Abstract

Patient reported outcomes (PROs) play an essential role in clinical trials, though questions have been raised about the accuracy of PROs using long recall periods. This paper examines the utility of a PRO employing a single momentary assessment of pain in a sample of community rheumatology patients. We explore the accuracy and reliability of a single assessment versus the average of multiple assessments taken over 1-week, which is considered a common outcome reporting period. A secondary analysis of 128 patients who monitored their pain intensity with momentary data collections several times a day for a week and 3 months later for another week allowed a comparison of randomly-selected single momentary assessments with the average of many assessments from the week. Results from cross-sectional analyses of the first week were that levels of pain measured by single points were not significantly different than the week average in 4 of 5 analyses, but these single-point assessments had much higher variance. Correlations of single-point and week averages were below 0.70. Longitudinal analysis of change scores across 3 months also demonstrated considerable unreliability of single-point measures, thus the statistical power generated by single-point assessments was considerably less than the more reliable week average. Our conclusion is that single momentary assessments, at least for representing an outcome over a period of a week, are not ideal measures. We discuss alternative measurement strategies for efficiently collecting PRO data for a 1-week period using end-of-day diaries or 7-day recall measures.

Keywords: Pain, Measurement, Patient outcome assessment, Momentary assessment, Reliability of results

Patient reported outcomes (PROs) are an essential tool for evaluating many new medical interventions [1]; PROs allow researchers to capture patients' private experiences of illness, in particular, their symptoms and the impacts of those symptoms on their functioning [2]. PROs are self-reported and therefore are susceptible to various forms of distortion associated with self-reporting. One characteristic of PROs that is a source of potential bias is the length of recall specified in the instrument, known as the recall period [3]. The duration of the recall period is of concern, because there is considerable documentation that people have limited memory capacity, and recall over long periods may be influenced by various cognitive heuristics [4].

As an alternative to recall, momentary assessments inquire about immediate symptoms and states, thus avoiding recall bias. Examples include assessment of pain or fatigue intensity at the moment of the assessment. A premise of research addressing concerns with recall measurement is that reliable recall measures should show high correspondence with aggregated momentary assessment. Some argue that the observed correspondence of approximately 50% shared variance in some 7-day reporting periods is adequate [5], whereas others are less certain that it is adequate [6]. Further, there is little research examining the impact of recall periods of varying lengths for clinical outcome measures [7]. Based on this emerging research, the US Food and Drug Administration recently has taken a position that when PROs are used for evaluating the efficacy of new medications and devices, shorter recall periods should be used [8].

In this paper we examine if a single momentary assessment is adequate for characterizing a week, an alternative approach to using the average of multiple momentary assessments over 7 days to characterize weekly pain. We acknowledge that this approach may seem unusual since a moment is such a small slice of time and would likely provide an unreliable estimate, but argue that the results will be instructive from at least two perspectives. First, single momentary assessments are sometimes used as endpoints in clinical trials, for example, the Present Pain Index of the McGill Pain Inventory [9] or Visual Analog Scales for rating immediate pain [10] though this is not very common. Second, the idea of using single moments has been discussed by governmental regulators as a potential trial outcome. Although our initial reaction to this idea was negative, we realized there was no empirical support for our position (or for how poor an outcome this might be)–a situation this paper hopes to remedy.

Using data from an existing study of rheumatology patients in community care, we examine several psychometric characteristics of single momentary assessments of pain selected as might be done in a clinical trial (e.g., during a specific afternoon associated with a clinical visit). We compared the characteristics of a single, momentary assessment during the week the average of a large number of assessments over the week period. A 7-day reporting period was chosen, because it is a period that is often used in trials. We also examined the characteristics of change scores across a three-month interval using both measurement methods.

1. Methods

Momentary reports of pain were collected for two 1-week periods that were separated by 3 months. During each day of the 2 weeks, patients were prompted randomly several times a day to provide ratings. These ratings were averaged for each of the 2 weeks to provide the average momentary pain variable. At the end of each of the 2 weeks, patients completed a questionnaire that included recall questions about pain over the entire week.

