Abstract

Objectives

To summarise existing evidence on a target oriented approach for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search including all clinical trials testing clinical, functional, or structural values of a targeted treatment approach. Our search covered Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases until December 2008 and also conference abstracts (2007, 2008).

Results

The primary search yielded 5881 citations; after the selection process, 76 papers underwent detailed review. Of these, only seven strategic clinical trials were extracted: four studies randomised patients to routine or targeted treatment, two compared two different randomised targets and one compared targeted treatment to a historical control group. Five trials dealt with early RA patients. All identified studies showed significantly better clinical outcomes of targeted approaches than routine approaches. Disability was reported in two studies with no difference between groups. Four studies compared radiographic outcomes, two showing significant benefit of the targeted approach.

Conclusion

Only few studies employed randomised controlled settings to test the value of treatment to a specific target. However, they provided unanimous evidence for benefits of targeted approaches. Nevertheless, more data on radiographic and functional outcomes and on patients with established RA are needed.

Introduction

Many new treatment options make unprecedented outcomes achievable in rheumatoid arthritis (RA).1 2 In parallel, insights on the importance of early effective therapy3 4 and implications of disease activity on function5 6 and joint damage6–8 led to paradigmatic changes in therapeutic approaches, such as frequent evaluations of disease activity to allow for timely changes of therapies.9–13 Additionally, validated composite disease activity measures have made disease activity assessment easy.14 15 Nevertheless, heterogeneity of therapeutic aims and patient expectations16 characterise daily practice of RA treatment.17 All this suggests a need to provide rheumatologists and patients with pertinent information on therapeutic targets and means to achieve them.18 19

Strict definitions of treatment targets intend to facilitate strategic acting in routine care and require physicians and patients to discuss and adopt therapeutic changes within distinct time frames, ideally following therapeutic algorithms. This approach has been utilised in many diseases, like diabetes,20 21 hypertension22–24 or hyperlipidaemia.25 However, this policy needs to be evidence based to the best possible extent.

Here we report on a systematic review of available evidence regarding the effects of treating RA strategically according to defined outcome targets.

Methods

Shaping the systematic literature review

As a first step, the international steering committee of the Treat-To-Target (T2T) project, comprising a group of expert rheumatologists and a patient (MdW), designed a literature search that aimed at ‘treating to target’-strategy trials in RA. The search was then performed by a project fellow (MS), a control search by a second fellow (RK) and by two mentors (DA, DvdH).

The following definitions were made: (1) strategy trial – clinical trial of any RA drug treatment, in which a clear outcome target was the primary end point and therapeutic consequences of failing to reach the target were predefined; (2) targets – a target could be formulated by clinical, serological, patient-reported, functional, or radiographic variables; individual measures (eg, joint counts or acute phase reactants), composite scores (eg, disease activity score or simplified disease activity index), or response criteria (eg, those defined by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or the European League Against Rheumatism) were considered alike; (3) outcomes – Clinical, functional, serological and/or radiographic changes, as defined in the respective trials, were compared between treatment groups.

Implementation of the systematic literature review

We searched Medline, Embase and Cochrane databases from their inception until December 2008. Additionally, ACR and European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) abstracts of 2007 and 2008 were screened. The search was limited to humans, adults and the English language. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria and the list of search strings are shown in supplementary tables (tables S1 and S2). We did not exclude studies based on quality.

From the identified strategy trials, data were extracted concerning definitions of targets and success rates of applied strategies.

