This work identifies a small GTPase required in barley for full penetration resistance against powdery mildew. This GTPase is associated with multivesicular bodies and is important for callose deposition, implying that this cell wall polymer may be transported to the site of attack.

Abstract

Host cell vesicle traffic is essential for the interplay between plants and microbes. ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) GTPases are required for vesicle budding, and we studied the role of these enzymes to identify important vesicle transport pathways in the plant–powdery mildew interaction. A combination of transient-induced gene silencing and transient expression of inactive forms of ARF GTPases provided evidence that barley (Hordeum vulgare) ARFA1b/1c function is important for preinvasive penetration resistance against powdery mildew, manifested by formation of a cell wall apposition, named a papilla. Mutant studies indicated that the plasma membrane–localized REQUIRED FOR MLO-SPECIFIED RESISTANCE2 (ROR2) syntaxin, also important for penetration resistance, and ARFA1b/1c function in the same vesicle transport pathway. This was substantiated by a requirement of ARFA1b/1c for ROR2 accumulation in the papilla. ARFA1b/1c is localized to multivesicular bodies, providing a functional link between ROR2 and these organelles in penetration resistance. During Blumeria graminis f sp hordei penetration attempts, ARFA1b/1c-positive multivesicular bodies assemble near the penetration site hours prior to the earliest detection of callose in papillae. Moreover, we showed that ARFA1b/1c is required for callose deposition in papillae and that the papilla structure is established independently of ARFA1b/1c. This raises the possibility that callose is loaded into papillae via multivesicular bodies, rather than being synthesized directly into this cell wall apposition.

INTRODUCTION

Powdery mildew fungi cause disease on numerous plant species and are serious threats to many crops. These obligate biotrophic fungi penetrate directly through the host epidermal cell wall and establish a haustorium inside the plant cell. The haustorium serves as a feeding structure and is essential for the biotrophic host–pathogen interaction. A plant cell–generated extrahaustorial membrane separates the haustorium from the plant cytoplasm. The nature of the membrane and the components of the vesicle trafficking pathway, leading to formation of the extrahaustorial membrane, are unknown (Koh et al., 2005; Eichmann and Hückelhoven, 2008).

Plants defend themselves against pathogen attack with a complex set of multifactorial mechanisms. These involve pathogen-associated molecular pattern–triggered immunity, often referred to as basal defense, followed by effector-triggered immunity (Jones and Dangl, 2006). Preinvasive basal defense against powdery mildew fungi is manifested at the stage of penetration by the formation of a local cell wall apposition, called a papilla. Through mutant screens in Arabidopsis thaliana, three genes have been identified representing two separate pathways essential for full preinvasive basal defense or penetration resistance. One pathway is characterized by PENETRATION2 (PEN2) and PEN3 that affect secondary metabolite secretion. PEN2 encodes a β-thioglucoside glucohydrolase, required for glucosinolate biosynthesis (Lipka et al., 2005; Bednarek et al., 2009), and PEN3 encodes a plasma membrane ABC transporter, believed to export the product of PEN2 (Stein et al., 2006). The second pathway is characterized by PEN1, encoding a syntaxin. PEN1 forms a complex with the other SNARE proteins, SNAP33 and VAMP721/722, to mediate a plasma membrane fusion process required for penetration resistance (Collins et al., 2003; Assaad et al., 2004; Kwon et al., 2008).

The PEN1 pathway has also been identified in barley (Hordeum vulgare). A suppressor mutant screen of mlo5 resistance against the barley powdery mildew fungus (Blumeria graminis f sp hordei [Bgh]) demonstrated REQUIRED FOR MLO-SPECIFIED RESISTANCE2 (ROR2) to be required for penetration resistance (Freialdenhoven et al., 1996). Cloning of ROR2 revealed that it encodes the syntaxin ortholog of PEN1, and SNAP34 was identified to be an interacting SNARE protein essential for penetration resistance (Collins et al., 2003; Douchkov et al., 2005). PEN1 and ROR2 are both localized in the plasma membrane, and during Bgh attack, these proteins accumulate strongly at the sites of penetration (Assaad et al., 2004; Bhat et al., 2005). Interestingly, this papilla accumulation occurs outside the plasma membrane (Meyer et al., 2009), and since membrane material is detected inside the papilla structure (Assaad et al., 2004; An et al., 2006b), it has been hypothesized that PEN1/ROR2 is transported to this location through intraluminal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (MVBs). These may fuse to the plasma membrane, leading to exosomes being embedded in the papilla (Meyer et al., 2009). A number of other constituents have been described in barley papillae. These include a phenolic conjugate, p-coumaroyl-hydroxyagmatine (von Röpenack et al., 1998), H2O2, cell wall cross-linked proteins (Thordal-Christensen et al., 1997), iron (Fe3+) (Liu et al., 2007), and cell wall cross-linked phenolics (Smart et al., 1986). Meanwhile, the β-1,3-glucan polymer, callose, is the most well-studied component of the papilla, and it is often used as a marker for papilla formation. The callose synthase, POWDERY MILDEW RESISTANT4 (PMR4), responsible for this particular callose deposition has been identified in Arabidopsis, and it was shown that plants lacking this polymer have a slightly decreased penetration resistance (Jacobs et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2003). This may in turn suggest that callose is one of a number of important papilla components that contribute to penetration resistance. PMR4 is predicted to be an integral membrane enzyme, localized in the plasma membrane prior to fungal attack (Jacobs et al., 2003). However, the exact mechanism(s) by which callose synthases are activated in plants to produce callose from UDP-glucose or how callose is deposited into cell walls is currently unknown (Chen and Kim, 2009). Since the structure of the papilla remains intact in the Arabidopsis pmr4 callose-negative mutant, a structural scaffold constituent must exist in addition to callose (Jacobs et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2003). However, histochemical analyses of the major cell wall constituents, cellulose and pectin, have been negative in barley (Smart et al., 1986), implying that these are not part of the papilla structure.

It is predicted that papilla and extrahaustorial membrane formation, as well as other aspects of the plant–powdery mildew fungus interaction, requires vesicle trafficking in the host cell. Vesicle budding is regulated by ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF) GTPases together with a number of associated proteins, including ARF-GTPase–activating proteins and ARF guanine nucleotide exchange factors (ARF-GEFs). In their GTP-bound active state, ARF GTPases recruit coat proteins to patches of specific membranes, whereby vesicle budding is induced. Plant ARFs group into a number of subfamilies and subgroups (Vernoud et al., 2003), but specific membrane association and biological function have only been identified for a few of these (Hwang and Robinson, 2009). In Arabidopsis, ARFB (named ARFB1a in Vernoud et al., 2003) localizes to the plasma membrane (Matheson et al., 2008), while ARF1 (named ARFA1c in Vernoud et al., 2003) localizes to the Golgi apparatus and endocytic organelles and is suggested to play a role in root hair positioning (Xu and Scheres, 2005). A tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) ARF1, closely related to Arabidopsis ARFA1c, is required for activation of pathogen defense mediated through the hypersensitive response (Coemans et al., 2008). ARF GTPase activity requires ARF-GEFs for replacing GDP with GTP. This central function regulating vesicle budding has been found to be a target for pathogens to promote disease development. Thus, it was recently found that the Pseudomonas syringae bacterial effector HopM1 specifically induces proteosomal degradation of an Arabidopsis ARF-GEF important in defense. Interestingly, this ARF-GEF, named MIN7, is also important for Pseudomonas-triggered callose deposition (Nomura et al., 2006).

In this work, barley ARFA1b/1c GTPase was identified as being required for full penetration resistance against Bgh. Our results suggest that the ROR2 syntaxin and ARFA1b/1c are functionally linked in regulating pathogen defense. ARFA1b/1c-eGFP (for enhanced green fluorescent protein) localizes to MVBs, which in Bgh-attacked cells assemble around the site of penetration 2 h prior to the earliest detected callose accumulation. Inactivation of ARFA1b/1c eliminates ROR2 and callose accumulation at the site of attack, providing molecular evidence that MVBs are required for the loading of these components into the papillae.

