Abstract

Background

Aiming at therapeutic targets has reduced the risk of organ failure in many diseases such as diabetes or hypertension. Such targets have not been defined for rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Objective

To develop recommendations for achieving optimal therapeutic outcomes in RA.

Methods

A task force of rheumatologists and a patient developed a set of recommendations on the basis of evidence derived from a systematic literature review and expert opinion; these were subsequently discussed, amended and voted upon by >60 experts from various regions of the world in a Delphi-like procedure. Levels of evidence, strength of recommendations and levels of agreement were derived.

Results

The treat-to-target activity resulted in 10 recommendations. The treatment aim was defined as remission with low disease activity being an alternative goal in patients with long-standing disease. Regular follow-up (every 1–3 months during active disease) with appropriate therapeutic adaptation to reach the desired state within 3 to a maximum of 6 months was recommended. Follow-up examinations ought to employ composite measures of disease activity which include joint counts. Additional items provide further details for particular aspects of the disease. Levels of agreement were very high for many of these recommendations (≥9/10).

Conclusion

The 10 recommendations are supposed to inform patients, rheumatologists and other stakeholders about strategies to reach optimal outcomes of RA based on evidence and expert opinion.

Introduction

Over the past 15 years, rheumatologists have developed and witnessed many paradigmatic changes in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, these insights have not yet been clearly formulated. Consequently, many of these changes have not been brought into effect in most countries in Europe and other parts of the world.

In many other areas of medicine, treatment targets have been defined to improve outcomes, leading to a reduction in the risk of organ damage.1–7 In the care of patients with diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and hypertension, these aspects have been adopted widely in practice; doctors order laboratory tests for cholesterol and triglycerides, blood glucose and HbA1c levels, check blood pressure and adapt therapy accordingly, and patients know these values and are aware of the treatment targets.

In RA, joint damage and physical disability are the major adverse outcomes associated with reduction in quality of life and premature mortality.8–11 In turn, disease activity—as reflected by swollen joint counts, levels of acute phase reactants or by composite indices of disease activity—is a good predictor of damage and physical disability.12–20

The paradigmatic changes mentioned above are related to several factors. First, less joint damage and better physical function have been unequivocally shown to be a consequence of the early institution of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) when compared with their delayed start.21 22 Second, the definition of core set variables and development of composite measures to assess RA has allowed disease activity to be assessed reliably.23–26 Third, newly licensed medications, especially biological agents, have enabled the attainment of unprecedented outcomes.23 27 Fourth, structured patient management aiming for a treatment target, usually low disease activity (LDA), leads to better outcomes than traditional means of follow-up.28–30

Finally, today remission is an achievable goal in many patients in clinical trials and clinical practice,31–34 and rapid attainment of remission can halt joint damage irrespective of the type of DMARD, synthetic or biological.20 Nevertheless, patients enrolled in recent clinical trials have often received only a very small number of DMARDs despite long disease duration,35–37 indicating inadequate treatment, although rheumatologists appear to be well-informed of recent insights on treating RA.38

The objective of the task force was to formulate a consensus on a set of recommendations aimed at improving the management of RA in clinical practice, thus providing guidance for treatment to target (‘T2T’). The consensus finding was based on evidence obtained from a systematic literature review which revealed improved outcomes with strategic therapeutic approaches.39

Methods

This activity comprised several steps. First, a Steering Committee consisting of rheumatologists and a patient with RA (the authors), who were identified on the basis of their expertise in treating RA, participation in clinical trials, development of consensus statements and regional distribution across Europe and North America, was assembled in 2008.

The Steering Committee regarded a comprehensive systematic literature review as a mandatory initial step to serve as a basis for consensus on the definition of treatment targets. After definition of search questions, the literature review was performed by a fellow (MS) and is published in detail as an accompanying paper.39 On this basis, the Steering Committee formulated a provisional set of recommendations in line with European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) standardised operating procedures40 at a second meeting.

In March 2009 these provisional recommendations were presented for discussion, amendment and voting to more than 60 experts from Europe, North and Latin America, Japan and Australia, including five patient representatives. The level of evidence and strength of each recommendation were determined41 42 and categorised as A (highest) to D (lowest) on the basis of the systematic literature review39 as ratified by the Steering Committee.