Results

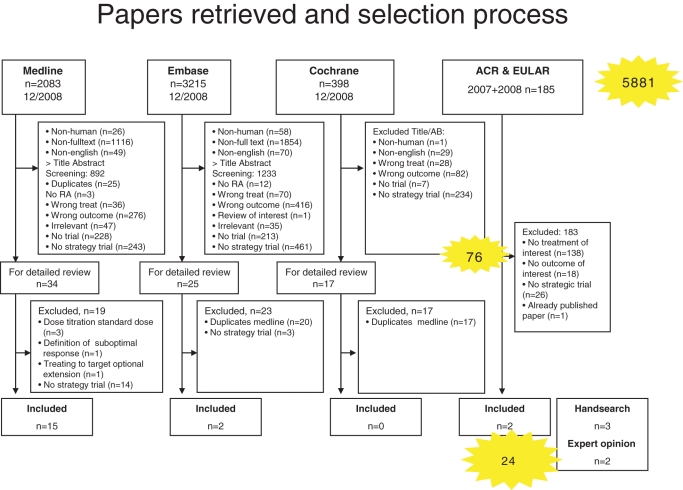

We retrieved 5881 citations for further evaluation (figure 1). Title and abstract screening according to our selection criteria (supplementary table S1) left 76 papers for detailed review. Among those, 17 trials published in full and 2 abstracts addressed direct assessment of treating to target. By hand search of references, we identified three additional papers; further, one full paper and one abstract were included based on expert opinion. This gave a total of 24 publications for this review (figure 1), of which only 7 were strategic trials: 4 trials randomised patients to routine or targeted treatment,26–29 two compared different randomised targets30 31 and one compared targeted treatment to historical control.32

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic literature search. Illustrated are the results of the initial search and the selection process of abstract screening, full text review and hand search. AB, abstract; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Randomised strategic trials comparing targeted versus routine care

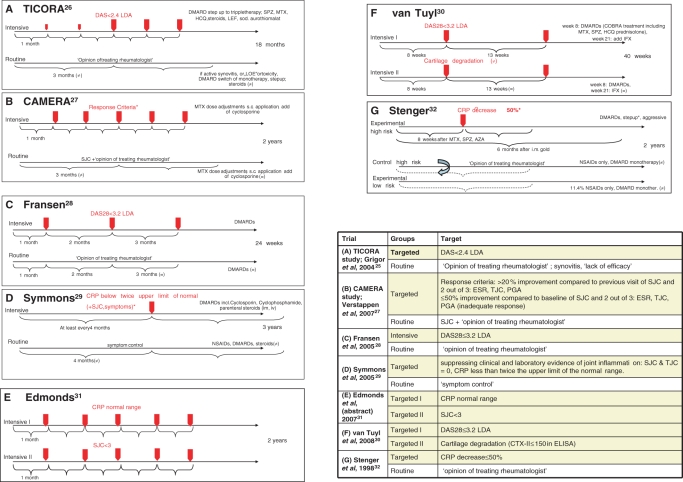

Only four trials had randomised patients to a targeted treatment algorithm versus routine care. In Tight Control of Rheumatoid Arthritis (TICORA),26 treatment of early RA aimed at low disease activity (LDA) by Disease Activity Score (DAS), comparing DAS-driven treatment adaptations upon monthly assessments with 3-monthly routine care. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA)27 aimed at remission of early RA, comparing monthly treatment adaptation by computerised decision if >20% (50%) reduction of several variables was not attained with 3-monthly routine care. A cluster randomised trial by Fransen et al 28 compared the proportion of patients reaching LDA at the end of follow-up and the number of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) changes during 24 weeks (co-primary end points) in outpatient centres using systematic, DAS28-steered treatment protocols with centres providing routine care. The treatment decision in the DAS28-driven group depended on a threshold of 3.2, indicating LDA. Finally, Symmons et al29 tested the effect of aggressive versus symptomatic therapy on physical outcome (Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)) in established RA. Decisions for treatment adaption were driven by joint count- and C reactive protein (CRP) thresholds. Designs of these trials are depicted in figure 2; baseline characteristics are tabulated in supplementary table S3.

Figure 2.

Design of the seven core clinical trials. (A) TICORA study (Grigor et al 2004)26; (B) CAMERA study (Verstappen et al 2007)27; (C) Fransen et al 200528; (D) Symmons et al 200529; (E) Edmonds et al 2007 (abstract)31; (F) van Tuyl et al 200830; and (G) Stenger et al 1998.32 Intensive and routine treatment arms are displayed, red arrows mark the scheduled intervals for target assessment. Table 1 specifies the targets of trials A–G. AZA, Azathioprine; CAMERA, Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS, Disease Activity Score; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IFX, ifosfamide; LDA, low disease activity; LEF, leflunomide; MTX, methotrexate; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; sc, subcutaneous; SJC, swollen joint count; sod., sodium; SPZ, sulfinpyrazone; TICORA, tight control of rheumatoid arthritis.

