Abstract

Cyclopentenone prostaglandins (CyPGs), such as 15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2), are active prostaglandin metabolites exerting a variety of biological effects that may be important in the pathogenesis of neurological diseases. Ubiquitin-C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) is a brain specific deubiquitinating enzyme whose aberrant function has been linked to neurodegenerative disorders. We report that [15d-PGJ2] detected by quadrapole mass spectrometry (MS) increases in rat brain after temporary focal ischemia, and that treatment with 15d-PGJ2 induces accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and exacerbates cell death in normoxic and hypoxic primary neurons. 15d-PGJ2 covalently modifies UCH-L1 and inhibits its hydrolase activity. Pharmacologic inhibition of UCH-L1 exacerbates hypoxic neuronal death while transduction with a TAT-UCH-L1 fusion protein protects neurons from hypoxia. These studies indicate UCH-L1 function is important in hypoxic neuronal death and excessive production of CyPGs after stroke may exacerbate ischemic injury by modification and inhibition of UCH-L1.

Keywords: Ubiquitin proteasome pathway, Ubiquitin-C-terminal hydrolase L1, Cyclopentenone prostaglandins, Protein post-translational modification, Arachidonic acid, Hypoxic neuronal injury

Introduction

Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is induced after cerebral ischemia and exacerbates ischemic neuronal injury through a variety of mechanisms (Nakayama et al 1998). PGD2, the major COX-2 product synthesized in the central nervous system, is dehydrated to generate biologically active cyclopentenone prostaglandins (CyPGs) of the J2 series, including PGJ2, Δ12-PGJ2 and 15-deoxy- Δ12,14-PGJ2 (15d-PGJ2) (Uchida and Shibata 2008). These CyPGs are characterized by the presence of a cyclopentenone ring which can directly modify nucleophiles such as free sulfhydryls in cysteine residues of cellular proteins. While CyPGs can covalently modify cysteines in a large number of proteins, CyPGs are thought to play specific signal transduction roles by high affinity interactions with specific proteins such as PPARγ, and regulate cell proliferation and lipid metabolism (Kliewer et al 1995; Shiraki et al 2005). However, 15d-PGJ2 can also modify many other cellular proteins, and therefore has many PPARγ independent effects including protein turnover inhibition, inducing cytoskeletal dysfunction and apoptosis (Ogburn and Figueiredo-Pereira 2006; Shibata et al 2003b; Stamatakis et al 2006). These PPARγ independent effects of CyPGs may include disruption of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (UPP) (Li et al 2004b).

The UPP is responsible for the degradation of mutant or misfolded proteins in cells and plays a critical role in maintaining cell homeostasis (Vernace et al 2007). Interruption of UPP function results in the accumulation and aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins (Ub-proteins) in cells, which are the pathological hallmark of some neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson's disease (PD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD) (Giasson and Lee 2003; Oddo 2008). Ub-proteins also accumulate in neurons after global and focal cerebral ischemia (Ge et al 2007; Liu et al 2005), and the aggregation of Ub-proteins may contribute to cell stress following ischemia, thereby amplifying neuronal damage (Meller 2009). Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1), an important component of the neuronal UPP, is selectively expressed in brain (Setsuie and Wada 2007). Inhibition of UCH-L1 activity induces the aggregation of Ub-proteins and enhances cell death in primary neurons (Li et al 2004b). UCH-L1 is a major oxidative damage target in brain and that it can be modified by a variety of reagents under different pathological conditions (Choi et al 2004). These post-translational modifications to UCH-L1 may substantially change its structure and function; thereby disrupting the UPP function and cell survival (Choi et al 2004; Kabuta et al 2008; Liu et al 2009; Meray and Lansbury 2007).

While modification of UCH-L1 has been implied in the pathogenesis of some neurodegenerative diseases, its role in ischemic neuronal injury is still largely unknown. The present study aims to detect the generation of CyPGs such as 15d-PGJ2 in brain after ischemia using highly specific MS methods. The effect of hypoxia on CyPG-protein adducts formation was determined in primary neurons using biotinylated arachidonic acid and PgD2. Modification of UCH-L1 by 15d-PGJ2 was studied in vitro and in intact primary neurons, and the effect of this modification on UCH-L1 activity and ischemic neuronal injury was assessed.

Materials and Methods

Animal studies were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Reagents and Antibodies

Free or biotinylated arachidonic acid and prostaglandins PGD2, PGE2, PGA1, 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14-prostaglandin D2 (15d-PGD2), 15d-PGJ2, and 9,10-dihydro-15-deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 (CAY10410) were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI); Anti-UCH-L1 antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO); monoclonal anti-ubiquitin, anti-6-His and anti-HA antibodies were from Covance (Berkeley, CA); anti-GAPDH antibody was from Ambion (Austin, TX), while Cy3-conjugated monoclonal mouse anti-biotin and Alexafluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson Immunoresearch Lab (West Grove, PA). Mouse monoclonal anti-mono- and poly ubiquitinated proteins antibody (clone FK2) was from Enzo Life Sciences (Plymouth Meeting, PA). LDN57444 was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, California) and ubiquitin AMC was from BostonBiochem (Cambridge, MA). Protein A/G beads, NeutrAvidin beads and HRP-conjugated streptavidin (streptavidin-HRP) were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). UPLC organic solvents and water were from VWR (West Chester, PA). Anti-β-actin antibody and all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

Plasmid constructs

The DNA sequence encoding full-length rat UCH-L1 was amplified by PCR, and cloned into pET22b vector (Novagen, San Diego, CA). A UCH-L1 point mutation substituting serine for cysteine (C90S) was introduced by PCR. For recombinant transduction domain HIV-transactivator protein (TAT) tagged protein expression, rat UCH-L1 wild type (WT) and mutant UCH-L1 C90S sequences were cloned into a modified pET30a vector (provided by Drs. Jun Chen and Guodong Cao, University of Pittsburgh) containing the N-terminus TAT and HA sequences (Cao et al 2002). Constructs were confirmed by sequencing.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant proteins

Plasmids were introduced into Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) strains (Novagen, San Diego, CA) producing 6× His-tagged full length UCH-L1 or its mutant proteins. Protein production was induced by shaking the E.Coli Rosetta cells in “overnight express autoinduction system” (Novagen, San Diego, CA) at 300 rpm for 16h, then purified with a His-select column (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein purity was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. Recombinant UCH-L1 protein was further confirmed by Western blot. Similar procedures were performed for expression and purification of TAT fusion proteins.

Adenovirus vector construction and generation

Adenoviruses containing mouse Wild Type COX-2 (AdV- COX-2) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (AdV-EGFP) sequences were constructed, propagated, and titered as described previously (Li et al 2010). Recombinant adenoviruses were generated by homologous recombination in HEK 293 cells expressing Cre recombinase (CRE8 cells) after cotransfection of DNA with an adenovirus 5-derived, E1- and E3-deleted adenoviral backbone (psi5) and pAdlox. The inserted cDNA expression was under the control of a human CMV promoter.

Cortical Primary neuronal culture

Cortical primary neuronal cultures were prepared from E17 fetal rats (Sprague-Dawley, Charles River, Wilmington, MA) as previously described (Li et al 2008) and used for experiments after 9 days. Cells were grown in serum-free Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with B27 and GlutaMAX (Invitrogen).

In vitro hypoxia and cell death measurements

Hypoxia was performed using a hypoxic glove box (Coy Laboratories, Grass Lake, MI) flushed with 92% argon, 5% CO2 and 3% H2 for 2-3 hours as described previously (Li et al 2008) resulting in ∼40% cell death after 24h reperfusion. Staurosporin (20 μM, a 100% cell death internal standard) and 1μM MK801 (a 100% cell survival internal standard) treatments were included in each cell death assay experiment. Cell death and cell viability were quantitatively assessed by measuring LDH release into the culture medium 48h after hypoxia or indirectly through the MTT cell viability assay. Cell death was also measured by staining cells with 0.1μg/ml propidium iodide (PI) plus 0.1μg/ml Hoechst and fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS 24h after hypoxia. PI and Hoechst -stained cells were counted by a blinded observer from 10-12 fields of at least three cultures with a fluorescence microscope. Apoptotic cells were detected by TUNEL staining following manufacturer's directions (Apoptag Plus, Millipore, Billerica, MA). In brief, neurons were seeded on the coverslips and incubated with 20μM of 15d-PGJ2, 15d-PGD2, CAY10410 or vehicle together under hypoxic or normoxic conditions. Cells were fixed 24h later with 1% paraformaldehyde and ethanol:acetic acid (2:1, V:V). DNA fragments were labeled with the digoxigenin-nucleotide and detected by an fluorescein conjugated anti-digoxigenin antibody. TUNEL-positive cells undergoing apoptosis were counted as well as cells with normal rounded nuclear morphology as a measure of live cells. Data are expressed as percentage total cells.

