Abstract

Background:

The placement of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes is a common procedure in patients with head and neck cancer who require adequate nutrition because of the inability to swallow before or after surgery and adjuvant therapies. A potential complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes is the metastatic spread from the original head and neck tumor to the gastrostomy site.

Methods:

This is a case of a 59-year-old male with a (T4N2M0) Stage IV squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx who underwent percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement at the time of his surgery and shortly thereafter developed metastatic spread to the gastrostomy site. A review of the published literature regarding the subject will be made.

Results:

Twenty-nine cases of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy site metastasis occurring in patients with head and neck cancer have been previously reported in the literature. The pull-through method of gastrostomy tube placement had been used in our patient as well as in the majority of the other cases reviewed in the literature.

Conclusion:

The metastatic spread of head and neck cancer to the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy site is a very rare occurrence. The direct implantation of tumor through instrumentation is the most likely explanation for metastasis; however, hematogenous seeding is also a possibility. To prevent this rare complication, other techniques of tube insertion need to be considered.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

INTRODUCTION

Gauderer et al1 first described the technique of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in 1980. It was originally introduced as an alternative method to conventional open surgical gastrostomy for nutritional support in patients with head and neck cancer. It is considered to be a safer procedure, with a lower complication rate, is less invasive, generally well tolerated, and more cost effective.2 Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy has been shown to improve nutritional status and the quality of life in these patients.3–5

Complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy are relatively uncommon, but include local infection, hemorrhage, dislodgment, peritonitis, bowel perforation, and aspiration pneumonia.6 Another rare complication that appears to be becoming more prevalent is the meta-static implantation of tumor at the PEG tube site. The first case of gastric and abdominal wall metastasis secondary to PEG placement in a patient with head and neck cancer was reported in 1989.7 Since then, 29 similar cases of tumor implantation at the PEG site have been reported. We report another case of tumor implantation at the PEG site from squamous cell cancer (SCC) of the head and neck. A review of the literature helped to determine the possible mechanism of spread.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 59-year-old male with a history of alcoholism and tobacco abuse. In March 2004, he was diagnosed with a (T4N2M0) Stage IV squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the right soft palate, tonsilllar fossa, retromolar trigone, and base of the tongue. He underwent wide resection that included half of the soft palate, the tonsillar region, the retromolar trigone, and about 40% of the base of the tongue. He also underwent a modified neck dissection. To cover the defect, a skin/subcutaneous free flap from the abdomen was utilized. A tracheostomy and PEG tube placement were performed at the time of the original surgery. Postoperatively, the patient had problems with delirium tremens but was able to be discharged on day 7 tolerating tube feedings. All surgical margins were free of tumor involvement. The patient had 2 positive nodes in the right neck, 1 with extracapsular spread, and both lymphovascular and perineural invasion had occurred within the specimen. The patient subsequently underwent 34 treatments of radiation therapy (XRT).

In April 2004, the patient also underwent mandibular odontectomy, alveolectomy, and minor revision of the free flap at the alveolar process. Close to 1 month after insertion of the PEG tube, the patient stated he noticed some granulation tissue forming around the tube site. This progressed rapidly, but the patient neglected to seek medical attention. In July 2004, the patient was referred by his family practitioner with a large 4-cm fungating mass around his tube site. Within 3 weeks, the mass reached a size of 9 cm in diameter (Figure 1). An incisional biopsy was obtained that revealed SCC, and it was felt that this came from the patient's original head and neck cancer. Upper endoscopy was performed that showed the tumor around the bumper or mushroom within the stomach (Figure 2). Further evaluation by computed tomography (CT) showed a large mass extending through the abdominal wall (Figure 3). Metastatic workup to include CT of the head, neck, chest, and abdomen were negative, except for the mass in the abdominal wall and stomach. Radiation-oncology consultation was obtained, and the patient subsequently received 4500 rads, 25 fractions to the abdominal wall. A significant reduction in the size of the mass was obtained. Several weeks later following radiation therapy, the patient had a CT scan that did not show any residual disease. An en bloc resection of the abdominal wall around the PEG to include a wedge re-section of the stomach was performed. Margins were clear, and no residual tumor was detected. The abdominal wall was repaired with Dual Mesh. The patient was discharged 5 days later tolerating a soft puree diet. The patient did well initially; on follow-up, however, exactly 1 year later, from the time of the patient's original head and neck surgery, he developed local recurrence to the jaw. The patient is presently in hospice care.

