Abstract

Background

Finnish and Swedish waste water systems used by the forest industry were found to be exceptionally heavily contaminated with legionellae in 2005.

Case presentation

We report two cases of severe pneumonia in employees working at two separate mills in Finland in 2006. Legionella serological and urinary antigen tests were used to diagnose Legionnaires' disease in the symptomatic employees, who had worked at, or close to, waste water treatment plants. Since the findings indicated a Legionella infection, the waste water and home water systems were studied in more detail. The antibody response and Legionella urinary antigen finding of Case A indicated that the infection had been caused by Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. Case A had been exposed to legionellae while installing a pump into a post-clarification basin at the waste water treatment plant of mill A. Both the water and sludge in the basin contained high concentrations of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1, in addition to serogroups 3 and 13. Case B was working 200 meters downwind from a waste water treatment plant, which had an active sludge basin and cooling towers. The antibody response indicated that his disease was due to Legionella pneumophila serogroup 2. The cooling tower was the only site at the waste water treatment plant yielding that serogroup, though water in the active sludge basin yielded abundant growth of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 5 and Legionella rubrilucens. Both workers recovered from the disease.

Conclusion

These are the first reported cases of Legionnaires' disease in Finland associated with industrial waste water systems.

Background

From 1995 until 2007, the number of reported Legionnaires' disease (LD) cases in Finland has varied from 10 up to 31 per year, with an annual incidence of 2-6 cases per million [1]. The reporting of LD and Legionella-positive laboratory results has been mandatory for both clinicians and clinical laboratories since 1995. The incidence rate in Finland is much lower compared to the mean incidence rate of LD in European countries, which has been 11 cases per million in 2007 and 2008 [2].

Previous Finnish Legionella survey studies revealed that 30% of the hot water systems and 47% of the cooling water systems were contaminated with legionellae [3,4]. In addition, the few Finnish case studies where both clinical and environmental Legionella strains were obtained for molecular typing have indicated that hot water systems were the source of infection [5,6].

Following Swedish reports of extremely high concentrations of legionellae in biological waste water treatment plants and LD in an employee working near a plant [7], an environmental study was initiated focusing on waste water systems used by the Finnish paper and pulp industries. In the first part of the study, culturable legionellae were detected in 73% (11/15) of industrial active sludge basins containing waste water, with the highest concentration being 1.9 × 109 cfu/l (Unpublished data, Kusnetsov J, Torvinen E, Lehtola M and Miettinen IT). In addition, the microscopic PNA-FISH method [8] revealed Legionella pneumophila (L. pneumophila) cells to be present in all waste water basins (up to 1.7 × 1010 cells/l). After these environmental findings, two cases of LD were diagnosed via the occupational health services of the participating paper and pulp mills. These cases are reported here.

Case presentation

General awareness of potential Legionella exposure has increased recently in the paper and pulp industries. As a consequence, these two severe respiratory infections suffered by employees working in proximity of waste water treatment plants of two different paper and pulp mills were studied in more detail for suspected Legionella infection.

Methods

Legionella antigens were detected by urinary antigen immunochromatography (Binax-now, Inc. Portland). Serum antibodies against legionellae were first detected by an in-house EIA-method (TYKSLAB, Turku) and later with an in-house IFA-method (HUSLAB, Helsinki). The EIA-method detects antibodies against L. pneumophila serogroups 1 to 4 and L. micdadei [9] and the IFA-method detects IgG-, IgA-and IgM-antibodies against L. pneumophila serogroups 1 to 8 and L. gormanii, L. longbeachae, L. dumoffii, L. bozemanii and L. micdadei [10]. The definitions given by the European Working Group for Legionella Infections were followed to determine whether these cases were confirmed or presumptive LD cases [11].

