Abstract

Objective

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by autoantibody production and immune complex deposition. Interleukin-10 (IL-10), predominantly an anti-inflammatory cytokine, is paradoxically elevated in SLE patients. We hypothesize that the anti-inflammatory function of IL-10 is impaired in monocytes from SLE patients who are chronically exposed to immune complexes.

Methods

CD14+ monocytes were isolated from healthy donors and SLE patients with all experiments done in pairs. Cultured CD14+ cells were treated with heat-aggregated human IgG (HIg 325 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of IL-10 (20 ng/ml). To study gene expression, RNA was extracted 3 hours after treatment. To study cytokine production, supernatants were harvested after 8 hours. To study IL-10 signaling, cell lysates were obtained from CD14+ cells treated with HIg (325 μg/ml) for 1 hour followed by IL-10 (20 ng/ml) treatment for 10 minutes. Western blot was used to assess STAT3 phosphorylation.

Results

SLE monocytes produced more TNFα and IL-6 than control cells when stimulated with HIg. IL-10 had less suppressive effect on HIg-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in SLE monocytes, although IL-10 receptor expression was similar in SLE and control monocytes. HIg suppressed IL-10R expression and altered IL-10 signaling in control monocytes. Like SLE monocytes, IFNα-primed control monocytes stimulated with HIg were also less responsive to IL-10.

Conclusion

HIg and IFNα modulate IL-10 function. In SLE monocytes, which are considered IFNα-primed and chronically exposed to immune complexes, responses to IL-10 are abnormal, limiting the anti-inflammatory effect of this cytokine.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by autoantibody production and immune complex tissue deposition. The clinical picture of lupus varies from mild skin lesions to severe organ damage, such as glomerulonephritis that may ultimately result in end stage renal disease. Inflammatory illnesses such as lupus are characterized by an aberrant cytokine profile; the balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is tipped towards inflammation. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) plays a key role in maintaining this balance, as it blocks inflammatory cytokine synthesis (1), chemokine secretion (2), inflammatory enzyme production and expression of co-stimulatory molecules including CD80, CD86 and MHC Class II (3). To limit inflammation, IL-10 also promotes production of IL-1 receptor antagonists and soluble TNFα receptors (1). In certain cases, however, IL-10 exerts immunostimulatory effects, acting as a potent cofactor for proliferation, differentiation, class switching, and antibody production in B lymphocytes (1).

IL-10 is among the cytokines thought to be dysregulated in SLE. Serum IL-10 levels are elevated in SLE patients and the extent of elevation correlates with disease activity (4). Polymorphisms within the IL-10 gene promoter that are associated with high IL-10 levels may be important in the development of certain clinical features in SLE (5,6). Monocytes and B lymphocytes from SLE patients spontaneously produce high amounts of IL-10 in vitro (7,8) Cells from healthy relatives of SLE patients also produce increased amounts of IL-10 (9), suggesting that IL-10 may be a pathogenic factor in lupus. Indeed, immunoglobulin production by B lymphocytes in SLE is in part IL-10 dependent (10), and, in one small human trial, anti-IL-10 monoclonal antibody therapy was shown to be beneficial for SLE patients with active, steroid-dependent disease (11).

SLE is characterized by increased production and decreased clearance of immune complexes. In SLE, immune complexes mediate tissue damage by cross-linking myeloid cell surface Fcγ recptors (FcγRs), thereby activating cellular effector functions, including phagocytosis of pathogens, endocytosis of immune complexes, and production of cytokines, chemokines and reactive oxygen intermediates (12–15). In the presence of IgG-containing immune complexes, macrophages produce high levels of IL-10, which can dampen innate inflammatory responses to microbial infections (16), or, in lupus patients, affect the autoimmune response. Previous studies have shown that IL-10 activity is suppressed at the level of Jak-Stat signal transduction when FcγRs are crosslinked by immune complexes in IFNγ-primed macrophages (17).

Given paradoxically high levels of IL-10 and the abundance of immune complexes in SLE patients, we hypothesize that the anti-inflammatory function of IL-10 is limited in SLE monocytes, leading to unrestrained monocyte activation at sites of immune complex deposition.