Figure 1.

Large exophytic lesion around the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube.

Figure 2.

Endoscopically visible tumor around the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube bumper.

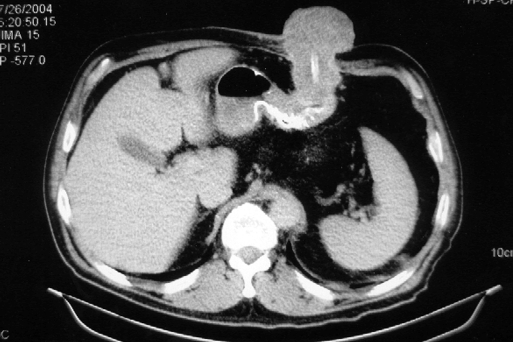

Figure 3.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen revealing transabdominal extent of the tumor.

DISCUSSION

Since its introduction in 1980, PEG has become increasingly popular after surgery, and radiotherapy for improving patient's nutritional status and reducing the duration of the hospital stay.1 It is also the preferred method for feeding patients with severe facial trauma and dysphagia as a result of advanced neurological disease and more recently has been used successfully in patients who require prolonged gastrointestinal decompression.2 Surgical or open gastrostomy has the disadvantage of requiring a laparotomy, and most studies have shown it to be associated with more complications than PEG.8,9

Several methods have been described for the percutaneous endoscopic insertion of the gastrostomy tube, of which the Ponski-Gauderer pull method is the most widely used.1 The pull-through method involves passing the endoscope through the mouth into the stomach. An angiocatheter is introduced through the abdominal wall into the insufflated stomach under direct visualization. A wire is then passed through the angiocatheter, snared endoscopically, and pulled through the patient's mouth. The gastrostomy tube is then attached to the end of the wire and pulled back through the mouth and esophagus into the stomach and out through the abdominal wall. Another less popular technique, known as the “push-through” or “introducer” technique uses the Seldinger method to directly place the tube through the abdominal wall into the stomach that has been insufflated by way of the esophagus.10 This technique does not require passage of the gastrostomy tube over the pharynx.

The reported complication rate for PEG is about 5% compared with about 10% for open gastrostomy, and the reported procedure-related mortality rate is less than 1% compared with about 4% for open gastrostomy.8,9 Complications of PEG include aspiration pneumonia and airway compromise, hemorrhage, tube dislodgement, abdominal wall infection, intraperitoneal leakage and peritonitis, gastroesophageal reflux, dyspnea, transient pneumoperitoneum, tube blockage, pain and infection around the tube site, and formation of granulation tissue.2 A rare but increasingly reported complication in patients with head and neck cancer is the metastatic spread of SCC to the PEG tube site.

The reported incidence of metastatic neoplasms to the stomach have been 0.7% to 2%.11–13 In autopsy findings by Antler et al,14 the incidence of lung cancer metastasizing to the stomach was as high as 9%.

The spread of cancer to a gastrostomy stoma was first reported in 1971 by Alagaratnam,15 who performed the procedure in an open manner. Since 1989, 29 cases have been reported of metastatic seeding from the upper aerodigestive tract to the PEG site. A total of 29 of these patients including our patient had squamous cell carcinoma and 1 had adenocarcinoma (Table 1).2,7,15–39

Table 1.

