Abstract

Background:

Extragenital endometriosis is an uncommon condition that can affect almost any organ system and tissue in the human body. Disease involving multiple distant sites is extremely uncommon.

Methods:

We report a rare case of synchronous rectovaginal, urinary bladder, and pulmonary endometriosis. We performed a Medline literature search using keywords “endometriosis,” “rectovaginal,” “pulmonary,” “bladder,” “ureteral,” “bowel,” “extrapelvic,” and “extragenital” and were unable to find any prior case reports of such findings. A 31-year-old female presented with catamenial dysuria of 1-year duration, pleurisy associated with spontaneous pneumothoraces of 7 months' duration and a long-standing history of pelvic pain. A multispecialty team with experience in endoscopic techniques was assembled, consisting of a thoracic, a urologic, and a gynecologic surgeon. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with fulguration of all visible pleural endometriosis and pleurodesis was performed, followed by laparoscopic segmental bladder wall endometrioma excision and resection of rectovaginal endometriosis. Twelve months after surgery and without additional hormonal treatment, the patient is symptom free.

Conclusion:

Extragenital endometriosis may coexist in multiple sites. A high index of suspicion aids in the diagnosis. A multidisciplinary approach in a tertiary center, followed by appropriate surgical eradication of visible disease, can successfully treat endometriosis even in such extreme cases.

Keywords: Thoracoscopy, Laparoscopy, Endometriosis

INTRODUCTION

Extrapelvic or extragenital endometriosis has been described in the literature as occurring in almost every organ system.1 However, synchronous multiple site extragenital endometriosis remains a rarity with only one case described of a patient with both ureteral and pulmonary endometriosis.2 Barnes3 described the first case of pulmonary endometriosis in 1953. Endometriosis of the urinary bladder was first reported in 1921 by Judd.4

Rectovaginal septum endometriosis has been reported in the literature to occur in much greater frequency, and it is now considered a variant of deep infiltrating endometriosis.5

In this article, we describe the diagnostic approach and surgical management of a unique case of synchronous, rectovaginal, urinary bladder, and pulmonary endometriosis.

CASE REPORT

A 31-year-old Gravida 0, Caucasian female presented with complaints of catamennial dysuria of 1-year duration, catamennial pleurisy associated with spontaneous pneumothoraces of 7-month duration and a longstanding history of pelvic pain and endometriosis.

The patient reported severe dysuria with her menstrual periods, of almost 1-year duration. She had no incontinence and no voiding dysfunction during the remainder of her menstrual cycle. She had been evaluated previously by 2 gynecologists, who treated her with antibiotics for suspected urinary tract infection. Meanwhile, 7 months prior to presentation and in addition to cyclic dysuria, she suffered the first episode of shortness of breath and pain with inspiration at the onset of her menses. Evaluation at that time in the emergency room including a chest radiogram, revealed a 10% apical pneumothorax on the right lung. She was managed conservatively and was referred to a thoracic surgeon for follow-up. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) pleurodesis was recommended should the episodes recur. The patient did in fact experience 3 additional episodes of spontaneous pneumothoraces, 2 of which happened with menses, and VATS blebectomy and pleurodesis was eventually performed at that time with a presumed diagnosis of catamenial pneumothorax. Following VATS, continuous oral contraceptive pills were prescribed, but the patient suffered 4 more episodes of mild, spontaneous pneumothoraces, managed conservatively. The patient was finally referred to us for further evaluation, with ongoing catamennial urinary, thoracic, and pelvic symptoms.

Her gynecologic history was notable for endometriosis diagnosed and treated laparoscopically in 1993. At that time, cul-de-sac obliteration, rectovaginal space nodularity, and endometriosis of the pelvic peritoneum and vesicouterine fold were found. Visible endometriosis was excised and anatomy was restored. She enjoyed a 9-year symptom-free hiatus. She had never used GnRH agonists. She had never attempted to become pregnant. Her pap smears have been within normal limits, and her menses regulated by a 9-year use of oral contraceptive pills. Her medical history included mild, intermittent asthma and a benign heart murmur. Family history was significant for maternal breast cancer but was negative for endometriosis. The patient was sexually active despite worsening dyspareunia and pelvic pain.

