Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Laparoscopic surgical techniques in pregnancy have been accepted and pose minimal risks to the patient and fetus. We present the first reported case of a pregnant woman with immune thrombocytopenia purpura who underwent laparoscopic splenectomy during the second trimester.

Methods and Results:

The anesthesia, hematology, and obstetrics services closely followed the patient's preoperative and intraoperative courses. After receiving immunization, stress dose steroids, and prophylactic antibiotics, she underwent a successful laparoscopic splenectomy. After a short hospital stay, the patient was discharged home.

Conclusion:

Immune thrombocytopenia purpura can be an indication for splenectomy. As demonstrated in appendectomy, cholecystectomy, and our case presentation, laparoscopic splenectomy can be safely performed during pregnancy.

Keywords: Thrombocytopenia, Laparoscopy, Splenectomy, Pregnancy

INTRODUCTION

Since the advent of laparoscopic surgery in the early 1980s, multiple applications for it have been found in almost all surgical specialties. Laparoscopic procedures in pregnancy are becoming accepted as clinicians gain more experience. Minimally invasive management of appendicitis and acute cholecystitis has been accepted as safe in the pregnant patient and is supported by several case reports and studies. Other procedures will likely be added to this armamentarium.

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is an autoimmune disorder in which IgG autoantibodies bind to the platelet membrane.1 This causes premature clearance of platelets by macrophages in the spleen and other organs of the reticulo-endothelial system. The spleen is believed also to be a major source of autoantibody production in this disorder. ITP may be acute or chronic: the chronic form is more common in adult patients. The female to male ratio is 2:1. Women with this anomaly range in age from 20 to 40 years. Thus, ITP often complicates pregnancy, although pregnancy per se is not believed to induce ITP or alter the disease course. These IgG antibodies are actively transported across the placenta making diagnosis during pregnancy critical. Prednisone constitutes a very effective first-line treatment in most patients with ITP, but only about 25% of patients maintain acceptable platelet counts when steroids are tapered off or withdrawn. For the majority of those who fail corticosteroids, splenectomy is very effective in inducing a remission with 70 to 80% of patients with ITP responding either to corticosteroids or splenectomy.1

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The patient is a 21-year-old Hispanic female, gravida 2, para 1, in her 23rd week of pregnancy. During her first prenatal visit at 11 weeks gestation, a routine laboratory examination revealed a platelet count of 12,000. She denied previous bleeding complications with her first pregnancy, but she had not sought prenatal care for laboratory assessment at that time. During this, her second pregnancy, the patient sought medical care and reported gum bleeding when she brushed her teeth and easy bruising. She was evaluated in the Hematology Clinic within the week and found to have a platelet count of 2,000/mL. Due to this extremely low platelet count, the patient was admitted to the hospital. She was considered to have ITP on the basis of her history, the absence of abnormal physical findings, and an isolated thrombocytopenia with otherwise normal hematological parameters and blood smear. The results of the analysis of other relevant hematologic parameters were: negative antinuclear antibody, negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibody, and normal prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time. Liver synthetic function and transaminases were normal, as was renal function, based on blood chemistry. A bone marrow biopsy was not performed, in keeping with the American Society of Hematology guidelines.2

Prednisone therapy at 2 mg/kg was initiated, and the platelet count rose quickly reaching a maximum of 60,000/mL. As the steroid therapy was tapered from 60 mg twice a day (BID) at discharge to 20 mg BID over a 3-week period, the platelet counts dropped, and the patient developed bruising and had a platelet count of 30,000/mL. We increased the prednisone to 40 mg BID. The patient was very bothered by the Cushingoid effects of the corticosteroids. On one occasion, she stopped her steroid therapy abruptly. She came to the clinic and was found to have a platelet count of 30,000/mL. In addition to our concern about her lack of compliance, we were also concerned with the steroid's late effects, including pregnancy-induced hypertension, especially in light of the relatively high doses needed to keep her platelet count at a safe and asymptomatic level. We considered giving her intravenous gamma globulin therapy, but it requires a compliant patient for laboratory follow-up and repeat dosing.

We considered this a treatment failure and therefore discussed possible surgical approaches. Ultrasound at 20 weeks demonstrated a healthy fetus. After consultation between the perinatologists and hematologists involved in this case, we offered splenectomy as an alternative therapy. We discussed the risks and benefits of splenectomy in the second trimester with the patient who elected to undergo the laparoscopic splenectomy.

