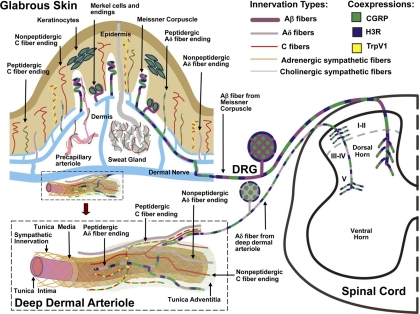

Early measurements of inflammatory peptide release suggested that H3Rs are present on sensory nerves (Delaunois et al., 1995; Ohkubo et al., 1995; Imamura et al., 1996; Rouleau et al., 1997; Poveda et al., 2006), but the localization of H3Rs within the peripheral nervous system and spinal cord (Pollard et al., 1993; Héron et al., 2001; Medhurst et al., 2008) was only recently confirmed by immunohistochemistry (Cannon et al., 2007a). In rat and mouse skin, H3R-like immunoreactivity (H3RLI) was absent in all of the thin-caliber epidermal and superficial dermal innervation, but present in a subset of thin-caliber fibers associated with arterioles in the deep dermis (Fig. 1). By both anatomical location and immunochemical properties, these fibers were classified as peptidergic (i.e., containing both substance P and CGRP), Aδ-like sensory fibers (Fundin et al., 1997; Cannon et al., 2007a; Bowsher et al., 2009). H3KO mice showed a complete loss of the H3RLI on this innervation, confirming the presence of neuronal H3Rs in the deep dermis of normal mice. The perivascular localization of these fibers is consistent with well known functional and anatomical associations between histamine-containing mast cells, blood vessels, and peptidergic afferent fibers (Imamura et al., 1996; Dimitriadou et al., 1997). H3RLI was found on Aβ fibers that terminate in Meissner's corpuscles in glabrous skin and as lanceolate endings in hairy skin, as well as on epidermal keratinocytes and Merkel cells (Cannon et al., 2007a), all of which coexpress CGRP immunoreactivity (Paré et al., 2001; Khodorova et al., 2003) (Fig. 1). The presence of H3RLI (Cannon et al., 2007a) in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and the spinal dorsal horn is consistent with an H3 localization on Aδ and Aβ sensory fibers (see also Medhurst et al., 2008). Although the ability of H3 agonists to reduce peptide release from the skin and elsewhere has been clearly established, the proposed existence of these receptors on sensory C fibers or sympathetic terminals was not confirmed in studies of the skin (Cannon et al., 2007a).

Fig. 1.

Schematic localization of H3Rs in the rat glabrous skin, DRG, and spinal cord. The innervation of glabrous skin is shown (top left), along with an enlargement of a deep dermal arteriole (bottom lower left). Terminations of H3R-expressing Aβ and Aδ innervation are shown in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord (right). Large-caliber (Aβ) and small-caliber (Aδ) myelinated fibers express 200-kDa neurofilament (purple). Smaller-caliber C fibers (red) lack neurofilament. CGRP (green) is expressed in certain types of C fibers, Aδ fibers, and keratinocytes. TrpV1 channels (yellow) are shown on certain CGRP-containing C fibers. Noradrenergic sympathetic fibers (orange) and cholinergic sympathetic fibers (gray) supply blood vessels and sweat glands, respectively. H3Rs (blue) are coexpressed with CGRP on Meissner Aβ fibers, Merkel cells, and keratinocytes (Cannon et al., 2007a). Although these components may be related to pain, the distribution of H3Rs on classically defined pain fibers is limited to the deep dermal perivascular Aδ fibers, which are closely associated with blood vessels. In the skin, activation of H3Rs on peptidergic Aδ fibers presumably suppresses neuropeptide release and attenuates inflammation-related edema (Ohkubo et al., 1995). In the spinal cord, activation of H3Rs reduces nociceptive responses elicited by low-intensity mechanical stimulation (Cannon et al., 2003) and proinflammatory agents such as formalin (Cannon et al., 2007b). Inhibition of transmitter release at the spinal terminations of these deep dermal fibers has been proposed to account for this antinociceptive activity. Although the figure is based on immunohistochemical studies of the skin, DRG, and spinal cord, H3R activation is known to reduce inflammatory peptide release the heart (Imamura et al., 1996), lung (Delaunois et al., 1995), and dura mater (Dimitriadou et al., 1997). Other spinal nerve terminals and spinal neurons may also have H3Rs.

Given that neuronal H3Rs are found in skin, DRG, spinal dorsal horn, and brain, it is not surprising that confusing (even apparently contradictory) results have been reported with H3R-acting drugs in pain assays. The potential for multiple sites of action is enhanced when brain- penetrating and spinally penetrating drugs are administered systemically. This complexity can be reduced by local, intrathecal, or intracerebral drug administration.