METHODS

Patients and healthy controls

Peripheral blood was obtained from 17 disease-free volunteers and 17 patients who fulfilled ACR criteria for SLE. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, acute infection, renal failure (serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL) and daily steroid dose greater than prednisone 30 mg or its equivalent. All patients gave informed consent for this study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hospital for Special Surgery.

Reagents and cell culture

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from whole blood from healthy donors and SLE patients by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Monocytes, purified by magnetic beads (Stem Cell Technologies, Inc., Vancouver, Canada), were greater than 97% CD14 positive and were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, California, USA) for 12 hours before treatment with various reagents. There were 1×106 monocytes in each culture well. In some experiments, monocytes were cultured with recombinant human IL-10, recombinant human macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), recombinant human interferon-α (IFNα) (Biosource International, Camarillo, California, USA), heat-aggregated human IgG (HIg) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma Chemical Company).

Preparation of heat-aggregated IgG

Human IgG was purified from healthy donor plasma using affinity chromatography with protein G-sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) and concentrated to 20 mg/ml in sterile, cell culture grade phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Invitrogen Corp, Carlsbad, CA) using Centriprep ultracentrifugation devices (Millipore, MA, USA). Endotoxin was depleted using Detoxi-Gel endotoxin removing gel (Pierce Chemical Co., Rochford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Using the Limulus Amebocyte assay, both neat samples and serial dilutions of purified IgG tested at less than 0.03 EU/ml. To prepare heat-aggregated IgG (HIg), purified human IgG was heated at 63°C for 30 minutes. The HIg contained soluble (>75%) and insoluble complexes, all of which were used for monocyte treatment.

Cytokine production

Human tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), human interleukin-6 (IL-6) (R&D Systems Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA) and human IL-10 (BD Biosciences Pharmingen, San Diego, California, USA) in culture supernatants were measured by ELISA according to manufacturer's recommendation. Suppression of cytokine production by IL-10 is calculated with the following formula [cytokine production induced by HIg-(HIg+IL-10)]/HIg×100%.

Cytokine gene expression

To measure IL-6 gene expression, monocyte RNA was obtained by using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed using SuperScript II RNase H Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA). Real time quantitative PCR was performed by using the iCycler iQ thermal cycler and detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA). mRNA was normalized relative to GAPDH mRNA.

IL-10 signaling

Protein lysates from monocytes (25μg) were fractionated by electrophoresis with a 10% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was probed with monoclonal antibodies against phosphorylated STAT3 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Beverly, Massachusetts, USA) or total STAT3 (BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Kentucky, USA) and visualized with ECL plus Western blotting detection system (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA). Bands were quantified by multiplying mean intensity with the area. Within each paired experiment of control and SLE monocytes, phospho-STAT3 band quantity was adjusted relative to total STAT3 levels. Percentage reduction of phospho-STAT3 was calculated with the following formula: (total STAT3-phosphoSTAT3)/total STAT3 × 100%.

IL-10R expression

Monocytes were incubated for 30 min at 4°c with 10 μl of monoclonal anti-CD210 (IL-10Rα) (BD Pharmingen). Flow cytometry analysis was performed using BD Facscan. Flow cytometry data were collected in list mode and analyzed using CellQuest software (BD Immunocytometry Systems). Area under the curve (AUC) is defined as percentage of positively stained cells multiplied by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

Statistical analysis

Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare was used to compare differences in results of experiments with SLE and control monocytes. Data are expressed as means ± SD. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

SLE monocytes stimulated with HIg produced more TNFα and IL-6 but similar amounts of IL-10 relative to control monocytes

Given that immune complexes are potent triggers of pro-inflammatory cytokines in monocytes (13,14) and that SLE is characterized by aberrant cytokine profiles, we sought to determine whether SLE monocytes produce more pro-inflammatory cytokines in response to model immune complexes (HIg). We compared HIg-induced TNFα and IL-6 production from monocytes purified from healthy donors and SLE patients. In a series of paired experiments, control and SLE monocytes were simultaneously treated with HIg and cytokine production measured by ELISA. Compared with controls, SLE monocytes produced significantly more TNFα (p=0.03) and IL-6 (p=0.002) (Fig. 1a and 1b).

