Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) are the major site of action for endogenous hormones and neurotransmitters. Early drug discovery efforts focused on determining whether ligands could engage G protein coupling and subsequently activate or inhibit cognate “second messengers.” Gone are those simple days as we now realize that receptors can also couple βarrestins. As we delve into the complexity of ligand-directed signaling and receptosome scaffolds, we are faced with what may seem like endless possibilities triggered by receptor-ligand mediated events.

Introduction

GPCRs are ideal targets for pharmaceutical development with the goal of either mimicking the normal transmitter response or tempering it. In recent years, targeting GPCRs has become more complicated as we realize that drug action at receptors is “context dependent” such that activation and inhibition is limited to the response evaluated and “agonist” and “antagonist” become terms that reflect a particular condition of the experimental or physiological output [1-3]. Further, we have realized that GPCRs couple to other proteins besides G proteins. Of these, the βarrestins have proven to be critical regulators of GPCR signaling. Therefore, rather than limiting the concept of receptor activation to its coupling to a particular G protein, GPCR signaling may be envisioned as an event caused by a ligand-mediated conformational shift in receptor structure that leads to rearrangement of a signaling scaffold to recruit or dispel certain signaling players. In this sense βarrestins play a pivotal role in determining what players are recruited or dispelled, and thus, acting as facilitators, stabilizers or dampening agents, function in directing GPCR signaling.

In recent years, signaling via βarrestins has been demonstrated in cell culture models for many GPCRs [see 4 for review] and there appears to be some bias whereby certain ligands will preferentially engage βarrestins to activate particular cascades [5-7]. An interesting example of this is carvedilol, which has been known as a “beta-blocker” but has now been shown to activate ERK pathways via βarrestin-dependent signaling mechanisms suggesting that it is an “activator” at the β2 adrenergic receptor in respect to this pathway [6]). As the implications of the βarrestin-directed signaling pathways begin to emerge in cellular and in animal studies [8], screening for both βarrestin interaction and second messenger activation may prove to be an important early step in drug discovery efforts.

