Abstract

Background

Glucose tolerance can be assessed noninvasively using 13C-labeled glucose added to a standard oral glucose load, by measuring isotope-enriched CO2 in exhaled air. In addition to the clear advantage of the noninvasive measurements, this approach may be of value in overcoming the high variability in blood glucose determination.

Methods

We compared within-individual variability of breath CO2 isotope enrichment with that for blood glucose in a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) by adding 150 mg of d-[13C]glucose (13C 99%) to a standard 75-g glucose load. Measurements of whole blood glucose (by glucose oxidase) and breath isotope enrichment (by isotope ratio mass spectrometry) were made every 30 min for 3 h. Subjects underwent three repeat tests over a 3-week period. Values for variability of breath isotope enrichment at 3 h (∂‰180) and of area under the curve for enrichment to 180 min (AUC180) were compared with variability of the 2-h OGTT blood glucose.

Results

Breath test-derived measures exhibited lower within-subject variability than the 2-h OGTT glucose. The coefficient of variation for ∂‰180 was 7.4 ± 3.9% (mean ± SD), for AUC180 was 9.4 ± 6.3%, and for 2-h OGTT blood glucose was 13 ± 7.1% (P = 0.005 comparing ∂‰180 versus 2-h blood glucose; P = 0.061 comparing AUC180 versus 2-h blood glucose; P = 0.03 comparing ∂‰180 versus AUC180).

Conclusions

Breath test-derived measurements of glucose handling had lower within-subject variability versus the standard 2-h blood glucose reading used in clinical practice. These findings support further development of this noninvasive method for evaluating glucose tolerance.

Introduction

The dynamic response to an oral glucose load has historically been the gold standard for diagnosing not only diabetes mellitus but also intermediate forms of metabolic dysfunction (e.g., impaired glucose tolerance).1 This response reflects the acute interplay among beta-cell responsiveness, insulin-induced suppression of hepatic glucose output, and insulin-stimulated disposal of glucose into insulin-sensitive tissues. The main limiting factors in the application of dynamic glucose tolerance testing have been the requirement for repeated blood samples and high biological variability in the 2-h blood glucose measurement.1–3

The 13C-glucose breath test is a novel noninvasive technique for the assessment of glucose homeostasis.4,5 In this approach, nonradioactive isotopically labeled d-glucose ([13C]glucose) is added to a standard 75-g glucose load. Following tissue glucose uptake and cellular metabolism, appearance of labeled CO2 in exhaled breath can be measured to determine breath CO2 isotope enrichment.

One of the recognized disadvantages of the standard oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) is its high variability. The objective of this study was to evaluate within-subject repeatability of breath test-derived indices of glucose tolerance in comparison with the 2-h OGTT blood glucose measurement.

Research Design and Methods

Subjects

We recruited healthy subjects without diabetes who were lean (body mass index [BMI] ≤25 kg/m2) or obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and obese type 2 diabetes subjects. Subjects were included from across the full range of glycemia in order to assess variability in both normoglycemic and dysglycemic populations. Subjects were excluded for any of the following reasons: BMI >40 kg/m2; use of any medication known to affect glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, or inflammation (except antidiabetes medications used by subjects with diabetes); known acromegaly, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus infection, hypercortisolism or hypocortisolism, or other medical condition with recognized impact on glucose metabolism; current smoking of cigarettes or cigars; pregnancy; or routine exercise more than two times per week. Subjects were recruited by printed advertisement from the general population. We screened 23 subjects in order to enroll 20 subjects, divided a priori into phenotypic groups as above. The study was conducted at Indiana University School of Medicine (Indianapolis, IN) and was approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board. All subjects provided written informed consent before participation.

[13C]Glucose breath test/2-h OGTT

We undertook three identical isotopically labeled OGTTs in each subject. Repeat tests were performed within 2 weeks of the preceding test (with one exception). Food consumption was ad libitum prior to testing. On study days, following at least a 12-h fast, subjects were admitted to the Indiana University CTSI Clinical Research Center by 0700 h. An antecubital venous catheter was placed in the nondominant arm for the collection of blood samples. Prior to blood/breath sampling, weight and height were measured using standardized instruments.