Characteristics of the core trials, including treatment targets and visit intervals, as well as clinical, functional and radiographic outcomes are summarised in table 1 and will be detailed below.

Table 1.

Targets and visit intervals (left columns) and clinical, functional and structural outcomes (right columns) of core trials

| Group | Treatment-decision driving target | Interval of controls | N | Outcomes/final treatment target p Values indicate differences of outcomes between the targeted (T) and the routine group (R) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) TICORA26 | ||||

| Targeted group (T) | DAS<2.4 LDA | 1 Month | 55 |

|

| Routine control group (R) | Opinion of treating rheumatologist | 1 Month | 55 | |

| (B) CAMERA27 | ||||

| Targeted group (T) | Improvement of number of swollen joints: >20% compared to previous visit/50% compared to baseline Improvement in 2 out of 3 criteria: ESR, TJC, PGA >20% compared to previous visit | 1 Month | 151 |

|

| Routine control group (R) | Decrease of SJC, if number of SJ unchanged, assessors' judgement, looking at TJC, ESR, PGA | 3 Months | 148 | |

| (C) Fransen et al28 | ||||

| Targeted group (T) | DAS28<3.2 LDA | 1 Month starting, then 2 months, then 3 months (both groups) | 205 |

|

| Routine control group (R) | Opinion of treating rheumatologist | 179 | ||

| (D) Symmons et al29 | ||||

| Targeted group (T) | CRP<twice the upper limit of normal range TJC=0 and SJC=0 Symptom control | At least every 4 months (both groups) | 233 |

|

| Routine control group (R) | Symptom control | 233 | ||

| (E) Edmonds et al31 (abstract) | ||||

| Targeted group I | CRP normal range | 1 Month (both groups) | 82 |

|

| Targeted group II | SJC <3 | 85 | ||

| Routine control group | – | 82 | ||

| (F) van Tuyl et al30 | ||||

| Targeted group I | DAS28<3.2 LDA | 8 Weeks, then 13 weeks (both groups) | 11 |

|

| Targeted group II | Cartilage degradation: CTX-II excretion ≤150 nmol/mmol creatinine | 10 | ||

| (G) Stenger et al32 | ||||

| Targeted group (T) | CRP decrease >50% | 8 Weeks (both groups) | 139 | |

| Routine control group (R) | Opinion of treating rheumatologist | 89 | ||

OR (95% CI);

outcome at 1 year;

outcome at 2 years.

AUC, area under the curve; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CAMERA, Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis; CRP, C reactive protein; CTX-II, C-terminal cross-linking of type II collagen; DAS, Disease Activity Score; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; EGA, evaluator global assessment; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; JSN, joint space narrowing; LDA, low disease activity; NR, not reported; OSRA, overall status in rheumatoid arthritis; PGA, physician's global assessment; SJC, swollen joint count; TICORA, tight control of rheumatoid arthritis; TJC, total joint count; TSS, total Sharp score.

Significantly greater DAS reduction and higher likeliness to achieve remission following intensive disease management was evident in all four trials. In TICORA,26 the primary end point, EULAR good response, as well as DAS remission were significantly more frequent upon intensive than routine care. CAMERA27 showed significant benefits of targeted treatment regarding its primary end point, remission for 3 months. Fransen et al28 showed that both the proportion of patients reaching LDA and frequency of DMARD changes during follow-up favoured a DAS28-driven DMARD strategy. Symmons et al29 found significant differences in clinical outcomes in the evaluator global assessment, while other measures, including joint counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and patient global visual analogue scale, were not significantly different.

Physical function was the primary outcome in the trial by Symmons et al29; the intensive group failed to show significant differences compared to routine care regarding HAQ changes. Also CAMERA27 did not show significant differences in functional outcomes.

Grigor et al26 reported significantly less progression of radiographic changes26 in the intensive treatment group. In contrast, no significant differences in annual radiographic progression were described in the CAMERA study.27 Two of the studies did not report radiographic data28 29 (table 1, figure 2).