At the workplaces, the water samples were analysed before and, in more detail, after these cases were diagnosed. For culture of waste waters, samples were diluted 3-fold before processing according to ISO 11731 [12]. Clean water samples were also diluted in the same way and also concentrated by filtration. Portions of diluted, undiluted and concentrated samples were inoculated directly, acid-washed (pH 2.2, 4 min) or heat-treated (50°C, 30 min) before inoculation onto GVPC medium plates (buffered charcoal yeast extract medium containing glycine, vancomycin, polymyxin B and cycloheximide, Oxoid Ltd, Cambridge, UK). Water samples from the hot and cold water systems of the cases' homes were analysed with the standard method [12], without dilution. Media plates were incubated for 10 days at 36 ± 1°C and colonies resembling legionellae were further confirmed by growth tests according to the standard method [12].

Serotyping of Legionella strains was first performed with the Oxoid Legionella Latex Test (DR0800 M, Oxoid). The L. pneumophila strains were further serogrouped with the Denka Seiken antisera set (Denka Seiken Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) or the Dresden panel of monoclonal antibodies (MAb) [13]. L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strains were further subgrouped using the Dresden monoclonal panel. Non-pneumophila Legionella strains were identified to species level by growth and biochemical tests and partial 16 S rRNA sequencing by commercial service at FIMM (FIMM, Helsinki, Finland) using primers fD1 Mod and 533r [14] and GenBank database [14].

In order to identify if Case B had been exposed via aerosols in the wind blowing from the direction of the waste water treatment plant, meteorological data for the period of his working hours were obtained from a local weather station situated 1200 meters from the waste water treatment plant.

Case A

Case A (male, 51 years, previously healthy, smoker) fell ill with pneumonia on August 9, 2006. Five days earlier, he had been accidentally exposed to aerosols of waste water, when water splashed during the installation of a new pump to the post-clarification basin. This basin separates water and sludge after the active sludge basin. The employees had been instructed to use respirators while working in the vicinity of the water treatment plant. Compliance with these instructions, however, was not good, and during the aerosol exposure, Case A had not been wearing a respirator.

Case A was diagnosed with legionellosis by urinary antigen immunoassay, this giving a positive response on the 7th day. The first serological tests displayed an antibody response to L. pneumophila (the 6th day, IgM++ and IgA+; the 23rd day, IgM+++, IgA+++, IgG+++) and L. micdadei (the 6th day, IgM+; the 23rd day IgM++, IgG+, in-house EIA). The last test was conducted ten weeks after the onset of illness with the in-house IFA, giving values of 1:256 for L. pneumophila serogroup 1 and 1:1024 for L. dumoffii, while other L. pneumophila serogroups and Legionella species had a titer 1:128 at their highest. Despite repeated cultures no clinical isolate was ever obtained. Medical treatment was started two days after the onset of symptoms and was initially based on cefuroxime, roxithromycin, meropenem, but subsequently on piperacillin, and moxifloxacin was administered after the diagnosis of LD had been established. The patient spent four days in intensive care, and he was discharged after two weeks in hospital. This radiography-confirmed pneumonia case was classified as a confirmed case of LD according to EWGLI case definitions.

Case B

Case B (male, 61 years, had stopped smoking five years previously) was diagnosed with pneumonia on September 24, 2006. He had been working about 200 m eastward from the active sludge basin and the cooling towers of the waste water treatment plant on days 4, 5, 6, 11, 12 and 13 before the onset of the respiratory symptoms. In the intervening days, he was not at work. This mill also instructed employees working in the vicinity of the water treatment plant to use respirators. However, Case B was not working at the waste water treatment plant and did not wear a respirator.

The diagnosis of LD for this radiography-confirmed case of pneumonia was based on serological tests. Nine days after the diagnosis, the patient tested seropositive for L. pneumophila serogroups 1-4 (IgM++, IgA+++, IgG+) and L. micdadei (IgG+, EIA). A subsequent serum sample analysed with IFA in another laboratory revealed a high titre for L. pneumophila serogroup 2 (1:4096, the 26th day) and it was still high even though declining (1:2048) 12 weeks after the onset of the illness. For L. micdadei, the titers were 1:256 and 1:256, and for other L. pneumophila serogroups and Legionella species the titer values were only up to 1:64 and 1:128 (the 26th day and 12 week samples). The difference between the causative serogroup and the other serogroups and species was at least two titer steps, showing the immune response specific for L. pneumophila serogroup 2.

