Abstract

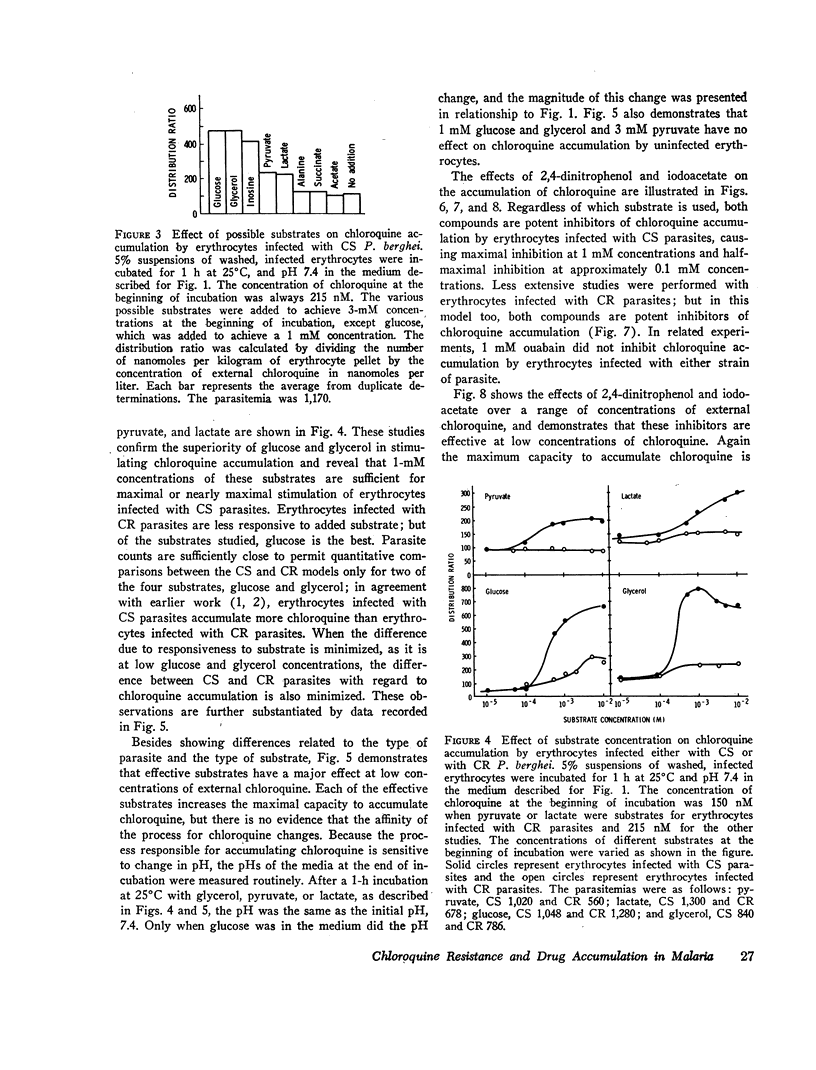

Washed erythrocytes infected with chloroquine-susceptible (CS) or with chloroquine-resistant (CR) P. berghei were used in model systems in vitro to study the accumulation of chloroquine with high affinity. The CS model could achieve distribution ratios (chloroquine in cells: chloroquine in medium) of 100 in the absence of substrate. 200—300 in the presence of 10 mM pyruvate or lactate, and over 600 in the presence of 1 mM glucose or glycerol. In comparable studies of the CR model, the distribution ratios were 100 in the absence of substrate and 300 or less in the presence of glucose or glycerol. The presence of lactate stimulated chloroquine accumulation in the CR model, whereas the presence of pyruvate did not. Lactate production from glucose and glycerol was undiminished in the CR model, and ATP concentrations were higher than in the CS model. Cold, iodoacetate, 2,4-dinitrophenol, or decreasing pH inhibited chloroquine accumulation in both models. These findings demonstrate substrate involvement in the accumulation of chloroquine with high affinity.

In studies of the CS model, certain compounds competitively inhibited chloroquine accumulation, while others did not. This finding is attributable to a specific receptor that imposes structural constraints on the process of accumulation. For chloroquine analogues, the position and length of the side chain, the terminal nitrogen atom of the side chain, and the nitrogen atom in the quinoline ring are important determinants of binding to this receptor.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aikawa M. High-resolution autoradiography of malarial parasites treated with 3 H-chloroquine. Am J Pathol. 1972 May;67(2):277–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa M. Parasitological review. Plasmodium: the fine structure of malarial parasites. Exp Parasitol. 1971 Oct;30(2):284–320. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(71)90094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWMAN I. B., GRANT P. T., KERMACK W. O. The metabolism of Plasmodium berghei, the malaria parasite of rodents. I. The preparation of the erythrocytic form of P. berghei separated from the host cell. Exp Parasitol. 1960 Apr;9:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(60)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRYANT C., VOLLER A., SMITH M. J. THE INCORPORATION OF RADIOACTIVITY FROM (14C)GLUCOSE INTO THE SOLUBLE METABOLIC INTERMEDIATES OF MALARIA PARASITES. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1964 Jul;13:515–519. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1964.13.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman I. B., Grant P. T., Kermack W. O., Ogston D. The metabolism of Plasmodium berghei, the malaria parasite of rodents. 2. An effect of mepacrine on the metabolism of glucose by the parasite separated from its host cell. Biochem J. 1961 Mar;78(3):472–478. doi: 10.1042/bj0780472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FULTON J. D., SPOONER D. F. The in vitro respiratory metabolism of erythrocytic forms of Plasmodium berghei. Exp Parasitol. 1956 Jan;5(1):59–78. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(56)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch C. D. Chloroquine resistance in malaria: a deficiency of chloroquine binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969 Dec;64(4):1181–1187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.4.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch C. D. Chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum: difference in the handling of 14C-amodiaquin and 14C-chloroquine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973 May;3(5):545–548. doi: 10.1128/aac.3.5.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch C. D. Plasmodium falciparum in owl monkeys: drug resistance and chloroquine binding capacity. Science. 1970 Jul 17;169(3942):289–290. doi: 10.1126/science.169.3942.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good N. E., Winget G. D., Winter W., Connolly T. N., Izawa S., Singh R. M. Hydrogen ion buffers for biological research. Biochemistry. 1966 Feb;5(2):467–477. doi: 10.1021/bi00866a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells R. E., Maxwell L. Citric acid cycle activity and chloroquine resistance in rodent malaria parasites: the role of the reticulocyte. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1973 Sep;67(3):285–300. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1973.11686889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladda R., Sprinz H. Chloroquine sensitivity and pigment formation in rodent malaria. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1969 Feb;130(2):524–527. doi: 10.3181/00379727-130-33596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macomber P. B., O'Brien R. L., Hahn F. E. Chloroquine: physiological basis of drug resistance in Plasmodium berghei. Science. 1966 Jun 3;152(3727):1374–1375. doi: 10.1126/science.152.3727.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polet H., Barr C. F. Chloroquine and dihydroquinine. In vitro studies by their antimalarial effect upon Plasmodium knowlesi. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1968 Dec;164(2):380–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polet H., Barr C. F. Uptake of chloroquine-3-H3 by plasmodium knowlesi in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1969 Jul;168(1):187–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]