Abstract

Mucocele of the appendix is a nonspecific term that is used to describe an appendix abnormally distended with mucus. This may be the result of either neoplastic or non-neopleastic causes and may present like most appendiceal pathology with either mild abdominal pain or life-threatening peritonitis. Urologie manifestations of mucocele of the appendix have rarely been reported. Laparoscopy can be used as a diagnostic tool in equivocal cases. Conversion to laparotomy may be indicated if there is a special concern for the ability to remove the appendix intact or if more extensive resection is warranted, as in malignancy. We here report our experience with a woman presenting with hematuria whose ultimate diagnosis was mucocele of the appendix, and we review the appropriate literature. This case highlights the mucocele as a consideration in the differential diagnosis of appendiceal pathology and serves to remind the surgeon of the importance for careful intact removal of the diseased appendix.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Hematuria, Mucocele, Appendix

INTRODUCTION

Mucocele of the appendix is a nonspecific term that is used to describe an appendix abnormally distended with mucus. This may be the result of either neoplastic or non-neoplastic causes and may present like most appendiceal pathology with either mild abdominal pain or life-threatening peritonitis. Urologie manifestations of mucocele of the appendix have rarely been reported. We report our experience with a woman with mucocele of the appendix and review the relevant literature.

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old female presented to our service with the complaint of lower abdominal and back pain increasing in severity over the last month. She stated she experienced a single episode of gross hematuria one month ago and that although she had not noted other occur-rences of hematuria, the abdominal pain consistently was worse with urination. The patient described the pain as sharp and constant. She denied nausea, vomiting or a change in bowel habits, but had been having occasional fever. She was seen twice in the Emergency department without diagnosis or resolution.

The patient's past medical history included a tubal ligation, a cholecystectomy, and a pituitary adenoma diagnosed but not treated. She denied any history of kidney stones. The patient is married with two children, smokes one-half pack per day and drinks alcohol occasionally. Her family history is remarkable only for thyroid disease.

Physical exam was significant only for a diffusely tender abdomen upon palpation without peritoneal signs. The pain was more pronounced on the right anterior abdomen and right flank. The remainder of the physical exam was unremarkable. Labs were noncontributory other than a white blood cell (WBC) count of 12,000/ml.

Cystoscopy, upper GI endoscopy and colonoscopy were negative. KUB (kidney, ureter, bladder) plain film was significant for a pea-sized opacity seemingly outside the right lower border of the right kidney. Intravenous pyelography revealed a duplex ureter on the right and no filling defects in the urinary system and confirmed an opacity apparently outside the free edge of the right kidney (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Intravenous pyelogram showing duplex ureter and multiple opacities outside the free edge of the right kidney.

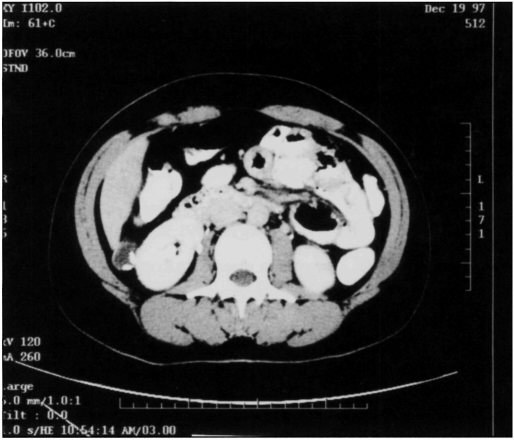

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a 7 cm × 1.5 cm tube-like structure extending from the cecum to the liver and was otherwise within normal limits (Figure 2, 3).

Figure 2.

CT of abdomen showing soft tissue density in the area of the cecum with associated calcification.

Figure 3.

CT of abdomen at the level of the lower liver showing upper extent of cecal-based mass with calcification.

At laparoscopy, the patient was found to have a grossly dilated appendix that extended from the retroperitoneal cecum to the liver posteriorly. It was detached from the liver and successfully removed intact laparoscopically (Figure 4). The patient's postoperative course was uneventful. Pathologic examination revealed a benign mucinous cystadenoma with mucocele formation (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Laparoscopic view of grossly dilated appendix being dissected off the cecum; the distal portion was first detached from the liver.