Formalin-Induced Nociception

Injection of dilute formalin into the rodent footpad elicits nociceptive motor responses and other signs of inflammation. The former include paw shaking (“flinching”), paw licking, and vocalization. Measurements of any of three end points reveal two well recognized phases of formalin action: “early-phase” responses (0–10 min) are thought to result from direct nociceptor activation; “late-phase” responses (e.g., 15–60 min) follow a brief quiescent period and are considered to be reflective of spinal sensitization mechanisms (Abbott et al., 1995). The ability of H3 agonists to reduce inflammatory peptide release prompted the development of (R)-(−)-2-[[N-[1-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)-2-propyl]imino]phenylmethyl] phenol (BP 2-94) (an H3 agonist prodrug) as a possible analgesic or anti-inflammatory agent (Rouleau et al., 1997). In mice, oral BP 2-94 reduced both phases of formalin-induced licking and biting, but did not modify thermal (hot plate) responses (Rouleau et al., 1997). In a more recent rat study, systemic (subcutaneous) administration of the H3 agonist immepip produced dose-dependent reductions (up to 70%) in both phases of formalin-induced flinching (Cannon et al., 2007b). These effects were mimicked by intrathecal immepip and blocked by systemic and intrathecal thioperamide. Although subcutaneous immepip reduced formalin-induced flinching, this treatment had no effect on formalin-induced vocalizations in rats (Cannon et al., 2007b). Thus, studies in mice and rats with two different H3 agonists (Rouleau et al., 1997; Cannon et al., 2007b) suggest that inhibition of formalin flinching or licking is mediated by activation of spinal H3Rs on peptidergic afferent fibers. If this is correct, then the absence of H3Rs on C fibers in the skin (Fig. 1) and on small DRG neurons (Cannon et al., 2007a) seems to challenge the commonly held view that C-fiber activation evokes formalin-induced flinching (Cannon et al., 2007b). Instead, H3-containing peptidergic Aδ fibers (Cannon et al., 2007a) may be the critical elements for provoking this behavior (Cannon et al., 2007a,b). Alternatively, C-fiber involvement in formalin-induced flinching could involve an indirect mechanism initiated through keratinocyte activation (Dussor et al., 2009). The inhibitory effects of H3 agonists on formalin-induced responses need to studied in H3KO mice to positively confirm the proposed role for spinal H3Rs.

In contrast to the above-cited results with BP 2-94 and immepip, another study reported that systemic administration of the H3 agonist imetit enhanced formalin-induced vocalization responses (Farzin and Nosrati, 2007). These apparently contradictory findings could be caused by the use of vocalization (versus flinching, biting, or licking) as the nociceptive-dependent variable, but other explanations are also possible. Although formalin studies in mice often rely on vocalization responses, there is evidence that different underlying mechanisms may account for supraspinally organized versus spinally organized responses to formalin (Sawynok and Liu, 2004). Additional experiments using multiple routes of injection and measuring both motor and vocalization responses to formalin in wild-type and H3KO mice are needed.

Studies with H3 inverse agonists on formalin nociception have introduced additional complexities. In rats, a moderate dose of thioperamide given alone (15 mg/kg i.p.) had no effect on either phase of formalin-induced flinching; this dose blocked immepip's antiflinching activity (Cannon et al., 2007b). However, a more recent study in rats reported dose-dependent reductions in late-phase, formalin-induced flinching responses after systemic administration of the highly selective, potent H3 inverse agonist 6-[(3-cyclobutyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepin-7-yl)oxy]-N-methyl-3-pyridinecarboxamide (GSK189254) (Hsieh et al., 2010b). Although a spinal action was not shown for this antiformalin effect, other findings in the same article suggest that blockade of spinal H3Rs may produce antinociception by enhancing the release of spinal norepinephrine (Hsieh et al., 2010b). Along the same lines, systemic thioperamide (10–15 mg/kg) antagonized both phases of formalin-induced vocalizations in mice (Farzin and Nosrati, 2007). None of the published findings on formalin nociception by H3R drugs have been validated with H3KO mice.

The idea that both H3 agonists and H3 inverse agonists could have antinociceptive properties in the spinal cord is counterintuitive and requires considerable additional studies. If, as the literature suggests, H3Rs in the spinal cord have multiple locations [e.g., on primary afferent terminals (Cannon et al., 2007a) and spinal noradrenergic terminals (Celuch, 1995)], then there may be an anatomical basis for such effects. It should also be noted that H3 agonists suppressed both early- and late-phase formalin responses (Rouleau et al., 1997; Cannon et al., 2007b), whereas the H3 inverse agonist GSK189254 acted only on the late phase (Hsieh et al., 2010b). The late phase of formalin responding is thought to represent central spinal sensitization. It is also possible that constitutively active H3Rs within the spinal cord might be relevant in understanding these drug actions, because the activity of inverse agonists can depend on the degree of constitutive receptor activity. Although there is compelling evidence that H3Rs in the brain are constitutively active in vivo (Morisset et al., 2000), no such studies have been performed in the spinal cord.

Peripheral H3Rs and Inflammation

Many studies have reported that H3R activation inhibits peptide release (CGRP and substance P) from sensory nerves in skin and other organs. Such effects are thought to account for the well established anti-inflammatory properties of systemically and locally administered H3 agonists. Active compounds include BP 2-94 (Rouleau et al., 1997, 2000), RAMH (Ohkubo et al., 1995; Dimitriadou et al., 1997; Poveda et al., 2006), imetit (Delaunois et al., 1995; Imamura et al., 1996), and immepip (Cannon et al., 2007b). Inflammation provoked by many treatments (including antidromic nerve stimulation, formalin, capsaicin, zymosan, complete Freud's adjuvant, and bradykinin) is reduced by these drugs; end points measured include edema, plasma extravasation, and increases in vascular permeability. Local application of the agonists to heart (Imamura et al., 1996), lung (Delaunois et al., 1995), and dura mater (Dimitriadou et al., 1997) effectively reduced these inflammatory responses, strongly suggesting that H3Rs on local afferent fibers can attenuate peptide-mediated inflammation. The H4 agonist properties of immepip and imetit (Lim et al., 2005) may or may not be relevant for inflammation research. H4 antagonists have potent anti-inflammatory activity (Hsieh et al., 2010a), but assessment of anti-inflammatory actions of H4 agonists has not been published. The target for the anti-inflammatory effects of H3 agonists has not been confirmed with H3KO mice experiments.

