Abstract

Objective:

Patients demand that health care and procedures in rural areas be provided by ambulatory surgery centers close to home. However, the reimbursement rate for such procedures in ambulatory centers is extremely low, so a standard classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy procedure needs to be more cost effective to be performed there. Instruments and disposable devices can make up ≥50% of hospital costs for this procedure, so any cost reduction has to focus on this aspect.

Methods:

We identified the 3 most expensive disposable devices: (1) an Endostapler, US $498 and 3 staple reloads, US $179 each; (2) a calibrated uterine resection tool 15 mm for encoring of the endocervical canal, US $853; and (3) a serrated edged macro morcellator for intraabdominal uterus morcellation, US $321, and substituted them using classic conservative surgical techniques.

Results:

From September 2001 to September 2002, we performed 26 procedures with this modified technique at an ambulatory surgery center with a follow-up of 6.7 (2 to 14) months. This modified operative technique was feasible; no conversions were necessary, and no complications occurred. Cost savings were US $2209 per procedure; additional costs were US $266.33 for suture material and an Endopouch, resulting in an overall savings of US $50 509.42. The disadvantage was an increase in operating room time of about 1 hour 20 minutes per case.

Conclusion:

These modifications in the classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy technique have proven to be feasible, safe, and highly cost effective, especially for a rural ambulatory surgery center. Long-term follow-up is necessary to further evaluate these operative modifications.

Keywords: Hysterectomy, Laparoscopy, Cost-effective, Rural health care, Disposable instruments, Economics

INTRODUCTION

Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy (CISH) was first described and performed by Kurt Semm from Kiel, Germany.1 We began utilizing this technique at Fayette Medical Center (FMC), Fayette, Alabama, USA in 1992 and have performed more than 500 CISH procedures since then.2 Fayette Medical Center is a well-equipped primary care hospital in Northwestern Alabama, which is adequately reimbursed for all devices used intraoperatively.

In 2001, a new ambulatory health clinic, Lamar Regional Healthcare Center (LRHC), was opened in the county of Lamar, a previously medically under supplied area in Northwestern Alabama, about 30 miles west of Fayette. It is an ambulatory surgery center with extended diagnostic equipment. Due to its lowered medical service, it is only reimbursed as an ambulatory surgery center and not as a hospital. For example, for hysterectomy, LRHC is only reimbursed about 20% of the amount of that reimbursed at FMC for the CISH procedure.

To meet the demand of patients to undergo surgery near home and without loosing money because of decreased reimbursement, a procedure like CISH had to be modified to avoid expensive disposable devices and to be cost effective.

Therefore, we identified the 3 most expensive disposable instruments and replaced them with classic conservative surgical techniques. The 3 most expensive disposable devices needed for CISH are:

disposable Endostapler ETS (US $498; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) with 3 staple reloads (each US $179; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA);

disposable calibrated uterine resection tool (CURT) 15 mm for encoring of the endocervical canal (US $853; WISAP America, Lenexa, KA, USA); and

disposable serrated-edged macro morcellator (SEMM) 15 mm for intraabdominal uterus morcellation (US $321; WISAP America, Lenexa, KA, USA).

The cost for just these 3 disposable devices is US $2209 per procedure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a first step, we defined classic surgical techniques like coagulation, suturing, and transabdominal scissor morcellation to replace the function of the disposable instruments listed above (Table 1).

Table 1.

Disposable Instruments Replaced With Surgical Technique

| Classic Intrafascial Supracervical Hysterectomy Technique at Fayette Medical Center2 | Outpatient Laparoscopic Hysterectomy Technique at Lamar Regional Healthcare Center |

