Abstract

Little is known about the correlates and potential causes of very early drinking. The authors proposed this risk theory: (a) pubertal onset is associated with increased levels of positive urgency (the tendency to act rashly when experiencing intensely positive mood), negative urgency (the tendency to act rashly when distressed), and sensation seeking; (b) those traits predict increased endorsement of high-risk alcohol expectancies; (c) the expectancies predict drinker status among 5th graders; and (d) the apparent influence of positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking on drinker status is mediated by alcohol expectancies. The authors conducted a concurrent test of whether the relationships among these variables were consistent with the theory in a sample of 1,843 5th grade students. In a well-fitting structural model, their hypotheses were supported. Drinker status among 5th graders is not just a function of context and factors external to children: it is predictable from a combination of pubertal status, personality characteristics, and learned alcohol expectancies.

Risk Factors for Elementary School Drinking: Pubertal Status, Personality, and Alcohol Expectancies Concurrently Predict 5th Grade Alcohol Consumption

Researchers know far too little about pre-adolescent alcohol consumption (Donovan, 2007; Windle, Spear, Fuligni, et al., 2008; Zucker, Donovan, Masten, Mattson, & Moss, 2008.) Because such very early consumption predicts substance use disorders in adolescence and adulthood (Grant & Dawson, 1997; Labouvie, Bates, & Pandina, 1997), researchers have focused primarily on early drinking as a predictor of later problems. The correlates, and potential causes, of pre-adolescent drinking have received much less attention. It is quite likely true that key determinants of pre-adolescent drinking include contextual variables, such as access to alcohol and favorable parental attitudes toward consumption (Jackson, 1997; Jahonda & Cramond, 1972; Greenlund, Johnson, Webber, & Berenson, 1997), but we know little about the degree to which personal characteristics of children, including aspects of their personality and learning histories, also play a role in very early consumption. Recent advances have made it possible to measure two categories of risk factors in pre-adolescents: high-risk personality traits and high-risk psychosocial learning (Dunn & Goldman, 1998; Zapolski, Stairs, Settles, Combs, & Smith, in press). This paper reports the results of a cross-sectional test of a developmental model that integrates these risk factors with pubertal onset as concurrent predictors of drinker status among 1,843 5th graders.

To introduce this test, we briefly review what is known about drinking at this age, the apparent impact on drinking of (a) pubertal onset, (b) high-risk personality traits, and (c) high-risk psychosocial learning. We then offer our theoretical integration of these risk factors and the specific hypotheses that follow from this integration.

Pre-Adolescent Alcohol Consumption

The age at which individuals have their first drink is a robust predictor of subsequent alcohol abuse: among children who had their first drink at ages 11 or 12, 13.5% had alcohol abuse diagnoses and 15.9% had alcohol dependence diagnoses 10 years later. The rates of later alcohol use disorders decline steadily as a function of age of first drink: among those who first drank at age 19 or older, just 2% developed alcohol abuse diagnoses and 1% developed alcohol dependence diagnoses over the following 10 years (De Wit, Adlaf, Offord, & Ogborne, 2000). The relatively limited epidemiological data on the frequency with which children have consumed a drink (many children have had just sips or tastes, and that use is not predictive of future problems: Donovan & Molina, 2008) indicates that 9.8% of 4th graders, 16.1% of 5th graders, and 29.4% of 6th graders report having done so (Donovan, 2007). It thus appears that the late grade school or early middle school years are ones in which many children have their first direct experience with alcohol. At these early ages, there are few differences as a function of race or ethnicity, and a higher percentage of boys tend to report having consumed alcohol than girls (Donovan, 2007). Early pubertal onset is associated with earlier onset of alcohol use and substance use in adolescence (Westling, Andrews, Hampson, & Peterson, 2008; Zucker et al., 2008), although less is known about the relationship between pubertal status and pre-adolescent consumption.

Personality Risk Factors for Early Alcohol Use

In recent years, five different traits that are related to impulsive behavior have been identified: negative and positive urgency are the tendencies to act rashly when experiencing either distress or a very positive mood, respectively; sensation seeking is the tendency to seek out new and thrilling experiences; lack of planning is the tendency to act without thinking ahead; and lack of perseverance is the inability to remain focused on a task (Cyders & Smith, 2007; Whiteside & Lynam, 2001). When all five traits are examined together in young adults, the two urgency traits consistently predict problem drinking and sensation seeking predicts the frequency of consumption, and these effects have been shown in both concurrent and prospective prediction (Cyders, Flory, Rainer, & Smith, 2007, 2009; see also Miller, Flory, Lynam, & Leukefeld, 2003). In contrast, lack of planning and lack of perseverance tend not to add predictive power to either criterion, beyond prediction by the urgency traits and sensation seeking (Cyders et al., 2009). Zapolski et al. (2008, in press) showed that the five traits can be measured in pre-adolescent children: they found convergent validity across assessment method, discriminant validity between the traits, and differential correlates of the traits consistent with theory. As a result, it is now possible to test hypotheses concerning the relationships between this set of traits and very early, i.e. pre-adolescent, alcohol consumption.

Psychosocial Learning Risk Factors for Early Alcohol Use: Alcohol Expectancies

Expectancies are thought to represent summaries of one's learning history about the outcomes of one's behavioral choices (Bolles, 1972; Tolman, 1932). A substantial body of research has demonstrated that positive alcohol expectancies predict both increased drinking (Ouellette et al., 1999; Settles, Cyders, & Smith, in press; Smith et al., 1995) and the onset of adolescent problem drinking (Smith, 1994). Among 5th and 6th grade children, endorsement of expectancies that alcohol produces positive, social effects and wild and crazy effects are associated with alcohol consumption (Anderson, Smith, McCarthy, et al., 2005; Dunn & Goldman, 1998), and positive alcohol expectancies predicted subsequent increased drinking in 5th grade children (Goldberg, Halpern-Felsher, & Millstein, 2002). Experimental studies have also demonstrated that lowering expectancies leads to lower levels of alcohol consumption (Darkes & Goldman, 1993, 1998, but see Jones, Corbin, & Fromme, 2001). Thus, there is good evidence that alcohol expectancies predict future drinking and may play a causal role in alcohol consumption.