Her general physical examination including lungs was essentially noncontributory. Speculum examination however, was notable for a blue-purple lesion at the posterior fornix. During bimanual and rectovaginal examination, marked uterosacral ligament and rectovaginal septum nodularity and tenderness were noted. No distinct masses could be appreciated.

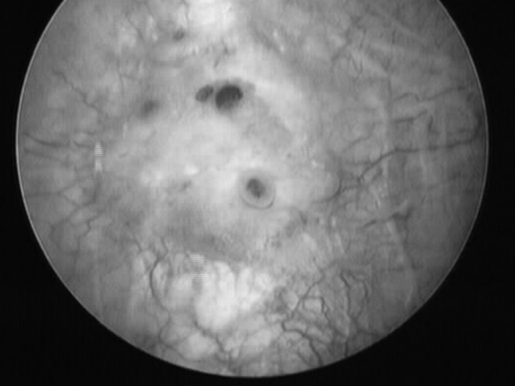

A transvaginal sonographic evaluation of the rectovaginal space and adnexae was suboptimal due to patient discomfort. A transabdominal ultrasound with a distended bladder revealed a mass on the bladder wall measuring 3.5 × 3.5 cm. Office cystoscopy was then performed. It confirmed a 3-cm lesion with edema and purplish highlights located at the dome of the bladder, suspicious for endometrioma (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Endometrioma infiltrating the dome of the bladder.

After careful evaluation of the patient's medical records and taking under consideration (1) the history of endometriosis; (2) the cyclic episodes of pneumothoraces, previously failed VATS-pleurodesis and failed continuous oral contraceptive pills; (3) the highly suspicious mass on the bladder wall; (4) the rectovaginal/cul-de-sac nodularity and vaginal nodule present; and (5) the cyclic incapacitating pelvic pain and dysuria, our team including a urologic, a thoracic, and a gynecologic surgeon decided to take the patient to the operating room for a repeat VATS pleurodesis and laparoscopic excision of suspected bladder and pelvic endometriosis.

Preoperative evaluation included a mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation, routine laboratory results, and anesthesia consultation including a spirometric evaluation that showed evidence of mild obstruction.

VATS of the right lung was performed first. Multiple small lesions were present on the apical region of the lung typical of peritoneal endometriosis (Figures 2 and 3). The lesions were fulgurated using bipolar electrocautery.

Figure 2.

Endometriotic implants on the visceral pleura of the right lung.

Figure 3.

Endometriotic implants on the parietal pleura of the right hemi-thorax.

These findings confirmed the clinical suspicion of pleural endometriosis. The procedure was terminated with pleurodesis and placement of a chest tube.

A bimanual and rectovaginal examination with the patient under anesthesia was then performed. It was positive for uterosacral and rectovaginal septum nodularity. The uterus was partially fixed and retroverted. No palpable masses were found. A 2-cm purple lesion at the posterior fornix consistent with vaginal endometrioma was present.

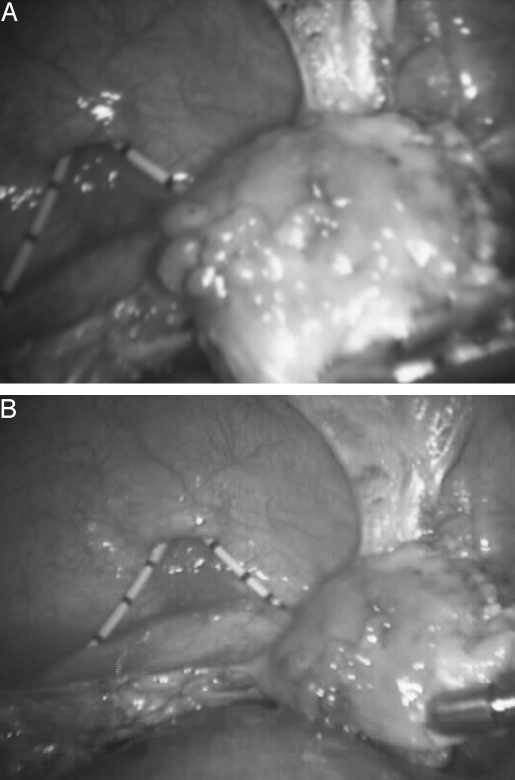

Laparoscopic inspection of the abdominal-pelvic cavity revealed complete cul-de-sac and vesicouterine fold obliteration. The left ovary contained a small endometriotic cyst. The right ovary, appendix, small bowel, cecum, omentum, liver surface, stomach, and diaphragm were macroscopically uninvolved. Extensive lysis of adhesions using the CO2 laser and scissors was performed first. Segmental bladder wall excision and repair (Figures 5 and 6) followed.