His urinary antigen test was negative when tested on the 36th day. No culturing for legionellae from clinical samples was performed. He was treated with roxithromycin and he recovered at home. This pneumonia was classified as a presumptive LD case.

Neither of the two cases had travelled abroad during the incubation period.

Results of environmental study

In plant A, in February 2006, 2.0 × 107 cfu/l of L. pneumophila serogroup 13 was isolated from the active sludge basin, and 1.0 × 104 cfu/l of L. pneumophila serogroup 3 from water circulating around the plant (Table 1). After Case A had been diagnosed, the plant was sampled again, and high concentrations of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 were isolated from water in the active sludge basin, and from water and sludge in the post-clarification basin. Three strains of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 isolated from the post-clarification basin water and sludge were subtyped and the strains belonged to the monoclonal subgroup Bellingham.

Table 1.

Environmental findings from the workplace of Case A, plant A

| Date (before or after infection) |

Water systems sampled (sample type) |

Temperature (°C) |

Legionella concentration (cfu/l) |

Type of Legionella |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

28th Feb 2006 (before) |

Active sludge basin at the waste water treatment plant (water) |

33.0 | 2.0 × 107 | L. pneumophila serogroup 13 |

|

28th Feb 2006 (before) |

Circulating waste water at the waste water treatment plant (water) | 35.0 | 1.0 × 104 | L. pneumophila serogroup 3 |

|

29th Aug 2006 (after) |

Active sludge basin at the waste water treatment plant (water) |

36.0 | 1.0 × 106 | L. pneumophila serogroup 1 |

|

29th Aug 2006 (after) |

Post-clarification basin at the waste water treatment plant (water) | 35.0 | 2.3 × 104 | L. pneumophila serogroup 1, subgroup Bellingham |

|

29th Aug 2006 (after) |

Post-clarification basin at the waste water treatment plant (sludge) | 36.0 | 2.0 × 106 and 1.0 × 106 |

L. pneumophila serogroup 1, subgroup Bellingham and L. pneumophila serogroup 13 |

The domestic water systems of Case A were studied on August 29, 2006. Four samples were taken from the shower (mixture of hot and cold water, 35.5°C), kitchen tap (hot water, 55.0°C), toilet tap (mixture of hot and cold water, 35.5°C) and hose used outside the building (cold water, 10.2°C). All these domestic water samples were Legionella-negative.

In plant B, the active sludge basin was first sampled in August 2005, and 3.0 × 107 cfu/l of L. pneumophila serogroup 5 was detected (Table 2). After Case B had been diagnosed, new samples from the active sludge basin contained high concentrations of Legionella rubrilucens (8.0 × 109 cfu/l) and repeatedly L. pneumophila serogroup 5 (4.3 × 107 cfu/l). Legionellae were also isolated from a well where the rejected waste water was directed. In addition, a cooling tower at the water treatment plant, used for cooling of waste water, was sampled and yielded low concentration of L. pneumophila serogroup 2 (1.7 × 103 cfu/l). A few samples were also taken in November inside the mill, from paper machines and the shower used by Case B, but they did not contain culturable legionellae (Table 2).

Table 2.

Environmental findings from the workplace of Case B, plant B and mill B

| Date (before or after infection) |

Water systems sampled (sample type) |

Temperature (°C) |

Legionella concentration (cfu/l) |

Type of Legionella |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

16th Aug 2005 (before) |

Active sludge basin at the waste water treatment plant B (water) |

37.7 | 3.0 × 107 | L. pneumophila serogroup 5 |

|

15th Nov 2006 (after) |

Active sludge basin at the waste water treatment plant B (water) |

35.2 | 4.3 × 107 and 8.0 × 109 |

L. pneumophila serogroup 5 and L. rubrilucens |

|

15th Nov 2006 (after) |

Cooling tower at the waste water treatment plant B (water) | 37.3 | 1.7 × 103 | L. pneumophila serogroup 2 |

|

15th Nov 2006 (after) |

Well of rejected waste water at plant B (water) | 31.0 | 3.2 × 107 and 2.0 × 108 |