In vitro binding assay

Purified recombinant UCH-L1 protein (1 μg, ∼0.4μM) was incubated with 1μM or 10μM biotinylated (b-) 15d-PGJ2 or vehicle for 1h in 100μl of binding buffer (20mM Tris, pH7.0; 45mM NaCl; 5mM MgCl2; 0.1mM DTT, 1% glycerol) before immunoblotting. For the competition binding assay, UCH-L1 protein was pre-incubated with 500μM of 15d-PGJ2, CAY10410 or vehicle for 30min at room temperature (RT) before adding 5μM b-15d-PGJ2.

Avidin pull-down assay

The avidin pull-down assay was performed as previously described (Stamatakis et al 2006). Primary neurons were incubated with 10μM 15d-PGJ2 or b-15d-PGJ2 for 2h before harvest. Equal amounts of proteins were incubated with NeutrAvidin beads for 4 h at 4 °C. Bound proteins were washed three times with lysis buffer (50mM Tris, pH7.4; 150mM NaCl; 1mM EDTA; 1% Triton X-100) before elution and detected by Western blot.

Immunoprecipitation

Primary neurons were treated with 10μM 15d-PGJ2 or b-15d-PGJ2 for 2h before harvesting. Cell lysates were precipitated using polyclonal anti-UCH-L1 antibody or control IgG at 4°C overnight before incubation with protein A/G beads. Immunoprecipitates were washed with lysis buffer (50mM Tris, pH7.4; 150mM NaCl; 1mM EDTA; 1% Triton X-100), eluted and immunoblotted.

Fluorescent immunocytochemistry

Fluorescent immunocytochemical staining was performed as previously described (Colgan et al 2007). Primary neurons were seeded on glass coverslips and incubated with 15d-PGJ2 or methyl acetate (veh) for 24h before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Cells were stained with anti-Ub-protein antibody and Alexafluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody. Coverslips were mounted on slides with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI and confocal images were acquired with a FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). For UCH-L1 and 15d-PGJ2 localization, primary neurons were treated with b-15d-PGJ2 for 2h before fixation then double stained with anti-UCH-L1 and Cy3-conjugated anti-biotin antibodies.

In vitro hydrolase activity assay

The UCH-L1 hydrolase activity assay was performed as previously described with slight modifications (Liu et al 2002). Briefly, 2 μM UCH-L1 protein was incubated with various concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 or vehicle for 2h before dilution with UCH hydrolase buffer (50mM Tris, pH7.6; 0.5mM EDTA, 0.1mg/ml ovalbumin, 5mM DTT). Samples were then mixed with 500nM ubiquitin-AMC. The final concentration for UCH-L1 was 100nM. Free AMC fluorophore was read using a fluorescence plate reader (ex 360nm, em 460 nm). UCH-L1 C90S mutant protein (100 nM) lacking hydrolase activity (Gong et al 2006) was included as a negative control.

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO)

MCAO was performed as previously described (Ahmad et al 2009) for a duration of 90 min. A silicone coated 4.0 nylon filament was advanced 17mm into the internal carotid artery from the bifurcation of internal carotid artery and external carotid artery. Sham surgeries were performed identically without insertion of suture. 24 h after reperfusion, rats were sacrificed and their brains were processed for CyPG measurement.

Capillary LC ESI-TOF MS analysis

UCH-L1 and 15d-PGJ2 modified UCH-L1 was analyzed using capillary LC ESI-TOF MS. UCH-L1 protein was incubated with 15d-PGJ2, arachidonic acid, PGD2 or methyl acetate (vehicle) in 1XPBS at RT for 2h. Samples were diluted in 25mM ammonium bicarbonate before loading on the C4 precolumn (Acclaim PepMap300 C4, 5μm, 300A, 300μm i.d. × 5 mm, Dionex) of the LC system (Ultimate 3000, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA). The LC system was directly coupled to an electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (micrOTOF, BrukerDaltonics, Billerica, MA). Desalting was performed with 2.5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid followed by elution with 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid. Mass spectra were acquired in positive ion mode over the mass range m/z 500 to 3000. ESI spectra were deconvoluted to obtain molecular ion masses with DataAnalysis 3.3 (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA).

Measurement of 15d-PGJ2 in rat brain

15d-PGJ2 was measured by quadrupole liquid MS as previously described (Miller et al 2009). Samples were homogenized in 0.12 M potassium phosphate buffer (5mM MgCl2 and 0.113 mM BHT) and centrifuged. The supernatant was removed and 7.5 ng of deuterated 15d-PGD2 was used as the internal standard. Samples were loaded onto Oasis HLB solid phase extraction cartridges (Waters, Acquity, Milford, MA) and washed with 1 ml volumes of 5% methanol before elution with 100% methanol. Extracts were dried under nitrogen and reconstituted in 125 μL of 80:20 methanol:de-ionized water. 15d-PGJ2 was separated via reverse phase UPLC with a Acquity UPLC BEH C18 1.7μM, 2.1 × 100 mm column. MS analysis was performed via a Thermo TSQ Quantum Ultra triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). MRM transition of m/z was 316.1 to 272 with a collision energy of 13 eV and a scan time 0.01 seconds. Parameters were optimized to obtain the highest [M-H]+ ion abundance. Data was acquired using Xcalibur Software version 2.0.6.

Statistical analysis

15d-PGJ2 concentrations were analyzed using Student's T test; all other data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA to calculate differences between groups. Results were considered to be significant when p < 0.05.

Results

15d- PGJ2 concentration is increased in rat brain after temporary focal ischemia

The triple quadrupole MS/MS daughter ions of 15d-PGJ2 were identified and used to quantify 15d-PGJ2 concentration in rat brain via selected reaction monitoring. 15d-PGJ2 produced a unique MS/MS fragmentation pattern that includes an abundant parent ion at m/z 316 (Fig 1A) and a major daughter ion at m/z 271. 15d-PGJ2 was quantified by selective reaction monitoring of the m/z 271 fragment of the 316 m/z parent 15d-PGJ2 ion. Additional selectivity was afforded by ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) separation of 15d-PGJ2, eluting at 3.1 minutes as determined from reference standards. Brain tissue extracts from sham surgery and MCAO animals demonstrated that free endogenous 15d-PGJ2 was below detection limits in sham surgery brain but was quantifiable in ischemic hemisphere 24 h after 90 min of middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), at concentrations of 23.72 ± 6.48 nM (Fig 1B).

Figure 1. [15-deoxy-Δ12,14-PGJ2(15d-PGJ2)] in rat brain after middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO).

A. MS/MS fragmentation pattern of 15d-PGJ2 authentic standard with a Parent Mass (m/z) of 316. The prevalent 271m/z daughter Ion was used to quantify 15d-PGJ2 using quadrupole MS/MS with selective reaction monitoring. Arrow (inset) indicates fragmentation point of parent ion. B. 15d-PGJ2 concentration in rat brain hemisphere 24h after 90 minutes MCAO. Data are expressed as means +/- SE. *P < .05. n=4-6.

15d-PGJ2 increases ubiquitinated protein accumulation and induces neuronal cell death

Treatment of primary neurons with 15d-PGJ2 resulted in a dose dependent increase in the accumulation of Ub-proteins compared to vehicle controls (Fig 2A, left). The distribution of Ub-proteins in the neuron was altered 24h after incubation with 15d-PGJ2 as detected by fluorescent immunocytochemistry: Ub-proteins were distributed evenly throughout the cytoplasm and were seen as small discrete punctate structures in control neurons, while large perinuclear aggregates containing Ub-proteins were frequently observed in neurons treated with 20μM 15d-PGJ2 (Fig 2A, right). Thus,15d-PGJ2 treatment interferes with the UPP's function in primary neurons.

