Abstract

Background

Self-report measures of medication adherence are inexpensive and minimally intrusive. However, the validity of self-reported adherence is compromised by recall errors for missed doses and socially desirable responding.

Method

Examined the convergent validity of two self-report adherence measures administered by computerized interview: (a) recall of missed doses and (b) a single item visual analogue rating scale (VAS). Adherence was also monitored using unannounced phone-based pill counts which served as an objective benchmark.

Results

The VAS obtained adherence estimates that paralleled unannounced pill counts. In contrast, self-reported recall of missed medications consistently over-estimated adherence. Correlations with participant characteristics also suggested that the computer administered VAS was less influenced by response biases than self-reported recall of missed medication doses.

Conclusions

A single item VAS offers an inexpensive and valid method of assessing medication adherence that may be useful in clinical as well as research settings.

Monitoring medication adherence poses multiple challenges in clinical and research settings. Several strategies are available for measuring medication adherence, each with their own relative advantages and disadvantages. Table 1 presents the most common methods used for assessing medication adherence in research and clinical practice. While electronic medication monitoring systems offer considerable measurement precision, they are costly and can interfere with commonly used adherence improvement strategies, particularly pill boxes and pocketed dose containers [1, 2]. Alternatively, unannounced pill counts provide accurate information about medications adherence [3–5]. Once again, however, accurate estimates of adherence come at a cost, and unannounced pill counts require significant staff time and patient burden.

Table 1.

Summary of advantages and disadvantages for commonly used measures of medication adherence.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Measures | ||

| MEMs caps | Accurate, objective, provides continuous data | Assesses one drug, prohibits use of pillboxes for one drug, can be lost, malfunction, can result in over and under reporting, self-monitoring effects |

| Office-based pill counts | Accurate, objective, long interval, low-burden, low cost | Potential bias from not having all pills at time of count, pill dumping |

| Unannounced home-based pill counts | Accurate, objective, assures all pills counted, long interval, limits pill dumping, includes pocketed doses | Cost, intrusive, potential Hawthorne effect, high staff burden |

| Unannounced phone-based pill counts | Accurate, objective, assures all pills counted, long interval, limits pill dumping, includes pocketed doses | Intrusive, potential Hawthorne effect, high staff burden |

| Blood/hair concentrations | Accurate, objective, closely tied to doses taken | Cost, difficult to achieve in community vs clinical settings |

| Pharmacy records | Objective, low burden | Intrusive, high staff demand |

| Self-report measures | ||

| Self-report recall missed doses | Low-cost, low burden, correlates with MEMs caps, pill counts, and viral load | Assesses adherence over brief time, potential over-estimate of adherence, relies on memory, possible social desirability bias |

| Visual Analogue Scale | Single item, easy to administer, correlates with electronic medication monitoring | Relies on memory, possible social desirability bias |

| Medication diaries | Provide continuous data, can be linked to contextual factors social desirability bias Difficult in community settings | High burden, potential self-monitoring reactivity, potential |

In contrast to objective measures of medication adherence, self-report assessments are inexpensive and carry minimal patient burden. State of the science reviews have concluded that self-reported adherence assessments correlate with objective measures including electronic monitoring systems and self-report methods are associated with health indicators, most critically HIV viral load [6]. The most widely used self-report adherence measure was developed by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) network [7, 8]. The ACTG interview asks patients to recall how many doses of their medications they missed in the past week using day-by-day retrospective recall. Self-reported recall of medications missed (SR-recall) is easily integrated into clinical interviews and is relatively non-intrusive. However, self-report adherence measures rely on memory and tend to over-estimate adherence [9]. Asking individuals to recall an event in which they forgot to take their medications has obvious cognitive limitations and can be influenced by socially desirable responding because people with HIV are told routinely to never miss a dose of their medications.

An alternative and even less burdensome self-report adherence measure that has demonstrated promising results is a single item visual analogue rating scale (VAS). The VAS asks individuals to consider a specified time period, such as the previous month, and estimate along a continuum the percentage of medication doses (0% to 100%) that they had taken as prescribed [10, 11]. The VAS correlates in the moderate to high range with both unannounced pill counts and SR-recall [10, 11]. The VAS also significantly correlates with HIV viral load suppression, the endpoint of successful HIV treatment adherence [10–12]. A simple single item measure of adherence is obviously appealing particularly when considered next to the more expensive and burdensome alternatives to measuring medication adherence. The ease of administration offered by the VAS also makes it an attractive measure for clinical settings [13]. Unfortunately, not all studies have reported positive findings from the VAS, with some failing to demonstrate significant associations between the VAS and objective measures of adherence [14, 15].

