Abstract

Objective:

We compared 2 techniques for performing a partial salpingectomy by using microlaparoscopy and either bipolar coagulation or loop ligation.

Methods:

A 3-mm transumbilical laparoscope with secondary midline port sites midway and suprapubically was used to perform a partial salpingectomy in 109 women desiring permanent sterilization. Each patient was randomly assigned to undergo a tubal resection either after Pomeroy ligation (n=54) or after bipolar coagulation with Kleppinger forceps (n=55). Postoperative pain, as assessed using a 10-point visual analog scale, was the primary comparison endpoint.

Results:

No technical difficulties with either technique required conversion to a minilaparotomy. The mean time to remove both tubal segments was not different between techniques (7 minutes, 21 seconds; range, 4 minutes, 25 seconds to 15 minutes, 43 seconds). Each segment (mean, 1.6 cm; range, 0.8 to 3.5 cm) was confirmed in the operating room, then histologically. Postoperative pain at 6 hours was scored similarly (median, ligation 4.6, coagulation 4.0 of 10). Outpatient recovery was the same, unless pelvic pain required overnight observation (ligation, 4 patients; coagulation, 2 patients).

Conclusion:

Partial salpingectomy, using microlaparos-copy with either bipolar coagulation or loop ligation, was performed with comparable ease, confirmation of the removed tube, and similar postoperative discomfort.

Keywords: Sterilization, Salpingectomy, Microlaparos-copy

INTRODUCTION

Over 170 million couples worldwide use surgical sterilization as a safe and reliable method of contraceptive.1 An estimated 640 000 female sterilization procedures are performed annually in the United States.1 Many women choose laparoscopic techniques as an outpatient means for tubal coagulation or mechanical occlusion. Cumulative 10-year probabilities of pregnancy after bipolar coagulation (54.3/1000 procedures) and after mechanical occlusion (36.5/1000) are higher than failure rates described for postpartum salpingectomies (7.5/1000).2

Female sterilization in which a portion of the fallopian tube is removed offers the theoretical advantage of confirming transection and of reducing failure rates. In addition, the small size of a fascial defect, created by a micro-laparoscopy trocar with a 3-mm diameter rather than a 5-mm or 10-mm diameter, may cause less patient discomfort and less risk of bowel herniation. Two microlaparoscopic techniques have been described to resect a tubal segment either after bipolar coagulation or after ligation of a loop of tube (Pomeroy).3,4 The objective of this randomized surgical trial was to compare the ease and limitations in performing these 2 outpatient techniques for partial salpingectomy.

METHODS

Written approval to undertake this trial was obtained from our hospital Performance Improvement Counsel and Board of Directors. Any patient requesting a tubal ligation was eligible. Assuming that a 50% difference in pain scores at 6 hours between techniques would be clinically important, we calculated a sample size to be 42 in each group for a 90% power and a 5% 2-sided significance level.

All patients were counseled about tubal removal by the microlaparoscopic method, with backup using minilaparotomy for any complication. The surgery would be performed using short-acting general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation. Each patient was also informed about 2 other options that involved standard laparoscopic techniques: bipolar coagulation without salpingectomy and mechanical occlusion alone using Filshie clips.

Enrolled patients were randomized into 2 salpingectomy groups after either bipolar coagulation or Pomeroy ligation groups before salgingectomy. A computer-generated randomization code was prepared by a co-author (WFR), and technique assignment was written on a card placed in the sealed opaque envelope. The next consecutively numbered envelope was opened after obtaining patient consent and once she was transferred to the operating room. Third-year residents in obstetrics and gynecology performed the procedure under direct supervision of the senior author (JCS).

