Abstract

Background:

The most frequent wound complication following repair of large incisional hernias is seroma formation, especially when the use of a mesh onlay requires extensive subcutaneous undermining. Treatment options for postoperative seromas include observation for spontaneous resolution, percutaneous aspiration, closed suction drainage, abdominal binders, and sclerosant.

Methods:

A novel technique for treating persistent postoperative seromas is presented herein. This technique involves a 3-puncture minimally invasive approach that can be performed in an outpatient setting. Evacuation of serous fluid and fibrinous debris is followed by argon beam scarification of the seroma cavity lining. Talc slurry is then introduced into the cavity. Three patients have been treated with this technique.

Results:

All 3 patients had successful ablation of seromas that had persisted despite standard treatment modalities.

Conclusion:

A minimally invasive approach is a reasonable and safe alternative for treating persistent postoperative seromas.

Keywords: Incisional hernia, Seroma, Mesh, Laparoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Wound-related complications are common after incisional hernia repair with abnormal fluid collections being the most frequent problem. When mesh is used for repair of larger and more complex incisional hernias, the risk of seroma formation increases. The mesh onlay technique, which requires more extensive dissection, is associated with an even greater incidence of seroma formation.1 Previously reported rates of seroma occurrence with different types of mesh range from 4% to 8% with polypropylene (Prolene, Marlex) grafts and 5% to 15% with ePTFE (Gore-Tex) grafts.2–6 In most instances, these seromas resolve either spontaneously or with the insertion of drains or serial percutaneous aspirations. We report a new minimally invasive technique used for treating refractory postoperative seromas, which has been used successfully in 3 consecutive patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case History 1

A 45-year-old morbidly obese white female underwent an attempted open transabdominal hiatal hernia repair that had to be aborted. She subsequently underwent a successful transthoracic repair. Postoperatively, she developed an incisional hernia, which was repaired with an ePTFE patch. This patch got infected and was removed. The patient predictably developed a recurrent incisional hernia with symptoms of generalized abdominal discomfort, especially with strenuous activity. She was referred to our institution for repair of this hernia.

In March 1999, the patient underwent an attempted laparoscopic incisional hernia repair, which was converted to an open procedure. The hernia was repaired with a “sandwich” technique with a piece of ePTFE patch sutured to the undersurface of the peritoneum and an onlay sheet of polypropylene mesh placed on top of the fascia and below the subcutaneous tissues. Postoperatively, the patient developed a large seroma, which was percutaneously aspirated in the office yielding approximately 2000 cc on 3 occasions (at 3, 8, and 11 months postoperation). The fluid reaccumulated despite the use of an abdominal binder following each aspiration.

Case History 2

A 44-year-old obese white male with a past medical history significant for cirrhosis underwent an emergent splenectomy through a midline abdominal incision for blunt trauma. He subsequently developed an incisional hernia, which was repaired in December 1997 with an onlay of polypropylene mesh. This hernia recurred, and the patient was referred to our institution for repair of an enlarging, symptomatic hernia. In September 1998, he underwent repair of his recurrent incisional hernia via the “sandwich” technique, with an underlay of ePTFE patch and an onlay of polypropylene mesh. Postoperatively, he developed a subcutaneous seroma. This was initially treated with an abdominal binder without success. An abdominal CT scan was performed to ensure that the seroma did not communicate with any ascites from his cirrhosis. The CT revealed a large, well-defined extraabdominal fluid collection with an enhancing rim anterior to the mesh. No ascites was seen.

Subsequent treatment attempts for this seroma included percutaneous closed suction aspiration in the office on 5 occasions (at 3, 11, 13, 15, and 17 months postoperation). He was also taken to the operating room at 4 and 10 months postoperation for incision and drainage of his seroma with instillation of doxycycline as a sclerosant. Despite these attempts, the seroma recurred.

Case History 3

An 80-year-old female underwent an emergent ileo-cecal resection at our institution for obstruction secondary to a stricture from Crohn's disease. Postoperatively, she developed an enlarging lower midline incisional hernia. This hernia was subsequently repaired in April 2000 by primary fascial closure with a suprafascial onlay of polypropylene mesh. She developed a small seroma immediately after the operation that, over the following 5 months of observation, increased in size. At 5 months postoperation, an attempt at percutaneous aspiration in the office followed by the use of an abdominal binder was unsuccessful, and the seroma recurred.

