Abstract

In this study, a Cu2+ chelate of the novel thiosemicarbazone NSC 689534 was evaluated for in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer activity. Results demonstrated that NSC 689534 activity (low µM range) was enhanced 4–5 fold by copper chelation and completely attenuated by iron. Importantly, once formed, the NSC 689534/Cu2+ complex retained activity in the presence of additional iron or iron-containing biomolecules. NSC 689534/Cu2+ mediated its effects primarily through the induction of ROS, with depletion of cellular glutathione and protein thiols. Pre-treatment of cells with the antioxidant L-NAC impaired activity, whereas NSC 689534/Cu2+ effectively synergized with the glutathione biosynthesis inhibitor, buthionine sulphoximine. Microarray analysis of NSC 689534/Cu2+-treated cells highlighted activation of pathways involved in oxidative and ER-stress/UPR, autophagy and metal metabolism. Further scrutiny of the role of ER-stress and autophagy indicated that NSC 689534/Cu2+ -induced cell death was ER-stress dependent and autophagy-independent. Lastly, NSC 689534/Cu2+ was shown to have activity in an HL60 xenograft model. These data suggest that NSC 689534/Cu2+ is a potent oxidative stress inducer worthy of further preclinical investigation.

Keywords: thiosemicarbazone, copper, ER stress, UPR, macroautophagy, oxidative stress

Introduction

The ability of thiosemicarbazones to form stable complexes with transition metal ions makes them versatile pharmacophores. Indeed, diverse thiosemicarbazones have been explored as antiviral, antifungal, antibacterial and antitumoral agents [1, 2]. Inherent in the design of the thiosemicarbazone is the ability to form metal complexes with transition state metals such as iron, copper and zinc [1]. Metal binding affinity and antitumor activity varies with each individual compound and mechanistic differences have been noted based on whether iron or copper is the preferred chelation partner. Both are redox-active metals with the potential for reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation [2]. Thus, intracellular delivery of redox-active transition metals can be used to alter redox homeostasis for therapeutic benefit [3].

The most comprehensively studied anti-cancer thiosemicarbazone is triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone; 3-AP). As a consequence of high-affinity iron chelation, triapine is a potent inhibitor of iron containing enzymes such as ribonucleotide reductase (RR) and p53R2 [4, 5]. While it was previously thought that the inhibitory activity of 3-AP was due to the direct removal of Fe from the enzymes, recent evidence suggests that redox effects of the 3-AP-Fe complex on these enzymes is also important [6, 7]. The first attempts at clinical evaluation of 3-AP as a single agent or in combination with gemcitabine failed to demonstrate efficacy, however in more recent trials the combination of 3-AP with fludarabine or cytarabine in patients with refractory acute leukemia, aggressive myeloproliferative disorders or myeloid leukemia showed some promise (reviewed in [1]). Preliminary data also suggests that triapine may improve outcomes for patients with advanced stage cervical cancer in combination with radiation and cisplatin [8]. Ten patients (100%) with stage IB2 to IVB cervical cancer achieved complete clinical response and remained disease free for a median of 18 months, providing anecdotal evidence for improved outcomes relative to current treatments.

The antitumor potential of copper-chelated thiosemicarbazones has also been explored. Early studies with copper chelates of the thiosemicarbazones, 2- formylpyridine and 4-formylpyridine, showed that both agents were capable of inducing cell death associated with ROS generation and depletion of cellular glutathione [9, 10]. [64Cu]-conjugated thiosemicarbazones (e.g. Cu-ATSM) are also being developed as positron emission tomography (PET) imaging agents that localize to areas of hypoxia and help predict radiation response rates [11–13]. Therefore, redox active metal chelates may yet become the favored development candidates, a fact that is supported by the clinical success of arsenic trioxide (As2O3), a potent ROS generator [14, 15].

In this study, a copper chelate of the pyridine 2-carbaldehyde thiosemicarbazone NSC 689534 (NSC 689534/Cu2+) was evaluated relative to the unchelated form to gain further insight into the mechanism of action of this family of compounds. We found that the activity of NSC 689534 was influenced by the metal ion present; Fe2+/Fe3+inhibited while Cu2+enhanced antiproliferative activity. Microarray analysis of cells treated with NSC 689534/Cu2+ highlighted the importance of ER stress related pathways, autophagy and metal ion metabolism in activity. Results showed that inhibition of macroautophagy did not affect the activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ while conversely, inhibition of ER-stress prevented apoptosis, thus indicating that the ER stress response pathway plays an important role in activity. Lastly, in vivo studies showed that NSC 689534/Cu2+ was more efficacious than NSC 689534 in an HL60 xenograft model. Therefore, it may be worthwhile to investigate the utility of NSC 689534/Cu2+ as a treatment of malignancies with inherent defects in redox homeostasis or in combination with agents that impair the oxidative stress response.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and reagents

NSC 689534 was obtained from the Drug Synthesis and Chemistry Branch of the Developmental Therapeutics Program, National Cancer Institute (Rockville, MD). All cell lines were from the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis Tumor Repository (Frederick, MD). Materials were from the following: BCA Protein assay, Pierce (Rockford, IL); nitrocellulose membranes and polyacrylamide gels, Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); complete protease inhibitor tablets, Roche (Mannheim, Germany). All other chemicals were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified. Primary antibodies were from the following: PARP-1, Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA); GRP78, CHOP, HO-1, HSPA6, Abcam (Cambridge, MA); LC3, Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA) and β-Actin, Sigma (St. Louis,MO).

[14C]-leucine cell viability assays

Cells were plated into 96-well plates 24 h before treatment, and treated for 48 hours as indicated. To terminate the assay, serum-containing media was replaced with serum- and leucine-free RPMI 1640 containing 0.03 µCi of [14C]-leucine and the samples processed as described in Stockwin et al. [16]. Results are expressed as % [14C]-leucine incorporation into the control-treated cells. Experiments were performed at least twice with triplicate determinations for each point. The IC50 was defined as the concentration of drug required for inhibition of protein synthesis (cell viability) by 50% relative to control-treated cells.

Combination Studies

Dose response curves of NSC 689534/Cu2+ (0.01–10 µM) in combination with either buthionine sulphoximine (0.01–1 µM), arsenic trioxide (1–100 µM), cisplatin (0.03–3 µM), or bortezomib (0.003–0.3 µM) were assayed at multiple fixed ratios in the cell viability assays as described above. Combination indices (CI) were calculated using CalcuSyn software (Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) using pooled data from at least 2 experiments with triplicate determinations for each point.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Treated cells were harvested and fixed in 1 mL cold 70% ethanol, and stored at 4°C overnight. The cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 1 mL PBS containing 100 µg/ml propidium iodide (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR) and 200 µg/mL RNase A. Cells were incubated for 2 h at 37°C, and data aquired using the FL3-A channel of a Becton Dickenson FACScan flow cytometer controlled by Cellquest Pro software.

Apoptosis and Necrosis Determination

Apoptosis/necrosis was determined using the Vybrant Apoptosis Assay kit comprising an Annexin V–Alexa488 conjugate and propidium iodide as described by the manufacturer (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR). Acquisition and analysis of data was done using the FL1-H and FL3-H channels on a FACScan flow cytometer controlled by Cellquest Pro software.

Caspase 3/7 Activity Assay

Activity of Caspase 3/7 was determined using the CaspGlo fluorogenic assay according to manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Fluorescence intensity was determined using a Tecan Spectrofluorimeter (Research Triangle Park, NC).

Immunoblotting

Treated cells were harvested in RIPA-CHAPS buffer [50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mmol/L EDTA, 1% CHAPS, 1% deoxycholate, 1× complete protease inhibitor], and protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions. SDS-PAGE was done using 20 µg protein per well on a 4–12% Tris-glycine gel with subsequent transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane using the I-Blot transfer system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Following blocking in 5% milk/TBST for 2 hours, membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight, washed in TBST, and incubated with the peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (GE Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for 2 h. Bands were visualized using Visualizer Western Blotting Detection Kit (Millipore, Bedford, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Immunoblots were scanned using a Kodak Image Station 4000 Pro and captured using Kodak Molecular Imaging software.

Determination of dCTP Levels

CTP/dCTP was extracted from cells following the protocol described in Decosterd et al. [17]. After 1 day of treatment with 1µM NSC 689534 alone or in the presence of 2µM metals, HL60 cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS before the addition of equal volumes of ice cold H2O (1 × 106 cells/100 µL) and 6% TCA. The cell extracts were centrifuged at 4°C at top speed in a microfuge for 10 min before analysis on a Beckman 4.6 × 250mm Ultrasil AX 10µm column. The chromatography was performed in isocratic mode (0.3M KH2PO4, pH 3.0) at room temperature at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min as described by Arezzo [18]. A Waters 2487 dual absorbance wavelength detector was used to determine the integrated area for the peaks representing CTP and dCTP at 254 nm and 280 nm. CTP and dCTP were identified a) by comparing the retention times of standard CTP and dCTP with those peaks found in the lysate, b) by spiking in varying amounts of standard CTP and dCTP into the lysates and c) by comparing the spectral 254 nm: 280 nm ratios of the unknowns with the standard CTP and dCTP. The spectral ratios (254 nm:280 nm) for the treated samples were then represented as % control samples.