Discussions took place in breakout and plenary sessions at the expert summit and decisions were made using a modified Delphi technique.43 Each statement was then voted upon in an anonymous fashion using a digital system. Statements supported by ≥75% of votes were accepted while those with ≤25% were rejected outright. Others were subjected to further discussion and subsequent voting where ≥67% support or, in an eventual third round, a majority of ≥50% was needed. Subsequently, the group voted on the level of agreement with each of the derived bullet points using a 10-point numerical rating scale (1=do not agree at all, 10=agree completely).

The statements were then sent by email for final comments. Only suggestions for improvements of clarity of wording or removal of redundancies were considered. Proposed changes to the meaning were not accepted, although they will be mostly dealt with in the comments to each bullet point.

Results

Evidence-based approach

The final step of the systematic literature review included only 19 full papers and 5 recent abstracts that had targeted therapy as a research focus. The results are published in detail in an accompanying paper.39

Statements

The statements receiving a majority vote by the Expert Committee in the final voting round are shown in Box 1. These are discussed in detail below.

Overarching principles

The Committee felt that certain aspects related to the treatment of RA form a framework on which specific recommendations can be based. These items were therefore considered to constitute overarching principles, although they were discussed and voted on.

(A) The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis must be based on a shared decision between patient and rheumatologist. Not only must the patient be informed on the therapeutic options and the reasons for recommending a particular therapeutic approach by weighing benefit and risk, but the patient should participate in the decision as to which treatment should be applied. This item was accepted unanimously.

(B) The primary goal of treating the patient with rheumatoid arthritis is to maximise long-term health-related quality of life through control of symptoms, prevention of structural damage, normalisation of function and social participation. This general statement pertains to all aspects of the therapeutic procedures including selection of drugs, application of treatment strategies and follow-up of RA (81.6% acceptance).

(C) Abrogation of inflammation is the most important way to achieve these goals. This principle relates to the fact that the inflammatory response underlying RA is responsible for the signs and symptoms of the disease and is associated with adverse outcomes in all areas listed in (B)12 13 19 44 45 (72.9% acceptance in the second voting round). There was discussion as to whether the term ‘abrogation’ could be easily translated into other languages; to this end, synonyms such as abolition, reversal, suppression, halt, arrest, stop or inhibition reflect the meaning, although abrogation leaves less room for residual interpretations than most other terms.

(D) Treatment to target by measuring disease activity and adjusting therapy accordingly optimises outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis. While the endeavour was to focus on individual items related to the topic of T2T, the Expert Committee felt so convinced on the principal nature and truthfulness of this statement that 91.8% of the experts accepted it.

Recommendations

The overarching principles are followed by the final set of 10 recommendations as formulated by the Expert Committee. The sequence follows a hierarchical and a logical order; for example, the first statement was regarded as the most important one, but other items were also deemed important. The weight of the individual items is reflected by the level of evidence, the strength of recommendation and level of agreement as presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Evidence, agreement and votes for each of the recommendations

| Item | Category of evidence | Strength of recommendation | Level of agreement | Percentage of votes at last ballot (number of ballots*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | III | C | 9.1 | 83 (1) |

| 2 | IV | D | 7.8 | 76 (8) |

| 3 | Ib | A | 8.6 | 77 (3) |

| 4 | Ib | A | 8.7 | 77 (6) |

| 5 | IV | D | 8.5 | 53 (3) |

| 6 | IV | D | 9.0 | 93.4 (5) |

| 7 | IV | D | 9.3 | 79.6 (9) |

| 8 | III | C | 9.7 | 92.6 (1) |

| 9 | IV | D | 9.5 | 74.5 (3) |

| 10 | IV | D | 9.3 | 90.6 (4) |

For several of the items the number of votes relates to the details of the wording, while the inclusion of the statement has been agreed upon at earlier ballots.

(1) The primary target for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis should be a state of clinical remission. The level of evidence supporting this statement was low (category III or IV) because strategic trials have hitherto aimed at attaining LDA,28–30 while no formal study compared a strategy to treat RA with the target ‘remission’ with another strategy. Some trials evaluated the frequencies of remission by different therapies46 or had remission as the primary end point32 46 but, with one exception,46 this was investigated with static treatment and not by strategic switching. On the other hand, the functional and radiographic outcomes of these latter trials provide important supportive evidence for the statement. Also, subanalyses of various clinical trials suggest that the best outcomes are achieved on attaining remission, even when compared with LDA.20 47 Moreover, remission can be achieved in a significant proportion of patients, especially with early RA. It was therefore deemed to be a pivotal aspirational target for all patients (83% support; average agreement 9.1/10). The importance of sustained remission is addressed later.