Figure 2. Effect of treatment with 15d-PGJ2 upon accumulation of Ub-proteins and cell death in primary neuronal culture.

A. left: Primary neurons were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 for 24h then harvested. Ub-proteins were detected by IB with anti-ubiquitin antibody. β-actin served as a loading control. right: representative confocal images (240×) of primary neurons after incubation with vehicle (veh) or 20 μM 15d-PGJ2 for 24h prior to staining with anti-ubiquitinated protein antibody paired with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green) and DAPI (blue). B. Primary neurons were incubated with vehicle or 15d-PGJ2 for 1 h prior to normoxia (a,b) or hypoxia (c,d). Cell death was measured using LDH (a,c) and MTT (b,c) methods. n = 6 wells per group. * P < 0.02. C. left: Primary neurons were incubated with vehicle, CAY10410 or 15d-PGD2 for 24h prior to harvest. Ub-proteins were detected by IB with anti-ubiquitin antibody. n= 6 per group. right: Primary neurons were treated with CAY10410 or 15d-PGD2 1 h prior to hypoxia. Cell death was measured using the LDH method. D: Primary neurons were incubated with vehicle, 15d-PGJ2 or CAY10410 (20 μM) for 24h prior to hypoxia or normoxia treatment. 24 h later, cells were stained with propidium iodide (PI) and Hoechst. a: PI-positive cells were counted and cell death was calculated as percent total cells (Hoechst). n = 10 – 12 per group. b: representative photos of Hoechst and PI-Hoechst overlay stained cells. Single arrows indicate representative cells with apoptotic morphology; double arrows are representative cells exhibiting rounded morphology. c: Percentage cells with normal morphology in normoxic (top) and hypoxic (bottom) groups treated with 20 μM of 15d-PGJ2, 15d-PGD2, CAY10410 or vehicle. * P < 0.001; ** < 0.01; # < .05; NS: not significant. Data are expressed as means +/- SE. IB: immunoblot; MK: 1 μM MK801; SP: 20 μM staurosporin; Ub-Proteins: Ubiquitinated proteins; Veh: vehicle.

To test whether 15d-PGJ2 treatment exacerbates hypoxic neuronal cell death, primary neurons were pre-incubated with 15d-PGJ2 for 1h before hypoxia. Cell death was measured 48h after hypoxia. 15d-PGJ2 exacerbated hypoxic neuronal cell death (Fig. 2B) in a dose dependent manner with 20μM 15d-PGJ2 treatment significantly increasing cell death. 15d-PGJ2 treatment also induced primary neuronal cell death under normoxic conditions. There was a significant increase in the percentage of PI stained cells in 15d-PGJ2 treated cells as compared to vehicle controls (Fig 2D) further supporting that incubation with 20 μM 15d-PGJ2 increases cell death under both hypoxic and normoxic conditions.

The above data indicate that 15d-PGJ2 impairs the UPP's function and exacerbates cell death in primary neurons. To test whether these effects are mediated through a PPARγ dependent mechanism, two analogs of 15d-PGJ2, CAY10410 (CAY) and 15-deoxy-Δ12, 14-prostaglandin D2 (15d-PGD2), were used to treat primary neurons. CAY10410 has a similar structure to 15d-PGJ2 but lacks the reactive cyclopentenone ring, retaining PPARγ ligand activity (Shibata et al 2003a); 15d-PGD2 does not have the cyclopentenone ring structure nor can it activate PPARγ. Primary neurons were incubated with CAY10410 or 15d-PGD2 at the indicated concentrations for 24h, Ub-proteins were detected (Fig 2C, left) and cell death was measured (Fig 2C, right). In contrast to 15d-PGJ2, neither CAY10410 nor 15d-PGD2 treatment increased Ub-protein accumulation or exacerbated hypoxic neuronal cell death. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the percentage of PI stained cells in 20μM CAY10410 treated cells compared to vehicle control under hypoxic or normoxic conditions (Fig 2D, a-b). 15d-PGJ2-treated, but not 15d-PGD2- or CAY10410- treated cultures had a significantly lower percentage of cells with normal nuclear morphology as determined by DAPI staining compared to vehicle controls (Fig 2D,c). In the TUNEL assay, 15d-PGJ2 – treated normoxic cultures had significantly more TUNEL-positive cells compared to vehicle controls (22.7±2.2% vs 12.7±1.0%, P<.05); there was no increase in TUNEL-positive cell percentage when treated with CAY10410 or 15d-PGD2. No significant difference in TUNEL staining was observed in hypoxic cells between any of the treatment groups. 15d-PGJ2 induces predominantly PI- rather than TUNEL staining in neurons, particularly after hypoxia, consistent with a primarily necrotic mechanism of cell death. These results demonstrate that 15d-PGJ2 impairs the neuronal UPP and exacerbates neuronal death through a PPARγ independent and cyclopentenone ring dependent mechanism.

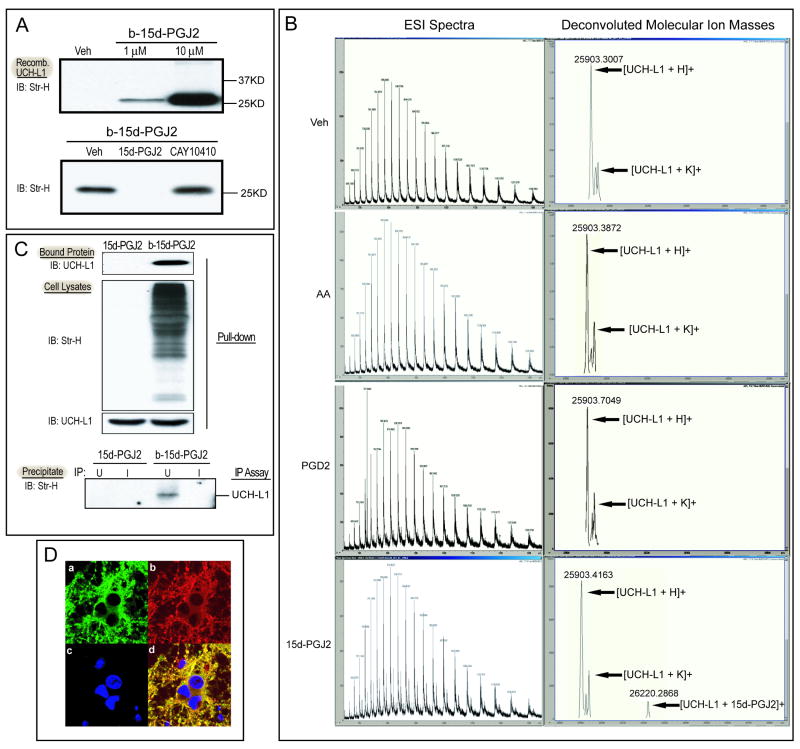

15d-PGJ2 covalently modifies UCH-L1 in vitro and in intact primary neurons

UCH-L1 is a brain specific protein that plays an important role in the neuronal UPP as a deubiquitinating enzyme (Setsuie and Wada 2007). Its modification and malfunction is associated with the accumulation of Ub-proteins and cell death in neurons. Because CyPGs modify protein cysteine residues through Michael additions, and UCH-L1 contains 6 cysteine residues, it is possible UCH-L1 could be directly modified by 15d- PGJ2. To test this hypothesis, we first performed an in vitro binding assay using recombinant UCH-L1 protein and biotinylated 15d-PGJ2 (b-15d-PGJ2). Recombinant UCH-L1 protein (1 μg) was incubated with 1μM or 10μM b-15d-PGJ2 or vehicle (Veh) for 1 hour. Biotin signals were detected with immunoblotting and streptavidin-HRP. A band representing the b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 adduct was detected and increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3A, top). Binding specificity was further assessed using a competition assay. UCH-L1 was incubated with 100 fold excess unlabeled 15d-PGJ2 or its analog, CAY10410, for 30 min before b-15d-PGJ2 was added. As shown in Fig 3A (bottom), the b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 band was greatly attenuated after incubation with excess unlabeled 15d-PGJ2 but not CAY10410. Taken together, these results indicate that 15d-PGJ2 directly modifies UCH-L1, and the reactive α,β-unsaturated carbon in the cyclopentenone ring is required for this protein modification.