1.1. Patients

Recruitment for this study was conducted from January 2004 to November 2004 at two community rheumatology offices. Two groups of patients were recruited by the study rheumatologist (ATK): those who were about to start a change in their treatment to improve control of their pain, and those not needing a change. The reason for identifying patients about to change their treatment was to ensure sufficient variability in change in pain for the longitudinal analyses. If we had only selected patients who were not modifying their treatment, then the only meaningful change in pain over the 3-month study period would be due to the natural course of the illness, and much of the observed variability in change might simply reflect random fluctuations.

Inclusion criteria included having a chronic pain disorder diagnosis (fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and/or osteoarthritis); having pain for more than 6 months; pain for ≥3 days per week; pain ≥3 h per day; and average level of pain >3 (on a 0–10 rating scale with 0 = no pain and 10 = excruciating pain). Other eligibility criteria were being between the ages of 18 and 80 years, having no sight or hearing problems, being fluent in English, having no difficulty holding a pen or writing, waking up by 10:00 am and going to bed no earlier than 7:00 pm, having no serious psychiatric impairment, no alcohol and/or drug problem, not planning any major surgery while participating in the study, and not having participated in an electronic diary study within the last 5 years.

Treatment regimen change was defined as starting a new treatment, adding a new treatment to the current regimen, switching to a different treatment, or increasing the current treatment dose. Those patients changing treatment had to be willing to postpone the new treatment for at least a week in order to collect momentary and recall data prior to the change. Patients were informed by their rheumatologist that their decision about whether or not to participate in the study would not affect the treatment they received, patients completed an informed consent with the research staff, and they were compensated $100 for completing the study. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Stony Brook University Institutional Review Board.

1.2. Materials and apparatus

Data collected for the study included demographic information, a recall pain questionnaire and momentary assessment ratings of pain utilizing an electronic diary. Patients completed a medical release form so that confirmation of their diagnosis could be obtained.

1.3. Paper questionnaires

The initial assessment included demographic information and other health measures not analyzed for this report. The Recall Questionnaire, administered at the conclusion of each one-week period of momentary monitoring, consisted of several visual analog scales assessing pain and mood “now” and over the last 7 days. The pain recall question was: “Place a mark on the following line to indicate the level of your USUAL PAIN over the last 7 days.” Directly under the question was a 100 mm horizontal line with the descriptor “None” at the left end and “Extreme” at the other end.

1.4. Electronic diary (ED)

The patient electronic diary (ED) was a Sony Clie computer (Model PEG610C) with proprietary software (invivodata, Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) specifically designed for the capture of momentary data. The ED was provided with a protective case with a belt strap to facilitate carrying the diary during a subject's daily routine. It measured approximately 11.5×7.5×1 cm and weighed 240 g (including the carrying case). Diary questions were presented on-screen for completion via a touch screen (5.8×5.8 mm) and entries were electronically stamped with the time and date. At the end of each week, patients returned to the laboratory and the data captured on the ED were transferred to a server where software stored the data and summarized compliance with the diary protocol.

The ED and support system included several features designed to enhance compliance. The ED issued an audible alarm used to prompt patients for diary entries and alerted them if they missed an assessment. The software also included provisions to help subjects incorporate the diary into their daily routine, such as allowing them to suspend prompting for defined periods of sleep, driving a car, or other uninterruptible activities. The system is described more fully elsewhere [11].

Pain was assessed using the following two questions: “Before Prompt: Were you in any pain?” and if yes, “How much pain did you feel?” (100-point visual analog scale with endpoints of “No pain” and “Extreme pain”). A rating of 0 was recorded when the patient indicated on the dichotomous question that they were in no pain. Seventeen additional questions about location, current activity, current affect, and a more detailed assessment of pain (sensory characteristics, affective responses, the degree to which activities were limited by pain, and a description of which activities were limited) were also included in each momentary assessment.