Randomised strategic trials comparing two targeted strategies

van Tuyl et al30 presented a study protocol randomising early RA patients to different targeted and tight monitoring schedules: one group aiming at DAS28 remission, the other at suppressing cartilage degradation as assessed by measuring urinary C-terminal cross-linking of type II collagen. Results did not differ significantly between the two groups with similar overall remission rates in both arms (figure 2, table 1). However, as the authors concede, this was a very small pilot study. Similarly, Edmonds et al31 reported in abstract form on steering at normal CRP levels versus a joint count targeted approach. Their results suggested that targeting CRP provides better interference with radiographic damage (table 1, figure 2).

Non-randomised cohort studies comparing two targeted strategies

Stenger et al32 compared an aggressive treatment protocol that stipulated change of DMARD therapy if after 8 weeks CRP decrease was less than 50% in patients with a high risk of developing aggressive disease; the comparator arm on regular therapy was a retrospectively assessed group of high risk patients. After 2 years, the area under the curve for CRP was significantly lower in the intensive treatment group than in the historic control. While no functional data were provided, the reported radiographic progression favoured the intensive treatment (table 1).

Additional studies

A number of studies used the treat to target concept, but, in contrast to the mentioned papers, did not have a non-targeted control arm, since all arms pursued the same target with different treatment sequences (supplementary table S4). Likewise, several trials compared step-up with combination regimes, dose titration of agents or different therapies to reach a defined target without directly addressing the efficacy of treating to target. A description of these studies can be found in the supplementary material accompanying this manuscript.

Discussion

Our review revealed that only few controlled studies investigated the value of strategic treatment schedules. Importantly, study designs and evaluated targets were very heterogeneous; for example, the Edmonds and van Tuyl studies are inherently different in design as compared to the others in that their approach compares two T2T approaches while the others compare a T2T approach with the routine approach. Nevertheless, all studies investigating early disease showed significantly better clinical outcomes of the targeted approach. Functional outcomes, reported in two trials, failed to show significant gains.27 29 Four studies compared radiographic outcomes,26 27 29 32 of which two showed a significant benefit of the targeted therapy.26

Five26–28 30 32 studies investigated early disease (using different definitions of ‘early’ – see supplementary table S3). Only one trial29 focused explicitly on late disease (duration: >5 years) and found no advantage of tight control on functional outcomes. Thus, patients with established RA seem to be underinvestigated regarding the value of treating to a target. Since longer disease duration impairs treatment outcomes,33 extending results from early RA to the general patient population could be misleading. Furthermore, just focusing on HAQ might also be misguiding, since with increasing disease duration responsiveness of physical function to therapeutic interventions decreases (even to placebo levels).34

Utilised targets showed considerable heterogeneity (table 1, figure 2). Among the randomised trials comparing targeted versus routine approaches, three out of four employed state targets,26 28 29 an approach that has been favoured as being more appropriate than assessing changes from baseline.35 Only in CAMERA,27 the target was formulated as reaching defined improvement criteria. Also, visit intervals were noticeably heterogenous: clinical assessments were performed from monthly26–28 31 to every 429 36 months. Two trials randomised patients to different visit intervals.26 37 In both, patients assigned to intensive strategy were seen monthly, those in routine care every 3 months.

In conclusion, only few studies have used a randomised approach to test the value of treatment to a specific target. However, all of them provided compelling evidence of clinical benefits of such an approach. However, more data are needed concerning radiographic and functional outcomes and patients with longstanding RA have not been sufficiently investigated.