After samples were obtained for baseline fasting glucose and insulin values (at t = −15 and 0 min), each subject was given a standard 75-g glucose solution containing 150 mg of [U-13C]glucose ([13C]glucose at all six positions; catalog number CLM-1396, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, MA) at t = 0 min. Blood glucose concentrations were checked every 30 min over a 2-h interval. Breath samples were obtained at the following time points: −15, 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min. Each breath sample was obtained by having subjects exhale into a standard test tube (Exetainer®, Labco, High Wycombe, UK) using a common straw. Filled test tubes were immediately stoppered with a screw-on sealing cap and stored away from light until measured. These tubes are known to be impermeable to gases for up to 90 days after sealing.

Breath CO2-derived measurements

The ratio of 13CO2 to 12CO2 was analyzed using continuous flow isotope ratio mass spectrometry (Europa Scientific 20-20 infrared mass spectrometer, Europa Scientific Ltd., Crewe, UK). This device samples directly from the sealed tube, preventing contamination from room air. Results were reported as per mille change (‰) in 13CO2 abundance from baseline and expressed as change over baseline (∂‰). Area under the curve for enrichment to 180 min (AUC180) for this measurement was calculated by the trapezoidal rule.

In insulin-resistant states glucose-derived CO2 production is impaired because of reduced insulin-stimulated glucose uptake and oxidation. Furthermore, glucose oxidation (Gox) is reduced relative to lipid oxidation (Lox).6 The ratio of Gox to Lox as a measure of integrated fuel metabolism has been shown to be more sensitive than the 2-h OGTT glucose measurement in detecting prediabetes.6 Breath enrichment is inversely proportional to the ratio of Lox to Gox (see Appendix); Lox/Gox was calculated as 1/[AUC180 × 1,000].

Blood analyses

Whole blood glucose concentrations were determined using a glucose oxidase-based bedside glucose analyzer (YSI model 1500, Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Plasma insulin measurements were made using a radioimmune assay specific for human insulin and with cross-reactivity with pro-insulin <0.2% (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Nonesterified fatty acids were measured using a colorimetric assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Statistical analysis

All results were expressed as mean ± SD values. One-way analysis of variance was used to compare variables across study population subgroups. Within-subject repeatability was assessed primarily as the coefficient of variation (CV) calculated from the three repeat tests for each subject for each testing end point. Paired t tests were used to compare the CV for 2-h OGTT blood glucose against that for each breath test-derived variable; we also compared the variability of the testing methods with each other. Root mean squared CV (RMS-CV) values were calculated for each of the test end points, as an index of average variability across the whole study group.

Bland-Altman plots were constructed to assess the magnitude and distribution of test–retest differences. The intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated as a measure of the portion of total measurement variability caused by variation between subjects. Statistical testing was performed using PASW Statistics version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

We studied eight lean subjects without diabetes, six obese subjects without diabetes, and six obese type 2 diabetes subjects. Nineteen of the 20 subjects underwent three repeat tests over a 3-week period; for one subject the third test was 8 weeks after his second test. Weight and other metabolic parameters were unchanged across the testing interval (data not shown).

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. There were 12 men and eight women in the study. Men ranged in age from 23 to 66 years (mean ± SD, 42.4 ± 15.6 years), whereas women ranged in age from 22 to 56 years (45.4 ± 12 years) (P = not significant comparing age across sex). BMI for men was in the range 21.4–44.0 kg/m2 (28.6 ± 7.2 kg/m2); for women the value was 27.8–45.7 kg/m2 (34.3 ± 6.1 kg/m2) (P = 0.08 comparing BMI across sex).

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Characteristic | All (n = 20) | Lean (n = 8) | Obese (n = 6) | T2DM (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-h OGTT blood glucose (mmol/L) | 8.8 ± 4.2 | 6.7 ± 1.4 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 14.2 ± 3 |

| Age (years) | 43 ± 14.2 | 32 ± 12 | 47 ± 9 | 54 ± 11 |

| Gender (M/F) | 13/7 | 6/2 | 1/5 | 6/0 |

| Weight (kg) | 91.9 ± 21.6 | 78.4 ± 8.8 | 101.5 ± 11.3 | 100.5 ± 32.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.4 ± 7.3 | 24.9 ± 2.5 | 36 ± 5.3 | 32.2 ± 8 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 7.3 ± 2.1 |

| Fasting insulin (mU/L) | 16 ± 10.5 | 12 ± 5.2 | 14.7 ± 5.9 | 22.3 ± 15 |

| Fasting FFA (mM) | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

Data are mean ± SD values.