GSH/Protein Thiol Determination

Glutathione and total cellular protein sulfhydryl concentration was determined by the method of Shvedova et al. with minor modifications [19]. After treatment, cells were collected and counted. Equal numbers of cells from each treatment were seeded in triplicate into a black-walled, clear-bottomed 96-well plate. For determination of GSH levels, ThioGlo-1 (5 µM final concentration) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was added to each well and the relative fluorescence intensity measured using a Tecan Spectrofluorimeter controlled by Magellan software (Research Triangle Park, NC). For determination of relative levels of total protein sulfhydryl groups, SDS (4.0 mM final concentration) was added and the cells incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes prior to measuring fluorescence intensity.

ROS Generation

Cells were harvested and resuspended at approximately 1× 106/mL in serum-containing medium. CM-H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes, Eugene,OR) was added to media for 2h at a concentration of 10 µmol/L followed by 2 h of drug treatment. Alternatively, cells were treated overnight with drug, treated for 2 hours with DCFDA, and harvested. ROS generation was measured as the increase in green fluorescence and analyzed using the FL1 channel on a FACScan flow cytometer.

Acidic Vacuole Accumulation

Acidic vacuole (AVO) accumulation was assessed using the method of Malagoli et al [20]. Treated cells were stained with 5 µg/ml acridine orange for 5 minutes and harvested. Red fluorescence intensity (FL3-H) was measured using a FACScan flow cytometer. Alternatively, cells were grown on glass coverslips, treated as above, and AVO accumulation assessed using a Leica DM compound microscope (Rockville, MD).

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were grown until 60% confluent and treated as indicated for 48 hours. Coverslips were washed in PBS, and fixed using −20°C methanol. Cells were washed with permeabilization buffer (PBS, 4% BSA, 0.2% saponin) and then permeabilized for 1 hour. Coverslips were incubated with primary antibody in permeabilization buffer for 2 hours, washed, and then incubated with Alexa488-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Coverslips were mounted onto slides overnight using Slowfade mounting reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). All images were aquired using a Leica DM compound microscope (Rockville, MD).

Microarray Analysis

PC3 cells were cultured to 80% confluence in T75 flasks and treated with vehicle, 1µM NSC 689534 or 1µM NSC 689534/ 2µM Cu2+ for 24 hours. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of RNA was determined using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer, and the A260/A280 values were greater than 1.9. Microarray data were collected at the Laboratory of Molecular Technologies (SAIC-Frederick, Frederick, MD) using the GeneChip® Human U133 plus 2.0 Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara CA), according to standardized operating procedures. Duplicate arrays were hybridized for each of the three experimental variables (vehicle, NSC 689534, NSC 68953/Cu2+). The Genesifter suite (VizX labs, Seattle, WA) was then used for analysis of microarray data. In brief, raw data files (.CEL) containing array data were loaded into the Genesifter web portal http://www.genesifter.net website. Using the advanced upload function, probe-level data was then compiled, normalized and transformed using GC-RMA. Pairwise analysis was then performed comparing control with drug treated arrays. The following criteria were applied to filter the differentially expressed transcript list, a fold change of >3 and a Wilcoxon rank sum test where p < 0.05 with Benjamini-Hochberg estimation of false discovery rate (FDR). The list of differentially regulated transcripts was then exported into excel for gene ontogeny analysis. Affymetrix array data files (.CEL) have been deposited with the Gene Expression omnibus and are also available on request.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400 spectrometer. All spectra were recorded in HPLC grade CH3CN and 99.9 % DMSO-d6 (NMR buffer). To obtain the internal standard NMR peak, the NMR buffer containing 0.03% TMS was scanned. For the first run, NSC 689534 alone at 1mg/mL (2.8 mM) in NMR buffer was scanned at room temperature to obtain the neat NMR spectrum (Drug only). Next 0.056 mM (0.02 equivalents) (20µL of 2.8 mM copper chloride) was added to the drug only solution and the mixture scanned. This was repeated until a total of 0.4 equivalents of copper had been added to the drug only solution.

HL60 Xenograft Model

Human tumor xenografts were generated in 4–6 week old female athymic nude mice (nu/nu NCr) by serial passage of tumor fragments from donor mice as described previously [21]. The donor tumors were produced by subcutaneous injection of 1 × 107 HL-60 tumor cells grown in vitro using RPMI 1640 with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine. The mice were housed in an AAALACi-accredited facility with food and water provided ad libitum. When tumors reached the predetermined starting weight (staging weight), the animals were randomized into experimental groups and treatment was initiated. Groups included a vehicle control group (10% DMSO in 0.9% saline) (n = 14) and 4 drug treated groups (n = 7). Drug doses were selected based upon single mouse toxicity studies as described elsewhere [21]. Tumors were monitored by bidirectional caliper measurements and the tumor weights were calculated as tumor weight (mg) = (tumor length in mm × tumor width in mm2)/2. Antitumor effects were assessed as described previously [21] using optimal %T/C and by statistical analysis using Student’s t-test.

Results

Cytotoxicity of the thiosemicarbazone, NSC 689534, is differentially modulated by copper and iron

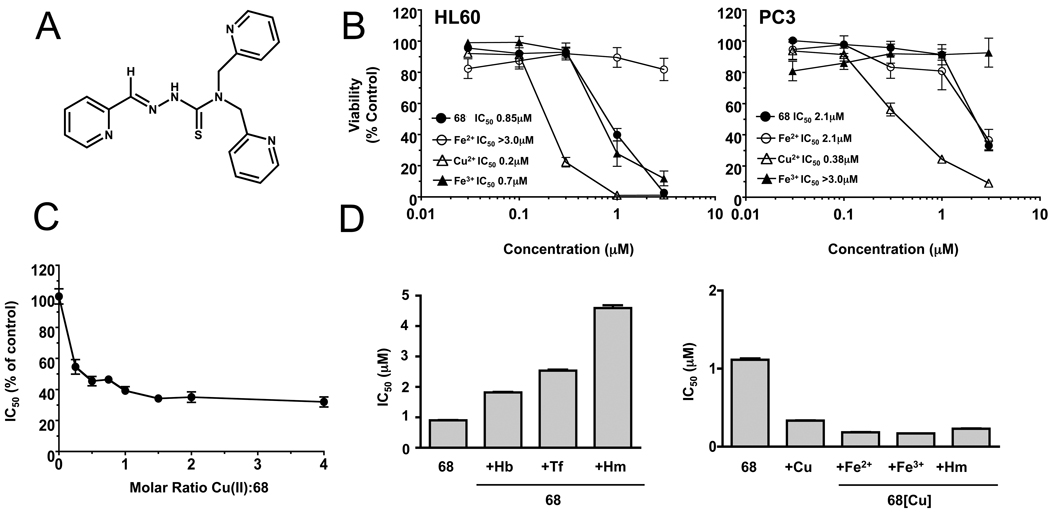

NSC 689534 (2-pyridinecarbaldehyde N,N-bis(2-pyridinylmethyl)thiosemicarbazone) is a member of the heterocyclic thiosemicarbazone family of compounds (for structure see Fig. 1A). This agent was first evaluated for cytotoxicity against HL60 (monocytic leukemia) and PC3 (prostate carcinoma) cell lines over the course of 3 days, using the 14C-leucine viability assay (Supplementary Fig. 1). Results showed that HL60 cells were more sensitive to NSC 689534 than PC3 cells following the first 2 days of exposure but by day 3 both cell lines were inhibited similarly (day 3 IC50, 50 and 120 nM, PC3 and HL60 cells, respectively) (see Supplementary Fig. 1). It has been shown that the chelation of transition state metals markedly alters the biological activity of thiosemicarbazones [22]. As shown in Fig. 1B, iron inhibits the antiproliferative activity of NSC 689534. Interestingly, inhibition varied with the redox state of iron; NSC 689534/Fe2+ inhibited proliferation of HL60 cells while the Fe3+ chelate was the inhibitory form for PC3 cells. Conversely, copper enhanced the activity of NSC 689534 by approximately 4–5 fold toward both cell lines (IC50 0.85 vs 0.2 and 2.1 vs 0.4 µM in the absence and presence of Cu2+ for HL60 and PC3 cells, respectively). Interestingly, measurements of intracellular copper showed that in contrast to treatment with copper alone, NSC 689534/Cu2+ effectively elevated Cu2+ levels in the cytosol (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Copper chelation enhances the anti-proliferative activity of NSC 689534. A) Structure of NSC 689534. B) HL60 and PC3 cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of NSC 689534 (68) or NSC 689534 pre-incubated with 2 molar equivalents of Fe(II), Fe(III), or Cu(II) for 48 hours before viability was determined. C) Plot of the IC50 values as % of control obtained for dose response curves. IC50s were determined for NSC 689534 containing 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 and 4.0 mols of copper per mol thiosemicarbazone. The IC50s are plotted as a % of no copper (control) versus molar ratio of Cu2+ to NCS 689534. D) HL60 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of NSC 689534 alone or in combination with 2.5µM hemoglobin (Hb), 100 µg/ml transferrin (Tf), or 10 µM hemin (Hm) (left panel) or with increasing concentrations of NSC 689534/Cu2+ alone or in combination with 20 µM Fe (II), 20 µM Fe (III), or 10 µM Hemin (Hm) (right panel) for 48 hours and viability determined. IC50 values obtained are plotted versus each treatment condition. 68[Cu] refers to NSC 689534 in the presence of a 2 fold molar ratio of Cu2+. Assays were performed at least twice with triplicate determinations for each point and the data pooled. The SEM of six determinations is shown when they are greater than the symbol or bar

To determine the optimal ratio of Cu2+ to thiosemicarbazone required for maximal activity, dose response curves were generated varying the ratio of Cu2+ to NSC 689534. Fig. 1C shows a plot of the IC50 values obtained for each dose response curve plotted as a % of control (no Cu2+) versus the molar ratio of Cu2+:NSC 689534. Maximal activity occurred at a 1:1 molar ratio of Cu2+:NSC 689534. A further increase in ratio to 4:1 did not result in any further significant increase in activity. Results from NMR analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 2) confirmed that NSC 689534 chelated Cu2+ and further demonstrated that the increase in activity was due to NSC 689534/Cu2+ chelate and not to the formation of a new structural entity such as would occur following desulfurization or the formation of a bidentate ligand [23]. Additionally, Cu2+ alone up to 40µM had no effect on viability (data not shown), indicating that copper toxicity was not responsible for the increase in antiproliferative activity. To ensure maximal activity, the remaining in vitro assays utilized 2 mols Cu2+ per mol NSC 689534 unless stated otherwise.