An Integrated Theory of Risk for Very Early Drinking

Following the onset of puberty, adolescents tend to experience (a) greater levels of emotional volatility than children or adults (Larson & Richards, 1994); (b) heightened negative affect (Allen & Matthews, 1997; Spear, 2000); (c) increases in rash action, particularly when experiencing intense positive and negative emotions (Luna & Sweeney, 2004; Steinberg, 2004); and (d) increases in risk-taking behaviors (Maggs & Hurrelmann, 1995; Moffitt, 1993). Researchers believe that these behavioral changes are a developmentally limited experience of adolescence, resulting (in part) from the combination of physical maturation following puberty and the lack of prefrontal cortex maturity during this period (Spear, 2000). These behavioral changes can be understood as expressions of developmentally heightened levels of positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking (see Cyders & Smith, 2008).

The theory of risk that underlies this investigation is as follows. Pubertal onset leads to increases in positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking. Individual differences on the traits, in turn, influence the learning process. Children high in negative urgency are more likely to learn that alcohol provides reinforcement that helps alleviate their distress. Alleviation of distress contributes to more positive social interactions; thus, children are prepared to learn that drinking increases positive social experiences. Children high in positive urgency are more likely to learn that drinking is associated with positive mood-based dyscontrol, and hence are prepared to learn that drinking is associated with wild and crazy behavior. Sensation seeking may lead to heightened learning of either type of expectancy. The theory that individual traits lead to individual differences in learning, thus increasing risk for addictive behaviors, is known as the acquired preparedness model of risk: as a function of trait factors, individuals are differentially prepared to acquire high risk expectancies (Smith & Anderson, 2001).

In this study, we tested whether the relationships among the predictors and drinking behavior were consistent with this theory. Thus, pubertal status would concurrently predict positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking, but would not predict lack of planning and lack of perseverance (thus providing a discriminant validity test of the model of pubertal influence). Pubertal status would concurrently predict endorsement of expectancies that alcohol provides positive social experiences and wild and crazy behavior, and that relationship would be mediated by the urgency traits and sensation seeking. Positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking would concurrently predict drinker status, and those relationships would be mediated by alcohol expectancy endorsement.

Of course, because this test was based on cross-sectional data, it is not a test of the temporal sequence of influences implied by the model. Rather, it is an initial test of whether the relationships among the variables are consistent with the model: if they are not, the viability of the model would be jeopardized. If they are consistent with the model, then longitudinal tests of the proposed temporal sequence are indicated.

Methods

Subjects

Participants in the study (n=1843) consisted of 5th grade students from urban, rural, and suburban backgrounds, all from public school systems. The sample was equally divided between boys (50.1%) and girls (49.9%). The breakdown of students by ethnicity was as follows: 61.6% European American, 17.0% African American, 6.9% Hispanic/Latino, 3% Asian American, and 11.5% of students reporting other ethnic backgrounds. The majority of the 5th graders, 66.8%, were 11years of age; 22.8% were 10 years of age, 10% were age 12, and both 9 and 13 year olds made up .2% of the participants.

Measures

The Pubertal Development Scale (PDS: Petersen et al., 1988). This scale consists of five questions for boys and five questions for girls. Sample questions are, for boys, “do you have facial hair yet?” and, for girls, “have you begun to have your period?” Individuals respond on a 4 point scale. The scale has acceptable reliability estimates (α's ranging from .67 to .76 for 11 year olds), and scores on it correlate highly with physician ratings and other forms of self-report (r values ranging from .61 to .67: Brooks-Gunn et al., 1987; Coleman & Coleman, 2002). The PDS permits dichotomous classifications as pre- pubertal or pubertal, with mean scores above 2.5 indicative of pubertal onset. As is common (e.g., Culbert, Burt, McGue, Iacono, & Klump, 2009), we used the dichotomous classification in the current study.

The UPPS-P-Child Version (Whiteside & Lynam, 2001; Zapolski et al., in press) was used to measure the five personality dispositions to rash action. The scales, with sample items are: negative urgency (“When I am upset I often act without thinking”), positive urgency (“When I am very happy, I can't stop myself from going overboard”), sensation seeking (“I like new, thrilling things, even if they are a little scary”), lack of planning (“I tend to blurt out things without thinking”), and lack of perseverance (“Once I get going on something I hate to stop,” which is reverse scored). There are eight items per scale, and responses are on a four-point likert scale, from “not at all like me” to “very much like me.” Zapolski et al. (in press) reported internal consistency reliability for four of the five scales (all but positive urgency), and values ranged from α = .81 to α = .90. In that study, the four scales showed good convergent and discriminant validity using multitrait, multimethod analysis. In the current sample, internal consistency reliability estimates for the five scales were: lack of planning, .77; negative urgency, .85; sensation seeking, .79; lack of perseverance, .65; and positive urgency, .89. Evidence for the validity of the child scales was reviewed briefly above: each scale predicted criteria consistent with theory and the scales predicted different criteria from each other.

Memory Model-Based Expectancy Questionnaire (MMBEQ: Dunn & Goldman, 1996) provides an extensive assessment of alcohol expectancies in children. We assessed four domains: positive social, negative arousal, sedation, and “wild and crazy” behaviors. The scale begins with the stem, “Drinking alcohol makes people ____.” Children then read items that complete the stem (e.g., “active,” “friendly,” “wild,” “mean”) and then circle one of four responses: “never,” “sometimes,” “usually,” or “always.” Thus, items are scored on a Likert-type scale. Each of the subscales are correlated with drinking levels and each is internally consistent (α's = .78 or higher: Dunn & Goldman, 1996, 1998). Sample items and current sample internal consistency reliability estimates are as follows: positive social, 18 items (“friendly,” “fun,” “outgoing”), α = .84; negative arousal, 7 items (“mad,” “mean”), α = .82; sedation, 7 items (“sleepy,” “slow”), α = .80; and wild and crazy (we used 5 of 7 items: “loud,” “crazy”), α = .73. The two items we dropped from this scale (Drinking alcohol makes people calm, and Drinking alcohol makes people quiet) are reverse scored. They had very low item-total correlations in this sample and so were removed.