BMI, body mass index; FFA, free fatty acids; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Data for the evaluated testing end points are presented in Table 2. All test measurements were significantly different across the three subgroups (by analysis of variance; P values shown in Table 2). The 2-h OGTT blood glucose was significantly higher for subjects with diabetes compared to lean subjects (P < 0.001) with no significant difference between lean and obese individuals. Similar trends were noted for other breath test-derived variables: ∂‰180 was significantly lower in DM versus lean (P = 0.03) with no difference noted between lean and obese subjects (P = 0.84), AUC180 values were lower in subjects with diabetes compared to lean subjects (P = 0.02) with no difference between lean and obese subjects, and Lox/Gox was significantly higher in subjects with diabetes versus lean subjects (P = 0.02) and again not different between lean and obese subjects.

Table 2.

Mean Values for 2-h Oral Glucose Tolerance Test Glucose and Breath-Derived Tests, by Group

| Test type | All subjects | Lean | Obese | T2DM | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-h OGTT glucose (mmol/L) | 8.8 ± 4.2 | 6.7 ± 1.4 | 6.2 ± 1.5 | 14.2 ± 3.3** | <0.001 |

| δ180 (‰) | 47.5 ± 11.5 | 53 ± 10.5 | 49.9 ± 7.8 | 37.8 ± 10.9* | 0.03 |

| AUC180 (‰ × min) | 4,189.7 ± 1,158.4 | 4,752.6 ± 922.9 | 4,418.6 ± 1,072 | 3,210.2 ± 1,018* | 0.03 |

| Lox/Gox (1/[‰ × min]) | 237.2 ± 84.8 | 196 ± 35.8 | 216.5 ± 54.7 | 312 ± 111.5* | 0.02 |

Data are mean ± SD values.

P < 0.05, **P < 0.0005 versus lean group.

AUC180, area under the curve for enrichment to 180 min; δ180, change at 180 min; Lox/Gox, ratio of lipid oxidation to glucose oxidation; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Within-subject variability data are presented in Table 3. We observed lower within-subject variability for the 2-h OGTT blood glucose than is generally reported (observed CV 13.3 ± 7.3%).2,3 The premise of our design was that breath testing would have lower within-subject variability than 2-h OGTT blood glucose; hence the primary analysis was to compare the CV for each breath test against that of the 2-h OGTT blood glucose in a pairwise manner (Table 3). The within-subject variability of the 2-h OGTT blood glucose was higher than that of ∂‰180 (P = 0.005) and that of Lox/Gox (P = 0.048); the mean within-subject CV for AUC180 was not statistically different from that of the 2-h OGTT blood glucose (P = 0.061). Comparisons within the various breath test-derived measurements revealed significantly lower variability in ∂‰180 compared to AUC180 (P = 0.03) and Lox/Gox (P = 0.03), but no difference in CV between Lox/Gox and AUC180 (P = 0.23). Within-subject repeatability did not differ significantly across subject groups for any of the testing end points (Table 3).

Table 3.

Within-Subject Variability for 2-h Oral Glucose Tolerance Test Glucose and Breath-Derived Tests

| |

Lean |

Obese |

T2DM |

All subjects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | CV | RMS-CV | CV | RMS-CV | CV | RMS-CV | CV | RMS-CV |

| 2-h OGTT (mg/dL) | 16.6 ± 8.2% | 18.3 | 10.3 ± 6% | 11.7 | 10.9 ± 5.2% | 11.9 | 13 ± 7.1%bd | 14.8 |

| δ180 (‰) | 5.3 ± 2.0% | 5.6 | 7.6 ± 5.2% | 8.9 | 10 ± 3.2% | 10.4 | 7.4 ± 3.9%acd | 8.3 |

| AUC180 (‰ × min) | 6.5 ± 3.6% | 7.3 | 9.2 ± 8.9% | 12.3 | 13.5 ± 4.3% | 14.1 | 9.4 ± 6.3%b | 11.2 |

| Lox/Gox | 6.5 ± 3.5% | 7.3 | 8.7 ± 8.3% | 11.6 | 13.3 ± 4.5% | 14 | 9.2 ± 6%ab | 11 |

Data are mean ± SD values.