Next, activity of NSC 689534 was examined in the presence of iron-containing biomolecules. As shown in Fig. 1D (left panel), the activity of NSC 689534 was inhibited 2–5 fold in the presence of hemoglobin, transferrin and hemin (IC50s; 0.9 µM, 1.8 µM, 2.5 µM and 4.5 µM, for NSC 689534 alone or in the presence of 2.5 µM hemoglobin, 100 µg/mL transferrin or 10µM Hemin, respectively), supporting previous studies showing that thiosemicarbazones can chelate iron from biological molecules [22]. For the copper chelate to be therapeutically relevant, NSC 689534/Cu2+ needs to retain activity in the presence of iron-containing biomolecules. As shown in Fig. 1D (right panel), cytotoxic activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ was not affected by the presence of excess Fe2+, Fe3+ or the biologically bound iron in hemin, indicating that the NSC 689534/Cu2+ complex is stable. Further support for preferential copper binding in the presence of iron is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, where exposure of NSC 689534 to Cu2+/Fe3+ mixtures generated chelates that retained the IC50 of NSC 689534/Cu2+.

Thiosemicarbazones are potent inhibitors of ribonucleotide reductase (RR) [24, 25]. To evaluate whether or not NSC 689534 alone or as an Fe2+ or Cu2+ chelate affected RR activity, we followed the conversion of the ribonucleotide, CTP, to the deoxyribonucleotide, dCTP. Lysates were prepared from HL60 cells treated with 1µM thiosemicarbazone either alone or in the presence of metals and an HPLC-based assay was used to measure RR activity. Results demonstrated that only the copper chelate was effective in inhibiting the conversion of CTP to dCTP (% control: 107.4 ± 7.9%, 106.9 ± 5.7%, and 71.9 ± 3.3% for 1µM NSC 689534 alone, +Fe2+, and +Cu2+) (Data not shown). Additionally, NSC 689534/Cu2+ was more potent than hydroxyurea, a known inhibitor of RR (% control, 69.5 ± 1.9% for 50 µM hydroxyurea) (Data not shown) [26].

NSC 689534 and NSC 689534/Cu2+ are mechanistically distinct and have cell-type specific effects

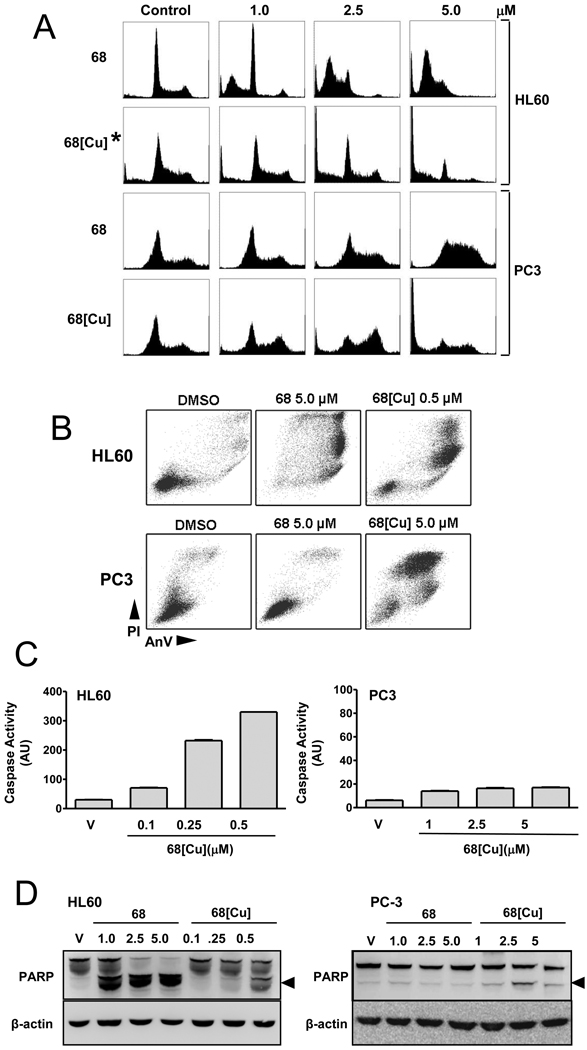

Cell lines were then treated with NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ at a range of concentrations and analyzed for cell cycle perturbations (Fig. 2A). Results demonstrated that HL60 cells treated with NSC 689534 arrested in G1 with a substantial increase in the sub-Go population of cells indicative of apoptosis. Treatment with 10 fold lower concentrations of the Cu2+ chelate caused a dose-dependent increase in the sub Go population of cells but with no G1 arrest. For PC3 cells, treatment with the non-chelated thiosemicarbazone resulted in a dose-dependent arrest in S-phase without a sub-Go population whereas NSC 689534/Cu2+ caused the cells to arrest in G2M with a dose-dependent increase in Go that was especially evident at 5µM. These cell cycle perturbations prompted us to question whether NSC 689534/Cu2+ mediates effects through direct DNA damage. However, in the context of comet assays, NSC 689534/Cu2+ only appeared able to induce damage in HL60 cells and not PC3 cells, and moreover these effects were only visible after 24 hours (Supplementary Fig. 4). These data suggest that NSC 689534/Cu2+ is not immediately genotoxic.

Fig. 2.

NSC 689534/Cu2+ induces apoptosis in HL60 and mainly necrosis in PC3 cells. (A) HL60 and PC3 cells were treated for 48 h with either NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ at the indicated concentrations. This was followed by fixation in 70% ethanol, labeling with propidium iodide (PI) and analysis by flow cytometry for cell cycle perturbations. *HL60 cells shown were treated with a 10 fold lower dose than indicated on axis (0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 µM). B) Analysis of apoptosis induction for HL60 and PC3 cells treated with NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ by flow cytometry using Annexin V/PI staining. (C) HL60 or PC3 cells were treated with either DMSO (vehicle) or the indicated concentration of NSC 689534/Cu2+, and caspase cleavage assessed after 24 or 48 hours, respectively. The SEM is shown when greater than the bar. (D) HL60 and PC3 cells were treated with either vehicle or the indicated concentration of NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ for 24 or 48 hrs, respectively and cleavage of PARP-1 assessed using immunoblotting as described in Materials and Methods. The arrow denotes the predominant 89 kDa PARP cleavage product. Results are representative of three separate experiments.

Next, levels of apoptosis were determined using Annexin V/PI staining. Results in Fig. 2B illustrate that in HL60 cells both the thiosemicarbazone alone and the copper chelate induce apoptosis, with the chelated form being more active. With PC3 cells, 5µM NSC 689534 had little effect on levels of apoptosis or necrosis, whereas 5µM NSC 689534/Cu2+ markedly increased levels of necrosis with some evidence for apoptosis induction. To address the low level of apoptotic death in PC3 cells, we determined whether treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ resulted in activation of the effector caspases 3 and 7 (Fig. 2C). Whereas caspase activation was markedly induced at 24 hrs in HL60 cells in a dose dependent manner, only a low level of activation occurred in PC3 cells even after 48 hrs of treatment. Additionally, cleavage of PARP-1, an early event in apoptosis catalyzed by caspase 3, occurred in HL60 cells 24 hrs following treatment with both NSC 689534 and NSC 689534/Cu2+ while very low levels of PARP-1 cleavage were noted for PC3 cells at 48 hrs (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, pre-treatment with the caspase-inhibitor z-VAD-FMK had no effect on overall levels of cell death for either cell line following treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+, suggesting that several death pathways are concurrently active [data not shown].

Microarray analysis of NSC 689534/Cu2+ treated cells

To provide an objective assessment of transcripts and pathways altered by NSC 689534/Cu2+, treated cells were then subjected to microarray analysis. Control PC3 cells or those treated for 24 hr with 1µM NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ were harvested, RNA isolated, cDNA synthesized and hybridized to duplicate Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 cDNA arrays. Pairwise analysis was then performed using control vs. treated arrays using a fold change cut-off of >3 and a t-test (p < 0.05) with a Benjamini-Hochberg estimation of false discovery rate (FDR). Treatment with NSC 689534 resulted in differential expression of 296 transcripts (22 downregulated, 274 upregulated) whereas for NSC 689534/Cu2+ 2156 transcripts were modulated (1046 downregulated, 1110 upregulated). These results are shown in Supplementary Table 1. This almost 10-fold difference in altered transcripts between non-chelated and Cu2+-chelated forms suggests a more profound response to NSC 689534/Cu2+.