Figure 3. Covalent modification of UCH-L1 by 15d-PGJ2 in vitro and in primary neurons.

A. upper: Recombinant UCH-L1 protein (1 μg) was incubated with biotinylated (b-) 15d-PGJ2 or vehicle (ethanol, Veh) for 2h. b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 adducts were detected by immunoblotting with streptavidin-HRP (Str-H). lower: Recombinant UCH-L1 protein (1 μg) was preincubated with methyl acetate (Veh), 500 μM 15d-PGJ2 or CAY10410 for 30 min before incubation with 5 μM b-15d-PGJ2 and b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 adduct in each reaction were detected. B. Capillary LC ESI-TOF MS analysis of UCH-L1 incubated with Vehicle (Veh), arachidonic acid (AA), PGD2 and 15d-PGJ2. Charge state distribution (left) and deconvoluted molecular ion mass spectra (right) are shown. C. Primary neurons were incubated with 10 μM 15d-PGJ2 or b-15d-PGJ2 for 2h before harvest. The b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 adducts in cell lysates were detected after Avidin pull-down or immunoprecipitation assays. Top: Avidin pull-down assay: Proteins bound to NeutrAvidin beads were separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted with anti-UCH-L1 antibody. Center: Immunoblots of cell lysates probed with Streptavidin-HRP (Str-H) and anti-UCH-L1 antibody. Bottom: IP assay: Primary neuron cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-UCH-L1 antibody (U) or control IgG (I) and protein A/G beads. Immunoprecipitates were separated and probed with Streptavidin-HRP to detect b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 adducts. D. Immunocytochemical staining of primary neurons after 2h incubation with 10μM b-15d-PGJ2. Representative photos of: a) endogenous UCHL-1 distribution using FITC conjugated anti-UCHL-1 antibody. b) b-15d-PGJ2 distribution using Cy3 conjugated anti-biotin antibody. c) DAPI staining of nuclei. d) Merged picture. Photos at 60×. IB: Immunoblot; IP: immunoprecipitation.

Next, ESI-MS analysis was performed on recombinant UCH-L1 incubated with 15d-PGJ2. As shown in Fig 3B, the mass detected for free UCH-L1 is 25903 Da, whereas incubation of UCH-L1 with 15d-PGJ2 at a 1:1 ratio results in a second peak at 26220 Da, corresponding to the incorporation of one 15d-PGJ2 molecule into the UCH-L1 protein. However, incubation of UCH-L1 with arachidonic acid or other prostaglandins lacking a cyclopentenone ring structure, including PGD2 and 15d-PGD2 (data not shown), only resulted in a single peak of 25903 Da, the same as free UCH-L1. These results further support that UCH-L1 is directly modified by 15d-PGJ2.

To test whether endogenous UCH-L1 in intact neurons is modified by 15d-PGJ2 in the presence of other cellular proteins, we incubated primary neurons with either 15d-PGJ2 or b-15d-PGJ2 for 2 hours followed by avidin pull-down and immunoprecipitation assays. Cell lysates were incubated with NeutrAvidin beads, and biotinylated proteins bound to NeutrAvidin beads were then eluted and immunoblotted. As shown in Fig 3C (top), UCH-L1 was detected in the pull-down eluent only of the b-15d-PGJ2 treated group, whereas it could be detected in the cell lysates of both groups (Fig 3C, center). Using an immunoprecipitation assay, the b-15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 complex was precipitated by an anti-UCH-L1 antibody (U) and protein A/G beads using normal rabbit IgG (I) as a negative control. The complex was eluted and detected with streptavidin-HRP by Western blot. A band with the expected molecular weight was detected only in the b-15d-PGJ2 treated group (bottom, Fig 3C), confirming that direct interaction between b-15d-PGJ2 and endogenous UCH-L1 occurs within the intact neuron.

Colocalization of 15d-PGJ2 and endogenous UCH-L1 within the cell is shown in Fig 3D. Both UCH-L1 (a) and 15d-PGJ2 (b) were primarily located in the cytoplasm and neurites, and to a lesser extent, in the peri-nuclear region in b-15d-PGJ2-incubated neurons. 15d-PGJ2 extensively co-localized with UCH-L1 (d).

15d-PGJ2 modification inhibits UCH-L1 hydrolase activity

As a deubiquitinating enzyme, UCH-L1 has hydrolase activity which cleaves ubiquitin from ubiquitinated peptides for later reuse. To test whether 15d-PGJ2 modification interferes with UCH-L1 hydrolase activity, an in vitro hydrolase activity assay was performed using ubiquitin-AMC, a substrate that fluoresces when hydrolyzed by UCH-L1. Recombinant UCH-L1 was incubated with 15d-PGJ2, CAY10410, or vehicle and fluorogenic AMC was detected by spectrofluorometry after cleavage from the ubiquitin-AMC molecule. Incubation with 0.5 μM 15d-PGJ2 significantly decreased the rate of UCH-L1 hydrolysis of ubiquitin-AMC compared to vehicle control (Fig 4); furthermore, incubation with 12.5 μM 15d-PGJ2 reduced hydrolase activity to that of inactive mutant UCH-L1 C90S protein. However, incubation with CAY10410 had no inhibitory effect on UCH-L1 hydrolase activity. Incubation of ubiquitin-AMC with free 15d-PGJ2 (without UCH-L1) as a negative control resulted in no detectable change in fluorescence (data not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that covalent modification of UCH-L1 by 15d-PGJ2 leads to significant loss of the enzyme's hydrolase activity.

Figure 4. Effect of 15d-PGJ2 on UCH-L1 hydrolase activity.

1μg of recombinant UCH-L1 was incubated with 15d-PGJ2, CAY10410 or vehicle (Veh, methyl acetate) at indicated concentrations. Hydrolase activity was measured using the fluorescent substrate ubiquitin-AMC. Fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units, λex=360nm and λem=460nm) produced by cleavage of ubiquitin-AMC was recorded at indicated time points. Mutant UCH-L1 C90S lacking hydrolase activity was included as a negative control. Data shown is the mean of the experiment with two replicates. Veh: vehicle; C90S: recombinant UCH-L1 C90S protein.

Impaired UCH-L1 hydrolase activity exacerbates hypoxic neuronal death, while delivery of UCH-L1 fusion protein protects against hypoxic injury

UCH-L1 dysfunction has been associated with the accumulation of Ub-proteins and cell death in neurons. However, its role in hypoxic neuronal injury is unclear. LDN 57444 (LDN), a specific and competitive ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase inhibitor with an IC50 of 0.88 μM for UCH-L1 and 25 μM for UCH-L3 (Liu et al 2003), was used to test the role of UCH-L1 activity in hypoxic injury. Primary neurons were incubated with 0.5-4 μM LDN or vehicle prior to hypoxia and cell death was determined. Incubation with LDN significantly exacerbated hypoxic neuronal death compared to vehicle control in a dose dependent manner (Fig 5A, right). However, incubation of primary neurons with 20μM LDN alone under normoxic conditions had no effect upon cell death (Fig 5A, left). Thus inhibition of endogenous UCH-L1 activity with LDN exacerbates hypoxic neuronal cell death suggesting that UCH-L1 hydrolase activity is important for cell survival under conditions such as hypoxia. Consistent with the cell death effect, treatment with LDN also increased accumulation of Ub-proteins in primary neurons after hypoxia, whereas the same treatment failed to show any significant change under normoxic conditions (Fig 5B). Thus, inhibition of UCH-L1 hydrolase activity with LDN impairs the UPP resulting in accumulation of Ub-proteins and exacerbates cell death in hypoxic neuronal cells.

Figure 5. Effect of UCH-L1 activity on hypoxic neuronal cell death and Ub-protein accumulation in primary neurons.