I. High Content Screening Technology

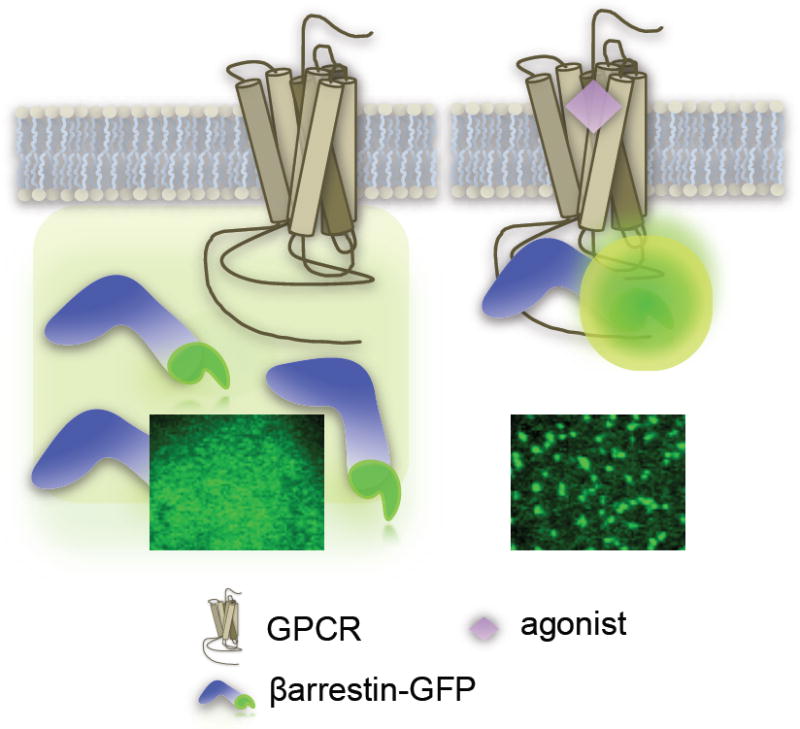

The monitoring of βarrestin recruitment to activated receptors has become a popular mode of measuring GPCR activity and is described as a ‘universal’ GPCR platform owing to the fact that it is G-protein independent, such that GPCRs will recruit βarrestins regardless of the nature of the G protein to which they couple [9]. One of the earliest methods for detecting GPCR-βarrestin interactions evaluated the “translocation” or redistribution of a green-fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged βarrestin from the cytosol which leads to the accumulation of intensely green punctae on the membrane or in vesicles (Figure 1) [10-12]. Oakley et al., used this approach to define two classes of GPCRs- those that recruit βarrestin to the plasma membrane yet dissociate from the βarrestin upon internalization (Class A) and those that recruit βarrestin to the plasma membrane and retain the βarrestin upon internalization into clathrin coated vesicles (Class B) [13]. This redistribution can be visualized and quantified on the high content scale using automated fluorescence-based microscopic imaging coupled to automated image-analysis software.

Figure 1.

Imaging Translocation

A. Transfluor™ by Molecular Devices

A high content screening platform based on this approach, named Transfluor™, originally developed by Norak, Inc., is now offered by Molecular Devices (www.moleculardevices.com). The optimal cell type used in this assay grows in a monolayer, has good adherence properties and has a large cytosol to nucleus ratio to optimize visibility. A benefit of this microtiter plate-based, fluorescence bioassay is that it measures the translocation of βarrestin-GFP such that GFP acts as the probe so it is not necessary to use a fluorescent dye or secondary substrate [9]. A somewhat limiting drawback is that it requires an expensive, dedicated image analysis system; data storage and analysis, due to large imaging files, can also represent a significant challenge. However it does provide more information content than single parameter assays such as those discussed later. Most notably, the imaging assay allows for visualization of the cells, which permits for parallel detection of putative compound liabilities such as cytotoxicity. An additional benefit of this assay is that visualizing the localization of the βarrestin (whether to the membrane or to the vesicles) will provide additional information regarding the drug effect with respect to ligand-induced trafficking.

II. High Throughput Screening Technologies

More recently, other βarrestin recruitment assay methods, that do not require expensive imaging instruments and have the advantage that they can be read with conventional multimode readers, have been developed. These include, 1) Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) [14,15] a protease-activated transcriptional reporter gene (TANGO™,Invitrogen (www.invitrogen.com, [14,16,17]) Enzyme Fragment Complementation (EFC) (Pathfinder™, DiscoveRx, www.discoverx.com [18]). Each can be used to assess agonist activation of the receptor, and, in conditions where basal βarrestin-receptor interactions are high, the assays can be configured for the identification of “inverse agonists.”

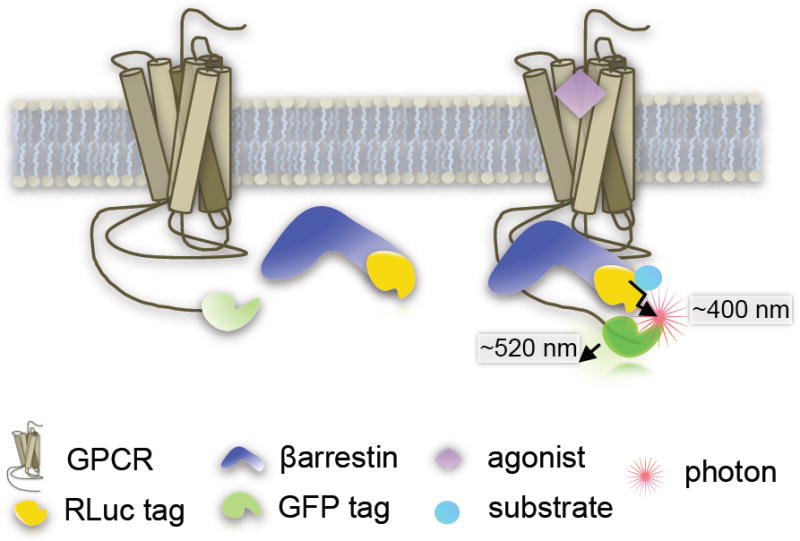

A. BRET

The bioluminescent energy transfer (BRET) assay was one of the earliest approaches utilized for assessing GPCR-βarrestin interactions and can be scaled for high throughput screening (HTS) applications [19-23]. BRET involves tagging the receptor of interest at the C-terminus with a fluorescent protein tag (such as enhanced green fluorescent protein-2, eGFP2 or GFP10, or yellow fluorescent protein, YFP) and the βarrestin with a Renilla luciferase (RLuc) tag (Figure 2). Alternatively, the tags can be interchanged, such that the fluorescent protein resides on the βarrestin and the RLuc tag resides on the receptor. It is best to empirically determine which protein should be tagged for each receptor: βarrestin interaction probed.