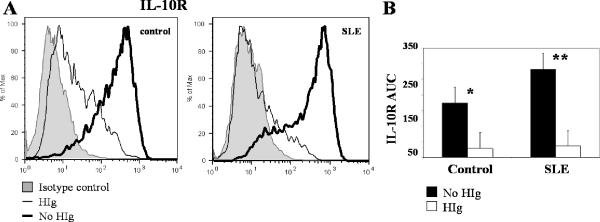

Figure 1. HIg-induced cytokine production and effect of IL-10.

CD14+ monocytes were purified from healthy donor and SLE patient blood. All experiments were done in pairs. Control and SLE monocytes were treated with HIg (325 μg/ml), in the presence or absence of interleukin-10 (IL-10) (20 ng/ml). All 17 experiments were done in pairs. Culture supernatants were harvested after 8 hours of incubation. Suppression rate of cytokine production by adding exogenous IL-10 was compared between control and SLE. A, TNFα production was measured by ELISA. B, IL-6 production was measured by ELISA. C, IL-10 production was measured by ELISA. D, Control and SLE monocytes were treated with HIg (325 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of IL-10 (20 ng/ml). RNA lysates were extracted after 3 hours of incubation. IL-6 mRNA was measured using RT-PCR, with results normalized to the values for GAPDH. Suppression of IL-6 gene expression by IL-10 was compared between control and SLE. * p=0.01 and ** p=0.002

Cross-linking monocyte FcγRs leads to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as anti-inflammatory cytokines (13,14), and the latter provides a means to limit amplification of cell activation and tissue injury. We considered the possibility that decreased HIg-stimulated production of IL-10 contributes to the excessive TNFα and IL-6 production in SLE monocytes. Measurement of IL-10 produced in response to stimulation with HIg showed this was not the case. Control and SLE monocytes stimulated with HIg released similar amounts of IL-10 (p=0.1) (Fig. 1c). Our results show that SLE monocytes produced more pro-inflammatory cytolines (TNFα and IL-6) despite producing similar amounts of anti-inflammatory IL-10.

IL-10 had less suppressive effects on HIg-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in SLE monocytes

The finding that IL-10 production in SLE monocytes was similar to controls while TNFα and IL-6 levels were higher suggested that monocytes from SLE patients might be less responsive to the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10. Indeed, the capacity of additional exogenous IL-10 to suppress HIg-induced TNFα production was decreased in SLE monocytes compared with simultaneously studied controls (% suppression: control, 73 ± 7 %; SLE 66 ± 11 %, n=17, p= 0.01) (Fig. 1a). Of note, absolute levels of TNFα were markedly higher in SLE, in the presence (p=0.002) and absence of IL-10 (p=0.03).

Suppression of HIg-induced IL-6 production by exogenous IL-10 was also decreased in SLE monocytes (% suppression: control 74% ± 12%; SLE 62% ± 14%, n=17, p=0.01) (Fig. 1b). Examination of IL-6 mRNA levels by real time quantitative PCR confirmed that IL-10 is less suppressive in SLE monocytes treated with HIg as compared to paired controls (p=0.002) (Fig. 1d). Absolute levels of IL-6 were higher in SLE in the presence (p=0.007) or absence of IL-10 (p=0.002). These observations show that IL-10 is less effective in suppressing HIg-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in SLE monocytes.

Immune complexes decreased IL-10R expression and IL-10 signaling in control and SLE monocytes

IL-10 has been shown to profoundly inhibit LPS-stimulated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (1). We observed only partial inhibition of immune complex-induced TNFα and IL-6 release in control monocytes (73% ± 7 % and 74% ± 12%, respectively). To explore the basis for this difference, we compared the capacity of IL-10 to suppress LPS and HIg responses. In our system, IL-10 completely suppressed TNFα production in LPS-stimulated control monocytes (LPS: 3.01 ± 1.86 ng/ml, LPS+IL-10: 0.05 ± 0.06 ng/ml, n=8, p=0.008). In contrast, IL-10 had less of a suppressive effect on HIg-induced TNFα production, suggesting that immune complex stimulation via Fc□Rs attenuates the suppressive effects of IL-10.