The transcript list from NSC 689534/Cu2+ was then subjected to gene ontology analysis and subdivided according to biological pathway (Table 1). From this analysis, it was evident that the transcriptome was enriched in genes implicated in the response to oxidative stress. Increased expression was observed for sensors and mediators of the response to stress; ATF3 (up 104 fold) and several growth arrest and DNA-damage inducible transcripts e.g. GADD34 (up 27.9 fold). Significant numbers of oxidative stress response effectors also showed elevated expression e.g. metallothioneins, e.g. MT1M (up 2094.9 fold) and MT1F (up 231.5 fold). Similarly, mRNA coding for the anti-oxidant HMOX1 increased 229.2 fold, as did several genes involved in glutathione synthesis, including GCLC (up 5.6 fold), GCLM (up 5.8 fold) and SLC7A11 (up 33.8 fold). Upregulation of transcripts such as GRP78 (up 4.9 fold), HSPA6 (up 233 fold), XBP1 (up 3.4 fold), and CHOP (up 17.8 fold), suggested that a more specialized response pathway, the unfolded protein response (UPR), was active. In addition, we detected upregulation of transcripts involved in macroautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) including; LC3 (up 8.9 fold), LAMP2 (up 3.5 fold) and LAMP3 (up 146 fold), where both autophagic responses can be induced by prolonged oxidative and ER stress. Finally, expression of metal ion binding/transporter transcripts such as the zinc transporter ZNT1 (up 55.1 fold), the calcium binding protein S100P (up 77.2 fold) and the previously mentioned metallothioneins, suggests that the cell is also attempting to counter excess Cu2+. Taken together, these data indicate that treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ results in the induction of diverse pathways involved in countering both oxidative stress and Cu2+ overload.

Table 1.

Microarray analysis of PC3 cells treated with NSC 689534/Cu2+

| Symbol | Gene Name | Fold Change | Affymetrix ID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Stress Response | ATF3 | Activating transcription factor 3 | 104.0 | 202672_s_at |

| FYN | protein-tyrosine kinase fyn | 6.7 | 216033_s_at | |

| GADD34 | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 34 | 27.9 | 202014_at | |

| GADD45A | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, alpha | 3.3 | 203725_at | |

| GADD45B | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, beta | 14.57 | 209305_s_at | |

| GADD45G | growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible, gamma | 19.9 | 204121_at | |

| General Oxidative Stress | AKR1C1 | aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C1 | 44.7 | 204151_x_at |

| MT1E | Metallothionein 1E | 13.5 | 212859_x_at | |

| MT1F | Metallothionein 1F | 231.5 | 217165_x_at | |

| MT1G | Metallothionein 1G | 22.7 | 204745_x_at | |

| MT1H | Metallothionein 1H | 13.9 | 206461_x_at | |

| MT1L | Metallothionein 1L | 23.5 | 204326_x_at | |

| MT1M | Metallothionein 1M | 2094.86 | 217546_at | |

| MT1X | Metallothionein 1X | 15.3 | 208581_x_at | |

| MT2A | Metallothionein 2A | 8.1 | 212185_x_at | |

| Nrf2-Mediated Oxidative Stress | AOX1 | aldehyde oxidase 1 | 10.3 | 205083_at |

| BACH1 | BTB and CNC homology 1, transcription factor 1 | 4.3 | 204194_at | |

| CTH | cystathionase | 10.0 | 206085_s_at | |

| DNAJA4 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 4 | 12.3 | 1554333_at | |

| FOS | v-fos FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog | 34.7 | 209189_at | |

| FTH1 | ferritin, heavy polypeptide 1 | 3.6 | 214211_at | |

| FTL | ferritin, light polypeptide | 5.2 | 213187_x_at | |

| GCLC | glutamate-cysteine ligase, catalytic subunit | 5.6 | 1555330_at | |

| GCLM | glutamate-cysteine ligase, modifier subunit | 5.8 | 236140_at | |

| GSK3B | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | 3.1 | 209945_s_at | |

| HMOX1 | heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 | 229.2 | 203665_at | |

| MAFF | v-maf oncogene homolog F (avian) | 7.3 | 36711_at | |

| MAFG | v-maf oncogene homolog G (avian) | 5.3 | 204970_s_at | |

| SLC7A11 | cystine/glutamate transporter | 33.8 | 207528_s_at | |

| SQSTM1 | sequestosome 1 | 23.4 | 213112_s_at | |

| ER-Stress/UPR | CASP4 | caspase 4, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | 7.2 | 209310_s_at |

| CBLB | SH3-binding protein CBL-B | 5.0 | 209682_at | |

| DDIT3 (CHOP) | DNA-damage-inducible transcript 3 | 17.8 | 209383_at | |

| DNAJB4 | Heat shock protein 40 homolog | 8.1 | 203810_at | |

| DNAJB9 | Endoplasmic reticulum DnaJ homolog 4 | 27.3 | 202842_s_at | |

| DNAJC3 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily C, member 3 | 3.96 | 1558080_s_at | |

| HERPUD1 | homocysteine-inducible, endoplasmic reticulum protein | 8.4 | 217168_s_at | |

| HSPA13 (STCH) | heat shock protein 70kDa family member 13 | 10.6 | 202558_s_at | |

| HSPA1A | heat shock 70kD protein 1A | 4.8 | 200800_s_at | |

| HSPA5 (GRP78) | heat shock 70kDa protein 5 (glucose-regulated protein, 78kDa) | 4.92 | 230031_at | |

| HSPA6 (HSP70B) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein B' | 233.0 | 213418_at | |

| SERPINH1 | Serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade H | 5.0 | 207714_s_at | |

| TRIB3 (SKIP3) | Tribbles homolog 3 | 28.3 | 1555788_a_at | |

| XBP1 | X-box binding protein 1 | 3.44 | 200670_at | |

| p53 Signalling | CDKN1A | cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (p21, Cip1) | 19.58 | 202284_s_at |

| JMY | junction mediating and regulatory protein, p53 cofactor | 4.47 | 241985_at | |

| JUN | jun oncogene | 3.31 | 201465_s_at | |

| MDM4 | Mdm4 p53 binding protein homolog (mouse) | 3.98 | 225742_at | |

| PRG1 | proteoglycan 1, secretory granule | 195.12 | 201859_at | |

| THBS1 | thrombospondin 1 | 10.39 | 201108_s_at | |

| TNFRSF10B | tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10b | 3.06 | 209295_at | |

| Autophagy | ATG18 (WIPI1) | WD repeat domain, phosphoinositide interacting 1 | 6.1 | 203827_at |

| CTSD | Cathepsin D | 8.9 | 200766_at | |

| DNAJB1 (HSPF1) | Heat shock 40 kDa protein 1 | 5.2 | 200666_s_at | |

| HSPB8 (HSP22) | heat shock 27kDa protein 8 | 4.8 | 221667_s_at | |

| LAMP2 | Lysosomal Membrane Protein 2 | 3.5 | 203041_s_at | |

| LAMP3 (TSC403) | DC-lysosome-associated membrane glycoprotein | 146.0 | 205569_at | |

| MAP1LC3B (LC3) | Autophagy-related protein LC3 B | 8.9 | 208786_s_at | |

| Metal Ion Binding/Transport | S100P | S100 calcium binding protein P | 77.2 | 204351_at |

| ZNT1 | solute carrier family 30 (zinc transporter), member 1 | 55.1 | 228181_at |

