Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the incidence of port-site metastases in patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures for gynecologic cancers.

Methods:

The charts of patients treated by laparoscopy for diagnosis, treatment, or staging of gynecologic cancers by the academic faculty attending physicians were studied from July 1, 1997 to June 30, 2001. No patient without a histological or cytological diagnosis of cancer from the index procedure were included. Fisher's exact test was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

Eighty-three patients were identified accounting for 87 procedures. Types of cancer treated included endometrial (39), ovarian (29), and cervical (14). Twenty procedures were performed for recurrence of ovarian or peritoneal cancer, and ascites was present in 10 cases. Port-site metastases occurred in 2 patients accounting for 8 sites. Five sites were diagnosed in a single patient 13 days after a second-look laparoscopy for stage IIIB ovarian cancer, and 3 sites were diagnosed in a patient 46 days after an interval laparoscopy for stage IIIC primary peritoneal cancer. Ascites was present in both patients. The overall incidences of port-site metastases per procedure and per port placed were 2.3% (2/87) and 2.4% (8/330), respectively. In patients with a recurrence of ovarian or peritoneal cancer, no port-site metastases (0/16) occurred in the absence of ascites, whereas 50% (2/4) of patients with ascites developed port-site metastases (P<.035).

Conclusions:

The overall incidence of port-site metastases in gynecologic cancers in our study was 2.3%. The risk of port-site metastases is highest (50%) in patients with recurrence of ovarian or primary peritoneal malignancies undergoing procedures in the presence of ascites.

Keywords: Laparoscopy, Cancer, Metastases, Ascites

INTRODUCTION

The first detailed descriptions of the use of laparoscopy in the management and treatment of patients with gynecologic cancers were reported approximately 30 years ago.1–3 Since that time, an increasing number of advanced laparoscopic techniques have been used in the management of gynecologic malignancies including second-look laparoscopy, laparoscopic lymphadenectomy, laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy, and laparoscopically assisted radical vaginal hysterectomy.4–6 Although these techniques generally aim to perform the identical surgery that would be performed through a traditional laparotomy incision, the use of laparoscopy in cancer patients has introduced unique complications and risks in these patients. In particular, an increasing amount of literature describes postoperative tumor growth at the specific puncture sites associated with trocar placement.7 In fact, cases of port-site metastases have been reported involving cancers of the ovary,8–17 cervix,15,18–22 endometrium,23 fallopian tube,24 and vagina16 as well as nongynecologic cancers including stomach, gallbladder, large bowel, liver, pancreas, and urinary tract.7

While the case reports of port-site metastases in patients with gynecologic malignancies continue to accumulate in the literature, the true incidence of this phenomenon has not been clearly defined. For example, 3 studies that have specifically addressed this issue have demonstrated a wide range in reported incidence. Childers et al12 reported port-site metastases in 1 of 88 patients (1.4% per procedure) undergoing a laparoscopic procedure for ovarian cancer and 1% per procedure for gynecologic cancers in general, while Kruitwagen et al13 reported the incidence of port-site metastases to be 16% in patients with ovarian cancer undergoing laparoscopic procedures 9 to 35 days prior to the initial debulking procedure. Finally, van Dam et al17 reported port-site metastases in 9% of patients (9/104) undergoing laparoscopic procedures for primary or recurrent ovarian cancer.

The importance of defining the rate at which port-site metastases occurs has become paramount given the increasing number of gynecologic oncologists who are utilizing laparoscopy in the treatment and management of their patients. Furthermore, if specific risk factors can be identified, this information could be used to help define which patients would most likely benefit from the laparoscopic approach. Therefore, we sought to determine the incidence of port-site metastases in patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures for gynecologic malignancies and to define which patients are at highest risk for the development of this phenomenon.

METHODS

The charts of patients treated by laparoscopy for diagnosis, treatment, or staging of gynecologic cancers by the academic faculty attending physicians were studied from July 1, 1997 to June 30, 2001. Eligible patients were identified by reviewing the fellows' case lists and medical records. No patient without a histological or cytological diagnosis of cancer from the index procedure was included. For the cases identified, charts were reviewed for information regarding the patient's age at the time of the procedure, the date of the procedure, and the types of surgeries performed. Information was also collected on the types of malignancies encountered (including histologic subtypes, grade, stage, and recurrence). The method of laparoscopic entry (ie, direct entry, open entry, or Veress needle entry) was recorded, as well as the number, size, and location of ports at each surgery. Charts were reviewed for the most recent follow-up and for the development of postoperative port-site metastases.

