Abstract

Primary or idiopathic segmental infarction of the greater omentum is a rare surgical condition. We describe a case of omental torsion in an adult patient who was diagnosed preoperatively by contrast-enhanced computed tomography and managed by laparoscopy.

Keywords: Omentum, Torsion, Computed tomography, Laparoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Torsion of the greater omentum is a rare cause of acute abdomen in adults and children. Its cause is not clear, and it can be classified as secondary only when the cause of torsion is found; otherwise, it is considered of unknown origin (primary). Most patients present with acute right lower quadrant pain, and not surprisingly, they are usually misdiagnosed as having appendicitis.1 Ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) scanning may help to establish the diagnosis and assist in excluding other causes of acute abdomen.2,3 The use of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of acute abdomen is increasingly favored, and in many cases it can be used to treat the problem as well.4,5 We report herein a patient with primary segmental infarction of the greater omentum treated laparoscopically, with emphasis on the CT findings of this rare entity.

CASE REPORT

A 36-year-old man was admitted to the emergency unit with sudden, right, lower quadrant pain. His medical history was unremarkable with no previous abdominal operations. A physical examination revealed a mild fever of 37.8°C and a slightly distended abdomen, with tenderness and discrete guarding in the right hypochondrium. The bowel sounds were normal. The white blood cell count was 7.8x109/L (range, 4 to 10x109/L), and hemoglobin was 13.7 g/dL (range, 10 to 14 g/dL). The biochemical tests were within normal limits, with a lactate dehydrogenase level of 242 U/L (range, 125 to 243 U/L) and C-reactive protein of 54 mg/L (range, 0 to 6 mg/L). Abdominal plain x-ray and urine analysis showed no abnormality. Ultrasonography showed a hyperechoic lesion at the right hypochondrium. Because the physical examination, laboratory results, and abdominal ultrasound findings did not support the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, a CT scan was performed. Contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen revealed streaking of the greater omentum, extending laterally to the umbilicus with a local mass of fat density (Figure 1). Based on these data, omental torsion was suspected and a laparoscopic approach was planned. Following pneumoperiteneum, the 0° laparoscope was inserted through the 10-mm umbilical port. During exploration, a 6x5-cm solid necrotic portion of the right greater omentum was found adhered to the right side of the abdominal wall (Figure 2). About 100 mL of free serosanguinous fluid was found in the right paracolic gutter. No additional abdominal pathology was found. We inserted another 10-mm port into the upper midline and an additional 5-mm port into the right lower quadrant. Blunt and sharp dissection was accomplished with the ultrasonic dissection device (Ultracision, Ethicon, Summerville, NJ, USA), and the necrotic segment of the omentum was resected. Then, this resected part was placed into a bag (Endobag, Specimen Retrieval System, 25040, Auto Suture, USA). The operating time was 28 minutes. Histologically, the omentum showed extensive fat necrosis, acute inflammation, fibrosis, and exuberant mesothelial hyper-plasia. The patient followed an uneventful recovery, and he was discharged home on the first postoperative day.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomographic scan of the abdomen revealed streaking of the greater omentum with a local mass of fat density in a whirling pattern (arrow).

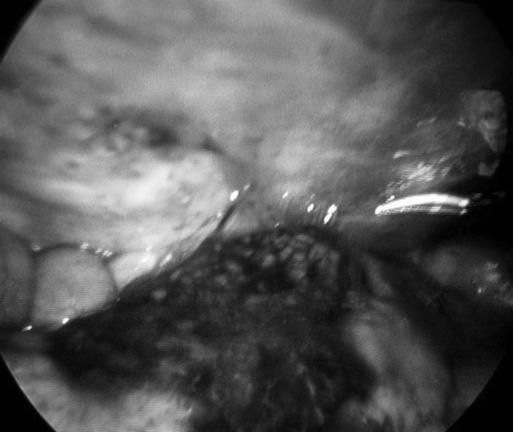

Figure 2.

At exploration, a 6x5-cm solid necrotic segment of greater omentum was found densely adhered to the right side of the abdominal wall.

DISCUSSION

Torsion of the greater omentum is a condition in which the omentum twists along its long axis with subsequent vascular impairment.1 The first reference to omental torsion in the literature is ascribed to Eitel in 1899.6 Secondary torsion is more common, occurring in association with intraabdominal pathologies, such as an internal or external hernia sac, a tumor, a focus of inflammation or adhesions.7 Primary omental torsion is much less common, and predisposing factors include anatomical malformations of the omentum, such as bifid omentum or tongue-like omental projections, local variations in omental fat distribution, particularly in obese patients, and constitutive anomalies of the omental blood supply or pedicle formation.8 Because we did not find any anatomic reason for the omental infarction, such as adhesions or hernias in our patient, the condition was considered as primary omental torsion.