Studies of drug dose and route show the necessity of considering separately the anti-inflammatory versus antinociceptive properties of H3 agonists. For example, in formalin-treated rats, systemically administered immepip reduced both nociceptive flinching and paw edema, but intrathecally delivered immepip reduced the former, but not the latter (Cannon et al., 2007b). Thus, systemically administered H3 agonists seem to act directly on peripheral fibers in the skin to reduce peptide-mediated inflammation (Cannon et al., 2007b). Combinations of intradermal injections of formalin and H3 agonists have not directly tested this hypothesis.

Acute Mechanical Nociception: Relevance of Dermal and Spinal H3Rs

Spinal H3Rs seem to be capable of attenuating specific types of acute nociceptive transmission. In rats, systemically administered immepip produced dose-dependent decreases in nociceptive responses to low-intensity mechanical tail pinch, but had no effect on thermally evoked (i.e., tail-flick and hot plate) responses; the effect was mimicked by two different intrathecally administered H3 agonists and blocked by intrathecally injected thioperamide (Cannon et al., 2003). In mice, immepip effectively attenuated mechanical nociception after intrathecal, but not subcutaneous, administration (Cannon et al., 2003). Because systemically administered immepip was effective against mechanical nociception in rats, Cannon et al. (2003) suggested the possibility of a species difference in the spinal penetration by immepip, but several explanations seem possible for the discrepancy. A subsequent detailed evaluation with a wide variety of nociceptive stimuli in rats confirmed that the acute antinociceptive profile of H3 agonists is both modality-specific (i.e., mechanical versus thermal) and intensity-specific (low versus high mechanical) (Cannon and Hough, 2005). Collectively, the studies show that low-intensity mechanical nociception is attenuated by activation of spinal H3Rs (Cannon et al., 2003; Cannon and Hough, 2005). Because 1) specific types of H3R-containing peripheral afferent fibers project to the dorsal horn, and 2) dorsal horn neurons have limited expression of H3R message (Héron et al., 2001) and H3RLI (Cannon et al., 2007a), it was suggested that the antinociceptive effects of intrathecal H3 agonists are mediated by inhibition of transmitter release from afferent fibers in the spinal cord, a presynaptic effect (Cannon et al., 2003). Whereas such a presynaptic H3 action may explain the attenuation of mechanical nociception, newer findings suggest that H3Rs elsewhere in the spinal cord may also have pain-related functions (see below).

The mechanical antinociceptive effects of intrathecally delivered H3 agonists in rats and mice, and the attenuation of these effects with the H3 inverse agonist thioperamide, suggest that spinal H3 receptors are the targets for these drugs (Cannon et al., 2003). Although immepip and thioperamide have H4 and H3 affinity, the intrathecal effects of immepip on mechanical nociception were completely abolished in H3KO mice, confirming the significance of the proposed target receptor (Cannon et al., 2003). Based on a review of current literature, the mechanical antinociceptive properties of intrathecal immepip are the only H3R-related pain results to have been validated with knockout mice studies.

If activation of spinal H3Rs produces mechanical antinociception, then H3 antagonists or H3 inverse agonists might be expected to produce the opposite (hyperalgesic) effect. However, this would occur only if the spinal presynaptic H3Rs were normally active. H3 blockade with thioperamide in rats (10 mg/kg s.c., a dose that blocked the intrathecal effects of immepip) had no effect on baseline mechanical nociception when given alone (Cannon et al., 2003), implying that H3Rs are not active during acute mechanical nociception. Also consistent with this conclusion, H3KO mice have normal baseline responses to mechanical pinch (Cannon et al., 2003). In a separate study, a larger dose of thioperamide given alone (20 mg/kg i.p.) produced antinociception on the paw pressure test (Malmberg-Aiello et al., 1994). A thioperamide action on brain (versus spinal) H3Rs may account for this effect, consistent with the mechanical hyperalgesic actions of brain-administered RAMH in the same study (Malmberg-Aiello et al., 1994).

The discovery of H3Rs on peptidergic, periarteriolar Aδ fibers in the deep dermis led to the suggestion that these fibers might mediate high-threshold mechanical nociception (Cannon et al., 2007a). Although not proven, the hypothesis has support from several findings: 1) H3KO mice lack H3RLI in the deep dermis, DRG, and spinal cord (Cannon et al., 2007a); 2) intrathecal immepip reduces mechanical nociception in control, but not in H3KO, mice (Cannon et al., 2003); and 3) the H3R-containing Aδ fibers in the deep dermis possess ASIC3 channels (Molliver et al., 2005), which may be transducers of mechanical nociception (Hu et al., 2006). Although the epidermis is widely held to be responsible for touch and pain perception from the skin, a study has reported that patients with a total loss of epidermal innervation could still detect cutaneous stimulation (Bowsher et al., 2009). A sensory transduction role for dermal vascular afferents is consistent with these provocative new findings.

Although intrathecal H3 agonists suppress acute mechanical nociception in healthy subjects, the relevance of this finding for clinical pain is unknown. The effects of intrathecal H3 agonists in chronic pain models (including mechanical allodynia after nerve injury) have not been reported. The possibility that deep dermal pain (such as seen in fibromyalgia) might be attenuated by systemic or spinally administered H3 agonists has not been investigated. Systemically administered H3 agonists achieve some degree of brain and spinal penetration. In rats, spinal penetration by immepip is sufficient to suppress mechanical nociception (Cannon et al., 2003); very modest doses decrease hypothalamic histamine release (Jansen et al., 1998).

