Abstract

Objectives:

Laparoscopic management of adrenal masses has been well described. Immunologically compromised patients can obtain significant benefit from these minimally invasive procedures. We describe a case of an enlarging smooth muscle tumor of the adrenal gland in an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) patient and review the sparse literature available on this subject.

Case Report:

A 49-year-old female with AIDS complaining of vague abdominal discomfort was found to have a left adrenal mass. Significant enlargement of the mass was noted during routine follow-up. The patient underwent an elective laparoscopic left adrenalectomy without complications. Pathological review found the mass to be a rare adrenal leiomyoma.

Discussion:

Benign, smooth muscle tumors arising from the adrenal glands are rare. A review of the literature does reveal a propensity for these tumors to occur in the immunocompromised population.

Conclusion:

The ability to manage these tumors laparoscopically is of significant benefit to patients.

Keywords: Incidentaloma, Adrenal mass, Immunocom-promised

INTRODUCTION

Incidental adrenal masses are often discovered during investigative studies for unrelated abdominal/thoracic pathology. Although a number of tumors may arise from the adrenal gland, surgical intervention is always warranted in the setting of functional tumors and in the likelihood of malignancy.1 Many criteria have been established that guide our approach to the adrenal “incidentaloma.” The association between acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), Epstein-bar virus (EBV), and leiomyomas has been described. Leiomyomas of the adrenal gland are very rare except in this population. They are benign in nature and are composed of smooth muscle cells. Very few reports are noted in the literature addressing this rare tumor.2–8 Interestingly enough, most of these tumors have been seen in the immunocompromised population. We report the successful laparoscopic excision of an enlarging left adrenal leiomyoma in a 49-year-old woman with AIDS.

CASE REPORT

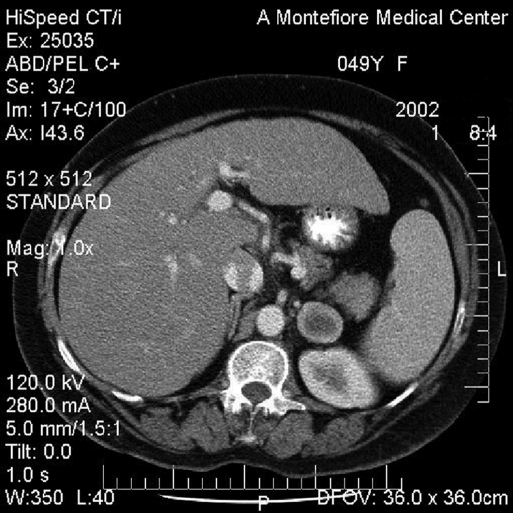

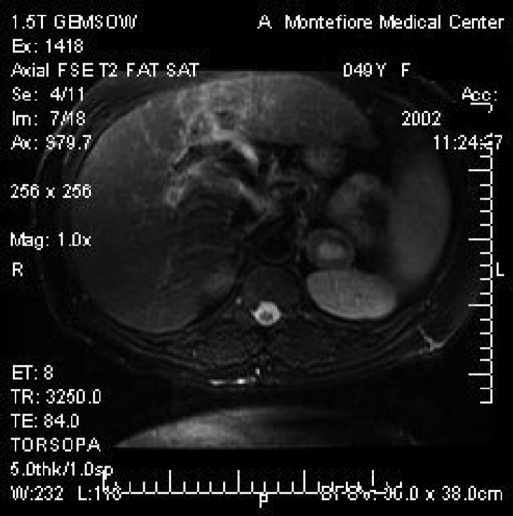

The patient is a 49-year-old female with AIDS who presented to her primary physician in 2001 with the complaint of vague abdominal discomfort. A computed tomographic (CT) scan at the time revealed gallstones and an incidental 1.9x2.1-cm left adrenal mass. Surveillance CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a significant growth in the mass to 4.1x2.7 cm over a 1-year period. The core of the mass had a high signal in the T2 fat suppressed sequence suggestive of central necrosis. No drop occurred in the signal in the in-phase/opposed-phase sequence. (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan of the left adrenal leiomyoma measuring 4.1x2.7 cm (anterior to kidney).