Another aspect of self-report adherence is the administration procedures. For example, SR-recall measures are increasingly conducted using computerized interviews. Computer administration offers several advantages over face-to-face interviews, including maintaining standardized procedures and automated data collection. Perhaps most attractive is that computers do not send subtle verbal and nonverbal response cues that can influence socially desirable responding during face-to-face interviews [16, 17]. The VAS has been computer administered in research and clinical settings [18]. However, most validity studies of the VAS have used interpersonal interview administration that may have yielded over-estimates of adherence.

The current study was conducted to examine a computerized administration of VAS adherence assessment in relation to SR-recall adherence and an objective measure of medication adherence, specifically unannounced pill counts. In an attempt to minimize socially desirable responding, we administered the VAS and ACTG SR-recall adherence assessments using an audio-computer assisted interview (ACASI). Computerized interviews demonstrate validity for measuring behaviors that are sensitive to socially desirable responding, such as substance use and sexual behaviors [16]. In addition, computerized administration of self-reported adherence measures allow for medication-by-medication assessments that can be averaged across drugs within a regimen. In one study that used computerized administration of the VAS, adherence rates corresponded to the ACTG SR-recall (r = .58) [19]; adherence estimates were higher on the VAS in comparison to SR-recall, the opposite pattern of what is observed in interpersonal interview administration. The aims of our study were therefore to examine the validity and accuracy of a computer administered VAS for assessing self-reported medication adherence in relation to SR-recall, unannounced pill counts, and common predictors of medication adherence.

Methods

Participants

One hundred eighty nine men, 94 women, and 15 transgender persons living with HIV/AIDS were recruited from AIDS service organizations, health care providers, social service agencies, and infectious disease clinics in inner-city areas of Atlanta, GA. Recruitment relied on provider referrals and word-of-mouth. Interested persons phoned our research program to schedule a study intake appointment. The study entry criteria were age 18 and proof of positive HIV status and HIV treatment status using a photo ID and matching ARV prescription bottle. All participants were being prescribed ARV medications. Data were collected November 2005 to October 2008.

Measures

The core assessments were administered using ACASI procedures. Participants viewed assessment items on a 15-inch color monitor, heard items read by machine voice using headphones, and responded by clicking a mouse. Research has shown that ACASI procedures yield reliable assessments of socially sensitive behaviors that are susceptible to biased responding [16, 17, 20, 21]. Participants were instructed to use the mouse prior to the assessment and were provided with assistance as needed.

Demographic and health characteristics

Participants were asked their age, years of education, income, ethnicity, and employment status. We assessed HIV related symptoms using a previously developed and validated measure concerning experience of 14 common symptoms of HIV disease. Participants also indicated whether they had ever been diagnosed with an AIDS-defining condition, and their most recent CD4 cell count and viral load.

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

The VAS for medication adherence was developed as an adjunct self-report measure of medication adherence [10]. The VAS asks individuals to mark a line at the point along a continuum showing how much of each drug they have taken in the past month. For the computerized administration we adapted the response format by using a 100 point slide bar tool anchored by 0%, 50% and 100%. The specific instructions read as follows “We would be surprised if most people take 100% of their medications. Below 0% means you have taken no [name of drug] this past month, 50% means you have taken half of your [name of drug] this past month and 100% means you have taken every single dose this past month. What percent of your [name of drug] did you take?” Participants indicated the percentage of medications taken by clicking their mouse anywhere on the 100 point slide bar continuum. We also administered the VAS during monthly interpersonal interviews conducted over the telephone using the exact same instructions as the computerized interviews.