Figure 2.

BRET

Three generations of BRET exist namely: BRET1, BRET2 and (extended) eBRET [24,25] which can be distinguished by the Rluc substrate used (coelantrazine h, DeepBlueC™ or a protected form of coelantrazine h, termed EnduRen™, respectively) to produce a product and release a photon the emission of which can be measured. Upon βarrestin recruitment, the two tags come into close proximity and the light emitted from the RLuc reaction is sufficient to excite the GFP which will then emit a detectable signal at higher wavelength. The assay relies on a multimode plate reader to measure the light emitted in both spectra as the RLuc emission serves as an internal control and the GFP emission reflects the degree of excitation caused by the interaction. BRET is usually reported as a ratio of excitation of the two emissions (GFP/RLuc) which are determined by the BRET pairs and the substrate used.

There are substantial practical limitations from a HTS perspective such as high backgrounds, due to potential spectral overlap and rapid substrate catalysis resulting in very brief windows in which measurements are detectable following compound addition. To optimize the sampling time, substrate injection is usually required to enable signal detection. More recently, improvements in the BRET technology have been reported describing the use of novel luminophores, variants of RLuc, that may enhance the effectiveness of BRET for HTS applications [25]. Overall, BRET between βarrestin and the receptor is a proximal readout for receptor activation. The primary limitation however, is that BRET will occur whenever the two tags are in close proximity for energy transfer, even if a functional complex is not formed between receptor and βarrestin.

Currently, there are two prominent high throughput screening (HTS) platforms commercially available to study GPCR-βarrestin interactions: Invitrogen’s Tango™ GPCR Assay System [17,26] and the PathHunter™ system by DiscoveRx [27,28]. Both companies offer full assay development which involves the generation of stable cell lines expressing both modified GPCR and βarrestin proteins.

