Abstract

The establishment of cell type-specific dendritic arborization patterns is a key phase in the assembly of neuronal circuitry that facilitates the integration and processing of synaptic and sensory input. Although studies in Drosophila and vertebrate systems have identified a variety of factors that regulate dendrite branch formation, the molecular mechanisms that control this process remain poorly defined. Here, we introduce the use of the Caenorhabditis elegans PVD neurons, a pair of putative nociceptors that elaborate complex dendritic arbors, as a tractable model for conducting high-throughput RNAi screens aimed at identifying key regulators of dendritic branch formation. By carrying out two separate RNAi screens, a small-scale candidate-based screen and a large-scale screen of the ∼3000 genes on chromosome IV, we retrieved 11 genes that either promote or suppress the formation of PVD-associated dendrites. We present a detailed functional characterization of one of the genes, bicd-1, which encodes a microtubule-associated protein previously shown to modulate the transport of mRNAs and organelles in a variety of organisms. Specifically, we describe a novel role for bicd-1 in regulating dendrite branch formation and show that bicd-1 is likely to be expressed, and primarily required, in PVD neurons to control dendritic branching. We also present evidence that bicd-1 operates in a conserved pathway with dhc-1 and unc-116, components of the dynein minus-end-directed and kinesin-1 plus-end-directed microtubule-based motor complexes, respectively, and interacts genetically with the repulsive guidance receptor unc-5.

Keywords: PVD, Dendrite morphogenesis, Bicaudal D, Caenorhabditis elegans

INTRODUCTION

Dendrites receive and process synaptic and sensory inputs via elaborate dendritic networks or arbors. Although the complexity and shape of these networks vary widely among different neuronal subtypes, a given class of neuron displays highly stereotyped dendritic arbors (Grueber et al., 2005). Accordingly, cell type-specific dendritic arborization patterns help to define the specific inputs and functional outputs associated with a given neuronal subtype (Hausser et al., 2000). Dendritic branching represents a key step(s) in the formation of dendritic arbors. Whereas studies in Drosophila and vertebrate systems have identified a variety of molecules that regulate dendrite branching (Corty et al., 2009; Jan and Jan, 2010; Urbanska et al., 2008), the full repertoire of molecules controlling this crucial stage of dendrite development remains obscure.

RNA interference (RNAi) is a well-established powerful tool for identifying novel genes involved in a wide range of biological phenomena (Fire et al., 1998; Wolters and MacKeigan, 2008). In C. elegans, large-scale RNAi screens have been used to define key sets of genes involved in processes such as fat regulation (Ashrafi et al., 2003), longevity (Hamilton et al., 2005) and axon guidance (Schmitz et al., 2007). Therefore, we reasoned that RNAi screens in C. elegans might uncover novel regulators of dendritic branching. Specifically, we chose to carry out RNAi screens to identify genes that regulate the branching of PVD neuron dendrites in C. elegans. PVD neurons are bilaterally symmetric nociceptors that respond to harsh mechanical stimuli and cold temperatures (Chatzigeorgiou et al., 2010; Way and Chalfie, 1989). Importantly, these neurons elaborate large and complex dendritic arbors which envelop the body of late-larval and adult-staged animals (Oren-Suissa et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2010; Tsalik et al., 2003; Yassin et al., 2001), and provide an ideal system for studies aimed at identifying novel regulators of dendrite morphogenesis.

To date, mec-3, which encodes a LIM homeodomain transcription factor expressed in PVD neurons (Way and Chalfie, 1988; Way and Chalfie, 1989), as well as eff-1, which encodes a protein essential for cell fusion, are the only genes known to be required for the elaboration of PVD dendritic arbors (Oren-Suissa et al., 2010; Tsalik et al., 2003). By carrying out two RNAi screens, a small-scale candidate-based screen and a large-scale screen of chromosome IV, we identified 11 genes that either promote or suppress PVD dendrite branching. These include: bicd-1, homologs of which include Drosophila Bicaudal D (BicD) (Suter et al., 1989; Wharton and Struhl, 1989) and mammalian bicaudal D homolog 1 (BICD1) and bicaudal D homolog 2 (BICD2) (Baens and Marynen, 1997; Hoogenraad et al., 2001); dnc-1 and dli-1, which encode components of the cytoplasmic dynein minus-end-directed motor (Koushika et al., 2004); and unc-116, which encodes a component of the kinesin-1 plus-end-directed motor (Patel et al., 1993; Sakamoto et al., 2005). Drosophila BicD facilitates the localization and transport of mRNAs (Bullock and Ish-Horowicz, 2001; Bullock et al., 2006) and nuclei (Swan et al., 1999) via interactions with Dynein, and mammalian BICD1 and BICD2 co-precipitate with dynein and dynactin and function in dynein-mediated transport (Hoogenraad et al., 2001; Hoogenraad et al., 2003; Matanis et al., 2002). Given that a function for bicd-1 in dendritic branch formation had not been established, and the connections between bicd-1 and microtubule-based motors in other systems, we investigated the role of bicd-1 and the motor components retrieved from our screens in PVD dendrite branching.

Here, we demonstrate that loss of bicd-1 function results in the appearance of ectopic dendrite branches posterior and proximal to the PVD cell body with a concomitant reduction in the number of terminal branches elaborated distal to the PVD cell body. In addition, our bicd-1::YFP transcriptional reporter data, coupled with anatomical focus-of-action studies, indicate that bicd-1 is expressed, and primarily acts, in PVD neurons. Furthermore, we show that bicd-1 acts cooperatively with both dhc-1 and unc-116 to regulate PVD dendrite branching. Interestingly, our RNAi screens also identified unc-5, a known repulsive guidance receptor (Leung-Hagesteijn et al., 1992), as a regulator of PVD dendritogenesis and we present evidence that bicd-1 interacts genetically with unc-5 in this context. Together, these findings identify bicd-1 as a key regulator of dendrite branching in C. elegans and suggest novel mechanisms, crucial for proper dendrite morphogenesis, that may be conserved in higher-order organisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains

C. elegans strains were maintained on nematode growth media plates at 20°C (unless otherwise noted) using standard techniques (Brenner, 1974). The wild-type strain is N2 Bristol. The PVD transcriptional reporter is OH1422 [otIs138 (ser2prom3::GFP) X] (Tsalik et al., 2003) and the FLP transcriptional reporter is NY2030 [ynIs30 (Pflp4::GFP) I] (Kim and Li, 2004). All mutant strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. The temperature sensitive dhc-1(or195) mutants were maintained at 15°C and shifted to the restrictive temperature of 25°C for phenotypic analysis. bicd-1 is the gene name for C43G2.2 and is used throughout this study.

Strain construction

RZ117 [bicd-1(ok2731);otIs138], RZ119 [dhc-1(or195);otIs138], RZ120 [unc-116(e2310);otIs138], RZ121 [unc-5(e152);otIs138], RZ155 [unc-5(e53);otIs138], RZ134 [unc-6(ev400) otIs138], RZ131 [bicd-1(ok2731);ynIs30], RZ136 [dhc-1(or195);bicd-1(ok2731);otIs138], RZ103 [unc-116(e2310);bicd-1(ok2731);otIs138], RZ135 [unc-5(e152) bicd-1(ok2731);otIs138], RZ157 [unc-5(e53) bicd-1(ok2731);otIs138] and RZ165 [bicd-1(ok2731);unc-6(ev400) otIs138] were generated using standard techniques. bicd-1(ok2731) animals were backcrossed three times to N2 (wild type) prior to strain construction. Primers used to identify bicd-1(ok2731) IV mutant animals were (5′-3′): CATTAACATCTGTCTCTGTTCCAC, CATACATCTACGCTAGACTCC and GCAAGTGACCTCTTCAGTGAATTAC. Primers used to identify bicd-1(tm3421) IV mutant animals were (5′-3′): GAATGCTTGTTCAGAGGTTC, CACATCGCCAATCTTGACAC and TCAGGACGCAATGATTCAAG.