A. Primary neurons were treated with vehicle (DMSO), LDN 57444 or untreated for 1 hour, then underwent normoxia (left) or 3h hypoxia (right) then returned to normoxic conditions for 24h. Cell death was measured by LDH assay. N= 6 wells per group. Data are expressed as means +/- SE. * P < 0.01; ** < 0.05 vs vehicle treated group. B. Representative immunoblots of primary neuronal cell lysates (treated as in A) probed with anti-ubiquitin and anti-actin (loading control) antibodies. right: graphic illustration of western blot ubiquitinated protein lane densities expressed as % vehicle. n=3. * P < 0.05. C. top: Structure diagrams of HA-tagged wild type TAT-UCH-L1 WT and mutant TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion proteins. bottom left: TAT-UCH-L1 WT or mutant TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion proteins detected with immunoblots probed with anti-UCH-L1 antibody after incubation in primary neurons. (a-c, bottom right): Representative photos of immunocytochemical staining of fusion protein transduction in primary neurons after 1h incubation with 0.08μM of recombinant TAT-UCH-L1 WT, mutant TAT-UCH-L1 C90S proteins or PBS (UN) using anti-HA antibody (green) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue). D: Primary neurons were incubated with TAT-UCH-L1 WT, TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion proteins or vehicle for 1h prior to hypoxia. After hypoxia, cells were returned to normoxic conditions for 24h. Cell death was measured by assaying LDH released into the medium. N=6 per group. Data are expressed as means ± SE. * P < 0.01 versus vehicle-treated group. LDN: UCH-L1 inhibitor LDN 57444; Veh: vehicle; IB: immunoblot; WT: wild type TAT-UCH-L1; C90S: mutant TAT-UCH-L1 C90S; MK: MK801 1 μM; SP: staurosporin 20 μM; UN: untreated.

To further confirm that UCH-L1 activity protects against hypoxic neuronal injury, we constructed TAT-UCH-L1 wild type (WT) and mutant TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion proteins to transduce primary neurons. Both proteins contain a 6× His tag for purification and an HA tag for detection (Fig 5C, top). Construction and expression of the fusion proteins were confirmed by immunoblotting using both anti-UCH-L1 and anti-HA antibodies. A hydrolase activity assay performed using both TAT fusion proteins resulted in similar hydrolase activities to those of native recombinant UCH-L1 or UCH-L1-C90S proteins (data not shown). The ability of TAT fusion proteins to transduce primary neuronal cells was evaluated by immunoblotting and immunostaining primary neurons incubated with TAT-UCH-L1 WT and TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion proteins. TAT fusion proteins were detectable in cell lysates by immunoblotting (Fig 5C, bottom left). Immunostaining of primary neurons with an anti-HA antibody shows that TAT-UCH-L1 enters neurons at a transduction efficiency of about 80% (Fig 5C, bottom right). These data indicate that these TAT fusion proteins are biologically active and are able to transduce primary neurons.

To test the effect of overexpression UCH-L1 on hypoxic neuronal cell death, primary neurons were incubated with TAT-UCH-L1 WT or TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion proteins for 1h prior to hypoxia. Cell death was determined 24h post reperfusion. Incubation with TAT-UCH-L1 WT fusion protein significantly decreased hypoxic neuronal death in a dose dependent manner, whereas incubation with the inactive mutant, TAT-UCH-L1 C90S fusion protein had no effect on cell death as compared to vehicle control (Fig 5D). These data further support the hypothesis that UCH-L1 hydrolase activity is a significant determinant of hypoxic neuronal cell death.

Modification of UCH-L1 by arachidonic acid and PGD2 metabolites is increased after hypoxia in the primary neurons

To test whether arachidonic acid or its metabolites covalently modify endogenous proteins including UCH-L1 in primary neurons, primary neurons were incubated with biotinylated arachidonic acid or biotinylated prostaglandins PGD2, PGE2, 15d-PGJ2 or PGA1 under normoxic conditions for 2h. Biotinylated proteins in cell lysates were then detected by Western blot and were detected only in those neurons treated with biotinylated CyPGs 15d-PGJ2 and PGA1, but not in cells treated with biotinylated arachidonic acid or biotinylated prostaglandins lacking the cyclopentenone moiety such as PGD2 and PGE2 (Fig 6A). These data further support the necessity of the cyclopentenone ring for prostaglandin-protein modifications.

Figure 6. Modification of UCH-L1 and other proteins by arachidonic acid, prostaglandins and their metabolites in primary neurons.

A. Primary neurons were incubated with biotinylated arachidonic acid (AA), prostaglandins (PGD2 and PGE2), or CyPGs (15d-PGJ2 and PGA1) at indicated concentrations for 2h under normal culture conditions. Modified protein in the cell lysates were detected by streptavidin-HRP. B. Avidin pull-down assay detecting AA metabolite-modified UCH-L1 in primary neurons. Neurons were incubated with 20μM biotinylated AA and subjected to hypoxia (+) or normoxia (-) before harvest at the indicated time points. Top: NeutrAvidin bead bound UCH-L1 was detected by IB with anti-UCH-L1 antibody. Bottom: Biotinylated proteins and endogenous UCHL-L1 in neuronal lysates were detected by IB with streptavidin-HRP and anti-UCH-L1 antibody respectively. C. The effect of COX-2 overexpression on AA metabolite-modified protein accumulation in primary neurons. Neurons infected with AdV-COX-2, AdV-EGFP or vehicle (Veh) were incubated with 20μM biotinylated AA and subjected to hypoxia or normoxia. 3h after hypoxia/normoxia, cells were harvested and biotinylated proteins were detected by IB with streptavidin-HRP. D. The effect of COX-2 inhibition on AA metabolite-modified protein accumulation in primary neurons. Neurons were treated with rofecoxib (1μM) or vehicle (-) for 1h prior to incubation with 20μM biotinylated AA. Cells were harvested after hypoxia (+) or normoxia (-). Biotinylated proteins were detected by IB with streptavidin-HRP. E. Avidin pull-down assay to detect PGD2 metabolite-modified UCH-L1 in primary neurons. Neurons were incubated with 10μM biotinylated PGD2 and subjected to hypoxia (+) or normoxia (-). Cells were harvested 0 and 24h after hypoxia/normoxia. Upper three panels: Biotinylated proteins and endogenous UCH-L1 proteins in neuronal lysates were detected by IB with streptavidin-HRP (arrow at band indicating MW of UCH-L1) and anti-UCH-L1 antibody respectively. Bottom panel: NeutrAvidin bead-bound UCH-L1 was detected by IB with anti-UCH-L1 antibody. M: marker; AA: Arachidonic acid; UN: untreated cells; IB: immunoblot; AdV-COX-2: adenovirus containing mouse WT COX-2; AdV-EGFP: adenovirus containing EGFP.

Our in vivo data has shown that the concentration of 15d-PGJ2 significantly increased after brain ischemia (Fig1), indicating that 15d-PGJ2-UCH-L1 modification as well as other CyPG-protein modifications in neuronal cells might also increase after hypoxia. To test whether arachidonic acid metabolites increase protein modifications in hypoxic neurons, primary neurons were incubated with 20μM biotinylated arachidonic acid and subjected to hypoxic or normoxic conditions for 3h. Cell lysate immunoblots show a progressive increase in biotinylated proteins at 3h and 6h after hypoxia (Fig 6B, center), while UCH-L1 protein levels remain constant. Cell lysates were also incubated with NeutrAvidin beads and bound proteins were eluted and immunoblotted. A band corresponding to biotinylated UCH-L1 was detected in increasing intensity at 3 and 6 h after hypoxia, but not in normoxic samples (Fig 6B, top). Since arachidonic acid itself as well as other prostaglandins without a cyclopentenone ring can't modify UCH-L1 or other endogenous proteins directly, this increased formation of biotinylated UCH-L1 is likely due to the enhanced generation of CyPGs after hypoxia. Because the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins and CyPGs is COX-2 activity related, the amount of neuronal proteins modified by arachidonic acid metabolites in hypoxic neuronal cells should also be COX-2 activity related. To test this hypothesis, adenoviral vector containing the wild-type COX-2 gene sequence (AdV-COX-2) was used to overexpress the COX-2 protein in primary neurons. A similar adenoviral vector containing EGFP (AdV-EGFP) was used as control. 72h after infection, the neurons were incubated with 20μM biotinylated arachidonic acid and subjected to hypoxia or normoxia. Cells were harvested 3h after hypoxia and biotin incorporated proteins were detected (Fig. 5C). Consistent with the previous experiment, hypoxia enhanced biotin-protein adduct formation compared to normoxic neurons. Furthermore, higher levels of biotinylated protein accumulation were detected in the AdV-COX-2 infected neurons as compared to AdV-EGFP infected neurons or vehicle treated controls, suggesting that increased COX-2 activity enhances the formation of arachidonic acid metabolite-modified proteins in primary neurons. Additionally, the selective COX-2 inhibitor, rofecoxib, was applied to primary neurons prior to incubation with biotinylated arachidonic acid and hypoxia. Rofecoxib significantly reduced biotinylated protein formation in neurons harvested 3h after hypoxia (Fig 6D). These experiments show that arachidonic acid metabolites modify endogenous proteins including UCH-L1 in primary neurons and that the extent of this modification is increased after hypoxia in a COX-2 activity related manner.