(2) Clinical remission is defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease activity. This statement is entirely expert-based (category IV). While there are many definitions of remission, such as that by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) or based on composite disease activity measures14 48 49 and all of them are contained in the EULAR/ACR recommendations for clinical trial reporting,50 51 it is well established that some criteria allow for more residual disease activity than others.14 52 53 Furthermore, even when swelling cannot be discerned clinically, it may continue to exist at a subclinical level.54 55 The majority of the experts felt that the definition of remission should not allow for residual clinical disease activity. On the other hand, it was accepted that some residual joint tenderness or a single swollen joint in a patient with long-standing disease may still be compatible with a state of remission. The term remission of ‘inflammatory disease activity’ was therefore coined, given that joint swelling and C-reactive protein (CRP) but not isolated tenderness or pain are associated with progression of joint damage.13 The term ‘significant’ makes clear that a higher than very small level of residual inflammatory activity was not acceptable, in line with survey results.56 In this regard, acute phase reactants such as CRP have also to be taken into account, as their increase likewise reflects inflammatory disease activity (see also statement 9). The final voting achieved approval by 76% of the experts. An ACR/EULAR initiative on defining remission is currently ongoing.

Box 1. Recommendations.

Overarching principles

The treatment of rheumatoid arthritis must be based on a shared decision between patient and rheumatologist.

The primary goal of treating the patient with rheumatoid arthritis is to maximise long-term health-related quality of life through control of symptoms, prevention of structural damage, normalisation of function and social participation.

Abrogation of inflammation is the most important way to achieve these goals.

Treatment to target by measuring disease activity and adjusting therapy accordingly optimises outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis.

10 recommendations on treating rheumatoid arthritis to target based on both evidence and expert opinion:

The primary target for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis should be a state of clinical remission.

Clinical remission is defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease activity.

While remission should be a clear target, based on available evidence low disease activity may be an acceptable alternative therapeutic goal, particularly in established long-standing disease.

Until the desired treatment target is reached, drug therapy should be adjusted at least every 3 months.

Measures of disease activity must be obtained and documented regularly, as frequently as monthly for patients with high/moderate disease activity or less frequently (such as every 3–6 months) for patients in sustained low disease activity or remission.

The use of validated composite measures of disease activity, which include joint assessments, is needed in routine clinical practice to guide treatment decisions.

Structural changes and functional impairment should be considered when making clinical decisions, in addition to assessing composite measures of disease activity.

The desired treatment target should be maintained throughout the remaining course of the disease.

The choice of the (composite) measure of disease activity and the level of the target value may be influenced by consideration of co-morbidities, patient factors and drug-related risks.

The patient has to be appropriately informed about the treatment target and the strategy planned to reach this target under the supervision of the rheumatologist.

(3) While remission should be a clear target, based on available evidence low disease activity may be an acceptable alternative therapeutic goal, particularly in established long-standing disease. This statement confirms remission as the ultimate therapeutic goal. Nevertheless, since all strategic clinical trials have focused on LDA,28–30 the target with the best evidence is a state of LDA according to established cut-off points of composite measures (category Ib). In patients with long-standing disease, considerable joint damage and several prior treatment failures, remission may not be realistic and LDA may be the best achievable state. Indeed, many patients with established RA may prefer to accept an ‘LDA state’ above forcing them into remission at all costs. Importantly, however, LDA should be the minimal aspired goal (an ‘acceptable alternative to remission’), and patients clearly should not remain in moderate or high disease activity states. Finally, when LDA is an alternative target, it is important to sustain it (as was stated for remission; see also point 8).