In general, multipuncture operative laparoscopy was performed with the patient under general endotracheal anesthesia by using <15 mm Hg CO2 gas for the creation of a pneumoperitoneum.4 A gynecologic oncology attending physician and a gynecologic oncology fellow were present at each procedure.

All information collected was placed into a computerized database using Microsoft Access 2000 software. Statistical analysis was performed using Fisher's exact test.

RESULTS

Of the 84 patients identified, insufficient information was available on 1 case. Therefore, 83 patients accounting for 87 procedures provided the basis for this study (Table 1). The mean age of patients at the time of surgery was 58 years (range, 38 to 93). Procedures included oophorectomy (n=54), hysterectomy (n=53), and lymph node removal (n=42). Types of cancer treated included endometrial (39), epithelial ovarian (29), cervical (14), sarcomas (uterine or ovarian) (3), metastatic breast (2), fallopian tube (2), and primary peritoneal (1). One patient had a synchronous ovarian and endometrial cancer, and 2 patients had a synchronous ovarian and cervical cancer. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma (n=38) and papillary serous adenocarcinoma (n=27) were the most common histological subtypes noted. Forty-three percent of procedures were performed for grade 3 malignancies, and ascites was present in 10 cases. Laparoscopic entry types included 58 direct entries, 18 open entries, and 11 Veress needle entries. In the 87 procedures, 330 trocar sites were described, and conversion to laparotomy was elected in 18 cases. The average period of follow-up was 361 days (range, 17 to 1282). Port-site metastases occurred in 2 patients accounting for 8 sites as described below.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Cancers*

| Site | Number | Stage I,II,III,IV | Ascites | Port-site Metastases Cases (No.of Sites) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrium | 39 | 32,2,5,0 | 1 | 0 |

| Primary | 37 | 31,2,4,0 | 1 | 0 |

| Recurrent | 2 | 1,0,1,0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ovarian Epithelium | 29 | 6,1,20,2 | 7 | 0 |

| Primary | 10 | 5,1,2,2 | 4 | 0 |

| Recurrent | 19 | 1,0,18,0 | 3 | 1(5) |

| Cervix | 14 | 6,6,0,2 | 2 | 0 |

| Primary | 12 | 6,4,0,2 | 2 | 0 |

| Recurrent | 2 | 0,2,0,0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sarcoma of Uterus or Ovary | 3 | – | 0 | 0 |

| Primary | 1 | – | 0 | 0 |

| Recurrent | 2 | – | 0 | 0 |

| Metastatic Breast | 2 | 0,0,0,2 | 0 | 0 |

| Fallopian Tube | 2 | 1,1,0,0 | 0 | 0 |

| Primary Peritoneum Recurrent | 1 | 0,0,1,0 | 1 | 1(3) |

One patient had a synchronous ovarian and endometrial cancer, and two patients had a synchronous ovarian and cervical cancer.