Footnotes

Competing interests This study was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Immunology. Abbott had no influence on the selection of papers, extraction of data or writing of this manuscript. Francis Berenbaum was the Handling Editor.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, et al. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2007;370:1861–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet 2008;372:375–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Combe B, Landewe R, Lukas C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of early arthritis: report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Heide A, Remme CA, Hofman DM, et al. Prediction of progression of radiologic damage in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1466–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drossaers-Bakker KW, de Buck M, Van Zeben D, et al. Long term course and outcome of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis. The effect of disease activity and radiologic damage over time. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1854–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Courvoisier N, Dougados M, Cantagrel A, et al. Prognostic factors of 10-year radiographic outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2008;10:R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syversen SW, Gaarder PI, Goll GL, et al. High anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide levels and an algorithm of four variables predict radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a 10-year longitudinal study. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:212–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plant MJ, Williams AL, O'Sullivan MM, et al. Relationship between time-integrated C-reactive protein levels and radiologic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1473–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fiehn C, Jacki S, Heilig B, et al. Eight versus 16-week re-evaluation period in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with leflunomide or methotrexate accompanied by moderate dose prednisone. Rheumatol Int 2007;27:975–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aletaha D, Funovits J, Keystone EC, et al. Disease activity early in the course of treatment predicts response to therapy after one year in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3226–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breedveld FC, Kalden JR. Appropriate and effective management of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:627–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolen JS, Sokka T, Pincus T, et al. A proposed treatment algorithm for rheumatoid arthritis: aggressive therapy, methotrexate and quantitative measures. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003;21(5 Suppl 31):S209–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Combe B. Early rheumatoid arthritis: strategies for prevention and management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:27–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Remission of rheumatoid arthritis: should we care about definitions? Clin Exp Rheumatol 2006;24 6(Suppl 43):S–45–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aletaha D, Stamm T, Smolen J. Measuring disease activity for rheumatoid arthritis. Z Rheumatol 2006;65:93–6, 98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heller JE, Shadick NA. Outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: incorporating the patient perspective. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2007;19:101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoels M, Aletaha D, Smolen JS, et al. Follow-up standards and treatment targets in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): results of a questionnaire at the EULAR 2008. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69;575–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther 2005;7:R796–806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:244–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bray K, Turpin RS, Jungkind K, et al. Defining success in diabetes disease management: digging deeper in the data. Dis Manag 2008;11:119–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moses RG. Achieving glycosylated hemoglobin targets using the combination of repaglinide and metformin in type 2 diabetes: a reanalysis of earlier data in terms of current targets. Clin Ther 2008;30:552–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verdecchia P, Staessen JA, Angeli F, et al. Usual versus tight control of systolic blood pressure in non-diabetic patients with hypertension (Cardio-Sis): an open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2009;374:525–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arguedas JA, Perez MI, Wright JM. Treatment blood pressure targets for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD004349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ogihara T, Nakao K, Fukui T, et al. The optimal target blood pressure for antihypertensive treatment in Japanese elderly patients with high-risk hypertension: a subanalysis of the candesartan antihypertensive survival evaluation in Japan (CASE-J) trial. Hypertens Res 2008;31:1595–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milionis HJ, Rizos E, Kostapanos M, et al. Treating to target patients with primary hyperlipidaemia: comparison of the effects of ATOrvastatin and ROSuvastatin (the ATOROS study). Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1123–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ, et al. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1443–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fransen J, Bernelot Moens H, Speyer I, et al. Effectiveness of systematic monitoring of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity in daily practice: a multicentre, cluster randomised control trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1294–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Symmons D, Tricker K, Roberts C, et al. The British Rheumatoid Outcome Study Group (BROSG) randomised controlled trial to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of aggressive versus symptomatic therapy in established rheumatoid arthritis. Health Technol Assess 2005;9:iii–iv, ix–x, 1–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Tuyl LH, Lems WF, Voskuyl AE, et al. Tight control and intensified COBRA combination treatment in early rheumatoid arthritis: 90% remission in a pilot trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1574–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Edmonds J, Lassere M, Sharp JT, et al. Objectives study in RA (OSRA): a RCT defining the best clinical target for disease activity control in RA. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(Suppl II):32517012290 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stenger AA, Van Leeuwen MA, Houtman PM, et al. Early effective suppression of inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis reduces radiographic progression. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:1157–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson JJ, Wells G, Verhoeven AC, et al. Factors predicting response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of disease duration. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:22–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aletaha D, Strand V, Smolen JS, et al. Treatment-related improvement in physical function varies with duration of rheumatoid arthritis: a pooled analysis of clinical trial results. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:238–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aletaha D, Funovits J, Smolen JS. The importance of reporting disease activity states in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2622–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verschueren P, Esselens G, Westhovens R. Daily practice effectiveness of a step-down treatment in comparison with a tight step-up for early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bakker MF, Jacobs JW, Verstappen SM, et al. Tight control in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: efficacy and feasibility. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66 (Suppl 3):iii56–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]