RNAi screening

RNAi by feeding was performed as previously described (Kamath and Ahringer, 2003; Schmitz et al., 2007) with minor modifications. Briefly, RNAi clones were grown for 16 hours in LB media with 50 μg/ml ampicillin. Bacterial cultures were seeded onto agar plates containing 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Sigma) and 50 μg/ml carbenicillin and allowed to dry for 24 to 48 hours at room temperature. Three L4 larval stage hermaphrodites were then placed on each plate, incubated for 4 days at 20°C and allowed to lay a brood. After incubation, young adult progeny were washed off feeding pates with M9 buffer and mounted on 5% agar pads. Approximately twenty adult progeny per RNAi clone were scored for the presence of defective PVD dendritic morphology, defined here as a qualitative increase or decrease in the number of secondary, tertiary or quaternary dendrites. All RNAi clones (kindly provided by Ji Y. Sze, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, NY, USA) assayed in the candidate-based screen were tested twice and subjected to at least two additional rounds of re-testing if ≥10% of animals displayed defective PVD morphology in either initial test. RNAi clones (Geneservice) (Fraser et al., 2000; Kamath et al., 2003) assayed in the large-scale screen were re-tested at least twice if ≥18% of animals displayed a defective PVD arborization pattern. Data from all RNAi tests (three to five tests per RNAi clone) were then pooled to generate an overall percentage of animals displaying defects. RNAi clones were considered positive if the overall percentage of animals displaying a defective PVD arborization pattern was ≥20% (Table 1). Note that RNAi against either dnc-1 or unc-32 produced very few animals that survived to adulthood. Therefore, it was not possible to assay the targeted twenty animals per test for these genes. Additionally, 335 (candidate screen: 7; chromosome IV screen: 328) of the 2830 total RNAi clones (candidate screen: 137; chromosome IV screen: 2693) were not assessed owing to technical difficulties (e.g. clone failed to grow, mold/bacterial contamination of seeded clone). All inserts from positive RNAi clones were sequenced to confirm their identities.

Table 1.

Candidate-based and large-scale RNAi screens identify genes required for the proper branching of PVD dendrites

Plasmid construction and transgenic strains

The bicd-1::YFP fusion construct was generated by PCR fusion (Hobert, 2002). Specifically, a 5977 bp fragment upstream of the ATG start codon of bicd-1 was amplified from N2 worm genomic DNA and fused to the yfp/unc-54 3′UTR cassette. bicd-1::YFP was injected into N2 wild-type animals at 25 ng/μl, using pRF4 rol-6(su1006) as an injection marker.

For cosmid rescue experiments, the C43G2 cosmid (2 ng/μl) was injected with mec-7::gfp and myo-3::rfp plasmids (50 ng/μl each). For cell type-specific rescue experiments, bicd-1 cDNA was PCR amplified from the C. elegans ORFeome clone OCE1182-7243564 (Open Biosystems) and cloned into pPD96.41, creating pZK01. After cloning the bicd-1 cDNA into pPD96.41, the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis System (Stratagene) was used to replace two nucleotides, C2646T and T3248C, which did not coincide with the predicted bicd-1 nucleotide sequence. The bicd-1 cDNA/unc-54 3′UTR cassette was then released from pZK01 and cloned into the pZK02 (ser2prom3 promoter) and pPD95.86 (myo-3 promoter) plasmids. Constructs were injected at 5ng/μl with pceh-22::gfp (pharyngeal GFP) and pBS SK Bluescript at 50 ng/μl each.

Quantification and photodocumentation of PVD dendrite branching defects

Unless otherwise noted, dendrite branching defects were scored at the young adult stage (52-58 hours post-hatch at 20°C or 42-44 hours post-hatch at 25°C). Dendrite branching defects were visualized with an Olympus IX 70 Microscope equipped with GFP and YFP optical filter sets (Chroma Technology). Images were captured with an Olympus Optronics digital camera and Magnafire 2.0 software.

Statistics

GraphPad Prism Software (Version 5.0b) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Development of the PVD neuron dendritic arbor

The otIs138 transcriptional reporter line (Tsalik et al., 2003) prominently labels the bilaterally symmetric PVD neurons and was used to characterize the development of PVD dendritic arbors from the L2 larval to the young adult stage. The primary anterior and posterior dendrites, which terminate posterior to the terminal bulb of the pharynx and at the endpoint of the tail, respectively, were clearly detectable by the L2 stage (Fig. 1A). Dorsally and ventrally directed secondary dendrites then grew out from the primary dendrites along the entire anteroposterior (A/P) axis of the animal (Fig. 1B). Upon reaching the hypodermal/muscle border, secondary dendrites executed an orthogonal turn, in either the anterior or posterior direction, and extended parallel to the primary dendrite (Fig. 1B). Next, tertiary dendrites sprouted from the orthogonal turnpoint of existing secondary dendrites and, subsequently, projected longitudinally away from secondary dendrites (Fig. 1C). At L3, quaternary dendrites grew out from the longitudinally projecting segments of secondary and tertiary dendrites, and projected towards either the ventral or dorsal midline (Fig. 1D). Outgrowth of the quaternary dendrites was complete by the L4 stage (Fig. 1E) and the resulting arborization pattern was maintained at the young adult stage (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Spatiotemporal pattern of PVD dendrite branching. (A-F) The otIs138 transcriptional reporter was used to characterize the branching of PVD dendrites in the tail region, posterior to the PVD cell body, of wild-type worms at the L2 (A-C; L2′, L2′ and L2′′ refer to progressively later stages of development in L2 animals), L3 (D) and L4 (E) larval stages and at the young adult stage (F). Schematic representations of reporter labeling of PVD dendritic arbors are shown together with low (A,D-F) and high (A-F) magnification images of examples of the schematized projections. Red boxes in A and D-F represent the area shown in the high magnification image. Anteroposterior orientation is indicated by the white double-headed arrow. Asterisk in F denotes the spermatheca. The labeling of only one (left or right) PVD neuron and one of its dendritic trees is depicted in each schematic, and labeled PVD neuron cell bodies are identified by arrows in each of the middle panels. Scale bars: 10 μm.

RNAi can effectively knock down gene expression in PVD neurons

Given that both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous mechanisms are likely to control PVD dendrite development, it was imperative that our RNAi screens were capable of identifying genes that act in either PVD or the surrounding tissue (or both). To determine whether RNAi-mediated gene knockdown functions efficiently in PVD neurons, we attempted RNAi directly in the otIs138 PVD reporter. We found that GFP expression in PVD neurons was markedly reduced in otIs138 animals fed GFP dsRNA (Fig. 2A,B,D). Next, we fed mec-3 dsRNA to otIs138 animals, as mec-3 encodes a LIM homeobox transcription factor that is expressed, and probably functions autonomously, in PVD (Way and Chalfie, 1988; Way and Chalfie, 1989) to regulate the branching of its dendrites (Tsalik et al., 2003). Of the 127 animals treated with a mec-3 RNAi construct, 50% exhibited a reduced-branching phenotype similar to that displayed by mec-3 genetic mutants (Fig. 2C,E). Together, these observations indicate that our RNAi approach can be used to identify genes that act autonomously in PVD neurons.

Fig. 2.

RNAi constructs fed to wild-type worms efficiently knock down gene expression in PVD neurons. (A,B,D) otIs138 animals fed the empty vector construct, L4440, display minimal knockdown of GFP protein expression in PVD neurons (A); 96% of animals retain GFP expression in both PVD cell bodies (D). The green and red arrows in A point to labeled PVD and PDE cell bodies, respectively. otIs138 animals fed GFP dsRNA exhibit reduced GFP protein expression in PVD neurons (B); 28.3% of animals exhibit GFP expression in both PVD cell bodies, 41.3% express GFP in one PVD cell body only and 30.4% exhibit no GFP expression in both PVD cell bodies (D). The green arrow in B indicates the absence of GFP protein expression in a location presumably occupied by the PVD neuron. Because diminished GFP expression within PVD neurons prevented the visualization of PVD dendritic arbors (data not shown) in an RNAi hypersensitive strain (Schmitz et al., 2007), we conducted the complete screen in an otherwise wild-type background. (C,E) Half of otIs138 animals fed mec-3 dsRNA (C) display a significant reduction in the numbers of secondary, tertiary and quaternary dendrites (E), phenocopying the branch-reducing phenotype exhibited by mec-3(u298) genetic mutants. Anteroposterior orientation is indicated by the white double-headed arrow. The asterisks in A and C mark the spermatheca. Scale bars: 50 μm. Error bars represent s.e.m. ***P<0.001 determined by Fisher's exact test.