L. pneumophila serogroup 5 and L. rubrilucens |

|

15th Nov 2006 (after) |

Process water, paper machine X, mill B (water) | 50.0 | Not detected | |

|

15th Nov 2006 (after) |

Process water, paper machines X and Y, mill B (water) | 35.1 | Not detected | |

|

15th Nov 2006 (after) |

Shower water system in mill B, used by Case B (water) | 35.0 | Not detected | |

The domestic water systems of Case B were studied on November 23, 2006. The samples taken from the shower (mixture of hot and cold water, 37.7°C), kitchen tap (hot water, 53.4°C) and toilet tap (cold water, 11.3°C) were Legionella-negative.

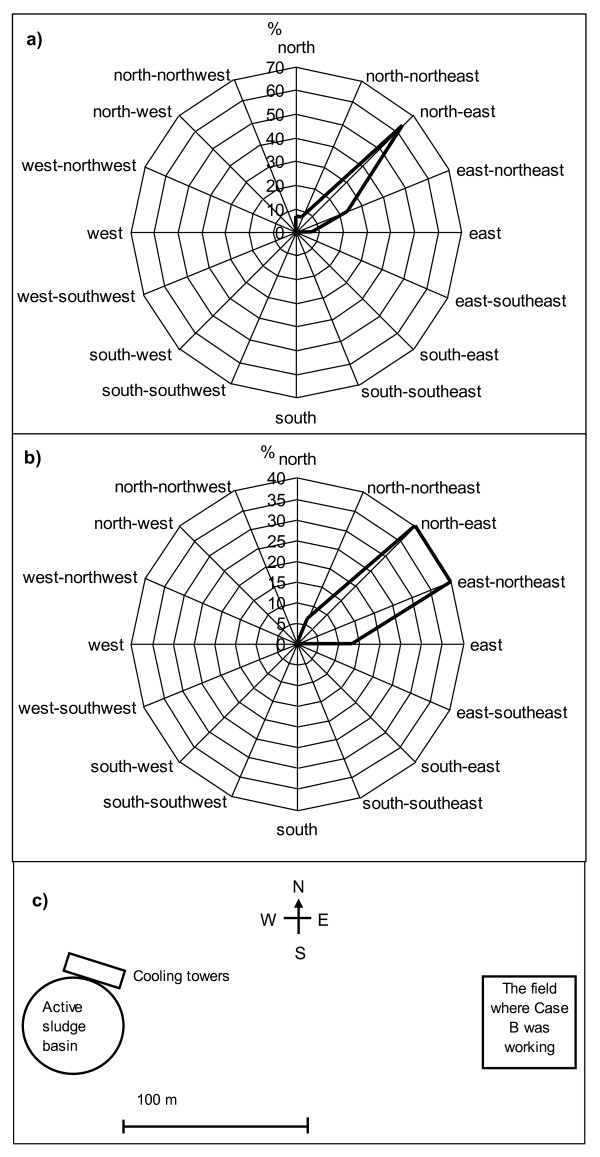

Meteorological data reported that the wind had blown from south-west, west-southwest, south, south-south-west and west during the period of the latest working days and hours of Case B before the onset of symptoms. The wind speed was only from 1.1 to 4.2. m/s. This data from the local weather station, which was situated close to the waste water treatment plant B, was used to draw the inverse wind roses in Figure 1. Case B had been working in a field situated east from the waste water treatment plant B, and was exposed to the wind blowing exactly from west to east for at least four hours, 13 days before the onset of his symptoms.

Figure 1.

Inverse wind roses (a, b) showing the direction where the wind had blown to, and location of the field where the Case B had been working, in relation to active sludge basin and cooling towers of the plant B (c). The wind data from the last working periods are drawn in separate inverse wind roses, a) is the wind data on days 4, 5 and 6 and b) on days 11, 12 and 13 days before the onset of symptoms in Case B.

Discussion and Conclusion

This is the first report of LD cases associated with industrial waste water systems in Finland. In Case A, the positive urinary antigen test, and the antibody respose indicated that the infection was caused by L. pneumophila serogroup 1. The exposure to aerosols generated from waste water of the post-clarification basin was apparent and because L. pneumophila serogroup 1 was detected only in waste water samples, the most likely source of this Legionella infection was the post-clarification basin.