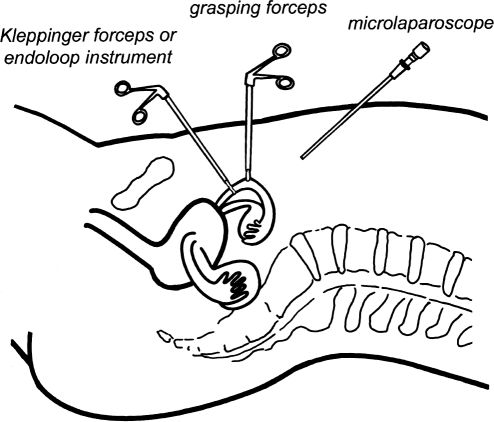

The same microlaparoscopic procedure was performed until the tube was grasped. Placement of the 3 port sites and instruments are illustrated in Figure 1. A small vertical incision (<5 mm) was made deeply just below the umbilicus. A 3-mm trocar was passed into the abdominal cavity to create a pneumoperitoneum by insufflating with carbon dioxide. The 3-mm laparoscope was inserted through the same incision after placement of a trocar sleeve. The patient was placed in a Trendelenberg position, and a second midline port (5 mm) was created suprapubically. Subsequently, a 3-mm trocar was inserted through the midline abdominal wall approximately 8cm above the pubis. Each fallopian tube was visualized. No local anesthetics were applied at the portal sites or at the tubal ligation site. Any adhesions near the tubes were lysed with sharp dissection. A partial salpingectomy was then performed following either bipolar coagulation or Pomeroy ligation.

Figure 1.

Placement of port sites for the 3-mm laparoscope subumbilically, grasping forceps midway, and either Kleppinger forceps or endoloop instrument suprapubically.

Bipolar Coagulation

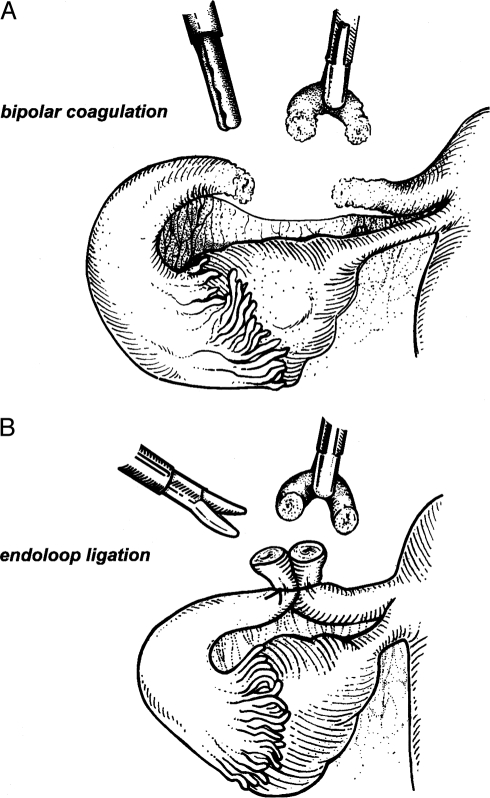

The ampullary-isthmic portion of the tube was grasped using a rigid endoscopic grasper inserted through the midway trocar site. The surgical assistant elevated the tube under tension. Kleppinger bipolar forceps were inserted through the suprapubic trocar. The surgeon then cauterized the proximal portion of the tube, approximately 2 cm from the uterine cornua using 25 W of cutting current.4 An ammeter was used to ensure adequate desiccation. This cauterized segment of the tube was transected using laparoscopic scissors inserted through the same suprapubic trocar. The tube was then cauterized and transected in the same fashion approximately 3 cm distally. The mesosalpinx between the 2 incision sites was then cauterized, and the tubal segment was excised completely (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A microlaparoscopically directed partial salpingectomy involves either coagulating the proximal and distal mid-portion of the tube (A) or a loop of suture placed around the base of a loop of fallopian tube (B). The operative site should be reinspected for transected edges of the tubal segments and for hemostasis of the mesosalpinx.

Pomeroy Ligation

An 18-inch 0-chromic endoloop suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) was inserted into the pelvic cavity through the suprapubic port. The endoscopic grasper, inserted through the midway trocar site, was passed through the endoloop to grasp the ambulatory-isthmic portion of each tube. As the assistant elevated the tube, the surgeon slowly closed the endoloop around approximately 2 cm to 3 cm of the tube, then cut the remaining suture. The loop of tube above the suture was resected using scissors passed through the suprapubic trocar (Figure 2).

Using either technique, the assistant elevated the tube toward the midline, well away from the bladder, intestine, and pelvic sidewall. A 1-cm to 2-cm segment of resected tube was removed from the abdomen under direct visualization with an endoscopic grasper through the suprapubic site. The operative site was re-inspected for hemostasis and, if necessary, was cauterized with the Kleppinger forceps passed through the suprapubic site.

The same procedure was preformed on the contralateral fallopian tube. Both specimens were inspected and, if desired, cannulated with a lacrimal probe to assure adequacy of resection. All instruments were then removed, and carbon dioxide gas was expelled from the abdominal cavity. We did not suture any port site; instead, a bandage was placed over the skin. The tubal specimens were sent for histologic confirmation.

