Abstract

Both innate and adaptive immune cells are actively involved in the initiation and destruction of allotransplants, there is a true need now to look beyond T cells in the allograft response, examining various non-T cell types in transplant models and how such cell types interact with T cells in determining the fate of an allograft. Studies in this area may lead to further improvement in transplant outcomes.

SUMMARY

The “T cell-centric paradigm” has dominated transplant research for decades. While T cells are undeniably quintessential in allograft rejection, recent studies have demonstrated unexpected roles for non-T cells such as NK cells, B cells, macrophage and mast cells in regulating transplant outcomes. It has been shown that depending on models, context, and tolerizing protocols, the innate immune cells contribute significantly to both graft rejection and graft acceptance. Some innate immune cells are potent inflammatory cells directly mediating graft injury while others regulate effector programs of alloreactive T cells and ultimately determine whether the graft is rejected or accepted. Furthermore, when properly activated, some innate immune cells promote the induction of Foxp3+ Tregs whereas others readily kill them, thereby differentially affecting the induction of tolerance. In addition, B cells can induce graft damage by producing alloantibodies or by promoting T cell activation. However, B cells also contribute to transplant tolerance by acting as regulatory cells or by stimulating Foxp3+ Tregs. These new findings unravel unexpected complexities for non-T cells in transplant models and may have important clinical implications. In this overview, we highlight recent advances on the role of B cells, NK cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages in the allograft response, and discuss whether such cells can be therapeutically targeted for the induction of transplant tolerance.

Keywords: Innate immunity, NK cells, dendritic cells, tolerance, transplantation

Introduction

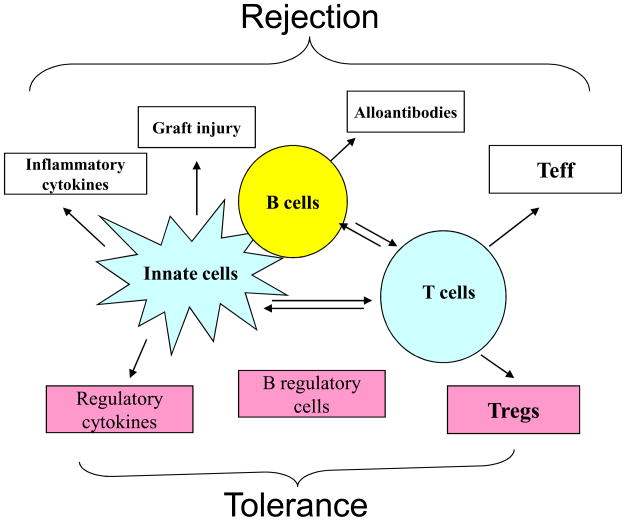

T cells are central to transplant rejection, thus preventing T cells from destroying the allografts remains an important area of transplant research. However, graft rejection involves many other cell types besides T cells; and the contribution of non-T cells to transplant outcomes (i.e., rejection or acceptance) has been increasingly appreciated (1). In fact, non-T cells, especially B cells, NK cells, macrophages and mast cells, exhibit broad impacts on graft rejection and graft acceptance (Fig 1). Such cells influence the allograft response in several different ways: some innate immune cells act as potent inflammatory cells promoting rejection by directly damaging the graft; others regulate differentiation of T effector cells by the virtue of their cytokine production, thus affecting the nature of the rejection response or the sensitivity to tolerizing therapies. In addition, some cell types directly control T cell priming by acting as APCs whereas others promote tolerance induction by killing donor APCs (2). Importantly, the cytokine milieu created by the activation of innate immune cells can be detrimental to the induction of Foxp3+ Tregs, a key cell type in transplant tolerance (3). It should be noted that the graft itself can also influence both non-T cells and T cells involved in graft damage or graft acceptance. Transplantation is inevitably associated with tissue injury due to graft ischemia-reperfusion, inflammation, drug toxicity or rejection, which often creates a highly inflammatory environment within the graft. Cytokines and endogenous factors released during such pro-inflammatory responses can augment the activation of both innate and adaptive immune cells in the rejection response. Thus, understanding precisely the role of non-T cells in transplant models and the in vivo conditions that control their pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties as well as their complex interactions with T cells becomes an interesting and important issue.