Figure 5.

Circumferential excision of the involved bladder dome. Two 6 F stents are seen entering the bladder through the urethra.

Figure 6.

Repaired bladder. The defect was approximated in two layers with slow absorbable Polyglactin sutures.

Figure 4.

Endometrioma with surrounding fibrosis invading the bladder dome and protruding in the bladder mucosa.

Surgery was completed with rectovaginal space entrance, “shaving” the lesion off the rectal wall and excision of the involved posterior fornix (partial posterior vaginectomy).

The patient went in good condition to the recovery room with a chest tube and an 18 F Foley catheter. After a 36-hour hospital stay during which the chest tube was removed, the patient was discharged home with the Foley catheter and oral analgesics. No hormone treatment was added.

A week later, the patient returned for a follow-up visit at the urology clinic. The catheter was removed and she had a successful voiding trial.

The patient had no complaints at the routine postoperative check 2 weeks after surgery. The review of systems was negative for the first time after 1 year of distressing symptoms.

Eight months postoperatively, the patient returned for an office visit. She was having spontaneous menses with no pelvic pain or other associated bladder and pulmonary symptoms. At 12-month follow-up, she remains asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

Since the first case report of thoracic endometriosis, more than 150 cases have been reported in the literature. Fifty percent to 80% of patients with thoracic endometriosis have coexisting pelvic endometriosis.1,6 The prevalence of thoracic endometriosis in women with pelvic endometriosis remains to be established. Pulmonary endometriosis is either pleural (as in this case) or bronchopulmonary (parenchymal) with the former being far more common and presenting most often with pneumothorax, hemothorax, or both. Bronchopulmonary endometriosis tends to present most commonly with hemoptysis. The right hemi-thorax is involved in 90% to 95% of all cases. The diagnosis is usually made clinically because the radiologic findings are often nondiagnostic. Additionally, histologic confirmation is present only in a third of reported cases.1

Urinary tract endometriosis is more common with an estimated prevalence of 1% to 4% of patients with pelvic endometriosis.7,8 The urinary bladder is the most commonly affected organ of the urinary tract. A history of catamenial hematuria, dysuria, urgency, and suprapubic pressure and pain is the usual presentation. It is important to remember that urinary tract endometriosis, especially of ureteral involvement, may present with vague nonspecific symptoms, such as cyclic or continuous back pain, flank pain, and cyclic microscopic hematuria.5 A urinalysis and culture should be performed in all patients to rule out a urinary tract infection. With persistent symptoms, a trans-abdominal ultrasound with a full bladder is very helpful in evaluating the bladder wall and can be used in the initial workup.9 For suspected full-thickness lesions with intravesical protrusion, a cystoscopy (preferably with biopsy), performed during menses can establish the diagnosis.10 Treatment of urinary tract endometriosis requires surgical resection of the involved bladder wall11–13 or affected ureteral segment.5,14 Pulmonary endometriosis presents more challenges in diagnosis and management. After differentiating between bronchopulmonary and pleural endometriosis, treatment may be either surgical or medical. In this case, the presence of spontaneous pneumothoraces and absence of hemoptysis indicated that endometriosis was pleural. During VATS, typical endometriotic lesions were visualized. In the absence of specific guidelines for the management of pulmonary endometriosis, it is reasonable to fulgurate all visible lesions seen during the procedure and then perform pleurodesis. Pleurodesis is the technique of obliteration of the pleural space and can be accomplished with instillation of chemicals, direct radiation or by surgery as in thoracoscopy (VATS). It is indicated in a variety of pleural diseases including recurrent pneumothorax. In this case, the patient failed 1 previous VATS pleurodesis where these lesions had not been directly treated (ie, fulgurated, coagulated).

According to Joseph et al6 surgical pleurodesis was superior to oral contraceptives or danazol in recurrence rates of pneumothorax, hemothorax, or both, in a review of 110 cases of pulmonary endometriosis. Our patient failed continuous oral contraceptive pills and 1 VATS pleurodesis. Subsequently, she responded to a second pleurodesis and ablation of visible endometriotic implants.