The antibody response of Case B suggested that LD was caused by L. pneumophila serogroup 2. This serogroup was isolated only from the cooling tower at the waste water treatment plant. In September 2006, the cooling towers were used occasionally, which was usual at that time of the year, meaning that a direct route via the cooling towers was possible. Water from the cooling towers flowed into the active sludge basin. Thus L. pneumophila serogroup 2 was very likely to be present in the active sludge basin, at least in low concentrations. However, it was not possible to detect by culture among the abundant growth of other Legionella strains and other microbes.

In 2007 and 2008, a total of 11897 LD cases were detected in Europe [2]. Most of these cases were diagnosed with UA test (81%) and only a few of the cases with the isolation of legionellae (8.8%). Thus it is very common that Legionella infections are diagnosed without Legionella isolates, which are needed for confirming the source. We were also unable to obtain clinical isolates in this study but were able to exclude some of the sources and focus on the most likely sources of transmission.

As Case B was working in a field about 200 m east of the active sludge basin and the cooling towers, meteorological data indicated that he was likely to have been exposed to aerosols originating from the waste water treatment plant. The incubation period of LD is generally between two and ten days. However, in the Dutch Flower Show outbreak in 1999, 16% of cases occurred after 10 days, up to 19 days [15]. In addition, in the 1976 Philadelphia outbreak incubation periods as long as 26 days were reported [16]. In Case A, the incubation time was five days. In Case B, the exact incubation period remained uncertain, as he had been working during the previous two weeks (days 4, 5, 6, 11, 12, 13) before the onset of symptoms under similar conditions. However, particularly on day 13, before the onset of symptoms, the wind was blowing for four hours from the waste water treatment plant exactly in the direction in which he was working. It is therefore possible that the incubation period exceeded 10 days, being up to 13 days in his case. After the domestic water systems and other water systems in the mill were excluded as possible sources, the waste water treatment plant remained the most likely source of the Legionella infection in Case B.

It is notable that even though very high concentrations of L. rubrilucens and L. pneumophila serogroup 5 were found in the waste water system of plant B, the antibody response indicated that he was suffering a L. pneumophila serogroup 2 infection; this serogroup was detected in much smaller concentrations at the plant. According to EWGLI data of LD cases from 1995 to 2006, 0.8% (33/4390) of the clinical Legionella isolates were L. pneumophila serogroup 2 [personal communication, Carol Joseph, 2009, EWGLI data, Health Protection Agency, London, England]. Equally rare were isolations of serogroup 5 of L. pneumophila (1.0%), in comparison to the isolations of serogroup 1 (73.8%), serogroup 3 (3.8%) and serogroup 6 (2.2%). In addition, L. rubrilucens has been known to be a cause of LD only once [17], showing that the species probably is much less virulent than all serogroups of L. pneumophila. The antibody response to L. pneumophila serogroup 2 does not rule out the possibility that the infection could have been caused by other legionellae, especially by those L. pneumophila serogroups prevailing in the waste water plant. Previously, L. pneumophila serogroup 5 has been associated with an outbreak of nosocomial legionellosis in Finland [6].

The dose of Legionella cells causing LD is not known precisely, nor how long one has to breath air with aerosols contaminated by legionellae before becoming infected. In the large outbreak in Pas-de-Calais, spending over 100 minutes outdoors daily increased the risk of LD significantly [18]. Prior to the onset of symptoms, Case B worked for at least 240 minutes (on day 13) downwind of the waste water treatment plant.

The laboratory results and environmental evidence of these two cases indicated that the LD infections were acquired at work, at or very close to the waste water treatment plants. No other previous or simultaneous Legionella infections have been known to occur among employees working at plants A or B, even though equally high Legionella concentrations most probably have existed in these waste water systems for years. The employees have worn respirators as protection against legionellae since 2005, and this may have prevented infections. Another explanation for the low number of cases could be underdiagnosis, since industrial waste water systems have been associated with abundant Legionella growth only since the Pas-de-Calais outbreak in 2003-2004 [18]. Therefore these waste water systems have not been investigated as possible sources of Legionella infections. Furthermore, the monoclonal subtype Bellingham of L. pneumophila serogroup 1 found in the plant A, does not belong to MAb 3/1 subgroup, which is the most virulent subtype of serogroup 1 [19], and L. pneumophila serogroups 2 and 5 rarely cause LD.

