Abstract

The patient is a 2-year-old Caucasian boy with acute acalculous cholecystitis (AC) but none of the predisposing factors that are typically found in patients with this disease. The presentation and clinical course of the disease was typical of AC. Nonsurgical intervention resulted in resolution of the child's initial symptoms. After recurrent bouts of biliary colic over the ensuing ten weeks, further evaluations were completed. Persistent inflammation of the gallbladder was seen on computerized tomo-graphic scans and a nonfunction of the gallbladder was demonstrated through radio-nucleotide scanning. After discussing the findings with the parents, we performed a routine laparoscopic cholecystectomy on the child. The typical presentation, diagnosis, and pathogenesis of AC are discussed.

Keywords: Acalculous cholecystitis, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Pediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Diseases of the gallbladder are uncommon in the pediatric population. When cholecystitis occurs in children, acalculous cholecystitis (AC) accounts for 30 to 50% of the cases.1 Common risk factors for AC include recent surgery,2 trauma,3 medical illness,4 and infection.5 Ternberg et al described seven AC patients all of whom had associated critical illness.4 Similarly, Tsakayannis noted that all 13 patients with acute AC in his series had recently undergone surgical procedures or had concomitant medical illnesses.2 We present a unique case of a 2-year-old male that developed acute AC without any of the reported risk factors.

CASE REPORT

A 27-month-old Caucasian boy presented to the emergency department with a two-day history of intermittent abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and anorexia. He had no history of previous similar episodes of pain or gastrointestinal distress. The child had not eaten well for the past two days and appeared mildly dehydrated.

The child had no prior medical or surgical history. Other than a report of gallbladder disease in the paternal grandmother, nothing pertinent was found in the child's medical history.

The boy's oral temperature was 101.3°F, and he appeared to be alert, active, and well nourished. His abdomen was soft, nondistended, and when examined while calm or asleep, he clearly demonstrated right upper quadrant tenderness.

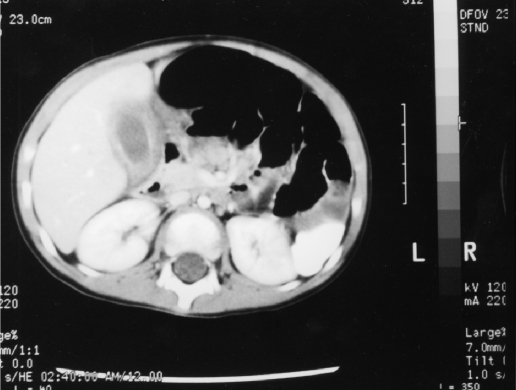

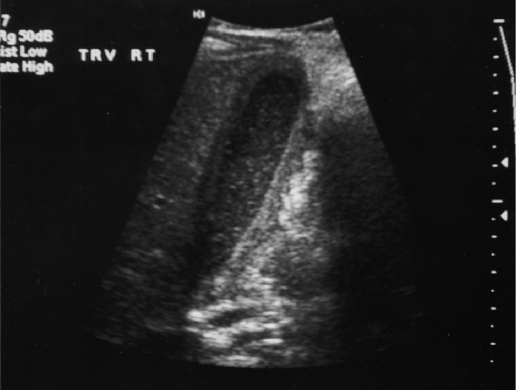

The initial abnormal laboratory studies included a white blood cell count of 22,900 with 80% neutrophils and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 31 (normal 0-10). His blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 8.0 mg/dL, and his creatinine measured 0.3 mg/dL. The child's CO2 was below the normal value at 21 meq/L, and no abnormalities were present in his liver enzymes, electrolytes, amylase, or lipase. After an initial evaluation and fluid resuscitation, the child underwent an intravenous and oral contrast enhanced computed topographic scan (CT). The CT demonstrated a large amount of fluid around the gallbladder as well as gallbladder wall thickening and inflammation (Figure 1). Neither stones nor ductal dilation were seen. A subsequent ultrasound supported these findings of inflammation and fluid around the gallbladder (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The CT demonstrates the pericholecystic fluid as well as the edema of the gallbladder wall.

Figure 2.

The ultrasound demonstrates the absence of the stones as well as the wall edema and pericholecystic fluid collection.

