Abstract

Background:

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a diagnostic procedure with several known risks. We present two rarely reported complications of ERCP and sphincterotomy: transverse mesocolon disruption with ischemic colitis and splenic rupture.

Results:

The first patient, a 54-year-old female, presented one day following ERCP and stent revision for pancreas divisum. She presented with hypotension and abdominal distention. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a ruptured spleen, which was confirmed on laparotomy. She had a complicated postoperative course and died of multiple organ failure. The second patient is a 56-year-old female who presented five days after ERCP and sphincterotomy with abdominal pain, abdominal wall ecchymosis, and decreasing hematocrit. Her evaluation included hospital admission and abdominal CT scan, which showed free fluid and a large hematoma in the transverse mesocolon. These findings were confirmed on laparotomy and a devascularized segment of bowel was resected.

Conclusion:

Only 6 cases of ERCP-related splenic injury have been reported in the literature. One additional report is available of a fatal splenic artery injury. No previous reports exist of a mesenteric hematoma resulting in bowel devascularization. Prompt evaluation and awareness of potential complications should help capture potentially life-threatening sequelae of ERCP.

Keywords: ERCP, Complications, Spleen, Colon, Mesenteric injury

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is a diagnostic procedure with several known risks. Procedure-specific risks include esophageal perforation (0.05% to 0.1%), pancreatitis (2% to 15%, clinically significant in 1% to 5% of patients), and the potential for cholangitis.1,2 The addition of endoscopic sphincterotomy has been shown to increase morbidity and mortality and to pose unique risks, such as bleeding and duodenal or ductal perforation.

We present two cases of rarely reported ERCP complications: splenic rupture and mesenteric hematoma leading to ischemic colitis.

CASE REPORT 1

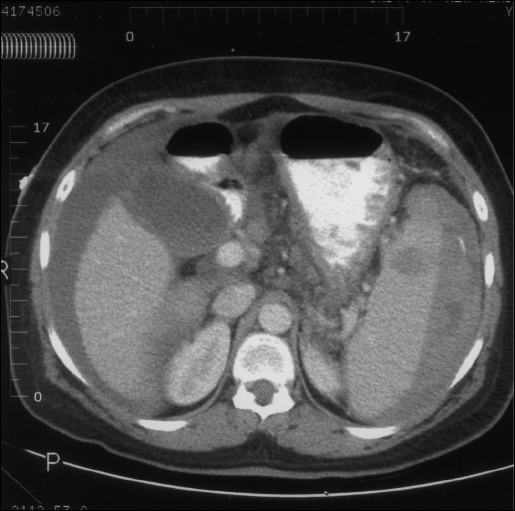

The first patient was a 54-year-old female who underwent ERCP with stent revision for pancreas divisum. Her past medical history was significant for hepatitis C, cirrhosis, and chronic pancreatitis. She presented one day following the procedure with hypotension with marked abdominal distension. After the patient responded to resuscitation, a CT scan of her abdomen was performed. The CT demonstrated a ruptured spleen (Figure 1). The patient decompensated and was taken for laparotomy. Laparotomy confirmed splenic rupture associated with massive hemoperitoneum and cirrhosis. A splenectomy was performed. Postoperatively, the patient remained ventilator-dependent and required treatment for Pseudomonas pneumonia. She also required intermittent vasopressors and hemodialysis. She died on postoperative day 40 of multiple organ failure.

Figure 1.

Abdominal CT, axial view, showing hemoperitoneum and splenic rupture

CASES REPORT 2

The second patient is a 56-year-old female who underwent ERCP and sphincterotomy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. She presented five days after the ERCP with intermittent abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, emesis, and hematochezia that had lasted for 3 to 4 days. Her past surgical history was significant for three prior abdominal operations, total abdominal hysterectomy, appendectomy, and exploratory laparotomy with ileal resection. Her past medical history was significant for chronic abdominal pain with opiate dependence, malabsorption treated with enzyme replacement, hypertension, and osteoporosis. The initial examination showed a pale but hemodynamically stable patient. Her cardiopulmonary examination was normal. Her abdomen was soft with diffuse tenderness, voluntary guarding, and distention. She was noted to have ecchymosis along her previous abdominal incisions. Stool guaiac was negative. Initial laboratory findings were significant for a hematocrit of 26% (decreased from 36%), platelets 181,000/mm3, blood urea nitrogen 38 mg/dL, creatinine 1.7 mg/dL, and amylase 209 U/L.