Comparisons of coefficient of variationvalues across tests are presented in the second to last column for all subjects; superscripts indicate P < 0.05 comparing against a2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) blood glucose, bchange at 180 min (δ180), carea under the curve for enrichment to 180 min (AUC180), or dratio of lipid oxidation to glucose oxidation (Lox/Gox).

CV, coefficient of variation; RMS-CV, root mean squared CV; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus.

RMS-CV was calculated for each test using the whole study group and for each of the subgroups (Table 3). Concordant with the raw CV data, RMS-CV for 2-h OGTT blood glucose was systematically higher than for all breath test-derived measurements. These single-value population averages are not suitable for statistical comparisons. However, the pattern is consistent with the significant differences observed with calculations based on the CV values directly.

Intraclass correlation coefficients for the breath test variables were found to be high and not different across groups (for ∂‰180 = 0.962; for AUC180 = 0.941; for Lox/Gox = 0.964; and for 2-h OGTT blood glucose = 0.972). These values indicate that in this population the between-subject variability is large compared to the within-subject variability for all measurement approaches.

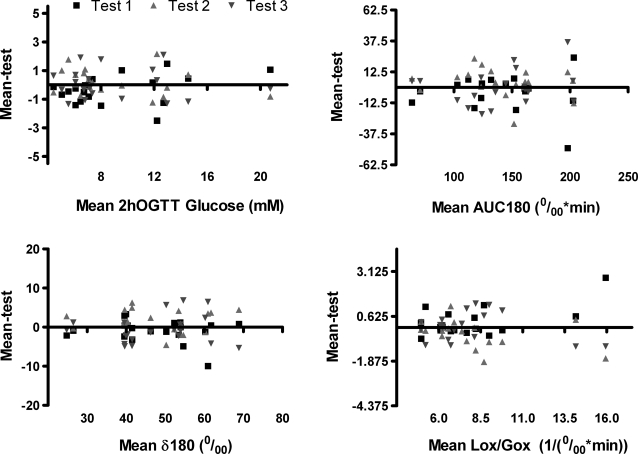

Bland-Altman plots for these tests are shown in Figure 1. These graphs show the distribution of individual repeat measurements for respective tests plotted against the mean of all three measurements for any given individual. (In order for the plots to be visually comparable across tests, for all plots the y-axis range is ± 25% of the upper limit of the x-axis.)

FIG. 1.

Bland-Altman plots for the test end points evaluated. The y-axes are scaled at 25% of the x-axis range for each plot, so that the plots are visually comparable. AUC180, area under the curve for enrichment to 180 min; δ180, change at 180 min; Lox/Gox, ratio of lipid oxidation to glucose oxidation; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

The distribution of data was not heteroscedastic for ∂‰180 or Lox/Gox and only mildly so for AUC180. It is apparent from this presentation that the data for the ∂‰180 measurements were the least variable, consistent with the CV calculations presented above. Other breath test variables at best modestly improved in comparison to the 2-h OGTT glucose measurement.