The Drinking Styles Questionnaire (DSQ: Smith et. al., 1995) was used to measure self-reported drinking. The DSQ can provide scales assessing drinking/drunkenness and problem drinking, and there is good evidence for the reliability and validity of those scales in early adolescents, late adolescents, and adults (Settles et al., in press; Smith et al., 1995). For this young sample, we measured drinker status dichotomously. Children were classified as positive for drinking if they reported ever having consumed at least one drink, where a drink was defined as follows: “ . . . a ‘drink’ is more than just a sip or a taste. (A sip or a taste is just a small amount or part of someone else's drink or only a swallow or two. A drink would be more than that.)” The problem drinking scale was drawn from Smith et al. (1995) and asked about ever having experienced the problems referred to. We expanded the scale to include additional problems likely to occur at a higher base rate for children. We added 4 new items (for a total of 14), taken from Kahler, Strong, and Read (2005), who found that positive responses to these items occur with high frequency among adolescents (for example, “While drinking, I have said or done embarrassing things;” “I have felt very sick to my stomach or thrown up after drinking.”). We did not calculate a problem drinking score, due to the low base rates of reported problems, but we do provide information concerning the most frequently reported drinking problems among these 5th graders.

Procedure

Questionnaire Administration Procedures

The questionnaires were administered in 23 public elementary schools during school hours. A passive consent procedure was used. Each family was sent a letter, through the U.S. Mail, introducing the study. Families were asked to return an enclosed, stamped letter or call a phone number if they did not want their child to participate. Out of 1,988 5th graders in the participating schools, 1,843 participated in the study (92.7%). A total of 56 (2.8% of the families approached) declined to participate, 42 students (2.1%) declined assent, and 47 students (2.3%) did not participate for a variety of other reasons, such language disabilities that precluded completing the questionnaires. The procedure took 60 minutes or less. Upon completion, all participants were provided with information about local intervention services. This procedure was approved by the University's IRB and by the participating school systems.

Data Analytic Method

After reporting the frequency of 5th grade drinking for the sample as a whole, and testing whether drinking varied as a function of sex and race, we calculated Pearson product moment correlations among all the study variables (for the dichotomous variables, such as sex, the correlations were point biserial correlations). To test the core hypotheses of the study, we used structural equation modeling (SEM). Our theoretical model, including discriminant predictions and mediation hypotheses, was tested with a single, omnibus SEM model using MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004) and maximum likelihood estimation.

Prior to testing that overall model, we tested a measurement model to evaluate our representation of the five personality traits of negative urgency, positive urgency, sensation seeking, lack of planning, and lack of perseverance as latent variables. We measured them as latent variables because, for each variable, we understand the indicators of the variable to be expressions of a common, underlying construct. Using latent variable theory (Bollen, 2002; Borsboom, Mellenbergh, & Van Heerden, 2003), we view variability in indicator responses as effects of variability in the underlying construct. Each trait measure included 8 items. Floyd and Widaman (1995) recommended the use of item parcels with scales of this length. The use of item parcels has a number of measurement advantages.

First, when items are grouped into parcels, the impact of item content overlap among pairs of items is reduced (Floyd & Widaman, 1995). Second, the reliability of a parcel of items is greater than that of a single item, so parcels can serve as more stable indicators of a latent construct. Third, as combinations of items, parcels provide more scale points, thereby more closely approximating continuous measurement of the latent construct. Fourth, there is reduced risk of spuriously positive correlations, both because fewer correlations are being estimated and because each estimate is based on more stable indicators. These advantages have been described by Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman (2002). The crucial relevant caution about using parcels is that they could mask multidimensionality in an item set (Hagtvet & Nasser, 2004; Little et al., 2002). Each of the five traits has been shown to be unidimensional in independent, prior factor analyses (Cyders et al., 2007; Cyders & Smith, 2007; Smith et al., 2007; Zapolski et al., 2008), so that concern is significantly mitigated.

We therefore created four parcels of items for each trait. Each parcel score was an average of two non-adjacent items, and thus, four parcel scores were used as indicators of the latent construct representing each trait. The results we report were based on item parcels. In addition, we tested the measurement model using the 8 items as indicators of each latent variable, rather than the 4 parcels, and we report those results in an accompanying footnote. We did so to determine whether our findings would conform to what has been described by previous authors with respect to the use of many single items as latent variable indicators. Monte Carlo studies have indicated the following: First, when the sample size is large, the use of parcels versus items leads to no noticeable difference in the resulting measurement or structural solutions (Marsh, Hau, Balla, & Grayson, 1998). Second, the use of many items does not lead to decline in two absolute fit indices: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, which reflects discrepancy between the covariances implied by the model and the observed covariances per degree of freedom) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR, which reflects the average discrepancy between the correlation matrices of the observed sample and the hypothesized model). Third, even with accurate models, the use of many items leads to declines in two relative model fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI) and the nonnormed fit index (NNFI), which are based on a comparison of the chi-square value for the model with the chi-square value for a baseline model in which all variables are independent (Cook, Kallen, & Antmann, 2009; Kenny & McCoach, 2003; Marsh et al., 1998).

We treated alcohol expectancies as measured variables, not latent variables. The measure of expectancies for positive, social effects from alcohol consumption includes several different effects (active, content, friendly, fun, relaxed) that we do not view as alternative indicators of the same latent construct; rather, we view the measure as a summary term for a range of anticipated positive, social effects. The same was true for measures of each of the other expectancy domains. We measured sex and drinking behavior each with a single item, thus precluding extraction of latent variables in those two cases.

To measure model fit, we relied on the four fit indices we have described: the CFI, NNFI, RMSEA, and SRMR. Guidelines for what constitutes good fit vary, and, to date, are not adjusted for models that include many items as latent variable indicators. Typically, CFI and NNFI values above either .90 or .95 are thought to represent very good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). RMSEA values of .06 or lower are thought to indicate a close fit, .08 a fair fit, and .10 a marginal fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1999), and SRMR values of approximately .09 or lower are thought to indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). To determine good model fit, one examines fit across the four indices. In cases where most of the fit indices meet the criteria just described, the model is judged to fit well. To determine whether individual pathways were significant, we used p < .001. We used this stringent alpha level because we had a large sample and because we modeled so many covariances. Power to detect a point biserial correlation of .10, using this alpha level, was .89.