RNAi screens identify genes required for the formation of PVD dendritic arbors

To identify novel regulators of PVD dendrite development, we carried out both a small-scale candidate-based screen and a large-scale unbiased RNAi screen. In the candidate screen, we tested 121 genes known to regulate various aspects of neuronal development (Bülow et al., 2002; Kakimoto et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2007; Marshak et al., 2007; Miyashita et al., 2004; Schmitz et al., 2007; Struckhoff and Lundquist, 2003) or 16 PVD-specific genes (WormBase, release WS170, 02/09/07; see Table S1 in the supplementary material). In the large-scale screen, we individually knocked down 2693 genes on chromosome IV (Kamath et al., 2003). RNAi defects were categorized as either a qualitative increase or decrease in the number of dendrite branches. RNAi clones were classified as giving rise to positive effects if the overall percentage (average of three to five independent RNAi tests) of animals displaying a defective PVD arborization pattern was ≥20%. Based on these criteria, a total of 11 genes that either promote or suppress the formation of PVD dendrites were retrieved from the screens (Table 1). Interestingly, three of these genes, unc-116 (Patel et al., 1993; Sakamoto et al., 2005), dnc-1 (Koushika et al., 2004) and dli-1 (Koushika et al., 2004) encode proteins (kinesin-1 heavy chain, dynactin and dynein light intermediate chain, respectively) that regulate microtubule-based transport (Table 1), and homologs of another gene on this list, bicd-1, probably regulate minus end-directed microtubule-based transport together with several components of the dynein complex (Table 1) (Swan et al., 1999; Hoogenraad et al., 2001; Matanis et al., 2002; Hoogenraad et al., 2003). Given that a role for bicd-1 in the developing nervous system had not been previously characterized and the intriguing connection between bicd-1 and microtubule-based transport machinery, we focused our subsequent analyses on the role of bicd-1 in PVD dendrite arbor development.

bicd-1(ok2731) mutants phenocopy the bicd-1 RNAi-induced enhancement of PVD dendrite branching

Posterior to the PVD cell body (tail region), bicd-1 RNAi led to an increase in the number of ectopic tertiary dendrites along the length of the secondary dendrite (Fig. 3B-D). Quantification revealed that the number of ectopic tertiary dendrites per secondary dendrite was 0.18 in animals fed the empty vector L4440 and 0.9 in bicd-1 RNAi-treated animals (Fig. 3F). To confirm a requirement for bicd-1 in PVD dendrite branching, we analyzed a bicd-1 genetic mutant, ok2731. bicd-1(ok2731) mutants harbor a 547 bp deletion that eliminates exon 5 and results in the splicing of exon 4 to a cryptic splice site in the middle of exon 6, probably generating a truncated protein that retains partial function (Fig. 3A) (Fridolfsson et al., 2010). Notably, bicd-1(ok2731) mutant animals exhibited the same degree of enhanced branching as wild-type animals fed bicd-1 dsRNA (Fig. 3E,G) and first displayed the phenotype at the young adult stage (Fig. 3G). We also attempted to analyze the bicd-1(tm3421) allele, considered to be a genetic null (Fig. 3A) (Fridolfsson et al., 2010). However, owing to the high level of embryonic lethality associated with this allele (Fridolfsson et al., 2010), we were unable to recover young adult bicd-1(tm3421) homozygous animals. Cosmid rescue experiments were carried out to confirm that a mutation in the bicd-1 gene was responsible for the neuronal phenotype exhibited by bicd-1(ok2731) animals. Rescue was observed in five out of seven transgenic lines (see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). These findings, coupled with our observation that wild-type animals subjected to bicd-1 RNAi exhibited the identical enhanced-branching phenotype displayed by bicd-1(ok2731) mutant animals, provide strong evidence that bicd-1 function is required for the development of the elaborate branching pattern of PVD neurons.

Fig. 3.

bicd-1(ok2731) animals phenocopy the bicd-1 RNAi enhanced-branching defect. (A) Genetic position of bicd-1 on chromosome IV and its exon-intron structure, with the positions of the ok2731 and tm3421 mutations indicated. (B,C) Schematics of individual PVD dendrite trees present in wild-type (B) and bicd-1(ok2731) or bicd-1 RNAi-treated (C) animals. (D,E) otIs138 animals fed bicd-1 dsRNA exhibit an enhanced-branching phenotype posterior to the PVD cell body (D). bicd-1(ok2731) animals phenocopy the bicd-1 RNAi enhanced-branching phenotype (E). Purple arrowheads indicate ectopic tertiary dendrites. Asterisks indicate the spermatheca. Anteroposterior orientation is indicated by the white double-headed arrow. (F) Quantification of the enhanced-branching phenotype exhibited by otIs138 young adult animals subjected to bicd-1 RNAi. (G) The PVD enhanced-branching phenotype is first apparent at the young adult stage. n, number of secondary dendrites scored in F and G. Error bars represent s.e.m. ***P<0.001 determined by unpaired Student's t-test with Bonferroni adjustment. n.s., not significant. Scale bars: 10 μm.

bicd-1(ok2731) genetic mutants exhibit a reduced-branching phenotype distal to the PVD cell body

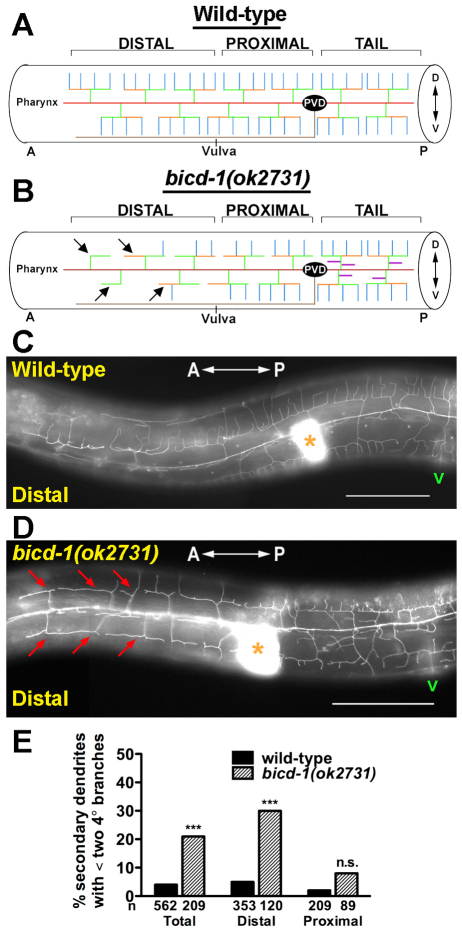

In Drosophila, mutations in components of the minus-end-directed dynein motor complex, Dynein light intermediate chain (Dlic) and short wing (sw), result in a decrease in terminal dendrite branching distal to the type IV dendritic arborization (da) neuron ddaC cell body (Satoh et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2008). Given the previously defined links between Bicaudal D and Dynein in Drosophila oogenesis (Swan et al., 1999) and mammalian cell culture systems (Hoogenraad et al., 2001; Hoogenraad et al., 2003; Matanis et al., 2002), we predicted that PVD arbors of bicd-1(ok2731) mutants would exhibit a reduction in the number of terminal branches distal to the PVD cell body. To test this hypothesis, the number of terminal branches (quaternary dendrites) was counted in both the distal and proximal regions of the PVD arbor (Fig. 4A). Individual dendritic trees possessing less than two quaternary dendrites were considered to exhibit a reduction in branch complexity (Fig. 4B). In wild-type animals, 5% of secondary dendrites analyzed in the distal portion of the PVD dendritic arbor exhibited a reduction in branch complexity (Fig. 4C,E). By contrast, 30% of secondary dendrites analyzed in the distal region of bicd-1(ok2731) PVD arbors displayed a reduction in branch complexity (Fig. 4D,E). Notably, this phenotype appeared to be restricted to the distal portion of the arbor as bicd-1(ok2731) mutant animals did not exhibit a statistically significant reduction in branch complexity proximal to the PVD cell body compared with wild-type animals (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