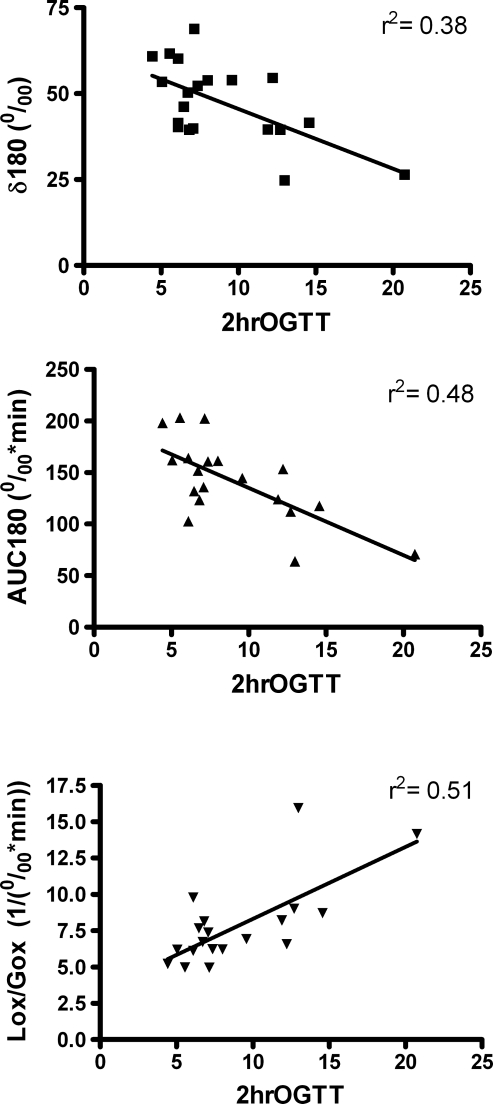

In Figure 2 we present correlation plots comparing the breath test end points and 2-h OGTT blood glucose measurement. The correlation coefficients are shown on the respective graphs. Importantly, the breath variables were linearly related with the blood glucose measurement across the range of values observed in this population.

FIG. 2.

Correlation plots comparing the 2-h oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) blood glucose reading with the breath test end points, demonstrating linearity across the wide range of values observed in this study population. AUC180, area under the curve for enrichment to 180 min; δ180, change at 180 min; Lox/Gox, ratio of lipid oxidation to glucose oxidation.

Discussion

We have compared the within-subject variability of breath test-derived indices of glucose tolerance with that of the standard 2-h OGTT plasma glucose. We found that the within-subject variability of breath isotope measurement at 180 min after glucose ingestion was significantly lower than that of the 2-h plasma glucose. Other breath test-derived indices also exhibited lower within-subject variability than the blood glucose values but were themselves inferior to the 180-min breath test reading (∂‰180). All breath test end points showed comparable proportion of total variability attributable to between-subject differences (as indicated by the intraclass coefficient) as for the 2-h OGTT glucose. The breath test values were linearly related with 2-h OGTT plasma glucose readings. Therefore, in addition to the advantage of being noninvasive, breath test measurements exhibit improved within-subject variability compared to blood sampling-based measures of the dynamic response to oral glucose loading.

Lewanczuk et al.4 first demonstrated validity of the 13C-labeled glucose breath test by comparing it with hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp-derived variables in a group of 26 subjects of varying degrees of insulin sensitivity. Breath test-derived CO2 enrichment was found to have a significant correlation (r = 0.69, P = 0.0001) with the clamp-derived insulin sensitivity index, comparable to the magnitude of correlation seen between insulin sensitivity index and QUICKI (r = 0.78) and homeostasis assessment model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (r = −0.60) reported previously.7 Dillon et al.5 have demonstrated clinical usefulness of a standard breath analyzer to detect differences in breath CO2 excretion between normal individuals and those with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes. The glucose breath test was able to detect marked differences in breath CO2 kinetics within a 3.5–4.5-h time period, i.e., within the time frame of a standard OGTT. In another recent study the breath test has been evaluated in the pediatric population.8 In prepubertal obese children, a moderate correlation was noted between [13C]glucose breath test and other surrogate indices of insulin resistance such as QUICKI (r = 0.53, P = 0.01), HOMA-IR (r = −0.51, P = 0.01), and fasting insulin (r = −0.5, P = 0.01). With the current study we have demonstrated superior repeatability of breath testing compared to OGTT blood glucose measurement. Overall, this line of evidence supports the potential utility of labeled glucose breath tests for the evaluation of glucose tolerance and metabolic status. Further testing and development for specific testing indications are warranted. For example, this method may be of particular value in clinical application for screening for gestational diabetes, and because this test reflects cellular fuel oxidation in addition to insulin-driven components of glucose disposal, the test may be of value as tool for studies of insulin resistance.