Antinociceptive Profile for Brain Histamine

Histamine, a pain-enhancing substance in the skin and spinal cord (Kajihara et al., 2010), reduces nociceptive transmission when injected directly into the brain (Glick and Crane, 1978; Chung et al., 1984; Bhattacharya and Parmar, 1985; Braga et al., 1992; Sibilia et al., 1992; Malmberg-Aiello et al., 1994; Thoburn et al., 1994). H1 and H2 receptors are thought to mediate this effect (Thoburn et al., 1994; Braga et al., 1996; Lamberti et al., 1996). Related to pain relief, H2 receptors in the brain are activated as part of opioid and nonopioid antinociceptive mechanisms (Gogas and Hough, 1989; Gogas et al., 1989), especially when stress elicits or enhances these responses (Nalwalk and Hough, 1995). Such findings suggest that treatments that enhance neuronal histamine release (e.g., blockade of brain H3 autoreceptors) should relieve pain. There is also evidence that exposure to nociceptive stimuli increases neuronal histamine turnover (Itoh et al., 1989). As discussed below, drugs that reduce H3 activity (inverse agonists and/or antagonists) act in the brain or spinal cord to modify nociceptive thresholds in several acute and chronic pain tests.

Bidirectional Modulation of Acute Thermal Nociceptive Responses

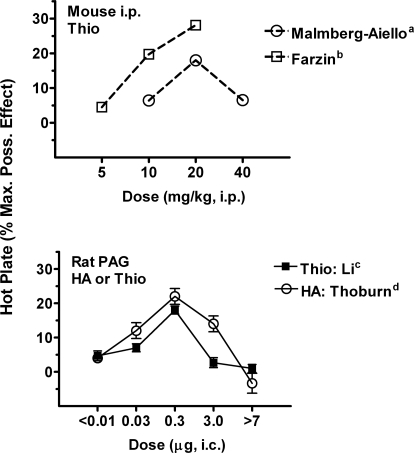

Several laboratory groups have shown that thioperamide inhibits hot-plate nociceptive responses in rodents. In mice, low systemic doses (1–5 mg/kg) are inactive (Owen et al., 1994; Suzuki et al., 1994), but higher doses (5–30 mg/kg) produce dose-dependent, mild antinociceptive effects (Malmberg-Aiello et al., 1994; Farzin et al., 2002). These treatments do not impair motor balance in the rotorod test, suggesting a pain-relieving profile (Farzin et al., 2002). Intraventricular (Oluyomi and Hart, 1991), but not intrathecal (Suh et al., 1999; Mobarakeh et al., 2009), injections of thioperamide reproduce these antinociceptive effects on the hot-plate test, implying that the systemically administered drug targets brain H3Rs. Although intrathecal thioperamide is inactive on acute thermal tests when given alone, it is interesting that this treatment can either enhance (Mobarakeh et al., 2009) or inhibit (Suh et al., 1999) opioid antinociceptive responses in these tests, depending on whether the opioid is given intrathecally (Mobarakeh et al., 2009) or supraspinally (Suh et al., 1999), respectively. In rats, intracerebral injections of thioperamide into the PAG reproduce the mild antinociceptive effects seen after systemic and intraventricular thioperamide (Li et al., 1996; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Biphasic modulation of acute nociceptive responses by thioperamide (Thio) and histamine (HA). Data from published studies show dose-response curves for Thio and HA in mice (top) and rats (bottom) on the hot-plate test. Antinociceptive scores (ordinate, maximal possible effect; see Li et al., 1996) range from 0 to 100%. Thio was administered by systemic (intraperitoneal; top) or intracerebral injections into the PAG (bottom). The figure shows that: 1) the biphasic actions of systemically injected Thio can be replicated by microinjections of the same drug into the PAG, and 2) intracerebral HA injections in the PAG can closely mimic the effects of Thio, consistent with the known HA-releasing properties of this H3 inverse agonist. Data are plotted: a, 15 min after Thio (Malmberg-Aiello et al., 1994); b, 40 min after Thio (Farzin et al., 2002); c, 10 min after intra-PAG Thio (Li et al., 1996); d, 5 min after intra-PAG HA (Thoburn et al., 1994).

Many brain-acting analgesics produce dose-dependent 100% antinociception on thermal tests, but thioperamide's maximal activity on the rat hot-plate test is only approximately 30% of maximal responses (Fig. 2). Dose-response studies with thioperamide (given systemically, or by microinjection into the PAG) found biphasic activity (Fig. 2), with doses greater than those eliciting a 30% response producing less antinociception. Thioperamide is known to increase the release of neuronal histamine in the rat PAG (Barke and Hough, 1994), and histamine microinjections into the PAG produce biphasic antinociceptive activity that is remarkably similar to that produced by systemic or intracerebrally administered thioperamide (Fig. 2). Thus, in acute thermal nociceptive tests, thioperamide seems to reproduce both the pain-relieving and pain-enhancing actions of neuronal histamine in the PAG. Descending brainstem circuits are known to exert bidirectional control over spinal nociception (Heinricher and Ingram, 2008), and the biphasic actions of thioperamide and histamine (Fig. 2) may be indicative of separate activation of pain-inhibiting and pain-enhancing circuits. The target for thioperamide's effects in these studies is likely to be the brain H3R but pharmacological studies are limited. For example, centrally (Oluyomi and Hart, 1991) and systemically (Malmberg-Aiello et al., 1994) administered H3 agonists have pronociceptive actions on the hot-plate test. As noted above, the H4 activity of thioperamide shows the need for confirmatory studies in H3KO mice and additional testing with more H3R-selective compounds.