Approximately 2 weeks before the procedure, the patient was given pneumococcal, meningococcal, and hemophilus influenzae vaccines in preparation for the splenectomy. Her prednisone dose was also increased to 40 mg BID to obtain a higher platelet count for the surgical procedure. She was typed and crossed for 2 units of packed red cells. Bolus intravenous steroids of 100 mg every 6 hours were given to provide stress-dose therapy. The platelet count was 158,000/mL at the time of splenectomy. Prophylactic antibiotics were also administered. Sequential or intermittent compression devices were also used to prevent deep venous thrombosis.

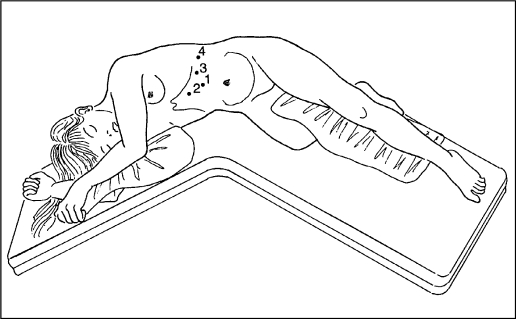

In the operating room, the patient was placed in the left lateral position during induction keeping the uterus off the vena cava. A fetal heart rate of 144 beats/minute was measured prior to surgery. Aggressive hydration was given to prevent hemodynamic changes associated with pneumoperitoneum. The patient was then placed in the right lateral position. The operating table was broken to open the distance between the costal margin and the iliac crest. The Hasson cannula was placed under direct visualization (Figure 1).3 Insufflation was kept below 14 mm Hg and the end-tidal CO2 was monitored continuously during the procedure. The remaining ports were placed as indicated (Figure 1),3 using 12-mm ports so that the stapling device [Endo Vascular GIA (USSC, Norwalk, CT)] could be best positioned.

Figure 1.

ITP: Laparoscopic treatment.

Dissection began with the splenocolic ligament. Traction on the splenic flexure of the colon was maintained using a laparoscopic Babcock while shears with monopolar cautery were used to divide the attachments. The ultrasonic coagulator was used to divide the splenorenal and splenophrenic attachments. The spleen was lifted and rotated using a closed Babcock. The lesser sac was entered as the gastrosplenic ligament, and short gastric vessels were taken with the ultrasonic coagulator. Careful spreading with a blunt dissector exposed the hilar vessels, which were divided with the vascular stapler [Endo Vascular GIA (USSC, Norwalk, CT)]. Three applications of the device were used. The 6” x 8” entrapment sac was then placed through a port site. The staple line at the splenic hilum was grasped to deposit the spleen in the sac. The spleen was morsellated in the sac with a ring forcep prior to removal through a port site. The splenic vessels were inspected and the operative site irrigated before removing all ports under direct visualization. Accessory splenic tissue was not visualized. The fascia was closed under laparoscopic guidance.

RESULTS

No operative or obstetric complications occurred. Blood loss was less than 100 cc. The patient received 3 L of crystalloid and made 1300 cc of urine. Systolic blood pressure was maintained in the range of 105 to 125 mm Hg. End-tidal CO2 measurements ranged from 30 to 35 (units). The operative time was 4 hours and 20 minutes. A fetal heart rate of 150 beats/minute was noted in the recovery room. On postoperative day 1, the platelet count was 213,000/mL. Sequential compression devices were continued, as venous thrombosis is a concern with extremely elevated platelet counts that can occur after splenectomy. A maximum level of 600,000/mL was reached on postoperative day 9 that subsequently fell to the normal range. A normal platelet count was maintained through the remainder of her pregnancy. The patient was discharged home on an oral pain medication and a steroid taper. The pregnancy resulted in a term infant delivered vaginally without bleeding complications. At the time of delivery, the maternal platelet count was 357,000/mL, and the baby's platelet count was 310,000/mL. Approximately 1 year after splenectomy, a small port site hernia was repaired, primarily on an outpatient basis. The patient's platelet count at that time was 345,000/mL.

DISCUSSION

Isolated thrombocytopenia during pregnancy can have diverse causes. An asymptomatic reduction in platelet counts, between 90,000/mL and 150,000/mL, is usually considered “gestational” thrombocytopenia and of no clinical significance.4 Lower platelet counts suggest ITP. Other causes include HIV-associated thrombocytopenia, lupus, malignancy and microangiopathic hemolytic processes. Appropriate laboratory tests ruled out the former anomalies in this patient; neither clinical nor laboratory evidence of malignancy or HEELP syndrome (HEmolysis, Elevated Liver function, Low Platelets) existed.