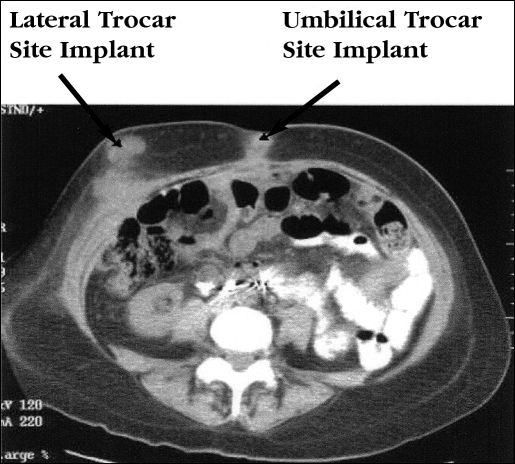

Port-Site Metastases Cases

Patient 1 was a 56-year-old female who had a history of stage IIIC papillary serous, poorly differentiated, primary peritoneal cancer. Her initial staging procedure included an exploratory laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymph node sampling, omentectomy, and optimal debulking. Postoperatively, she received 10 cycles of chemotherapy with paclitaxel and carboplatin. Approximately 11 months after the initial procedure, the patient underwent an open interval laparoscopy, aspiration of ascites, multiple biopsies and partial peritonectomy. This procedure used a 10-mm infraumbilical port, a 5-mm port in the left upper quadrant, a 5-mm port in the right mid abdomen, and 5-mm bilateral lower quadrant ports. Findings at the time of surgery included approximately 1000 mL of ascites and multiple nodules measuring up to 3 mm scattered throughout the abdomen and pelvis. All residual disease at the completion of the surgery was less than 1 cm. Final pathology from this procedure confirmed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma involving peritoneal and omental implants. Postoperatively, the patient began second-line chemo-therapy with liposomal doxorubicin and gemcitibine. Forty-six days after the interval laparoscopy (at the time of the second cycle of chemotherapy), this patient was noted to have abdominal wall metastases at the location of the left upper quadrant, umbilicus, and right mid-abdominal wall. Port-site metastases can be clearly seen on the computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1). The patient was given the option of surgical resection of the tumor prior to radiation treatment, but elected to proceed with radiation therapy alone. She received 3000 cGy of radiation therapy to the affected sites with gradual improvement in the abdominal wall masses noted on clinical examination. Shortly after completing her radiation treatment, the patient transferred her care to Puerto Rico and expired 6 weeks later.

Figure 1.

CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrating port-site metastases at the umbilical and right lateral locations in Patient 1 following a recent laparoscopic procedure.

Patient 2 was a 59-year-old female with a history of stage IIIB poorly differentiated papillary serous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Her initial staging procedure included an exploratory laparotomy, total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, cholecystectomy, sigmoid resection and reanastomosis, and suboptimal debulking (1/4 inch of tumor carpeting the pelvic floor was not removed). Postoperatively, the patient received 6 cycles of topotecan and cisplatin followed by a second-look laparoscopy with multiple biopsies. For this procedure, a Veress needle was placed in the left upper quadrant, and a pneumoperitoneum was created. A spinal needle was used to map the anterior abdominal wall, a clear space was determined just above the umbilicus, and a 5-mm trocar was placed at this position. Five-millimeter trocars were also placed at the suprapubic region, bilateral lower quadrants, and in the left upper quadrant for a total of 5 trocars used in this procedure. Findings at the time of surgery included approximately 150 mL of murky ascites, several small 1-mm nodules studding the diaphragm, and multiple nodules (< 5 mm) lining the pelvic floor and bilateral pelvic sidewalls. At the completion of the procedure, the remaining disease was not greater than 2 mm at its greatest diameter throughout the abdomen and pelvis. The final pathology from this procedure showed adenocarcinoma consistent with ovarian origin involving the vaginal cuff, abdominal wall, and cul-de-sac adhesions. Thirteen days after her second-look laparoscopy, the patient presented with areas of swelling at all 5 laparoscopic incisions consistent with port-site metastases. She was admitted to the hospital for a partial small bowel obstruction, and subsequently underwent an examination under anesthesia, diagnostic laparoscopy, exploratory laparotomy, tumor biopsy, aspiration of ascites, and ileotransverse colon bypass. Findings at the time of surgery included approximately 4 liters of ascites and diffuse carcinomatosis. The rectosigmoid colon was severely attached to the pelvic sidewall, the terminal ileum, and the cecum. Bulky tumor in this area was found to be the cause of the obstruction. Entry into the abdomen was initially accomplished using an open laparoscopic approach, and a second 5-mm trocar was placed in the midline lower abdomen. The ascites was removed, and the decision was made to proceed with a laparotomy via a vertical midline incision to perform a small bowel to trans-verse colon bypass. Postopera-tively, the patient received 8 cycles of paclitaxel, adriamycin, and cisplatin, and remained clinically free of disease for approximately 5 months. She then showed evidence of recurrence and received 4 cycles of liposomal doxorubicin and gemcitibine followed by excision of a right lower quadrant anterior abdominal wall mass. Based on chemosensitivity results performed on the tumor, the patient then received 8 cycles of 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin. She was found to have brain metastases during this treatment, and she died of her disease approximately 3 weeks after her eighth cycle of 5-fluorouracil with leucovorin.