Cases of Metastasis to Gastrostomy Site

| Reference | Cancer Histology and Stage | Primary Tumor Location | Insertion Method | Metastasis Interval (mos.) | Concurrent Metastasis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1977 Alagaratnam15 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx, Larynx | Open | 24 | None |

| 1989 Preyer7 | SCC, 4 | Nasopharynx | Pull | 3 | Lungs |

| 1991 Bushnell30 | SCC, 4 | Larynx, Lungs | Pull | 15 | Skin |

| 1992 Huang31 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx, Larynx | Pull | 6 | Not reported |

| 1993 Heinbokel16 | Adenoca, 4 | Gastric cardia esophagus | Pull | 2 | Not reported |

| 1993 Laccourreye20 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx | Pull | 11 | Liver |

| 1993 Massoun32 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx | Pull | 4 | Lungs |

| 1993 Meurer29 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx, Larynx | Pull | 12 | Lungs |

| 1993 Meurer29 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx | Pull | 15 | Lungs |

| 1994 Schiano33 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx | Pull | 4 | Not reported |

| 1994 Sharma18 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx | Pull | 6 | None |

| 1995 Becker34 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx | Pull | 3 | Lungs |

| 1995 Becker34 | SCC, 3 | Cervical Esophagus | Pull | 5 | Local relapse |

| 1995 Lee27 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx | Pull | 13 | Gastric ligaments |

| 1998 Van-Erpecum21 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx | Pull | 2–10 | None |

| 1995 Wilson35 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx | Pull | Not reported | Not reported |

| 1997 Schneider22 | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx | Pull | 10 | None |

| 1997 Thorburn23 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx, Larynx | Pull | 11 | Not reported |

| 1998 Potochny19 | SCC, 4 | Hypopharynx | Pull | 9 | None |

| 1999 Deinzer36 | SCC, 3 | Proximal Esophagus | Pull | 3 | Not reported |

| 1999 Hosseini37 | SCC, 2/3 | Distal Esophagus | Pull | 2 | None |

| 2000 Brownl7 | SCC, 3 | Mid Esophagus | Pull | 9 | Lungs, spine |

| 2000 Peghini38 | SCC, 4 | Tongue | Pull | 9 | Skin, Colon, Bone |

| 2000 Douglas25 | SCC, 4 | Tonsillar Fossa | Pull | 3.6 | None |

| 1996 Lauvin39 | SCC, 4 | Esophagus | Pull | 4 | Not reported |

| 2001 Sinclair28 | SCC, 3 | Tongue | Pull | 5 | Axillary Nodes |

| 2001 Cossentino26 | SCC, 4 | Tongue | Pull | 8 | Lung |

| 2001 Cossentino26 | SCC, 2 | Tongue | Pull | 9 | None |

| 2002 Anath2 | SCC, 4 | Floor of mouth | Pull | 3 | None |

| 2003 Thakore24 | SCC, 4 | Larynx | Pull | Unable to determine | Lungs, Bone, Skin, Brain |

| 2005 Mincheff | SCC, 4 | Oropharynx | Pull | 1 | None |

SCC = small cell carcinoma.

It appears that the pull method was used in all these cases. In our case, the patient described tumor developing around the PEG tube 1 month after insertion, but the mean time to PEG site implantation in previously reported cases was 8 months (range, 2 to 17). It is also interesting to note that almost all cases involved advanced (Stage III, IV) SCC of the head and neck region. The exception to that is an adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus.16

Various theories exist concerning the mechanism of spread of the tumor to the PEG site, which include the direct implantation at the time of PEG placement, hematogenous or lymphatic spread, and the possibility of shedding of tumor cells into the gastrointestinal tract from the original head and neck cancer. No controlled experiments have been done to determine whether a particular PEG technique or simply the trauma secondary to the gastrostomy is responsible.24

One hypothesis is that the pull method that was used in all reportable cases may implant or seed malignant cells along the path where instruments have injured the tissue.

