Abstract

Background:

A 70-year-old male approximately 3 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy presented to his primary care physician with a 4-month history of generalized malaise.

Methods:

A workup included magnetic resonance imaging that revealed a perihepatic abscess. The patient underwent ultrasound-guided drainage, with the removal of 1400 mL of purulent fluid and placement of 2 drains. Computed tomographic scanning showed resolution, and he was discharged home on oral antibiotics. At 2-month follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, denying any constitutional symptoms. However, abdominal computed tomographic scanning revealed recurrence of the abscess, which measured approximately 18x9x7.5 cm, with mass effect on the liver. The patient was placed on intravenous antibiotics and scheduled for operative drainage. The abdomen was entered with a right subcostal incision, and 900 mL of purulent fluid was drained. We also noted abscess erosion through the inferolateral aspect of the right diaphragm into the pleural space. The pleural abscess was loculated and isolated from the lung parenchyma. Palpation within the abscess cavity revealed 9 large gallstones. Following copious irrigation and debridement of necrotic tissue, 3 drains were placed and the incision was closed.

Results:

The patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged home on postoperative day number 6. Follow-up imaging at 3 months demonstrated resolution of the collection.

Conclusion:

Spillage of gallstones is a complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, occurring in 6% to 16% of all cases. Retained stones rarely result in a problem, but when complications arise, aggressive surgical intervention is usually necessary.

Keywords: Cholecystectomy, Complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Perihepatic abscess, Retained gallstones

INTRODUCTION

Spillage of gallstones is a frequent complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, occurring in 6% to 16% of all cases. Retained stones rarely represent a problem to the patient, but when complications arise, aggressive surgical intervention is usually necessary. We present the case of an elderly gentleman who presented to our tertiary care center 3.5 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy at a community hospital. He failed nonoperative treatment and required open drainage. Although his recovery course had been uncomplicated, not all patients benefit from easy recuperation. We also summarize some of the treatments for gallstones retained in the thoracic cavity and encourage surgeons to use every tool in their arsenal to remove all gallstones during surgery and to document if all stones were not retrieved.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old morbidly obese male presented to his primary care physician with a 4-month history of generalized aches and pains approximately 3.5 years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a subphrenic abscess. The patient underwent ultrasound-guided abscess drainage, with the removal of 1400 mL of frank pus and placement of 2 drainage catheters in the abscess cavity. He was admitted to the hospital and treated with intravenous antibiotics, with a good clinical response. Unfortunately, the catheters were inadvertently dislodged 4 days after the procedure. A follow-up computed tomographic (CT) scan showed minimal residual abscess. The patient was discharged home on oral antibiotics.

Two months later, the patient returned for routine follow-up, at which time he was completely asymptomatic. He specifically denied fever or chills, and his white blood cell count was normal. Interestingly, an abdominal CT scan revealed recurrence of the abscess, which measured approximately 18x9x7.5 cm, with mass effect on the liver. The patient was placed on intravenous antibiotics and scheduled for intraoperative abscess drainage.

The abdomen was entered via a right subcostal incision. Dense adhesions were present in the right upper quadrant, particularly between the liver and the diaphragm. Upon entry of the perihepatic abscess cavity, 900 mL of purulent material was drained (cultures subsequently positive for Enterococcus). The abscess cavity was found to have eroded through the inferolateral aspect of the right diaphragm into the right pleural space. The pleural abscess cavity was loculated and completely isolated from the lung parenchyma. Palpation within the abscess cavity revealed multiple, large gallstones (Figure 1). A total of 9 gallstones were removed, followed by copious irrigation and debridement of necrotic tissue. A multiple-lumen sump drain and 2 closed-suction drains were placed within the abscess cavity. Because the abscess was completely loculated, tube thoracostomy was not performed.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative photograph of 9 large gallstones removed from the subphrenic/pleural abscess cavity. Arrow points to gallstone.

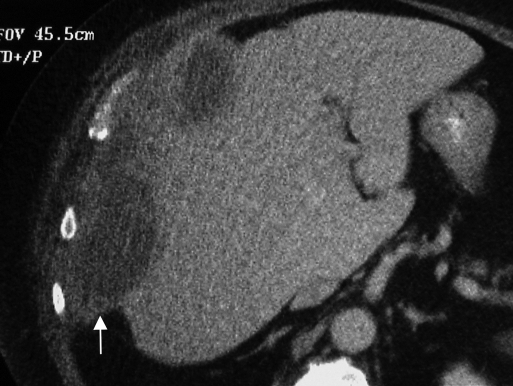

The patient was initially admitted to the intensive care unit and later transferred to the surgery ward on postoperative day 1. The remainder of his hospital course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home on postoperative day 6. Interestingly, review of the preoperative CT scan revealed previously unnoticed gallstones within the abscess cavity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Computed tomographic scan showing a gallstone within the abscess cavity. This finding was not appreciated preoperatively.

DISCUSSION

Since its inception in 1987, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has largely replaced the open approach for treatment of cholecystitis and cholelithiasis. The benefits of laparoscopic surgery are well described and include greatly reduced postoperative hospital stay and surgical pain. Nevertheless, rare but serious complications, such as vascular and common bile duct injuries, occur twice as often with a laparoscopic approach versus an open procedure.1 A more frequent undesired event is accidental spillage of gallstones, occurring in 6% to 16% of the cases in recent large retrospective analyses.2,3 Although the bile is easily irrigated in such cases, removal of gallstones from within the abdominal cavity can prove more challenging.