1.5. Procedure

At the initial visit, patients completed an informed consent, a medical release for confirmation of their diagnosis, and other questionnaires. Patients were trained in the use of the ED via a 60 minute presentation and practice session. They were also provided with a written manual to take home that served as a resource guide. The ED was programmed to deliver 9 prompts per day (across 16 waking hours) using a stratified random sampling scheme [12], specifically, generating a random prompt with uniform probability between 35 and 177 min after the previous prompt. Sampling in this manner yields an average prompt interval of 106 min or 9 times a day in a 16 hour day (assuming that the program was not suspended or that the patient did not nap). Once a set of ratings was completed, the program generated the time for the next prompt and so on.

The day after the training session, a follow-up phone call was conducted to ensure that patients were comfortable with the ED and to answer any questions. Three evening phone calls asking about pain behaviors were conducted during the week. After completing a week of momentary pain reports, patients returned to the research office with the ED and completed a Recall Pain Questionnaire. At this point, patients who were changing treatment were free to initiate the change. Approximately three months after the start of the first week of monitoring (mean= 86.1 days, SD=6.0; min=73; max=112), patients were contacted, came into the laboratory to receive the electronic diary, and completed the momentary ratings for a second week. At the end of the week, they again returned the ED and completed the 1-week recall report.

1.6. Analysis plan

We evaluated the possibility that a single momentary assessment could serve as a PRO for the measurement of pain in the context of a study with a one-week outcome period.

Several single momentary assessments were selected in various ways to fully explore the reliability of this assessment approach. They were compared with the average of all of the momentary ratings for the week; this mean is labeled “average week pain.” The first single-point assessments examined were chosen from three predetermined times (day of week and time of day), a procedure that might be used in a clinical trial where patients would be assessed at specific clinic visits: Monday morning between 8 am and 11 am, Wednesday afternoon between 3 pm and 6 pm, and Friday midday, between 11 am and 2 pm. Some patients did not have a momentary pain assessment in one or more of these timeframes, so the number of patients available varies across the three analyses. We also examined a single randomly-selected point from the week, based on the assumption that this selection process should avoid context and systematic bias, yet should have still have considerable variability. Finally, we examined the first momentary assessment point of the study as representative of a rating made without the history of many prior momentary ratings.

The first hypothesis is that there will be a difference in the level of pain estimated by time-and-date single points and average week pain. This would occur if the context associated with the single point, such as a clinic visit, was not representative of the week and that context impacted level of pain (e.g., as would be the case if there was a diurnal rhythm to pain). However, randomly-selected single points were not hypothesized to be different, because on average they should estimate the mean of all ratings for the week. Second, we hypothesized that the variability of the single points would be considerably greater than the variability of the average of all momentary reports for the week. Third, we hypothesize that single points should correlate with week average pain as well or better than 7-day recall ratings of average pain (r>0.75; see [6]) in order to be a viable outcome measure.

The next set of analyses move from cross-sectional to longitudinal using change in pain from the first to second wave of assessments using the randomly-selected point. We hypothesize that change scores based on a single point (follow-up point minus baseline point) will be less reliable than those based on week averages of all momentary points (follow-up week average minus baseline week average).

2. Results

Three hundred thirty-nine patients agreed to participate in a telephone screen, 294 were successfully contacted and completed the interview, and 220 were eligible. Of the 220 candidates who were eligible, 173 (79%) agreed to participate and 129 (59%) came to the research office to begin the protocol. Ultimately, 128 patients provided data during the first week of assessments, and 116 patients provided data at both weeks. Of these 116 patients, 87 entered the study with the intention to change their treatment at the end of the first week of data collection, and 29 patients were recruited who were not planning any change in their treatment.

Compliance with the momentary sampling protocol was based on the number of completed random prompts divided by the sum of the completed prompts plus prompts that were missed or prompts that would have been issued had the individual not utilized the suspend feature of the ED, which is a conservative approach to computing compliance. In Week 1 compliance was 86% (SD=9.4%, n=128) and in Week 2 compliance was 84% (SD=10.0%, n=116).

In Week 1, there were 128 patients available for analysis meeting a criterion of having at least 40 momentary measurements for the week (assuming that approximately 42 ED recording opportunities occur during a week, this would be a compliance level of 95%). Average momentary pain levels were computed for each patient as well as the within-person standard deviation. Over all patients, average momentary pain was 35.3.