Results

Drinking Frequency Among 5th Graders and Descriptive Statistics

As Table 1 shows, 189 of the 1,843 5th graders (10.25%) reported having consumed more than just a sip or taste of alcohol. A higher frequency of boys (11.45%) than girls (8.07%) reported having consumed alcohol: although this difference did not meet the high level of statistical significance on which we relied in this large sample (p < .001), it was significant at p = .015. Consistent with past research, we found no differences in the frequency of having consumed alcohol as a function of race or ethnicity in this very young sample. A total of 111 children, or 6.1% of the sample, reported having experienced at least one problem. The most commonly reported problems were having gotten sick to the stomach or throwing up (3.6%), having gotten a hangover (2.8%), having said or done embarrassing things (2.7%), having gotten in trouble with parents for drinking (2.4%), and not being able to recall what one did while drinking (2.3%).

Table 1.

Puberty, Drinking, Problem Drinking Frequency Distribution

| Total | OnsetPuberty | DrinkerStatus | ProblemDrinking | EverDrunk | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 1843 | 483 | 189 | 111 | 60 |

| Percentage | 100 | 26.2 | 10.25 | 6.1 | 3.3 |

|

Descriptives | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (sd) | Skewness | Kurtosis | |

| Sensation Seeking | 2.63 (.71) | -.04 | -.75 |

| Negative Urgency | 2.21 (.72) | .19 | -.68 |

| Positive Urgency | 2.14 (.76) | .30 | -.67 |

| Lack of Planning | 2.01 (.56) | .57 | .29 |

| Lack of Perseverance | 2.04 (.49) | .67 | .89 |

| Positive Social | 1.52 (.34) | 1.45 | 3.53 |

| Negative Arousal | 2.60 (.62) | -.07 | -.16 |

| Sedation | 2.78 (.62) | -.24 | -.23 |

| Wild & Crazy | 2.19 (.51) | .33 | .05 |

n=1843. OnsetPuberty: pubertal onset; DrinkerStatus: ever having drank more than sip/taste; ProblemDrinking: reporting any drinking related problems; EverDrunk: lifetime status of being drunk. Positive Social, Negative Arousal, Sedation, and Wild & Crazy: expected effects of alcohol on behavior.

Concerning the typical quantity consumed, 136 children (7.4%) reported typically consuming the equivalent of one beer or one drink or less; 13 (0.7%) children reported typically drinking between two to three beers or drinks; and 8 children (0.4%) reported typically drinking four or more beers or drinks per occasion. We asked about drunkenness, and 60 children (3.3% of the sample) reported having been drunk once or twice in their lives; 3 children reported getting drunk about once a month, and 4 reported getting drunk weekly or oftener. Thus, 35.4% of the children who reported drinking reported having been drunk once or more in their lives.

Table 1 also provides descriptive statistics for the personality and alcohol expectancy measures. One variable, expectancy for positive social experiences from alcohol, had mild skew and some kurtosis; the others had trivial departures from normality. The statistical methods used in the study are robust to normality violations of this magnitude (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003).

Correlations Among Personality Traits, Alcohol Expectancies, Sex, Pubertal Status, and Drinker Status

Table 2 presents the bivariate correlations among the variables measured in the study. As the table shows, correlations among the personality traits are consistent with theory and prior research: positive and negative urgency, as facets of an overall urgency domain, are substantially correlated, as are lack of planning and lack of perseverance, which are both facets of an overall low conscientiousness domain. Otherwise, the correlations among the traits are quite modest. The alcohol expectancy scales reflecting positive, social effects and wild and crazy effects correlated with drinker status and the other two scales did not. Expectancies for positive, social effects and wild and crazy effects were very modestly related to each other. Sex is correlated with both sensation seeking and lack of planning: boys were higher on sensation seeking and failure to plan ahead than girls. Puberty is related to negative urgency, positive urgency, positive, social expectancies, wild and crazy expectancies, and drinker status: 5th graders who had experienced pubertal onset were higher on each variable. Drinker status was related to negative urgency, positive urgency, lack of planning, lack of perseverance, sensation seeking, positive, social expectancies, and wild and crazy expectancies, in addition to pubertal status, bivariately. We also examined the relationship between pubertal onset and age, which was significant (r = .17, p < .001). However, age was unrelated to all traits and did not predict drinking behavior above and beyond the effect of puberty and was not included in the model test.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations

| Pub | Sex | SS | NU | PU | PL | PS | Psocial | NA | SI | WC | Drink | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Puberty | -- | .06 | .07 | .10* | .12* | .06 | -.02 | .11* | .07* | .07* | .12* | .10* |

| Sex | -- | -.24* | .00 | -.03 | -.11* | -.05 | -.03 | -.06 | -.01 | -.14* | -.06 | |

| Sensation Seeking | -- | .27* | .32* | .13* | -.30* | .13* | .10* | .08* | .47* | .08* | ||

| Negative Urgency | -- | .63* | .36* | -.04 | .22* | .08* | .06 | .50* | .20* | |||

| Positive Urgency | -- | .31* | -.04 | .21* | .09* | .05 | .69* | .18* | ||||

| Lack of Planning | -- | .18* | .14* | .00 | -.01 | -.01 | .15* | |||||

| Lack of Perseverance | -- | .02 | -.07 | -.07 | -.20* | .10* | ||||||

| Positive Social | -- | .04 | -.08* | .17* | .20* | |||||||

| Negative Arousal | -- | .72* | .07 | -.02 | ||||||||

| Sedation | -- | .03 | -.02 | |||||||||

| Wild & Crazy | -- | .15* | ||||||||||

| Drink | -- |

n = 1,843. Pub: puberty; Sex: girls higher; SS: sensation seeking; NU: negative urgency; PU: positive urgency; PL: lack of planning; PS: lack of perseverance; PSocial: expectancy for positive social alcohol effects; NA: expectancy for negative arousal alcohol effects; SI: expectancy for sedation alcohol effects; WC: expectancy for wild and crazy behavioral effects of alcohol. Drink reflects drinker status and is dichotomous.

p < .001.