H3Rs in Models of Chronic Pain

Many analgesics that are effective in animals and humans work extremely well in acute thermal and mechanical nociceptive tests, but these tests are not models of clinical pain. Clinically relevant human pain is usually chronic and can result from a variety of inflammatory, immunological, or tissue-injuring conditions (Argoff et al., 2009). Of special interest is neuropathic pain, in which acute nerve injury produces chronic, exaggerated, and often debilitating pain. Neuropathic pain is highly prevalent and difficult to treat (Campbell and Meyer, 2006; Dray, 2008; Argoff et al., 2009). In an attempt to model more closely these characteristics of clinical pain, several experimental pain tests in animals measure hyperalgesia (exaggerated response to a painful stimuli) and/or allodynia (nociceptive response to a nonpainful stimulus) after tissue damage, nerve injury, or inflammation. The popularity of these tests has produced an explosion of new information on biological and biochemical mediators of neuropathic pain (Jarvis and Boyce-Rustay, 2009; Milligan and Watkins, 2009). As detailed below, H3 antagonists/inverse agonists have been evaluated in some of these models. It should also be noted that studies of human skin of patients with complex regional pain syndrome type 1 and postherpetic neuralgia and studies of rhesus monkeys with type 2 diabetes have revealed significant structural and chemical pathologies among the various components of the skin that normally express H3Rs in rats and mice. These include not only perivascular Aδ fibers, but also epidermal keratinocytes, Aβ fiber Meissner's corpuscle endings, and lanceolate endings (Petersen et al., 2002; Albrecht et al., 2006; Cannon et al., 2007a; Paré et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008).

Results with thioperamide suggest the possibility that both peripheral and brain H3Rs can modulate neuropathic pain. Mechanical allodynia was enhanced by a small, systemic dose of thioperamide (3.6 mg/kg i.p.) in rats subjected to partial ligation of the sciatic nerve (Huang et al., 2007). In a related pain model, injection of thioperamide (60 μg) into the injured hind paw had a similar effect (Smith et al., 2007). Experiments with H4 agonists and antagonists suggest the possibility that the local thioperamide effect could be mediated through an H4 (versus H3) action (Smith et al., 2007). A large intraventricular dose of thioperamide (30 μg) had the opposite (antiallodynic) effect in the sciatic nerve ligation model, implying opposing roles for peripheral and central H3Rs (Huang et al., 2007).

Dramatic progress has been reported in developing potent, highly selective H3 inverse agonists that lack H4 affinity and have good brain-penetrating properties (Leurs et al., 2005; Esbenshade et al., 2006; Sander et al., 2008; Gemkow et al., 2009). Because many of these drugs are new, however, their pain-relieving properties have not been fully evaluated. Two new orally active H3 inverse agonists had no activity on mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds in normal rats, but inhibited capsaicin-induced mechanical allodynia by 20 to 65% over a range of doses (Medhurst et al., 2007). In a follow-up study (Medhurst et al., 2008), chronic oral dosing (5–8 days) with brain-penetrating H3 inverse agonists reversed mechanical hyperalgesia in the chronic constriction injury model. The effects were not complete, and not dose-dependent, but were comparable with those of a clinically effective, positive control (gabapentin). Two of the compounds also effectively reversed varicella zoster viral-induced mechanical allodynia in rats (Medhurst et al., 2008). These experiments used multiple measures of allodynia and demonstrated oral bioavailability, adequate brain penetration, and efficacy with chronic dosing comparable with gabapentin, but it is puzzling that the antiallodynic effects were not consistently produced by single doses of the H3 inverse agonist drugs.

Another group has confirmed the efficacy of H3 inverse agonists in several chronic pain tests (Hsieh et al., 2010b). Single systemic injections of GSK189254 produced dose-dependent (up to a 70%) reversal of mechanical allodynia induced by spinal nerve ligation. These effects, shown to be similar to those of gabapentin, strongly resemble those seen in the chronic constriction and viral neuropathy models discussed above (Medhurst et al., 2008). In the same study (Hsieh et al., 2010b), GSK189254 also prevented tactile allodynia after treatment with complete Freud's adjuvant, but had no effect on carrageenan-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Although these exciting new results suggest that H3R inverse agonists could be useful in neuropathic and/or inflammatory pain, additional studies with microinjections and knockout animals are needed to establish the sites of action and confirm the identity of the drugs' target.

Selective H3 inverse agonists are also active in other pain assays. In the monoiodoacetate arthritis model, four different drugs produced dose-dependent antinociception (Hsieh et al., 2010b). Maximal effects were 53 to 74% reversal of impairment, and none of these drugs affected grip force in the absence of the experimental arthritis. One H3 inverse agonist (GSK189254) was also active in the arthritis model after intrathecal administration, showing the spinal cord to be an important site of action. Both the systemic and intrathecal antiarthritis effects of GSK189254 were reversed by pretreatment with the α2 adrenergic antagonist phentolamine (Hsieh et al., 2010b), suggesting a critical role for spinal noradrenergic mechanisms in the antinociceptive effect. Supraspinally acting analgesics are known to activate spinal α2-mediated analgesic mechanisms (Millan, 2002), but stimulation of this mechanism by an action on spinal H3Rs is novel and potentially very important.

These recent studies with new H3R inverse agonists suggest that these compounds could be effective in treating neuropathic, inflammatory, or arthritis pain, but additional basic and clinical studies are needed. The anticipated approval of these drugs for several nonpain indications in humans (Gemkow et al., 2009; Tiligada et al., 2009) may permit evaluation of their potential as pain medicines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Julia Nalwalk for assistance with figures and excellent proofreading.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse [Grants DA-03816, DA-027835].

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.110.171264.

- H3R

- H3 receptor

- H3RLI

- H3R-like immunoreactivity

- H3KO

- H3R knockout

- DRG

- dorsal root ganglia

- PAG

- periaqueductal gray

- RAMH

- R-α-methylhistamine

- CGRP

- calcitonin gene-related peptide

- CNS

- central nervous system

- BP 2-94

- (R)-(−)-2-[[N-[1-(1H-imidazol-4-yl)-2-propyl]imino]phenylmethyl] phenol

- GSK189254

- 6-[(3-cyclobutyl-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H-3-benzazepin-7-yl)oxy]-N-methyl-3-pyridinecarboxamide

- Thio

- thioperamide

- HA

- histamine.