We observed that moderate discomfort is encountered shortly after a laparoscopic ligation. A hand-held 10-point visual analogue pain score (from 0=no pain to 10=excruciating pain) was used for the patient to assign a pain score at 6 hours and at 14 days postoperatively. Preliminary work indicated that a median pain score of 5 was found commonly with the ligation technique at 6 hours postoperatively. Secondary measurable endpoints were additional, operative time (from grasping the tube originally to removing the tubal segment), mesosalpingeal tears, length of tubal segment removed, and preference by each resident physician.

Data were reported either as a mean percentage or as a mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons between the 2 techniques were conducted with either chi-square analysis, the Student t test, or Mann-Whitney analysis where appropriate. Comparisons were made using a Graph Pad InStat, Version 3 program (San Diego, CA). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

All 109 eligible women consented to this investigation between July 1999 and June 2001. Eighty-nine patients underwent microlaparoscopic sterilization only. Twenty patients underwent other planned procedures that included lysis of adhesions (8 patients), ovarian cystectomy (5 patients), cholecystectomy (3 patients), myomectomy (2 patients), or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) procedure of the cervix (2 patients). These additional procedures were conducted before the salpingectomy.

The patients were randomized either to the tubal coagulation group (55 patients) or to the ligation group (54 patients). The patients' ages averaged 30.2 years (range 22 to 42). Patients weighed more in the coagulation group than in the ligation group (163 pounds vs 183 pounds, P<0.05). The racial distribution was 83% non-Hispanic white, 11% African American, and 6% other. Twenty women had prior abdominal operations (ligation 8, coagulation 12).

Visualization through the 3-mm laparoscope was adequate in all cases. Adhesions were recorded as being severe in 6 ligation cases and in 4 coagulation cases. Each tube was identified, and a segment was removed without need for a minilaparotomy. No differences were found between groups in the time to remove the tube and in the length of the tube removed. The mean cumulative time to perform the procedure was 7 minutes, 50 seconds (range: 4 minutes, 15 seconds to 15 minutes, 38 seconds) in the ligation group and 6 minutes, 47 seconds (range: 4 minutes, 26 seconds to 16 minutes, 3 seconds) in the coagulation group. The mean length of removed tubal segment measured 1.6 cm (range: 0.8 to 3.5). A full cross-section of the tubes was identified grossly and confirmed histologically in all patients.

Injury at puncture sites or inadvertent coagulation of vital structures was not observed. The minimal mesosalpingeal bleeding (<5 mL) in 9 patients (ligation 4, coagulation 5) was attributable to release of adhesions rather than to the salpingectomy. Successful hemostasis with the Kleppinger forceps required <1 additional minute.

Pain at incision sites or in the pelvis was described by the patient as being usually mild or moderate 6 hours postoperatively (mean score: 4.6 out of 10 for ligation, 4.0 of 10 for coagulation) except in 6 patients (ligation 4, coagulation 2) that required overnight admission for parenteral morphine or meperidine. Patients requiring mesosalpingeal cautery were not at greater risk for additional postoperative pain. By 14 postoperative days, 2 patients in the ligation group and none in the coagulation group described having persistent mild pelvic pain (score 2 or 3 of 10).

The 3 small portal sites healed well in all cases and were barely visible at the 6-week postoperative visit. No known pregnancies were reported to our office during the postoperative 24 to 48 months.

Each senior resident performed either technique on at least 4 occasions. The additional time to perform the surgery was not statistically shortened between the first and final case. Visualization through the 3-mm laparo-scope did not impair the surgery. Each resident confirmed removal of the tube on gross inspection. None preferred either technique by the end of each 11-week rotation.

DISCUSSION

Female tubal sterilization is the most common form of birth control in the United States.6 We describe in the current study 2 microlapascopic sterilization techniques that may carry a lower failure rate because of removal rather than occlusion of a mid-tubal segment. Both techniques were easy to perform by resident physicians as supervised by the primary author. Neither technique required more time nor led to removal of less fallopian tube. Each technique had its own advantages and limitations.