Figure 2.

T2 weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the left adrenal leiomyoma with an enhancing central core.

The standard endocrinological studies were obtained. The patient's 24-hour urine cortisol was within normal limits. Her 24-hour urine catecholamine tests were also normal. A thyroid function test confirmed that she was euthyroid. Plasma dehydroepianndrostenedione (DHEA) was normal. The patient was hypokalemic, but biochemical test results were not consistent with an aldosterone-producing adenoma.

Given the rapid rate of growth over the surveillance period and the patient's underlying medical status, it was recommended that she undergo a laparoscopic left adrenalectomy. With the patient in a lateral transperitoneal position, we explored her laparoscopically and were able to resect the medially located left adrenal mass without complications. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged on the second postoperative day.

Our preoperative differential diagnosis included the possibility of a paraganglioma. As such, the pathological finding of an adrenal leiomyoma was surprising. The specimen consisted of a roughly spherical-shaped, tan-white, well-encapsulated, firm mass. It measured 3.0x3.5x3.0 cm and weighed 17.8 g. A small rim of compressed adrenal cortex was also present. Immunostain for smooth muscle actin was strongly positive. It confirmed the diagnosis and outlined numerous veins at the center of the tumor, consistent with its origin from vascular smooth muscle.

METHOD

Several techniques have been reported for the laparoscopic removal of adrenal tissue.9–11 These include the transabdominal lateral flank approach, posterior retroperitoneal approach, and the anterior abdominal approach. We have a preference for the lateral flank approach and will briefly describe our technique for the left adrenalectomy.

The patient is initially placed in a supine position for the induction of general anaesthesia. Once successfully anesthetized, the patient is turned to the right lateral decubitus position (left side up). The table is flexed to allow for the opening up of the space between the costal margin and the iliac crest. Pressure points are addressed at this time, the patient is secured to the table, and the left arm is secured on an elevated armrest. The patient is then prepped and draped in the usual fashion.

A Veress needle is used to gain access to the peritoneal cavity. It is placed in the anterior axillary line approximately 2 cm below the costal margin. After insufflation to approximately 15 mm Hg, a 5-mm port is placed at the same site. A 5-mm/45-degree scope is placed inside, and the peritoneal cavity is inspected. A 10-mm to 12-mm Optiview trocar is generally placed in the mid left abdomen superior-lateral to the umbilicus. Another 5-mm port is then placed below the costal margin approaching the xiphoid. At times, a 5-mm port is also placed laterally between the costal margin and the iliac crest. This optional port is used primarily for retraction.

The dissection begins with the mobilization of the splenic flexure of the colon, moving the colon inferiorly. The splenorenal ligament is taken down and followed up to the diaphragmatic attachments. This allows the spleen to fall medially with the aid of gravity. Once this is accomplished, it generally creates a valley with the spleen and pancreas towards the left (of the screen) and the kidney and adrenal on the right. The plane between the adrenal and the kidney can generally be identified and the space opened up with an ultrasonic scalpel. The adrenal vein is encountered at the inferior portion of the gland. Medium titanium clips are applied proximally and distally, and the adrenal vein is then transected. Although it is not essential to dissect out the left renal vein, at times this can be helpful in identifying the left adrenal vein. It is essential to follow the vein to the adrenal gland to ensure that it is not an accessory renal vein. Although not always possible, we believe that early identification of the adrenal vein is helpful in maintaining hemostasis throughout the procedure. Once the adrenal vein is transected, the adrenal gland can be retracted superiorly and complete mobilization of the gland accomplished. Of note, no good “handle” for the adrenal gland exists, and it is best to grasp the fatty tissue surrounding the adrenal gland rather than the gland itself as this will lead to tearing of the gland and subsequent bleeding.

Once the gland is mobilized, it is placed in a sterile retrieval bag and removed via the 10-mm port site. This site may need to be enlarged for removal of the gland. Once hemostasis is assured, the ports can be removed under direct vision and the enlarged port site closed.