Self-Reported Medication Recall (SR-recall)

Participants were interviewed to identify the HIV treatments they were currently taking and entered their regimen into the computerized interview system [22]. Next, the computerized interviewer asked participants to indicate the number of doses taken for each of their medications, one at a time, for each day in the previous week [22]. This section of the interview was repeated for each HIV medication in the participant’s regimen, asking participants to report the same information using the same procedures for the day before yesterday and the day before that and for the remaining four days of the week. The question algorithm used the following script:

How many times a day do you take [name of drug]? You take [name of drug] [response to above] times a day. How many of the [name of drug] pills are you supposed to take at each time? Think about yesterday. Did you miss taking ANY of your [name of drug] yesterday? How many times did you miss taking your [name of drug] yesterday? Now think about the day before yesterday, which would be 2 days ago. Did you miss taking ANY of you [name of drug] the day before yesterday? How many times did you miss taking your [name of drug] 2 days ago? Think about 3 days ago. Did you miss taking any of your [name of drug] 3 days ago? How many times did you miss taking your [name of drug] 3 days ago.

Now think about the entire past week or past 7 days. Other than the previous 3 days which you have already reported on, did you miss taking any of your [name of drug] in those other 4 days?

How many times did you miss taking your [name of drug] in those other 4 days?

The number of doses missed formed the basis for calculating adherence in the past week which was averaged across medications.

Unannounced Pill Counts (UPC)

Participants enrolled in this study consented to monthly unannounced telephone-based pill counts. Unannounced pill counts have been demonstrated reliable and valid in assessing HIV treatment adherence when conducted in participants’ homes [3] and on the telephone [5]. Following an office-based training in the pill counting procedure, participants were called at an unscheduled time by a phone assessor. Participants were provided with a free cell phone that restricted use for project contacts and emergency 911. Repeated pill counts occurred over 21 to 35 day intervals and were conducted for each of the ARV medications participants were taking. Pharmacy information from pill bottles was collected to verify the number of pills dispensed between calls. Adherence was calculated as the ratio of pills counted relative to pills prescribed and dispensed. Two consecutive pill counts were necessary for computing adherence. The adherence values reported here represent the percentage of pills taken as prescribed following the office-based assessment.

Correlates of adherence

The ACASI assessment included common correlates of medication adherence including reasons for missing medications, adherence self efficacy, substance use, and depression.

Reasons for missing medications

Participants indicated whether they had missed taking any of their medications in the previous month and if so the reasons they attributed to missing medication doses. Twelve common reasons for missing medications were adapted from previous research [23]. Participants may have missed multiple doses and therefore could indicate multiple reasons for missing medications.

Medication adherence self-efficacy

We assessed HIV treatment adherence self-efficacy using items adapted from a scale previously reported [24]. This scale was selected because it represents the type of instrument most commonly used to assess self-efficacy [25]. The seven self-efficacy items assessed confidence in one’s ability to overcome barriers to treatment adherence and maintain close adherence to medications, α = .86.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)

The AUDIT consists of 10 items designed to identify risks for alcohol abuse and dependence [26]. The first three items of the AUDIT represent quantity and frequency of alcohol use and the remaining seven items concern problems incurred from drinking alcohol. Scores on the AUDIT range from 0 – 40 and the AUIDT has demonstrated acceptable internal consistency. Scores of ≥ 8 indicate high-risk for alcohol use disorders and problem drinking.

Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST - 10)

The DAST-10 is an abbreviated version of the original scale, which was designed to identify drug-use related problems [27]. DAST-10 scores range from 0-10 and the scale is internally consistent, has demonstrated time stability and acceptable sensitivity and specificity in detecting drug abuse.

Depression

To assess current emotional distress we administered the Centers for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD, [28]). Participants were asked how often they had experiences and feelings characteristic of depression in the past 7 days, with responses made on the scale 0 = no days, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, 3 = 5–7 days. The 20 item CESD yields scores between 0 and 60, with a score of 16 indicating potential depression.

Procedures and data analyses

Participants completed informed consent followed by training in how to conduct the unannounced pill counts as described elsewhere [5]. Within three days of the training participants received their first unannounced pill count followed by unannounced monthly calls. Pill count adherence requires two consecutive data points to calculate adherence determined by pills missing relative to pills prescribed. Following two consecutive pill counts, participants returned to the research office to complete the computerized self-report assessment. The retrospective periods for the SR-recall and VAS therefore overlap with medication monitoring determined by pill counts within the same time periods. This research was approved by our institutional review board and was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Data analyses focused on descriptive statistics for adherence estimates derived from unannounced pill counts (UPC), SR-recall, and the VAS. We examined concordance between the measures of adherence using Pearson correlation coefficients for continuous percent of pills taken and Kappa coefficients for categorical values of adherence. The associations between adherence and viral load were tested using contingency table chi-square statistics. Significance for all analyses was defined as p < .05.