Fig 1.

Cross-talk of non-T cells and T cells in alloimmune responses. Non-T cells can directly damage the graft or indirectly by modifying the T cell programs.

In this overview, we will review recent advances in our understanding of the role of B cells, NK cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells in transplant models, highlighting their roles in transplant rejection and tolerance induction as well as challenges in targeting such cells in the induction of transplant tolerance.

The role of B cells in transplant models

B cells are a major cell type in the adaptive immune system and are primarily involved in humoral immunity. B cells are developed in the bone marrow and further matured in the spleen. In the periphery, B cells consist of many different subsets with striking differences in phenotype, function, and anatomic locations in vivo (4, 5). In essence, B cells can be broadly divided into B1 cells and B2 cells. Besides sharing the common B cell markers, B1 cells are phenotypically identified as B220lowCD5+ cells whereas B2 cells are B220highCD5− cells. In addition, B1 cells are located primarily in the peritoneal cavity while B2 cells reside in the spleen, lymph nodes, and gut-associated lymphoid tissues (6). B2 cells are extremely heterogeneous and are composed of mature B cells, marginal zone B cells, germinal center B cells, plasma cells, and memory B cells. Memory B cells and plasma cells can also be found in extra-lymphoid tissues. The exact function of B1 cells is unclear, but they may be involved in certain autoimmune diseases. The B2 cells are the cell types involved in classical humoral immunity against antigens including alloantigens (7).

With the exception of plasma cells, B cells do not seem to acquire cytopathic effector programs that directly cause graft injury. However, B cells can contribute to graft damage via multiple pathways and mechanisms. It is well recognized that B cells are potent producers of anti-donor antibodies, and these antibodies are known to induce several forms of graft injury, which include hype-acute rejection, acute humoral rejection, and chronic rejection (8). In fact, deposition of anti-donor antibodies in transplanted grafts has been shown to be associated with high incidence of chronic rejection and poor long-term graft outcomes in the clinic, and in most cases even in the presence of potent immunosuppression (9). Alloantibodies have become a major concern in the clinic, as current immunosuppressive drugs that primarily target T cells are not effective in inhibiting B cell production of antibodies (10). Mechanistically, alloantibodies mediate graft damage via both complement dependent and independent pathways, and activation of complements can trigger intense tissue inflammation and graft damage. In addition, B cells also mediate graft damage by promoting activation and differentiation of alloreactive T cells. In fact, B cells constitute the largest population of APCs in the immune system (11). In some settings, B cells are critically involved in the generation of memory T cells (12). The induction of memory T cells is a significant issue, as memory T cells are known to resist tolerance induction in transplant models (13). Furthermore, memory B cells themselves have been shown to resist tolerance induction by stimulating the activation of T cells (14). Importantly, in two clinical trails of tolerance induction, one involving broad T cell depletion and the other using the bone marrow chimeric approach, activation of B cells and the subsequent development of humoral response has emerged as a significant barrier to graft survival (15). These findings led to the belief (and also the practice in the clinic) that aggressive B cell depletion may be beneficial in promoting transplant tolerance. However, this belief is challenged by several recent findings that B cells, at least certain B cell subsets, are actually required for the induction of transplant tolerance. For example, anti-CD45 mAb can produce long-term allograft survival in wt mice but not in B cell deficient mice (16), suggesting that B cells can be actually tolerogenic. In a cohort of kidney transplant patients who are off immunosuppression for a prolonged period of time, stable graft survival is associated with a strong B cell transcriptional signature (17). For this reason, B cells are now under intense scrutiny, not for graft rejection but for allograft tolerance. Interestingly, some B cells can act as regulatory cells by producing IL-10 (18) while others promote active immune regulation by inducing Foxp3+ Tregs (6), which are key mechanisms of peripheral tolerance (19). An important message from these studies is that broad B cell depletion will not always be beneficial in transplant settings, and under certain conditions, this approach may be counter-productive because of striking differences in B cell function.