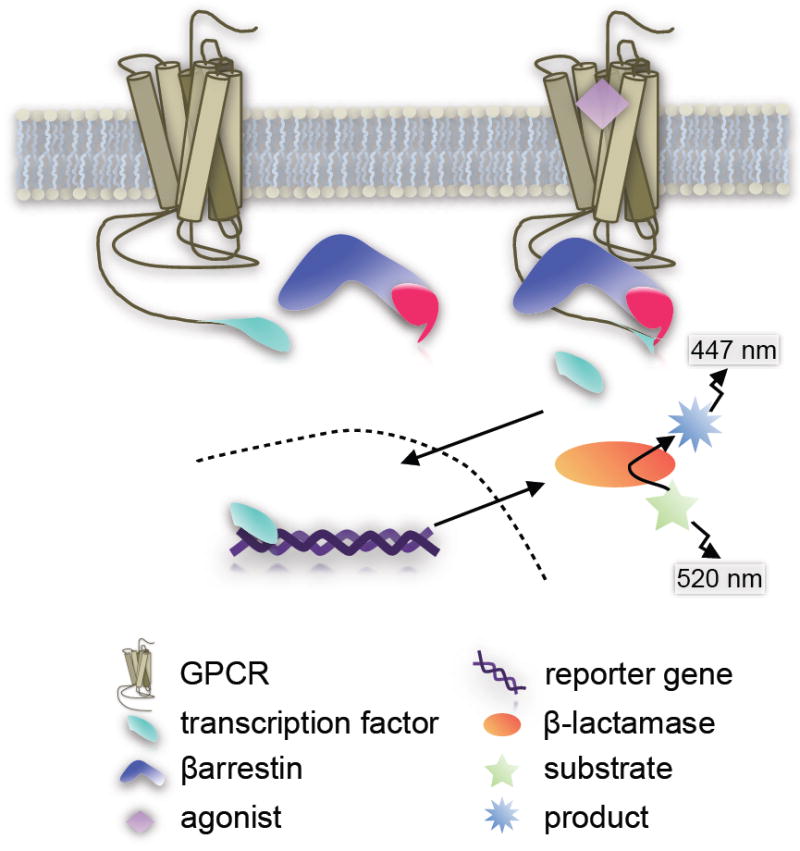

B. Invitrogen’s TANGO™ Assay System

The Tango™ GPCR Assay System utilizes a proprietary live-cell platform based upon transactivation of a reporter gene. Essentially, the C-terminus of the GPCR is tagged with a transcription factor (Gal4) via a protease cleavage site. The βarrestin is tethered with a TEV protease [29,30]. When the two proteins come together, the protease on the βarrestin cleaves the linker site on the GPCR thereby releasing the transcription factor which then translocates to the nucleus (Figure 3). The cells express a β-lactamase reporter gene which is subsequently activated by the transcription factor binding to a UAS promoter to produce the active enzyme. The production of β-lactamase is measured by its ability to catalyze a modified substrate tagged with two fluorophores. When the substrate is intact, the fluorophores undergo fluorescent resonance energy transfer (FRET) to generate ~520 nm emission (green cells). When the substrate is cleaved, FRET is abolished and the product fluoresces at 447 nm (blue cells) [17]. Detection of the signal can be measured by any fluorescent plate reader capable of generating 409 nm excitation and detecting ~520 nm emissions.

Figure 3.

Enzyme Fragment Complementation

According to the Invitrogen’s product sheet for individual cell lines, test compounds are added and then the cells are incubated for 5 (KOR, EDG6, others) to 16 (GPR119, CCR5, others) hours to allow for the βarrestin-receptor cleavage events. The cells are then treated with substrate for an additional 2 hours. The Tango™ assay is ratiometric, such that each receptor present in the cell during the testing period can only produce one βarrestin coupling event (the transcription factor can only be cleaved once per receptor). Therefore, the amount of β-lactamase activity measured is directly proportional to the number of βarrestin-receptor collisions. On the downside, the assay depends upon several cellular events to proceed between the agonist-binding event and the induction of the substrate-to-product disruption of FRET. Over the 5-16 hours of the assay, the protease activity, the transcription factor translocation to the reporter, the transcription factor binding to the reporter gene and initiating successful transcription followed by translation of a functional β-lactamase enzyme are all events that should not be impacted upon by test compound for the results to maintain their direct correlation to GPCR-βarrestin interaction. However, the robustness of the amplified signal output may be worth the sacrifice of the proximity of the receptor-βarrestin interactions. Further, the cleavage event should capture any ligand-induced receptor-βarrestin interaction independent of the duration or stability of that complex.