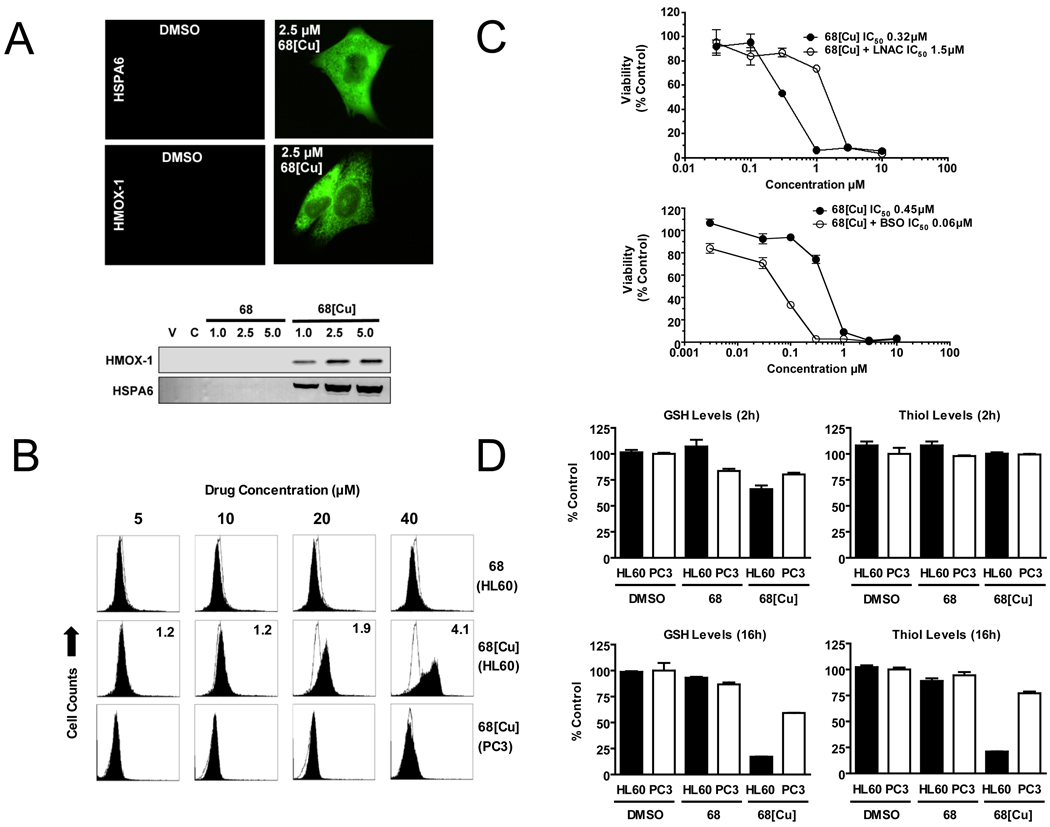

NSC 689534/Cu2+ induces oxidative stress and depletes GSH

Heme oxygenase (HMOX1) and heat shock 70kDa protein B (HSPA6) are both oxidative stress-response proteins whose transcript expression was elevated by NSC 689534/Cu2+ treatment. Using immunoblotting and immunocytochemistry, levels of both HMOX1 and HSPA6 polypeptide were markedly elevated following treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ (Fig. 3A). This result provided overall validation of microarray data and reaffirms the importance of oxidative stress in drug activity. We next investigated the redox effects of NSC 689534/Cu2+ using several cell-based assays. Cells were treated for 2 hr with varying concentrations of NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ followed by the addition of the fluorescent ROS sensor, CM-H2-DCFDA. Oxidation of CM-H2-DCFDA by ROS generates the green fluorescent molecule, DCF, which can then be quantified by flow cytometry. For HL60 cells, there was no change in fluorescence following treatment with NSC 689534 alone whereas treatment with the copper chelate caused a dose dependent increase in ROS production (Fig. 3B). At 40µM NSC 689534/Cu2+, fluorescence increased 4 fold over control treated cells. In contrast, no ROS generation was detected in PC3 cells treated with NSC 689534/Cu2+ for 2 h. Increasing the time of incubation with the copper chelate to overnight resulted in a 2.2 fold increase in ROS production at 5µM NSC 689534/Cu2+ compared to no change in fluorescence with NSC 689534 alone under the same conditions (data not shown). Next, the cytotoxic activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ was determined in the presence of the antioxidant, L-NAC. As shown in Fig. 3C (upper panel), the addition of L-NAC resulted in a 4.7-fold attenuation of NSC 689534/Cu2+ activity (IC50 0.32 µM and 1.5 µM in the absence or presence of 12 mM L-NAC, respectively). Inclusion of the antioxidant, ascorbate, or the antioxidant enzyme, catalase, or diethyldithiocarbamate, an inhibitor of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase attenuated the activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ by 2, 4.4 and 2 fold respectively (data not shown). Furthermore, the combination of NSC 689534/Cu2+ with an inhibitor of glutathione synthesis, butathione sulfoximine (BSO), was highly synergistic, producing a combination index (CI) of 0.16 where CI’s <0.8 indicate synergy and 0.8–1.2 indicate additivity. As shown in Fig 3C (lower panel), BSO enhanced the activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ 8-fold. To explore the role of glutathione in more depth, ThioGlo-1, a reagent that produces a highly fluorescent product upon reaction with thiol (SH) groups, was then used to determine whether NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ depleted cellular GSH. Total protein thiol groups were determined by adding SDS to the same cell lysate to unfold proteins. Following 2 hrs of treatment, NSC 689534 caused little or no effect on either GSH or total protein thiol levels in HL60 or PC3 cells (Fig. 3D, top panels). NSC 689534/Cu2+ reduced GSH levels to 66% of control in HL60 cells and showed no change in PC3 cells. There was no significant change in protein thiol levels for either cell line. Following 16 h of treatment, NSC 689534 treatment still caused no change in GSH or thiol levels whereas treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ reduced GSH levels to 18% and 60% of control for HL60 and PC3 cells, respectively (Fig. 3D, left bottom panels). At this time point, total protein thiol levels decreased to 21% and 77% of control, HL60 and PC3 cells, respectively (Fig 3D, bottom right panel). Overall, these results show that oxidative stress is at least partially responsible for NSC 689534/Cu2+ cytotoxicity.

Fig. 3.

NSC 689534/Cu2+ anti-cancer activity is ROS-mediated. A) PC3 cells were treated with 2.5 µM NSC 689534 or 2.5 µM NSC 689534/Cu2+ for 24 hours and then analyzed for expression of HSPA6 and HMOX1 by immunocytochemistry and immunoblotting. B) Cell lines were labeled for 2h with the fluorescent ROS sensor DCFDA and then treated for 2h with the indicated concentration of NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ followed by analysis by flow cytometry (FL1 channel). DCF fluorescence of the indicated treatment (solid profile) is shown compared to vehicle control (open profile). Inset values indicate fold increase in DCFDA fluorescence versus control. C) HL60 cells were treated with the indicated concentration of NSC 689534/Cu2+ alone or in the presence of 12 mM L-NAC (top panel) or 1µM BSO (bottom panel) for 24 h, followed by viability determination. Results are representative of three separate experiments. D) HL60 (black bar) or PC3 cells (open bar) were incubated for 2 or 16 hrs with vehicle, NSC 689534, or NSC 689534/Cu2+. Following this, GSH and total cellular thiol levels were determined as described in Materials and Methods and results plotted as % control.

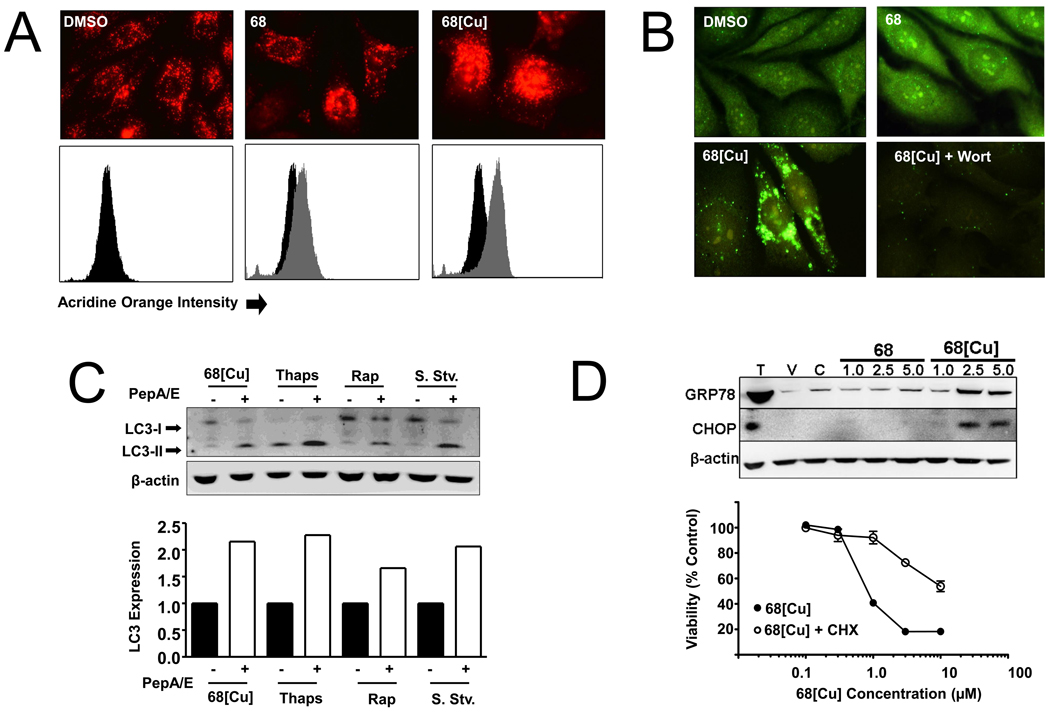

NSC 689534/Cu2+ induces both macroautophagy and an ER-stress response

Having observed upregulation of several transcripts involved in macroautophagy, we next determined whether this process was playing a role in the cytotoxic effects of NSC 689534/Cu2+. To this end, we first used an acridine orange cell-staining assay to detect changes in cellular acidic compartments indicative of induction of autophagy [27]. Acridine orange is a lysosomotrophic compound that freely diffuses across cell membranes when uncharged and accumulates in acidic vesicular organelles (AVO) upon protonation producing a bright red fluorescence. Cells treated with NSC 689534/Cu2+ showed intense red fluorescence compared to control cells or cells treated with NSC 689534 (Fig. 4A, upper panel). This result was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4A, lower panel). These data are consistent with the induction of autophagy wherein cytoplasm and organelles are sequestered in autophagic vesicles with subsequent delivery to the cell’s lysosomal compartment for degradation.

Fig. 4.