RESULTS

Six ARF GTPase Genes Expressed in Barley Leaf Epidermis

ARF GTPases play a key role in vesicle formation, and the role of these proteins was investigated in the Bgh–barley interaction. Through BLAST searches in the public barley EST database, http://www.plantgdb.org, we identified full-length barley EST contigs encoding 14 members of the ARF GTPase family. In Arabidopsis, the ARF GTPase protein family consists of three subfamilies (AFR, ARL, and SAR), some of which in turn are subdivided into groups (Vernoud et al., 2003). A phylogenetic analysis with the Arabidopsis ARF GTPases revealed that the 14 barley ARF GTPases clustered within these subfamilies and groups. They were subsequently named according to the Arabidopsis nomenclature (Vernoud et al., 2003) (Figure 1; see Supplemental Table 1 online). In the barley ARF subfamily, eight highly homologous members were identified. Interestingly, ARFA1b and ARFA1c encode identical proteins (see Supplemental Figure 1A online), but the coding sequences are only 93% identical at the nucleotide level.

Figure 1.

Identification of Barley ARF-GTPases.

Phylogenetic analysis of barley and Arabidopsis members of the ARF-GTPase protein family. Rooted neighbor-joining tree. Bootstrap values are shown above each branch, and the tree was collapsed when the value was below 50. The Arabidopsis (At) proteins are named as by Vernoud et al. (2003), and the barley (Hv) proteins are named accordingly. The ScYpt51p RAB5 GTPase from yeast is used as an outgroup. The alignment used to generate this tree is available as Supplemental Data Set 1 online.

Since powdery mildew infection occurs exclusively in the epidermal cell layer, we investigated which of the barley GTPase genes of the ARF subfamily are expressed in this tissue. ARFA1a, ARFA1b, ARFA1c, ARFB1b, ARFB1c, and ARFC were found to be expressed since they could be PCR amplified from a barley epidermal cell cDNA sample (see Supplemental Figure 1B online). Meanwhile, ARFA1d could not be PCR amplified from this cDNA sample, even after several attempts.

ARFA1b/1c Is Required for Full Penetration Resistance

Single cell transient-induced gene silencing (TIGS) is a highly useful method for evaluating the role of single genes in plant–powdery mildew fungal interactions, which are single host cell autonomous (Collins et al., 2003; Douchkov et al., 2005). The method is based on cotransformation of RNA interference (RNAi) constructs for the genes of interest and a visual marker construct encoding β-glucuronidase (GUS) into leaf epidermal cells, using particle bombardment. Therefore, we generated 35S promoter–driven RNAi constructs for five of the six ARF genes expressed in barley epidermis. The ARFA1b RNAi fragment showed 93% nucleotide identity to ARFA1c, including stretches of 26, 31, and 57 bps of 100% identity. We therefore considered that the ARFA1b RNAi fragment would target both genes, and the RNAi construct was named ARFA1b/1c. Since the proteins encoded by these two genes are identical, we will refer only to ARFA1b/1c hereafter. The five individual ARF GTPase RNAi constructs were cotransformed with the GUS marker construct into leaf epidermal cells of barley, cv Golden Promise. Two days after bombardment, the leaves were inoculated with a virulent isolate of Bgh, and after another 2 d, the leaves were stained for GUS activity. By subsequent microscopy, the frequency of GUS-stained epidermal cells with Bgh haustoria was assayed. Interference of ARF GTPases involved in haustoria establishment and function, such as effector secretion, would result in a lower occurrence of haustoria, seen as increased resistance. Alternatively, interference of ARF GTPases involved in transport of defense components related to penetration resistance would result in a higher haustorial occurrence. The TIGS experiment revealed that none of the ARF RNAi constructs caused increased resistance against Bgh. Instead, the ARFA1b/1c RNAi construct caused a 2-fold increase in the frequency of cells with haustoria compared with the empty vector control (Figure 2A). This indicates that ARFA1b/1c is involved in penetration resistance, and further examinations were focused on this ARF GTPase.

Figure 2.

Identification and Expression Analysis of a Barley ARF GTPase Involved in Penetration Resistance against Bgh.

(A) Relative haustorial index after transformation with the indicated 35S-driven ARF RNAi constructs.

(B) Relative haustorial index after transformation with constructs for 35S-driven expression of wild-type or mutant versions of ARFA1b/1c.

(A) and (B) The constructs were cotransformed with a GUS reporter construct into barley epidermal tissue, followed by inoculation with Bgh 2 d after bombardment. Haustorial indices (number of cells with haustoria divided by total number of cells) of GUS-stained, transformed epidermal cells was determined 48 HAI by light microscopy. The indices are given relative to empty vector controls.

(C) Transcript levels of ARF genes in whole leaves during Bgh infection, detected by quantitative PCR. ARF transcripts were normalized to GAPDH. Time point 0 was set to 1.

Data shown are mean values; n = 6 (A) and 3 ([B] and [C]). Error bars are ±sd.

The high nucleotide sequence identity between the barley ARF subfamily transcripts expressed in the epidermis suggests the possibility of cross-silencing genes other than ARFA1b/ARFA1c. As indicated in Supplemental Figure 1C online, ARFA1a shares an identical 24-nucleotide stretch with ARFA1b and an identical 30-nucleotide stretch with AFRA1c. ARFA1b/1c RNAi resulted in increased penetration (Figure 2A). Therefore, the minor effect on penetration of the ARFA1a RNAi (Figure 2A) could potentially be due to cross-silencing of these two transcripts. BLAST searches did not uncover potential off-targets outside the ARF subfamily.

To confirm the ARFA1b/1c RNAi result, we exploited the fact that the specific amino acid substitutions T31N and Q71L can be used to interfere with the activity of endogenous ARF GTPase. The T31N substitution causes low affinity for GTP; therefore, the protein behaves as a GDP-locked enzyme, whereas the Q71L substitution eliminates the GTPase activity, resulting in a GTP-locked enzyme (Dascher and Balch, 1994; Pepperkok et al., 2000). These amino acids are conserved within the barley ARF GTPase subfamily (see Supplemental Figure 1A online); thus, it can be expected that expression of ARFA1b/1c-T31N and ARFA1b/1c-Q71L will specifically hamper the function of the endogenous ARFA1b/1c, as previously demonstrated for other ARF GTPases (Takeuchi et al., 2002; Xu and Scheres, 2005). The ARFA1b/1c-T31N GDP-locked enzyme will sequester the corresponding ARF-GEF and therefore function as a dominant-negative protein (Dascher and Balch, 1994). The ARFA1b/1c-Q71L GTP-locked version will also function negatively because ARF-GTPase and coat release from the budding vesicle requires hydrolysis of the bound GTP to GDP (East and Kahn, 2010). Biolistic transformation of 35S promoter–driven constructs, encoding ARFA1b/1c (wt), ARFA1b/1c-T31N, and ARFA1b/1c-Q71L, were conducted with the same experimental setup as the TIGS analysis above. Both the T31N and the Q71L mutant forms of ARFA1b/1c increased penetration (Figure 2B), confirming the ARFA1b/1c RNAi result. Interestingly, transient expression of ARFA1b/1c (wt) resulted in a reduction of the relative haustorial index to 0.57 (Figure 2B).

The reduced penetration caused by expression of ARFA1b/1c (wt) (Figure 2B) suggests that the endogenous ARFA1b/1c could be insufficient for full penetration resistance due to specific fungal influence on the encoding transcripts. To explore this possibility, the levels of the ARF transcripts were analyzed in leaves during Bgh attack. In general, Bgh had limited impact on these transcript levels (Figure 2C). However, the levels of the ARFA1a and particularly of the ARFA1b transcript showed interesting patterns. The ARFA1a transcript was temporarily increased to 3 times the basal level at 8 h after inoculation (HAI), which is the time when the papilla formation at the penetration site is initiated (see below). Meanwhile, the ARFA1b transcript level remained unchanged during the initial stages of infection, 0 to 8 HAI. However, a relative transcript decrease to 0.4 occurred between 8 and 16 HAI, lasting throughout the experiment. This ARFA1b transcript decrease coincided with the time point of penetration at 10 to 12 HAI (Zeyen et al., 2002; Eichmann and Hückelhoven, 2008). This transcript decrease might therefore be counteracted by constitutive expression of ARFA1b/1c, which reestablishes the GTPase activity level (Figure 2B).