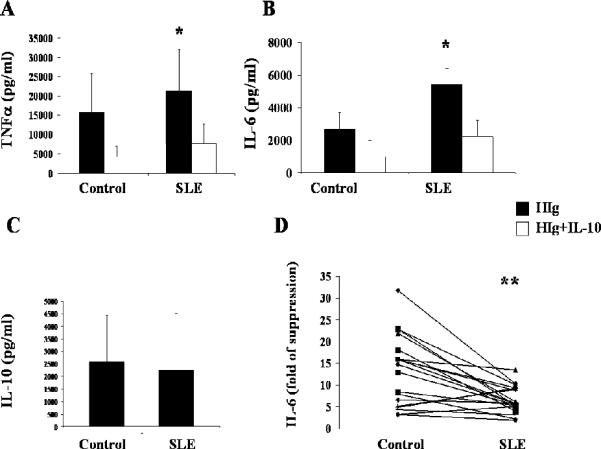

To explore the mechanism by which HIg attenuates the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10, we examined the effects of FcγR ligation on IL-10R expression. In control monocytes, IL-10R was downregulated by treatment with HIg (p=0.0006). The presence of immune complexes decreased IL-10R in SLE monocytes to a similar extent as in controls (p=0.003) (Fig. 2). Because SLE is characterized by increased levels of immune complexes and immune complexes downregulate IL-10R, we predicted that baseline levels of IL-10R would be lower in SLE monocytes. In an expanded series of patients, we observed similar levels of IL-10R in SLE and control monocytes (n=6 pairs, p=0.2), a finding consistent with previous reports (18).

Figure 2. IL-10R expression in control and SLE monocytes treated with HIg.

A, One representative flow cytometry histogram shown. Monocytes were treated with or without HIg (325 μg/ml) for 3 hours before IL-10 receptor (IL-10R) was measured by flow cytometry. B, Results of three paired experiments. Area under the curve (AUC), defined as percentage of positively stained cells multiplied by mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was compared between HIg and no HIg group. * p=0.0006 and ** p=0.003

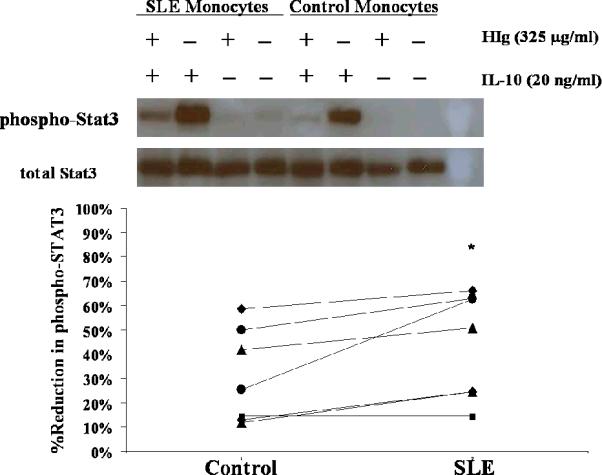

Because altered IL-10R expression could not explain the difference in responses between SLE and control monocytes, we examined IL-10 signaling. Stimulating monocytes with IL-10 leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3, that mediates the downstream anti-inflammatory effect of IL-10. Given that HIg decreased IL-10R expression, we expected to see decreased IL-10 signaling in the presence of HIg, as assessed by phospho-STAT3 levels. We compared phospho-STAT3 levels in monocytes treated with HIg and IL-10 to those in cells treated with IL-10 alone. In both control and SLE monocytes treated with HIg, IL-10 signaling was inhibited (Fig. 3). The decrease in IL-10 induced phospho-STAT3 in SLE monocytes stimulated with HIg was significantly greater than that in controls (p=0.02). Because SLE monocytes are constantly exposed to immune complexes in vivo, yet have no decrease in IL-10R (18) (Fig. 2), we considered the possibility that IL-10 signaling was altered in SLE. Comparison of IL-10 induced phosphorylation of STAT3 in SLE monocytes to controls did not reveal significant differences (phospho-STAT3 ratio of SLE:control: 1± 0.4, p=0.8). Taken together, these observations suggest that in the presence of immune complexes, both SLE and control monocytes had down-regulated IL-10R and blunted IL-10 signaling, but inhibition of IL-10 signaling was greater in SLE monocytes.