NSC 689534/Cu2+ treatment is associated with macroautophagy and ER-stress induction. A) (Upper panel) PC3 cells were plated onto coverslips and treated with DMSO, 2.5 µM NSC 689534 or 2.5 µM NSC 689534/Cu2+ for 24 hours followed by labeling with acridine orange for 2 hours and visualization by microscopy. (Lower panel) A second set of samples were also prepared and analyzed by flow cytometry (treated samples in gray, control samples in black). B) PC3 cells on glass coverslips were treated with either vehicle (DMSO), 2.5 µM of NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+, or a combination of NSC 689534/Cu2+ and 200 µM wortmannin for 48 hours, fixed and stained with an anti-LC3 antibody and visualized by microscopy at 60× magnification. C) Cells were treated with either 2.5 µM NSC 689534/Cu2+, 25 nM of thapsigargin, 50 µM of rapamycin, or serum starved either alone or in combination with 10 µM of Pepstatin A and E64d for 48 hours, then harvested and immunoblotted for conversion of LC3-I (upper band) to LC3-II (lower band). Densitometry (lower panel) was included to assess fold expression of LC3-II in the Pepstatin A/E64d treated versus drug alone. D) (upper panel) PC3 cells were treated with 1, 2 or 5 µM NSC 689534 or NSC 689534/Cu2+ for 24 hours, harvested and immunoblotted for expression of the ER-stress markers GRP78 and CHOP. Lysate from thapsigargin (T) treated PC3 cells was included as a positive control. V refers to vehicle treated cells (DMSO) and C indicates treatment with 100µM Cu2+. (lower panel) PC3 cells were treated with the indicated concentration of NSC 689534/Cu2+ alone or in combination with 1 µg/ml cycloheximide for 48 h. Cell viability was determined using crystal violet staining as described in Materials and Methods. Each value represents the mean +/− SEM of three independent measurements. The experiment was performed twice.

LC3 is widely used to detect autophagy [28]. The cleavage of LC3 generates a cytosolic form, LC3-I, and a membrane bound form, LC3-II (LC3-phosphatidylethanolamine conjugate). LC3-II colocalizes to autophagosomes and autolysosomes where degradation takes place by lysosomal hydrolases. Thus one indicator of macroautophagy induction is the relocalization of the LC3 protein from a diffuse cytosolic distribution to more punctuate staining with the formation of autophagosomes [29]. Treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ resulted in LC3 accumulation into large autophagosomes; this accumulation was inhibited by wortmannin, an inhibitor of the initial stages of autophagy (Fig. 4B). These data confirm that treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ induces macroautophagy in PC3 cells. Additionally, failure of autophagosomes to fuse with lysosomes leads to their accumulation in cells and can result in cell death [30]. The lysosomal protease inhibitors Pepstatin A and E64d can be used to assess LC3 turnover rate, an indicator of whether autophagy is proceeding to completion [31]. In order to assess LC3 turnover rate, we treated cells with NSC 689534/Cu2+ or the autophagy-inducing compounds rapamycin and thapsigargin alone or in combination with Pepstatin A/E64d. Treatment with each in combination with Pepstatin A/E64d resulted in accumulation of LC3-II to levels approximately 1.5–2.5 fold higher than drug alone (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that cell death is not due to inhibition of autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Macroautophagy has been implicated both as a cytoprotective mechanism as well as a process that, when induced under prolonged periods of stress, can result in the induction of apoptosis. In order to determine the role of macroautophagy during NSC 689534/Cu2+-induced stress, we pretreated cells with either wortmannin or 3-MA, both inhibitors of autophagy, and then treated with NSC 689534/Cu2+. Inhibition of macroautophagy by either wortmannin or 3-MA had no affect on the antiproliferative activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ (data not shown). Together, these results indicate that although macroautophagy is being induced, it cannot sufficiently protect cells from NSC 689534/Cu2+-associated stress, nor is it necessary for the induction of cell death.

Given the observed upregulation of transcripts coding for the ER stress proteins GRP78 and CHOP, two key mediators of the ER stress response (Table 1), we next sought to determine whether ER stress played a role in the mechanism of NSC 689534/Cu2+. We verified upregulation of both GRP78 and CHOP at the protein level after treatment with NSC 689534/Cu2+ but not with NSC 689534 alone (Fig. 4D, upper panel). We next determined whether ER stress was involved in the cytotoxicity of NSC 689534/Cu2+. Cells were treated either with NSC 689534/Cu2+, the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, or both. Cycloheximide antagonizes ER stress agents, and inhibits ER stress-induced cell death by reducing the protein burden on the ER [32]. Co-treatment with cycloheximide significantly inhibited the anti-proliferative effects of NSC 689534/Cu2+, increasing the IC50 of NSC 689534/Cu2+ from 0.8 µM to greater than 10 µM (Fig. 4D. lower panel). This data indicates that NSC 689534/Cu2+ induces ER-stress and that this pathway plays an important role in cell death.

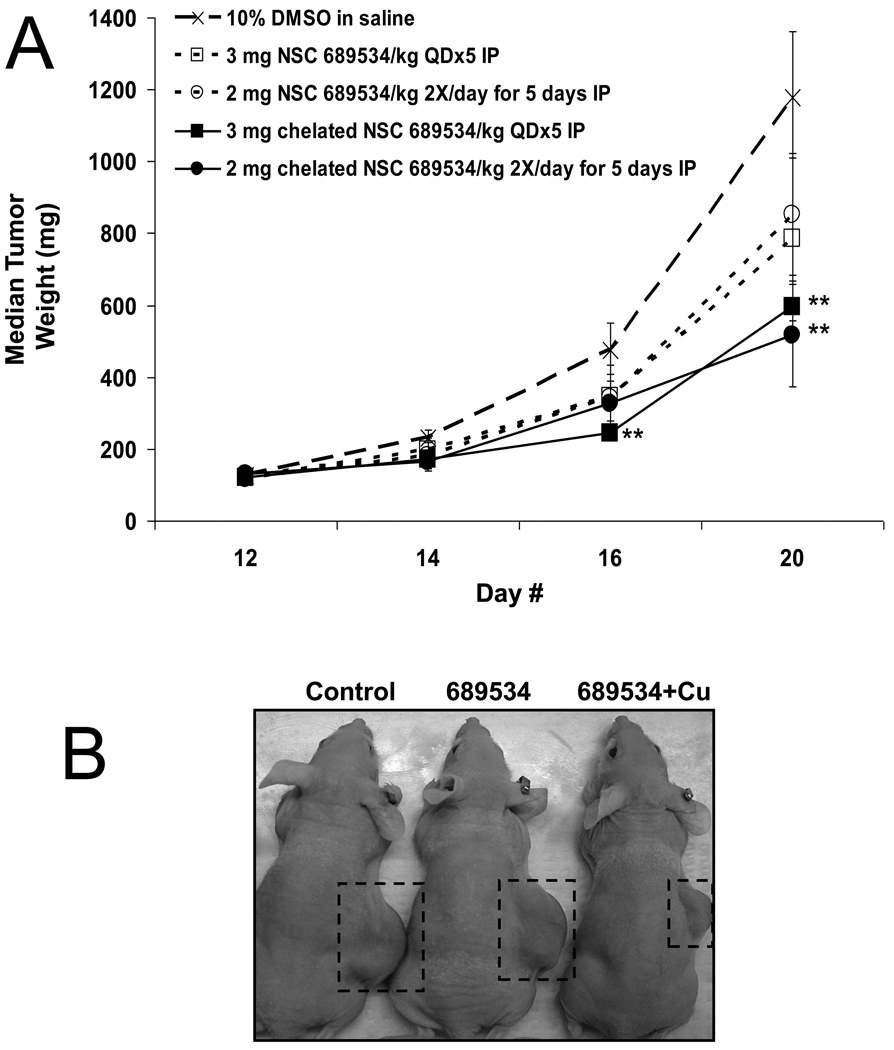

The copper chelate of NSC 689534 is active in vivo

NSC 689534 solubilized in 100% DMSO and administered as a single bolus intravenous (iv) injection (1 uL/gm body weight) at 100 mg/kg was tolerated without weight loss. When suspended in 0.9% saline containing 0.05% Tween 80, mice tolerated a single ip bolus dose of 200mg/kg without weight loss. In contrast, when NSC 689534 was chelated with copper prior to administration the maximum tolerated dose was reduced to 15 mg/kg given iv or 10 mg/kg given ip. Repeat dosing with the chelated compound was possible at 15 mg/kg iv for 5 days or 3 mg/kg ip for 5 days. Efficacy of the NSC 689534 and the chelated NSC 689534 was assessed against HL-60 human tumor xenografts. As shown in Fig. 5A, the mice receiving NSC 689534 chelated with copper whether given 5 daily ip bolus doses or twice daily dosing for 5 days had statistically significant reductions (p <0.05) in tumor size at days 20 or 16 and 20, respectively. In contrast, while there was evidence of tumor growth suppression in mice receiving NSC 689534 alone it did not achieve statistical significance (p < 0.05) on either dosing schedule. The chelated NSC 689534 treatments produced optimal % T/C values of 42% and 34% for the single and twice daily doses, respectively. The optimal %T/Cs for NSC 689534 given once (3 mg/kg/dose) or twice (2 mg/kg/dose) daily were both 54%. While the mice treated with chelated NSC 689534 did have statistically significant reductions in tumor weights compared to controls, there was not a statistically significant difference between the NSC 689534 and the chelated NSC 689534 treated groups. As to toxicity, no animals were lost to toxicity and the weight loss in all groups was less than 20% of their starting body weights. For comparison, the greatest weight loss (19%) occurred in mice receiving only CuCL2 at 1.12 mg/kg/dose daily for 5 days (no antitumor activity noted). The group receiving 2 mg/kg of the chelated NSC 689534 twice daily had 16% body weight loss while all other groups lost 1.8 – 5.8% over the course of the study. While none of the treatments produced tumor free animals, it is worth noting the chelation of copper to the NSC 689534 molecule did enhance in vivo activity in the HL-60 human tumor xenograft model (see Fig. 5B for a comparison of tumor sizes at termination of the experiment).