Operative Technique

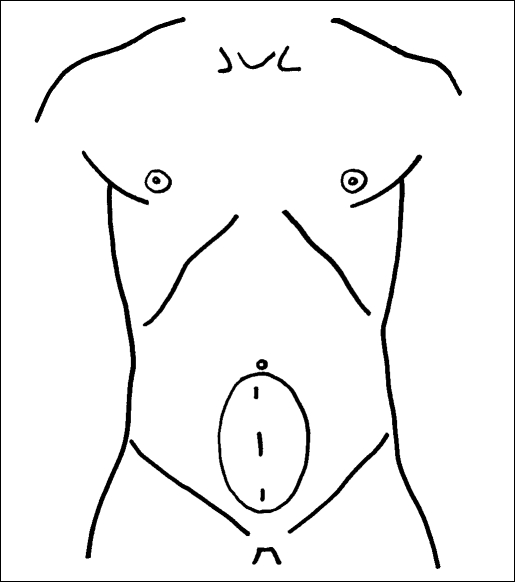

All patients were placed on the operating table in the supine position. The cases were performed with the patient under general anesthesia delivered by laryngeal mask without muscle relaxation. A 3-trocar technique was used. A 5-mm trocar was placed at the superior and at the inferior poles of the seroma cavity in the midline. During the first case, a third 5-mm trocar was placed in the center of the seroma, but this was changed to a 10-mm trocar (Figure 1) for the subsequent 2 procedures.

Figure 1.

Operative placement of laparoscopic trocars. The superior and inferior trocars are 5 mm; the middle trocar is 10 mm.

The serosanguinous fluid was aspirated from the seroma with a suction/irrigator, and the cavity was insufflated with CO2 to a maximum pressure of 12 mm Hg. Significant cellular and acellular debris was found within the cavity (Figures 2 and 3). Pathologic analysis revealed a combination of organizing fibrin clot, hematoma, and fibrous tissue. This debris was removed with a combination of suction and irrigation as well as manual debridement and extraction. The subsequent change to a 10-mm central trocar allowed for open manual extraction through the trocar incision, greatly facilitating this step.

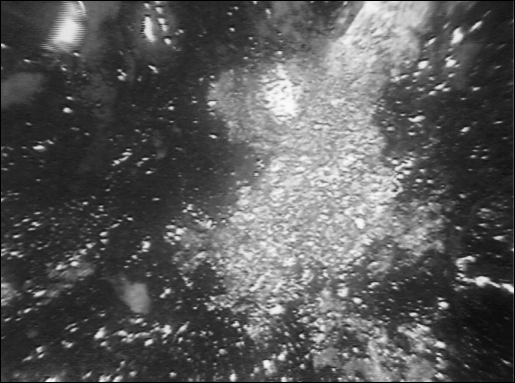

Figure 2.

Operative view of fibrinous exudates, organizing fibrin clot and hematoma encountered inside the seroma cavity.

Figure 3.

Operative view of fibrinous septations within the seroma cavity.

After complete removal of all debris, the cavity was lavaged and checked for hemostasis. An argon beam coagulator was then inserted and used to scarify the entire surface of the seroma cavity lining (Figures 4–6). Internal insufflation pressure was carefully monitored in light of the significant contribution of the argon gas to this pressure. Upon completion of this step, 4 grams of talc slurried in 30 cc of bupivacaine were instilled into the seroma cavity to further promote sclerosis and adhesion and to offer postoperative analgesia.

Figure 4.

Argon beam scarification of the seroma cavity lining.

Figure 5.

Argon beam scarification of the seroma cavity lining.

Figure 6.

Appearance of the seroma cavity wall following argon beam scarification.

The trocars were removed under direct laparoscopic vision, and the seroma cavity was then desufflated. The fascia of the 10-mm trocar site was closed with a single non-absorbable suture, and the skin edges of all 3 trocar sites were reapproximated with subcuticular absorbable sutures. Sterile dressings were applied. The patients were then placed in abdominal binders.