Perhaps a different strategy is needed in targeting B cells to promote transplant survival and such a strategy should be guided by key differences in B cell subsets and function. In a broad sense, depletion therapies should selectively and specifically target plasma cells committed to alloantibody production as well as alloreactive memory B cells, and B cells that are actively involved in priming the activation of alloreactive T cells need to be inhibited. Importantly, B cell depletion and inhibition approaches should not interfere with those with regulatory properties. Clearly, this strategy demands a detailed understanding of the mechanisms governing various aspects of B cell subsets and function in vivo.

NK cells in graft rejection and survival

NK cells, a key cell type in the innate immune system, are frequently found in rejecting allografts. But the exact role of NK cells in solid organ transplantation has defied our understanding until recently. In various transplant models, NK cells have been shown to contribute to both allograft rejection and transplant tolerance (20) due to unique features of NK cells and differences in NK functions (21).

NK cells express a unique self-non-self recognition system that makes them highly relevant to transplant models. In essence, individual NK cells have both stimulatory and inhibitory receptors on the cell surface, and signals from both types of receptors are required to establish NK tolerance to autologous cells (22). The inhibitory receptors include killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIR) in humans and the lectin-like Ly49 receptors in mice. In addition, NKG2A and CD94 usually form heterodimers on the cell surface and function as inhibitory NK receptors (23). An important feature of this system is that the ligands for such inhibitory receptors are self MHC class I molecules, and therefore NK cells are in a state of dominant inhibition by constantly engaging the ubiquitously expressed self MHC class I molecules.

In transplant models, NK cells can readily recognize MHC incompatible allogeneic cells via “missing self” or “missing ligand” recognition (24), as allogeneic cells lack self MHC class I molecules to engage NK inhibitory receptors. This type of response triggers NK activation, which includes cytolytic activities and production of potent pro-inflammatory cytokines. Such “alloreactive” NK cells have been extensively analyzed in bone marrow transplant models in which NK cells promptly reject MHC mismatched bone marrow stem cells (24). In selected models, NK cells are also involved in rejection of solid organ transplants. For example, NK cells are key effector cells in rejection of heart xenografts (25). In addition, NK cells play a critical role in heart allograft rejection in CD28 knockout mice (26, 27), they also contribute to chronic transplant vasculopathy in a hybrid resistant model where T cell alloreactivity to the transplant is avoided (28). In those studies, the recipient mice possess normal adaptive immune cells, thus it remains unclear whether NK cells directly mediate graft damage or indirectly by promoting the alloreactivity of adaptive immune cells or both. In immunodeficient mice (absence of T cells and B cells), NK cells by themselves fail to induce allograft rejection, but acute allograft rejection can be triggered by exposing NK cells to IL-15 (29), which is known to stimulate expansion and maturation of NK cells (30). This suggests an important but conditional role for NK cells in solid allograft rejection. Interestingly, NK cells can acquire “adaptive features” following IL-15 stimulation that are traditionally ascribed to T cells, such as the generation of memory responses (31, 32). Hence, it remains possible that “memory NK cells” may act as potent effector cells in allograft rejection, and prevention of NK cells from acquiring “memory” phenotypes might be important in tolerance induction.

NK cells also play an unexpected role in the induction of transplant tolerance (2, 33). This initial finding was counterintuitive or paradoxical, given the role of NK cells as killers and inflammatory cells. We found that NK cells control of life and death of graft-derived donor cells including donor dendritic cells, and by killing donor dendritic cells through “missing self” or “missing ligand” recognition, NK cells limit the priming of alloreactive T cells in transplant recipients by the direct pathway (2). Moreover, killing of donor cells may also facilitate the activation of T cells by the indirect pathway (34), which is considered to be permissive to tolerance induction (35). Thus in the absence of NK cells, donor dendritic cells survive much better in allogeneic hosts, and in this setting, proliferation of alloreactive T cells in vivo is extremely robust (36). This is consistent with the notion that direct stimulation of host T cells by donor dendritic cells activates a large mass of alloreactive clones (37). In other models, NK cells have been shown to either activate self APCs or kill those that have reduced expression of MHC class I (38), thereby positively or negatively regulating immune responses. The implication of this effect on host APCs in transplant models remains to be examined. There are probably other targets for NK cells. NK cells can directly inhibit or kill activated T cells (39). Recently, NK cells have been shown to control the induction of Foxp3+ Tregs (40), which will undoubtedly affect the status of tolerance. From a therapeutic standpoint, strategies that inhibit the pro-inflammatory effects of NK cells while spare or even boost their immunoregulatory properties are clearly desirable in tolerance induction. Studies in this area should deserve more attentions.