Figure 3. IL-10 signaling in monocytes treated with HIg.

Paired control and SLE monocytes were treated with or without HIg (325 μg/ml) for one hour before IL-10 (20 ng/ml) was added. Cells were harvested 10 minutes after IL-10 treatment and protein lysates extracted. Phosphorylated and total STAT3 levels were examined by Western Blot. Upper panel, One representative experiment of seven. Lower panel, Bands were quantified by multiplying mean intensity and the area. Percentage reduction of phosphorylated STAT-3 in the presence of HIg was compared between control and SLE. * p=0.02

Interferon-α decreased monocyte response to IL-10

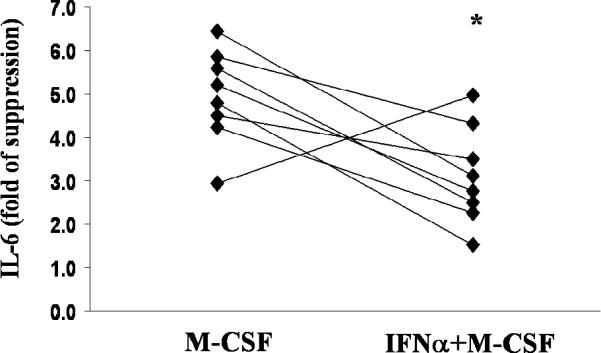

Because the impaired capacity of IL-10 to decrease inflammatory cytokine production in SLE monocytes cannot be explained by immune complex-induced changes in IL-10R expression or STAT3 signaling, we considered an alternative explanation for our observations. Peripheral blood cells from SLE patients show increased expression of IFNα inducible genes and their plasma has elevated levels of Type I Interferons (19). We tested the hypothesis that elevated IFNα in SLE influences IL-10 function. SLE cytokine milieu was simulated in vitro by priming control monocytes with IFNα plus M-CSF or M-CSF alone for 16 hours before treatment with HIg and/or IL-10. We examined the effects of treatment with IFNα on the capacity of IL-10 to block IL-6 gene expression induced by immune complexes. As shown in Figure 5, IL-10 was less effective in suppressing HIg-induced IL-6 gene expression in IFNα-primed cells compared to cells that were exposed to M-CSF only (p=0.05). These results show that exposure to IFNα attenuates the anti-inflammatory responses to IL-10 and provide a mechanism to explain the failure of IL-10 to effectively down-regulate immune complex-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production in SLE.

DISCUSSION

IL-10 levels are elevated in SLE and, despite its potent immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory activity, it has been proposed that, paradoxically, IL-10 has a role in disease pathogenesis. Although IL-10 has been shown to promote autoantibody production in models of lupus by enhancing B cell activation and differentiation, we identified a novel mechanism by which IL-10 potentiates immune-mediated injury. In this study we show that in SLE, the capacity of IL-10 to suppress production of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-6, by myeloid lineage cells is attenuated. TNFα and IL-6 have been implicated in promoting autoimmunity and tissue inflammation in SLE, and our finding of diminished downregulation of immune complex-induced inflammatory cytokine production by IL-10 argues that a defect in IL-10 homeostatic function contributes to SLE pathogenesis. Furthermore, we identify a basis for this resistance to the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10; IFNα, a cytokine implicated in the pathogenesis of SLE, decreases the capacity of IL-10 to suppress inflammation.

Because immune complexes play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of SLE and they can alter IL-10 signaling, we considered the possibility that their presence suppresses IL-10 responses in SLE monocytes. We found consistent inhibition of IL-10 signaling by HIg in control monocytes. Immune complexes abrogated the response to endogenously produced IL-10, while LPS did not have this effect. Such IL-10 dysfunction is likely to be important in tissues that contain extensive immune complex deposits, such as lupus glomeruli, where attenuation of responses to endogenous IL-10 promotes unopposed production of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNFα and IL-6. There is emerging evidence that TNFα promotes inflammation in kidneys of lupus patients (20) and anti-TNFα therapy was efficacious in an open label trial in refractory lupus nephritis (21). IL-6 release from peripheral mononuclear cells is associated with increased disease activity and IL-6 levels fall in lupus nephritis patients responding to treatment (22). We propose a new means by which immune complexes contribute to tissue injury in SLE. By blunting effects of IL-10, they allow unrestrained amplification of inflammatory pathways.