3. Cross-sectional analyses of selected single momentary points

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were tested by comparing the characteristics of single momentary pain assessments with the characteristics of the average of all momentary pain assessments for Week 1. The first three rows of Table 1 show the results for these three single-point selections. Because the number of patients who had the selected point varied from selection to selection, we generated the average week pain for each selection. For example, 78 people had a Monday morning momentary assessment, and the average pain for that single assessment was 43.2. The average week pain for those 78 individuals was 38.4. Thus, if that Monday morning assessment was used to define outcome in a clinical trial, then a significantly higher level of pain would be reported for the group than would have been reported if the average week pain of momentary ratings for the entire week was used (t(77)=−2.22, p<0.05), and the variability of the single point would be considerably greater (29 versus 19; Variance Ratio Test, p<0.001). If Wednesday afternoon was used, then the estimate of pain intensity would not be biased (t(98)= 0.75 ns), although the variance would be considerably higher (28 versus 19; Variance Ratio Test, p<0.001). Finally, if Friday midday had been used, then the estimate would be higher than the average for the week by about 4 points, although not significantly so (t(112)=−1.50 ns); and again, the variability of the single point was considerably greater than of the average for the week (29 versus 19; Variance Ratio Test, p<0.001).

Table 1.

Cross-sectional comparisons of selected single points with average of all assessments for Week 1.

| Time period | N | Group average for single-point measures (SD) | Average of momentary points for week (SD) | Correlation of single point with momentary average |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monday morning | 78 | 43.2 (29.0) | 38.4 (18.5)* | 0.80 |

| Wednesday afternoon | 99 | 35.1 (27.7) | 36.8 (19.2) | 0.56 |

| Friday midday | 113 | 41.3 (27.7) | 38.6 (19.4) | 0.74 |

| Random | 128 | 38.5 (28.1) | 38.8 (19.7) | 0.64 |

| First of study | 128 | 39.3 (28.6) | 38.8 (19.7) | 0.68 |

p<0.05 difference between means.

The second approach to selecting a single point was to do it randomly. The mean of this random point was 38.5, which was not different than the average week pain of 38.8 (t(127)=0.1 ns), and the variability of the random point was 28.1, which is considerably higher than the 19.7 for the average week pain (Variance Ratio Test, p<0.001). Finally the third approach was to select the first momentary assessment of the study. The average of this single point of pain was 39.3 (28.6), and it was not significantly different than the average of all assessments for the entire week (t(127)=−0.3 ns).

The third hypothesis addressed the correlation between single points and the average week pain. The correlations ranged from 0.56 to 0.80 (see Table 1). The time-selected single points (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) yielded the greatest range of correlations. The correlation for first momentary assessment was 0.68 (r2=0.46, p<0.001), and the correlation for the randomly-selected point was 0.64 (r2=0.41, p=<0.001). Of course, like the other methods of selecting single points, estimates based on a single random point should be considered a sample of all random points. An intraclass correlation estimates the average association between all single points and mean for the week. Multilevel modeling [13] was used to compute the ICC (because the number of random points varies by patient), and it yielded a value of 0.67 (r2=0.45), which is similar to the single random point correlation with average week pain.

Thus, the first hypothesis that single points would be significantly different than the average of the full week of momentary ratings was supported for one of the five means of selecting single points. The second hypothesis that single points would have greater variability was supported. With the exception of the Monday morning point, correlations between the single points and the average week pain were not greater than 0.75, thus not providing support for hypothesis 3.

4. Longitudinal analyses of single momentary points

In clinical trials, single-point measurements could be used in the computation of change scores. Given the higher variability of the single points reported above, we expect that change scores based on two single points would be less reliable than change based on week means of momentary ratings. One hundred sixteen patients qualified for this analysis by having data at both weeks. We compared change scores based on a single, randomly-selected point with change scores based on the average week pain. We do not repeat the analyses of all of the other ways of selecting single points that were used in the previous section, because we thought the results would be quite similar given the high variability of all single points.