Macrophages, monocytes, and mast cells

Macrophages are constituents of inflammatory infiltrates; they are a prominent cell type in rejecting allografts (41). Macrophages and monocytes are rapidly recruited to sites of inflammation including allografts; they are highly responsive to cytokines such as interferons and also potent producers of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1, IL-6, TNF-a, which are known to enhance both innate and adaptive immune responses (42). Such an inflammatory milieu prevents the induction of Foxp3+ Tregs, but instead promotes differentiation of inflammatory Th17 cells (43, 44). Hence, most studies thus far suggest a pro-inflammatory role for macrophages/monocytes in transplant models. In fact, macrophages and monocytes are closely involved in graft rejection and/or resistance to tolerance induction. In an animal model of chronic allograft rejection, macrophages are shown to infiltrate the heart allografts and contribute to transplant vasculopathy (45). In this model, partial depletion of macrophages using carrageenan reduced the severity of chronic rejection (45). Moreover, in selected clinical trials involving broad T cell depletion, some kidney transplant patients experience episodes of acute rejection even in the presence of aggressive T cell depletion therapies, and histologically, this type of rejection is associated with intense monocytic infiltrations (46), suggesting a key role for macrophages/monocytes in graft damage. It has been recognized that focal aggregates of immune cells are frequently present in stable transplants with no obvious graft damage (benign infiltrates), but macrophages can turn such benign infiltrates to aggressive ones, which often cause graft injury. It seems that macrophages may control the cytopathic nature of cellular infiltrates in organ transplants.

In some models, macrophages can have regulatory roles promoting immune tolerance. For example, when macrophages are driven to an activated status by IFN-g, macrophages prevent autoimmune colitis by inducing and expanding Foxp3+ Tregs (47). Whether this is also the case in transplant models remains to be determined. Additionally, under certain conditions, mast cells, which are inherently pro-inflammatory, are unexpectedly involved in the induction of transplant tolerance (48). It appears that mast cells are recruited to the graft by Foxp3+ Tregs through the production of IL-9 to maintain tolerance (48). But tolerance in this setting is fragile, as mast cell degranulation often induces prompt rejection of otherwise tolerant graft (49).

Dendritic cells in transplant outcomes

DCs are intimately involved in both productive immunity and immune tolerance. Thus there is tremendous enthusiasm in identifying or generating the right types of DCs that will aid in the induction of transplant tolerance (50). Based on a combination of cell surface markers, various subsets of DCs have been reported in both humans and mice, each has unique features and functional attributes. For example, myeloid DCs are identified as CD11c+CD11b+CD205− cells whereas the lymphoid DCs are CD11c+CD205+CD11b− cells. Both subsets are also called conventional DCs and are potent stimulators of T cell proliferation and effector differentiation. Plasmacytoid DCs distinguish themselves from others by expressing CD11c+B220+PDCA+ cells (51). In the lymphoid organs, different DC subsets are located at different anatomical sites, probably due to differential expression of chemokines, chemokine receptors as well as certain homing receptors. Also, DC subsets show differences in their ability to stimulate T effector cells and Foxp3+ Tregs, most likely due to differences in the expression of costimulatory ligands and/or production of cytokines (52). These differences suggest a division of functions among DC subsets in vivo. However, this notion is not absolute, when DCs are further matured under inflammatory conditions, the division of functions among DC subsets is less striking, at least in vitro (53).