Results

Ninety percent (N = 270) of participants were African-American, 7% (N = 20) were White, and 3% (N = 8) were Hispanic. The average age was 44.7 (SD = 6.7) years old. One in four participants had not completed high school and 61% were disabled or unemployed.

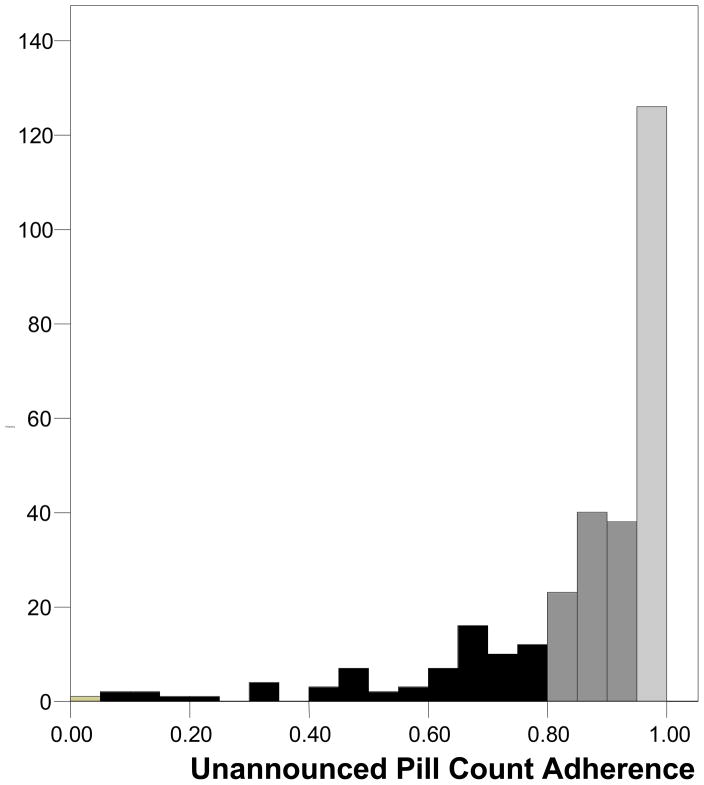

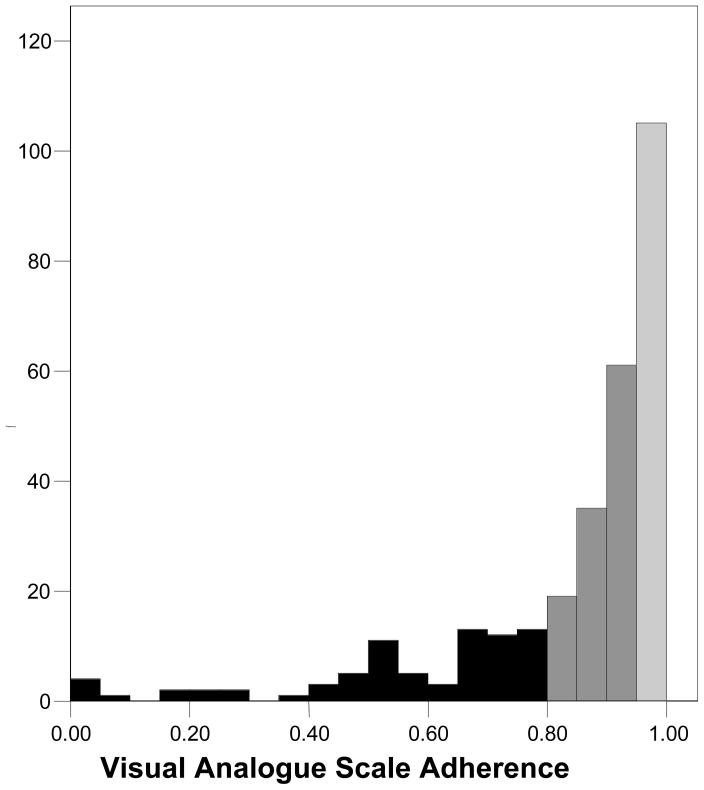

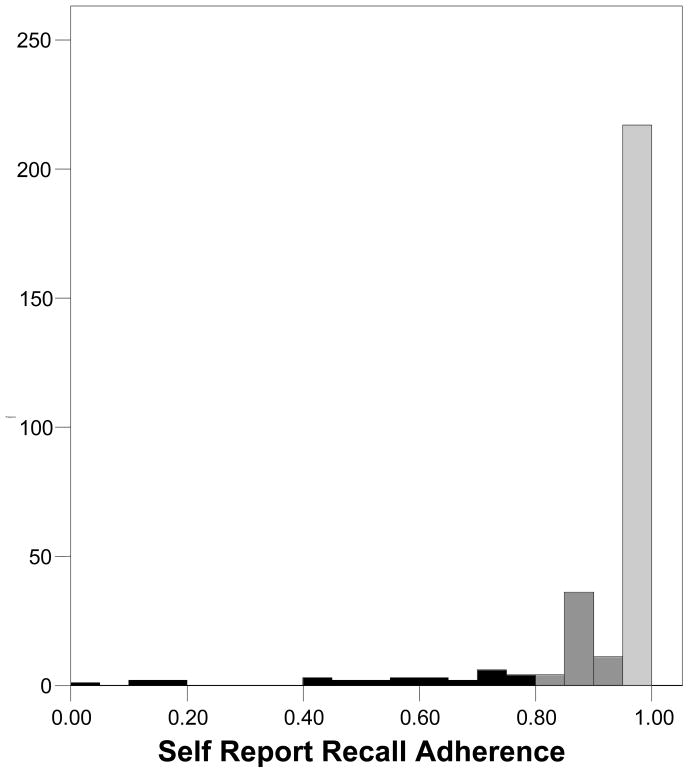

Table 2 presents the medication adherence estimates obtained from UPC, SR-recall, and the VAS. Results showed that SR-recall yielded higher estimates of adherence than both UPC and the VAS. Paired t-tests showed that the difference between UPC and SR-recall was significant, t (297) = 6.6, p < .01, as was the difference between the VAS and SR-recall, t (297) = 9.2, p < .01. The difference between UPC and the VAS was not significant, t (297) = 1.1, p > .1. More than two-thirds of participants indicated 100% adherence on the SR-recall measure compared to less than one-third for the VAS and one in five using UPC. At every level we observed greater adherence from the SR-recall measure than UPC and the VAS, with very similar patterns emerging from UPC and the VAS. Figures 1 through 3 show the frequency distributions of adherence for the three measures. The tendency for SR-recall to result in greater adherence is reflected in the distribution skew of −3.29, standard error (se) = .14, compared to the distribution skew for pill counts of −2.06, se = .14 and the VAS of −2.06, se = .14.

Table 2.

Adherence estimates for unannounced pill counts, self-reported recall, and visual analogue scale.