Change in average week pain from Week 1 to Week 2 was −8.2 with a standard deviation of 14.5, whereas change was −12.4 for change in the random, single moment with a standard deviation of 30.8. The single-point estimate of change was higher than change based on the week average, although marginally significant (t(115)=1.79, p<0.08). This demonstrates the potential for substantial inaccuracy in measurement of change in pain yielded by single random points: the estimate of change from the random points is approximately 50% higher than change based on change in average week pain. However, this difference is just a matter of sampling error: another sample of change in single points could have just as easily yielded a lower change score. The standard deviation was 14.5 for change in average week pain, which is about half the magnitude of the 30.8 SD for change in single-point pain. Finally, the correlation between change measured by average week pain and change measured by single random points was 0.59 (r2=0.35).

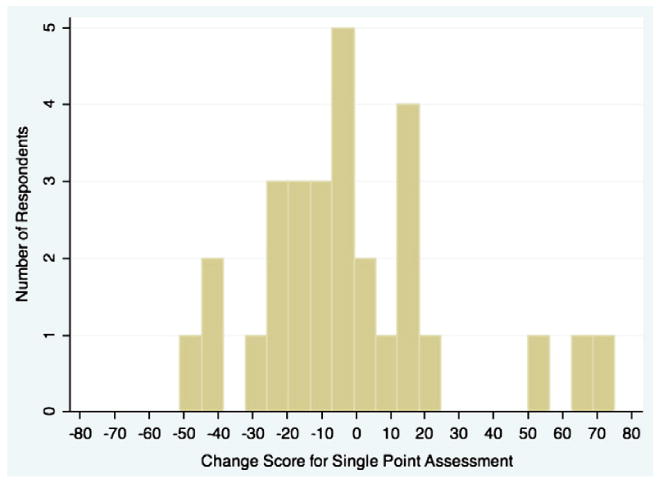

An additional way to explore these results is by characterizing patients by their change based on the average week pain scores and comparing the results with those based on single moments. Average week change scores are more reliable than the single-point change scores, because they are based on a large number of points (as shown above in the smaller standard deviation for the week scores versus any of the single points). The first comparison classifies individuals as having a considerable reduction in pain over time and we selected a criterion of a reduction of one standard deviation in the change score. For the average week variable, the standard deviation was 14.5 and 25% of the sample achieved a reduction in pain of at least this amount. Turning to the random moment variable, the one standard deviation criterion was 30.8 and 20% of the sample achieved this criterion. Although the percentages meeting the criterion are similar, the problem is that of the 26 individuals classified as having a large reduction in pain by the average week scores, only 58% of them were classified as having a large reduction by the single moment variable. This indicates a considerable degree of classification error. A second way of presenting the association is by selecting individuals who had little change in pain (we chose between −5 and +5) and examining their scores on the random change variable. Twenty-nine participants were identified as having this small amount of change and a histogram of their single moment change scores is shown in Fig. 1. It is clear that many individuals who had very little change as indicated by the average week measure would be said to have considerable change if the single-point measure had been used.

Fig. 1.

Histogram of change based on single-point scores for patients with little change based on week averages of momentary ratings (−5 to +5).

5. Discussion

This paper investigated the utility of using a single-point assessment as a potential outcome measure for characterizing a 1-week outcome period. A single momentary assessment could be a desirable measurement option due to low cost and burden. However, a single-point measure may not be a reasonable PRO candidate considering it only captures symptom experience in a small slice of time. The multiple momentary self-reports of pain examined in this paper have the distinct advantage of directly capturing subjective symptom states across the entire outcome reporting period (1 week) without the concern of bias associated with retrospection. Unless the phenomenon measured is very stable over time, then a single momentary assessment could be unreliable and could misrepresent the level of the outcome. This study investigated the utility of single-point assessments in several ways. It emulated clinical site visit single-point assessments based on momentary assessments that occurred in a selected window of time on a given day during the course of the study week. In some or most clinic trials, many time windows for clinic visits could be available, which would result in single-point data similar to that shown in the random point analyses. For comparison, we also chose a random point from the week of interest and the first point of the week.