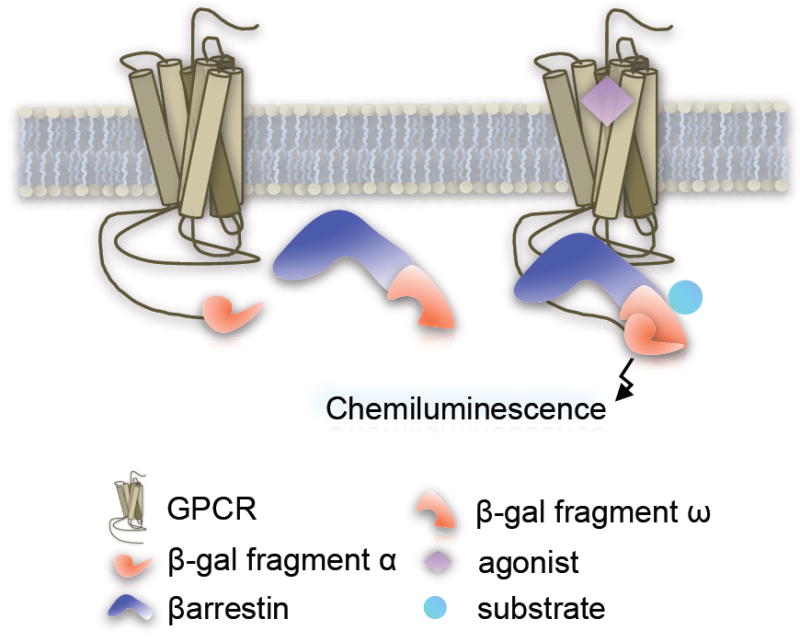

C. DiscoveRx Pathfinder™ Assay System

The DiscoveRx Pathfinder™ platform utilizes enzyme fragment complementation with β-galactosidase activity serving as an indicator of βarrestin-receptor interactions. In this assay, the GPCR is fused at the C-terminus to a mutant peptide fragment of the β-galactosidase (Prolink ™ or enzyme donor) and the βarrestin is tagged with the corresponding deletion mutant of β-galactosidase (enzyme acceptor) which is provided by DiscoveRx, engineered into host cells [31,32]. Agonist-induced βarrestin recruitment to the receptor brings the fragments in close enough proximity to reconstitute the functional enzyme (Figure 4). Output is measured as a chemiluminescent signal that is generated upon cleavage of exogenously added substrate by the reconstituted holoenzyme which can be detected using a standard multilabel plate reader.

Figure 4.

Reporter Gene Assay

DiscoveRx recommends that the enzyme substrate (provided as Galacton Star Substrate™) is added 90 minutes after the addition of the test compound and that the spectra is read ~60 minutes after addition of the substrate; the product is measured using standard luminescence absorbance spectra plate readers. The Pathfinder™ assay measures βarrestin-receptor interactions that are proximal to the receptor and do not require multiple downstream steps to produce the amplified signal. The downside of this platform is that measurements are taken at a limited time window at which only receptors and βarrestins that are actively engaged will be represented. Therefore, the assay only captures a snapshot of receptors bound to βarrestins during the period of substrate incubation.

Conclusions and Comparison of the HTS Assays

Both of the commercial assays offer the platforms for βarrestin2 specifically, although both companies will work with the researcher to develop custom cell lines, including those that assess the interaction with βarrestin1. While there is certainly much less in the research literature regarding βarrestin1-mediated regulation versus βarrestin2 mediated regulation of GPCRs, researchers should be cautioned that this does not necessarily indicate that βarrestin1 may be less important than βarrestin2 or that βarrestin1 and βarrestin2 are synonymous in their function and can therefore be interchanged in regard to significance. If one does choose to evaluate βarrestin1 interactions, which could potentially give novel information in regards to functional selectivity, a potential caveat is that βarrestin1 appears to have lower affinity than βarrestin2 for many receptors [33]. It is not clear from these studies whether the lower apparent affinity is due to low affinity of βarrestin1-GPCR interactions or if the endogenous βarrestin1 actually has much higher affinity (it is expressed at higher levels in most cells and tissues) and competes for the tagged βarrestin1 binding.

As the commercial platforms become more widely available, it becomes attractive to consider using them for studying particular receptors to elucidate the pharmacology of drug induced βarrestin interactions. However, it should be considered that these platforms are optimized for the detection of “hits” and that some sacrifice may be made in respect to normal function of the receptor. For example, the Pathfinder assay suggests a 90 minute incubation with agonist prior to substrate addition. Since most GPCRs have engaged in endocytic pathways, and since class A receptors (such as opioid receptors, adrenergic receptors, dopamine receptors, etc.) do not maintain the association with βarrestin2 during the internalization process, then one will only measure the βarrestin2-interaction within the receptor population that maintains the interaction at from the moment that the substrate is added. It is not clear what impact that time period, which can range upwards of 2 hours encompassing drug through substrate incubation periods, will have on receptor fate as most GPCRs are known to undergo internalization and down-regulation during that time frame. The internalization of the receptor may particularly impact on Class A GPCRs that do not maintain the βarrestin-receptor interaction upon internalization [13]. In this case, the only receptors that would be assessed are those that were not internalized and remain on the cell surface where they could still interact with the βarrestin. Therefore, the evaluation of the βarrestin2 interaction for a particular receptor may reflect only a small proportion of the receptors that are still activated, and may underestimate the degree of activation that was initially induced by the agonist. Furthermore, during that 90 minute period, a certain proportion of the receptors, that were activated may be downregulated by the time the measurement is made [34]. Ultimately, these regulatory events may not interfere with the detection of certain “hits” if receptor expression is in excess, but caution should be exercised when attempting to employ these approaches for basic molecular pharmacology characterization as sensitivity to temporal events is compromised.