Measurement Model of the Five Traits

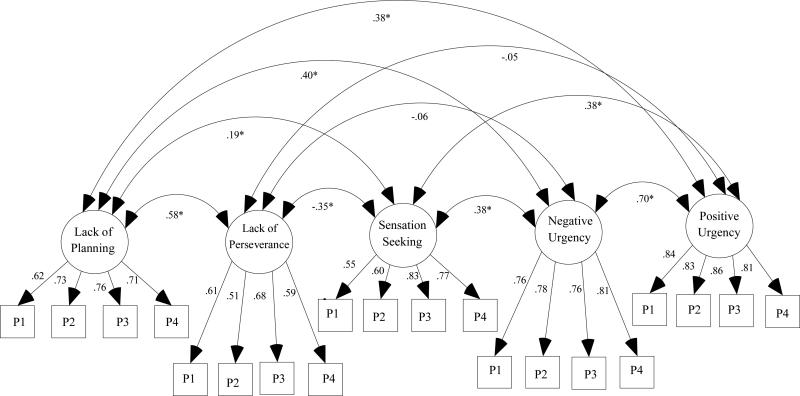

Our model for measuring the five latent variables (the five traits) fit the data well: CFI = .93; NNFI = .92, RMSEA = .06 (90% confidence interval: .05 to .06); SRMR = .07). All factor loadings were greater than .50, and 13 of 20 were greater than .70. The model, including the parcel loadings and the correlations among the latent variables, is presented in Figure 1.1

Figure 1.

Depiction of structural model of the five personality traits. Curved arrows reflect correlations among latent variables; straight arrows reflect loadings on latent variables. All factor loadings were significant at p < .001, as were associations among latent variables marked with an asterisk. For ease of presentation, error variance estimates are not presented.

Test of the Theoretical Model

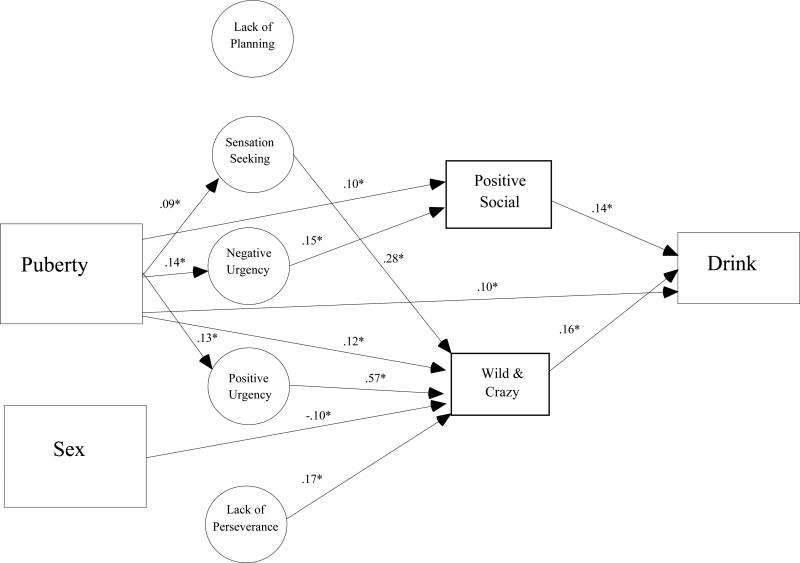

As noted above, our theoretical model had the following components and was tested as follows. First, puberty was expected to concurrently predict positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking; it was not expected to predict lack of planning and lack of perseverance (we included all five possible pathways, to test each prediction). Second, negative urgency and sensation seeking were expected to predict positive, social alcohol expectancies; and positive urgency and sensation seeking were expected to predict wild and crazy alcohol expectancies. Sex was expected to predict wild and crazy alcohol expectancies (boys higher). Neither lack of planning nor lack of perseverance was expected to predict either expectancy (we included pathways from each of the five traits and sex to both expectancies, in order to test each of these hypotheses). Third, the two expectancies were expected to predict drinker status. The bivariate correlation results were consistent with our prior expectation that alcohol expectancies for negative arousal and sedation would be unrelated to drinker status among 5th graders, and so these two expectancies were not included in the model. Fourth, we also allowed for direct prediction from pubertal status and each of the five personality traits to drinker status: doing so allowed us to detect if our hypothesized mediational pathways (described next) were partial, rather than full.

Fifth, we tested the following set of mediational pathways implied by our theory. The first set involved a hypothesized indirect effect from pubertal status on alcohol expectancies and included these tests: from puberty through negative urgency to positive, social expectancies; from puberty through positive urgency to wild and crazy expectancies; and from puberty through sensation seeking to both types of expectancies. The second set involved the acquired preparedness hypothesis that traits’ influence on drinker status is through alcohol expectancies and included these tests: from negative urgency through positive, social expectancies to drinker status; from positive urgency through wild and crazy alcohol expectancies to drinker status; and from sensation seeking through both expectancies to drinker status. We tested mediation using the indirect test provided by MPlus (Muthén & Muthén, 2004), which uses the product of the two regression coefficients method as described by MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004).

The model test included correlations among the five traits and among the two alcohol expectancy scales: it is presented in Figure 2. We do not include those cross-sectional correlations, nor do we include factor loadings, disturbance terms, or error variances in the figure, for ease of presentation. The model fit the data well: CFI = .91, NNFI = .88, RMSEA = .06 (90% confidence interval: .060 to .065), SRMR = .06. As the figure shows and consistent with our hypotheses, the experience of pubertal onset was positively related to negative urgency, positive urgency, and sensation seeking; it was unrelated to lack of planning and lack of perseverance. Negative urgency was related to expectancies for positive, social effects from drinking, but sensation seeking, though hypothesized to be, was not. As hypothesized, both positive urgency and sensation seeking were related to expectancies for wild and crazy effects from drinking, and sex predicted the wild and crazy expectancy as well (boys higher). Also as hypothesized, the two expectancies predicted drinker status.2, 3

Figure 2.