There are two broad approaches in modulating DCs for tolerance induction, and each has advantages and challenges (50). The first is to create “tolerogenic DCs” in vitro and use them as a cell therapy in vivo. Both genetic and pharmacological means have been tried to induce and expand such cells, which include transgenic expression of coinhibitory molecules and immune regulatory cytokines in DCs or alteration in DC functions in vitro with mTOR inhibitors (54). Depending on the models, such tailor-made DCs have demonstrated efficacy in extending graft survival when combined with other immune interventions such as costimulatory blockade (55). However, challenges remain, if donor DCs are used, they will be undoubtedly killed by recipient NK cells upon passive transfer (2). In the case of using syngeneic DCs, they need to pick up the right donor antigens and deliver them in a tolerogenic form to alloreactive T cells, which is not always the case in vivo. Also, it proves difficult to know how stable those in vitro generated DCs are in vivo, and whether they home to the right locations where they work the best to achieve tolerance. Another approach is to target “tolerogenic DCs” in vivo, by taking advantage of different features of DC subsets and various tolerance induction protocols. Clearly, there is some success in this regard (56). But challenges are equally daunting in developing an effective and clinically applicable DC targeting protocols because the alloimmunity is so dynamic, and tolerance demands donor antigen specificity and durability.

Conclusions

The immune responses to organ transplants are incredibly complex, both innate and adaptive immune cells are intimately involved in this process. Thus, prevention of rejection and ultimately the induction of tolerance most likely requires comprehensive strategies targeting both innate and adaptive immune cells that are critically involved in the rejection response. It is time now for the transplant community to take a broad look at how the immune system as a whole responds to an allotransplant and reassess our understanding of these responses in a dynamic and integrated manner. In the past decades, we have gained considerable knowledge concerning the role of T cells in transplant models and devised various effective strategies to target such T cells. We are just beginning to appreciate the importance and complexity of non-T cells in transplant models, and our approaches to effectively and specifically modulate such cells for transplant tolerance are very much limited. This limitation hinders our ability to create transplant tolerance in the clinic.

Studies of non-T cells will continue to be fraught with challenges and surprises. The same cell type can promote transplant rejection or facilitate tolerance induction depending on models, context, and tolerizing therapies. Thus, targeting such cells for the induction of transplant tolerance is unlikely to be straightforward. We are ill informed about the complex interactions amongst diverse subsets of non-T cells in vivo in transplant rejection and tolerance induction, and how such interactions will affect the effector and the regulatory programs of alloreactive T cells. This complexity presents both challenges and opportunities in the induction of transplant tolerance. There are several areas that require immediate attention, which include mechanisms that regulate various aspects of innate immune responses to allografts, how innate immune cells interact with each other and then regulate T effector cells or vice versa; the impact of innate immunity on induction and stability of immune regulatory cells. These are important but under-studied areas, but the potential impact on developing better tolerizing strategies and new diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers will be significant.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Xian C. Li is supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International.