Our data are the first to show that monocytes from SLE patients are less responsive to the immunosuppressive effect of IL-10 in the presence of immune complexes. SLE monocytes produced more TNFα and IL-6 in response to HIg despite comparable amounts of IL-10, suggesting that endogenously produced IL-10 may not effectively suppress the inflammatory response of lupus monocytes. Furthermore, addition of exogenous IL-10 was a less potent inhibitor of HIg-induced TNFα and IL-6 production in SLE monocytes than in controls. Although HIg downregulated IL-10R expression in control monoyctes, IL-10R expression is not decreased in freshly isolated SLE monocytes, suggesting immune complex engagement in vivo does not explain the limited suppressive effects of IL-10 we observed in vitro. Our findings are in agreement with previous reports showing similar levels of IL-10R expression in SLE compared to control monocytes (18).

To understand the mechanism of exaggerated inhibition of IL-10 signaling in immune complex-stimulated SLE monocytes, we explored the potential role of cytokines that are associated with SLE pathogenesis and known to alter IL-10 function. Specifically, we focused on IFNα, whose presence in SLE has been identified by characteristic gene expression profiles (19). We found that IFNα decreased responses of control monocytes to IL-10 and recapitulated the SLE monocyte phenotype, consistent with a previous study that showed IFNα conferred a pro-inflammatory gain of function on IL-10 (23). We posit that the decreased response to IL-10 in SLE monocytes is the result of chronic exposure to IFNα in vivo. Indeed, our data show that in IFNα-primed monocytes IL-10 is relatively ineffective in suppressing HIg-induced IL-6 production. Thus, induction of resistance to the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 may be a new pathogenic role for IFNα in SLE.

Our data indicate that immune complexes and IFNα regulate IL-10 responses and provide insights into the early stages of disease development in lupus. Inappropriately suppressed IL-10 function permits uncontrolled autoantibody-mediated injury. A more complete understanding of the interplay between immune complexes, IL-10 and IFNα may identify therapeutic targets for limiting tissue damage.

Figure 4. Effect of IL-10 on monocytes primed with IFNα.

CD14+ monocytes from healthy donors were primed with M-CSF (10 ng/ml) or M-CSF plus IFNα (200 u/ml) for 16 hours. Cells were then treated with HIg (325 μg/ml) for three hours, in the presence or absence of IL-10 (20 ng/ml). All experiments were done in pairs. IL-6 mRNA was measured by quantitative real time PCR, with results normalized to the values for GAPDH. Suppression rate of IL-6 gene expression by IL-10 was compared between M-CSF and M-CSF+IFNα groups. * p=0.05

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 17 SLE patients

| Female sex, % | 88 |

| Age, mean ± SD years | 45 ± 13 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 47.1 |

| African American | 11.8 |

| Hispanic | 35.2 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5.9 |

| Disease duration, mean ± SD years | 18 ± 12 |

| Renal involvement, % | 41 |

| Prednisone therapy, % | 71 |

| Hydroxychloroquine, % | 76 |

| Azathioprine, % | 12 |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil, % | 18 |

| Cyclophosphamide, % | 6 |

| SLEDAI score, mean ± SD (range) | 0 ± 3 (0–8) |

SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; SLEDAI: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Mary Kirkland Center for Lupus Research at Hospital for Special Surgery (JES and LI) and by grants from NIH (LI).