DISCUSSION

Adrenal incidentalomas are a well-known phenomenon. They are diagnosed in approximately 1% of abdominal CT scans. Autopsy studies have varied with adrenal masses found in up to 9% of patients.12 A surgeon's complete knowledge of the differential diagnosis of adrenal masses is essential. The finding of an adrenal incidentaloma requires concurrent testing to determine the tumor's functional status, as well as its potential for malignancy.1,12 Initial biochemical testing begins routinely with a 24-hour urine collection for catecholamines, metanephrines, and cortisol to exclude a pheochromocytoma or Cushing's syndrome. Patients with hypertension and hypokalemia are evaluated for primary hyperaldosteronism. DHEA is often utilized as an adjunct in differentiating benign from malignant lesions. Current guidelines require the surgical management of tumors found to be hormonally active or suspicious for carcinoma. Although somewhat variable, patients with lesions >4 cm are also candidates for resection.1

Advances in imaging technology have proven to be particularly useful in the evaluation of adrenal masses. CT and MRI are frequently diagnostic in differentiating benign from malignant lesions. The MRI is advantageous in that it does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation; however, it is more expensive. Most adrenal lesions initially appear benign and can be followed with serial imaging studies.1,12

Although leiomyomas of the gastrointestinal tract are quite common, adrenal leiomyomas are rare tumors. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature. Most of these cases have involved patients who are immunosuppressed. The link between the immune system and smooth muscle tumors of the adrenal gland is not clear. It has been postulated that infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) may promote smooth muscle tumors. HIV may have a direct/indirect oncogenic stimulatory effect.1 Previous studies have documented an association between EBV and AIDS-related smooth muscle tumors. The EBV genome has been detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).6 In this patient, investigation for the EBV genome was negative. Although it is well known that patients with AIDS most commonly develop lymphoma or Kaposi sarcoma, we must also be cognizant of the growing association with the rare adrenal leiomyoma.2,7 Hence, the possibility of a smooth muscle tumor should be included in the differential diagnosis in the AIDS population.

CONCLUSION

Given the rare nature of this tumor, we believe this to be the first report of a laparoscopically resected adrenal leiomyoma. In the setting of the immunocompromised population, laparoscopy certainly provides a clinical benefit compared with the benefits of laparotomy.

References:

- 1. Brunt LM, Moley JF. Adrenal Incidentaloma. World J Surg. 2001;25:905–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jacobs IA, Kagan SA. Adrenal leiomyoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1998;69:111–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Parola P, Petit N, Azzedine A, Dhiver C, Gastaut JA. Symptomatic leiomyoma of the adrenal gland in a woman with AIDS. AIDS. 1996;10:340–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goldman RL, Brody PA. Symptomatic leiomyoma of the adrenal. Clin Imaging. 1994;18:277–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Evrad P, Vermyle C, Scheift JM, et al. Leiomyoma of the suprarenal gland in a child with ataxia-telangiectasia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1991;8:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jimenez-Heffernan JA, Hardisson D, Palacios J, et al. Adrenal gland leiomyoma in a child with AIDS. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1995;15:923–929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dahan H, Beges C, Weiss L, et al. Leiomyoma of the adrenal gland in a patient with AIDS. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:259–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Radin DR, Kiyabu M. Multiple smooth muscle tumors of the colon and the adrenal gland in an adult with AIDS. AJNR. 1992; 159:545–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobs JK, Goldstein RE, Geer RJ. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: a new standard of care. Ann Surg. 1997;225:495–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brunt LM. Laparoscopic adrenalectomy. In: Eubanks WS, Swanstrom LL, Soper NJ. eds. Mastery of Endoscopic and Laparoscopic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Williams; 2000;320–329 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gagner M, Lacroix A, Bolte E, Pomp A. Laparoscopic adrdenalectomy: the importance of a flank approach in the lateral decubitus position. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Siren J, Tervahartiala P, Sivula A, Haapiainen R. Natural course of adrenal incidentalomas: seven-year follow-up study. World J Surg. 2000;23:579–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]