(4) Until the desired treatment target is reached, drug therapy should be adjusted at least every 3months. Clinical trials suggest that the maximal clinical benefit is usually not achieved before 3 months of treatment. A change of DMARD therapy has been done successfully every 1–3 months in strategic trials.28 30 Thus, if patients do not attain at least a state of LDA within 3 months from starting therapy, treatment should be amended (category Ib). This does not necessarily mean a change of drugs, since the degree of the change of disease activity from baseline has to be taken into account in individual patients, especially in those with high disease activity at the start of therapy. Dose adaptation of existing medication may be sufficient for further benefit to be judged over the subsequent 1–3 months. On the other hand, in patients in whom the disease activity did not show major improvement within 3 months, changing the drug regimen may have to be considered at that early point in time. The choice of this time point is supported by respective studies.28–30 47 57

(5) Measures of disease activity must be obtained and documented regularly, as frequently as monthly for patients with high/moderate disease activity or less frequently (such as every 3–6months) for patients in sustained low disease activity or remission. Progression of joint damage can be recognised within a few weeks in patients with high disease activity.58 Therefore, in patients with high disease activity, there is a need for frequent assessment of the disease status (eventually even monthly) to adapt treatment accordingly (category Ib). Once patients reach remission (or the alternative goal of LDA when having long-standing RA) and sustain this state, less frequent evaluations may be sufficient. The focus here is on the term ‘sustained’, indicating that even if a particular desired state is reached, more frequent control examinations are necessary initially to ensure that the state does not change (ie, rebound) rapidly. The first example for high disease activity, ‘as frequently as monthly’, leans against available strategic trials evaluating patients every 1–3 months28 30 in high disease activity. The other example, ‘such as every 3–6 months’ has been a compromise constituting expert opinion, since some rheumatologists feared short-term reactivation of RA which could be detected early with 3-monthly examinations. Among patients who are in sustained remission and are adequately informed to see their rheumatologist earlier upon status changes, annual control examinations may suffice.

(6) The use of validated composite measures of disease activity, which include joint assessments, is needed in routine clinical practice to guide treatment decisions. The Committee was convinced that using composite measures of disease activity constitutes the best way to judge disease activity and response to therapy, although this is an expert opinion (category IV). RA is heterogeneous and composite scores capture this heterogeneity best.59 60 There exist several validated composite measures of disease activity which comprise joint assessment.61 Importantly, the vast majority of the experts felt that these measures should include joint assessments, because the joints constitute the ‘organ’ involved in RA and using measures that do not contain joint counts may lack face validity or not be accurate (influenced by factors not related to the disease). Indeed, this item as it stands achieved one of the highest levels of agreement (9.0). Recent EULAR/ACR guidelines for clinical trial reporting mention validated composite measures that include joint counts obtained by a rheumatologist or other health professional, such as the disease activity score (DAS) or the DAS employing 28 joint counts (DAS28), the simplified and the clinical disease activity index (SDAI, CDAI)50 51; these measures are also useful in clinical practice. To leave the choice open for the clinician, the neutral term ‘composite measure of disease activity’ was used.

(7) Structural changes and functional impairment should be considered when making clinical decisions, in addition to assessing composite measures of disease activity. This item reiterates the importance of using composite measures of disease activity, but indicates that other aspects such as functional impairment and joint damage, which are governed by the degree of disease activity, also have to be considered. However, in the shorter term, the majority of patients even with high disease activity will not experience progression of joint destruction.62 Thus, the effect of active disease on radiographic damage varies between patients. The committee felt that x-rays should be obtained annually and potential progression of joint damage be estimated (not scored). If joint damage appears to progress despite achieving the desired target such as LDA, intensifying treatment may be needed (category IV). However, lag periods of x-ray progression may have to be considered.63 This bullet point does not mention x-rays, indicating that other instruments known (validated) to inform us on joint damage may also be used; this relates particularly to MRI and sonography. Importantly, judgements should be made by those sufficiently experienced in reading these images. In addition to joint damage, continuing impairment of physical function despite achievement of the targeted disease activity level may also necessitate a therapeutic change (category IV). However, in some patients, functional impairment may not be sufficiently captured by functional measures, particularly in individuals with certain occupations who experience reduction in functioning and personal working capacity by involvement of a specific joint, necessitating a change of treatment even if otherwise in LDA. Thus, special treatment options may be needed for optimal caretaking of individual patients.