There are several cell-based screening assays that are either commercially available or others that can be easily developed by individual laboratories without commercial restrictions, to assess GPCR-βarrestin interactions (Table 1). This approach is highly informative as it can be used to determine whether a compound activates the receptor to engage a βarrestin which may proceed independently of whatever downstream second messenger cascade is triggered. However, there may be compounds that do not recruit βarrestins that still engage G proteins, or other yet to be identified signaling cascades that will be missed if only this approach is taken. A prime example of this is the potent opioid analgesic, morphine, which under standard cellular conditions, fails to induce a robust recruitment of βarrestin to the MOR, and yet remains the gold-standard for pain management [35,36]. Finally, while an agonist may be found to engage GPCR-βarrestin interactions, it remains to be determined whether the interaction is relevant and whether it occurs in cellular environments wherein the receptor functions to control agonist-induced physiologies and behaviors.

Table 1.

Comparison Summary Table.

| Assay Technology | Transfluor | BRET | Tango | PathHunter |

| Assay Format | Imaging | Dual Channel Emission | Reporter Gene, FRET | Enzyme Fragment Complementation |

| Labels on GPCR/βarrestin | No Tag / GFP | Luciferase / GFP | Transcription factor/Protease | “Prolink” β-gal fragment/Complementary β-gal fragment |

| Equipment & Supplier | Fluorescent microscopy imaging Molecular Devices www.moleculardevices.com | Multimodal plate reader with injectors | Fluorescence plate reader Invitrogen www.Invitrogen.com | Conventional plate reader DiscoveRx www.DiscoveRx.com |

| Pros |

|

|

|

|

| Cons |

|

|

|

|

| References | (9,10) | (19-21) | (29,30) | (31,32) |

Acknowledgments

LMB is funded by NIH/NIDA grants DA025158; DA025259 and DA018860. PHM is funded by NIH/NINDS/NIDDK grants NS067631 and DK088125. LMB is a consultant to Trevena, Inc.

Abbreviations

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- RLuc

Renilla luciferase

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- EFC

enzyme fragment complementation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Laura M. Bohn, Departments of Molecular Therapeutics and Neuroscience, The Scripps Research Institute, 130 Scripps Way #2A2, Jupiter, FL 33458, lbohn@scripps.edu.

Patricia H. McDonald, Department of Molecular Therapeutics, The Scripps Research Institute, Translational Research Institute, 130 Scripps Way, #2A2, Jupiter FL 33458, mcdonaph@scripps.edu.