To rule out the possibility that interference with ARFA1b/1c affected cell vitality, we compared the number of GUS cells occurring after cotransformation with the empty vector to the number occurring after cotransformation with the ARFA1b/1c RNAi, ARFA1b-T31N, ARFA1b-Q71L, and ARFA1b (wt) constructs. No deviations in the GUS cell numbers were noted, verifying that these cells are still viable 4 d after transformation. Moreover, haustoria developed normally in transformed cells, indicating that vesicle trafficking processes important for Bgh growth remained unaffected. This includes formation of the extrahaustorial membrane, believed to be a prerequisite for haustorial formation (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Taken together, this suggests that the Bgh-associated function of ARFA1b/1c is limited to mediating penetration resistance.

ARFA1b/1c Is Required for ROR2-Mediated Penetration Resistance

The barley mutation ror2 was originally found to reduce penetration resistance in mlo powdery mildew–resistant Ingrid (Freialdenhoven et al., 1996). However, even MLO-susceptible barley has an intermediate level of penetration resistance, which is also hampered by ror2 mutation (Collins et al., 2003). Since the mutation in ROR2 and interference with ARFA1b/1c both result in increased haustoria formation, and since both are associated with vesicle trafficking, we speculated that these two components could be functionally linked. To verify this hypothesis, the ror2 mutant (MLO wt) and the corresponding wild-type cultivar, Ingrid, were transformed with the ARFA1b-T31N construct, and the impact on haustoria frequency was assayed. In Ingrid, transformation of ARFA1b-T31N caused the frequency of haustoria-containing cells to increase 2.5-fold (Figure 3), confirming the results obtained in Golden Promise (Figure 2B). Furthermore, the number of cells with haustoria in ror2 was 2.5-fold higher than in the wild type after transformation with the empty vector control construct. Finding this effect of the ror2 allele, also in the absence of the mlo mutation, is in line with the previous results obtained using segregating genetic material (Collins et al., 2003), suggesting that ROR2, like PEN1, is required for preinvasive basal defense. Importantly, transformation of ror2 with the ARFA1b-T31N construct had no additional effect on the frequency of cells with haustoria (Figure 3), implying that ROR2 and ARFA1b/1c act on the same pathway. To rule out the possibility that a penetration maximum already is reached in ror2 and that this is the reason why no further increase in cells with haustoria was observed after transformation with ARFA1b-T31N, we silenced polyubiquitin, previously found to dramatically affect penetration resistance in barley (Dong et al., 2006). The polyubiquitin RNAi construct increased the frequency of cells with haustoria in ror2 by 2.7-fold, showing that a penetration maximum had not been reached (Figure 3). In summary, these results indicated that ROR2 and ARFA1b/1c function in the same membrane trafficking pathway ultimately resulting in penetration resistance.

Figure 3.

ARFA1b/1c-GTPase and ROR2 Syntaxin Act on the Same Pathway Mediating Penetration Resistance.

Impact on relative haustorial index (see legend for Figure 2) of transformation of barley cultivar Ingrid wild type (wt) and ror2 with ARFA1b-T31N. The construct was cotransformed with a GUS reporter construct into barley epidermal cells, followed by inoculation with Bgh 2 d later. Haustoria frequency of GUS-stained, transformed epidermal cells was determined 48 HAI by light microscopy. The empty vector was used as reference. A polyubiquitin RNAi construct was used as positive control. Data shown are mean values; n = 3. Error bars are ±sd.

ARFA1b/1c Is Essential for ROR2 Accumulation in Papillae

It has previously been demonstrated that ROR2 accumulates in papillae at sites where Bgh appressoria attempt to penetrate (Bhat et al., 2005). Since our data suggest that ARFA1b/1c is required for ROR2-mediated penetration resistance, we were interested in understanding how ARFA1b/1c and ROR2 are interconnected. We therefore examined how ARFA1b/1c influenced the localization of ROR2 in barley epidermal cells transiently expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-ROR2. Figure 4A shows plasma membrane localization of YFP-ROR2, as previously shown by Bhat et al. (2005). In cells cotransformed with either the ARFA1b-T31N or the ARFA1b-Q71L construct, YFP-ROR2 localized to the plasma membrane and to body-like structures (Figures 4B and 4C). In response to Bgh attack, focal accumulation of YFP-ROR2 occurred in papillae (Bhat et al., 2005; Figures 4D to 4F). Interestingly, this focal accumulation was inhibited when the ARFA1b-T31N or the ARFA1b-Q71L construct was introduced together with the YFP-ROR2 construct (Figures 4G to 4L). Instead, the YFP-ROR2 signal accumulated in body-like structures of variable sizes at multiple locations throughout the cell. Although the density of these YFP-ROR2 positive bodies was higher near the sites of penetration, we never observed YFP-ROR2 signal in papillae (Figures 4G to 4L). Moreover, during Bgh attack, YFP-ROR2 appeared to be internalized from the plasma membrane (Figures 4D to 4L), suggesting that the papilla-localized YFP-ROR2 is derived from the entire plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

ARFA1b/1c Function Is Required for ROR2 Localization to Bgh-Induced Papillae.

(A) to (C) Localization analysis of transiently expressed YFP-ROR2 in noninoculated barley epidermal cells 24 h after transformation with 35S:YFP-ROR2 (A), cotransformation with 35S:YFP-ROR2 and 35S:ARFA1b-Q71L (B), or cotransformation with 35S:YFP-ROR2 and 35S:ARFA1b-T31N (C).

(D) to (L) Localization analysis of transiently expressed YFP-ROR2 in barley epidermal cells, 12 to 14 HAI with Bgh. Transformation with 35S:YFP-ROR2 ([D] to [F]), cotransformation with 35S:YFP-ROR2 and 35S:ARFA1b-Q71L ([G] to [I]), and cotransformation with 35S:YFP-ROR2 and 35S:ARFA1b-T31N ([J] to [L]). YFP fluorescence images ([D], [G], and [J]) and bright-field images ([E], [H], and [K]) are merged in (F), (I), and (L). YFP-ROR2 localization magnified three times in inserts. Arrows indicate sites of Bgh attack.

Bars = 10 μm.

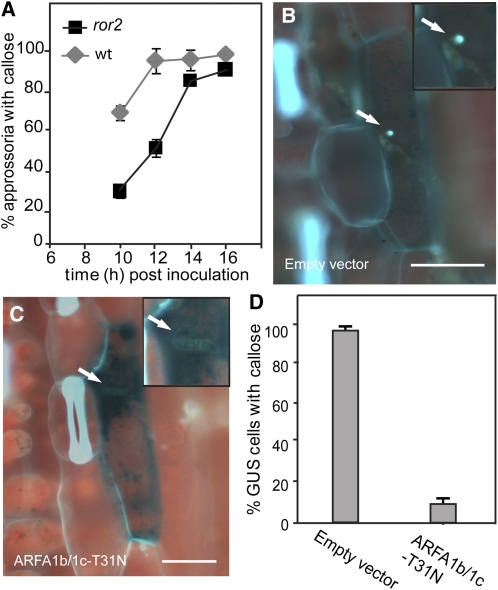

Callose Timing Is Dependent on ROR2, While Callose Deposition Is Dependent on ARFA1b/1c

In Arabidopsis, the involvement of the ROR2 ortholog PEN1 in penetration resistance can be explained by the fact that it is required for timely formation of papillae, visualized by a delayed callose deposition in the Bgh appressoria-induced papillae of pen1 mutants (Assaad et al., 2004). To verify that the ROR2 syntaxin has the same involvement in callose accumulation in barley, we compared the timing of callose deposition at Bgh penetration sites in the ror2 mutant and in Ingrid (wt). This revealed that, similar to pen1, callose deposition is delayed by 3 h in ror2 at the time of penetration (i.e., 10 to 12 HAI; Figure 5A) and confirmed that ROR2 also is required for timely deposition of callose.

Figure 5.

Callose Timing Is Dependent on ROR2, Whereas Callose Deposition Is Dependent on ARFA1b/1c.

(A) Callose deposition in response to Bgh is delayed by mutation in ROR2. Leaves of barley cultivar Ingrid wild type (wt) and ror2 were inoculated with Bgh and at various time points assayed for callose deposition at appressorial attack sites.