Fig. 5.

NSC 689534/Cu2+ has in vivo activity in an HL60 xenograft model. (A) Graph of effects of once or twice daily doses of 689534 or 689534[Cu] on growth rates in an HL60 xenograft. ** represents statistically significant differences from control at p < 0.05. B) Photograph of representative animals at termination of the experiment.

Discussion

Thiosemicarbazones, such as NSC 689534, are high-affinity metal-ion chelators where biological activity is markedly different between unconjugated and metal-bound forms [33–35]. In this study, we provide evidence that a copper-chelate of NSC 689534 has properties worthy of further pre-clinical evaluation. Although NSC 689534 binds iron and copper, only the Cu2+ chelate has activity in the nanomolar range. Furthermore, once copper is chelated, exogenous free iron, transferrin, heme or hemoglobin have a negligible impact on activity, a fact that is important for in vivo evaluation. As regards the mechanism of action, NSC 689534/Cu2+ induced apoptosis with no cell cycle arrest in HL60 cells, and caused a G2M block followed by mainly necrosis in PC3 cells. Non-apoptotic cell death (paraptosis) has also been shown for another Cu2+ complex agent, the thioxotriazole copper II complex A0, wherein treatment was associated with ER stress/UPR [36]. These effects were determined to be a direct consequence of increases in ROS with one consequence being reduced levels of glutathione and total protein thiols. The involvement of ROS in activity was further illustrated by experiments showing that the anti-oxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine protected cells from NSC 689534/Cu2+ whereas buthionine sulfoximine, a GSH biosynthesis inhibitor, was shown to synergize with NSC 689534/Cu2+. These results mirror those obtained in a study with the copper thiosemicarbazone, 2-formylpyridine (2-FP)/Cu2+, which also showed generation of ROS, depletion of GSH and oxidation of protein thiols [9].

Microarray analysis supported and extended these findings by showing activation of pathways involved in oxidative and ER-stress/UPR responses, autophagy and metal ion clearance. Prolonged oxidative damage to proteins results in ER stress and the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is an attempt by the cell to relieve ER stress by reducing overall translation and increasing the folding capacity of the ER [37, 38]. Although the UPR is a prosurvival response, it can also lead to apoptosis under conditions of chronic ER stress [39]. GRP78 is a member of the HSP family of proteins that facilitates transport and folding of newly synthesized proteins and maintains ER stress signaling proteins in inactive forms at the ER membrane. Accumulation of damaged proteins in the ER results in dissociation of GRP78, allowing the release and activation of ER stress signaling proteins, and transcription of UPR target genes [40, 41]. In addition, prolonged ER stress results in the expression of CHOP, a transcription factor whose expression contributes to cell death in the late stages of ER stress [42, 43]. Increased mRNA and protein expression of GRP78 and CHOP following exposure to 689534/Cu2+ supported an active UPR. Furthermore, the ability of cycloheximide to inhibit NSC 689534/Cu2+-associated cell death suggests that ER stress plays a crucial role in this agent’s mechanism. An additional consequence of chronic oxidative stress is induction of autophagy [44]. Autophagy is a process by which bulk cytoplasmic components including organelles and cytosolic proteins are sequestered into vesicles known as autophagosomes, which fuse with lysosomes where their contents are degraded. Historically, autophagy has been regarded as a cytoprotective process, however autophagy has subsequently been shown to cause cell death via multiple mechanisms [45]. Surprisingly, while NSC 689534/Cu2+ induced autophagy in PC3 cells, our results indicate that the antiproliferative activity of NSC689534/Cu2+ was autophagy independent.

Next, we were encouraged to find that NSC 689534/Cu2+ yielded statistically significant tumor growth suppression in an HL60 xenograft model. Prior to this study, few reports had been published looking at the in vivo activity of copper thiosemicarbazones. In 1967 Crim et al. reported that a copper chelate form of a bis(thiosemicarbazone), KTS, showed in vivo activity in a Walker 256 carcinosarcoma in a rat model [46] while in 1976 Antholine et al. [47] reported that the Cu2+ liganded form of 2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazone was more active than the Fe2+ liganded form in preventing the growth of Ehrlich ascites tumor cells implanted into host mice.

Considerable mechanistic similarity exists between NSC 689534/Cu2+ and arsenic trioxide (As2O3), an agent that has been approved for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) [48]. Both molecules induce apoptosis through ROS in a process that is accompanied by the induction of ER-stress and autophagy [14, 49, 50]. Not surprisingly, both NSC 689534/Cu2+ and As2O3 deplete GSH [51] and synergize with BSO, implicating glutathione as an important resistance factor [52, 53]. Activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ against HL60 also fits the clinical spectrum of As2O3 (APL) given that both cell types are fast growing, have high rates of drug uptake and rapidly undergo apoptosis when challenged with oxidative stress. Preliminary data from our laboratory also suggests that, like As2O3, NSC 689534/Cu2+ appears to synergize with cisplatin (CI, 0.65) and bortezomib (CI, 0.47) [54–57]. Additionally, the combination of As2O3 and NSC 689534/Cu2+ also appears synergistic (CI, 0.55). As the therapeutic benefit of As2O3 alone versus hematological malignancies other than APL is limited, combination regimes are emerging as a means of increasing the spectrum of activity. For example, a Phase I/II study of multiple myeloma with a combination of As2O3/bortezomib/ascorbic acid yielded encouraging results [58]. As NSC689534/Cu2+ shows an ability to synergize effectively with several anti-cancer agents, it will be interesting to assess the spectrum of antitumor activity of NSC 689534/Cu2+ alone or in combination with other agents in vivo.