REFERENCES

- 1.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annual Review of Immunology. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasama T, Strieter RM, Lukacs NW, Burdick MD, Kunkel SL. Regulation of neutrophil-derived chemokine expression by IL-10. J Immunol. 1994;152(7):3559–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding L, Linsley PS, Huang LY, Germain RN, Shevach EM. IL-10 inhibits macrophage costimulatory activity by selectively inhibiting the up-regulation of B7 expression. J Immunol. 1993;151(3):1224–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houssiau FA, Lefebvre C, Vanden Berghe M, Lambert M, Devogelaer JP, Renauld JC. Serum interleukin 10 titers in systemic lupus erythematosus reflect disease activity. Lupus. 1995;4(5):393–5. doi: 10.1177/096120339500400510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lazarus M, Hajeer AH, Turner D, Sinnott P, Worthington J, Ollier WE. Genetic variation in the interleukin 10 gene promoter and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(12):2314–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mok CC, Lanchbury JS, Chan DW, Lau CS. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms in Southern Chinese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41(6):1090–5. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199806)41:6<1090::AID-ART16>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Llorente L, Richaud-Patin Y, Wijdenes J, Alcocer-Varela J, Maillot MC, Durand-Gasselin I. Spontaneous production of interleukin-10 by B lymphocytes and monocytes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1993;4(6):421–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gröndal G, Kristjansdottir H, Gunnlaugsdottir B, Arnason A, Lundberg I, Klareskog L. Increased number of interleukin-10-producing cells in systemic lupus erythematosus patients and their first-degree relatives and spouses in Icelandic multicase families. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(8):1649–54. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1649::AID-ANR13>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Llorente L, Richaud-Patin Y, Couderc J, Alarcon-Segovia D, Ruiz-Soto R, Alcocer-Castillejos N. Dysregulation of interleukin-10 production in relatives of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(8):1429–35. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llorente L, Zou W, Levy Y, Richaud-Patin Y, Wijdenes J, Alcocer-Varela J, Morel-Fourrier B. Role of interleukin 10 in the B lymphocyte hyperactivity and autoantibody production of human systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. 1995;181(3):839–44. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Llorente L, Richaud-Patin Y, García-Padilla C, Claret E, Jakez-Ocampo J, Cardiel MH. Clinical and biologic effects of anti-interleukin-10 monoclonal antibody administration in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(8):1790–800. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1790::AID-ANR15>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salmon JE, Pricop L. Human receptors for immunoglobulin G: key elements in the pathogenesis of rheumatic disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(4):739–50. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200104)44:4<739::AID-ANR129>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berger S, Balló H, Stutte HJ. Immune complex-induced interleukin-6, interleukin-10 and prostaglandin secretion by human monocytes: a network of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines dependent on the antigen:antibody ratio. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26(6):1297–301. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polat GL, Laufer J, Fabian I, Passwell JH. Cross-linking of monocyte plasma membrane Fc alpha, Fc gamma or mannose receptors induces TNF production. Immunology. 1993;80(2):287–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Debets JM, Van der Linden CJ, Dieteren IE, Leeuwenberg JF, Buurman WA. Fc-receptor cross-linking induces rapid secretion of tumor necrosis factor (cachectin) by human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol. 1998;141(4):1197–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson CF, Gerber JS, Mosser DM. Modulating macrophage function with IgG immune complexes. J Endotoxin Res. 2002;8(6):477–81. doi: 10.1179/096805102125001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji JD, Tassiulas I, Park-Min KH, Aydin A, Mecklenbrauker I, Tarakhovsky A. Inhibition of interleukin 10 signaling after Fc receptor ligation and during rheumatoid arthritis. J Exp Med. 2003;197(11):1573–83. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cairns AP, Crockard AD, Bell AL. Interleukin-10 receptor expression in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2003;21(1):83–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baechler EC, Batliwalla FM, Karypis G, Gaffney PM, Ortmann WA, Espe KJ. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2610–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337679100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aringer M, Smolen JS. The role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(1):202. doi: 10.1186/ar2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aringer M, Houssiau F, Gordon C, Graninger WB, Voll RE, Rath E. Adverse events and efficacy of TNF-alpha blockade with infliximab in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: long-term follow-up of 13 patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(11):1451–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esposito P, Balletta MM, Procino A, Postiglione L, Memoli B. Interleukin-6 release from peripheral mononuclear cells is associated to disease activity and treatment response in patients with lupus nephritis. Lupus. 2009;18(14):1329–30. doi: 10.1177/0961203309106183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharif MN, Tassiulas I, Hu Y, Mecklenbräuker I, Tarakhovsky A, Ivashkiv LB. IFN-alpha priming results in a gain of proinflammatory function by IL-10: implications for systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):6476–81. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]