Depiction of structural model representing the theory. For ease of presentation, only hypothesized pathways, each significant at p < .001, are presented. Not included in the figure, for ease of presentation, are correlations among traits and among expectancies, disturbance terms, factor loadings, and error terms.

Results were consistent with several hypothesized mediational pathways. First, statistical findings were consistent with the hypothesis that the relationship between pubertal status and the expectancy for positive, social effects from drinking was partially mediated by negative urgency (z = 2.97, p = .001, b = .02). The evidence was consistent with partial mediation in this case, because pubertal status also had a direct effect on positive, social alcohol expectancies (b = .10, p < .001). Second, findings were consistent with the hypothesis that the relationship between pubertal status and expectancies for wild and crazy effects from drinking were mediated both by positive urgency (z = 4.92, p < .001, b = .07) and sensation seeking (z = 3.13, p < .001, b = .02).4

Results were also consistent with several hypothesized acquired preparedness effects; that is, cases in which the relationship between a trait and drinker status may have been mediated by learned expectancies. First, the relationship between negative urgency and drinker status may have been mediated by positive, social alcohol expectancies (z = 3.09, p < .001, b = .02). Second, the relationship between positive urgency and drinker status may have been mediated by expectancies for wild and crazy effects from drinking (z = 4.19, p < .001, b = .09). And third, the relationship between sensation seeking and drinker status may also have been mediated by wild and crazy alcohol expectancies (z = 3.88, p < .001, b = .04).

We had allowed for direct paths from pubertal status and each of the five personality traits to drinker status, in order to test whether the mediational pathways were consistent with full or partial mediation. Pubertal status did have a direct, non-mediated correlation with drinker status, suggesting that the mediational pathways consistent with our data did not fully explain the relationship between pubertal status and drinker status. None of the five personality traits had direct, non-mediated correlations with drinker status, suggesting that the mediational pathways could fully account for the relationship between the traits and drinker status.

To understand the magnitude of the prediction of drinker status, we computed odds ratios for each of the three significant predictors. Pubertal status had an odds ratio of 1.64 (95% confidence interval: 1.18 to 2.27): controlling for the influence of the two expectancy predictors, the odds of being in the drinker group are multiplied by 1.64 for 5th graders having experienced pubertal onset, compared to 5th graders who have not. The expectancy for positive, social effects from drinking had an odds ratio of 3.33 (95% confidence interval: 2.34 to 4.74) and the expectancy for wild and crazy effects from drinking had an odds ratio of 2.12 (95% confidence interval: 1.57 to 2.87): controlling for pubertal status and the other expectancy, each one point increase in the positive, social expectancy was associated with the odds of membership in the drinker group being multiplied by 3.33, and each one point increase in the wild and crazy expectancy was associated with the odds of membership in the drinker group being multiplied by 2.12.

Discussion

Consistent with past epidemiological work, we found evidence for alcohol consumption (more than just a sip or taste) among 5th grade children. Strikingly, of the 10.25% of 5th graders who reported consumption, 35.4% reported having been drunk at least once in their lives. These behaviors in children so young are a matter of clinical concern.

For that reason, and because of the extensive evidence showing that early onset drinking is a predictor of later substance use problems and problem drinking, it is important that we understand the correlates, and ultimately the causes, of this behavior. In this study, we tested whether cross-sectional correlations and tests of mediation were consistent with an explicit theoretical model proposing that personal characteristics of children play a role in whether they drink prior to adolescence. Each of the five sets of relationships we had proposed was observed in the current sample. Those who had experienced pubertal onset had higher levels of positive urgency, negative urgency, and sensation seeking. Our discriminant prediction was supported as well: pubertal onset was unrelated to levels of lack of planning and lack of perseverance. Three of the four hypothesized relationships between the three traits of positive urgency, negative urgency and sensation seeking and the two alcohol expectancies were observed: unexpectedly, sensation seeking was unrelated to expectancies for positive, social effects from drinking. The two expectancies each concurrently predicted drinker status, even when controlled for the other. Statistical tests of mediation were consistent with the acquired preparedness risk model: the relationship between negative urgency and drinker status was fully mediated by expectancies for positive, social effects from drinking. The relationships between positive urgency and drinker status, and between sensation seeking and drinker status, were both fully mediated by expectancies for wild and crazy effects from alcohol.

Also as anticipated, statistical tests in these cross-sectional data were consistent with the hypothesis that pubertal onset is associated with expectancy endorsement, and that its relationship with expectancy endorsement was indirect, i.e., through the three personality traits. Thus, the theory that pubertal onset leads to higher levels of emotional volatility and rash action, which in turn increase the likelihood of forming expectancies for reinforcement from drinking, was consistent with the results of this study.5

Among the predictive paths we tested, the path from positive urgency to wild and crazy alcohol expectancies was particularly strong (b = .57), and the indirect path from positive urgency through the expectancies to drinker status was quite strong (b = .09). This finding is important, because the role of positive mood-based impulsivity has not been recognized until recently (Cyders et al., 2007; Cyders & Smith, 2008) and is perhaps not fully appreciated. For these 5th graders, the tendency to act rashly when in a very good mood was very substantially related to endorsement of high-risk expectancies, and had a substantial relationship to drinker status.

Three concurrent predictions were present beyond those we hypothesized. Pubertal onset directly related to drinker status, above and beyond prediction by the personality traits and the expectancies. It is thus possible that, if puberty influences drinking behavior, it does so in ways described by the current theory (through personality trait changes and expectancy formation) and in other ways not specified by our theory as well. For example, the early onset of puberty appears to facilitate affiliation with older peers, increasing the likelihood of peer modeling of alcohol use and of peer access to alcohol (Biehl, Natsuaki, & Ge, 2007).

Puberty was also directly related to the expectancy for positive, social effects from drinking, in addition to its indirect relationship with the expectancy through personality. Lastly, lack of perseverance predicted the expectancy for wild and crazy effects from drinking. We are reluctant to generate an explanation for these unexpected findings, and we consider it important that both these effects be replicated in independent samples.