PGD2 is the immediate precursor to CyPGs of the J2 series including 15d-PGJ2. Primary neurons were incubated with 10 μM biotinylated PGD2 under hypoxic or normoxic conditions (Fig 6E). Cells were harvested 0 and 24h after hypoxia and biotinylated proteins were detected. Biotinylated proteins were not detected at 0h in either group; however, they were detected 24h post treatment and more so in hypoxic neurons. Similarly, biotinylated UCH-L1, detected by anti-UCH-L1 antibody after pull down with NeutrAvidin beads, was not found in normoxic controls but was detected in cells harvested 24h after hypoxia (Fig 6E, bottom). These results suggest that UCH-L1 as well as other endogenous neuronal proteins are modified by PGD2 metabolites such as CyPGs of the J2 series, and that this modification is increased by hypoxia. Because hypoxia did not alter the expression of UCH-L1, the increased biotinylated UCH-L1 formation after hypoxia most likely is due to increased CyPGs metabolized from PGD2.

Discussion

A number of studies have demonstrated that CyPGs such as 15d-PGJ2 may modify important cellular proteins, including a number of proteins that regulate neuronal cell death and survival (Kondo et al 2002a; Kondo et al 2002b; Satoh and Lipton 2007; Uchida and Shibata 2008). Thus it has been proposed that CyPGs may play an important role in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders such as stroke, PD and AD (Milne et al 2005; Musiek et al 2006). However, the physiological relevance of CyPGs is uncertain since brain concentrations of CyPGs such as 15d-PGJ2 under these pathological conditions have not previously been determined.

Several groups have tried to detect endogenous 15d-PGJ2 and measure its concentration in vivo. Using an anti-15d-PGJ2 antibody and immunohistochemistry, Shibata reported the existence of endogenous 15d-PGJ2 both in macrophages and in motor neurons in spinal cords from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients (Shibata et al 2002). Antibody based Enzyme Immunoassay (EIA) was used by several groups to detect changes in 15d-PGJ2 levels under various pathological conditions. Restraint stress induces a COX-2-dependent increase of 15d-PGJ2 in rat brain cortex (Garcia-Bueno et al 2005) while cortical spreading depression induced by topical KCl also significantly increased 15d-PGJ2 levels in rat cerebrospinal fluid (Horiguchi et al 2006). Recently, Lin's group showed that Adv-COX1 infusion 72h before 50 min MCAO resulted in increased 15d-PGJ2 levels in rat brain ischemic tissues; however, 15d-PGJ2 levels in the uninfected control ischemic brain were not reported (Lin et al 2006). The above data all rely on antibody specificity, so the cross reactivity of the antibody for a number of structures closely related eicosanoid compounds such as PGJ2 and Δ12-PGJ2 is always a concern.

PGD2, the precursor of 15d-PGJ2, is the major COX-2 produced prostaglandin in the brain (Uchida and Shibata 2008). COX-2 expression and production of PGD2 is increased after ischemia (Li et al 2008; Nakayama et al 1998). Thus, one would expect that 15d-PGJ2 concentrations may be increased in brain after ischemia. To test this hypothesis, quadrupole liquid chromatography mass spectrometry was used to detect and quantify free endogenous 15d-PGJ2 in brain lysates from a focal cerebral ischemic model induced by 90 min of MCAO. Free endogenous 15d-PGJ2 was undetectable in normal rat brain, but was detected in ischemic hemispheres 24h after MCAO. To our knowledge, this is the first report confirming the presence and the increase of the endogenous CyPG 15d-PGJ2 in ischemic brain using a highly specific antibody-independent method. Whole hemisphere concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 (∼24 nM) detected in these experiments are significantly less than the concentrations required to produce toxicity in primary neuronal culture; however, whole hemisphere concentrations may not reflect intraneuronal concentrations in the penumbral region where COX-2 expression is selectively induced within neurons after ischemia. Additionally, 15d-PGJ2 is highly reactive, and may readily bind to sulfhydryl-containing proteins. Thus, total hemispheric free 15d-PGJ2 concentration may be much less than its concentration within the ischemic neuron in the penumbra.

The increase in [15d-PGJ2] after ischemia may be due to increased expression of COX-2 resulting in increased production of PGD2, or the increased conversion of PGD2 to CyPGs after hypoxia/ischemia, or both. To explore these mechanisms, primary neurons were incubated with biotinylated arachidonic acid or PGD2 and subjected to hypoxia. Binding of biotinylated arachidonic acid metabolites to endogenous proteins significantly increased after hypoxia, concomitant with increased COX-2 activity. Incubation with biotinylated PGD2 also produced similar changes. These results indicate that the increased generation of CyPGs in neurons after hypoxia may be the result of both increased COX-2 activity and an increased rate of dehydration of PGD2 to CyPGs. Arachidonic acid, PGD2 and PGE2 don't modify proteins directly; thus, the biotinylated proteins detected here most likely represent modification from CyPGs.

CyPGs have been shown to have both protective and injurious effects in neural systems. A number of studies have shown that 15d-PGJ2 and other CyPGs such as PGJ2 and Δ12-PGJ2 can induce apoptosis in a range of cell systems, including neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells, mouse oligodendrocytes, rat mesencephalic primary cells and primary cortical neurons (Kim et al 1993; Kondo et al 2002a; Li et al 2004a; Rohn et al 2001; Saito et al 2003). Selective dopaminergic neuron loss in the substantia nigra and the formation of Ub-protein aggregates in spared neurons in PGJ2 microinjected mice has been reported, further confirming the potential neurotoxic effects of CyPGs in vivo (Pierre et al 2009). Other studies suggest that 15d-PGJ2 may be neuroprotective in some ischemia models via anti-inflammatory effects mediated by PPARγ receptor activation (Lin et al 2006; Pereira et al 2006; Zhao et al 2006). To determine whether increased 15d-PGJ2 is either protective or injurious to neuronal cells in vitro, primary neurons were incubated with 15d-PGJ2 at varying concentrations under normoxic and hypoxic conditions. 15d-PGJ2 significantly increased neuronal cell death accompanied with the accumulation of Ub-proteins in surviving cells. Significant neuroprotection was not observed at any dose. Furthermore, the present study demonstrates that the neurotoxic effect of 15d-PGJ2 is mediated through a PPARγ independent mechanism, since incubation with CAY10410, a structural analogue of 15d-PGJ2 and a PPARγ agonist lacking an electrophilic carbon, failed to induce 15d-PGJ2 - like effects. Similarly, another 15d-PGJ2 analog, 15d-PGD2 which lacks the cyclopentenone ring structure and PPARγ agonist activity, also failed to show neurotoxic effects in the same dose range. Altogether, these results indicate that the electrophilic nature of 15d-PGJ2, which enables covalent modification of many proteins, is responsible for its neurotoxic effects.