| UPC | SR-recall | VAS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 85.4 | 93.1 | 84.2 | |||

| Standard Deviation | 18.7 | 15.5 | 20.0 | |||

| Median | 92 | 100 | 92 | |||

| Adherence level | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| 100% | 47 | 16 | 206 | 69 | 96 | 32 |

| 95% | 112 | 38 | 213 | 72 | 101 | 34 |

| 90% | 157 | 52 | 223 | 75 | 163 | 55 |

| 85% | 197 | 66 | 236 | 79 | 195 | 65 |

| 80% | 225 | 76 | 267 | 89 | 219 | 74 |

| 75% | 233 | 78 | 271 | 91 | 231 | 78 |

| <75% | 65 | 22 | 27 | 9 | 67 | 22 |

Note: UPC = unannounced pill count, SR-recall = self-reported recall, VAS = visual analogue scale.

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution for adherence assessed by unannounced pill counts.

Figure 3.

Frequency distribution for adherence assessed by the visual analogue scale.

Concordance among measures of adherence

Pearson correlations among the three measures of adherence indicated moderate levels of association: UPC with VAS, r = .48; SR-recall with VAS, r = .58; and UPC with SR-recall r= .34, all significant p < .01. Similar results were obtained for concordance using categorical cut-offs to define adherence. Table 3 shows the resulting Kappa coefficients for adherence defined by categories based on percentages of medications taken. Agreement was moderate between the VAS and SR-recall and between VAS and UPC; Kappa coefficients ranging between .32 and .49. However, agreement between UPC and SR-recall was poor, with Kappa coefficients between .09 and .25.