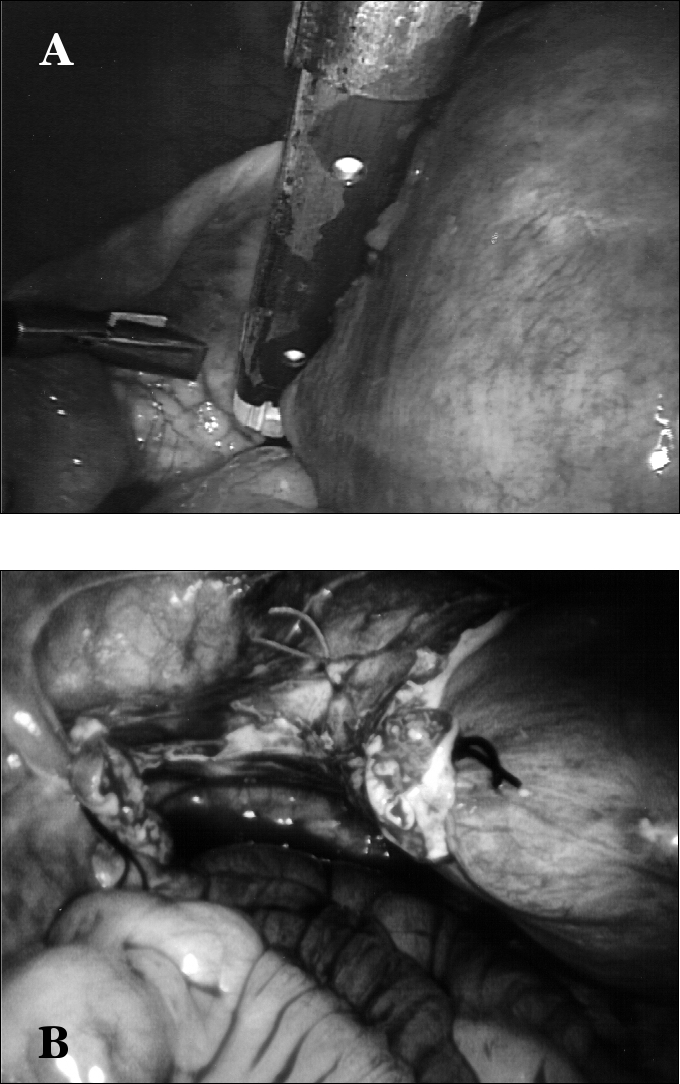

| Endostapler for dissection of uterus from adnexae on both sides (Figure 1A) | Coagulation and extracorporeal or intracorporeal suturing (Figure 1B) |

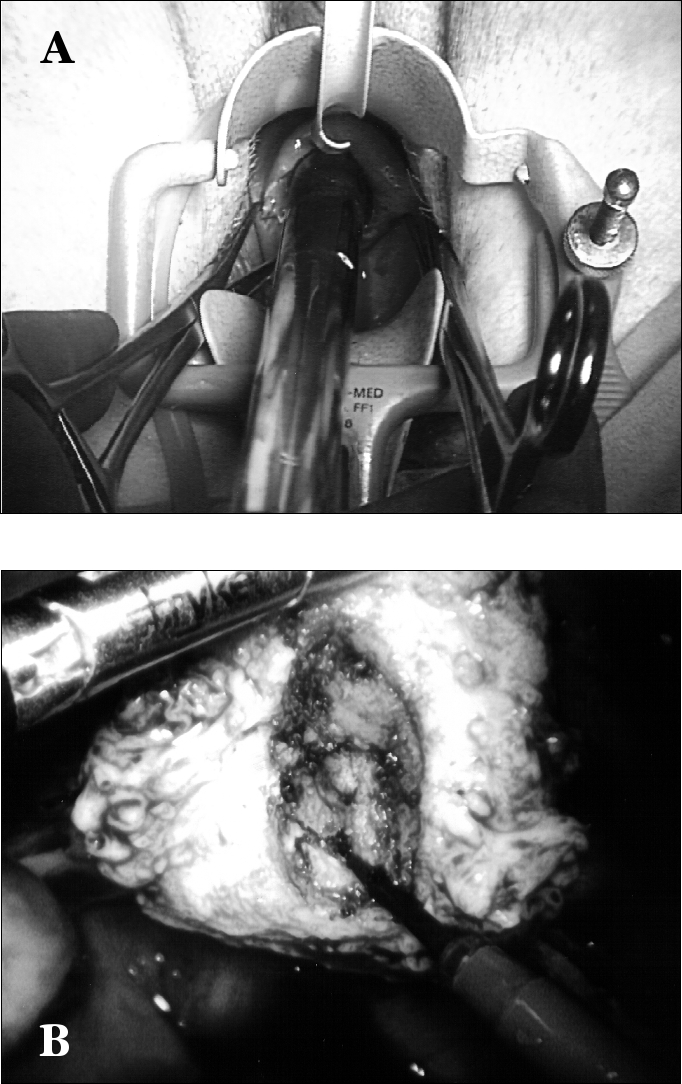

| Coring of the endometrial canal with calibrated uterine resection tool (Figure 2A) | High conization from vagina, additional contraconization of cervical stump from abdomen (Figure 2B) |