(8) The desired treatment target should be maintained throughout the remaining course of the disease. Once disease activity has been titrated to the desired therapeutic target such as remission, this state should be maintained continuously (category III). First, only sustained/persistent remission will lead to a halt in damage20 63; second, any increase in disease activity may reignite the destructive process.64 Caution is needed to govern decisions to reduce (dose or interval of) synthetic or biological DMARD treatment, let alone stopping it. Stopping synthetic DMARD therapy in remission was followed by twice as many flare-ups and difficulties in reintroducing remission.65 Similar studies are not available for the biological agents.

(9) The choice of the (composite) measure of disease activity and the level of the target value may be influenced by consideration of co-morbidities, patient factors and drug-related risks. Measures of disease activity, such as DAS, DAS28, SDAI, CDAI, comprise several variables and some of these may be affected by comorbidities or other patient factors and thus partly invalidate the result obtained (category IV). For example, tender joints and patient's assessment of disease activity may be exaggerated in certain concomitant diseases such as fibromyalgia; or when erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is employed, diseases with abnormalities of the ESR may influence the score. It is then necessary to interpret the individual components of composite measures. Likewise, the target value may have to be eased in patients with certain comorbidities (or certain comedications); such comorbidities may be chronic infections, renal or hepatic functional impairment, congestive heart failure and others.

(10) The patient has to be appropriately informed about the treatment target and the strategy planned to reach this target under the supervision of the rheumatologist. This statement is a separate item to remind all health professionals who care for patients with RA that discussing with the patient the reasons for aiming at the selected target, the therapeutic options available and the strategies planned to reach the target is of utmost importance (category IV). Likewise, it is paramount that a rheumatologist defines the target with the patient, directs the strategy chosen and follows the patient over time, since other professions are less well informed on the disease itself, the benefits and risks of individual agents to treat RA and the risks of comorbidities. In this regard, it may constitute a challenge to inform patients with early RA on the need of intensive medication or patients with relatively mild symptoms on the necessity to adjust therapy. This item therefore also implies the importance of patient education programmes in a specific structured way, as well as the design of programmes to help health professionals address the appropriate issues with their patients.

Evidence and agreement

For all statements, the category of evidence and the strength of recommendation have been determined in accordance with the systematic literature review39 and are shown in table 1. In addition, the level of agreement as determined during the final ballot at the Expert Committee meeting is provided (table 1). For reasons of transparency, we also show the number of ballots needed for the final formulation of the statements as well as the percentage of participants who voted for that formulation. The level of agreement ranged from 7.8 to 9.7 on a 10-point scale.

Discussion

The recommendations presented are based on a combination of a systematic literature review and expert opinion.

The process was initiated by a Steering Committee which adhered to the EULAR operating procedures for the development of recommendations.40 It was finalised after discussions by more than 60 experts from all over the world. Importantly, five patients were among these experts. The very high level of agreement on most of the statements is also noteworthy and, given that the Expert Group came from so many countries and regions of the world, this agreement implies a broad international recognition and consensus.

The recommendations were formulated with the optimal outcome of RA in practice in mind. They do not account for potential financial constraints or access to particular therapies, since no one particular type of therapy was the focus of attention but rather the therapeutic target that needs to be attained, independent of accessibility. However, with different accessibilities, different proportions of patients may be able to attain the desired target, although it has been shown that adhering to treatment strategies may significantly improve outcomes even when easily accessible and affordable therapies are employed.28–30

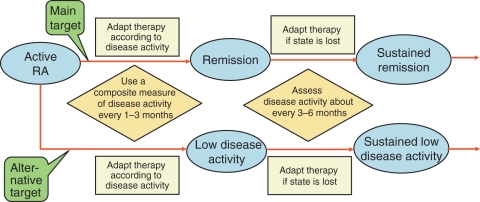

As its major conclusion, the Expert Committee was almost unanimous that remission must be the ultimate therapeutic goal in RA. However, since no therapeutic trial has studied this approach—for instance, by comparing it with the aim of achieving LDA—this recommendation is actually expert-based although it is supported by a large body of circumstantial evidence. True evidence exists for the beneficial effect of treating RA to a target of LDA in a structured strategic way when compared with non-structured therapy.28 29 However, the Expert Committee felt that, while being an important step and a major alternative goal, reaching LDA could only pertain to patients with long-standing RA whose disease may have become refractory to therapeutic intervention. In contrast, in early RA, LDA should only be an intermediate step on the way to remission. The overall targeted therapeutic approach is summarised in a simplified form in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to target based on the recommendations provided in box 1 and discussed in more detail in the explanatory notes. Indicated as separate threads are the main target (remission and sustained remission) and the alternative target (low disease activity in patients with long-term disease), but the approaches to attain the targets and sustain them are essentially identical. Adaptation of therapy should usually be done by performing control examinations with appropriate frequency and using composite disease activity measures which comprise joint counts.