Table 3.

Kappa coefficients of agreement at varying levels of adherence estimated by unannounced pills counts, self-reported recall, and visual analogue scale.

| Adherence level | UPC with SR-recall | SR-recall with VAS | UPC with VAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 95% | .21 | .46 | .40 |

| 90% | .19 | .38 | .39 |

| 85% | .25 | .44 | .46 |

| 80% | .17 | .43 | .45 |

| 75% | .09a | .32 | .49 |

Note: UPC = unannounced pill count, SR-recall = self-reported recall, VAS = visual analogue scale;

not significant, all other Kappa coefficients are significant, p < .05.

Computer administered VAS versus interpersonal interview

The telephone interview administered VAS yielded adherence assessments that correlated with the computer administered VAS (r = .70, p < .001). The mean adherence obtained by telephone VAS was 90.8% (SD = 14.3), which is significantly higher than that obtained by computerized interview, t (297) = 8.0, p < .01. With respect to categorical levels of adherence on the telephone interview VAS, 119 (41%) participants stated that they had perfect adherence; resulting in 78% agreement with the computerized administration, Kappa = .54, p < .01. Using 90% as the cutoff, 198 (68%) achieved adherence; 82% agreement with the computer administered VAS, Kappa = .61, p < .01. Overall, 69 (25%) participants indicated 100% adherence on the phone but not on the computer. Similarly, 45 (16%) participants who indicated at least 90% adherence on the telephone reported poorer adherence on the computer.

Correspondence of measures of adherence and viral load

Overall, 57% of participants reported knowing that their most recent viral load test result was undetectable, 31% indicated their viral load was detectable, and 12% indicated not knowing their viral load. For each measure and at each level of adherence, the association with viral load was significant, although the overall strength of the association was lowest for SR-recall at all levels of adherence (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations between three measures of adherence and self-reported viral load at high, moderate, and low levels of adherence.

| Viral Load | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Detectable | Undetectable | Not known | χ2 | |

| 95% adherence | ||||

| UPC | 25% | 69% | 6% | 13.2** |

| SR-recall | 28% | 62% | 10% | 7.5* |

| VAS | 20% | 73% | 7% | 18.4** |

| 85% adherence | ||||

| UPC | 28% | 62% | 10% | 7.6** |

| SR-recall | 28% | 61% | 11% | 9.3** |

| VAS | 25% | 66% | 9% | 20.1** |

| 75% adherence | ||||

| UPC | 28% | 62% | 10% | 10.7** |

| SR-recall | 30% | 59% | 11% | 7.7* |

| VAS | 28% | 62% | 10% | 15.6** |

Note: UPC = unannounced pill count, SR-recall = self-reported recall, VAS = visual analogue scale

p < .05,

p < .01.

Correlates of adherence

Table 5 shows the twelve reasons for missing medications indicated by participants with less than 85% of medications taken on each of the three adherence measures. Overall, when lower adherence was estimated by SR-recall, participants endorsed all of the reasons for missing doses more so than when lower adherence was estimated using UPC and VAS. In addition, reasons for missing doses were similar when participant adherence was estimated by UPC and VAS.

Table 5.

Reasons for missing medication doses among participants with less than 85% adherence on the three adherence measures.

| Reason for missing dose | UPC | SR-recall | VAS | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N = 94) | (N = 34) | (N = 96) | ||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Forgot | 70 | 74 | 31 | 91 | 82 | 85 |