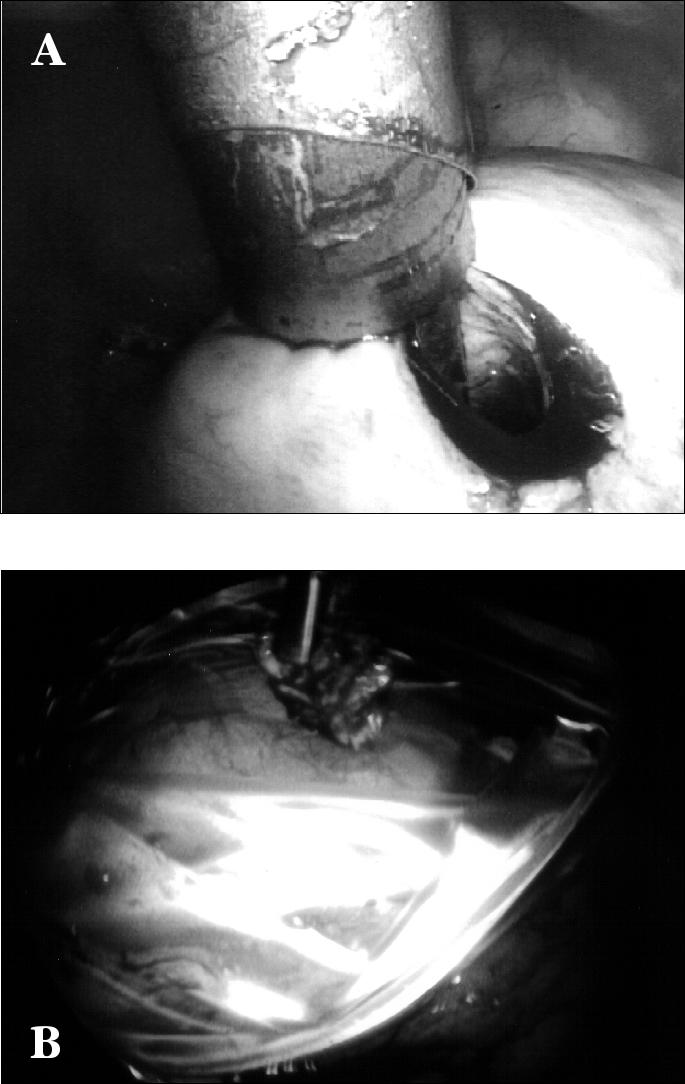

| Intraabdominal uterus morcellation with serrated-edged macro morcellator (Figure 3A) | Endobag removal, transabdominal wall cutting with scissors (Figure 3B) |

In a second step, we used this modified outpatient laparoscopic hysterectomy technique in 26 selected cases and operated without expensive disposable instruments at Lamar Regional Healthcare Center (LRHC), Sulligent, AL, USA. Preoperatively, the patients were told that the procedure could also be done in a distant hospital as a nonoutpatient procedure and that operation time there would be significantly less. All chose to be operated on at LRHC. Patient selection for LRHC was primarily based on the reimbursement availability. For example, Medicare patients were excluded, because Medicare does not reimburse for a hysterectomy at this ambulatory surgery center. Preoperative teaching is required. Postoperatively, all patients were discharged to a caring environment of family and friends. Before discharge, patients had to meet discharge criteria: no nausea, tolerating a diet, ambulating, urinating, and pain controlled with oral analgesia. A nurse and a physician were always available for support via telephone and at LRHC 24 hours 7 days a week in case of postoperative questions or complications.

RESULTS

A retrospective analysis of the first 26 cases from September 2001 to September 2002 was performed. The follow-up time was 6.7 (2 to 14) months. Patient demographics are listed in Table 2. In only 9 patients, this modified technique was used for a laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy alone. In the other 17 cases, 1 (n=14) or 2 (n=3) procedures were added.

Table 2.