Advantages and disadvantages

Oral glucose tolerance testing has been the gold standard method of assessing metabolic status for decades. The principal advantages are the long history of using this test, with clearly defined thresholds for diagnosis of diabetes and prediabetes states and known relationships between OGTT responses and risk of diabetes outcome. However, this approach has many well-recognized disadvantages. Among these is the inconvenience for both the patient and the testing facility, due to the requirement to have repeated blood samples taken over the time course of the test, and the very high within-subject variability of the 2-h blood glucose (variously estimated as 12–16%2,3).

The American Diabetes Association and others have recently adopted glycated hemoglobin measurement for the diagnosis of diabetes. The main advantages of this approach are that this measurement is less sensitive to day-to-day variation in an individual's metabolic response and it is much more convenient for the patient and for the testing facility. Also, because this test reflects a time-averaged glucose exposure, test–retest variability due to biological variability is less of a problem, and again the relationship of glycated hemoglobin level with risk of diabetes outcomes is well established. The time-integrated nature of this measurement is a disadvantage where information about the acute capacity to respond to a metabolic stressor is needed and where important changes in physiology may be taking place more quickly than can be reflected in the average level of glycation. Also, the glycated hemoglobin level provides essentially no information about insulin sensitivity. There will therefore continue to be a need for dynamic metabolic testing in both the clinical and research fields.

Compared with the 2-h OGTT blood glucose reading, the breath test version of the OGTT has a number of desirable features. Because of its completely noninvasive nature, it is very acceptable to patients and is easily applied in an office or clinic setting. In the current analyses a single sample taken 180 min after the glucose load is the preferred measurement from the perspective of test–retest variability. Because this testing requires only a breath sample collection this can be readily done outside of the testing facility, perhaps even allowing patients to return home or to work with a standard straw and test tube for use at the designated time. Although we used gas isotope ratio mass spectrometry in the current testing, isotopically enriched CO2 can also be easily measured with a simple infrared analyzer.5 Therefore many features of this approach make it feasible and superior to blood sampling-based oral glucose tolerance testing, while maintaining the advantages of a performing dynamic test.

Future applications of breath testing for glucose tolerance

The most obvious application of this methodology is as an alternative approach for the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Even in the current sample, involving only a small sample of subjects across the spectrum of glycemic control, we were readily able to statistically distinguish subjects with diabetes. The glycated hemoglobin value is likely to become the mainstream approach for diabetes diagnosis. However, there will be circumstances where alternatives are needed, and breath testing may provide compelling advantages in these circumstances. For example, in screening for gestational diabetes mellitus integrated measures of glycemic exposure are simply inadequate, and here the breath testing approach may prove to be a viable alternative to traditional blood sample-based testing. With its potential utility in pediatric populations, it is particularly attractive for clinical or research use in settings (schools, community clinics) where venipuncture is logistically unworkable and impractical.

Prior work by others suggests that breath testing is sensitive to prediabetes levels of dysglycemia, and in our data we observed a linear relationship between breath and blood measures across the range of glycemia. Together these observations suggest that the breath test can also distinguish gradations of glycemic status in the nondiabetes range. Further studies evaluating the behavior of this test in such populations are therefore of value. Potential applications here include identification of prediabetes levels of metabolic dysfunction, for example, in screening for preventive interventions.

An important feature of breath testing compared to blood glucose testing is that the labeled glucose must be fully metabolized in order to be measured as exhaled CO2. This means that (unlike blood glucose-based measurements) breath-based measurements reflect metabolic responses, including cellular metabolism. Studies are currently underway in our laboratory to evaluate potential applications of breath testing as a measure of whole-body insulin resistance, reflecting systemic as well as cellular insulin sensitivity.

Limitations

These studies were designed specifically to evaluate within-subject repeatability of these testing approaches. We are therefore unable to comment on several features of potential interest, including the impact of other variables such as age, gender, BMI, or preexisting dysglycemia on the performance of each of the tests in the various subgroups. Potential determinants of the observed variability, such as subtle differences in dietary intake, physical activity, and variable gastrointestinal absorption, were not assessed.