Cross-sectional analyses suggested that a single momentary assessment is not likely to be optimal for clinical trials (or other research endeavors) for representing pain in a 1-week outcome period for three reasons. The first is that setting context or time of day may shift the single point away from the true week's average of pain. This was seen in the single point selected in Monday morning that was higher than the week average. In this case and patient population, it may be that pain is higher in the morning than most of the rest of the day. It is likely that other single-point PROs and other samples would show similar problems. Thus, when momentary assessments are taken at particular times-of-day or days-of-week and (unbeknownst to the investigator) that period has lower or higher levels of the PRO relative to the mean for the entire outcome period, the measure would not be accurate. In summary, mean levels of a PRO for an outcome period may not be well represented by single points.

Second, the variability of single momentary assessments was higher compared with variability of week averages: standard deviations for the single assessments were about 50% greater than SDs for the week averages. Since we are using week averages as a gold standard, this increased variability in single assessment outcomes may be viewed as error variance and this yields increased unreliability. For cross-sectional analyses, this means that the statistical power available to detect associations will be considerably lower when single-point momentary outcomes are used versus the power associated with week means.

Third, the correspondence between a single-point measure and the average of all moments for the week was quite varied and was generally not exceptionally strong. The variance shared by the time-selected assessments ranged from 31% to 64%. The level and range of these correlations is problematic as it demonstrates the unreliability of the single-point measure as a proxy for the average pain for the week. The variance shared for the random point and first point assessments ranged from 41% to 46%, thus also not providing an acceptable level of correspondence. As with level differences, both sampling error and systematic associations may be contributing to these associations. For example, it is possible that a particular time-of-day or day-of-week is typically more representative of a week's pain than other periods (for reasons we do not understand). In summary, the correspondence or agreement between single points and average pain for the week is modest at best.

The utility of single-point measurement was also investigated longitudinally as would be typical in clinical trials. We showed that there were many major errors of change scores based on single-point assessments relative to those based on week averages, indicating substantial unreliability. The degree of reliability of a measure has a direct influence on a study's statistical power and sample size. To explore the impact of differential reliability, we compared these parameters for change scores derived from the single-point measures and the week average measures. The number of patients needed to achieve a level of 0.90 power for the change over time of about 8 points using the average week pain of momentary ratings is 33. In contrast, by substituting the standard deviations from the random single-point measures, the number of patients required to achieve the same level of power is 149, approximately 4½ times as many subjects. This certainly would be a major practical issue for those conducting trials.

Our overall conclusion is that although single-point assessments theoretically have some positive features for serving as outcome measures in clinical trials, they are not attractive candidates for serving as outcomes representing a 1 week in duration outcome period. Single-point measures are relatively unreliable, which greatly decreases the statistical power afforded by a given trial design. Furthermore, there is the possibility that systematic influences of time-of-day and day-of-week could bias results, depending on the trial design and in particular the schedule for recording outcomes.

There are limitations to work presented in this paper. We have explored a 1-week outcome period, and this will not be the outcome period chosen for some studies. Our conclusions about single-point measures may not generalize to other outcome periods, although we strongly suspect that they will generalize to those longer than 1-week. Second, these results are limited by their focus on pain intensity and on this sample of chronically ill patients. Other outcomes may produce different results and those results may depend upon the particular patterning of the PRO over the outcome period. PROs with especially stable courses could produce more encouraging results for single-point outcomes. One example is physical functioning in a rheumatology population where one end-of-day (EOD) report corresponded quite well with the average of 14 days of EOD reports for interference due to pain (r's 0.84–0.89) and due to fatigue (r's 0.76–0.86) [7]. However, variables with greater fluctuations or with more systematic associations with certain times of the day or week may yield less reliable and more biased results than were shown here.