bicd-1(ok2731) animals exhibit a reduction in the number of dendritic branches distal to the PVD cell body. (A,B) Schematics of the wild-type (A) and bicd-1(ok2731) (B) PVD arborization pattern. `Distal' specifies the region of the PVD arbor anterior to the vulva and `proximal' denotes the region between the vulva and the PVD cell body. Arrows indicate individual dendritic trees that possess less than two quaternary dendrites. Dorsoventral orientation is indicated by the double-headed arrow. (C,D) Images of the distal regions of wild-type (C) and bicd-1(ok2731) (D) PVD arbors of young adult animals (52-58 hours post hatch, room temperature). Asterisks mark the spermatheca and `v' indicates the position of the vulva. Red arrows point to individual dendritic trees that possess less than two quaternary dendrites. (E) Quantification of the branch-reducing phenotype in both the distal and proximal regions of the PVD arbor. n, number of secondary dendrites scored. Error bars represent s.e.m. ***P<0.001 determined by chi-square test with Bonferroni adjustment. n.s., not significant. Scale bars: 50 μm.

bicd-1 acts in PVD neurons

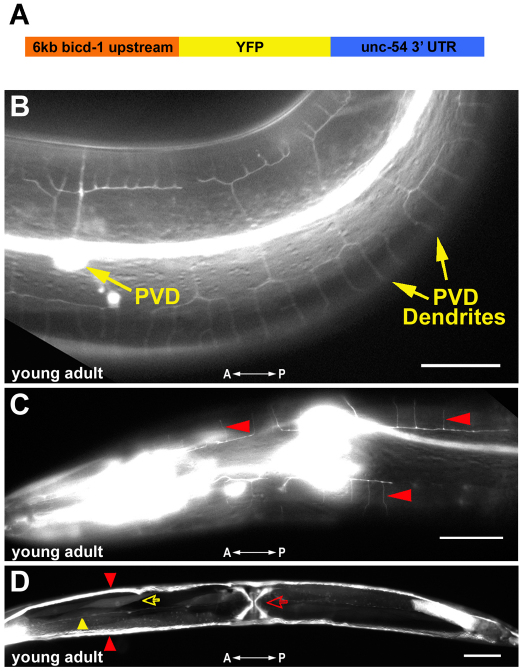

To gain insights into the expression pattern of bicd-1 and its possible site(s) of action, we generated a bicd-1 transcriptional reporter consisting of a 6 kb fragment directly upstream of the bicd-1 ATG start codon fused to the yfp/unc-54 3′UTR cassette (Fig. 5A). Robust bicd-1::YFP expression was observed in PVD neurons at the young adult stage, with the onset of expression in PVD first detectable at L4 (Fig. 5B; data not shown). bicd-1::YFP expression was also present in the H-shaped excretory cell, body wall muscle cells, vulva muscle cells and the AVF neuron (Fig. 5D). Notably, FLP neurons, which reside in the head and elaborate PVD-like dendritic arbors, also displayed bicd-1::YFP expression (Fig. 5C) and FLP dendrite arbors were malformed in bicd-1(ok2731) mutants (see Fig. S2 in the supplementary material). To determine the anatomical focus of action of bicd-1, we conducted cell type-specific rescue experiments and genetic mosaic analyses. In the cell type-specific rescue experiments, we investigated whether expression of bicd-1 cDNA under the control of either a PVD- or a muscle-specific promoter was capable of rescuing the mutant phenotype (Fig. 6A). Selective expression of BICD-1 in PVD neurons partially rescued the enhanced-branching phenotype in three out of four independent transgenic lines, whereas exclusively expressing BICD-1 in muscle cells only weakly rescued the enhanced-branching phenotype in one out of three independent transgenic lines (Fig. 6A and see Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). Furthermore, genetic mosaic analyses revealed that animals that retained wild-type bicd-1 in the AB.p lineage (which gives rise to the PVD neurons) but not the P1 lineage (which gives rise to 94 out of 95 body wall muscles) exhibited partial rescue of the enhanced-branching bicd-1(ok2731) mutant phenotype (Fig. 6B,C). Collectively, these studies support the view that bicd-1 acts primarily within PVD neurons to regulate the patterning of its dendritic arbors, but might also function in other cells (e.g. muscle).

Fig. 5.

bicd-1::YFP expression pattern. (A) A bicd-1 transcriptional reporter construct was generated by fusing 6kb of genomic sequence directly upstream of the bicd-1 ATG to the yfp/unc-54 3′UTR cassette. (B) Yellow arrows mark YFP protein expression detected in the PVD neuronal cell body and its dendrites at the young adult stage. (C) Red arrowheads point to labeled quaternary dendrites of FLP neurons in the head. (D) Ventral view of a bicd-1::YFP labeled animal. The red and yellow open arrows point to labeled vulva and body wall muscles, respectively. Red arrowheads identify YFP protein expression in the bilaterally symmetrical excretory canals and the yellow arrowhead points to YFP protein expression in the posteriorly directed processes of AVF neurons. Anteroposterior orientation is indicated by the white double-headed arrow. Scale bars: 25 μm in B and C; 50 μm in D.

Fig. 6.

bicd-1 acts in PVD neurons. (A) bicd-1 cDNA, expressed under the control of either the PVD specific promoter ser2prom3 or the muscle-specific promoter myo-3, partially rescues the enhanced-branched phenotype. (B) Mosaic analysis was conducted using a C43G2 cosmid rescuing line that exhibited complete rescue of the enhanced-branching phenotype (rzEx111, see Fig. S1 in the supplementary material). mec-7::gfp and myo-3::rfp were used to mark the AB.p and P1 lineages, respectively. b.w. muscle, body wall muscle. (C) Quantification of the enhanced-branching phenotype present in mosaic animals demonstrates that bicd-1 acts in PVD neurons. [AB.p+P1] denotes animals that have retained the array in both the AB and P1 lineages. [AB.p-] and [P1-] denote animals that have retained the array in either the P1 or AB.p lineage, respectively. Adult animals scored in the mosaic analyses were initially selected at the L4 stage and scored for rescue 24 hours later. n, number of secondary dendrites scored. Error bars represent s.e.m. **P<0.01 determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post test.