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- DC

dendritic cells

- KIR

Killer-cell Immunoglobulin-like Receptors

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- NK

natural killer cells

References

- 1.Alegre ML, Florquin S, Goldman M. Cellular mechanisms underlying acute graft rejection: time for reassessment. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:563. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu G, Xu X, Vu MD, Kilpatrick ED, Li XC. NK cells promote transplant tolerance by killing donor antigen-presenting cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203 (8):1851. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Plasticity of CD4(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:281. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nimmeriahn F, Ravetch JV. Fc receptors as regulators of immunity. Advances in Immunology. 2007;96:179. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(07)96005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacquot S. CD27/CD70 interactions regulate T dependent B cell differentiation. Immunol Rev. 2000;21:23. doi: 10.1385/IR:21:1:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xuemei Z, Wenda G, Nicolas D, et al. Reciprocal generation of Th1/Th17 and Treg cells by B1 and B2 B cells. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37 (9):2400. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacKay F, Schneider P, Rennert P, Browing J. BAFF and APRIL: a tutorial on B cell survival. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:231. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terasaki PI, Cai J. Humoral theory of transplantation: further evidence. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:541. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwun J, Knechtle SJ. Overcoming Chronic Rejection-Can it B? Transplantation. 2009;88:955. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181b96646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halloran PF. Immunosuppressive Drugs for Kidney Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2004;351 (26):2715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra033540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKenzie D. Alloantigen presentation by B cells: requirement for IL-1 and IL-6. Journal of Immunology. 1988;141:2907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitmire JK, Asano MS, Kaech SM, et al. Requirement of B Cells for Generating CD4+ T Cell Memory. Journal of Immunology. 2009;182 (4):1868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valujskikh A, Li XC. Frontiers in Nephrology: T Cell Memory as a Barrier to Transplant Tolerance. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18 (8):2252. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burns AM, Ma L, Li Y, et al. Memory Alloreactive B Cells and Alloantibodies Prevent Anti-CD154-Mediated Allograft Acceptance. J Immunol. 2009;182 (3):1314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porcheray F, Wong W, Saidman SL, et al. B-Cell Immunity in the Context of T-Cell Tolerance after Combined Kidney and Bone Marrow Transplantation in Humans. American Journal of Transplantation. 2009;9 (9):2126. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng S, Moore DJ, Huang X, et al. Cutting Edge: Transplant Tolerance Induced by Anti-CD45RB Requires B Lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2007;178 (10):6028. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zarkhin V, Chalasani G, Sarwal MM. The yin and yang of B cells in graft rejection and tolerance. Transplant Rev. 2010;24 (2):67. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rafei M, Hsieh J, Zehntner S, et al. A granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-15 fusokine induces a regulatory B cell population with immune suppressive properties. Nature Medicine. 2009;15:1038. doi: 10.1038/nm.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood KJ, Sakaguchi S. Regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3 (3):199. doi: 10.1038/nri1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kroemer A, Edtinger K, Li XC. The innate NK cells in transplant rejection and tolerance induction. Curr Opin Organ Transplantation. 2008;13:339. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e3283061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vivier E, Tomasello E, Baratin M, Walzer T, Ugolini S. Functions of natural killer cells. Nature Immunology. 2008;9:503. doi: 10.1038/ni1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanier LL. NK cell recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:225. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walzer T, Jaeger S, Chaix J, Vivier E. Natural killer cells: from CD3(-)NKp46(+) to post-genomics meta-analyses. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:365. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruggeri L, Mancusi A, Capanni M, Martelli M, Velardi A. Exploitation of allorective NK cells in adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:211. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin Y, Vandeputte M, Waer M. Natural killer cell- and macrophage-mediated rejection of concordant xenografts in the absence of T and B cell responses. J Immunol. 1997;158 (12):5658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maier S, Tertilt C, Chambron N, et al. Inhibition of natural killer cells results in acceptance of cardiac allografts in CD28−/− mice. Nature Medicine. 2001;7:557. doi: 10.1038/87880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McNerney ME, Lee KM, Zhou P, et al. Role of natural killer cell subsets in cardiac allograft rejection. American Journal of Transplantation. 2006;6:505. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uehara S, Chase CM, Kitchens WH, et al. NK Cells Can Trigger Allograft Vasculopathy: The Role of Hybrid Resistance in Solid Organ Allografts. J Immunol. 2005;175 (5):3424. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kroemer A, Xiao X, Degauque N, et al. The Innate NK Cells, Allograft Rejection, and a Key Role for IL-15. J Immunol. 