(B) to (D) Callose depositions in response to Bgh (18 HAI), magnified three times in inserts, after cotransformation of the GUS reporter construct with the empty vector (B) or with 35S:ARFA1b-T31N (C). Quantification of callose deposition in GUS-positive cells after cotransformation with 35S:ARFA1b-T31N or the empty vector (D).

Data shown in (A) and (D) are mean values; n = 3. Error bars are ±sd. Bars = 20 μm.

The results obtained so far suggest that ARFA1b/1c function is required for the ROR2 pathway. Therefore, we analyzed whether the role of ARFA1b/1c in penetration resistance could be associated with Bgh-induced callose deposition. Transformation with ARFA1b-T31N reduced the number of cells showing callose deposition to only 8% compared with 97% of the cells transformed with the empty vector (Figures 5B to 5D). This result is strong evidence for ARFA1b/1c being essential for callose deposition in papillae. Inserts in Figures 5B and 5C illustrate at high magnification the differential callose response at Bgh penetration sites.

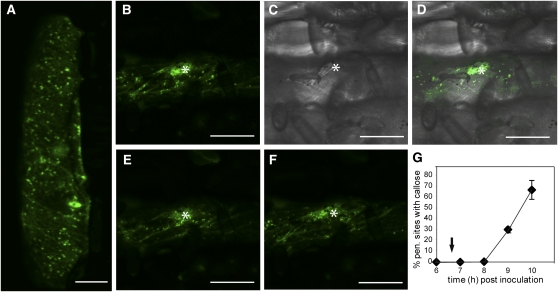

ARFA1b/1c Localization Near Penetration Sites Prior to the Appearance of Callose

The observation that ARFA1b/1c is required for penetration resistance and callose loading into papillae led us to unravel ARFA1b/1c’s subcellular localization. We generated a C-terminal fusion construct of ARFA1b/1c and eGFP under the control of the 35S promoter. To verify that this fusion protein is biologically functional, we assayed the frequency of cells with Bgh haustoria after transformation with 35S:ARFA1b-eGFP. An increased level of penetration resistance was observed (see Supplemental Figure 3A online) equivalent to the level of resistance obtained after overexpression of ARFA1b/1c (Figure 2B). In noninoculated barley epidermal cells transiently expressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP, the GFP signal is localized to multiple, mobile organelles (Figure 6A). Subsequently, we wanted to study whether this localization pattern was influenced by fungal attack. Thus, leaves were inoculated with Bgh 24 h after transformation with the ARFA1b-eGFP construct. At 6 to 7 HAI, an assembly of GFP-positive organelles near the penetration sites was observed (Figures 6B to 6D). From images taken of the same attack site, at 5-min intervals, it became apparent that these GFP-positive organelles were highly mobile. At each time point, the distribution of the GFP-positive organelles changed and was accompanied by an increased density near the site of attack (Figures 6E and 6F). These assemblies could be observed until 18 HAI, when the experiment was terminated (see Supplemental Figures 3B to 3G online).

Figure 6.

ARFA1b/1c Organelles Are Recruited to the Penetration Site Prior to Callose Deposition.

(A) Localization analysis of transiently expressed ARFA1b-eGFP in noninoculated barley epidermal cells.

(B) to (F) Localization of ARFA1b/1c-eGFP–positive organelles at Bgh appressorial attack sites 6 to 7 HAI (asterisks). Barley epidermal cells were inoculated 24 h after bombardment with ARFA1b-eGFP. GFP fluorescence image (B) and bright-field image (C) are merged in (D). GFP fluorescence images ([E] and [F]) were taken 5 and 10 min later than (B), respectively.

(G) Quantification of callose deposition at Bgh appressorial attack sites in untransformed cells of the leaves studied in (B) to (F). Arrow indicates the first observation of ARFA1b/1c-eGFP–positive organelle assembly. Data shown are mean values; n = 3. Error bars are ±sd.

Bars = 10 μm.

Callose deposition in papillae is an early response to penetration attempts (Eichmann and Hückelhoven, 2008), and in Ingrid (wt), callose accumulation was detected at ~70% of the attack sites at 10 HAI (Figure 5A). To study the timing of callose deposition relative to ARFA1b/1c assembly at Bgh appressoria penetration sites, the same Golden Promise leaf material that was assayed for ARFA1b/1c localization (Figures 6B to 6F) was used in a time-course experiment for callose detection (Figure 6G). Callose deposition could not be detected between 6 and 8 HAI. However, at 9 HAI, 30% of the appressoria had Bgh-induced callose accumulation (Figure 6G). The timing of these deposits in untransformed wild-type cells indicated that the ARFA1b/1c assembly at 6 to 7 HAI precedes callose deposition by at least 2 h. Overexpression of ARFA1b/1c-eGFP, leading to increased penetration resistance, could be envisioned to result in an earlier deposition of callose. Therefore, we compared the timing of this papilla marker in GUS cells cotransformed with constructs for ARFA1b/1c-eGFP or eGFP. However, the appearance of callose in neither of these cells types deviated from the result in untransformed cells (Figure 6G; see Supplemental Figure 3H online).

ARFA1b/1c Is Localized to the ARA7 Endosomal Compartment

To obtain further understanding of ARFA1b/1c’s role in penetration resistance, we explored the intracellular localization in more detail. For this purpose, onion epidermal cells were transformed with ARFA1b-eGFP using particle bombardment. The fluorescent signal was localized to small mobile organelles (Figure 7A) as previously observed in barley epidermal cells (Figure 6A). To determine the origin of these organelles, onion epidermal cells expressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP were incubated with FM4-64 for 45 min. FM4-64 is a fluorescent marker that binds to the plasma membrane and is internalized by endocytosis. The GFP fluorescent organelles partially coincided with FM4-64 signal (Figures 7B and 7C), indicating that ARFA1b/1c is located in endocytic organelles. The fungal toxin brefeldin A (BFA) is commonly used as an inhibitor of vesicle budding, where it inhibits the function of sensitive ARF-GEFs, resulting in endosomal aggregations referred to as BFA bodies. To investigate if ARFA1b/1c localization is sensitive to BFA, FM4-64–incubated onion epidermal cells, expressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP, were treated with BFA. After only 5 min of BFA treatment, both ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and FM4-64–labeled organelles were affected, and prolonged treatment resulted in coaggregation of ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and FM4-64 in BFA bodies (Figures 7D to 7F). This subcellular localization of ARFA1b/1c-eGFP resembles the localization of ARA7 (Jaillais et al., 2008), a plant RAB5 GTPase homolog shown to be a marker for MVBs (Lee et al., 2004; Haas et al., 2007). We therefore investigated if ARFA1b/1c and ARA7 colocalized in onion epidermal cells coexpressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and red fluorescent protein (RFP)-AtARA7. This revealed that the ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and RFP-AtARA7 signals colocalized (Figures 7G to 7I). To confirm that ARFA1b/1c is localized to this cellular compartment in barley, Golden Promise was cotransformed with ARFA1b-eGFP and RFP-AtARA7. In epidermal cells, ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and RFP-ARA7 fluorescent signals were colocalized to the same organelles (Figures 7J to 7L). Taken together, these results indicated that ARFA1b/1c is located at MVBs.

Figure 7.

Localization of Barley ARFA1b/1c in Onion and Barley Epidermal Cells.

(A) to (C) Colocalization analysis in onion epidermis transiently expressing barley ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and treated with 5 μM FM4-64 for 45 min. GFP fluorescence image (A) and FM4-64 fluorescence image (B) are merged in (C). Inserts are magnified parts of (A) to (C).

(D) to (F) Colocalization analysis in onion epidermis transiently expressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and treated with 5 μM FM4-64 for 45 min and 100 μM BFA for 25 min. GFP fluorescence image (D) and FM4-64 fluorescence image (E) are merged in (F).

(G) to (I) Colocalization analysis in onion epidermis transiently coexpressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and RFP-AtARA7. GFP fluorescence image (G) and RFP fluorescence image (H) are merged in (I).

(J) to (L) Colocalization analysis in barley epidermis transiently coexpressing ARFA1b/1c-eGFP and RFP-AtARA7. GFP fluorescence image (J) and RFP fluorescence image (K) are merged in (L).