Nonaccessible or nonvisible lesions, as in cases of bronchopulmonary endometriosis, may be managed with GnRH analogues.15–21

Rectovaginal endometriosis is best treated surgically.5,22 Excision of the rectovaginal lesion followed by assessment of rectal wall integrity with rigid sigmoidoscopy is the best treatment option for debilitating rectovaginal involvement as with this patient.23

We performed a thorough literature search but were unable to find any prior case reports with this triad of findings to date.

Contributor Information

Georgios E. Hilaris, Center For Special Minimally Invasive Pelvic Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center..

Christopher K. Payne, Department of Urology, Stanford University Medical Center..

Joelle Osias, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Stanford University Medical Center..

Walter Cannon, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center..

Camran R. Nezhat, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Stanford University Medical Center..

References:

- 1. Jubanyik KJ, Comite F. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1997;24(2):411–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ludwig M, Bauer O, Wiedemann GJ, Diedrich K. Ureteric and pulmonary endometriosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2001; 265(3):158–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnes J. Endometriosis of the pleura and ovaries. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1953;60:823–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Judd ES. Adenomyomata presenting as a tumor of the bladder. Surg Clin North Am. 1921;1:1271–1278 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nezhat CR, Berger GS, Nezhat FR, et al. Endometriosis, Advanced Management and Surgical Techniques. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joseph J, Sahn SA. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: new observations from an analysis of 110 cases. Am J Med. 1996; 100(2):164–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moore JG, Hibbard LT, Growdon WA, Schifrin BS. Urinary tract endometriosis: Enigmas in diagnosis and management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;134:162–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bergqvist A. Extragenital endometriosis. A review. Eur J Surg. 1992;158(1):7–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aldridge KW, Burns JR, Singh B. Vesical endometriosis: a review and 2 case reports. J Urol. 1985;134(3):539–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitman GJ, McGovern FJ. Endometriosis of the bladder detected by pelvic ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1994; 13(2):155–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Comiter CV. Endometriosis of the urinary tract. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29(3):625–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nezhat CR, Nezhat FR. Laparoscopic segmental bladder resection for endometriosis: A report of two cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:(5 pt 2):882–884 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nezhat C, Malik S, Osias J, Nezhat F, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic management of 15 patients with infiltrating endometriosis of the bladder and a case of primary intravesical endometrioid adenosarcoma. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:872–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Green B. Laparoscopic treatment of obstructed ureter due to endometriosis by resection and ureteroureterostomy: a case report. J Urol. 1992;148:865–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. L'huillier JP, Salat-Baroux J. A patient with pulmonary endometriosis. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2002;58(4 pt 1):233–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matalliotakis IM, Goumenou AG, Koumantakis GE, Neonaki MA, Koumantakis EE, Arici A. Pulmonary endometriosis in a patient with unicornuate uterus and noncommunicating rudimentary horn. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(1):183–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kuo CH, Tsai EM, Chou CI, Chen HS, Su JH. Kaohsiung: A case of pulmonary endometriosis–a rare case report and a successful treatment experience. J Med Sci. 2001;17(5):278–281 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koizumi T, Inagaki H, Takabayashi Y, Kubo K. Successful use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist in a patient with pulmonary endometriosis. Respiration. 1999;66(6):544–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morita Y, Tsutsumi O, Taketani Y. Successful hormonal treatment of pulmonary parenchymal endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59(1):61–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akal M, Kara M. Nonsurgical treatment of a catamenial pneumothorax with a Gn-RH analogue. Respiration. 2002;69(3): 275–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Perrotin C, Mussot S, Fadel E, Chapelier A, Dartevelle P. Catamenial pneumothorax. Failure of videothorascopic treatment. Presse Med. 2002;31(9):402–404 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Luciano AA, Siegler A, Metzger DA, Nezhat C. Operative Gynecologic Laparoscopy –Principles and Techniques. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nezhat C, Nezhat F, Pennington E. Laparoscopic treatment of infiltrative rectosigmoid colon and rectovaginal septum endometriosis by the technique of videolaseroscopy and the CO2 laser. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;99:664–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]