Authorship Contributions

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Hough and Rice.

References

- Abbott FV, Franklin KB, Westbrook RF. (1995) The formalin test: scoring properties of the first and second phases of the pain response in rats. Pain 60:91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht PJ, Hines S, Eisenberg E, Pud D, Finlay DR, Connolly MK, Paré M, Davar G, Rice FL. (2006) Pathologic alterations of cutaneous innervation and vasculature in affected limbs from patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Pain 120:244–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argoff CE, Albrecht P, Irving G, Rice F. (2009) Multimodal analgesia for chronic pain: rationale and future directions. Pain Med 10 (Suppl 2):S53–S66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Lancelot JC, Lecomte JM, Pollard H, Robba M, Schunack W, Schwartz JC. (1987) Highly potent and selective ligands for histamine H3-receptors. Nature 327:117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barke KE, Hough LB. (1994) Characterization of basal and morphine-induced histamine release in the rat periaqueductal gray. J Neurochem 63:238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson JM, Chaouch A. (1987) Peripheral and spinal mechanisms of nociception. Physiol Rev 67:67–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya SK, Parmar SS. (1985) Antinociceptive effect of intracerebroventricularly administered histamine in rats. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol 49:125–136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongers G, Bakker RA, Leurs R. (2007) Molecular aspects of the histamine H3 receptor. Biochem Pharmacol 73:1195–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowsher D, Geoffrey Woods C, Nicholas AK, Carvalho OM, Haggett CE, Tedman B, Mackenzie JM, Crooks D, Mahmood N, Twomey JA, et al. (2009) Absence of pain with hyperhidrosis: a new syndrome where vascular afferents may mediate cutaneous sensation. Pain 147:287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga PC, Sibilia V, Guidobono E, Pecile A, Netti C. (1992) Electrophysiological correlates for antinociceptive effects of histamine after intracerebral administration to the rat. Neuropharmacology 31:937–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braga PC, Soldavini E, Pecile A, Sibilia V, Netti C. (1996) Involvement of H1 receptors in the central antinociceptive effect of histamine: pharmacological dissection by electrophysiological analysis. Experientia 52:60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JN, Meyer RA. (2006) Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron 52: 77–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon KE, Hough LB. (2005) Inhibition of chemical and low-intensity mechanical nociception by activation of histamine H3 receptors. J Pain 6:193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon KE, Chazot PL, Hann V, Shenton F, Hough LB, Rice FL. (2007a) Immunohistochemical localization of histamine H3 receptors in rodent skin, dorsal root ganglia, superior cervical ganglia, and spinal cord: potential antinociceptive targets. Pain 129:76–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon KE, Leurs R, Hough LB. (2007b) Activation of peripheral and spinal histamine H3 receptors inhibits formalin-induced inflammation and nociception, respectively. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 88:122–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon KE, Nalwalk JW, Stadel R, Ge P, Lawson D, Silos-Santiago I, Hough LB. (2003) Activation of spinal histamine H3 receptors inhibits mechanical nociception. Eur J Pharmacol 470:139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celuch SM. (1995) Possible participation of histamine H3 receptors in the modulation of noradrenaline release from rat spinal cord slices. Eur J Pharmacol 287:127–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazot PL, Hann V, Wilson C, Lees G, Thompson CL. (2001) Immunological identification of the mammalian H3 histamine receptor in the mouse brain. NeuroReport 12:259–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YH, Miyake H, Kamei C, Tasaka K. (1984) Analgesic effect of histamine induced by intracerebral injection into mice. Agents Actions 15:137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connelly WM, Shenton FC, Lethbridge N, Leurs R, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Lees G, Chazot PL. (2009) The histamine H4 receptor is functionally expressed on neurons in the mammalian CNS. Br J Pharmacol 157:55–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Esch IJ, Leurs R, Timmerman H. (2009) Histamine receptors, in Textbook of Drug Design and Discovery (Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Madsen U, Stromgaard K. eds) pp. 283–297, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- Delaunois A, Gustin P, Garbarg M, Ansay M. (1995) Modulation of acetylcholine, capsaicin and substance P effects by histamine H3 receptors in isolated perfused rabbit lungs. Eur J Pharmacol 277:243–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadou V, Rouleau A, Trung Tuong MD, Newlands GJ, Miller HR, Luffau G, Schwartz JC, Garbarg M. (1997) Functional relationships between sensory nerve fibers and mast cells of dura mater in normal and inflammatory conditions. Neuroscience 77:829–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dray A. (2008) Neuropathic pain: emerging treatments. Br J Anaesth 101:48–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dussor G, Koerber HR, Oaklander AL, Rice FL, Molliver DC. (2009) Nucleotide signaling and cutaneous mechanisms of pain transduction. Brain Res Rev 60:24–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbenshade TA, Fox GB, Cowart MD. (2006) Histamine H3 receptor antagonists: preclinical promise for treating obesity and cognitive disorders. Mol Interv 6:77–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin D, Nosrati F. (2007) Modification of formalin-induced nociception by different histamine receptor agonists and antagonists. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 17:122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzin D, Asghari L, Nowrouzi M. (2002) Rodent antinociception following acute treatment with different histamine receptor agonists and antagonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 72:751–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fundin BT, Pfaller K, Rice FL. (1997) Different distributions of the sensory and autonomic innervation among the microvasculature of the rat mystacial pad. J Comp Neurol 389:545–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemkow MJ, Davenport AJ, Harich S, Ellenbroek BA, Cesura A, Hallett D. (2009) The histamine H3 receptor as a therapeutic drug target for CNS disorders. Drug Discov Today 14:509–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SD, Crane LA. (1978) Opiate-like and abstinence-like effects of intracerebral histamine administration in rats. Nature 273:547–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogas KR, Hough LB. (1989) Inhibition of naloxone- resistant antinociception by centrally administered H2 antagonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 248:262–267 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogas KR, Hough LB, Eberle NB, Lyon RA, Glick SD, Ward SJ, Young RC, Parsons ME. (1989) A role for histamine and H2-receptors in opioid antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 250:476–484 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas H, Panula P. (2003) The role of histamine and the tuberomamillary nucleus in the nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci 4:121–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinricher MM, Ingram SL. (2008) The brainstem and nociceptive modulation, in The Senses: A Comprehensive Reference. Volume 5: Pain (Basbaum AI, Bushnell MC, Julius D. eds) pp 593–626, Elsevier, New York [Google Scholar]