Tumor cells from the oropharynx coat and contaminate the bumper of the PEG tube as it is pulled through. This theory is also supported by cases reported by Sharma et al18 and Potochny et al,19 as well as others (Table 1).20–23,27

In an effort to clarify the mechanism of spread, Douglas et al used a tumor kinetic model and concluded that direct implantation of cells is more likely than hematogenous spread in patients whose metastasis appears within 12 months of PEG placement.25,26 In a review of cases since 1989, it was noted that a substantial proportion of patients had PEG metastasis develop at a very short interval after the procedure, as early as 2 months.25 Our patient noticed the tumor within 1 month but failed to seek medical attention.

A study by Kodama et al40 reported that surgical stress might cause an increase in tumor metastasis because high levels of serum cortisol after a surgical procedure may induce morphological changes, both in the capillary lumen and on the tumor cell surface, that may facilitate retention of tumor cells. These results are consistent with the possibility that direct implantation causes tumor metastasis.28

Another theory is that metastasis at the gastrostomy stomata is related to either hematogenous or lymphatic spread of tumor cells.17,26,29,41,42 This hypothesis is in agreement with accepted ideas regarding the mechanism of cancer metastasis.43 In the majority of cases, the primary tumor had known lymph node invasion (before gastrostomy tube placement), and in over half the cases, distant metastases were discovered previously or concurrently with the stomal metastasis.17 This implies that tumor cells were circulating in the lymphatic channels and blood stream.

CONCLUSION

The exact mechanism of gastric and abdominal wall metastasis in patients with PEG placement still remains unclear and controversial. Since 1989, almost every year a case of metastatic implantation at the PEG tube site for head and neck cancer has been reported. PEG placement by the pull method appears to remain the preferred or standard procedure for patients with head and neck cancer in spite of the overwhelming evidence not to use this method. Special precautions must be taken during the procedure to minimize the disruption of tumor cells. It is our suggestion that an alternative to the pull method should be considered in this select group of patients.

Acknowledgments

I would like to especially thank Dr. Rhett Spencer, Department of Radio Oncology, McCleod Regional Medical Center, for his advice and assistance in the treatment of this patient. I would also like to express my sincere thanks and appreciation to my partner, Dr. Brooks Bannister, for his assistance during the surgical portion of the patient's care.

References:

- 1. Gauderer MWL, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ. Gastrostomy without laparatomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:872–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anath S, Amin M. Implantation of oral squamous cell carcinoma at the site of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 2002;40:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gibson SE, Wenig BL, Watkins JL. Complications of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in head and neck patients. Ann Otol Rhinol. 1992;101:46–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gietkau R, Iro H, Sailer D, et al. Percutaneous endoscopically guided gastrostomy in patients with head and neck cancer. Recent Res Cancer Res. 1991;121:269–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibson S, Wenig BL. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in the management of head and neck carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:977–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Safidi BY, Marks JM, Ponsky JL. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:551–568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Preyer S. Gastric metastasis of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy– report of a case [letter]. Endoscopy. 1989; 21:295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wasiljew BK, Ujiki GTM, Veak HN. Feeding gastrostomy: complications and mortality. Am J Surg. 1982;143:194–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rabeneck L, Wray NP, Petersen NJ. Long term outcomes of patients receiving percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tubes. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Russel TR, Brotman M, Norris F. Percutaneous gastrostomy: a new simple cost-effective technique. Am J Surg. 1984;148:132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Washinton K, McDonagh D. Secondary tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: surgical pathological findings and comparison with autopsy survey. Mod Pathol. 1995;8:427–433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whalen GF, Huizinga WKJ, Marszalek A. Perforation of gastric squamous carcinoma metachronous to laryngeal carcinoma: metastatic in origin? Gut. 1998;29:534–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Green L. Hematogenous metastases to the stomach. Cancer. 1990;65:1596–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antler AS, Ough Y, Pichumoni CS, et al. Gastrointestinal metastases from malignant tumors of the lung. Cancer. 1982;49:170–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alagaratnam TT, Ong GB. Wound implantation—a surgical hazard. Br J Surg. 1977;64:872–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heinbokel N, Konig V, Nowak A, et al. A rare complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Metastasis of adeno-carcinoma of the stomach in the area of the gastric stoma [in German]. Z Gastroenterol. 1993;31:612–613 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown MC. Cancer metastasis at percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy stomata is related to the hematogenous or lymphatic spread of circulating tumor cell. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3288–3291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scharma P, Berry SM, Wilson K, et al. Metastatic implantation of an oral squamous cell carcinoma at a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy site. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:1232–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Potochny JD, Sataloff DM, Spiegel JR, et al. Head and neck cancer implantation at the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy exit site: a case report and a review. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12:1361–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laccourreye O, Charbardes E, Merite-Drancy A, et al. Implantation metastasis following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1993;107:946–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Van-Erpecum KJ, Akkersdijk WL, Warlam-Rodenhuis CC, et al. Metastasis of hypopharyngeal carcinoma into the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tract after placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy catheter. Endoscopy. 1995;27:124–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schneider AM, Loggie BW. Metastastic head and neck cancer to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy exit site: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1997;63:481–486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thorburn D, Karim AN, Soutar DS, et al. Tumour seeding following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement in head and neck cancer. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:430–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thakore JN, Mustafa M, Suryaprasad S, Arawal S. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy associated gastric metastasis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;37:307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Douglas JG, Koh W-J, Laramore GE. Metstasis to a percutaneous gastrostomy site from head and neck cancer: radiobio-logic considerations. Head Neck. 2000;22:826–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cossentino M, et al. Cancer metastasis to a percutaneous gastrostomy site [letter]. Head Neck. 2001;23:1080–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lee JH, Machtay M, Unger LD, et al. Prophylactic gastrostomy tubes in patients undergoing intensive irradiation for cancer of the head and neck. Arch Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 1998;124:871–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sinclair JJ, Scolapio JS, Stark ME, et al. Metastasis of head and neck carcinoma to the site of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy: case report and literature review. Am Soc Paren Enteral Nutr. 2001;25:282–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Meurer MF, Kenady DE. Metastatic head and neck carcinoma in a percutaneous gastrostomy site. Head Neck. 1993;15:70–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bushnell L, White TW, Hunter JG. Metastatic implantation of laryngeal carcinoma at a PEG exit site. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:480–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang DT, Thomas G, Wilson WR. Stomal seeding by percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:658–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Massoun H, Gerlach U, Mangegold BC. Puncture metastasis after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [in German]. Chirurg. 1993;64:71–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schiano TD, Pfister D, Harrison L, et al. Neoplastic seeding as a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [letter]. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:131–133 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Becker G, Hess CF, Grund KE, et al. Abdominal wall metastasis following percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Support Care Cancer. 1995;3:313–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wilson WR, Hariri SM. Experience with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy on an otolaryngology service. Ear Nose Throat J. 1995;74:780–762 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Deinzer M, Menges M, Walter K, et al. Metastatic implantation of esophageal carcinoma at the exit site of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [in German]. Z Gastroenterol. 1999;37:789–793 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hosseini M, Gee JG. Metastatic esophageal cancer leading to gastric perforation after repeat PEG placement. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2556–2558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peghini PL, Guaouguaou N, Salcedo JA, et al. Implantation metastasis after PEG: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:480–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lauvin R, Hignard R, Picot D, et al. Tumor graft on the tract of the catheter of percutaneous gastrostomy inserted by endoscopic approach in a patient treated for inoperable cancer of the esophagus [in French]. Presse Med. 1996;25:556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kodama M, Kodama T, Nishi Y, et al. Does surgical stress cause tumor metastasis? Anticancer Res. 1992;12:1603–1616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Strodel WE, Kenady DE, Zweng TN. Avoiding stoma seeding in head and neck cancer patients [letter]. Surg Endosc. 1995;9:1142–1143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Saito T, Iizuka T, Kato H, et al. Esophageal carcinoma metastatic to the stomach: a clinicopathologic study of 35 cases. Cancer. 1985;56:2235–2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fidler IJ. Molecular biology of cancer: invasion and metastasis. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenburg SA. eds. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997;135–152 [Google Scholar]