| Pill not with participant | 20 | 21 | 11 | 32 | 31 | 32 |

| Too busy to take them | 37 | 39 | 19 | 56 | 42 | 43 |

| Too many pills to take | 8 | 9 | 5 | 15 | 11 | 12 |

| Medications make me sick | 20 | 21 | 12 | 35 | 21 | 22 |

| Did not want others to see me take pills | 8 | 9 | 6 | 18 | 11 | 12 |

| Slept through dose | 36 | 38 | 18 | 53 | 34 | 35 |

| Felt depressed or overwhelmed | 21 | 22 | 13 | 38 | 28 | 29 |

| Could not follow the directions | 7 | 7 | 7 | 21 | 9 | 9 |

| Too drunk or high | 9 | 9 | 8 | 24 | 8 | 8 |

| Traveling | 14 | 15 | 9 | 26 | 18 | 19 |

| Ran out of medications | 20 | 21 | 11 | 32 | 24 | 25 |

As shown in Table 6, estimates of adherence from the three measures varied in their associations with participant characteristics. Adherence assessed by UPC was significantly associated with participant health care, such that having private insurance was related to greater adherence. UPC adherence was also associated with self-efficacy, viral load, CD4 cell counts, HIV symptoms, alcohol and drug use, and depression. Adherence assessed by SR-recall presented a slightly different pattern of associations; SR-recall adherence correlated with older age, income, private insurance, self-efficacy, viral load and CD4 counts, HIV symptoms, drug use and depression. In contrast, the VAS was associated with most of the participant characteristics including age, income, private insurance, number of medications taken, self-efficacy, viral load and CD4 counts, HIV symptoms, alcohol and drug use, and depression.

Table 6.

Correlation coefficients between adherence measures and common factors associated with medication adherence.

| Participant characteristic | UPC | SR-recall | VAS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .02 | .15** | .11 |

| Education | −.04 | .06 | .08 |

| Income | .01 | −.16** | −.09 |

| Gender | .04 | .01 | −.02 |

| Private health care | .16** | .20** | .22** |

| Number of ARVs | −.07 | −.08 | −.12* |

| Self-efficacy | .37** | .42** | .49** |

| Viral Load | −.25** | −.15 | −.26* |

| CD4 cells | .13* | .13* | .19** |

| HIV symptoms | −.14** | −.13* | −.19** |

| AUDIT-alcohol | −.15** | −.10 | −.13* |

| DAST –drugs | −.12* | −.14* | −.14* |

| CESD - depression | −.14** | −.21** | −.25** |

Note: UPC = unannounced pill count, SR-recall = self-reported recall, VAS = visual analogue scale

p < .05,

p < .01.

Discussion

Two computer administered self-report measures of medication adherence differed in their evidence of validity. We found that the single item VAS yielded adherence rates and a distribution of adherence estimates that paralleled unannounced pill counts and differed from SR-recall. While SR-recall over-estimated adherence relative to pill counts, the values observed from the single item VAS paralleled those from UPC. Compared to UPC the ACASI administered VAS obtained nearly the same mean, median, and proportions of medications taken. Clinically relevant categories of adherence were also similar for the VAS and UPC. Unlike SR-recall adherence, participants with lower VAS adherence and unannounced pill counts reported similar reasons for missing doses. However, participants who were less than 85% adherent on the SR-recall measure reported more reasons for missing medications when compared to both UPC and VAS. The correlation between the ACASI VAS and SR-recall was the same as that reported in previous research [19]. Finally, VAS adherence and unannounced pill counts obtained a similar pattern of correlations with common adherence-related factors. Overall, we found that the VAS yielded results that paralleled those obtained from the far more expensive and burdensome unannounced pill counts.

Computer administration of self-report adherence measures may reduce socially desirable responding as occurs in measuring other sensitive behaviors. While we observed comparable adherence values for the VAS and UPC, adherence from SR-recall remained higher, suggesting socially desirable responding may differentially affect these two measures even when computer administered. Participants were more likely to report 100% adherence on SR-recall than VAS and participants who did report poorer adherence on SR-recall identified more variety of reasons for missing medications. Finally, SR-recall adherence correlated significantly with participant age and income, while neither UPC nor VAS were associated with participant demographic characteristics. Taken together, our findings support past research showing overestimated adherence and potentially biased responses obtained from SR-recall.

The current findings should be interpreted in light of their methodological limitations. Our self-reported adherence measures may have been influenced by social desirability bias. In addition, the UPC and VAS estimates of adherence were determined using a one month time frame whereas the SR-recall relied on a one week time frame in accordance with their standard use. The impact of using different time frames for the adherence measures is not known and could at least in part account for some of the observed differences. Our study was conducted with a convenience sample recruited in one city in the southeastern United States. The findings may therefore not be generalizable to other populations in other regions. With these limitations in mind, we believe that the current findings have important implications for assessing adherence in clinical and research settings.