Use of bipolar, rather than unipolar, coagulation should limit the risk of thermal intestinal injury.7 Our experience with 115 patients, reported here and previously, revealed no technical difficulties.4 Removal of the tube segment was accompanied with varying degrees of thermal artifact and a nearby loss of cellular detail. It was, however, possible to verify removal of a complete portion of fallopian tube in all cases. Separation of the remaining proximal and distal tubal segments simulated a partial salpingectomy that is performed customarily at the time of a cesarean delivery. Separating the exposed tubal edges by at least 2.5 cm may lead to a very low failure rate similar to the failure rate with a Parkland salpingectomy (2.5/1000 procedures).8

The noncautery ligation technique using an endoloop suture was described by Murray et al3 in 28 participants and by Hibbert et al9 in 38 subjects. Those investigators removed a slightly shorter mean tubal segment (1.3 cm rather than 1.6 cm). Compared with the coagulation technique, more room in the pelvic cavity is necessary to apply the endoloop around the base of the elevated tube than to cauterize the tube by using bipolar coagulation. This requirement for additional pelvic space was unimportant unless adhesions prohibited mobility of the tube. When visualization of the elevated tube was unobstructed, the ligation technique required slightly less time than the coagulation technique although this difference was not statistically significant.

Mesosalpingeal bleeding in 10% of cases was attributed to sharp dissection of adhesions rather than to the salpingectomy alone. Additional precautions to minimize the risk of bleeding included placing the scissors tips either within the cauterized area or well above the endoloop suture. Kleppinger forceps were on the operating room table for either technique to coagulate any bleeding sites.

Both techniques permitted gross confirmation of the removed tube segment by our residents.10 The only additional cost associated with either technique was histologic confirmation of the tubal segments. We consider this additional charge ($60 by our pathology service) to be worthwhile, when viewed from a liability perspective in the case of a sterilization failure.

This investigation was not intended to review the contraceptive efficacy of these sterilization techniques, because the small number of patients was only followed up for 48 months postoperatively. Separation of tube segments with the bipolar coagulation technique may be more desirable when one considers the possibility of spontaneous reanastamosis or fistula formation when crushed tubal segments with the ligation method heal in close proximity to each other. It should also be appreciated that surgical reversal is less possible with removal of longer tubal segments. Either salpingectomy technique is, therefore, not usually recommended in women who are either young or of low parity.

Findings from this randomized surgical trial are promising. Either procedure is technically feasible without adding much additional time to remove the tubal segment. Use of smaller-diameter instruments avoids the need for incisional closure and leads to the formation of very small scars at the port sites. Pain from the 3 puncture sites and from partial salpingectomy was usually well tolerated. More experience is necessary to report the incidence of less common complications (such as injury to nearby pelvic structures or need for laparotomy) and to confirm our suspicion that the failure rate is lower with a partial salpingectomy than with tubal occlusion alone.

Footnotes

Presented at the 10th International Congress and Endo Expo 2001, SLS Annual Meeting, New York, NY, December 5– 8, 2001

References:

- 1.Sterilization. Am Coll Obstet Gynecol Tech Bull. 1996;222: 1–3 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peterson HB, Zhisen X, Hughes JM, Wilcox LS, Taylor LR, Trussell T. The risk of pregnancy after tubal sterilization findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;194:1161–1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murray J, Hibbert ML, Heth SR, Letterie GS. A technique for laparoscopic Pomeroy tubal ligation with endoloop sutures. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:1053–1055 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Siegle JC, Cartmell LW, Rayburn WF. Microlaparoscopic technique for partial salpingectomy using bipolar electrocoagulation. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:632–636 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kleppinger RK. Laparoscopy tubal sterilization. In: Garcia CR, Mikuata JJ, Rosenblum NJ, eds. Current Therapy in Surgical Gynecology. Philadelphia, PA: BC Decker; 1987:80–86 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peterson LS. Contraceptive use in the United States: 1982–90. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1995. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics, No. 260 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Soderstrom RM, Levy BS, Engel T. Reducing bipolar sterilization failures. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;74:60–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cunningham FG, Gant NF, Leveno KJ, Gilstrap LC, Hauth JC, Wenstrom KD, eds. Sterilization In: Williams Obstetrics. 21st ed New York, NY: McGraw-Hill;2001:1557 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hibbert ML, Buller TL, Seymour SD, Poore SE, David GD. A microlaparoscopic technique for Pomeroy tubal ligation. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:249–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stovall TG, Ling FW, O'Kelley KR, Coleman SA. Gross and histologic examination of tubal ligation failures in a residency-training program. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;76:461–465 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]