While several items provide additional guidance in relation to the major statements (1) and (3), three additional recommendations stick out in the context of current practice, namely numbers (4), (5) and (6). Recommendation (6) received one of the highest votes and levels of agreement and calls for the need to use composite disease activity measures which include joint counts in the follow-up of patients with RA. Indeed, 93.4% of the experts voted to include joint assessments. Items (4) and (5) recommend adjustment of therapy at least every 3 months if the therapeutic target is not reached and to assess patients with higher disease activity states within a shorter term and thus up to monthly to allow timely adaptation of therapy.

These recommendations come at a time when both remission and LDA are achievable goals with the current therapeutic armamentarium.31 32 The recommendations are primarily meant to provide guidance on ways towards this goal, as seen by experts. They are aimed at all stakeholders: patients who are informed by these statements on the optimal strategies to prevent or contain damage and disability; rheumatologists and other health professionals who may further their drive to do the best for the patients; and also official bodies such as governments or payers which may wish to use this document as a reference for the assessment of success in treating patients with RA in their environment.

Many sets of recommendations have been developed in the past for treating early and established RA.66–68 However, none of these comprised the important aspects of specifically defining the treatment target for RA and detailing the ways to achieve the therapeutic goal. This is now provided with the present set of recommendations. Bringing them into practice will enable the prevention of progression of joint damage and reversal of physical disability, a pivotal goal for the new decade.

Recommendations such as those presented here usually elicit a number of research questions. This research agenda is implicitly indicated by the contents of all statements with category IV evidence; it would be important to perform studies which examine the evidence for these expert opinions. On the other hand, many of these category IV recommendations are based on a large array of indirect evidence so it would also be worthwhile to look into the possibility of improving the appraisal of evidence under such terms and circumstances by assigning special levels.

Footnotes

Additional members of the T2T Expert Committee Jose Louis Andreu (Spain), Martin Bergman (USA), Harald Burkhardt (Germany), Vivian Bykerk (Canada), Mario Cardiel (Mexico), Filip Codruta (Romania), Hector Corominas (Spain), Alexandros Drosos (Greece), Patrick Durez (Belgium), Hani ElGabalawy (Canada), Cristina Estrach (UK), Bruno Fautrel (France), Gianfranco Ferracioli (Italy), Roy Fleischman (USA), Joao Eurico Fonseca (Portugal), Cem Gabay (Switzerland), Clara Gjesdal (Norway), Laure Gossec (France), Winfried Graninger (Austria), Espen Haavardsholm (Norway), Sesilie Halland (Norway), Pekka Hannonen (Finland), Jamie Henderson (Canada), Jonathan Kay (USA), Wenche Koldingsnes (Norway), Marios Kouloumas (Cyprus), Ieda Maria Laurindo (Brazil), Marjatta Leirisalo-Repo (Finland), Carlomaurizio Montecucco (Italy), Peter Nash (Australia), Mikkel Ostergaard (Denmark), Andrew Ostor (UK), Karel Pavelka (Czech Republic), José Peirera da Silva (Portugal), Kim Horslev Peterson (Denmark), Duncan Porter (UK), Enid Quest (UK), Evangelos Romas (Australia), Marieke Scholte (The Netherlands), Luigi Sinigaglia (Italy), Tuulikki Sokka (Finland), Ewa Stanislawska (Poland), Tsutomu Takeuchi (Japan), Guillermo Tate (Argentina), Athanasios Tzioufas (Greece), Peter Villiger (Switzerland).