bicd-1 acts cooperatively with dhc-1 and unc-116

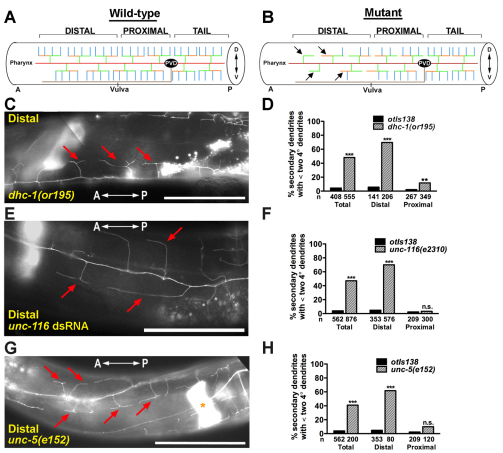

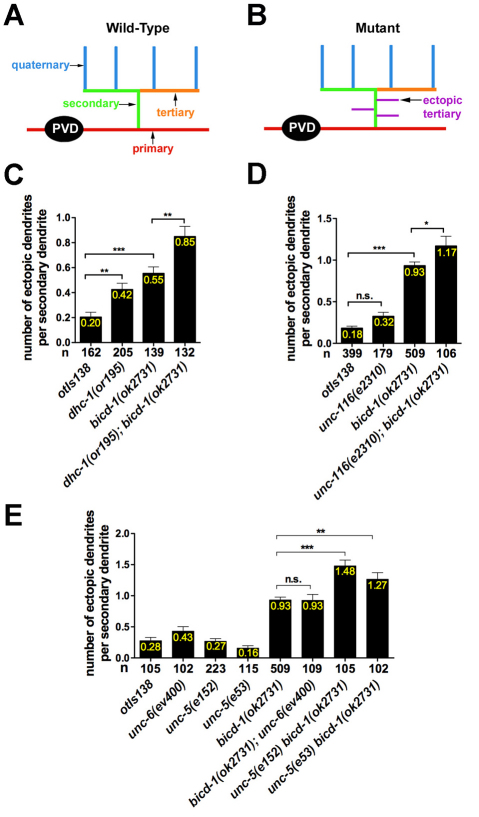

Our large-scale RNAi screen of chromosome IV identified two components of the C. elegans dynein motor complex, dynein light intermediate chain (dli-1) and dynactin (dnc-1), as probable regulators of PVD dendritic arbors (Table 1). Quantification of the enhanced-branching phenotype displayed by wild-type animals subjected to dli-1 or dnc-1 RNAi revealed that the number of ectopic tertiary dendrites per secondary dendrite was 1.05 (n=102) and 0.71 (n=86), respectively. Animals harboring a genetic mutation in another dynein complex component, dynein heavy chain (dhc-1), exhibited an enhanced-branching phenotype posterior to the PVD cell body and a reduced-branching phenotype distal to the PVD cell body (Fig. 7A-D and Fig. 8C). The similarities among the bicd-1, dli-1 and dnc-1 RNAi phenotypes and between the bicd-1 and dhc-1 genetic mutant phenotypes, raised the possibility that bicd-1 genetically interacts with components of the dynein complex to regulate the formation of PVD dendritic arbors. To test this hypothesis, we constructed and analyzed double mutants deficient in both bicd-1 and dhc-1. Posterior to the PVD cell body, dhc-1(or195);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutant animals exhibited a statistically significant increase in the number of ectopic tertiary dendrites per secondary dendrite (0.85) compared with the bicd-1(ok2731) single mutant (Fig. 8A-C). Because both the bicd-1(ok2731) and dhc-1(or195) alleles are hypomorphic alleles, these data indicate that bicd-1 and dhc-1 probably act cooperatively (either in the same pathway or in parallel pathways) to regulate PVD dendrite branching.

Fig. 7.

dhc-1(or195), unc-116(e2310) and unc-5(e152) mutants possess fewer dendrite branches distal to the PVD cell body. (A,B) Schematics of the wild-type (A) and mutant (B) PVD arborization pattern. `Distal' specifies the region of the PVD arbor anterior to the vulva and `proximal' denotes the region between the vulva and the PVD cell body. Arrows point to individual dendritic trees that possess less than two quaternary dendrites. (C,E,G) Micrographs of the distal regions of dhc-1(or195) (C), unc-116 RNAi (E) and unc-5(e152) (G) PVD arbors. Red arrows point to the absence of quaternary dendrites. The asterisk in G indicates the spermatheca. Anteroposterior orientation is indicated by the white double-headed arrow. (D,F,H) Quantification of the branch-reducing phenotype in the distal and proximal regions of the PVD arbor at 25°C (D) and 20°C (F,H). n, number of secondary dendrites scored. dhc-1(or195) mutants are temperature sensitive and all analyses utilizing this allele were performed at 25°C. Scale bars: 50 μm. Error bars represent s.e.m. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 determined by chi-square test with Bonferroni adjustment. n.s., not significant.

Fig. 8.

bicd-1 genetically interacts with dhc-1, unc-116 and unc-5 to regulate PVD dendrite branching. (A,B) Schematic depictions of individual PVD arbors present in wild-type (A) and mutant (B) animals. (C-E) Quantification of the enhanced-branching phenotype posterior to the PVD cell body (tail region) at 25°C (C) and 20°C (D,E). n, number of secondary dendrites scored. Error bars represent s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's post test. n.s., not significant.

Our candidate-based RNAi screen also identified unc-116, a component of the kinesin-1 plus-end-directed motor complex, as a regulator of PVD dendrite branching (Table 1). Consistent with the branching defects observed in unc-116 RNAi-treated animals, the unc-116(e2310) loss-of-function allele exhibited a reduced-branching phenotype in the distal region of the PVD dendritic arbor (Fig. 7E,F). A reduced-branching phenotype, however, was not observed proximal to the PVD cell body (Fig. 7F). Because unc-116(e2310) and bicd-1(ok2731) mutants each displayed a reduced-branching phenotype in the distal region of the PVD dendritic arbor, we constructed unc-116(e2310);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutants to determine whether unc-116 and bicd-1 act cooperatively to regulate the PVD arborization pattern. Although the reduced-branching phenotype in the distal region of the PVD arbor was not significantly enhanced in unc-116(e2310);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutants compared with the single mutants, we found that unc-116(e2310);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutants exhibited a statistically significant increase in the number of ectopic tertiary dendrites, posterior to the PVD cell body, compared with the bicd-1(ok2731) single mutant (Fig. 8D). Because both bicd-1(ok2731) and unc-116(e2310) are partial loss-of-function alleles, these data indicate that bicd-1 and unc-116 probably act cooperatively to regulate PVD dendrite branching, posterior to PVD cell bodies. Together, these double-mutant analyses indicate that bicd-1 acts cooperatively with genes encoding components of both minus- and plus-end microtubule-based motors to regulate distinct aspects of PVD dendrite development.

bicd-1 genetically interacts with the repulsive guidance receptor unc-5

Our candidate-based RNAi screen identified the repulsive guidance receptor unc-5 as a probable regulator of PVD dendrite branching, although our initial quantification of the defect revealed a relatively mild phenotype that placed unc-5 below our arbitrarily defined cut-off for positive clones. Consistent with the unc-5 RNAi phenotype, the unc-5(e152) loss-of-function allele displayed a reduced-branching phenotype in the distal region of the PVD arbor with 62% of the secondary dendrites analyzed elaborating less than two quaternary dendrites compared with 5% in wild-type animals (Fig. 7G,H). By contrast, a reduced-branching phenotype was not observed proximal to the PVD cell body (Fig. 7H). Notably, in the distal region, we observed that neither ventrally directed nor dorsally directed quaternary dendrites were present (Fig. 7G). Therefore, there was no bias (dorsal versus ventral) to the reduced-branching phenotype. Given the similarity between the bicd-1 and unc-5 mutant phenotypes, we constructed unc-5 bicd-1 double mutants harboring the unc-5(e53) null allele and the bicd-1(ok2731) allele. We found that unc-5(e53) bicd-1(ok2731) double mutants exhibited a robust increase in the number of ectopic tertiary dendrites (1.27) compared with the bicd-1(ok2731) single mutant (Fig. 8A,B,E). Next, we generated unc-5 bicd-1 double mutants using the unc-5(e152) allele. This allele is predicted to result in an UNC-5 C-terminal truncation that completely eliminates both the Z-D region and the `death domain', which are responsible for mediating the UNC-40-independent functions of UNC-5 (Killeen et al., 2002). Notably, the ectopic-branching phenotype of the unc-5(e152);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutants (1.48) was at least as severe as that observed in unc-5(e53);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutants (1.27) (Fig. 8E). This finding suggests that, in the context of PVD branching, the unc-5(e152) allele behaves as a complete loss-of-function allele. Moreover, it indicates that the C-terminal domain of UNC-5 may be crucial for the functional interaction between unc-5 and bicd-1. Although these double mutant data suggest that bicd-1 and unc-5 act in parallel pathways to regulate PVD branching, these data do not preclude the possibility that unc-5 and bicd-1 also act in the same pathway. Specifically, BICD-1 might aid in the transport of the UNC-5 guidance receptor (acting in the same pathway) along with a variety of additional cargoes (acting in a parallel pathway). We also asked whether unc-6, which encodes the netrin ligand for unc-5, interacts genetically with bicd-1. Unlike unc-5;bicd-1 double mutant animals, a complete loss of unc-6 did not enhance the bicd-1(ok2731) branching phenotype posterior to the PVD cell body (Fig. 8E). Collectively, these data suggest that unc-5 has a cryptic role in PVD dendrite development, which appears unc-6 independent.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we utilize C. elegans PVD neurons as a model system for studying dendritic branching. From candidate-based and unbiased RNAi screens we retrieved 11 genes that either promote or suppress the formation of PVD dendrites. We show, for the first time, that bicd-1 is involved in the development of dendritic branches; an impairment of bicd-1 function results in a distal-to-proximal shift of PVD dendrite branches. Furthermore, we find that knockdown of either dynein-dynactin or kinesin-1 microtubule-based motor complex components, produces similar PVD dendrite branching phenotypes and that bicd-1 acts cooperatively with dhc-1 and unc-116 to regulate the elaboration of PVD dendritic arbors. Lastly, we demonstrate a novel function for unc-5 in regulating PVD dendrite branching that appears to be independent of the ligand unc-6 and requires the cytoplasmic tail of UNC-5.