An important intracellular target of CyPGs might be UCH-L1, one of the deubiquitinating enzymes selectively and highly expressed in brain. It has been reported that Δ12-PGJ2, another CyPG, inhibits UCH-L1 activity in vitro and disrupts the UPP, resulting in accumulation of Ub-proteins and cell death in neuroblastoma cells and primary mesencephalic neurons (Li et al 2004b). In the present study, covalent modification and inhibition of UCH-L1 by 15d-PGJ2 has been confirmed using recombinant protein and in intact neurons through various approaches. Aberrant modification and malfunction of UCH-L1 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative diseases including PD and AD (Choi et al 2004; Liu et al 2009). However, its role in ischemic neuronal injury is still largely unknown and controversial. In the current study, two complementary approaches were applied to test the role of UCH-L1 function in ischemic neuronal death. First, primary neurons were incubated with the specific UCH inhibitor LDN, to inhibit endogenous UCH-L1 activity. Second, exogenous UCH-L1 was delivered into neurons by cell-permeable TAT-UCH-L1 fusion proteins. The protective effect of TAT-UCH-L1 WT and the exacerbating effect of LDN on hypoxic neuronal injury suggest that UCH-L1 plays an important role in maintaining cell homeostasis and viability after hypoxia. This finding is consistent with recent findings that UCH-L1 function is important for synaptic transmission and neuronal function (Gong et al 2006; Sakurai et al 2008) while down-regulation of UCH-L1 by antisense cDNA in mouse neuroblastoma cells increased the cell's sensitivity to oxygen-glucose deprivation treatment (Shan et al 2004). Koharudin et al found that covalent modification of UCH-L1 by CyPGs dramatically disrupts the structure of UCH-L1 as determined by NMR spectroscopy, resulting in unfolding and aggregation of the protein. This CyPG effect on UCH-L1 structure is dependent upon a single highly conserved cysteine residue in UCH-L1, suggesting that CyPG binding to UCH-L1 may have important functional effects on UCH-L1 function and be an important signaling mechanism (Koharudin et al 2010). Thus the results from the current study and others suggest that modification and inhibition of UCH-L1 by CyPGs may have important effects on UCH-L1 function and increase the susceptibility of neurons to hypoxic and other pathogenic stresses.

15d-PGJ2 has been reported to adduct a number of other important cellular proteins including glutathione-S-transferase P1, thioredoxin, heat-shock protein 90 and some cytoskeletal proteins such as actin, tubulin and vimentin (Aldini et al 2007; Ogburn and Figueiredo-Pereira 2006; Sanchez-Gomez et al 2007; Shibata et al 2003a), and our results indicate that CyPGs may have increased binding to many other proteins after hypoxia. However, it is noteworthy that not every protein containing cysteine residues can be modified by 15d-PGJ2, and not every modification will cause inactivation of the target protein as occurs with UCH-L1 (Koharudin et al 2010; Renedo et al 2007). Furthermore, 15d-PGJ2-induced neurotoxicity could involve mechanisms in addition to UCH-L1 modification. For instance, another CyPG, PGJ2, was reported to affect UPP function by alteration of expression and function of proteasome components and sequestosome (Wang and Figueiredo-Pereira 2005; Wang et al 2006)