The two cases reported here have similarities to the previous Swedish case, where an employee of a paper and pulp mill most likely acquired infection while working 100 meters from a waste water treatment plant [7]. In that case, the clinical Legionella strain (L. pneumphila serogroup 1 subtype Benidorm, MAb 3/1 positive) and the environmental strain from the waste water basin were identical by molecular typing. In addition, an outbreak of five cases of Pontiac fever occurred after exposure to aerosols from sludge in a sewage treatment plant of the Danish food industry [20]. The strain isolated from sludge in concentrations of 1.5 × 107 cfu/g was L. pneumophila serogroup 1, subgroup OLDA/Oxford (MAb 3/1 negative). In this outbreak, the workers used respirators, but the filters were effective only against chemical substances.

Previously, a large community outbreak with 86 cases of LD was associated with cooling towers and waste water basins of a petrochemical plant occurred in France in 2003-2004 [18]. The strain causing the outbreak was L. pneumophila serogroup 1, strain Lens. The aerosols with legionellae, spread by a cooling tower, were infectious at a distance of at least six kilometers. The plant was later closed. In Norway, an air-scrubber was spreading Legionella aerosols over a distance of ten kilometers, resulting in 103 LD cases and ten deaths [21,22]. It is assumed that aerosols containing Legionella from the waste water aeration ponds originally contaminated the air scrubber. The scrubber was cleaned of legionellae and the aeration pond changed to an anaerobe pond. Thus, the sources of these larger outbreaks have been limited.

In contrast, Swedish and Finnish studies have indicated that heavy contamination of active sludge basins with legionellae is very common [7], (Unpublished data, Kusnetsov J, Torvinen E, Lehtola M and Miettinen IT). Further, air samplings in Norway and France in the vicinity of active sludge basins revealed that viable Legionella cells can be isolated up to 180-270 meters downwind [23,24]. It seems therefore likely that any waste water treatment plant with an active sludge basin under aeration can contain higher concentrations of Legionella bacteria and also produce aerosols with legionellae. Evidence of exposure to legionellae can be established if an increased frequency of elevated Legionella antibodies in serum samples can be detected [22].

In addition, some of these waste water treatment plants use cooling towers to lower the waste water temperature. It would be very useful to know if these waste water cooling towers are clean and maintained in accordance with the European and WHO Legionella guidelines [11,25]. In the European guidelines, a concentration of 1000 cfu/l of legionellae is recommended as the highest acceptable concentration which can be present in cooling water (technical guidelines).

Water treatment plants with active sludge basins should be considered as a possible source of community acquired Legionella infections, directly or indirectly via cooling towers. In addition, the employees should protect themselves by using respirators at or in the vicinity of water treatment plants. The Finnish Work safety act (738/2002) [26] has stated that employees should be protected against biological factors, including Legionella bacteria, at waste water treatment plants. Especially in industrial waste water treatment plants with high water temperatures, Legionella concentrations may be very high. In 2005, Finnish forest industry employees were instructed to use respirators while working in the vicinity of the water treatment plants. Developing ways to lower Legionella concentrations in these water systems would be the next step in diminishing the risk of Legionella infection.

These LD cases might have remained undiagnosed if our environmental study had not increased awareness about potential Legionella exposure in waste water treatment plants. These findings suggest that the clinicians should consider LD when treating patients with pneumonia from these industrial settings.

Consent

Written informed consents were obtained from the Cases for publication of this report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JK arranged environmental samplings, interviewed the patients, wrote the first version of the manuscript, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. L-KN and TK were the physicians who cared for the cases, SAU and SM did typing of Legionella strains, and TP, TMNN and K-PM collected data. All the authors revised the article and approved the final version.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Jaana Kusnetsov, Email: jaana.kusnetsov@thl.fi.