Bars = 10 μM (3 μM in insets).

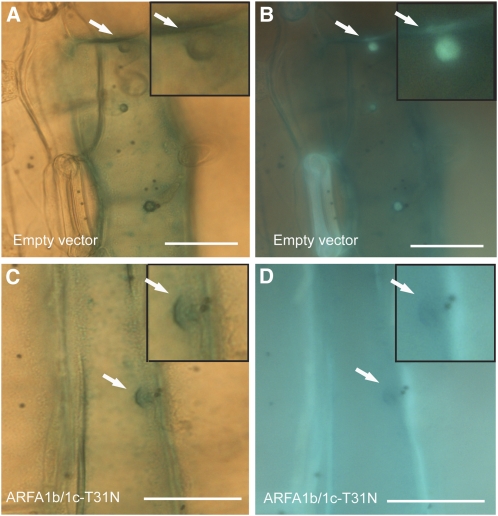

Papilla Structure Forms Independently of MVB-Associated ARFA1b/1c

It has previously been demonstrated that the papilla structure is present, although callose is not formed in Arabidopsis pmr4 in response to powdery mildew fungal attack (Jacobs et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2003). Having obtained evidence that the MVB-localized ARFA1b/1c is required for penetration resistance and papilla callose deposition (Figures 5C and 5D), it was relevant to investigate whether formation of the papilla structure also depends on ARFA1b/1c function. We therefore determined the presence of papilla structure 48 HAI with Bgh in cells transformed either with the empty vector or ARFA1b-T31N. In empty vector control cells, the papilla structure was clearly formed in response to Bgh, always with detectable levels of callose (Figures 8A and 8B). However, in barley cells transformed with ARFA1b-T31N, the papilla structure was present (Figure 8C), despite absence of callose (Figure 8D). Since callose inevitably occurs in papillae in wild-type cells, absence of callose could be used as an indicator of ARFA1b/1c inactivation. This finding that the papilla structure is formed in ARFA1b-T31N transformed cells indicated that, unlike the callose deposition, papilla formation per se does not require ARFA1b/1c function. Furthermore, this suggests that callose may be loaded into the papilla structure via ARFA1b/1c-positive MVBs.

Figure 8.

ARFA1b-T31N Affects Only Callose Deposition, Not the Papilla Structure.

(A) and (B) Barley epidermal cell cotransformed with the empty vector and a GUS reporter construct shown 48 h after Bgh inoculation.

(C) and (D) Barley epidermal cell cotransformed with a 35S:ARFA1b-T31N and a GUS reporter construct shown 48 h after Bgh inoculation.

Bright-field images of papilla structure (arrows) shown in (A) and (C). Fluorescence images of callose deposition (arrows) shown in (B) and (D). Magnified papillae shown in insets. Bars = 20 μm.

DISCUSSION

The preinvasive basal defense pathway, characterized by ROR2/PEN1 syntaxin, contributes significantly to preventing Bgh from entering barley epidermal cells. Besides identification of syntaxin-interacting SNARE partners, which together with ROR2/PEN1 mediate membrane fusion events at the plasma membrane, little is known of other components in this pathway. We performed TIGS of five ARF GTPases expressed in barley epidermal cells and obtained evidence that barley ARFA1b/1c is required for penetration resistance against powdery mildew. During powdery mildew attack, a number of additional plant processes are predicted to involve vesicle trafficking. These include extrahaustorial membrane initiation, formation, and function. The TIGS experiments did not provide evidence for involvement of any of the studied ARF-GTPases in such processes. The TIGS result for ARFA1b/1c was further confirmed by expression of ARFA1b/1c-T31N and ARFA1b/1c-Q71L mutant proteins after which the cells became even more susceptible to Bgh. We speculate that this difference reflects that expression of the mutant proteins is more efficient in interfering with endogenous ARFA1b/1c-dependent vesicle formation than RNAi silencing, where even low levels of ARFA1b and ARFA1c transcripts may contribute to maintaining some degree of penetration resistance. This can be the case particularly because the ARFA1b and ARFA1c nucleotide sequences are not identical, making the ARFA1b-based RNAi construct potentially less efficient in targeting the ARFA1c transcript. To analyze if ARFA1b/1c and ROR2 are functionally related, ARFA1b/1c-T31N was expressed in epidermal cells of ror2. This did not cause an increase in the frequency of Bgh haustoria, which was otherwise observed in Ingrid (wt). This suggests that ARFA1b/1c-T31N targeted a vesicle traffic pathway that was already hampered in ror2, indicating that ROR2 and ARFA1b/1c are functionally linked.

The link between ARFA1b/1c and ROR2 was further substantiated by our finding that relocalization of YFP-ROR2 required ARFA1b/1c function. ROR2 is known to accumulate strongly in the papillae, where the fungus attempts to penetrate (Bhat et al., 2005). However, transformation with either ARFA1b-T31N or ARFA1b-Q71L inhibited YFP-ROR2 papilla localization, and instead YFP-ROR2 accumulated in body-like structures. ARFA1b/1c-eGFP colocalized with ARA7 in barley as well as in onion epidermal cells, and since ARA7 has been shown to localize to MVBs (Lee et al., 2004; Haas et al., 2007), we suggest that ARFA1b/1c is playing a role in vesicle budding from MVBs (see below). In turn, this budding event is important for penetration resistance and ROR2 localization in papillae. This and the assembly of ARFA1b/1c-positive MVBs near the penetration sites indicate a functional link between MVBs and full penetration resistance and between MVBs and papilla localization of ROR2. Such a role of MVBs is in agreement with electron microscopy analyses showing apoplastic vesicles at sites of Bgh penetration attempts in barley epidermal cells (An et al., 2006b). Moreover, our results support that Arabidopsis papilla body GFP-PEN1 is located on exosomes, derived from a MVB fusion at the plasma membrane as previously hypothesized by Meyer et al. (2009).

MVBs are most often described as fusing with lytic vacuoles in which proteins internalized from the plasma membrane are degraded (Davies et al., 2009). Linking MVBs to penetration resistance and to the introduction of components such as ROR2 and callose (see below) into the papilla suggests that a fusion event occurs between MVBs and the plasma membrane. This phenomenon is well known in animal cells as a means of cell-to-cell communication (Théry et al., 2009). However, the exact membrane trafficking processes required to conduct MVB/plasma membrane fusion remain unknown. It can be anticipated that those processes are similar to the more thoroughly investigated fusion between MVBs and lytic vacuoles, which just like other membrane fusion events, is mediated by a specific set of SNARE proteins, RAB effectors, and RAB GTPases (Luzio et al., 2009). MVB/plasma membrane fusion can therefore be predicted to involve a corresponding set of mediators, which make it possible for the plant cell to direct defense compounds to the papillae. The ROR2 syntaxin is potentially involved in this fusion process. The Arabidopsis ortholog PEN1 has previously been suggested to mediate fusion at the plasma membrane (Kwon et al., 2008). We demonstrated that mutation of ROR2 caused a delay in callose deposition in Bgh-induced papillae. This phenotype can explain the reduced penetration resistance of ror2, as previously suggested for pen1 in Arabidopsis (Assaad et al., 2004). On the other hand, we discovered that ARFA1b/1c function was required for callose deposition into papillae of attacked barley cells. This suggests that the ROR2 syntaxin can be replaced by another syntaxin, albeit less efficiently, whereas the function of ARFA1b/1c in penetration resistance cannot be taken over by another of the ARF GTPases. However, a direct role of ARFA1b/1c in this process is not obvious, as secretion of exosomes hardly involves formation of coated pits and vesicles. Therefore, we envision that the ARFA1b/1c-GTPase mediates formation of ARA7 MVB-derived vesicles with another destination, potentially in retrograde trafficking. Interference with this trafficking could negatively affect MVB function, resulting in the reduced penetration resistance that we observe.