- Héron A, Rouleau A, Cochois V, Pillot C, Schwartz JC, Arrang JM. (2001) Expression analysis of the histamine H(3) receptor in developing rat tissues. Mech Dev 105:167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough LB. (2001) Genomics meets histamine receptors: new subtypes, new receptors. Mol Pharmacol 59:415–419 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough LB, Leurs R. (2006) Histamine, in Basic Neurochemistry, 7th ed (Siegel G, Agranoff B, Albers R, Fisher S, Uhler M.eds) pp 249–266, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh GC, Chandran P, Salyers AK, Pai M, Zhu CZ, Wensink EJ, Witte DG, Miller TR, Mikusa JP, Baker SJ, et al. (2010a) H4 receptor antagonism exhibits anti-nociceptive effects in inflammatory and neuropathic pain models in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 95:41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh GC, Honore P, Pai M, Wensink EJ, Chandran P, Salyers AK, Wetter JM, Zhao C, Liu H, Decker MW, et al. (2010b) Antinociceptive effects of histamine H3 receptor antagonist in the preclinical models of pain in rats and the involvement of central noradrenergic systems. Brain Res 1354:74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Milenkovic N, Lewin GR. (2006) The high threshold mechanotransducer: a status report. Pain 120:3–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Adachi N, Nagaro T, Liu K, Arai T. (2007) Histaminergic involvement in neuropathic pain produced by partial ligation of the sciatic nerve in rats. Reg Anesth Pain Med 32:124–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura M, Smith NC, Garbarg M, Levi R. (1996) Histamine H3-receptor-mediated inhibition of calcitonin gene-related peptide release from cardiac C fibers. A regulatory negative-feedback loop. Circ Res 78:863–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Oishi R, Nishibori M, Saeki K. (1989) Effects of nociceptive stimuli on brain histamine dynamics. Jap J Pharmacol 49:449–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen FP, Mochizuki T, Yamamoto Y, Timmerman H, Yamatodani A. (1998) In vivo modulation of rat hypothalamic histamine release by the histamine H3 receptor ligands, immepip and clobenpropit. Effects of intrahypothalamic and peripheral application. Eur J Pharmacol 362:149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MF, Boyce-Rustay JM. (2009) Neuropathic pain: models and mechanisms. Curr Pharm Des 15:1711–1716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajihara Y, Murakami M, Imagawa T, Otsuguro K, Ito S, Ohta T. (2010) Histamine potentiates acid-induced responses mediating transient receptor potential V1 in mouse primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience 166:292–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodorova A, Navarro B, Jouaville LS, Murphy JE, Rice FL, Mazurkiewicz JE, Long-Woodward D, Stoffel M, Strichartz GR, Yukhananov R, et al. (2003) Endothelin-B receptor activation triggers an endogenous analgesic cascade at sites of peripheral injury. Nat Med 9:1055–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti C, Bartolini A, Ghelardini C, Malmberg-Aiello P. (1996) Investigation into the role of histamine receptors in rodent antinociception. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 53:567–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bars D, Gozariu M, Cadden SW. (2001) Animal models of nociception. Pharmacol Rev 53:597–652 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leurs R, Bakker RA, Timmerman H, de Esch IJ. (2005) The histamine H3 receptor: from gene cloning to H3 receptor drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4:107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li BY, Nalwalk JW, Barker LA, Cumming P, Parsons ME, Hough LB. (1996) Characterization of the antinociceptive properties of cimetidine and a structural analog. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 276:500–508 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HD, van Rijn RM, Ling P, Bakker RA, Thurmond RL, Leurs R. (2005) Evaluation of histamine H1-, H2-, and H3-receptor ligands at the human histamine H4 receptor: identification of 4-methylhistamine as the first potent and selective H4 receptor agonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 314:1310–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg-Aiello P, Lamberti C, Ghelardini C, Giotti A, Bartolini A. (1994) Role of histamine in rodent antinociception. Br J Pharmacol 111:1269–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst AD, Briggs MA, Bruton G, Calver AR, Chessell I, Crook B, Davis JB, Davis RP, Foley AG, Heslop T, et al. (2007) Structurally novel histamine H3 receptor antagonists GSK207040 and GSK334429 improve scopolamine-induced memory impairment and capsaicin-induced secondary allodynia in rats. Biochem Pharmacol 73:1182–1194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst SJ, Collins SD, Billinton A, Bingham S, Dalziel RG, Brass A, Roberts JC, Medhurst AD, Chessell IP. (2008) Novel histamine H3 receptor antagonists GSK189254 and GSK334429 are efficacious in surgically-induced and virally-induced rat models of neuropathic pain. Pain 138:61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. (2002) Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol 66:355–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan ED, Watkins LR. (2009) Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci 10:23–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobarakeh JI, Takahashi K, Yanai K. (2009) Enhanced morphine-induced antinociception in histamine H3 receptor gene knockout mice. Neuropharmacology 57:409–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molliver DC, Immke DC, Fierro L, Paré M, Rice FL, McCleskey EW. (2005) ASIC3, an acid-sensing ion channel, is expressed in metaboreceptive sensory neurons. Mol Pain 1:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisset S, Rouleau A, Ligneau X, Gbahou F, Tardivel-Lacombe J, Stark H, Schunack W, Ganellin CR, Schwartz JC, Arrang JM. (2000) High constitutive activity of native H3 receptors regulates histamine neurons in brain. Nature 408:860–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalwalk JW, Hough LB. (1995) Importance of histamine H2 receptors in restraint-morphine interactions. Life Sci 57:PL153–PL158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkubo T, Shibata M, Inoue M, Kaya H, Takahashi H. (1995) Regulation of substance P release mediated via prejunctional histamine H3 receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 273:83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluyomi AO, Hart SL. (1991) Involvement of histamine in naloxone-resistant and naloxone-sensitive models of swim stress-induced antinociception in the mouse. Neuropharmacology 30:1021–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen SM, Sturman G, Freeman P. (1994) Modulation of morphine-induced antinociception in mice by histamine H3-receptor ligands. Agents Actions 41:C62–C63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré M, Albrecht PJ, Noto CJ, Bodkin NL, Pittenger GL, Schreyer DJ, Tigno XT, Hansen BC, Rice FL. (2007) Differential hypertrophy and atrophy among all types of cutaneous innervation in the glabrous skin of the monkey hand during aging and naturally occurring type 2 diabetes. J Comp Neurol 501:543–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paré M, Elde R, Mazurkiewicz JE, Smith AM, Rice FL. (2001) The Meissner corpuscle revised: a multiafferented mechanoreceptor with nociceptor immunochemical properties. J Neurosci 21:7236–7246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen KL, Rice FL, Suess F, Berro M, Rowbotham MC. (2002) Relief of post-herpetic neuralgia by surgical removal of painful skin. Pain 98:119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillot C, Heron A, Cochois V, Tardivel-Lacombe J, Ligneau X, Schwartz JC, Arrang JM. (2002) A detailed mapping of the histamine H(3) receptor and its gene transcripts in rat brain. Neuroscience 114:173–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard H, Moreau J, Arrang JM, Schwartz JC. (1993) A detailed autoradiographic mapping of histamine H3 receptors in rat brain areas. Neuroscience 52:169–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poveda R, Fernández-Dueñas V, Fernández A, Sánchez S, Puig MM, Planas E. (2006) Synergistic interaction between fentanyl and the histamine H3 receptor agonist R-(α)-methylhistamine, on the inhibition of nociception and plasma extravasation in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 541:53–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice AS, Cimino-Brown D, Eisenach JC, Kontinen VK, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Machin I. Preclinical Pain Consortium, Mogil JS, Stöhr T. (2008) Animal models and the prediction of efficacy in clinical trials of analgesic drugs: a critical appraisal and call for uniform reporting standards. Pain 139:243–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau A, Garbarg M, Ligneau X, Mantion C, Lavie P, Advenier C, Lecomte JM, Krause M, Stark H, Schunack W, et al. (1997) Bioavailability, antinociceptive and antiinflammatory properties of BP 2-94, a histamine H3 receptor agonist prodrug. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 281:1085–1094 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau A, Stark H, Schunack W, Schwartz JC. (2000) Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive properties of BP 2-94, a histamine H(3)-receptor agonist prodrug. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 295:219–225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander K, Kottke T, Stark H. (2008) Histamine H3 receptor antagonists go to clinics. Biol Pharm Bull 31:2163–2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawynok J, Liu XJ. (2004) The formalin test: characteristics and usefulness of the model. Rev Analg 7:145–163 [Google Scholar]