RESULTS

No intraoperative complications occurred, and all 3 patients were discharged home the same day of surgery. Patients 2 and 3 had successful ablation of their seromas with no subsequent reaccumulation of fluid at 6 and 2 month's follow-up, respectively. Patient 1 returned at 6 months postoperatively with a fluid collection, which was drained percutaneously in the office. This fluid has not returned at 3 months since this single aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Repair of incisional hernias is associated with a substantial incidence of postoperative fluid collections. The use of mesh leads to a significantly increased risk of this wound-related complication when compared with simple suture repair. The incidence of postoperative fluid accumulation is highest following procedures where the mesh is placed in a subcutaneous location using an onlay technique. During an onlay procedure, not only are many blood vessels transected during the required wide mobilization of subcutaneous tissue flaps, but also the insertion of foreign material temporarily establishes an effective barrier between the circulatory system of the subcutaneous tissues and that of the deeper parietal layers.7 The end result of these 2 factors is the extrafascial accumulation of serum. Rapid fibrinous fixation of the mesh by the host and a 2-way penetration of blood vessels through the pores of the graft are necessary to eliminate the potential dead space between the mesh and the host tissue if seroma formation is to be avoided.8

Multiple treatment modalities exist for these postoperative seromas. The most conservative of these options is observation for spontaneous resolution. Unfortunately, some persistent fluid collections demand intervention, especially when the seroma is symptomatic. In 1971, Smith 7 described the treatment of recurring accumulation of serum in the abdominal wall as consisting of repeated needle aspirations, external application of mild pressure, or continuous tube drainage, or both. In his experience, local injections of triamcinalone could also expedite the resolution of refractory seromas. In 1993, Waldrep 9 reported on 2 patients in whom seromas with mature fibrous walls developed after mesh repair of a ventral hernia. These seromas were refractory to serial aspirations and eventually required surgical excision of the cyst wall for definitive therapy.

The 3 patients described above suffered from persistent postoperative seromas following incisional hernia repair with onlay mesh placement. Conventional therapies failed to treat these seromas despite multiple attempts. Consideration was given to excising the inflammatory pseudocapsules surrounding the seroma cavities, in a fashion similar to the surgical procedure described by Waldrep.9 Instead of resorting to this open procedure for these patients, we attempted a novel, minimally invasive technique for treating these seromas. This technique can be performed on an outpatient basis, does not disturb the integrity of the hernia repair, results in minimal postoperative pain, and requires only basic laparoscopic skills.

CONCLUSIONS

All 3 patients in this series had successful ablation of their refractory seromas with this technique. Further investigation into this approach to persistent postoperative seromas should be performed. Early evidence shows that this minimally invasive approach is a reasonable and safe alternative for treating persistent postoperative seromas. Long-term follow-up is also necessary for its establishment as the treatment of choice.

Contributor Information

Shannon C. Lehr, Department of Surgery..

Alan L. Schuricht, Department of Surgery..

References:

- 1. White TJ, Santos MC, Thompson JS. Factors affecting wound complications in repair of ventral hernias. Am Surg. 1998; 64: 276–280 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turkcapar AG, Yerdel MA, Aydinuraz K, Bayar S, Kuterdem E. Repair of midline incisional hernias using polypropylene grafts. Surg Today. 1998; 28: 59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Molloy RG, Moran KT, Waldron RP, Brady MP, Kirwan WO. Massive incisional hernia: abdominal wall replacement with Marlex mesh. Br J Surg. 1991; 78: 242–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bauer JJ, Harris MT, Kreel I, Gelernt IM. Twelve-year experience with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene in the repair of abdominal wall defects. Mt Sinai J Med. 1999; 66: 20–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellon JM, Contreras LA, Sabater C, Bujan J. Pathologic and clinical aspects of repair of large incisional hernias after implant of a polytetrafluoroethylene prosthesis. World J Surg. 1997; 21: 402–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chrysos E, Athanasakis E, Saridaki Z, et al. Surgical repair of incisional ventral hernias: tension-free technique using prosthetic materials (expanded polytetrafluoroethylene Gore-Tex Dual Mesh). Am Surg. 2000; 66: 679–682 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Smith RS. The use of prosthetic materials in the repair of hernias. Surg Cl North Am. 1971; 51: 1387–1399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Amid PK, Shulman AG, Lichtenstein IL, Hakakha M. Biomaterials for abdominal wall hernia surgery and principles of their applications. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1994; 379: 168–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waldrep DJ, Shabot MM, Hiatt JR. Mature fibrous cyst formation after Marlex mesh ventral herniorrhaphy: a newly described pathologic entity. Am Surg. 1993; 59: 716–718 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]