Competing interests This work was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Immunology. Abbott affiliates were not involved in the programme or any voting. At the end of the voting process, the Expert Committee was asked to vote in an anonymous fashion if they felt they had been influenced by the sponsoring of the event by Abbott. This ballot resulted in an agreement of 8.7/10 that they did not consider that the fact that Abbott was sponsoring this programme created a bias. The handling editor was F Berenbaum.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rachmani R, Slavacheski I, Berla M, et al. Treatment of high-risk patients with diabetes: motivation and teaching intervention: a randomized, prospective 8-year follow-up study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005;16(Suppl 1):S22–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eeg-Olofsson K, Cederholm J, Nilsson PM, et al. Glycemic and risk factor control in type 1 diabetes: results from 13,612 patients in a national diabetes register. Diabetes Care 2007;30:496–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:829–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egan BM, Lackland DT, Cutler NE. Awareness, knowledge, and attitudes of older americans about high blood pressure: implications for health care policy, education, and research. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:681–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pearson TA. The epidemiologic basis for population-wide cholesterol reduction in the primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2004;94:4F–8F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mora S, Musunuru K, Blumenthal RS. The clinical utility of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in cardiovascular disease and the potential implication of JUPITER on current practice guidelines. Clin Chem 2009;55:219–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell DM, Spitz PW, Young DY, et al. Survival, prognosis, and causes of death in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:706–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus T, Callahan LF, Sale WG, et al. Severe functional declines, work disability, and increased mortality in seventy-five rheumatoid arthritis patients studied over nine years. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:864–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Gefeller O, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:1530–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yelin E, Trupin L, Wong B, et al. The impact of functional status and change in functional status on mortality over 18 years among persons with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002;29:1851–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawes PT, Fowler PD, Clarke S, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis: treatment which controls the C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate reduces radiological progression. Br J Rheumatol 1986;25:44–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Leeuwen MA, van der Heijde DM, van Rijswijk MH, et al. Interrelationship of outcome measures and process variables in early rheumatoid arthritis. A comparison of radiologic damage, physical disability, joint counts, and acute phase reactants. J Rheumatol 1994;21:425–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aletaha D, Ward MM, Machold KP, et al. Remission and active disease in rheumatoid arthritis: defining criteria for disease activity states. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:2625–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolen JS, Van Der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Predictors of joint damage in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with high-dose methotrexate with or without concomitant infliximab: results from the ASPIRE trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:702–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Heijde DM, van Riel PL, van Leeuwen MA, et al. Prognostic factors for radiographic damage and physical disability in early rheumatoid arthritis. A prospective follow-up study of 147 patients. Br J Rheumatol 1992;31:519–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Combe B, Cantagrel A, Goupille P, et al. Predictive factors of 5-year health assessment questionnaire disability in early rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:2344–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Welsing PM, Landewé RB, van Riel PL, et al. The relationship between disease activity and radiologic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a longitudinal analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2082–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drossaers-Bakker KW, de Buck M, van Zeben D, et al. Long-term course and outcome of functional capacity in rheumatoid arthritis: the effect of disease activity and radiologic damage over time. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1854–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde DM, et al. Radiographic changes in rheumatoid arthritis patients attaining different disease activity states with methotrexate monotherapy and infliximab plus methotrexate: the impacts of remission and tumour necrosis factor blockade. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:823–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lard LR, Visser H, Speyer I, et al. Early versus delayed treatment in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: comparison of two cohorts who received different treatment strategies. Am J Med 2001;111:446–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nell VP, Machold KP, Eberl G, et al. Benefit of very early referral and very early therapy with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:906–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, et al. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2007;370:1861–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary core set of disease activity measures for rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. The Committee on Outcome Measures in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. Arthritis Rheum 1993;36:729–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Heijde DM, van't Hof M, van Riel PL, et al. Development of a disease activity score based on judgment in clinical practice by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol 1993;20:579–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:244–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feldmann M, Maini RN. Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award. TNF defined as a therapeutic target for rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases. Nat Med 2003;9:1245–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grigor C, Capell H, Stirling A, et al. Effect of a treatment strategy of tight control for rheumatoid arthritis (the TICORA study): a single-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:263–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, van der Veen MJ, et al. Intensive treatment with methotrexate in early rheumatoid arthritis: aiming for remission. Computer Assisted Management in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAMERA, an open-label strategy trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1443–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, et al. Comparison of treatment strategies in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:406–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mierau M, Schoels M, Gonda G, et al. Assessing remission in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:975–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet 2008;372:375–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emery P, Salmon M. Early rheumatoid arthritis: time to aim for remission? Ann Rheum Dis 1995;54:944–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sokka T, Hetland ML, Mäkinen H, et al. Remission and rheumatoid arthritis: Data on patients receiving usual care in twenty-four countries. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2642–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emery P, Keystone E, Tony HP, et al. IL-6 receptor inhibition with tocilizumab improves treatment outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti-tumour necrosis factor biologicals: results from a 24-week multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1516–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smolen JS, Landewé RB, Mease P, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:797–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Pincus T, et al. Disparities in rheumatoid arthritis disease activity according to gross domestic product in 25 countries in the QUEST-RA database. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1666–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoels M, Aletaha D, Smolen JS, et al. Follow-up standards and treatment targets in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): results of a questionnaire at the EULAR 2008. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:575–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schoels M, Wong J, Scott DL, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dougados M, Betteridge N, Burmester GR, et al. EULAR standardised operating procedures for the elaboration, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation of recommendations endorsed by the EULAR standing committees. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1172–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ 1999;318:593–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The AGREE Collaboration Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Safe Health Care 2003;12:18–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visser K, van der Heijde D. Optimal dosage and route of administration of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1094–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welsing PM, van Gestel AM, Swinkels HL, et al. The relationship between disease activity, joint destruction, and functional capacity over the course of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2009–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aletaha D, Smolen J, Ward MM. Measuring function in rheumatoid arthritis: Identifying reversible and irreversible components. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2784–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Möttönen T, Hannonen P, Leirisalo-Repo M, et al. Comparison of combination therapy with single-drug therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised trial. FIN-RACo trial group. Lancet 1999;353:1568–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aletaha D, Funovits J, Smolen JS. The importance of reporting disease activity states in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2622–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinals RS, Masi AT, Larsen RA. Preliminary criteria for clinical remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1981;24:1308–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fransen J, Creemers MC, Van Riel PL. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: agreement of the disease activity score (DAS28) with the ARA preliminary remission criteria. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:1252–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1360–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1371–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Boers M, et al. Comparison of different definitions to classify remission and sustained remission: 1 year TEMPO results. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1582–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mäkinen H, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, et al. Is DAS28 an appropriate tool to assess remission in rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1410–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown AK, Conaghan PG, Karim Z, et al. An explanation for the apparent dissociation between clinical remission and continued structural deterioration in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:2958–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown AK, Quinn MA, Karim Z, et al. Presence of significant synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis patients with disease-modifying antirheumatic drug-induced clinical remission: evidence from an imaging study may explain structural progression. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3761–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aletaha D, Machold KP, Nell VP, et al. The perception of rheumatoid arthritis core set measures by rheumatologists. Results of a survey. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1133–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soubrier M, Puéchal X, Sibilia J, et al. Evaluation of two strategies (initial methotrexate monotherapy vs its combination with adalimumab) in management of early active rheumatoid arthritis: data from the GUEPARD trial. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1429–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruynesteyn K, Landewé R, van der Linden S, et al. Radiography as primary outcome in rheumatoid arthritis: acceptable sample sizes for trials with 3 months' follow up. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1413–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldsmith CH, Smythe HA, Helewa A. Interpretation and power of a pooled index. J Rheumatol 1993;20:575–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Heijde DM, van't Hof MA, van Riel PL, et al. Validity of single variables and composite indices for measuring disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51:177–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. The definition and measurement of disease modification in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006;32:9–44, vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Klareskog L, et al. Presentation and analysis of data on radiographic outcome in clinical trials: experience from the TEMPO study. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:49–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aletaha D, Funovits J, Breedveld FC, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis joint progression in sustained remission is determined by disease activity levels preceding the period of radiographic assessment. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:1242–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Molenaar ET, Voskuyl AE, Dinant HJ, et al. Progression of radiologic damage in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in clinical remission. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:36–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.ten Wolde S, Breedveld FC, Hermans J, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled study of stopping second-line drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 1996;347:347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Combe B, Landewe R, Lukas C, et al. Eular recommendations for the management of early arthritis: Report of a task force of the European Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:34–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:762–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions Rheumatoid arthritis: national clinical guideline for management and treatment in adults. London: Royal College of Physicians, February 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]