Immunoglobulin therapy is considered safe in the pregnant patient but is extremely costly and requires a compliant patient. The initial treatment costs approximately $10,000 with maintenance treatments costing $2,500 to $5,000. At the time of presentation, immunoglobulin was in a severe shortage. Steroid therapy can worsen gestational diabetes, predispose the patient to infection, and complicate pregnancy-induced hypertension. Both regimens are considered safe for the fetus. Immunoglobulin G crosses the placenta in increasing amounts as gestation increases and may benefit the fetus at delivery.5 Cytotoxic agents such as azathioprine or cyclophosphamide are assumed to be teratogenic.2 Because the maternal IgG antibodies are transported across the placenta, the fetus can become thrombocytopenic. Maternal platelet counts and response to treatment do not reliably predict fetal platelet counts. The concern then is for fetal injury during delivery, namely intracerebral hemorrhage. In a review of the literature concerning pregnant women with ITP, the incidence of infant platelet counts less than 50,000/mL is between 6% and 70%, but severe thrombocytopenia less than 20,000/mL is 7%.6,7

A treatment strategy for gravidas with ITP is difficult to formulate. If the mother is asymptomatic and the fetal platelet count is normal, no therapy would be indicated. However, the fetal platelet count is difficult to predict. It cannot be determined without invasive sampling that carries the risks of fetal distress, bradycardia, and even death.2 Additionally, maternal steroid therapy does not prevent fetal thrombocytopenia.7 A panel of hematologists from the American Society of Hematologists in 1996 could not reach a consensus as to a treatment plan. They were less likely to recommend splenectomy due to perceived maternal and fetal risks.2 Our case presentation presents laparoscopic splenectomy, an alternative with the added benefits of less need for narcotics, earlier return to activity, and the avoidance of uterine manipulation.

Several physiological differences exist in the pregnant patient that must be considered before proceeding with any surgical procedure. In regard to hemodynamics, systemic vascular resistance in pregnancy is decreased by 2 mechanisms. Progesterone exerts direct smooth muscle relaxation in both the vascular tree and the gastrointestinal tract. The second mechanism is prostacycline production, which causes desensitization of the vascular beds to catecholamines.8 This is important with induction and abdominal insufflation. The patient must be well hydrated and positioned so that the uterus does not compromise cardiac return.

A second important consideration is the acid-base regulation during pregnancy. The patient maintains a compensated respiratory alkalosis due to increased tidal volumes and respiratory rates. The kidneys compensate by excreting bicarbonate.8 The gravid patient is therefore more susceptible to acidosis as is the fetus. Again, adequate hydration and proper positioning are important.

Carbon dioxide absorption during pneumoperitoneum is also an issue. Hunter et al9 studied the effects of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum in pregnant sheep. They found that the pH of both the ewe and the fetus decreased. However, respiratory compensation occurred in 30 minutes. After desufflation, all parameters returned to normal. The conclusion from this study is that pneumoperitoneum does not place the fetus at significant risk. Similar results were found in other animal studies.10

Laparoscopy during pregnancy has been found to be as safe as open surgery. A Swedish study11 showed that no difference occurs in fetal demise and fetal malformations between patients undergoing laparoscopy or laparotomy.

Another issue is that the pregnant patient is in a hypercoagulable state due to the increased production of clotting factors. A 20% increase occurs on average in fibrinogen levels.8 Perioperatively, these patients therefore need prophylactic measures such as sequential compression devices or low-dose heparin therapy. A benefit of laparoscopic procedures in general is the earlier return to activity avoiding prolonged bedrest and the inherent possible complications.

Benefits of Laparoscopic Surgery

Patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures often use less pain medication.12 This is important due to the deleterious effects that chronic narcotic use can have on the fetus. Chronic narcotic use has been associated with premature labor and fetal growth retardation. Fetal opiate addiction and withdrawal can lead to intrauterine fetal demise.8 Short-term use of narcotic agents has been approved. It should be remembered that NSAIDs should be avoided because these agents block prostaglandin synthesis and can lead to premature closure of the ductus arteriosus.