It was striking to observe that personal characteristics of children this young, including both aspects of their personalities and markers of their psychosocial learning histories, predicted whether they had consumed a drink (or more) of alcohol. The variability in whether 5th grade children drink alcohol appears not to be just a function of context and access, but rather to be a function, in part, of the children themselves. That high-risk traits and high-risk learning are associated with drinker status in 5th graders suggests the possibility that early drinking is, itself, a function of other risk factors. Should this cross-sectional finding be confirmed with longitudinal data, there will be good reason to intervene very early to address these risk factors.

Although the theory driving this research is causal in nature, the present study did not test the causal hypotheses. These cross-sectional findings should be understood to be consistent with our theory, but not to be definitive support for it. The fact that these data were consistent with the theory indicates that the theory remains viable and suggests the value of putting the model to more stringent, longitudinal tests.

The cross-sectional nature of the design is the most serious limitation of the study. We used a lifetime measure of alcohol use, and we cannot know whether alcohol use occurred prior to pubertal onset. Nevertheless, there are sound theoretical reasons for proposing the order of variables that we did. It is much more likely that change in pubertal status precedes change in personality than the other way around. As noted above, prior longitudinal research shows that personality predicts subsequent changes in expectancies (Settles et al., in press); it thus seems likely that changes in personality precede changes in alcohol expectancies. Finally, expectancies have been shown numerous times to predict the subsequent onset of drinking (drinking experience then does predict subsequent changes in expectancies), and experimental manipulations of expectancies influence drinking behavior, so there was good reason to place expectancies prior to drinking in our model (Darkes & Goldman, 1993; Ouellette et al., 1999; Smith, 1994; Smith, Goldman, Greenbaum, & Christiansen, 1995).

Other limitations of this study should be noted. Our model holds that pubertal onset leads to increases in the urgency traits and sensation seeking as a developmentally limited experience of adolescence. But because the study was a cross-sectional assessment of children who were, for the most part, 11 years old, we cannot determine whether the effects we observed were due specifically to early pubertal onset. An alternative to our model is that early puberty leads to increases in the traits and the more common, slightly later pubertal onset does not. If that model is correct, the trait component of the risk process may be relevant only for those who experience early puberty. Although we believe there are sound empirical and theoretical reasons for our formulation, it is of course true that longitudinal data will be necessary to compare these two, competing explanations.

We assessed each attribute by questionnaire. Interview assessments might have provided the opportunity for clarification of questions and might have led to increased precision; however, it may also be true that children this young would prove reluctant to admit to their drinking behavior, and perhaps even their alcohol expectancies, in an interview with an adult. We did not assess the drinking context of the children, nor did we assess other important risk factors, such as parental or peer drinking. As a result, we know very little about the nature of these early drinking experiences, and we do not know how other risk factors relate to those studied here. Lastly, it is of course likely that some 5th grade consumption reflects an isolated episode or experimental use that will prove unrelated to future alcohol use problems.

Despite these limitations, this study offers important advances to the effort to understand very early drinking. The results provide evidence that it is possible to investigate the correlates, and perhaps also the causes, of pre-adolescent consumption. There is merit to investigating whether personal characteristics of children, and not just their contexts, play a role in the risk process. On a more specific level, the findings support a risk model that integrates personality changes as a function of puberty with the acquired preparedness model of risk. It is possible that pubertal changes in emotion-driven rash action, and in sensation seeking, lead to high-risk learning and an increased likelihood of very early consumption. If this conclusion is supported by longitudinal data, clinical scientists will be in a position to develop newly specific preventive interventions for very young children.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were supported by NIAAA award RO1 AA 016166 to Gregory Smith.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb

The measurement model using the 8 items as indicators, rather than the 4 parcels, resulted in these fit index values: CFI = .85, NNFI = .84, RMSEA = .06 (90% confidence interval .058 to .061), and SRMR = .07. Just as was true for parcels as latent variable indicators, all factor loadings were significantly greater than zero at p < .001, and median loadings were: lack of planning (.55), negative urgency (.68), sensation seeking (.56), lack of perseverance (.50), and positive urgency (.73). Thus, consistent with Monte Carlo research, the substantive results of the model test did not differ meaningfully when using parcels or items, the two absolute fit indices reported the same quality of fit with the item-level model as with the parcel-level model, and the two relative fit indices produced lower values. This set of findings does not indicate a problem with model fit (Kenny & McCoach, 2003).

In order to determine whether there was significant covariance among the study variables due to participants attending the same school, we calculated intraclass coefficients for each of our major model components (using school membership, n = 23, as the nesting variable). The largest intraclass coefficient was .03 for negative urgency; all other values ranged from .02 to .00. These low values indicate that very little or no shared variance among study variables was due to attending the same school. In preliminary analyses, we also tested whether sex or race moderated any of the predictive relationships we tested. They did not.

We also tested the full, structural model using items instead of parcels as latent variable indicators. The results of that test precisely paralleled those of the measurement model: precisely the same effects were statistically significant, they differed little in magnitude (the largest difference was two-hundredths in the path coefficient: for example, the path from negative urgency to positive social expectancies was .15 in the model presented in the text and .17 in the model using item indicators), the absolute fit indices reflected the same level of model fit (RMSEA = .06, 90% confidence interval .060 to .063; SRMR = .08), and the two relative fit indices were lower (CFI = .82; NNFI = .80).

There is clear evidence that early puberty is associated with increased drinking behavior over the following several years (Costello, Sung, Worthman, & Angold, 2007; Westling et al., 2008). The current study cannot separate influences of pubertal status in general from influences of early puberty on personality and the risk model we describe. In the current sample of 5th graders, 26.2% reported having gone through puberty. Normatively, these children went through puberty before most of their peers, so the association between pubertal status and drinking in this study could reflect the operation of factors associated with early puberty.

Of course, as was true of the children in the current study, most youth do not engage in problem behaviors with the onset of puberty. The many positive aspects of childhood and adolescent development, including parental involvement, positive peer influence, and humans’ self-determination to pursue adaptive goals (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Padilla-Walker & Bean, 2009; Santor & Youniss, 2002), all contribute to the remarkable success with which children navigate this important developmental period.