Incidence of Port-Site Metastases

The overall incidences of port-site metastases per procedure and per port placed were 2.3% (2/87) and 2.4% (8/330), respectively. The incidence of port-site metastases per procedure for cancer of the ovary, peritoneum, and fallopian tube was 6.25% (2/32). Twenty procedures were performed for recurrence of ovarian or peritoneal cancer, and the specific characteristics of these cases are summarized in Table 2. Of these 20 procedures, ascites was present in 4 cases. In patients with recurrence of ovarian or peritoneal cancer (Table 3), no port-site metastases (0/16) occurred in the absence of ascites, whereas 50% (2/4) of patients with ascites developed port-site metastases (P<.035).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian and Primary Peritoneal Cancers/Surgical Procedures

| Factor | Number |

|---|---|

| Ascites | |

| Absent | 16 |

| Present | 4 |

| Histological Subtype | |

| Papillary Serous | 18 |

| Clear Cell | 1 |

| Not Available | 1 |

| Grade | |

| 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 3 | 18 |

| Not Available | 1 |

| Entry Type | |

| Direct | 9 |

| Open | 7 |

| Veress Needle | 4 |

| Laparotomy | |

| Yes | 8 |

| No | 12 |

Table 3.

Observed Frequencies of Port-Site Metastases and Ascites in Patients With Recurrent Epithelial Ovarian and Primary Peritoneal Cancers

| Ascites | Port-Site Metastases Absent | Port-Site Metastases Present |

|---|---|---|

| Absent | 16 | 0 |

| Present | 2 | 2 |

DISCUSSION

The overall incidence of port-site metastases in gynecologic cancers in our study was 2.3%. Our results demonstrate that the risk of port-site metastases was 50% in patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures for recurrence of ovarian or primary peritoneal malignancies in the presence of ascites.

The association of ascites with port-site metastases after laparoscopy was initially described in 1978 in a patient with ovarian cancer.8 Since that report, several authors7, 11, 13, 16, 17 have suggested that the presence of ascites may be a contraindication to performing laparoscopy in patients with known or suspected malignancy. Specifically, a review of the literature of all cases of port-site metastases demonstrated the presence of ascites to be significantly associated with the early occurrence of port-site metastases,7 and another study has demonstrated that patients with ovarian cancer who developed port-site metastases after undergoing laparoscopy tended to have larger amounts of ascitic fluid present at the time of surgery.17 Although our numbers are small, our results support the notion that the presence of ascites in patients with known or suspected malignancies may be associated with the development of trocar site metastases postoperatively.

While second-look laparoscopies are being performed more and more frequently in patients with ovarian cancer, the safety of this procedure is still under investigation. Both cases of port-site metastases in our experience occurred in patients after undergoing a second-look or interval laparoscopy, which suggests that patients with recurrent disease may be at a higher risk than patients with primary disease. Although at least 3 cases of port-site metastases following a second-look (or third-look) laparoscopy for ovarian cancer have been reported,12,16,25 over 25 cases of port-site metastases have been reported in the English literature in patients after laparoscopy for primary ovarian cancer.8–11,13–17 It is possible that the number of port-site metastases in patients following interval laparoscopies has been underreported and that as this procedure continues to be more widely accepted, further cases will be identified. We have shown that patients undergoing laparoscopic procedures for recurrence of ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer in the presence of ascites have a significantly higher risk of developing port-site metastases compared with patients without ascites.

Although the concept of tumor cell contamination of the surgical wound was described over 40 years ago,26 the mechanism by which wound metastases occurs is still not completely understood. Several factors related to surgery have been implemented in aiding the spread of cancer cells including accidental incision of the tumor, transection of lymphatic channels that contain cancer, direct dissemination of surface tumors, and even the biological conditions created by the trauma of surgery itself. Many theories have been proposed to account for the ability of tumor to spread to surgical wounds. For example, the tumor cell entrapment hypothesis, which was proposed in 1989, suggests that free cancer cells are able to implant on raw tissue surfaces including damaged peritoneal surfaces.27 Postoperatively, these areas become covered by a fibrinous exudate which could serve to protect the tumor cells from destruction by the normal defense mechanisms. The tumor cell entrapment hypothesis is supported by studies that have demonstrated tumor cells at concentrations of up to 26% in wound washings and have shown the recovery of tumor cells from the gloves and instruments used during surgery.26 Hypotheses specific to laparoscopy include exfoliation and spread of tumor cells by laparoscopic instruments, direct implantation at the trocar site by frequent changes of instruments, direct implantation from the passage of the specimen, the presence of the pneumoperitoneum, which can create a “chimney effect” that causes an increase in the passage of tumor cells at port-sites, and preferential growth of malignant cells at areas of laparoscopic peritoneal perforation.7 Interestingly, a recent case report describes a patient who underwent an exploratory laparotomy with optimal cytoreduction and postoperative platinum-based chemotherapy for stage IIIC ovarian cancer, who later presented with recurrence in an operative incision from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy that had been performed several months prior to her initial cancer diagnosis.28 This case further underscores the complexity of the mechanisms involved in the occurrence of port-site metastases.

