Abstract

Abdominal cerclages are necessary when the standard transvaginal cerclages fail or anatomical abnormalities preclude the vaginal placement. The disadvantage of the transabdominal approach is that it requires at least 2 laparotomies with significant morbidity and hospital stays. We discuss a case of abdominal cerclage performed laparoscopically. We feel it offers less morbidity and in the proper hands eliminates or significantly shortens hospital stays.

Keywords: Cerclage, Abdominal, Laparoscopy

INTRODUCTION

The original abdominal cerclage was described by Benson and Durfee1 in 1965. The majority of patients diagnosed with incompetent cervix can be treated successfully with a transvaginal cerclage. A select group of patients who have failed the vaginal approach, or have extremely short cervices, anatomically deformed cervix, deeply lacerated cervices, or severely scarred from previous failed vaginal cerclages may benefit from the transabdominal approach.

The disadvantage of the transabdominal approach is the necessity for 2 laparotomies. We describe a successful laparoscopic placement and subsequent successful outcome.

CASE REPORT

The patient is a 36-year-old African-American woman (gravida 2, para 2, aborta 0, last menstrual period 4/1/03) referred from our Maternal Fetal Medicine division for consideration for laparoscopic cerclage. She had 2 prior pregnancies that were lost despite McDonald cerclages. Both pregnancies were lost in the second trimester. The patient had a previous laparoscopy at age 20 with normal findings.

On physical examination, the cervix was normal in appearance, the vagina was normal, and on bimanual examination the uterus was midposition and normal size, shape and contour with some uterine descensus.

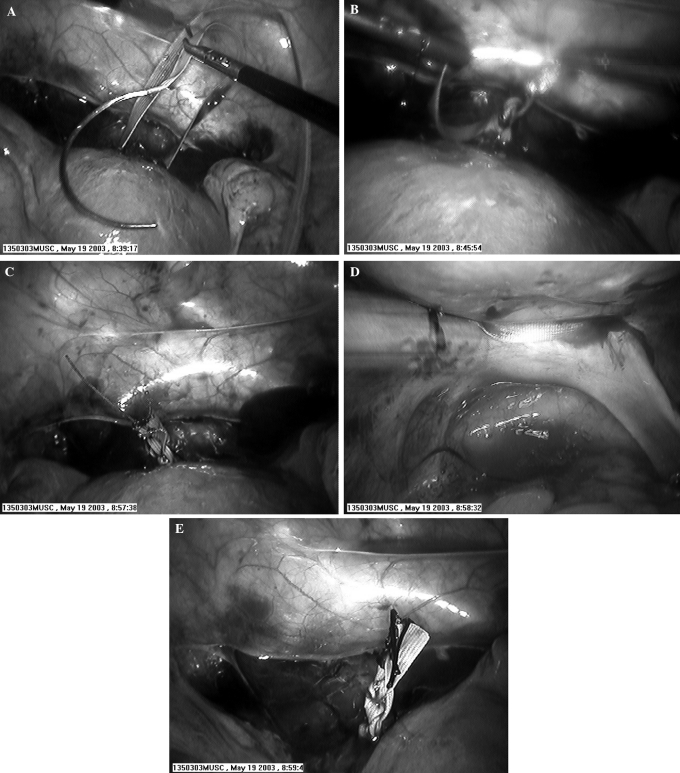

The patient was taken to the operating room after extensive counseling as to possible laparotomy and bleeding and underwent laparoscopic placement of an abdominal cerclage using a 5-mm Mersilene band as is the usual suture used by our Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) division. This included placing the 5-mm Mersilene band around the internal os of the cervix, tying the knots anteriorly, and suturing 2– 0 silk suture to the cut Mersilene to prevent any unraveling (Figure 1). We wanted to perform this procedure exactly as our MFM colleagues would do.

Figure 1.

(A) Placing suture; (B) tying the suture; (C) completed suture: Mersilene and silk; (D) showing posterior placement; (E) end of case after irrigation.

RESULTS

The patient did well postoperatively and was pregnant approximately 3 months later. She had some first trimester bleeding at 8 weeks in which the vaginal ultrasound confirmed cardiac activity. The patient's prenatal course was significant for chronic hypertension, an abnormal glucose tolerance test that was diet controlled with fastings less than 100 and 2-hour postprandials consistently less than 120. She began kick counting at 28 weeks and Non Stress Tests2 were begun at 33 weeks. An elevated creatinine level was noted at 33 weeks and decreasing creatinine clearance was noted, for a diagnosis of preeclampsia. The patient was brought to the Medical University of South Carolina for bedrest and evaluation at 34 weeks. Her 24-hour urine test showed an elevated (1.27 g) protein level. She was offered an amniocentesis at 35 0/7 weeks for lung maturity. She underwent a low transverse Cesarean delivery after lung maturity was confirmed, that day delivering a 5 pound 12 ounce female infant, APGAR 8/9. The patient tolerated the surgery well, and the infant and mother went home on postoperative day 3, doing well. Appropriate instructions and medications were given.

CONCLUSION

Certainly, the usual treatment for women at risk for cervical incompetence is a cerclage placed transvaginally. When this approach has failed, or when this approach is not possible because of anatomic deformities, a transabdominal cerclage is a viable option.

Data clearly show an improved fetal survival rate compared with fetal survival in untreated pregnancies.3–5 The advantage of the abdominal approach is placement of the suture at the internal os with decreased movement. No foreign body enters the vagina. The band can be left in place between pregnancies. The obvious disadvantage is the need for 2 or even 3 laparotomies (although some skillful nonlaparoscopic surgeons have managed to remove these sutures through a colpotomy, most cannot) should the fetus succumb in the second trimester. We advocate the placement of the abdominal cerclage via the laparoscopic approach.

The surgeon should have a skilled assistant and team. The surgeons should have a thorough knowledge of the pelvic anatomy. The ability to adapt to abnormal anatomy and bleeding difficulties cannot be overstated.6,7 One must always keep the patient and fetus' health first, and if unable to succeed laparoscopically, must be prepared to perform the abdominal cerclage via laparotomy to complete the procedure.

References:

- 1. Benson RC, Durfee RB. Transabdominal cervicouterine cerclage during pregnancy for treatment of cervical incompetency. Obstet Gynecol. 1965;25:145–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moore TR, Piacquadio K. A prospective evaluation of fetal movement screening to reduce the incidence of antepartum fetal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160(5 pt 1):1075–1080, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Novy MJ. Transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage: a reappraisal 25 years after its introduction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:1635–1642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cammarano CL, Herron MA, Parer JT. Validity of indications for transabdominal cerclage for cervical incompetence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1871–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Leiman G, Harrison NA, Rubin A. Pregnancy following conization of the cervix. Complications related to cone size. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;136:14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lesser KB, Childers JM, Surwit EA. Transabdominal cerclage: a laparoscopic approach. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:855–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carter JF, Soper DE. Laparoscopy in pregnancy. JSLS. 2004; 8:57–60 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]