bicd-1: a novel regulator of dendrite branching

Bicaudal D was initially identified in Drosophila as a crucial regulator of anterior-posterior polarity during embryogenesis (Mohler and Wieschaus, 1986; Wharton and Struhl, 1989). More recent studies of Drosophila BicD and mammalian BICD1 and BICD2 have provided evidence that Bicaudal D homologs are coiled-coil proteins that function as accessory factors within the dynein-dynactin minus-end-directed motor complex (Hoogenraad et al., 2001; Hoogenraad et al., 2003; Matanis et al., 2002; Swan et al., 1999). In non-neuronal cells, Bicaudal D has been implicated as a key modulator of mRNA, organelle and lipid droplet transport as well as microtubule anchoring at the centrosome (Bullock and Ish-Horowicz, 2001; Fridolfsson et al., 2010; Fumoto et al., 2006; Larsen et al., 2008; Swan et al., 1999). In neurons, it has been found to play a role in retrograde transport in neurites of SK-N-SH cells (Wanschers et al., 2007), nuclear migration in Drosophila photoreceptor cells (Swan et al., 1999) and synaptic vesicle recycling at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (Li et al., 2010). In this study, we identify a novel role for the C. elegans homolog of Bicaudal D, bicd-1, in neuronal dendrite branching. Specifically, we show that both bicd-1 RNAi-treated animals and bicd-1 deletion mutants exhibit an enhanced PVD dendrite branching phenotype posterior and proximal to the PVD cell body, and a reduced-branching phenotype distal to PVD. Furthermore, both cell type-specific rescue experiments and genetic mosaic analyses suggest that bicd-1 acts primarily in PVD neurons.

A proposed mechanism for BICD-1 function

It has recently been shown that the minus-end-directed dynein motor complex has a key role in establishing the dendritic arborization pattern of class IV da neurons in Drosophila (Satoh et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2008). Specifically, mutations in the dynein complex components Dlic, sw and Dhc1, as well as a disruption in the function of the dynein-associated factors Lissencephaly-1 (Lis-1) and lava lamp (lva), result in a decrease in the number of terminal branches in the distal arbor and an increase in the number of ectopic branches in more proximal regions of the arbor (Satoh et al., 2008; Ye et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2008). Notably, the distribution of Golgi outposts (satellite Golgi cisternae that are required for dendritic growth and branching) exhibited a corresponding shift from a distal to a proximal position within dlic and Lva mutant dendritic arbors (Horton and Ehlers, 2003; Horton et al., 2005; Ye et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2008). Thus, the dynein motor complex might normally act to transport Golgi outposts within the dendritic arbor in order to facilitate the growth of dendritic branches (Zheng et al., 2008). Consistent with these observations, we find that the perturbation of dynein-associated bicd-1 or core components of the dynein motor complex results in an analogous distal-to-proximal shift in the distribution of PVD dendrite branches. Assuming that Golgi outposts are also present in C. elegans PVD dendrites, these phenotypic similarities raise the possibility that bicd-1, in conjunction with the dynein motor complex, is involved in the transport and localization of these specialized Golgi formations within PVD dendritic arbors. Like Drosophila Lva, mammalian BICD1 and BICD2 are coiled-coil golgin adaptors that also bind to dynein and dynactin and are localized to the Golgi network (Hoogenraad et al., 2001; Matanis et al., 2002). Furthermore, knockdown of mammalian BICD1 and BICD2 results in disruption of Golgi morphology (Fumoto et al., 2006). Given that there are no known C. elegans homologs of lva, it is tempting to speculate that C. elegans BICD-1 could function in a similar manner to Drosophila Lva to not only transport Golgi outposts but also preserve their morphology.

We also report that animals harboring a mutation in the kinesin heavy chain ortholog unc-116, just like bicd-1 and dhc-1 mutant animals, exhibit a reduced-branching phenotype distal to the PVD cell body. In addition, we show that the unc-116(e2310) mutation enhances the bicd-1(ok2731) enhanced-branching phenotype that is present posterior to the PVD cell body, leading us to conclude that unc-116 and bicd-1 act cooperatively to regulate the PVD dendrite branching pattern. In Drosophila class IV da neurons, it has been reported that animals mutant for Kinesin heavy chain (Khc) also exhibit dendritic branching defects identical to those observed in animals mutant for dynein complex components, raising the possibility that the kinesin motor might be responsible for transporting the dynein complex back to the cell body once dynein has unloaded its cargo (Satoh et al., 2008). Alternatively, we envisage a scenario in which the dynein and kinesin motors participate in bidirectional transport. Specifically, a single cargo would undergo net polarized transport along a single microtubule through the actions of the opposing motors (Welte, 2004). This bidirectional transport could allow for the navigation of cargo around obstacles (organelles, vesicles, etc.), thereby improving the efficiency of net transport (Welte, 2004). Recent evidence suggests that nuclear migration across C. elegans hyp7 embryonic hypodermal precursor cells is facilitated by the coordinated action of both dynein and kinesin-1 motors, with kinesin-1 acting to move nuclei forward and dynein acting to navigate obstacles by backward movements (Fridolfsson and Starr, 2010). Assuming that microtubules are oriented with their minus-ends distal in PVD neurons, as they are in Drosophila class IV neuronal dendritic arbors (Satoh et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2008), we speculate that dynein motors direct the forward transport of cargo into PVD dendrites (towards microtubule minus-ends), whereas kinesin-1 motors facilitate the navigation of cargo around the intracellular milieu via transport in the reverse direction (towards microtubule plus-ends). Specifically, in unc-116(e2310) mutants, the impaired kinesin-1 complex would be incapable of navigating cargo around obstacles in its path, thereby inhibiting the dynein complex from transporting cargo towards the periphery of the PVD dendritic arbor. This disruption of unc-116 function would lead to a PVD reduced-branching phenotype similar to that observed in bicd-1 and dynein mutants. In unc-116(e2310);bicd-1(ok2731) double mutant animals, both the ability to transport cargo in the anterograde direction and to navigate around obstacles would be perturbed, leading to an enhancement of the branching phenotype present in bicd-1(ok2731) animals posterior to the PVD cell body.

A novel role for unc-5 in regulating dendrite morphogenesis

C. elegans UNC-5 is a conserved repulsive guidance receptor that functions cell autonomously to mediate the dorsalward migration of cells and pioneer axons in an UNC-6-dependent fashion (Hamelin et al., 1993; Hedgecock et al., 1990; Leung-Hagesteijn et al., 1992; Su et al., 2000). We find that animals subjected to unc-5 RNAi or harboring the unc-5(e152) genetic mutation exhibit a reduced-branching phenotype distal to the PVD cell body. Although UNC-5 has not been previously implicated as a regulator of dendritic branching in any model system, it is interesting to note that vertebrate Unc5b can function as either an anti- (Lu et al., 2004) or pro-angiogenic (Navankasattusas et al., 2008) factor to regulate the branching of vasculature during embryonic development. In addition, Unc5b is localized to the tip and neck region of embryonic mouse distal lung endoderm during a period when lung epithelial tubes exhibit extensive branching (Dalvin et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2004).