Laparoscopic splenectomy has been performed safely with minimal morbidity.13 It is also being safely performed in nonpregnant patients with ITP.14 Angled scopes of 30° or 45° facilitate visualization. Positioning in the right lateral position allows the spleen to fall medially facilitating dissection. The ultrasonic coagulator, used commonly in antireflux procedures, is gaining wider use. It vibrates at 55,000 cycles per second to divide and coagulate tissues. It can be used on the nonvascular splenic ligaments as well as the short gastric vessels. When dividing vessels, it is better to place a short burst proximally and distally on the vessel before dividing. This is the method used in our patient with minimal blood loss. Other options for dividing the vessels include suture ligation or Ligaclip.13 The larger hilar vessels were divided with a vascular stapling device. At this point, bleeding can occur when vessels are partially transected. After coaxing the spleen into the entrapment sac, a morcellating device or ringed forceps can be used to break it apart for removal. Laparoscopic splenectomy in nongravid patients was successful with only 11% of patients requiring conversion to an open procedure in a study of 52 procedures.13 This conversion rate decreased with the increasing experience of clinicians, as noted in other laparoscopic procedures.

In conclusion, this report suggests that laparoscopic splenectomy may be safely performed during pregnancy confirming other recent case reports.15,16 To date, the risks to the mother and fetus have been shown to be minimal during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and appendectomy in small and large collective series up to 20 weeks gestation.11,17 It may be appropriate to extrapolate these data to laparoscopic splenectomy. The benefits of laparoscopic procedures in general are well documented. When applied to pregnant patients, the earlier return to activity and reduction in narcotic use are additional benefits that must be weighed against operative time. Randomized prospective studies are needed before laparoscopic splenectomy can be routinely offered during pregnancy.

Acknowledgment:

The authors gratefully acknowledge Southwestern Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery, which is supported in part by an educational grant from US Surgical: A Division of TYCO Healthcare.

Footnotes

This scientific paper was presented in part at the 1999 SAGES Annual Scientific Session March 25, 1999 in San Antonio, Texas, USA.

Contributor Information

Cynthia Rutherford, Department of Hematology/Oncology.

Ronald Ramus, Department of OB/GYN.

Daniel B. Jones, Southwestern Center for Minimally Invasive Surgery.

References:

- 1. Rutherford CJ, Frenkel EP. Thrombocytopenia: issues in diagnosis and therapy. Med Clin North Am. 1994;78(3)555–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. George JN, Woolf SH, Raskob GE, et al. Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a practice guideline developed by explicit methods for the American Society of Hematology. Blood. 1996;88(1):3–40 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones DB, Wu JS, Soper NJ. Laparoscopic Surgery: Principles and Procedures. St. Louis: Publishing; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shehata N, Burrows RF, Kelton JG. Gestational thrombocytopenia. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42(2):327–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scott JR, Branch DW. Immunologic Disorders. In: Creasy RK, Resnik R, eds. Maternal Fetal Medicine. 3rd ed Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co;1994:473–477 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burrows RF, Kelton JG. Pregnancy in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: assessing the risks for the infant at delivery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1993;48(12):781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCrae KR, Samuels P, Schreiber AD. Pregnancy-associated thrombocytopenia: pathogenesis and management. Blood. 1992;80:2697–2714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gianopoulos J. Establishing the criteria for anesthesia and other precautions for surgery during pregnancy. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75(1):33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hunter JG, Swanstrom L, Thornburg K. Carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum induces fetal acidosis in a pregnant ewe model. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:272–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curet MJ, Vogt DA, Schob O, Qualls C, Izquierdo LA, Zucker KA. Effects of CO2 pneumoperitoneum in pregnant ewes. J Surg Res. 1996;63:339–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reedy MB, Kallen B, Kuehl TJ. Laparoscopy during pregnancy: a study of five fetal outcome parameters with the use of the Swedish Health Registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(3):673–679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Curet MJ, Allen D, Josloff RK. Laparoscopy during pregnancy. Arch Surg. 1996;131:546–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glasgow RE, Yee LF, Mulvihill SJ. Laparoscopic splenectomy: the emerging standard. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lefor AT, Melvin WS, Bailey RW, Flowers JL. Laparoscopic slenectomy in the management of immune thrombocytopenia purpura. Surgery. 1993;114:613–618 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hardwick RH, Slade RR, Smith PA, Thompson MH. Laparoscopic splenectomy in pregnancy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9(5):439–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoey BA, Chapman WHH., III Laparoscopic splenectomy at caesarean section. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9(5):419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chamogeorgakis T, Lo Menzo E, Smink RD, Jr., et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy during pregnancy: three case reports. JSLS. 1999;3:67–69 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]