What course should researchers take if they wish to assess PROs for a 1-week period and desire to minimize recall bias? One strategy is to collect multiple momentary assessments with Experience Sample Methods or Ecological Momentary Assessments [14]. However, from a practical viewpoint, these data collection methods are generally expensive and carry considerable subject burden. Another common strategy is to use standardized assessment measures that utilize a 7-day recall period. Our research has indicated that such PROs for pain and fatigue can provide moderate correspondence but inflated symptom levels relative to the week average of momentary ratings [7]. We also recently explored an end-of-day (EOD) measurement strategy for pain and fatigue that we think has merit. The study in question examined rheumatology patients using both momentary and end-of-day reports across a month [15]. Without going into the study design details, we report the primary finding, which is shown in the Fig. 2. The analysis examined the correlation between the average pain for the week based on momentary reports and the average of 1 through 7 end-of-day reports for each of several pain measures. Note “pain intensity” which is shown by open circles. A single EOD pain intensity report correlated in the upper 70's with the week average of momentary reports. An average of 3 EOD reports resulted in an association of 0.92 and the average of 4 EOD reports yielded a correlation of 0.94. Thus, these multiple EOD reports are reasonable proxies of a full week of momentary ratings.

Fig. 2.

Correlation coefficients for several end-of-day pain measures that have been averaged over increasing numbers of days with the average of 7 days of 6/day momentary assessments. (Reprinted from Journal of Pain, 10, Broderick, J.E., Schneider, S., Schwartz, J.E., and Stone, A.A. Can end-of-day reports replace momentary assessment of pain and fatigue? Pages 274–281, Copyright (2009), with permission from Elsevier.)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA-85819; A.A.S., principal investigator). We thank Daniel Arnold and Steve Choi for their help in collecting the data. A.A.S. is a Senior Consultant for invivo-data, Inc. and a Senior Scientist with the Gallup Organization. The authors thank Drs. Alan Shields and Joseph Schwartz for their helpful suggestions.

Contributor Information

Arthur A. Stone, Email: Arthur.stone@sunysb.edu.

Joan E. Broderick, Email: joan.broderick@stonybrook.edu.

Alan T. Kaell, Email: atkaell@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Burke LB, Kennedy DL, Miskala PH, Papadopoulos EJ, Trentacosti AM. The use of patient-reported outcome measures in the evaluation of medicl products for regulatory approval. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:281–3. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PRO-MIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care May. 2007;45(5 Suppl 1):S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broderick JE, Stone AA, Calvanese P, Schwartz JE, Turk DC. Recalled pain ratings: a complex and poorly defined task. J Pain. 2006 Feb;7(2):142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorin AA, Stone AA. Recall biases and cognitive errors in retrospective self-reports: a call for momentary assessments. In: Baum A, Revenson T, Singer J, editors. Handbook of health psychology. Mahwah, N.J: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 405–14. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salovey P, Smith AF, Turk DC, Jobe JB, Willis GB. The accuracy of memory for pain: not so bad most of the time. Am Pain Soc J. 1993;2:181–91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stone AA, Broderick JB, Shiffman SS, Schwartz JE. Understanding recall of weekly pain from a momentary assessment perspective: absolute agreement, between- and within-person consistency, and judged change in weekly pain. Pain. 2004;107:61–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Broderick JE, Schwartz JE, Vikingstad G, Pribbernow M, Grossman S, Stone AA. The accuracy of pain and fatigue items across different reporting periods. Pain. 2008 Sep 30;139(1):146–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidance for Industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. 2009 doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-79. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30:191–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Litcher-Kelly L, Martino SA, Broderick JE, Stone AA. A systematic review of measures used to assess chronic musculoskeletal pain in clinical and randomized controlled clinical trials. J Pain. 2007 Dec;8(12):906–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiffman S, Hufford MR, Paty J. Subject experience diaries in clinical research. Part 1: the patient experience movement. Appl Clin Trials. 2001;10:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz JE, Stone AA. Strategies for analyzing ecological momentary assessment data. Health Psychol. 1998 Jan;17(1):6–16. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.17.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone AA, Broderick JE. Real-time data collection for pain: appraisal and current status. Pain Med. 2007 Oct;8(Suppl 3):S85–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broderick JE, Schwartz JE, Schneider S, Stone AA. Can end-of-day reports replace momentary assessment of pain and fatigue? J Pain. 2009;10:274–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]