- Sibilia V, Netti C, Guidobono F, Pecile A, Braga PC. (1992) Central antinociceptive action of histamine: Behavioural and electrophysiological studies. Agents Actions 36(Suppl C):C350–C353 [Google Scholar]

- Smith FM, Haskelberg H, Tracey DJ, Moalem-Taylor G. (2007) Role of histamine H3 and H4 receptors in mechanical hyperalgesia following peripheral nerve injury. Neuroimmunomodulation 14:317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakhova MI, Nikkel AL, Manelli AM, Hsieh GC, Esbenshade TA, Brioni JD, Bitner RS. (2009) Localization of histamine H4 receptors in the central nervous system of human and rat. Brain Res 1250:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh HW, Chung KM, Kim YH, Huh SO, Song DK. (1999) Effects of histamine receptor antagonists injected intrathecally on antinociception induced by opioids administered intracerebroventricularly in the mouse. Neuropeptides 33:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Takamori K, Takahashi Y, Narita M, Misawa M, Onodera K. (1994) The differential effects of histamine receptor antagonists on morphine- and U-50,488H-induced antinociception in the mouse. Life Sci 54:203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoburn KK, Hough LB, Nalwalk JW, Mischler SA. (1994) Histamine-induced modulation of nociceptive responses. Pain 58:29–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiligada E, Zampeli E, Sander K, Stark H. (2009) Histamine H3 and H4 receptors as novel drug targets. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 18:1519–1531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vierck CJ, Hansson PT, Yezierski RP. (2008) Clinical and pre-clinical pain assessment: are we measuring the same thing? Pain 135:7–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollinga RC, de Koning JP, Jansen FP, Leurs R, Menge WM, Timmerman H. (1994) A new potent and selective histamine H3 receptor agonist, 4-(1H-imidazol-4-ylmethyl)piperidine. J Med Chem 37:332–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P, Barr TP, Hou Q, Dib-Hajj SD, Black JA, Albrecht PJ, Petersen K, Eisenberg E, Wymer JP, Rice FL, et al. (2008) Voltage-gated sodium channel expression in rat and human epidermal keratinocytes: evidence for a role in pain. Pain 139:90–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]