Whereas we provide some molecular evidence for a biological role of MVBs, there has for many years been good evidence based on electron microscopy that MVB/plasma membrane fusion and secretion of exosomes occur in plants (An et al., 2007). Besides association with pathogen-induced papilla formation, it appears to occur during cytokinesis where cell plates are formed (Lehmann and Schulz, 1969; Samuels et al., 1995), in association with plasmodesmata (An et al., 2006a), and during phloem sieve plate formation (Evert and Eichhorn, 1976). Interestingly, these are also sites where callose deposition occurs. Furthermore, MVBs and exosomes have been implicated in the release of viral particles from plant cells (Wei et al., 2009), and exosomes found in apoplast fluid in seeds have been purified and chemically characterized (Regente et al., 2009).

In Arabidopsis, pathogen-induced callose is synthesized by the callose synthase, PMR4, believed to be a plasma membrane integral enzyme, using cytosolic UDP-glucose as substrate (Jacobs et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2003). However, the exact mechanism of how callose accumulates in the papilla or in the cell wall during wounding is currently not fully understood (Chen and Kim, 2009). Our observations provide new insight to this process. First, we discovered that the function of the MVB-localized ARFA1b/1c-GTPase was required for callose accumulation in papillae. Secondly, these MVBs assemble 2 h prior to the first detectable callose at sites of Bgh attack. Together, these results suggest that callose synthase is transported by MVBs from the plasma membrane to the papilla, that callose is synthesized in MVBs, or that callose is produced at the plasma membrane and transported to the papillae by MVBs. The latter alternative is supported by a study of broad bean (Vicia faba), in which callose has been associated with MVBs in fungal defense. Electron microscopy indicated that callose was internalized by endocytosis into clathrin-coated vesicles that sorted into MVBs. Callose could subsequently be detected in the space between intraluminal vesicles inside MVBs next to attack sites (Xu and Mendgen, 1994). Even though An et al. (2006b) could not detect presence of callose in vesicles and MVBs, we believe that a general model for callose loading into papillae is emerging: Plasma membrane callose synthases, orthologous to PMR4, synthesize callose on the outside of the plasma membrane. Callose is internalized into vesicles that sort into MVBs. These MVBs are subsequently transported to the sites of attack, where they fuse with the plasma membrane. Since callose synthase is suggested to be localized to the plasma membrane constitutively (Jacobs et al., 2003), activation of this enzyme in the entire or a large part of the cell surface, followed by MVB-based relocalization of callose to the penetration site, would provide a highly efficient and rapid transport mechanism for moving large amounts of callose into cell wall structures such as the papilla. Indeed, YFP-ROR2 disappeared completely from the cell periphery during Bgh attack, and our indications that ROR2 and callose both follow a MVB ARFA1b/1c-dependent vesicle transport pathway to the papilla support this model. Interestingly, Jacobs et al. (2003) and Nishimura et al. (2003) showed that PMR4 also is essential for callose formation after wounding, and a similar vesicle transport pathway can be envisioned to be involved. It will be interesting to follow whether future research can provide more direct evidence for this model.

Callose in Arabidopsis papilla has been found to play only a minor role in penetration resistance against Bgh (Jacobs et al., 2003), and we envision a limited importance in barley as well. Therefore, it is unlikely that the absence of callose alone can explain the high frequency of haustoria in barley epidermal cells expressing ARFA1b/1c-Q71L or ARFA1b/1c-T31N. This would suggest that one or more MVB-dependent components involved in interference with penetration have yet to be discovered. It is noteworthy that an intact MVB function is not required for the formation of the papillary scaffold and that this structure apparently has minor significance for penetration resistance. Our data reveal that an opaque papilla structure is still visible despite the fact that no callose is transported to it after ARFA1b/1c-T31N expression. A similar observation was made in pmr4, where the papilla structure was formed in the absence of callose (Jacobs et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2003). The opaque appearance of papillae has been suggested to be due to significant deposition of silicon (Zeyen et al., 2002). Future studies are required to provide additional molecular tools to decipher which known or unknown papilla constituents are transported into the papilla through the ROR2 syntaxin/MVB pathway.

Our intriguing finding that barley has two genes that encode 100% identical ARF-GTPases led us to consider why this has been maintained through evolution. We investigated ARF genes in fully sequenced plant genomes, and we found that Arabidopsis, rice, and Brachypodium also have gene pairs that encode 100% identical ARF-GTPases (At1g23490 [ARFA1a]/At1g70490 [ARFA1d], Os03g59740/Os07g12170, and Bd1g53870/Bd2g53077). Strikingly, the Brachypodium pair encodes an ARF-GTPase that in turn is 100% identical to barley ARFA1b/1c, consistent with the recent separation of these two Poaceae species. These sequences deviate from both the Arabidopsis and the rice ARF-GTPases in four amino acids. Having observed that Bgh attack negatively affected the level of the ARFA1b, but not of the ARFA1c transcript, it could be speculated that there is an evolutionary benefit for plants to maintain both genes. A host species with only one gene would be more vulnerable to pathogen effectors targeting the expression of this important gene in defense.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Barley (Hordeum vulgare) seedlings cv Golden Promise were used for amplification of ARF cDNA, expression analysis, localization studies, callose staining, and determination of the role of ARF-GTPases in penetration resistance by RNAi or by overexpression of ARFA1b/1c, ARFA1b/1c-T31N, and ARFA1b/1c-Q71L. For studies of the role ARFA1b/1c in relation to ROR2, cv Ingrid carrying the ror2-1 mutant allele (Collins et al., 2003) was used and compared with the wild-type cv Ingrid. All plants were grown in climate chamber (16 h light/8 h dark) at 23°C. Blumeria graminis f. sp hordei (Bgh), isolate A6, was maintained on the barley line P-01 at 20°C (16 h light/8 h dark) using weekly inoculum transfer. Onion (Allium cepa) bulbs were purchased at the local supermarket.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Sequences of barley ARF-GTPase family members were identified by BLAST searches at http://www.plantgdb.org. Multiple alignments were generated with ClustalW at http://align.genome.jp using default settings (Thompson et al., 1994). A phylogenetic analysis was performed using the MEGA4 program with the neighbor-joining algorithm (Tamura et al., 2007). Bootstrapping was performed with 1000 replications. Evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the data set. Accession numbers and allocated gene names are shown in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Amplification of ARF-GTPase Coding Sequences and Preparation of ARF-GTPase RNAi Constructs

RNA was extracted from abaxial epidermal tissue of 7-d-old-barley leaves using the Aurum Total RNA kit (Bio-Rad). cDNA synthesis was performed using the DyNAmo cDNA synthesis kit (Finnzymes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. ARF GTPase coding sequences were PCR amplified using the CDS primers (see Supplemental Table 2 online) and 4 ng of epidermal cDNA over 33 cycles to ensure amplification of low-level transcripts (annealing at 55°C). The PCR products were confirmed by sequencing. For the RNAi constructs, regions that showed low similarity to other barley ARF genes were PCR amplified using the RNAi primers (see Supplemental Table 2 online). As an exception, the selected RNAi fragment for ARFA1b had 93% identity to ARFA1c, including three stretches of 26, 31, and 57 bp of 100% identity (see Supplemental Figure 1C online). We therefore consider the RNAi fragment for ARFA1b to target both genes. The reverse primers contain a 5′-CACC-3′ site for directional TOPO cloning. ARF RNAi constructs were obtained by cloning the PCR-amplified RNAi fragment in antisense orientation into pENTR/D according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). The Ubq RNAi construct was generated from a polyubiquitin EST sequence in the pDNR-LIB vector (BD Biosciences). The EST was derived from the same gene as HO13K06 used by Dong et al. (2006). A PCR fragment of this polyubiquitin sequence, amplified using a gene-specific (Hv Ubq) and a vector-specific primer (Universal forward) (see Supplemental Table 2 online), was inserted into the entry vector pIPKTA38 according to Douchkov et al. (2005). This Ubi RNAi fragment and the ARF RNAi fragments in pENTR/D were recombined, using LR clonase reactions according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen), into the 35S-driven destination vector pIPKTA30N (Douchkov et al., 2005, provided by Patrick Schweizer (Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben, Germany), to generate the final RNAi constructs. pIPKTA30N was used as empty vector control in the RNAi experiments.