Although the detailed mechanisms underlying the transport and subcellular localization of UNC-5 remain to be defined, it was recently reported that UNC-5::GFP is associated with small vesicles in DD and VD motor neuron axons and cell bodies (Ogura and Goshima, 2006). Together with our findings, this raises the possibility that the dynein motor complex within the PVD dendritic arbor transports UNC-5-containing vesicles. Notably, the unc-5(e152) allele harbors a non-sense mutation (Q507STOP) that results in truncation of the UNC-5 cytoplasmic domain at the beginning of the ZU-5 motif (Killeen et al., 2002). In addition, multiple dynein motors are required to transport a single cargo in vivo, and the recruitment of multiple dyneins to a single cargo is required for facilitating long distance transport in vitro (Mallik et al., 2005). Accordingly, the cytoplasmic domain of UNC-5 may be necessary for the recruitment of multiple dynein motors that would facilitate its long distance transport to the distal region of the PVD dendritic arbor. The cytoplasmic truncation associated with unc-5(e152) mutants might disrupt the recruitment of multiple motors, thereby limiting the distance that UNC-5 can be transported along PVD dendrites. Furthermore, PVD neurons extend primary dendritic process that run almost the entire length of the animal, with the anterior primary dendrite extending a significantly longer distance away from the PVD cell body than the posterior primary dendrite. A lack of UNC-5 at the distal-most segment of the anterior primary process (anterior to the vulva) may account for the significantly reduced (or lack of) dendritic branching in the distal region of the PVD arbor, as observed in unc-5(e152) mutants. Our double mutant analyses, using both the unc-5 loss-of-function allele e152 as well as the unc-5 molecular null allele e53, suggest that unc-5 and bicd-1 act cooperatively to regulate the branching pattern of PVD dendrites. Surprisingly, we find that a complete loss of unc-6, the netrin ligand for unc-5, did not enhance the bicd-1 PVD branching phenotype, suggesting that unc-5 might act independently of unc-6.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, the National Bioresource Project, the Sanger Institute, Ji Y. Sze (Albert Einstein College of Medicine), Oliver Hobert (Columbia University, NY, USA) and Sandhya Koushika (NCBS-TIFR) for strains and reagents; Peter Weinberg for DNA injection; Scott Clark (University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA), Wesley Grueber (Columbia University, NY, USA), Irini Topalidou (Columbia University, NY, USA) and Martin Chalfie (Columbia University, NY, USA) for insightful comments and advice; members of the Kaprielian (Nozomi Sakai, Ed Carlin, Arlene Bravo and Angela Jevince) and Bülow (Eillen Tecle, Matthew Attreed, Raja Bhattacharya, Janne Tornberg and Robert Townley) labs for helpful suggestions and critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R56NS038505, R01NS038505 (Z.K.) and 5R01HD055380 (H.E.B.), and C.A.-C. was supported by NIH training grant T32 GM07491. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.060939/-/DC1