Resuscitation was initiated, including a transfusion of two units of blood once her hematocrit reached a nadir of 22%. Her abdominal pain continued, despite resolution of her nausea and anorexia, prompting a CT scan of the abdomen on her second hospital day, and a surgical consultation on hospital day three. The CT demonstrated free fluid within the abdomen and a large hematoma in the transverse mesocolon (Figure 2). Laparotomy confirmed a large hematoma within the transverse mesocolon due to disruption of the middle colic vessels. The transverse colon distal to the hematoma was devascularized. Blood was also noted to have dissected along associated abdominal wall adhesions and previous incisions accounting for the ecchymotic scars noted on the initial physical examination. Bowel resection and primary anastomosis were performed. Further investigation, including careful inspection of the duodenum and splenic vessels, revealed no other abnormalities. Her hospitalization was complicated by respiratory compromise requiring intubation on the first postoperative day. She had hemodynamic decompensation thereafter, requiring pharmacological support, and crystalloid resuscitation. She developed Pseudomonas pneumonia in her 12-day ventilator course. She was eventually discharged home on postoperative day 20 without further sequelae.

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT, axial view, showing a mesenteric hematoma in the transverse mesocolon and compromised bowel.

DISCUSSION

Factors affecting morbidity and mortality during ERCP include operator experience and patient comorbidity. Risk of bleeding following ERCP is increased in patients with coagulopathy and with the use of therapeutic sphincterotomy. Duodenal hematomas have been reported, as well as rupture of a gastroduodenal pseudoaneurysm following ERCP. Several case reports of splenic injury, including splenic rupture have been reported in the literature.

The first report of splenic injury following ERCP is by Trondsen et al.3 They reported a woman who underwent ERCP and sphincterotomy for acute gallstone pancreatitis. Five hours after the procedure she presented with hemoperitoneum due to a “decapsulated” spleen requiring splenectomy.

Ong et al4 later reported one case of splenic injury after ERCP. Their patient had an elective laparotomy two days following ERCP where a splenic laceration necessitating splenectomy was noted. They attributed endoscopic-related splenic injuries to traction on adhesions and looping of the endoscope.

Lewis et al5 described two cases of splenic injury following ERCP. In one patient, a hypotensive episode nine hours postprocedure led to laparotomy and splenectomy for avulsed short gastric vessels. The other patient required laparotomy for a bleeding duodenal ulcer. Hemoperitoneum was discovered from a concurrent splenic capsule avulsion so the spleen was removed. These authors likewise felt the injury was secondary to traction, despite both endoscopic procedures being described as uneventful.

Wu and Katon6 described a woman undergoing ERCP who became hypotensive with peritoneal signs three days after her procedure. Laparotomy revealed splenic capsule avulsion requiring splenectomy along with a hepatic laceration requiring repair. The authors noted intraabdominal adhesions on exploration, including adherence of the splenic capsule to the anterior abdominal wall.

Furman and Morgenstern7 also reported a subcapsular splenic hematoma reported following ERCP and papillotomy. Reiertsen et al8 reported a splenic artery injury during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and biopsy resulting in a fatal hemorrhage.

We have not found other reports of ERCP resulting in a mesenteric hematoma with associated bowel ischemia as seen in our second patient.

The majority of authors attribute splenic injury during endoscopy to looping of the endoscope and traction on the greater curvature of the stomach, short gastric vessels, and splenic capsule. Some theorize that the insufflation alone poses a risk. We also believe intraabdominal adhesions pose an increased risk for traction-related injuries. Our first case adds to the reports of splenic injury following endoscopy. Our second case appears to be the first recorded with an endoscopic mesenteric injury resulting in bowel ischemia.

The incidence of adverse outcomes should decrease as we increase our awareness of potential complications. Close clinical monitoring and prompt evaluation for postprocedure complaints should capture potentially life-threatening complications.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial or proprietary interest in the subject matter and materials discussed in this article.

References:

- 1. Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, et al. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 48:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:909–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Trondsen E, Rosseland AR, Moer A, Solheim K. Rupture of the spleen following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Acta Chir Scand. 1989; 155:75–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ong E, Bohmler U, Wurbs D. Splenic injury as a complication of endoscopy: two case reports and a literature review. Endoscopy. 1991; 23:302–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewis FW, Moloo N, Stiegmann GV, Goff JS. Splenic injury complicating therapeutic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991; 37(6):632–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu WC, Katon RM. Injury to the liver and spleen after diagnostic ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993; 39(6)824–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furman G, Morgenstern L. Splenic injury and abscess complicating endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc 1993; 7:343–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reiertsen O, Skjoto J, Jacobsen CD, Rosseland AR. Complications of fiberoptic gastrointestinal endoscopy: five years' experience in a central hospital. Endoscopy. 1987; 19:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]