Cloning of ARFA1b and Construct Preparations

The coding sequence of ARFA1b was amplified from barley epidermal cDNA using the cDNA primers (see Supplemental Table 2 online). The forward and reverse primers contained 5′ attB1 and attB2 sites, respectively. The ARFA1b amplified fragment was recombined into in the entry vector, pDONR201, using BP clonase (Invitrogen). The T31N and Q71L forms of ARFA1b were created by site-directed mutagenesis of the ARFA1b entry plasmid using the Quickchange XL kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Stratagene). For overexpression analysis, a destination vector, p2WF7HB, was generated from p2GWF7 (Karimi et al., 2002) by removal of the GFP coding region by religation after an AleI-SacII digestion. The ARFA1b, ARFA1b-T31N, and ARFA1b-Q71L inserts were moved from pDONR201 to p2WF7HB by an LR clonase (Invitrogen) reaction to create the final 35S-driven constructs. p2WF7HB was used as empty vector control in the overexpression analyses. The 35S:ARFA1b-eGFP construct was created with the same strategy, with the exception that the ARF stop codon was removed using a modified reverse primer in the initial PCR reaction and that the final destination vector was p2GWF7. The 35S:RFP-AtARA7 was constructed from a PCR amplification of ARA7 from Arabidopsis thaliana cDNA. The forward primer contains a 5′-CACC-3′ site for directional TOPO cloning into pENTR/D, which was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online. The 35S:RFP-AtARA7 construct was obtained by recombining the ARA7 fragment into the destination vector p2RGW7 (Karimi et al., 2002) using an LR clonase reaction. All cloning was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen). The YFP-ROR2 transient expression construct (Bhat et al., 2005) was provided by Ralph Panstruga (Max Planck Institute, Cologne, Germany).

Particle Bombardment of Gene Constructs

Transformation of gene constructs into adaxial barley first leaf and onion bulb epidermal cells was conducted by particle bombardment essentially as described by Douchkov et al. (2005). Specifically, 7 μg of the different plasmid constructs were coated onto 1-μm gold particles (Bio-Rad) using 0.5 mM Ca(NO3)2 and 10 mM spermidine. Seven-day-old barley seedlings were used for particle bombardment via the Bio-Rad PDS-1000/He particle delivery system, mounted with a hepta-adapter, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Assessment of Effect of Gene Constructs on Penetration Resistance

For experiments investigating the role of genes in penetration resistance, constructs were cobombarded with a GUS reporter construct (pUbiGUS; Douchkov et al., 2005; provided by Patrick Schweizer), followed by inoculation with Bgh (virulent isolate A6) 2 d later. Inoculation densities were between 180 and 240 conidia mm−2. GUS staining was performed overnight from 48 HAI according to Douchkov et al. (2005), followed by treatment in 7.5% trichloroacetic acid and 50% methanol, for chlorophyll removal, prior to microscopy for manual assessment of the haustorial index: GUS-stained epidermal cells with haustoria/total number of GUS-stained epidermal cells. The effect of the individual construct was normalized to the empty vector control in each experiment. A minimum of 200 GUS-stained cells were analyzed in each replicate. All experiments were reproduced at least twice with similar results. For bright-field microscopy images, a Nikon Eclipse 80i equipped with a Nikon digital light DS-SM camera was used.

Analysis of Gene Expression

Seven-day-old-barley leaves were inoculated with Bgh (virulent isolate A6). Total RNA from whole leaves and cDNA were prepared as above. Quantification of the ARFA1b transcript was performed on a Stratagene MX3000P real-time PCR detection system using Stratagene Brilliant II SYBR Green Master Mix. The quantitative PCR assay was performed on three independently isolated RNA samples, and each sample was loaded in triplicates. Expression was normalized to the expression of GAPDH. Primers used are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online.

Confocal Microscopy, BFA Treatment, and FM4-64 Staining

Gene constructs encoding fluorescent fusion proteins were bombarded 24 h prior to microscopy. GFP, YFP, RFP, and FM4-64 fluorescent signals were visualized using a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope equipped with argon/krypton and Gre-Ne lasers and filters for GFP, YFP, and RFP/FM4-64 fluorescence. For excitation of GFP and YFP, we used the 488- and 496-nm lines of the argon/krypton laser, respectively. For excitation of RFP and FM4-64, we used the 543-nm lines of the Gre-Ne laser. Detection wavelengths of emitted light were 500 to 520 nm (GFP), 520 to 540 nm (YFP), and 610 to 630 nm (RFP and FM4-64). BFA treatments were performed as previously described (Grebe et al., 2003), and FM4-64 staining was performed according to Xu and Scheres (2005). All shown experiments were repeated at least three times, with similar results.

Callose Staining

For quantification of callose deposition at Bgh penetration sites, barley leaves were chlorophyll destained in 70% followed by 96% ethanol and subsequently stained in 0.01% aniline blue and 1 M glycine, pH 9.0, for 4 h. This procedure was used for green leaves as well as for GUS-stained, trichloroacetic acid–cleared leaves that previously had been bombarded. Callose detection in the leaves with ARFA1b-eGFP–expressing cells was performed on untransformed Bgh-attacked cells. The leaves were mounted in 30% glycerol for microscopy. Callose deposits induced by Bgh appressoria were counted manually using UV fluorescence.

Accession Numbers

Accession numbers and allocated gene names for Arabidopsis and barley ARF GTPase and a yeast gene sequence, used as an outgroup, are shown in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Multiple Sequence Alignments and Transcript Levels of Barley ARF-GTPases.

Supplemental Figure 2. Haustoria Develop Normally in Cells with ARFA1b/1c-T31N and ARFA1b/1c-Q71L–Induced Susceptibility.

Supplemental Figure 3. ARFA1b/1c-eGFP Functions as the Wild-Type Enzyme and ARFA1b/1c-eGFP Organelles Stay Recruited to the Penetration Site for a Prolonged Period of Time.

Supplemental Table 1. Accession Numbers and Names of ARF GTPases.

Supplemental Table 2. Primer Overview.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Text File of the Alignment Used to Generate the Tree of ARF GTPases in Figure 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick Schweizer (Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research, Gatersleben, Germany) and Ralph Panstruga (Max Planck Institute, Cologne, Germany) for providing vectors and constructs used in these studies. We thank Paul Schulze-Lefert (Max Planck Institute, Cologne, Germany) for providing barley ror2 seeds. Financial support was provided by The Danish Council for Independent Research/Technology and Production Sciences and The Danish Council for Independent Research/Natural Sciences.

References

- An Q., Ehlers K., Kogel K.H., van Bel A.J., Hückelhoven R. (2006a). Multivesicular compartments proliferate in susceptible and resistant MLA12-barley leaves in response to infection by the biotrophic powdery mildew fungus. New Phytol. 172: 563–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Q., van Bel A.J., Hückelhoven R. (2007). Do plant cells secrete exosomes derived from multivesicular bodies? Plant Signal. Behav. 2: 4–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Q.L., Hückelhoven R., Kogel K.H., van Bel A.J.E. (2006b). Multivesicular bodies participate in a cell wall-associated defence response in barley leaves attacked by the pathogenic powdery mildew fungus. Cell. Microbiol. 8: 1009–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaad F.F., Qiu J.L., Youngs H., Ehrhardt D., Zimmerli L., Kalde M., Wanner G., Peck S.C., Edwards H., Ramonell K., Somerville C.R., Thordal-Christensen H. (2004). The PEN1 syntaxin defines a novel cellular compartment upon fungal attack and is required for the timely assembly of papillae. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 5118–5129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek P., Pislewska-Bednarek M., Svatos A., Schneider B., Doubsky J., Mansurova M., Humphry M., Consonni C., Panstruga R., Sanchez-Vallet A., Molina A., Schulze-Lefert P. (2009). A glucosinolate metabolism pathway in living plant cells mediates broad-spectrum antifungal defense. Science 323: 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R.A., Miklis M., Schmelzer E., Schulze-Lefert P., Panstruga R. (2005). Recruitment and interaction dynamics of plant penetration resistance components in a plasma membrane microdomain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102: 3135–3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-Y., Kim J.-Y. (2009). Callose synthesis in higher plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 4: 489–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coemans B., Takahashi Y., Berberich T., Ito A., Kanzaki H., Matsumura H., Saitoh H., Tsuda S., Kamoun S., Sági L., Swennen R., Terauchi R. (2008). High-throughput in planta expression screening identifies an ADP-ribosylation factor (ARF1) involved in non-host resistance and R gene-mediated resistance. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9: 25–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins N.C., Thordal-Christensen H., Lipka V., Bau S., Kombrink E., Qiu J.L., Hückelhoven R., Stein M., Freialdenhoven A., Somerville S.C., Schulze-Lefert P. (2003). SNARE-protein-mediated disease resistance at the plant cell wall. Nature 425: 973–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dascher C., Balch W.E. (1994). Dominant inhibitory mutants of ARF1 block endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi transport and trigger disassembly of the Golgi apparatus. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 1437–1448 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies B.A., Lee J.R.E., Oestreich A.J., Katzmann D.J. (2009). Membrane protein targeting to the MVB/lysosome. Chem. Rev. 109: 1575–1586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong W.B., Nowara D., Schweizer P. (2006). Protein polyubiquitination plays a role in basal host resistance of barley. Plant Cell 18: 3321–3331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douchkov D., Nowara D., Zierold U., Schweizer P. (2005). A high-throughput gene-silencing system for the functional assessment of defense-related genes in barley epidermal cells. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18: 755–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East M.P., Kahn R.A. (2010). Models for the functions of ArfGAPs. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol., in press [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichmann R., Hückelhoven R. (2008). Accommodation of powdery mildew fungi in intact plant cells. J. Plant Physiol. 165: 5–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evert R.F., Eichhorn S.E. (1976). Sieve-element ultrastructure in Platycerium bifurcatum and some other polypodiaceous ferns: The nacreous wall thickening and maturation of the protoplast. Am. J. Bot. 63: 30–48 [Google Scholar]