Patient Demographics and Operation Statistics for Cost-effective Hysterectomy Technique at Lamar Regional Healthcare Center

| Patients (n) | 26 |

| Age (years) | 42.9 (31–56) |

| Evaluation Period | September 2001–September 2002 |

| Follow-up Time (months) | 6.7 (2–14) |

| Procedures | 46 (1.77 per patient) |

| Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy alone | 9 |

| Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy with additional procedure | 17 |

| Salping- and oophorectomy bilateral | 8 |

| Salping- and oophorectomy unilateral | 4 |

| Vaginal suspension | 4 |

| Cholecystectomy, cystoscopy, femoral hernia repair and lipoma excision | 1 each |

| Operation Time | |

| Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy alone (n=9) | 3 h 14 min (2 h 35 min–3 h 55 min) |

| Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy plus 1 additional procedure (n=14) | 3 h 42 min (2 h 45 min–4 h 55 min) |

| Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy plus 2 additional procedures (n=3) | 3 h 32 min (3 h 10 min–3 h 50 min) |

| Estimated Blood Loss (mL) | 85.2 (15–250) |

| Recovery Room Time (min) | 41.9 (0 h 30 min–1 h 30 min) |

| Time From OR to Discharge (including recovery room time) | 5 h 40 min (2 h 40 min–17 h 10 min) |

Estimated blood loss as well as recovery room times are comparable to those for standard CISH. Due to increased manual operative techniques, the operation time increased even for an experienced surgeon– on average, about 1 hour and 20 minutes per procedure compared with that of a standard CISH with disposable instruments. Despite the significant increase in operative time, the average length of postoperative stay was only 5 hours 40 minutes, making this an outpatient procedure for preselected patients.

Time from the operating room to discharge from the hospital was increased in 2 patients who had prolonged nausea that was anesthesia- or medicine-related. Both patients stayed overnight at LRHC with lengths of stay (LOS) of 16 hours 10 minutes and 17 hours 10 minutes, respectively, after leaving the OR. Without these 2 patients, the LOS would have been 4 hours 45 minutes. No procedure-related postoperative complications occurred. And no readmittance to the hospital was necessary within 30 days after discharge.

The cost comparison is listed in Table 3. The cost savings for not using the disposable instruments is US $2209 per case. An additional cost of US $266.33 is for 1 Endopouch for specimen removal and transabdominal wall dissection with standard scissors in this bag, 3 additional Endoloops used for securing the ovarian vessels and uterine stump, and 2 Ethibond sutures used for suturing the round ligaments to the cervical stump. This leads to absolute savings of US $1942.67 per case and overall savings of US $50 509.42 for all 26 cases performed with this modified operative technique.

Table 3.

Cost Comparison of Disposable Instruments Eliminated and Costs for Substitutes

| Standard CISH* Technique at FMC† | Cost (US$) | Cost-Saving Hysterectomy Technique at LRHC‡ | Cost (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endostapler | 498.00 | 2 Ethibond | 44.33 |

| 3 Stapler reloads (US $179 each) | 537.00 | 1 Endopouch | 108.00 |

| CURT§ | 853.00 | 3 Endoloop | 114.00 |

| SEMM∥ | 321.00 | NA | – |

| Total disposable costs | 2209.00 | Additional costs | 266.33 |

| Savings per case | 1942.67 |

CISH = Classical intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy.

FMC = Fayette Medical Center.

LRHC = Lamar Regional Healthcare Center.

CURT = Calibrated uterine resection tool.

SEMM = Serrated-edged macro morcellator.

Figure 1.

Stapling of the left uterine ligament (A). Alternative: coagulation and suture for uterine dissection (B).

Figure 2.

Encoring of endometrial canal with calibrated uterine resection tool (A). Alternative: high conization vaginally and contraconization intraabdominally with coagulation/monopolar needle (B).

Figure 3.

Intraabdominal uterus morcellation with hand-driven serrated-edged macro morcellator (A). Alternative: manual transabdominal morcellation with scissors and Endobag retrieval (B).