In summary, our results show that inhibition of UCH-L1 activity exacerbates hypoxic neuronal injury in primary neuronal culture. We found that endogenous [15d-PGJ2] is increased in ischemic brain and that 15d-PGJ2 binds to UCH-L1 and inhibits its activity in vitro. Inhibition of endogenous UCH-L1 by LDN exacerbates hypoxic cell death and results in accumulation of Ub-proteins in hypoxic neurons. 15d-PGJ2 treatment induces apoptosis and accumulation of Ub-proteins in primary neurons. These results suggest that CyPGs produced during hypoxia or ischemia can inhibit UCH-L1 activity and exacerbate neuronal injury by disruption of the UPP resulting in accumulation of Ub-proteins. Malfunction of UCH-L1, interruption of the UPP and accumulation of Ub-proteins in brain has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders including Parkinson's disease. Thus, agents that compete for the CyPG binding site on UCH-L1 could have utility in the treatment of stroke and neurodegenerative diseases. To further evaluate this hypothesis, additional studies involving pharmacological inhibition of UCH-L1 in stroke models are necessary to confirm that UCH-L1 activity plays an important role in determining cell death and outcome in vivo. Additional studies are required to confirm that CyPGs bind to UCH-L1 in vivo.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH NINDS R0137549 and the VA Merit Review program (SHG). The authors thank Pat Strickler for secretarial support, Drs. Jun Chen and Guodong Cao (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh) for providing the TAT-containing plasmid and Dr. Billy W. Day (University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh) for helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest. Contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahmad M, Zhang Y, Liu H, Rose ME, Graham SH. Prolonged opportunity for neuroprotection in experimental stroke with selective blockade of cyclooxygenase-2 activity. Brain Res. 2009;1279:168–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldini G, Carini M, Vistoli G, Shibata T, Kusano Y, Gamberoni L, Dalle-Donne I, Milzani A, Uchida K. Identification of actin as a 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 target in neuroblastoma cells: mass spectrometric, computational, and functional approaches to investigate the effect on cytoskeletal derangement. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2707–18. doi: 10.1021/bi0618565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G, Pei W, Ge H, Liang Q, Luo Y, Sharp FR, Lu A, Ran R, Graham SH, Chen J. In Vivo Delivery of a Bcl-xL Fusion Protein Containing the TAT Protein Transduction Domain Protects against Ischemic Brain Injury and Neuronal Apoptosis. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5423–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05423.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Levey AI, Weintraub ST, Rees HD, Gearing M, Chin LS, Li L. Oxidative modifications and down-regulation of ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase L1 associated with idiopathic Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:13256–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314124200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colgan L, Liu H, Huang SY, Liu YJ. Dileucine motif is sufficient for internalization and synaptic vesicle targeting of vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Traffic. 2007;8:512–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Bueno B, Madrigal JL, Lizasoain I, Moro MA, Lorenzo P, Leza JC. The anti-inflammatory prostaglandin 15d-PGJ2 decreases oxidative/nitrosative mediators in brain after acute stress in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;180:513–22. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge P, Luo Y, Liu CL, Hu B. Protein aggregation and proteasome dysfunction after brain ischemia. Stroke. 2007;38:3230–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.487108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giasson BI, Lee VM. Are ubiquitination pathways central to Parkinson's disease? Cell. 2003;114:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B, Cao Z, Zheng P, Vitolo OV, Liu S, Staniszewski A, Moolman D, Zhang H, Shelanski M, Arancio O. Ubiquitin hydrolase Uch-L1 rescues beta-amyloid-induced decreases in synaptic function and contextual memory. Cell. 2006;126:775–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi T, Snipes JA, Kis B, Shimizu K, Busija DW. Cyclooxygenase-2 mediates the development of cortical spreading depression-induced tolerance to transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140:723–30. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabuta T, Setsuie R, Mitsui T, Kinugawa A, Sakurai M, Aoki S, Uchida K, Wada K. Aberrant molecular properties shared by familial Parkinson's disease-associated mutant UCH-L1 and carbonyl-modified UCH-L1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1482–96. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IK, Lee JH, Sohn HW, Kim HS, Kim SH. Prostaglandin A2 and delta 12-prostaglandin J2 induce apoptosis in L1210 cells. FEBS Lett. 1993;321:209–14. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80110-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer SA, Lenhard JM, Willson TM, Patel I, Morris DC, Lehmann JM. A prostaglandin J2 metabolite binds peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and promotes adipocyte differentiation. Cell. 1995;83:813–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koharudin LM, Liu H, Di Maio R, Kodali RB, Graham SH, Gronenborn AM. Cyclopentenone prostaglandin-induced unfolding and aggregation of the Parkinson disease-associated UCH-L1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6835–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002295107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Shibata T, Kumagai T, Osawa T, Shibata N, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Iwata M, Noguchi N, Uchida K. 15-Deoxy-Delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2: The endogenous electrophile that induces neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002a;21:21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112212599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo M, Shibata T, Kumagai T, Osawa T, Shibata N, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S, Iwata M, Noguchi N, Uchida K. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2): the endogenous electrophile that induces neuronal apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002b;99:7367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112212599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Wu S, Hickey RW, Rose ME, Chen J, Graham SH. Neuronal cyclooxygenase-2 activity and prostaglandins PGE2, PGD2, and PGF2 alpha exacerbate hypoxic neuronal injury in neuron-enriched primary culture. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:490–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Wu S, Ahmad M, Jiang J, Liu H, Nagayama T, Rose ME, Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Borisenko GG, Belikova N, Chen J, Kagan VE, Graham SH. The cyclooxygenase site, but not the peroxidase site of cyclooxygenase-2 is required for neurotoxicity in hypoxic and ischemic injury. J Neurochem. 2010;113:965–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Jansen M, Ogburn K, Salvatierra L, Hunter L, Mathew S, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Neurotoxic prostaglandin J2 enhances cyclooxygenase-2 expression in neuronal cells through the p38MAPK pathway: a death wish? J Neurosci Res. 2004a;78:824–36. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Melandri F, Berdo I, Jansen M, Hunter L, Wright S, Valbrun D, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Delta12-Prostaglandin J2 inhibits the ubiquitin hydrolase UCH-L1 and elicits ubiquitin-protein aggregation without proteasome inhibition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004b;319:1171–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TN, Cheung WM, Wu JS, Chen JJ, Lin H, Chen JJ, Liou JY, Shyue SK, Wu KK. 15d-prostaglandin J2 protects brain from ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:481–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000201933.53964.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CL, Ge P, Zhang F, Hu BR. Co-translational protein aggregation after transient cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Liu ZQ, Chen CX, Magill S, Jiang Y, Liu YJ. Inhibitory regulation of EGF receptor degradation by sorting nexin 5. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:537–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Fallon L, Lashuel HA, Liu Z, Lansbury PT., Jr The UCH-L1 gene encodes two opposing enzymatic activities that affect alpha-synuclein degradation and Parkinson's disease susceptibility. Cell. 2002;111:209–18. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lashuel HA, Choi S, Xing X, Case A, Ni J, Yeh LA, Cuny GD, Stein RL, Lansbury PT., Jr Discovery of inhibitors that elucidate the role of UCH-L1 activity in the H1299 lung cancer cell line. Chem Biol. 2003;10:837–46. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Meray RK, Grammatopoulos TN, Fredenburg RA, Cookson MR, Liu Y, Logan T, Lansbury PT., Jr Membrane-associated farnesylated UCH-L1 promotes alpha-synuclein neurotoxicity and is a therapeutic target for Parkinson's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4635–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806474106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller R. The role of the ubiquitin proteasome system in ischemia and ischemic tolerance. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:243–60. doi: 10.1177/1073858408327809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meray RK, Lansbury PT., Jr Reversible monoubiquitination regulates the Parkinson disease-associated ubiquitin hydrolase UCH-L1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10567–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611153200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TM, Donnelly MK, Crago EA, Roman DM, Sherwood PR, Horowitz MB, Poloyac SM. Rapid, simultaneous quantitation of mono and dioxygenated metabolites of arachidonic acid in human CSF and rat brain. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:3991–4000. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne GL, Musiek ES, Morrow JD. The cyclopentenone (A2/J2) isoprostanes--unique, highly reactive products of arachidonate peroxidation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:210–20. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musiek ES, Breeding RS, Milne GL, Zanoni G, Morrow JD, McLaughlin B. Cyclopentenone isoprostanes are novel bioactive products of lipid oxidation which enhance neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1301–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M, Uchimura K, Zhu RL, Nagayama T, Rose ME, Stetler RA, Isakson PC, Chen J, Graham SH. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition prevents delayed death of CA1 hippocampal neurons following global ischemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:10954–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddo S. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in Alzheimer's disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:363–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00276.x. 2008/02/13 ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogburn KD, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Cytoskeleton/endoplasmic reticulum collapse induced by prostaglandin J2 parallels centrosomal deposition of ubiquitinated protein aggregates. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:23274–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600635200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira MP, Hurtado O, Cardenas A, Bosca L, Castillo J, Davalos A, Vivancos J, Serena J, Lorenzo P, Lizasoain I, Moro MA. Rosiglitazone and 15-deoxy-Delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2 cause potent neuroprotection after experimental stroke through noncompletely overlapping mechanisms. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:218–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre SR, Lemmens MA, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Subchronic infusion of the product of inflammation prostaglandin J2 models sporadic Parkinson's disease in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:18. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portera-Cailliau C, Price DL, Martin LJ. Non-NMDA and NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxic neuronal deaths in adult brain are morphologically distinct: further evidence for an apoptosis-necrosis continuum. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378:88–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renedo M, Gayarre J, Garcia-Dominguez CA, Perez-Rodriguez A, Prieto A, Canada FJ, Rojas JM, Perez-Sala D. Modification and activation of Ras proteins by electrophilic prostanoids with different structure are site-selective. Biochemistry. 2007;46:6607–16. doi: 10.1021/bi602389p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohn TT, Wong SM, Cotman CW, Cribbs DH. 15-deoxy-delta12, 14-prostaglandin J2, a specific ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, induces neuronal apoptosis. Neuroreport. 2001;12:839–43. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103260-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Takahashi S, Takagaki N, Hirose T, Sakai T. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12, 14)-prostaglandin J2 induces apoptosis through activation of the CHOP gene in HeLa cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;311:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M, Sekiguchi M, Zushida K, Yamada K, Nagamine S, Kabuta T, Wada K. Reduction in memory in passive avoidance learning, exploratory behaviour and synaptic plasticity in mice with a spontaneous deletion in the ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 gene. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27:691–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gomez FJ, Gayarre J, Avellano MI, Perez-Sala D. Direct evidence for the covalent modification of glutathione-S-transferase P1-1 by electrophilic prostaglandins: implications for enzyme inactivation and cell survival. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;457:150–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh T, Lipton SA. Redox regulation of neuronal survival mediated by electrophilic compounds. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setsuie R, Wada K. The functions of UCH-L1 and its relation to neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem Int. 2007;51:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan ZZ, Masuko-Hongo K, Dai SM, Nakamura H, Kato T, Nishioka K. A potential role of 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2 for induction of human articular chondrocyte apoptosis in arthritis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37939–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402424200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Kondo M, Osawa T, Shibata N, Kobayashi M, Uchida K. 15-deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2. A prostaglandin D2 metabolite generated during inflammatory processes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10459–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Yamada T, Ishii T, Kumazawa S, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J, Uchida K. Thioredoxin as a molecular target of cyclopentenone prostaglandins. J Biol Chem. 2003a;278:26046–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata T, Yamada T, Kondo M, Tanahashi N, Tanaka K, Nakamura H, Masutani H, Yodoi J, Uchida K. An endogenous electrophile that modulates the regulatory mechanism of protein turnover: inhibitory effects of 15-deoxy-Delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 on proteasome. Biochemistry. 2003b;42:13960–8. doi: 10.1021/bi035215a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraki T, Kamiya N, Shiki S, Kodama TS, Kakizuka A, Jingami H. Alpha,beta-unsaturated ketone is a core moiety of natural ligands for covalent binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:14145–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500901200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis K, Sanchez-Gomez FJ, Perez-Sala D. Identification of novel protein targets for modification by 15-deoxy-Delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2 in mesangial cells reveals multiple interactions with the cytoskeleton. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:89–98. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida K, Shibata T. 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2: an electrophilic trigger of cellular responses. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:138–44. doi: 10.1021/tx700177j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernace VA, Schmidt-Glenewinkel T, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Aging and regulated protein degradation: who has the UPPer hand? Aging cell. 2007;6:599–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Inhibition of sequestosome 1/p62 up-regulation prevents aggregation of ubiquitinated proteins induced by prostaglandin J2 without reducing its neurotoxicity. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Aris VM, Ogburn KD, Soteropoulos P, Figueiredo-Pereira ME. Prostaglandin J2 alters pro-survival and pro-death gene expression patterns and 26 S proteasome assembly in human neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21377–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Zhang Y, Strong R, Grotta JC, Aronowski J. 15d-Prostaglandin J2 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, promotes expression of catalase, and reduces inflammation, behavioral dysfunction, and neuronal loss after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:811–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]