Conclusions

We have conducted a repeatability study of a noninvasive breath test-based approach to assessing glucose tolerance in a cohort of patients with wide range of glycemic control. We demonstrated superior repeatability of breath test-derived measurements of glucose handling compared to the standard 2-h blood glucose reading used in clinical practice. The breath test is a diagnostic tool that not only preserves the ability to measure the dynamic response to a glucose load at any given time point, but also simplifies the technique for both the patient and the provider.

Appendix

In a non-exercising subject, after a glucose load containing a small quantity of [13C6]glucose, breath CO2 is primarily derived from two carbon sources: fatty acids (from plasma and intra-myocellular sources) and 13C-labeled plasma glucose. Breath isotope enrichment is expressed as:

|

wherein R is the isotope ratio of 13CO2 and 12CO2. R° = 13C°/12C° is the isotope ratio measured prior to the 13C-OGTT drink.

Because 12C* is negligible compared with 12C°, the following expression results:

|

Because 13C* is proportional to the rate of whole-body Gox and 12C° is proportional to integrated glucose and Lox at baseline, the following assumptions can be made:

|

and

|

where k, k′, and k″ are constants.

Thus,

|

and

|

In practice, 1,000 × (R − R°) is denoted as ∂ with units as part per thousand (‰). Thus, rearranging the equation leads to:

|

(1) |

Equation 1 states that whole-body Lox/Gox is inversely proportional to the measured parameter (R–R°) and should move in the same direction as 2-h OGTT blood glucose during the progression of diabetes. Therefore, 1/∂ can be used as a noninvasive surrogate for the 2-h OGTT blood glucose with the potential for greater divergence from the normal value during the early stages of disease development.

We thus used the inverse of [AUC180 min time × 1,000] as a measure of ratio of Lox and Gox.

Acknowledgments

These studies were performed with the assistance and support of the Indiana University Clinical Translational Sciences Institute's Clinical Research Center (supported by grant UL1RR025761-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health). This work was performed under National Institutes of Health Small Business Technology Transfer support (grant 1R43DK079384, Principal Investigator M.J.) to BioChemAnalysis Corp., which is developing the breath test for potential future application. Study design, data collection, and data analyses were performed independently by the Indiana University investigators, who report no conflicts of interest regarding this work.

Author Disclosure Statement

P.S. and R.C. have no commercial associations or competing financial interests. M.J. is an employee of BioChem Analysis and is the Principal Investigator for the National Institutes of Health grant that supported this work. S.A.S. is an employee of BioChem Analysis. K.J.M. has received compensation for serving on the Merck speakers' bureau and declares no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1183–1197. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mooy JM. Grootenhuis PA. de Vries H. Kostense PJ. Popp-Snijders C. Bouter LM. Heine RJ. Intra-individual variation of glucose, specific insulin and proinsulin concentrations measured by two oral glucose tolerance tests in a general Caucasian population: the Hoorn Study. Diabetologia. 1996;39:298–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00418345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolever TM. Chiasson JL. Csima A. Hunt JA. Palmason C. Ross SA. Ryan EA. Variation of postprandial plasma glucose, palatability, and symptoms associated with a standardized mixed test meal versus 75 g oral glucose. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:336–340. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.3.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewanczuk RZ. Paty BW. Toth EL. Comparison of the [13C]glucose breath test to the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp when determining insulin resistance. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:441–447. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dillon EL. Janghorbani M. Angel JA. Casperson SL. Grady JJ. Urban RJ. Volpi E. Sheffield-Moore M. Novel noninvasive breath test method for screening individuals at risk for diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:430–435. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Felber JP. Ferrannini E. Golay A. Meyer HU. Theibaud D. Curchod B. Maeder E. Jequier E. DeFronzo RA. Role of lipid oxidation in pathogenesis of insulin resistance of obesity and type II diabetes. Diabetes. 1987;36:1341–1350. doi: 10.2337/diab.36.11.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz A. Nambi SS. Mather K. Baron AD. Follmann DA. Sullivan G. Quon MJ. Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:2402–2410. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.7.6661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jetha MM. Nzekwu U. Lewanczuk RZ. Ball GD. A novel, non-invasive 13C-glucose breath test to estimate insulin resistance in obese prepubertal children. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2009;22:1051–1059. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2009.22.11.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]