DISCUSSION

The first decade of operative laparoscopy brought the development of many new sophisticated disposable devices and instruments. Conservative classical surgical techniques like suturing and coagulation were replaced with fast but costly disposable instruments. A major drawback emerging with the introduction and development of laparoscopic surgery was the increased cost due to investment in required equipment and the use of disposable instruments.3 These costly disposable devices were helped to improve laparoscopic procedures and opened the way for many new operative applications. Some staplers, for example, can even shorten procedures significantly. But increasing cost pressure and decreased reimbursement as well as the demand for savings by health insurance companies has prompted thoughts about ways to save money. Now the pendulum has swung back and expensive disposable instruments are being replaced by old-fashioned surgical techniques. Although use of disposable instrumentation profoundly influences the cost of laparoscopy,4 it is the surgeon who affects the majority of operating room costs.5 Finally, physicians have the choice of materials,6 so alternatives for expensive disposable laparoscopic equipment are being developed, eg, for the endobag.7–10 Afterall, the costs of disposable laparoscopic instruments should not be used as an argument against laparoscopic procedures in general, because an overall cost comparison of different hysterectomy techniques has shown advantages for laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy techniques vs abdominal hysterectomy for society.11

Cost-effectiveness has become more of an issue, especially for rural ambulatory surgery centers, although they can perform surgery safely, cheaply, and with reduced length of hospital stay.12 Increased costs because of expensive equipment might lead to a shorter hospital stay but are not always reimbursed.3 So, expensive, disposable devices mean savings for society as a whole but result in a financial loss for the hospital, a nonreimbursed increase in hospital costs.6 Costs and benefits have to be evaluated for real overall cost-effectiveness,13 preferably in a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) that covers all aspects not only economic value but also health effects.14

In our view, cost savings in laparoscopy lately have focused too much on robotics and computer-guided surgery and telesurgery. However, although the feasibility of these systems has been proven, such equipment is extremely expensive, the cost savings in contrast to the spending are not obvious but unaffordable for small hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers, not to mention poorer countries in the rest of the world. For most hospitals, a physician and operating room nurses are still cheaper and more flexible than a robotic system even in the USA. So, warnings are published against purely technology inspired investments that entail the risk for over-consumption and inappropriate use.6

However, we have to keep in mind that laparoscopy with expensive disposable instruments is a privilege of the first world and wealthy patients elsewhere. In many parts of the world, such laparoscopic procedures with advanced and expensive equipment are simply not affordable because they are not reimbursed by health insurance companies. Physicians in third world countries even have to face greater cost problems, especially with laparoscopy.

What are the options for cost savings? The following solutions are possible: reusable instruments, reuse of disposable instruments, replacement of laparoscopic instruments with other surgical techniques.

Reusable instruments are more cost effective than are disposable instruments,15 sometimes up to a factor of 10,16 and therefore reusable instruments are strongly recommended.15 So, reducing the cost of laparoscopic hysterectomy by using reusable surgical equipment is possible.17 However, reusable instruments are currently not available for this type of classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy.

Reuse of disposable instruments—which are intended by their manufacturers for single-use only—has been proven to be technically possible and feasible.18 However, drawbacks are that such reuse is “off-label use” and makes the physician technically an instrument manufacturer and responsible and liable for any failure. Cleaning of disposable plastic laparoscopic instruments can be difficult and has been proven to not always be successful.19 Even a residual infectious virus load might be possible.20

So, the decision was made to develop operative alternatives for disposable instruments used in classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomy (CISH), which is a well-established procedure at our institutions.2 This is of special importance because disposable instruments used for this procedure are quite expensive. Due to the opening of a new ambulatory surgery center in the rural area of Northwestern Alabama with a low reimbursement rate from insurance companies, we were forced to develop a more cost-effective operative technique to perform the CISH procedure there. At our institution and in this part of the country, the labor force is rather cheap and available in contrast with expensive equipment, so we substituted the 3 most expensive disposable devices with alternative cost-effective surgical techniques, which are more time consuming.

With the 26 patients presented in this study, we have shown the feasibility of replacing expensive disposable devices with cheap, “old-fashioned” surgical techniques. With a discharge of only 4 hours 45 minutes after the procedure, it was additionally demonstrated that this modified CISH technique is feasible and safe for true out-patient laparoscopic hysterectomy for select patients. Early discharge after laparoscopic hysterectomy has previously been proven feasible.21

Quality first and cost second was the motto of the first decade of operative laparoscopy.5 When quality can be maintained, then a decrease in global costs increases value.5 It is finally up to the physician to increase the value by choosing the adequate technique and equipment. However, we have to keep in mind that in the end quality medical care should not be a matter of cost or resources.22

CONCLUSION

Operative modifications to replace expensive disposable instruments for laparoscopic hysterectomy (CISH) with classic surgical techniques were safe, feasible, and highly cost-effective. Especially for rural clinics with reduced reimbursement rates, such savings can be the key to performing previously expensive laparoscopic procedures with all the costs covered. If the disadvantage of increased operating room time is acceptable, patients can benefit from performance of the procedure close to home and an early discharge from the hospital when family support is available.