Figure 5.

Microscopic appearance characteristic of mucinous cystadenoma; there is no evidence of deep tissue invasion.

DISCUSSION

Mucocele of the appendix has been described to occur more often in females and at an average age over 50.l It was originally characterized in 1973 with the term retention cyst to describe a sterile outflow obstruction in the appendix that was dilated and swollen with glairy mucus. The term mucocele has more recently been substituted. Patients almost always present with symptoms that are characteristic of any number of abdominal or pelvic conditions. The porcelain appendix and the so-called volcano sign are two nonspecific diagnostic clues, but CT remains the most suggestive tool. Mucoceles are occasionally diagnosed incidentally in the course of other surgery. On ultrasound, they have been known to mimic ovarian cyst torsion.

Mucoceles can be classified histologically into three types: Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix may be benign, taking the form of hyperplasia or cystadenoma, or may more rarely occur as cystadenocarcinoma, which is malignant. Both benign and malignant mucoceles may spontaneously rupture, secondary presumably to hypersecretion of mucus. These patients may present with a peritoneal cavity filled with mucus, informally described as “jelly belly.”

Mucocele characterized only by mucosal hyperplasia is an entity that macroscopically resembles a hyperplastic colorectal polyp. Cystadenomas are also benign and may be treated similarly. Simple appendectomy with free margins is curative for these nonmalignant mucoceles as long as they have not ruptured.

Treatment for malignant mucoceles is distinct in that the histologie diagnosis following appendectomy warrants a return to the operating room for a right hemicolectomy. Because the neoplastic diagnosis is only determined by pathology, removal of the appendix requires caution as inadvertent rupture may lead to seeding of the malignancy causing pseudomyxoma peritonei. Although rupture of a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma does not result in systemic metastasis, excessive mucin in the peritoneum and pseudomyxoma peritonei may cause death due to infection or intestinal obstruction.

Laparoscopy can be used as a diagnostic tool in those cases which are equivocal. Conversion to laparotomy may be indicated if there is special concern for the ability to remove the appendix intact or if more extensive resection is warranted, as in malignancy.

Various etiologies have been reported. Mucoceles secondary to obstruction have been reported to occur in endometriosis, cystic fibrosis, and in cases of carcinoid. Additionally, mucocele has occasionally been reported to cause small bowel obstruction secondary to volvulus and to intussusception. There has been one report of a mucocele secondary to diverticulitis.2

Mucocele of the appendix rarely presents with urologie manifestations. Local or mass effects of mucoceles have been reported to cause hydronephrosis, and classic symptoms of urinary tract infection (UTI), but have very seldom been reported to cause hematuria alone.3,4 In one case report, mucocele was responsible for infertility, which resolved upon surgical removal of the diseased appendix.

A variety of abnormalities of the appendix underscores the need for routine pathologic examination of the appendix. Histopathology often changes both the diagnosis and the treatment, as in occult parasitic infestation and malignancies.

CONCLUSION

Although uncommonly reported in the literature, urologie symptoms may be a manifestation of appendiceal pathology. In this case, back pain with hematuria was the primary presentation of a benign cystadenomatous mucocele of the appendix. Laparoscopy allowed for definitive diagnosis and therapy. We recommend laparoscopy as the initial intervention and emphasize the need for the careful intact removal of a suspected mucocele of the appendix.

Contributor Information

Uretz J. Oliphant, FACS, FICS. Head, Department of Surgery University of Illinois, College of Medicine at Urbana-Champaign, Carle Clinic Association..

Andrew Rosenthal, MBA. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Carle Clinic Association..

References:

- 1. Landen S, Bertrand C, Maddern GJ, et al. Appendiceal mucoceles and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:401–404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sivam NS, Ananthakrishnan N, Kate V. A case of appendicular diverticulitis leading to mucocele of the appendix. Trop Gastroenterology. 1997;18:36–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baskin LS, Stoller ML. Unusual appendiceal pathology presenting as urologie disease. Urology. 1991;38:432–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vale J, Kirby RS. Hematuria due to mucocele of the appendix. Br J Urology. 1989;63:218–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]