Liisa-Kaarina Neuvonen, Email: liisa-kaarina.neuvonen@condia.fi.

Timo Korpio, Email: timo.korpio@upm-kymmene.com.

Søren A Uldum, Email: SU@ssi.dk.

Silja Mentula, Email: silja.mentula@thl.fi.

Tuula Putus, Email: tuula.putus@utu.fi.

Nhu Nguyen Tran Minh, Email: TranMinhN@wpro.who.int.

Kari-Pekka Martimo, Email: kari-pekka.martimo@mehilainen.fi.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the case employees for their co-operation and for providing consent for publication of this report. The awareness of occupational health nurse Ms. Anneli Junes is gratefully acknowledged. Health inspectors involved in this study are warmly acknowledged. We also wish to thank Ms. Riitta Lahtinen for providing expert help with the environmental study. The skillful laboratory assistance of Ms. Marjo Tiittanen is gratefully acknowledged. We warmly thank Dr. Ewen Macdonald and Dr. Diane Lindsay for their support with English language. A part of this study was funded by Finnish Work Environment Fund (FEEL-study, number 105304).

References

- Ruotsalainen E, Lyytikäinen O. In: Tartuntataudit Suomessa 2007. Hulkko T, Lyytikäinen O, Kuusi M, Iivonen J, Ruutu P, editor. Helsinki: Publications of the National Public Health Institute (KTL); 2008. Legionella. B10:9. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph CA, Ricketts KD. on behalf of the European Working Group for Legionella Infections. Legionnaires' disease in Europe 2007-2008. In Euro Surveill. 2010;15(Issue 8) doi: 10.2807/esm.09.10.00480-en. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacheus O, Martikainen PJ. Occurrence of legionellae in hot water distribution systems of Finnish apartment buildings. Can J Microbiol. 1994;40(12):993–999. doi: 10.1139/m94-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnetsov JM, Martikainen PJ, Jousimies-Somer HR, Väisänen M-L, Tulkki AI, Ahonen HE, Nevalainen AI. Physical, chemical and microbiological water characteristics associated with the occurrence of Legionella in cooling tower systems. Wat Res. 1993;27(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(93)90198-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skogberg K, Nuorti PJ, Saxen H, Kusnetsov J, Mentula S, Fellman V, Mäki-Petäys N, Jousimies-Somer H. A newborn with domestically acquired Legionnaires' disease confirmed by molecular typing. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(8):e82–e85. doi: 10.1086/342886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perola O, Kauppinen J, Kusnetsov J, Kärkkäinen U-M, Lück PC, Katila M-L. Persistent Legionella pneumophila colonization of a hospital water supply: efficacy of control methods and a molecular epidemiological analysis. APMIS. 2005;113(1):45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm1130107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allestam G, de Jong B, Långmark J. In: Legionella State of Art 30 Years after Its Recognition. Cianciotto NP, Abu Kwaik Y, Edelstein PH, Fields BS, Geary DF, Harrison TG, Joseph CA, Ratcliff RM, Stout JE, Swanson MS, editor. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2006. Biological treatment of industrial wastewater: a possible source of Legionella infection; pp. 493–496. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks S, Keevil CW. Targeting species-specific low-affinity 16 S rRNA binding sites by using peptide nucleic acids for detection of legionellae in biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(8):5453–5462. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02918-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. In: Manual of molecular and clinical laboratory immunology. 7. Detrick B, Hamilton RG, Folds JD, editor. Washington (DC): ASM Press; 2006. Detection of antibodies to Legionella; pp. 468–476. [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein P. In: Manual of clinical laboratory immunology. 4. Rose NR, de Macario EC, Fahey JL, Friedman H, Penn GM, editor. Washington (DC): American Society for Microbiology; 1992. Detection of antibodies to Legionella; pp. 459–466. [Google Scholar]

- European Working Group for Legionella Infections (EWGLI) The European guidelines for control and prevention of travel associated Legionnaires' disease. 2005.