In conclusion, redox dysregulation is emerging as a specific vulnerability common to tumors. For example, overexpression of oncogenes such as Ras or c-Myc is associated with increased ROS production and reliance on endogenous anti-oxidants [59]. Here, we show that NSC 689534/Cu2+ is a potent anti-cancer therapeutic that mediates its effects through ROS generation, glutathione depletion, and ER stress induction. Promising in vivo activity combined with the ability of this agent to synergize with classical cancer therapeutics and mechanistic similarities with As2O3 supports further preclinical investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Ms. Sherry Yu. This project has been funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. This research was supported [in part] by the Developmental Therapeutics Program in the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis of the National Cancer Institute. NCI-Frederick is accredited by AAALACi and follows the Public Health Service Policy on the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animals used in this research project were cared for and used humanely according to the following policies: The U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Animals (1996); the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (1996); and the U.S. Government Principles for Utilization and Care of Vertebrate Animals Used in Testing, Research, and Training (1985).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yu Y, Kalinowski DS, Kovacevic Z, Siafakas AR, Jansson PJ, Stefani C, Lovejoy DB, Sharpe PC, Bernhardt PV, Richardson DR. Thiosemicarbazones from the old to new: iron chelators that are more than just ribonucleotide reductase inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5271–5294. doi: 10.1021/jm900552r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Y, Wong J, Lovejoy DB, Kalinowski DS, Richardson DR. Chelators at the cancer coalface: desferrioxamine to Triapine and beyond. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6876–6883. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wondrak GT. Redox-directed cancer therapeutics: molecular mechanisms and opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:3013–3069. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadler S, Makower D, Clairmont C, Lambert P, Fehn K, Sznol M. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor, 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone, administered by 96-hour intravenous continuous infusion. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1553–1563. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shao J, Zhou B, Zhu L, Qiu W, Yuan YC, Xi B, Yen Y. In vitro characterization of enzymatic properties and inhibition of the p53R2 subunit of human ribonucleotide reductase. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaston TB, Lovejoy DB, Watts RN, Richardson DR. Examination of the antiproliferative activity of iron chelators: multiple cellular targets and the different mechanism of action of triapine compared with desferrioxamine and the potent pyridoxal isonicotinoyl hydrazone analogue 311. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:402–414. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao J, Zhou B, Di Bilio AJ, Zhu L, Wang T, Qi C, Shih J, Yen Y. A Ferrous-Triapine complex mediates formation of reactive oxygen species that inactivate human ribonucleotide reductase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:586–592. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunos CA, Waggoner S, von Gruenigen V, Eldermire E, Pink J, Dowlati A, Kinsella TJ. Phase I Trial of Pelvic Radiation, Weekly Cisplatin, and 3-Aminopyridine-2-Carboxaldehyde Thiosemicarbazone (3-AP, NSC #663249) for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1298–1306. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saryan LA, Mailer K, Krishnamurti C, Antholine W, Petering DH. Interaction of 2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazonato copper (II) with Ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1981;30:1595–1604. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(81)90386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byrnes RW, Mohan M, Antholine WE, Xu RX, Petering DH. Oxidative stress induced by a copper-thiosemicarbazone complex. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7046–7053. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi N, Fujibayashi Y, Yonekura Y, Welch MJ, Waki A, Tsuchida T, Sadato N, Sugimoto K, Itoh H. Evaluation of 62Cu labeled diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) as a hypoxic tissue tracer in patients with lung cancer. Ann Nucl Med. 2000;14:323–328. doi: 10.1007/BF02988690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dehdashti F, Grigsby PW, Mintun MA, Lewis JS, Siegel BA, Welch MJ. Assessing tumor hypoxia in cervical cancer by positron emission tomography with 60Cu-ATSM: relationship to therapeutic response-a preliminary report. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;55:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04477-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Obata A, Kasamatsu S, Lewis JS, Furukawa T, Takamatsu S, Toyohara J, Asai T, Welch MJ, Adams SG, Saji H, Yonekura Y, Fujibayashi Y. Basic characterization of 64Cu-ATSM as a radiotherapy agent. Nucl Med Biol. 2005;32:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Platanias LC. Biological responses to arsenic compounds. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18583–18587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900003200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tisato F, Marzano C, Porchia M, Pellei M, Santini C. Copper in diseases and treatments, and copper-based anticancer strategies. Med Res Rev. 2009 doi: 10.1002/med.20174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stockwin LH, Bumke MA, Yu SX, Webb SP, Collins JR, Hollingshead MG, Newton DL. Proteomic analysis identifies oxidative stress induction by adaphostin. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3667–3681. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Decosterd LA, Cottin E, Chen X, Lejeune F, Mirimanoff RO, Biollaz J, Coucke PA. Simultaneous determination of deoxyribonucleoside in the presence of ribonucleoside triphosphates in human carcinoma cells by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1999;270:59–68. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arezzo F. Determination of ribonucleoside triphosphates and deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates in Novikoff hepatoma cells by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:57–64. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90613-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shvedova AA, Kommineni C, Jeffries BA, Castranova V, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Serbinova EA, Fabisiak JP, Kagan VE. Redox cycling of phenol induces oxidative stress in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:354–364. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00865.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malagoli D, Marchesini E, Ottaviani E. Lysosomes as the target of yessotoxin in invertebrate and vertebrate cell lines. Toxicol Lett. 2006;167:75–83. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plowman J, Dykes DJ, Jr, Hollingshead MG, Simpson-Herren L, Alley MC. Human Tumor Xenograft Models in NCI Drug Development. In: Teicher BA, editor. Anticancer Drug Development Guide: Preclinical Screening, clinical Trials and Approval. totowa, NJ: Humana; 1997. pp. 101–125. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antholine W, Knight J, Whelan H, Petering DH. Studies of the reaction of 2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazone and its iron and copper complexes with biological systems. Mol Pharmacol. 1977;13:89–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gómez-Saiz P, G-G R, Maestro M, Luis Pizarro J, Isabel Arriortua M, Lezama L, Rojo T, García-Tojal J. Unexpected Behaviour of Pyridine-2-carbaldehyde Thiosemicarbazonatocopper(II) Entities in Aqueous Basic Medium - Partial Transformation of Thioamide into Nitrile. European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 2005:3409–3413. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finch RA, Liu MC, Cory AH, Cory JG, Sartorelli AC. Triapine (3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone; 3-AP): an inhibitor of ribonucleotide reductase with antineoplastic activity. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1999;39:3–12. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2571(98)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cory JG, Cory AH, Rappa G, Lorico A, Liu MC, Lin TS, Sartorelli AC. Inhibitors of ribonucleotide reductase. Comparative effects of amino- and hydroxy-substituted pyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994;48:335–344. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90105-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krakoff IH, Brown NC, Reichard P. Inhibition of ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase by hydroxyurea. Cancer Res. 1968;28:1559–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paglin S, Hollister T, Delohery T, Hackett N, McMahill M, Sphicas E, Domingo D, Yahalom J. A novel response of cancer cells to radiation involves autophagy and formation of acidic vesicles. Cancer Res. 2001;61:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tasdemir E, Galluzzi L, Maiuri MC, Criollo A, Vitale I, Hangen E, Modjtahedi N, Kroemer G. Methods for assessing autophagy and autophagic cell death. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;445:29–76. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-157-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bampton ET, Goemans CG, Niranjan D, Mizushima N, Tolkovsky AM. The dynamics of autophagy visualized in live cells: from autophagosome formation to fusion with endo/lysosomes. Autophagy. 2005;1:23–36. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuervo AM. Autophagy: in sickness and in health. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 2007;3:542–545. doi: 10.4161/auto.4600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fels DR, Ye J, Segan AT, Kridel SJ, Spiotto M, Olson M, Koong AC, Koumenis C. Preferential cytotoxicity of bortezomib toward hypoxic tumor cells via overactivation of endoplasmic reticulum stress pathways. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9323–9330. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Tojal J, Garcia-Orad A, Diaz AA, Serra JL, Urtiaga MK, Arriortua MI, Rojo T. Biological activity of complexes derived from pyridine-2-carbaldehyde thiosemicarbazone. Structure of. J Inorg Biochem. 2001;84:271–278. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(01)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sartorelli AC. Effect of chelating agents upon the synthesis of nucleic acids and protein: inhibition of DNA synthesis by 1-formylisoquinoline thiosemicarbazone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1967;27:26–32. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(67)80034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sartorelli AC, Agrawal KC, Tsiftsoglou AS, Moore EC. Characterization of the biochemical mechanism of action of alpha-(N)-heterocyclic carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazones. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1976;15:117–139. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(77)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tardito S, Isella C, Medico E, Marchio L, Bevilacqua E, Hatzoglou M, Bussolati O, Franchi-Gazzola R. The thioxotriazole copper(II) complex A0 induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and paraptotic death in human cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24306–24319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mori K. Tripartite management of unfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell. 2000;101:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harding HP, Calfon M, Urano F, Novoa I, Ron D. Transcriptional and translational control in the Mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.011402.160624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaufman RJ. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1389–1398. doi: 10.1172/JCI16886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1249–1259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin S, White E. Tumor suppression by autophagy through the management of metabolic stress. Autophagy. 2008;4:563–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Y, Singh R, Massey AC, Kane SS, Kaushik S, Grant T, Xiang Y, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Loss of macroautophagy promotes or prevents fibroblast apoptosis depending on the death stimulus. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4766–4777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706666200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Crim JA, Petering HG. The antitumor activity of Cu(II)KTS, the copper (II) chelate of 3-ethoxy-2-oxobutyraldehyde bis(thiosemicarbazone) Cancer Res. 1967;27:1278–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antholine WE, Knight JM, Petering DH. Inhibition of tumor cell transplantability by iron and copper complexes of 5-substituted 2-formylpyridine thiosemicarbazones. J Med Chem. 1976;19:339–341. doi: 10.1021/jm00224a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tallman MS. The expanding role of arsenic in acute promyelocytic leukemia. Semin Hematol. 2008;45:S25–S29. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kanzawa T, Zhang L, Xiao L, Germano IM, Kondo Y, Kondo S. Arsenic trioxide induces autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by upregulation of mitochondrial cell death protein BNIP3. Oncogene. 2005;24:980–991. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Du Y, Wang K, Fang H, Li J, Xiao D, Zheng P, Chen Y, Fan H, Pan X, Zhao C, Zhang Q, Imbeaud S, Graudens E, Eveno E, Auffray C, Chen S, Chen Z, Zhang J. Coordination of intrinsic, extrinsic, and endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis by imatinib mesylate combined with arsenic trioxide in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:1582–1590. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li JJ, Tang Q, Li Y, Hu BR, Ming ZY, Fu Q, Qian JQ, Xiang JZ. Role of oxidative stress in the apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma induced by combination of arsenic trioxide and ascorbic acid. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2006;27:1078–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Han YH, Kim SZ, Kim SH, Park WH. Induction of apoptosis in arsenic trioxide-treated lung cancer A549 cells by buthionine sulfoximine. Mol Cells. 2008;26:158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fruehauf JP, Trapp V. Reactive oxygen species: an Achilles' heel of melanoma? Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:1751–1757. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.11.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang N, Wu ZM, McGowan E, Shi J, Hong ZB, Ding CW, Xia P, Di W. Arsenic trioxide and cisplatin synergism increase cytotoxicity in human ovarian cancer cells: Therapeutic potential for ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li H, Zhu X, Zhang Y, Xiang J, Chen H. Arsenic trioxide exerts synergistic effects with cisplatin on non-small cell lung cancer cells via apoptosis induction. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:110. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Campbell RA, Sanchez E, Steinberg JA, Baritaki S, Gordon M, Wang C, Shalitin D, Chen H, Pang S, Bonavida B, Said J, Berenson JR. Antimyeloma effects of arsenic trioxide are enhanced by melphalan, bortezomib and ascorbic acid. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:467–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan H, Wang YC, Li D, Wang Y, Liu W, Wu YL, Chen GQ. Arsenic trioxide and proteasome inhibitor bortezomib synergistically induce apoptosis in leukemic cells: the role of protein kinase Cdelta. Leukemia. 2007;21:1488–1495. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berenson JR, Matous J, Swift RA, Mapes R, Morrison B, Yeh HS. A phase I/II study of arsenic trioxide/bortezomib/ascorbic acid combination therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1762–1768. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.