References

- 1.Urban JD, et al. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;320(1):1–13. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.104463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kenakin T. Collateral efficacy in drug discovery: taking advantage of the good (allosteric) nature of 7TM receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(8):407–415. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohn LM. Selectivity for G Protein or Arrestin-Meidated Signaling. In: Neve K, editor. Functional Selectivity of G Protein-Coupled Receptor Ligands: New Opportunities for Drug Discovery. Humana Press; 2009. pp. 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeWire SM, et al. Beta-arrestins and cell signaling. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:483–510. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmid CL, et al. Agonist-directed signaling of the serotonin 2A receptor depends on beta-arrestin-2 interactions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(3):1079–1084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708862105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wisler JW, et al. A unique mechanism of beta-blocker action: carvedilol stimulates beta-arrestin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(42):16657–16662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707936104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28(8):416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid CL, Bohn LM. Physiological and pharmacological implications of beta-arrestin regulation. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;121(3):285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakley RH, et al. The cellular distribution of fluorescently labeled arrestins provides a robust, sensitive, and universal assay for screening G protein-coupled receptors. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2002;1(1 Pt 1):21–30. doi: 10.1089/154065802761001275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barak LS, et al. A beta-arrestin/green fluorescent protein biosensor for detecting G protein-coupled receptor activation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(44):27497–27500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barak LS, et al. Real-time visualization of the cellular redistribution of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 and beta-arrestin 2 during homologous desensitization of the substance P receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(11):7565–7569. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, et al. Cellular trafficking of G protein-coupled receptor/beta-arrestin endocytic complexes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(16):10999–11006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oakley RH, et al. Differential affinities of visual arrestin, beta arrestin1, and beta arrestin2 for G protein-coupled receptors delineate two major classes of receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(22):17201–17210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910348199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charest PG, et al. Monitoring agonist-promoted conformational changes of beta-arrestin in living cells by intramolecular BRET. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(4):334–340. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heding A. Use of the BRET 7TM receptor/beta-arrestin assay in drug discovery and screening. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2004;4(3):403–411. doi: 10.1586/14737159.4.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doucette C, et al. Kappa opioid receptor screen with the Tango beta-arrestin recruitment technology and characterization of hits with second-messenger assays. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14(4):381–394. doi: 10.1177/1087057109333974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wetter JA, et al. Utilization of the Tango beta-arrestin recruitment technology for cell-based EDG receptor assay development and interrogation. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14(9):1134–1141. doi: 10.1177/1087057109343809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao X, et al. A homogeneous enzyme fragment complementation-based beta-arrestin translocation assay for high-throughput screening of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Biomol Screen. 2008;13(8):737–747. doi: 10.1177/1087057108321531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angers S, et al. Detection of beta 2-adrenergic receptor dimerization in living cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(7):3684–3689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060590697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertrand L, et al. The BRET2/arrestin assay in stable recombinant cells: a platform to screen for compounds that interact with G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRS) J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2002;22(1-4):533–541. doi: 10.1081/rrs-120014619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamdan FF, et al. High-throughput screening of G protein-coupled receptor antagonists using a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer 1-based beta-arrestin2 recruitment assay. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10(5):463–475. doi: 10.1177/1087057105275344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pfleger KD, Eidne KA. New technologies: bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) for the detection of real time interactions involving G-protein coupled receptors. Pituitary. 2003;6(3):141–151. doi: 10.1023/b:pitu.0000011175.41760.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boute N, et al. The use of resonance energy transfer in high-throughput screening: BRET versus FRET. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23(8):351–354. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfleger KD, et al. Extended bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (eBRET) for monitoring prolonged protein-protein interactions in live cells. Cell Signal. 2006;18(10):1664–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kocan M, et al. Demonstration of improvements to the bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) technology for the monitoring of G protein-coupled receptors in live cells. J Biomol Screen. 2008;13(9):888–898. doi: 10.1177/1087057108324032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanson BJ, et al. A homogeneous fluorescent live-cell assay for measuring 7-transmembrane receptor activity and agonist functional selectivity through beta-arrestin recruitment. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14(7):798–810. doi: 10.1177/1087057109335260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuinness D, et al. Characterizing cannabinoid CB2 receptor ligands using DiscoveRx PathHunter beta-arrestin assay. J Biomol Screen. 2009;14(1):49–58. doi: 10.1177/1087057108327329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Der Lee MM, et al. beta-Arrestin recruitment assay for the identification of agonists of the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor EDG1. J Biomol Screen. 2008;13(10):986–998. doi: 10.1177/1087057108326144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kunapuli P, et al. Development of an intact cell reporter gene beta-lactamase assay for G protein-coupled receptors for high-throughput screening. Anal Biochem. 2003;314(1):16–29. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnea G, et al. The genetic design of signaling cascades to record receptor activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(1):64–69. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710487105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yan YX, et al. Cell-based high-throughput screening assay system for monitoring G protein-coupled receptor activation using beta-galactosidase enzyme complementation technology. J Biomol Screen. 2002;7(5):451–459. doi: 10.1177/108705702237677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graham DL, et al. Application of beta-galactosidase enzyme complementation technology as a high throughput screening format for antagonists of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biomol Screen. 2001;6(6):401–411. doi: 10.1177/108705710100600606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohout TA, et al. beta-Arrestin 1 and 2 differentially regulate heptahelical receptor signaling and trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(4):1601–1606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041608198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig JA, Edwardson JM. Endocytosis and recycling of G protein-coupled receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1997;18(8):276–287. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J, et al. Role for G protein-coupled receptor kinase in agonist-specific regulation of mu-opioid receptor responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(12):7157–7162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groer CE, et al. An opioid agonist that does not induce μ-opioid receptor-β-arrestin interactions or receptor internalization. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71(2):549–557. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]