References

- Allen MT, Matthews KA. Hemodynamic responses to laboratory stressors in children and adolescents: The influences of age, race, and gender. Psychophysiology. 1997;34:329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KG, Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Fischer SM, Fister S, Grodin D, Boerner LM, Hill KK. Elementary school drinking: The role of temperament and learning. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:21–27. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biehl MC, Natsuaki MN, Ge X. The influence of pubertal timing on alcohol use and heavy drinking trajectories. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:153–167. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen K. Latent variables in psychology and the social sciences. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:605–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolles RC. Reinforcement, expectancy and learning. Psychological Review. 1972;79:394–409. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D, Mellenbergh GJ, Van-Heerden J. The theoretical status of latent variables. Psychological Review. 2003;110:203–219. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.110.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Rosso J, Gargiulo J. Validity of self-report measures of girls’ pubertal status. Child Development. 1987;58:829–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West S, Aiken L. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd Ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman L, Coleman J. The measurement of puberty: a review. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:535–550. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D. Having a fit: impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT's unidimensionality assumption. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18:447–460. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9464-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbert KM, Burt SA, McGue M, Iacono WG, Klump KL. Puberty and the genetic diathesis of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:788–796. doi: 10.1037/a0017207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. The role of personality dispositions to risky behavior in predicting first year college drinking.. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Baltimore, Maryland. Jul, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Flory K, Rainer S, Smith GT. Prospective study of the integration of mood and impulsivity to predict increases in maladaptive action during the first year of college. Addiction. 2009;104:193–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Mood-based rash action and its components: Positive and negative urgency. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43:839–850. [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT. Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: The trait of urgency. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:807–828. doi: 10.1037/a0013341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: Experimental evidence for a mediational process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:344–353. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.2.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darkes J, Goldman MS. Expectancy challenge and drinking reduction: Process and structure in the alcohol expectancy network. Experimental & Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1998;6:64–76. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.6.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:227–268. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: A risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:745–750. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Really underage drinkers: The epidemiology of children's alcohol use in the United States. Prevention Science. 2007;8:192–205. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0072-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Molina BSG. Children's introduction to alcohol use: Sips and tastes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32:108–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Goldman MS. Empirical modeling of an alcohol expectancy memory network in elementary school children as a function of grade. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;4:209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn ME, Goldman MS. Age and drinking-related differences in the memory organization of alcohol expectancies in 3id, 6th, and 12th grade children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:579–585. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor Analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:286–299. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg JH, Halpern-Felsher BL, Millstein SG. Beyond invulnerability: The importance of benefits in adolescents’ decision to drink alcohol. Health Psychology. 2002;21:477–484. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSMIV alcohol abuse and dependence: Results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenlund K, Johnson C, Webber L, et al. Cigarette smoking attitudes and first use among third-through sixth-grade students: The Bogalusa Heart Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1345–1348. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.8.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagtvet KA, Nasser FM. How well do item parcels represent conceptually defined latent constructs? A two-facet approach. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:168–193. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C. Initial and experimental stages of tobacco and alcohol use during late childhood: Relation to peer, parent, and personal risk factors. Addictive Behaviors. 1997;22:685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahoda G, Cramond J. Children and alcohol: A developmental study in Glasgow. Her Majesty's Stationery Office; London: 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BT, Corbin W, Fromme K. A review of expectancy theory and alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2001;96:57–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, McCoach DB. Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2003;10(3):333–351. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E, Bates ME, Pandina RJ. Age of first use: Its reliability and predictive utility. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:638–643. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Richards MH. Family emotions: Do young adolescents and their parents experience the same states? Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:567–583. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widamon KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Luna B, Sweeney JA. The emergence of collaborative brain function: fMRI studies of the development of response inhibition. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021:296–309. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman West, Sheets A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Hurrelmann K. Health impairments in adolescence: The biopsychosocial “costs” of modern life-style. Walter De Gruyter; Oxford, England: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau K, Balla JB, Grayson D. Is more ever too much? The numbers of indicators per factor in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1998;33(2):181–220. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3302_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J, Flory K, Lynam D, Leukefeld C. A test of the four-factor model of impulsivity-related traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34:1403–1418. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus: User's Guide. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellette JA, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M. Parents, peers, prototype: Antecedents of adolescent alcohol expectancies, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related life problems in rural youth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Bean RA. Negative and positive peer influence: Relations to positive and negative behaviors for African American, European American, and Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santor CE, Youniss J. The relationship between positive parental involvement and identity achievement during adolescence. Adolescence. 2002;37:221–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles RF, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Longitudinal validation of the acquired preparedness model of drinking risk. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0017631. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT. Psychological expectancy theory and the identification of high risk adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Anderson KG. Adolescent risk for alcohol problems as acquired preparedness: A model and suggestions for intervention. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O'Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, Alcohol, and Substance Abuse: Reaching Teens Through Brief Interventions. Guilford Press; New York: 2001. pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Fischer S, Cyders MA, Annus AM, Spillane NS, McCarthy DM. On the validity and utility of discriminating among impulsivity-like traits. Assessment. 2007;14:155–170. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Goldman MS, Greenbaum P, Christiansen BA. The expectancy for social facilitation from drinking: the divergent paths of high-expectancy and low-expectancy adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:32–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, McCarthy DM, Goldman MS. Self-reported drinking and alcohol-related problems among early adolescents: Dimensionality and validity over 24 months. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;56:383–394. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Behavioral Reviews. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: What changes, and why? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021:51–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman EG. Purposive behavior in animals and men. Century Company; New York: 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Westling E, Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Peterson M. Pubertal timing and substance use: The effects of gender, parental monitoring and deviant peers. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Spear LP, Fuligni AJ, Angold A, Brown JD, Pine D, Smith GT, Giedd J, Dahl RE. Transitions Into Underage and Problem Drinking: Developmental Processes and Mechanisms Between 10 and 15 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S273–S289. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The disaggregation of impulsivity in children.. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism; Washington, D. C.. Jul, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TCB, Stairs AM, Settles RF, Combs JL, Smith GT. The measurement of dispositions to rash action in children. Assessment. doi: 10.1177/1073191109351372. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Donovan JE, Masten AS, Mattson ME, Moss HB. Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics. 2008;121:S252–272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]