Footnotes

Presented as an oral presentation at the 11th International Congress and Endo Expo 2002, SLS Annual Meeting, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, September 10-14, 2002.

Contributor Information

John E. Morrison, Jr., Department of Surgery, Fayette Medical Center (FMC), Fayette, Alabama, USA.; Department of Surgery, Lamar Regional Healthcare Center (LRHC), Sulligent, Alabama, USA.

Volker R. Jacobs, Department of Surgery, Fayette Medical Center (FMC), Fayette, Alabama, USA.; Department of Surgery, Lamar Regional Healthcare Center (LRHC), Sulligent, Alabama, USA. Frauenklinik (OB/GYN), Technical University Munich, 81675 Munich, Germany.

References:

- 1. Semm K. Hysterektomie per laparotomiam oder per laparoskopiam. Ein neuer Weg ohne Kolpotomie durch CASH. [Hysterectomy via laparotomy or pelviscopy. A new CASH method without colpotomy]. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkde. 1991;51(12):996–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrison JE, Jr, Jacobs VR: 437 classic intrafascial supracervical hysterectomies in 8 years. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(4):558–567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fuchs KH. Minimally invasive surgery. Endoscopy. 2002;34:154–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gerry R. Comparison of hysterectomy techniques and cost-benefit analysis. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;11:137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Traverso LW. The laparoscopic surgical value package and how surgeons can influence costs. Surg Clin North Am. 1996;76:631–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vleugels A. Cost-effective management in surgery. The view of the hospital administrator. Acta Chir Belg. 1995;95:211–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chatzipapas IK, Hart RJ, Magos A. The remote control laparoscopic bag: a simple technique to remove intra-abdominal specimen. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(4):622–623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weber A, Vasquez JA, Valencia S, Cueto J. Retrieval of specimen in laparoscopy using reclosable zipper-type plastic bags: a simple, cheap, and useful method. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8(6):457–459 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Erian M, McLaren G. Cost-effective method to laparoscopically retrieve specimens in gynecologic procedures [abstract]. JSLS. 2002;6:231–232 Abstract 215 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mashiach R, Mashiach S, Szold A, Lessing JB. A simple, inexpensive method of specimen removal at laparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(2):214–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simon NV, Laveran RL, Cavanaugh S, Gerlach DH, Jackson JR. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy vs. abdominal hysterectomy in a community hospital. A cost comparison. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:339–345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosen MJ, Malm JA, Tarnoff M, Zuccala K, Ponsky JL. Cost-effectiveness of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11:182–184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brazier JE, Johnson AG. Economics of surgery. Lancet. 2001;358:1077–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Subak LL, Caughey AB. Measuring cost-effectiveness of surgical procedures. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2000;43:551–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Apelgren KN, Blank ML, Slomski CA, Hadjis NS. Reusable instruments are more cost-effective than disposable instruments for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:32–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fengler TW, Pahlke H, Bisson S, Kraas E. The clinical suitability of laparoscopic instrumentation. A prospective clinical study of function and hygiene. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:388–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erian M, McLaren GR, Buck RJ, Wright G. Reducing costs of laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:471–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. DesCoteaux JG, Tye L, Poulin EC. Reuse of disposable laparoscopic instruments: cost analysis. Can J Surg. 1996;39(2): 133–139 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ulualp KM, Hamzaouglu I, Ulgen SK, Sahin DA, Ozturk R, Cebeci H. Is it possible to resterilize disposable laparoscopy tro-cars in a hospital setting? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percut Tech. 2000;10:59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chan AC, Ip M, Koehler A, Crisp B, Tam JS, Chung SC. Is it safe to reuse disposable laparoscopic trocars? An in vitro testing. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1042–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chou DC, Rosen DM, Cario GM, et al. Home within 24 hours of laparoscopic hysterectomy. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1999;39:234–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lambird PA. Resource allocation and the cost of quality. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:1168–1172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]