- International standard ISO 11731. Water quality-Detection and enumeration of Legionella. ISO 11731:1998 (E) --- Either ISSN or Journal title must be supplied.

- Helbig JH, Kurtz JB, Castellani-Pastoris M, Pelaz C, Lück PC. Antigenic lipopolysaccharide components of Legionella pneumophila recognized by monoclonal antibodies: possibilities and limitations for division into serogroups. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(11):2841–2845. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.11.2841-2845.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DJ, Pace B, Olsen GJ, Stahl DA, Sogin ML, Pace NR. Rapid determination of 16 S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;82(20):6955–6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Den Boer JW, Yzerman EPF, Schellekens J, Lettinga KD, Boshuizen HC, Van Steenbergen JE, Bosman A, Van den Hof S, Van Vliet HA, Peeters MF, Van Ketel RJ, Speelman P, Kool JL, Conyn-Van Spaendonck MA. A large outbreak of Legionnaires' Disease at a Flower Show, the Netherlands, 1999. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(1):37–43. doi: 10.3201/eid0801.010176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser DW, Tsai TR, Orenstein W, Parkin WE, Beecham HJ, Sharrar RG, Harris J, Mallison GF, Martin SM, McDade JE, Shepard CC, Brachman PD. the field investigation team. Legionnaires' disease, description of an epidemic of pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1977;297(22):1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197712012972201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger P, Papazian L, Drancourt M, La Scola B, Auffray JP, Raoult D. Ameba-associated microorganisms and diagnosis of nosocomial pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(2):248–255. doi: 10.3201/eid1202.050434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Minh NN, Ilef D, Jarraud S, Rouil L, Campese C, Che D, Haeghebaert S, Ganiayre F, Marcel F, Etienne J, Desenclos JC. A community outbreak of Legionnaires' disease linked to industrial cooling towers-how far can airborne transmission spread. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(1):102–111. doi: 10.1086/498575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig JH, Bernander S, Castellani Pastoris M, Etienne J, Gaia V, Lauwers S, Lindsay D, Lück PC, Marques T, Mentula S, Peeters MF, Pelaz C, Struelens M, Uldum SA, Wewalka G, Harrison TG. Pan-European study on culture-proven Legionnaires' Disease: distribution of Legionella pneumophila serogroups and monoclonal subgroups. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;21(10):710–716. doi: 10.1007/s10096-002-0820-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregersen P, Grunnet K, Uldum S, Andersen B, Madsen H. Pontiac fever at a sewage treatment plant in the food industry. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1999;25(3):291–295. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygård K, Werner-Johansen O, Ronsen S, Caugant DA, Simonsen O, Kanestrøm A, Ask E, Ringstad J, Ødegård R, Jensen T, Krogh T, Høiby EA, Ragnhildstveit E, Aaberge IS, Aavitsland P. An outbreak of Legionnaires disease caused by long-distance spread from an industrial air scrubber in Sarpsborg, Norway. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(1):61–69. doi: 10.1086/524016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedege E, Bergdal T, Bolstad K, Caugant DA, Efskind J, Heier HE, Kanestrøm A, Strand BH, Aaberge IS. Seroepidemiological study after a long-distance industrial outbreak of Legionnaires' Disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16(4):528–534. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00458-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatny JM, Reif BAP, Skogan G, Andreassen O, Høiby EA, Ask E, Waagen V, Aanonsen D, Aaberge IS, Caugant DA. Tracking airborne Legionella and Legionella pneumophila at the biological treatment plant. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42(19):7360–7367. doi: 10.1021/es800306m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu L, Robine E, Deloge-Abarkan M, Ritoux R, Pauly D, Hartemann P, Zmirou-Navier D. Legionella bacteria in aerosols: Sampling and analytical approaches used during the Legionnaires' disease outbreak in Pas-de-Calais. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(9):1333–1335. doi: 10.1086/503115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Legionella and the prevention of legionellosis. 2007. http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/emerging/legionella/en/index.html --- Either ISSN or Journal title must be supplied.

- Finnish legislation. Work safety Act, Työturvallisuuslaki 738/2002. http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2002/20020738 --- Either ISSN or Journal title must be supplied.