Currently, investigators are researching ways to prevent tumor spread during laparoscopy and several clinical reports have suggested that gasless laparoscopy may aid in the prevention of port-site metastases by reducing tumor dissemination created by the CO2 pneumoperitoneum.7, 16, 29 However, in vitro research involving a laparoscopic model performed on colorectal cancer cells showed that malignant cells were not identified in the CO2 exhaust, but were found on the laparoscopic instruments used.30 Similarly, a study of the instruments, tro-cars, and CO2 gas of 12 patients undergoing staging laparoscopy for pancreatic cancer showed extremely low levels of free-floating tumor cells when compared with the cell content found on the trocars and instruments.31 In both cases, the authors concluded that the finding of malignant cells on the ports was a result of direct contamination by the instruments and not from dispersion of malignant cells by the CO2 gas. Finally, in a recent prospective randomized study in rats using a xenograft ovarian cancer model, port-site metastases was found to be significantly higher in the gasless laparoscopy group compared with that in a group that had laparoscopy with a CO2 pneumoperitoneum.32 Whether or not patients with malignancy would benefit from a gasless laparoscopy approach remains controversial and further research is needed in this area.

In addition to the perceived increased frequency of wound metastases to port-sites compared with patients undergoing traditional laparotomy procedures, the vast majority of reported cases suggests a much more rapid recurrence of tumor in patients with port-site metastases. In a study that reviewed the literature for all cases of port-site metastases (including 20 cases involving gynecologic malignancies), the period of time from the procedure to the diagnosis of port-site metastases ranged from 7 days to 3 years, and in general gynecologic cancers had a shorter interval to occurrence than other reported cancers.7 Specific factors that were shown to be significantly associated with the rapid development of port-site metastases postoperatively included the diagnosis of ovarian malignancy, the presence of ascites, and noncurative surgery. Our findings are consistent with those described above as our patients (one with ovarian cancer and one with primary peritoneal cancer) developed port-site metastases at 13 days and 46 days postoperatively after undergoing noncurative procedures in the presence of ascites.

Several studies have suggested possible methods to avoid or decrease the occurrence of port-site metastases in addition to the ways outlined above. The use of intraperitoneal cytotoxic agents at the time of laparoscopy is currently under investigation, and one study33 has shown a significant reduction in port-site metastases when diluted povidone-iodine was instilled in the peritoneal cavity in a rat model. The early onset of postoperative chemotherapy has been advocated by several authors that have suggested that patients with a longer duration between laparoscopy and postoperative chemotherapy may be more likely to develop port-site metastases.14, 15, 17 Irrigation of the port-sites has been recommended7, 12, 14, 17 as well as the use of specimen bags to remove tissues in which malignancy is suspected.17 Authors have suggested that diagnostic or palliative procedures, or both, be avoided, and whenever possible a comprehensive cytoreductive procedure be performed.7, 14, 17 In terms of wound closure, a recent study17 demonstrated fewer cases of port-site metastases in patients that had the wound closed in layers (peritoneum, rectus fascia, and skin) compared with patients who only had the skin closed. Whether any or all of these recommendations prove to help decrease the rate of port-site metastases remains to be seen.

References:

- 1. Bagley CM, Young RC, Schein PS, Chabner BA, Devita VT. Ovarian carcinoma metastatic to the diaphragm-frequently undiagnosed at laparotomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1973;116:397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenoff SH, Young RC, Anderson T, Bagley C, Chabner B, Schein PS, et al. Peritoneoscopy: A valuable staging tool in ovarian carcinoma. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenoff SH, Devita VT, Hubbard S, Young RC. Peritoneoscopy in the staging and follow-up of ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 1975;2:223–228 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nezhat C, Siegler A, Nezhat F, Nezhat C, Seidman D, Luciano A. Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy Principles and Techniques. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jennings TS, Dottino P, Rahaman J, Cohen CJ. Results of selective use of laparoscopy in gynecologic oncology. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;70:323–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dottino PR, Tobias DH, Beddoe A, Golden AL, Cohen CJ. Laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;73:383–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang P-H, Yuan C-C, Lin G, Ng H-T, Chao H-T. Risk factors contributing to early occurrence of port site metastases of laparoscopic surgery for malignancy. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;72:38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dobronte Z, Wittmann T, Karacsony G. Rapid development of malignant metastases in the abdominal wall after laparoscopy. Endoscopy. 1978;10:127–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stockdale AD, Pocock TJ. Abdominal wall metastasis following laparoscopy: a case report. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1985;11:373–375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Miralles RM, Petit J, Gine L, Balaguero L. Metastatic cancer spread at the laparoscopic puncture site. Report of a case in a patient with carcinoma of the ovary. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1989;6:442–424 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gleeson NC, Nicosia SV, Mark JE, Hoffman MS, Cavanagh D. Abdominal wall metastases from ovarian cancer after laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:522–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Childers JM, Aqua KA, Surwit EA, Hallum AV, Hatch KD. Abdominal-wall tumor implantation after laparoscopy for malignant conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;84:765–769 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kruitwagen R, Swinkels BM, Keyser K, Doesburg WH, Schijf C. Incidence and effect on survival of abdominal wall metastases at trocar or puncture sites following laparoscopy or paracentesis in women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:233–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leminen A, Lehtovirta P. Spread of ovarian cancer after laparoscopic surgery: report of eight cases. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:387–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lecuru F, Darai E, Robin F, Housset M, Durdux C, Taurelle R. Port site metastasis after laparoscopy for gynecological cancer: report of two cases. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:1021–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morice P, Viala J, Pautier P, Lhomme C, Duvillard P, Castaigne D. Port-site metastasis after laparoscopic surgery for gynecologic cancer. J Repro Med. 2000;45:837–840 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Da, m P, DeCloedt J, Tjalma W, Buytaert P, Becquart D, Vergote IB. Trocar implantation metastasis after laparoscopy in patients with advanced ovarian cancer: Can the risk be reduced? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:536–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang P-H, Yuan C-C, Chao K-C, Yen M-S, Ng H-T, Chao HT. Squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix after laparoscopic surgery. J Reprod Med. 1997;42:801–804 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Naumann RW, Spencer S. An umbilical metastasis after laparoscopy for squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;64:507–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lane G, Tay J. Port-site metastasis following laparoscopic lymphadenectomy for adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;74:130–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lavie O, Cross PA, Beller U, Dawlatly B, Lopes A, Monaghan JM. Laparoscopic port-site metastasis of an early stage adenocarcinoma of the cervix with negative lymph nodes. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:155–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kohlberger PD, Edwards L, Collins C, Milross C, Hacker NF. Laparoscopic port-site recurrence following surgery for a stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix with negative lymph nodes. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;79:324–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang P-H, Yen M-S, Yuan C-C, et al. Port site metastasis after laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy for endometrial cancer: possible mechanisms and prevention. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bacha EA, Barber W, Ratchford W. Port-site metastases of adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube after laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:1102–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gungor M, Cengiz B, Turan YH, Ortac F. Implantation metastasis of ovarian cancer after third-look laparoscopy. J Pak Med Assoc. 1996;46:111–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thomas CG. Tumor cell contamination of the surgical wound: experimental and clinical observations. Ann Surg. 1961;153:697–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sugarbaker P, Cunliffe WJ, Belliveau J, et al. Rationale for integrating early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy into the surgical treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Semin Oncol. 1989;16:83–97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carlson NL, Krivak TC, Winter WE, Macri CI. Port site metastasis of ovarian carcinoma remote from laparoscopic surgery for benign disease. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;85:529–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schaeff B, Paolucci V. Port site recurrences after laparoscopic surgery. A review. Dig Surg. 1998;15:124–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas WM, Eaton MC, Hewett PJ. A proposed model for the movement of cells within the abdominal cavity during CO2 insufflation and laparoscopy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:105–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reymond MA, Wittekind C, Jung A, Hohenberger W, Kirchner T, Kockerling F. The incidence of port-site metastases might be reduced. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:902–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Agostini A, Robin F, Aggerbeck M, Jais JP, Blanc B, Lecuru F. Influence of peritoneal factors on port-site metastases in a xenograft ovarian cancer model. BJOG. 2001;108:809–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neuhaus SJ, Watson DI, Ellis T, Dodd T, Rofe AM, Jamieson GG. Efficacy of cytotoxic agents for the prevention of laparoscopic port-site metastases. Arch Surg. 1998;133:762–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]