- Freialdenhoven A., Peterhansel C., Kurth J., Kreuzaler F., Schulze-Lefert P. (1996). Identification of genes required for the function of non-race-specific mlo resistance to powdery mildew in barley. Plant Cell 8: 5–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grebe M., Xu J., Möbius W., Ueda T., Nakano A., Geuze H.J., Rook M.B., Scheres B. (2003). Arabidopsis sterol endocytosis involves actin-mediated trafficking via ARA6-positive early endosomes. Curr. Biol. 13: 1378–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas T.J., Sliwinski M.K., Martínez D.E., Preuss M., Ebine K., Ueda T., Nielsen E., Odorizzi G., Otegui M.S. (2007). The Arabidopsis AAA ATPase SKD1 is involved in multivesicular endosome function and interacts with its positive regulator LYST-INTERACTING PROTEIN5. Plant Cell 19: 1295–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang I., Robinson D.G. (2009). Transport vesicle formation in plant cells. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 12: 660–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs A.K., Lipka V., Burton R.A., Panstruga R., Strizhov N., Schulze-Lefert P., Fincher G.B. (2003). An Arabidopsis callose synthase, GSL5, is required for wound and papillary callose formation. Plant Cell 15: 2503–2513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillais Y., Fobis-Loisy I., Miège C., Gaude T. (2008). Evidence for a sorting endosome in Arabidopsis root cells. Plant J. 53: 237–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J.D., Dangl J.L. (2006). The plant immune system. Nature 444: 323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Inzé D., Depicker A. (2002). GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7: 193–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S., André A., Edwards H., Ehrhardt D., Somerville S. (2005). Arabidopsis thaliana subcellular responses to compatible Erysiphe cichoracearum infections. Plant J. 44: 516–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C., et al. (2008). Co-option of a default secretory pathway for plant immune responses. Nature 451: 835–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G.J., Sohn E.J., Lee M.H., Hwang I. (2004). The Arabidopsis rab5 homologs rha1 and ara7 localize to the prevacuolar compartment. Plant Cell Physiol. 45: 1211–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann H., Schulz D. (1969). Elektronenmikroskopische Untersuchungen von Differenzierungsvorgängen bei Moosen II. Die Zellplatten- und Zellwandbildung. Planta 85: 313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipka V., et al. (2005). Pre- and postinvasion defenses both contribute to nonhost resistance in Arabidopsis. Science 310: 1180–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.S., Greenshields D.L., Sammynaiken R., Hirji R.N., Selvaraj G., Wei Y.D. (2007). Targeted alterations in iron homeostasis underlie plant defense responses. J. Cell Sci. 120: 596–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio J.P., Parkinson M.D.J., Gray S.R., Bright N.A. (2009). The delivery of endocytosed cargo to lysosomes. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37: 1019–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheson L.A., Suri S.S., Hanton S.L., Chatre L., Brandizzi F. (2008). Correct targeting of plant ARF GTPases relies on distinct protein domains. Traffic 9: 103–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D., Pajonk S., Micali C., O’Connell R., Schulze-Lefert P. (2009). Extracellular transport and integration of plant secretory proteins into pathogen-induced cell wall compartments. Plant J. 57: 986–999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura M.T., Stein M., Hou B.H., Vogel J.P., Edwards H., Somerville S.C. (2003). Loss of a callose synthase results in salicylic acid-dependent disease resistance. Science 301: 969–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K., Debroy S., Lee Y.H., Pumplin N., Jones J., He S.Y. (2006). A bacterial virulence protein suppresses host innate immunity to cause plant disease. Science 313: 220–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepperkok R., Whitney J.A., Gomez M., Kreis T.E. (2000). COPI vesicles accumulating in the presence of a GTP restricted arf1 mutant are depleted of anterograde and retrograde cargo. J. Cell Sci. 113: 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regente M., Corti-Monzón G., Maldonado A.M., Pinedo M., Jorrín J., de la Canal L. (2009). Vesicular fractions of sunflower apoplastic fluids are associated with potential exosome marker proteins. FEBS Lett. 583: 3363–3366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels A.L., Giddings T.H., Jr, Staehelin L.A. (1995). Cytokinesis in tobacco BY-2 and root tip cells: A new model of cell plate formation in higher plants. J. Cell Biol. 130: 1345–1357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart M.G., Aist J.R., Israel H.W. (1986). Structure and function of wall appositions.1. General histochemistry of papillae in barley coleoptiles attacked by Erysiphe graminis f.sp. hordei. Can. J. Bot. 64: 793–801 [Google Scholar]

- Stein M., Dittgen J., Sánchez-Rodríguez C., Hou B.H., Molina A., Schulze-Lefert P., Lipka V., Somerville S. (2006). Arabidopsis PEN3/PDR8, an ATP binding cassette transporter, contributes to nonhost resistance to inappropriate pathogens that enter by direct penetration. Plant Cell 18: 731–746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi M., Ueda T., Yahara N., Nakano A. (2002). Arf1 GTPase plays roles in the protein traffic between the endoplasmic reticulum and the Golgi apparatus in tobacco and Arabidopsis cultured cells. Plant J. 31: 499–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007). MEGA4: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24: 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C., Ostrowski M., Segura E. (2009). Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9: 581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J. (1994). CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thordal-Christensen H., Zhang Z.G., Wei Y.D., Collinge D.B. (1997). Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley-powdery mildew interaction. Plant J. 11: 1187–1194 [Google Scholar]

- Vernoud V., Horton A.C., Yang Z., Nielsen E. (2003). Analysis of the small GTPase gene superfamily of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 131: 1191–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Röpenack E., Parr A., Schulze-Lefert P. (1998). Structural analyses and dynamics of soluble and cell wall-bound phenolics in a broad spectrum resistance to the powdery mildew fungus in barley. J. Biol. Chem. 273: 9013–9022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei T., Hibino H., Omura T. (2009). Release of Rice dwarf virus from insect vector cells involves secretory exosomes derived from multivesicular bodies. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2: 324–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.X., Mendgen K. (1994). Endocytosis of 1,3-beta-glucans by broad bean cells at the penetration site of the cowpea rust fungus (haploid stage). Planta 195: 282–290 [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Scheres B. (2005). Dissection of Arabidopsis ADP-RIBOSYLATION FACTOR 1 function in epidermal cell polarity. Plant Cell 17: 525–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeyen R.J., Carver T.L.W., Lyngkjær M.F. (2002). Epidermal cell papillae. The Powdery Mildews. A Comprehensive Treatise, Bélanger R.R., Bushnell W.R., Dik A.J., Carver T.L.W., (St. Paul, MN: The American Phytopathological Society; ), pp. 107–125 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.