We found that the single item VAS adherence scale provided comparable estimates of adherence as the far more expensive and burdensome unannounced pill counts. Indeed, the correlations between our computer administered self-report measures were similar to those reported in past research using ACASI administered adherence measures [19]. Trusting a single item measure of a complex behavior such as medication adherence requires a shift away from the convention that single item measures are inherently unreliable and inaccurate. Although researchers will not likely abandon the precision offered by objective measures of adherence, the VAS should be at least considered as an adjunct measure of adherence as it was initially intended [10]. It is also valuable that the VAS reflects patients awareness of their adherence. In clinical settings, however, where UPC may not be feasible for use in routine care, the VAS offers a simple, brief, and inexpensive option for measuring adherence with potentially minimal burden [29]. Future studies are needed to examine the feasibility of computer administered VAS adherence in clinical settings. The current findings are encouraging and when taken together with past research illustrate the VAS should be considered a valid index of medication adherence.

Figure 2.

Frequency distribution for adherence assessed by self-reported recall.

References

- 1.Kalichman SC, et al. Pillboxes and antiretroviral adherence: Prevalence of use, perceived benefits, and implications for electronic medication monitoring devices. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2005;19:49–55. doi: 10.1089/apc.2005.19.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen ML, et al. Pillbox organizers are associated with improved adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy and viral suppression: a marginal structural model analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;45:908–915. doi: 10.1086/521250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bangsberg DR, et al. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalichman SC, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy assessed by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2007;22:1003–1006. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0171-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalichman SC, et al. Monitoring Antiretroviral adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: Reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clinical Trials. 2008;9:298–308. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simoni J, et al. Self-Report Measures of Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence: A Review with Recommendations for HIV Research and Clinical Management. AIDS Behavior. 2006;10:227–331. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9078-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds NR, et al. Optimizing measurement of self-reported adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: a cross-protocol analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(4):402–9. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e318158a44f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chesney MA, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. Patient Care Committee & Adherence Working Group of the Outcomes Committee of the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–66. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garber MC, et al. The concordance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care. 2004;42(7):649–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000129496.05898.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giordano TP, et al. Measuring adherence to antiretroviral therapy in a diverse population using a visual analogue scale. HIV Clinical Trials. 2004;5:74–79. doi: 10.1310/JFXH-G3X2-EYM6-D6UG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh JC, Dalton M, Gazzard BG. Adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy assessed by anonymous patient self-report. AIDS. 1998;12(17):2361–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oyugi JH, et al. Multiple validated measures of adherence indicate high levels of adherence to generic HIV antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36(5):1100–2. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dejesus E, et al. Simplification of antiretroviral therapy to a single-tablet regimen consisting of efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus unmodified antiretroviral therapy in virologically suppressed HIV-1-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(2):163–74. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a572cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gill CJ, et al. Importance of Dose Timing to Achieving Undetectable Viral Loads. AIDS Behav. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson CR, et al. Assessing antiretroviral adherence via electronic drug monitoring and self-report: an examination of key methodological issues. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):161–73. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9133-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gribble JN, et al. Interview mode and measurement of sexual and other sensitive behaviors. Journal of Sex Research Articles. 1999;36:16–24. doi: 10.1080/00224499909551963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gribble JN, et al. The impact of T-ACASI interviewing on reported drug use among men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(6–8):869–90. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bangsberg DR, et al. Computer-assisted self-interviewing (CASI) to improve provider assessment of adherence in routine clinical practice. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;31(Suppl 3):S107–11. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200212153-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amico KR, et al. Visual analog scale of ART adherence: association with 3-day self-report and adherence barriers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(4):455–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225020.73760.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waruru AK, Nduati R, Tylleskar T. Audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) may avert socially desirable responses about infant feeding in the context of HIV. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):541–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ickovics JR, Meisler AW. Adherence in AIDS clinical trials: a framework for clinical research and clinical care. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):385–91. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catz SL, et al. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000;19(2):124–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gifford AL, et al. Predictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimens. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;23(5):386–95. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saunders JB, et al. Addictions. 6. Vol. 88. 1993. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II; pp. 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skinner H. The Drug Abuse Screening Test. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psych Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deschamps AE, et al. Diagnostic value of different adherence measures using electronic monitoring and virologic failure as reference standards. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2008;22(9):735–43. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]