The child was administered a second-generation cephalosporin and received intravenous hydration. He rapidly improved, becoming afebrile and pain-free within 24 hours. Multiple cultures from serum and stool were obtained prior to and after the antibiotic therapy was initiated, but no pathogenic organisms were isolated. Screenings of the stools for rotavirus and adenoviruses were also negative. Two weeks after discharge, the patient had a hepatic imino-diacetic acid (HIDA) scan done that showed no uptake in the gallbladder. A repeat HIDA scan two months later again indicated a nonfunctioning gallbladder. His mother reported that he experienced several episodes of severe though brief abdominal pain during this two-month period. The child's gallbladder was removed through a laparoscopic approach. At surgery, the gallbladder wall appeared thickened and notable adhesions to surrounding tissues were visible. The gallbladder was examined microscopically and noted only to have flat cuboidal epithelium and a wall thickness of 0.2 cm. No calculi were found in the specimen. The child had an uneventful recovery and was discharged one day after his cholecystectomy. Two years after the surgery, the child remains in excellent health.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis of AC is multifactorial. Several factors recur that are of primary importance in predisposing a patient to developing the disease. These include any event that may contribute to a hypotensive state resulting in ischemia of the gallbladder wall. Conditions that result in a prolonged period of biliary stasis are associated with an increased incidence of AC as well. Examples of this include prolonged parenteral feedings, positive endexpiratory pressure (PEEP), or cystic duct obstruction. Biliary stasis results in a concentration of the bile, which disrupts normal biliary function by altering the transport of water across the gallbladder mucosa. This may lead to increased intraluminal pressures resulting in edema, necrosis, and an inflammatory immune response within the gallbladder wall.6 Systemic infection and sepsis predisposes an individual to secondary infection of the gall-bladder. This results in the activation of host immune mediators within the wall of the gallbladder. The resulting inflammation may make a significant contribution to the development of AC in patients with sepsis.7

All patients presenting with AC reported on in the literature have right upper quadrant pain and fever. Other associated symptoms as shown in Table 1 include fever, right-upper-quadrant mass, vomiting, leukocytosis, and abnormal liver function. Findings occur on both ultrasound and CT that are consistent with the diagnosis of AC. The ultrasound criteria used in the literature differ to some extent, but the common themes include a gall-bladder wall thickness of 3.0 mm or more, sludge in the gallbladder with an absence of stones and a pericholecystic fluid collection.8 The findings on CT that are associated with AC include a thickened gallbladder wall, pericholecystic fluid, and edematous pericholecystic fat.9 Numerous conditions are associated with developing AC. Trauma, burns, and surgery are common predisposing factors for this disease.2–4,10 Medical illnesses, such as cystic fibrosis, leukemia, cirrhosis, and Wilson's disease, are also associated with the development of AC.2,11 Sepsis from any pathogen can lead to the development of AC. Cultures from gallbladders with AC have identified several different pathogens, such as E. coli and salmonella. The incidence of cholecystitis in patients with enteric fever from Salmonella typhi is 2.8% with 60% of the cases being acalculous.5 Other infectious causes of AC include scarlet fever, gastroenteritis, and leptospirosis.4

Table 1.

Signs and Symptoms in Acalculous Cholecystitis.

| Signs and Symptoms | Occurrence (%) |

|---|---|

| Abdominal Pain | 100 |

| Fever | 95 |

| Hepatomegaly/Mass | 80 |

| Leukocytosis* | 76 |

| Vomiting | 75 |

| Increased Liver Function Test | 62 |

| A summary of findings from the reference articles for this paper. |

Only one study reported this.

CONCLUSION

A variety of predisposing or associated conditions for AC have been discussed. None of these predisposing factors were present in our patient. Typical viral and bacterial pathogens were not detected though gallbladder cultures were not obtained. The patient was not markedly dehydrated prior to admission despite not having eaten well in two days prior to admission. The role of gastroenteritis in the development of AC is unclear and needs to be further investigated. No other reports of such patients have been found in the literature to date. We conclude that this child represents a unique case of AC, raising the question of the existence of other unrecognized similar cases.

References:

- 1. Glenn F. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Ann Surg. 1979; 189(4): 458–465 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tsakayannis DE, Kozakewich HP, Lillehei CW. Acalculous cholecystitis in children. J Ped Surg. 31(1): 127–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Robertson RD. Noncalculous acute cholecystitis following surgery, trauma, and illness. Am Surg. 1970; 36:610–614 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ternberg JL, Keating JP. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Arch Surg. 1975; 110:543–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thambidorai CR, Shyamala J, Sarala R, et al. Acute acalculous cholecystitis associated with enteric fever in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995; 14(9): 812–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Niderheiser DH. Acute acalculous cholecystitis induced by lysosphatidyl choline. Am J Pathol. 1986; 124:559–563 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker CG, Dubin T, Glenn F. Induction of acute cholecystitis by activation Factor XII. J Exp Med. 1980; 151:81–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Griffen WO, Bivins BA, Rogers EL, et al. Cholecystokinin cholecystography in the diagnosis of gallbladder disease. Br J Surg. 1980; 191:636–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. Postgrad Med. 1995; 98(3): 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barie PS, Fischer E. Acute acalculous cholecystitis. J Am Coll Surg. 1995; 180:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. On A, Choi HJ, Heymen MB, et al. Pediatric Wilson's Disease: presentation and management. Acta Paed Sin. 1997; 38(2): 98–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]