No characteristic or specific signs or symptoms of omental torsion exist, whether primary or secondary.1,7 The cardinal feature of omental torsion is abdominal pain of sudden onset and short duration (24 to 48 h), which is constant, nonradiating, and gradually increasing in severity. The location of the pain may vary depending on which side the omental torsion is on, occasionally occurring on a side, or confined to a single quadrant (usually the lower right quadrant).1,7,8 Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, anorexia, and vomiting, are uncommon. Usually a mild fever is present, and white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein may be elevated. Other possible suspected diagnoses, include acute appendicitis, acute cholecystitis, or viscous perforation, and the final diagnosis is made during the surgical procedure in the majority of cases.1,8–10 The appendix and gallbladder are usually found to be normal at the time of surgical exploration, and it should be stressed that careful exploration of the whole abdominal cavity should be performed.

Because the clinical findings are not specific, CT findings of omental torsion should be searched for an accurate diagnosis.2 With segmental torsion of the omentum, the differentiation between primary infarction and infarction caused by torsion is impossible on the basis of radiographic studies.3 Imaging findings may be similar to those of epiploic appendicitis, abdominal pannuculitis, and focal necrosis due to pancreatitis. A helpful distinguishing sign for epiploic appendicitis is its location anterior or anterolateral to the ascending, descending, or sigmoid colon, while omental lesions are usually located medial to the ascending or descending colon. The key to the diagnosis of omental torsion is the presence of a characteristic concentric linear strand. This important radiological sign is not present in other omental diseases.2,3 With the characteristic CT findings of our patient, the preoperative diagnosis was consistent with the final operative picture.

Diagnosis can be made and resection performed using laparoscopic techniques.9 The advantages of the use of laparoscopy include complete examination of the abdominal cavity to confirm the diagnosis, aspiration and washing of the peritoneum, and decreased postoperative pain and wound-related complications.10,11 In the present case, therapeutic laparoscopy was also achieved. Resection of the necrotic omentum with the ultrasonic dissection device was performed successfully. Nonoperative management can be preferred in patients who are hemodynamically stable and have radiological signs of torsion of the omentum in the preoperative period, unless acute abdomen exists.

CONCLUSION

Surgeons and radiologists should be familiar with the symptoms and specific CT findings of omental torsion for establishing a correct preoperative diagnosis. The laparoscopic approach allows careful and thorough exploration of the abdominal cavity with the possibility of surgical intervention, especially for patients with unclear symptoms and nonspecific abdominal pain. Operative confirmation of omental torsion may be followed by laparoscopic resection of the affected segment as the definitive therapeutic approach.

References:

- 1. Epstien LI, Lempke RE. Primary idiopathic segmental infarction of omentum: case report and collective review of the literature. Ann Surg. 1968;167:427–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atar E, Herskovitz P, Powsner E, Katz M. Primary greater omental torsion: CT diagnosis in an elderly woman. Isr Med Assoc J. 2004;6:57–58 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aoun N, Haddad-Zebouni S, Slaba S, Noun R, Ghossain M. Left-sided omental torsion: CT appearance. Eur Radiol. 2001;11:96–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sozuer EM, Bedirli A, Ulusal M, Kayhan E, Yilmaz Z. Laparoscopy for diagnosis and treatment of acute abdominal pain. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2000;10:203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Udwadia TE. Diagnostic laparoscopy, a 30-year overview. Surg Endosc. 2004;18;6–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eitel GG. Rare omental torsion. NY Med Rec. 1899;55:715 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Houben CH, Powis M, Wright VM. Segmental infarction of the omentum: a difficult diagnosis. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karayiannakis AJ, Polychronidis A, Chatzigianni E, Simopoulos C. Primary torsion of the greater omentum: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:913–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanchez J, Rosado R, Ramirez D, Medina P, Mezquita S, Gallardo A. Torsion of the greater omentum: treatment by laparoscopy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;12:443–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chung SC, Ng KW, Li AK. Laparoscopic resection for primary omental torsion. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62:400–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gassner PE, Cox MR, Patrick CC. Torsion of the omentum: Diagnosis and resection at laparoscopy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:466–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]