References

- Ashrafi K., Chang F. Y., Watts J. L., Fraser A. G., Kamath R. S., Ahringer J., Ruvkun G. (2003). Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature 421, 268-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baens M., Marynen P. (1997). A human homologue (BICD1) of the Drosophila bicaudal-D gene. Genomics 45, 601-606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock S. L., Ish-Horowicz D. (2001). Conserved signals and machinery for RNA transport in Drosophila oogenesis and embryogenesis. Nature 414, 611-616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock S. L., Nicol A., Gross S. P., Zicha D. (2006). Guidance of bidirectional motor complexes by mRNA cargoes through control of dynein number and activity. Curr. Biol. 16, 1447-1452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bülow H. E., Berry K. L., Topper L. H., Peles E., Hobert O. (2002). Heparan sulfate proteoglycan-dependent induction of axon branching and axon misrouting by the Kallmann syndrome gene kal-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 6346-6351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzigeorgiou M., Yoo S., Watson J. D., Lee W. H., Spencer W. C., Kindt K. S., Hwang S. W., Miller D. M., III, Treinin M., Driscoll M., et al. (2010). Specific roles for DEG/ENaC and TRP channels in touch and thermosensation in C. elegans nociceptors. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 861-868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corty M. M., Matthews B. J., Grueber W. B. (2009). Molecules and mechanisms of dendrite development in Drosophila. Development 136, 1049-1061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvin S., Anselmo M. A., Prodhan P., Komatsuzaki K., Schnitzer J. J., Kinane T. B. (2003). Expression of Netrin-1 and its two receptors DCC and UNC5H2 in the developing mouse lung. Gene. Expr. Patterns 3, 279-283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M. K., Kostas S. A., Driver S. E., Mello C. C. (1998). Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806-811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser A. G., Kamath R. S., Zipperlen P., Martinez-Campos M., Sohrmann M., Ahringer J. (2000). Functional genomic analysis of C. elegans chromosome I by systematic RNA interference. Nature 408, 325-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson H. N., Starr D. A. (2010). Kinesin-1 and dynein at the nuclear envelope mediate the bidirectional migrations of nuclei. J. Cell Biol. 191, 115-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridolfsson H. N., Ly N., Meyerzon M., Starr D. A. (2010). UNC-83 coordinates kinesin-1 and dynein activities at the nuclear envelope during nuclear migration. Dev. Biol. 338, 237-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumoto K., Hoogenraad C. C., Kikuchi A. (2006). GSK-3beta-regulated interaction of BICD with dynein is involved in microtubule anchorage at centrosome. EMBO. J. 25, 5670-5682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueber W. B., Yang C. H., Ye B., Jan Y. N. (2005). The development of neuronal morphology in insects. Curr. Biol. 15, R730-R738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelin M., Zhou Y., Su M. W., Scott I. M., Culotti J. G. (1993). Expression of the UNC-5 guidance receptor in the touch neurons of C. elegans steers their axons dorsally. Nature 364, 327-330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton B., Dong Y., Shindo M., Liu W., Odell I., Ruvkun G., Lee S. S. (2005). A systematic RNAi screen for longevity genes in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 19, 1544-1555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser M., Spruston N., Stuart G. J. (2000). Diversity and dynamics of dendritic signaling. Science 290, 739-744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock E. M., Culotti J. G., Hall D. H. (1990). The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans. Neuron 4, 61-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O. (2002). PCR fusion-based approach to create reporter gene constructs for expression analysis in transgenic C. elegans. Biotechniques 32, 728-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad C. C., Akhmanova A., Howell S. A., Dortland B. R., De Zeeuw C. I., Willemsen R., Visser P., Grosveld F., Galjart N. (2001). Mammalian Golgi-associated Bicaudal-D2 functions in the dynein-dynactin pathway by interacting with these complexes. EMBO J. 20, 4041-4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogenraad C. C., Wulf P., Schiefermeier N., Stepanova T., Galjart N., Small J. V., Grosveld F., de Zeeuw C. I., Akhmanova A. (2003). Bicaudal D induces selective dynein-mediated microtubule minus end-directed transport. EMBO J. 22, 6004-6015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton A. C., Ehlers M. D. (2003). Dual modes of endoplasmic reticulum-to-Golgi transport in dendrites revealed by live-cell imaging. J. Neurosci. 23, 6188-6199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton A. C., Rácz B., Monson E. E., Lin A. L., Weinberg R. J., Ehlers M. D. (2005). Polarized secretory trafficking directs cargo for asymmetric dendrite growth and morphogenesis. Neuron 48, 757-771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan Y. N., Jan L. Y. (2010). Branching out: mechanisms of dendritic arborization. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 316-328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto T., Katoh H., Negishi M. (2006). Regulation of neuronal morphology by Toca-1, an F-BAR/EFC protein that induces plasma membrane invagination. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 29042-29053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Ahringer J. (2003). Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods 30, 313-321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Fraser A. G., Dong Y., Poulin G., Durbin R., Gotta M., Kanapin A., Le Bot N., Moreno S., Sohrmann M., et al. (2003). Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421, 231-237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killeen M., Tong J., Krizus A., Steven R., Scott I., Pawson T., Culotti J. (2002). UNC-5 function requires phosphorylation of cytoplasmic tyrosine 482, but its UNC-40-independent functions also require a region between the ZU-5 and death domains. Dev. Biol. 251, 348-366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Li C. (2004). Expression and regulation of an FMRFamide-related neuropeptide gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Comp. Neurol. 475, 540-550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J., Liu I. H., Song Y., Lee J. A., Halfter W., Balice-Gordon R. J., Linney E., Cole G. J. (2007). Agrin is required for posterior development and motor axon outgrowth and branching in embryonic zebrafish. Glycobiology 17, 231-247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koushika S. P., Schaefer A. M., Vincent R., Willis J. H., Bowerman B., Nonet M. L. (2004). Mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans cytoplasmic dynein components reveal specificity of neuronal retrograde cargo. J. Neurosci. 24, 3907-3916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen K. S., Xu J., Cermelli S., Shu Z., Gross S. P. (2008). BicaudalD actively regulates microtubule motor activity in lipid droplet transport. PLoS ONE 3, e3763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung-Hagesteijn C., Spence A. M., Stern B. D., Zhou Y., Su M. W., Hedgecock E. M., Culotti J. G. (1992). UNC-5, a transmembrane protein with immunoglobulin and thrombospondin type 1 domains, guides cell and pioneer axon migrations in C. elegans. Cell 71, 289-299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Kuromi H., Briggs L., Green D. B., Rocha J. J., Sweeney S. T., Bullock S. L. (2010). Bicaudal-D binds clathrin heavy chain to promote its transport and augments synaptic vesicle recycling. EMBO J. 29, 992-1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Stein E., Oliver T., Li Y., Brunken W. J., Koch M., Tessier-Lavigne M., Hogan B. L. M. (2004). Novel role for netrins in regulating epithelial behavior during lung branching morphogenesis. Curr. Biol. 14, 897-905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., le Noble F., Yuan L., Jiang Q., de Lafarge B., Sugiyama D., Breant C., Claes F., De Smet F., Thomas J. L., et al. (2004). The netrin receptor UNC5B mediates guidance events controlling morphogenesis of the vascular system. Nature 432, 179-186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallik R., Petrov D., Lex S. A., King S. J., Gross S. P. (2005). Building complexity: an in vitro study of cytoplasmic dynein with in vivo implications. Curr. Biol. 15, 2075-2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshak S., Nikolakopoulou A. M., Dirks R., Martens G. J., Cohen-Cory S. (2007). Cell-autonomous TrkB signaling in presynaptic retinal ganglion cells mediates axon arbor growth and synapse maturation during the establishment of retinotectal synaptic connectivity. J. Neurosci. 27, 2444-2456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matanis T., Akhmanova A., Wulf P., Del Nery E., Weide T., Stepanova T., Galjart N., Grosveld F., Goud B., De Zeeuw C. I., et al. (2002). Bicaudal-D regulates COPI-independent Golgi-ER transport by recruiting the dynein-dynactin motor complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 986-992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyashita T., Yeo S. Y., Hirate Y., Segawa H., Wada H., Little M. H., Yamada T., Takahashi N., Okamoto H. (2004). PlexinA4 is necessary as a downstream target of Islet2 to mediate Slit signaling for promotion of sensory axon branching. Development 131, 3705-3715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler J., Wieschaus E. F. (1986). Dominant maternal-effect mutations of Drosophila melanogaster causing the production of double-abdomen embryos. Genetics 112, 803-822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navankasattusas S., Whitehead K. J., Suli A., Sorensen L. K., Lim A. H., Zhao J., Park K. W., Wythe J. D., Thomas K. R., Chien C. B., et al. (2008). The netrin receptor UNC5B promotes angiogenesis in specific vascular beds. Development 135, 659-667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura K., Goshima Y. (2006). The autophagy-related kinase UNC-51 and its binding partner UNC-14 regulate the subcellular localization of the Netrin receptor UNC-5 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 133, 3441-3450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren-Suissa M., Hall D. H., Treinin M., Shemer G., Podbilewicz B. (2010). The fusogen EFF-1 controls sculpting of mechanosensory dendrites. Science 328, 1285-1288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel N., Thierry-Mieg D., Mancillas J. R. (1993). Cloning by insertional mutagenesis of a cDNA encoding Caenorhabditis elegans kinesin heavy chain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90, 9181-9185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto R., Byrd D. T., Brown H. M., Hisamoto N., Matsumoto K., Jin Y. (2005). The Caenorhabditis elegans UNC-14 RUN domain protein binds to the Kinesin-1 and UNC-16 complex and regulates synaptic vesicle localization. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 483-496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh D., Sato D., Tsuyama T., Saito M., Ohkura H., Rolls M. M., Ishikawa F., Uemura T. (2008). Spatial control of branching within dendritic arbors by dynein-dependent transport of Rab5-endosomes. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1164-1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz C., Kinge P., Hutter H. (2007). Axon guidance genes identified in a large-scale RNAi screen using the RNAi-hypersensitive Caenorhabditis elegans strain nre-1(hd20) lin-15b(hd126). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 834-839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C. J., Watson J. D., Spencer W. C., O'Brien T., Cha B., Albeg A., Treinin M., Miller D. M., III (2010). Time-lapse imaging and cell-specific expression profiling reveal dynamic branching and molecular determinants of a multi-dendritic nociceptor in C. elegans. Dev. Biol. 345, 18-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struckhoff E. C., Lundquist E. A. (2003). The actin-binding protein UNC-115 is an effector of Rac signaling during axon pathfinding in C. elegans. Development 130, 693-704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M., Merz D. C., Killeen M. T., Zhou Y., Zheng H., Kramer J. M., Hedgecock E. M., Culotti J. G. (2000). Regulation of the UNC-5 netrin receptor initiates the first reorientation of migrating distal tip cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 127, 585-594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter B., Romberg L. M., Steward R. (1989). Bicaudal-D, a Drosophila gene involved in developmental asymmetry: localized transcript accumulation in ovaries and sequence similarity to myosin heavy chain tail domains. Genes Dev. 3, 1957-1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan A., Nguyen T., Suter B. (1999). Drosophila Lissencephaly-1 functions with Bic-D and dynein in oocyte determination and nuclear positioning. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 444-449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsalik E. L., Niacaris T., Wenick A. S., Pau K., Avery L., Hobert O. (2003). LIM homeobox gene-dependent expression of biogenic amine receptors in restricted regions of the C. elegans nervous system. Dev. Biol. 263, 81-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanska M., Blazejczyk M., Jaworski J. (2008). Molecular Basis of Dendrite Arborization. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. (Wars.) 68, 264-288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanschers B. F. J., van de Vorstenbosch R., Schlager M. A., Splinter D., Akhmanova A., Hoogenraad C. C., Wieringa B., Fransen J. A. M. (2007). A role for the Rab6B Bicaudal-D1 interaction in retrograde transport in neuronal cells. Exp. Cell Res. 313, 3408-3420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way J. C., Chalfie M. (1988). mec-3, a homeobox-containing gene that specifies differentiation of the touch receptor neurons in C. elegans. Cell 54, 5-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way J. C., Chalfie M. (1989). The mec-3 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans requires its own product for maintained expression and is expressed in three neuronal cell types. Genes Dev. 3, 1823-1833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welte M. A. (2004). Bidirectional transport along microtubules. Curr. Biol. 14, R525-R537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton R. P., Struhl G. (1989). Structure of the Drosophila BicaudalD protein and its role in localizing the posterior determinant nanos. Cell 59, 881-892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters N. M., MacKeigan J. P. (2008). From sequence to function: using RNAi to elucidate mechanisms of human disease. Cell Death Differ. 15, 809-819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yassin L., Gillo B., Kahan T., Halevi S., Eshel M., Treinin M. (2001). Characterization of the DEG-3/DES-2 receptor: a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor that mutates to cause neuronal degeneration. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 17, 589-599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye B., Zhang Y., Song W., Younger S. H., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. (2007). Growing dendrites and axons differ in their reliance on the secretory pathway. Cell 130, 717-729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Wildonger J., Ye B., Zhang Y., Kita A., Younger S. H., Zimmerman S., Jan L. Y., Jan Y. N. (2008). Dynein is required for polarized dendritic transport and uniform microtubule orientation in axons. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1172-1180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]