2008;180 (12):7818. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fehniger TA, Caligiuri MA. Interleukin-15: biology and relevance to human disease. Blood. 2001;97:14. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper MA, Elliott JM, Keyel PA, Yang L, Carrero JA, Yokoyama WM. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106 (6):1915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813192106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun JC, Beilke JN, Lanier LL. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature. 2009;457:557. doi: 10.1038/nature07665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beilke JN, Kuhl NR, Kaer LV, Gill RG. NK cells promote islet allograft tolerance via a perforin-dependent mechanism. Nature Medicine. 2005;11:1059. doi: 10.1038/nm1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garrod KR, Liu F-C, Forrest LE, Parker I, Kang S-M, Cahalan MD. NK Cell Patrolling and Elimination of Donor-Derived Dendritic Cells Favor Indirect Alloreactivity. Journal of Immunology. 2010;184 (5):2329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rulifson IC, Szot GL, Palmer E, Bluestone JA. Inability to induce tolerance through direct antigen presentation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:510. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.20604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laffont S, Seillet C, Ortaldo J, Coudert JD, Guery J-C. Natural killer cells recruited into lymph nodes inhibit alloreactive T-cell activation through perforin-mediated killing of donor allogeneic dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112 (3):661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li XC, Strom TB, Turka LA, Wells AD. T cell death and transplantation tolerance. Immunity. 2001;14:407. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00121-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Degli-Esposti MA, Smyth MJ. Close encounters of different kinds: Dendritic cells and NK cells take centre stage. Nature Rev Immunol. 2005;5:112. doi: 10.1038/nri1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rabinovich BA, Shannon J, Su RC, Miller RG. Stress renders T cell blasts sensitive to killing by activated syngeneic NK cells. Journal of Immunology. 2000;165:2390. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy S, Barnes PF, Garg A, Wu S, Cosman D, Vankayalapati R. NK Cells Lyse T Regulatory Cells That Expand in Response to an Intracellular Pathogen. J Immunol. 2008;180 (3):1729. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Langrehr JMH, BG, White DA, Hoffman RA, Simmons RA. Macrophages produce nitric oxide at allograft sites. Annals of Surgery. 1993;218:159. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199308000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kimura A, Naka T, Kishimoto T. IL-6-dependent and -independent pathways in the development of interleukin 17-producing T helper cells. PNAS. 2007;104 (29):12099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705268104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burlingham WJ, Love RB, Jankowska-Gan E, et al. IL-17 dependent cellular immunity to collagen type V predisposes to obliterative bronchiolitis in human lung transplants. J Clin Invest. 2007:JCI28031. doi: 10.1172/JCI28031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong C. TH17 cells in development: an updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:337. doi: 10.1038/nri2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitchens WH, Chase CM, Uehara S, et al. Macrophage depletion suppresses cardiac allograft vasculopathy in mice. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2675. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knechtle S, Pirsch JD, Fechner JH, et al. Campath-1H induction plus rapamycin monotherapy for renal transplantation: results of a pilot study. Am J Transplant. 2003;3 (6):643. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brem-Exner BG, Sattler C, Hutchinson JA, et al. Macrophages Driven to a Novel State of Activation Have Anti-Inflammatory Properties in Mice. J Immunol. 2008;180 (1):335. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu LF, Lind EF, Gondek DC, et al. Mast cells are essential intermediaties in regulatory T-cell tolerance. Nature. 2006;442:997. doi: 10.1038/nature05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Vries VC, Wasiuk A, Bennett KA, et al. Mast cell degranulation breaks peripheral tolerance. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:2270. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shortman K, Liu YJ. Mouse and human dendritic cell subtypes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:151. doi: 10.1038/nri746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ito T, Amakawa R, Inaba M, et al. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Regulate Th Cell Responses through OX40 Ligand and Type I IFNs. J Immunol. 2004;172 (7):4253. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shortman K, Naik SH. Steady state and inflammatory dendritic cell development. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:19. doi: 10.1038/nri1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turnquist HR, Raimondi G, Zahorchak AF, Fischer RT, Wang Z, Thomson AW. Rapamycin-Conditioned Dendritic Cells Are Poor Stimulators of Allogeneic CD4+ T Cells, but Enrich for Antigen-Specific Foxp3+ T Regulatory Cells and Promote Organ Transplant Tolerance. J Immunol. 2007;178 (11):7018. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Turnquist HR, Thomson AW. Taming the lions: manipulating dendritic cells for use as negative cellular vaccines in organ transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplantation. 2008;13:350. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328306116c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ochando JC, Homma C, Yang Y, et al. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nature Immunology. 2006;7:652. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]