A retrospective study in 1998 reported 581 cases of spilled gallstones during 10,174 laparoscopic cholecystectomies, an occurrence rate of 5.7%.2 Thirty-four of these cases were converted to an open procedure in an attempt to remove lost gallstones, while of the remaining 547 patients only 8 (0.08%) developed postoperative complications requiring reoperation. Other investigators reported even lower incidences; only 0.1% to 2.5% of all patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy had unretrieved gallstones.4,5 Although some of the retained stones caused intraabdominal complications, more than half eroded through adjacent structures. A review of the literature published in 2002 revealed 127 case reports describing spillage of gallstones since 1963, of which 56 (44%) involved intraperitoneal abscess, 23 (18%) abdominal wall abscess, 15 (12%) thoracic abscess, 13 (10%) retroperitoneal abscess, 4 (3%) pelvic abscess, and 4 (3%) pericolic abscess.6 In addition, an incidence of 3, 4, and 5 (2% to 4%) of bladder fistulization was noted, ie, stones found in hernia sacs and small bowel obstruction, respectively.

Thus, overall thoracic complications of unretrieved gallstones are rare, but do represent significant morbidity in the afflicted patient. Including our case study, we note 18 cases of intrathoracic complications of retained gallstones, such as abscess formation, pleural effusion, empyema, pleurolithiasis, broncholithiasis, and cholelithoptysis. One of these cases occurred following an open cholecystectomy in 1975, while the rest followed laparoscopic excision.7 Of the 18 cases, 4 were managed nonoperatively with one case resolving without intervention,8 one case resolving with CT-guided drainage,9 and the other 2 after flexible bronchoscopy.10,11 All of the remaining 14 cases

required operative treatment. Of those, 2 patients were treated with thoracoscopy,12,13 8 required thoracotomy,7,14–20 and the remaining 4 patients underwent abdominal exploration, either via a right subcostal incision or through a midline laparotomy.21–23

Indeed, serious surgical intervention is frequently required to treat cases of stones spilled during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. What we described above are merely cases of thoracic involvement, which only constitute about 12% of all reoperations for spilled stones.6 And while large studies do show that the frequency of complications resulting from retention of spilled stones is rare, they nevertheless pose a serious threat to the patient and must be addressed during the original surgery. Papasavas et al6 described a series of maneuvers that should facilitate stone collection following spillage. The site of perforation must be controlled, and every effort to minimize spillage must be utilized, including addition of extra ports, use of a large bore suction device, specimen collection bag, 30° laparoscope, and fan liver retractor. Thus, while conversion to laparotomy is probably unnecessary, the surgeon must document the presence of retained gallstones in the operative report to facilitate diagnosis and treatment in case the patient re-presents, particularly to a different hospital.

References:

- 1. Fletcher DR, Hobbs MS, Tan P, et al. Complications of cholecystectomy: risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 1999; 229 (4): 449–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schafer M, Suter C, Klaiber C, Wehrli H, Frei E, Krahenbuhl L. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A relevant problem? A retrospective analysis of 10,174 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc. 1998; 12 (4): 305–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Memon MA, Deeik RK, Maffi TR, Fitzgibbons RJ., Jr The outcome of unretrieved gallstones in the peritoneal cavity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A prospective analysis. Surg Endosc. 1999; 13 (9): 848–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Targarona EM, Balague C, Cifuentes A, Martinez J, Trias M. The spilled stone. A potential danger after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 1995; 9 (7): 768–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sarli L, Pietra N, Costi R, Grattarola M. Gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 1999; 23 (11): 1186–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Papasavas PK, Caushaj PF, Gagne DJ. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2002; 12 (5): 383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwegler N, Endrei E. Gallstone in the lung. Radiology. 1975; 115 (3): 541–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chan SY, Osborne AW, Purkiss SF. Cholelithoptysis: an unusual complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Surg. 1998; 15 (6): 707–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brueggemeyer MT, Saba AK, Thibodeaux LC. Abscess formation following spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 1997; 1 (2): 145–152 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Downie GH, Robbins MK, Souza JJ, Paradowski LJ. Cholelithoptysis. A complication following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chest. 1993; 103 (2): 616–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chopra P, Killorn P, Mehran RJ. Cholelithoptysis and pleural empyema. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999; 68 (1): 254–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brazinsky SA, Colt HG. Thoracoscopic diagnosis of pleurolithiasis after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chest. 1993; 104 (4): 1273–1274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Neumeyer DA, LoCicero J, 3rd, Pinkston P. Complex pleural effusion associated with a subphrenic gallstone phlegmon following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Chest. 1996; 109 (1): 284–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Willekes CL, Widmann WD. Empyema from lost gallstones: a thoracic complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1996; 6 (2): 123–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rice DC, Memon MA, Jamison RL, et al. Long-term consequences of intraoperative spillage of bile and gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 1997; 1 (1): 85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelty CJ, Thorpe JA. Empyema due to spilled stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998; 13 (1): 107–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Preciado A, Matthews BD, Scarborough TK, et al. Transdiaphragmatic abscess: late thoracic complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999; 9 (6): 517–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Noda S, Soybel DI, Sampson BA, DeCamp MM., Jr Broncholithiasis and thoracoabdominal actinomycosis from dropped gallstones. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998; 65 (5): 1465–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Barnard SP, Pallister I, Hendrick DJ, Walter N, Morritt GN. Cholelithoptysis and empyema formation after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995; 60 (4): 1100–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Werber YB, Wright CD. Massive hemoptysis from a lung abscess due to retained gallstones. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001; 72 (1): 278–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lee VS, Paulson EK, Libby E, Flannery JE, Meyers WC. Cholelithoptysis and cholelithorrhea: rare complications of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastroenterology. 1993; 105 (6): 1877–1881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leslie KA, Rankin RN, Duff JH. Lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: are they really benign? Can J Surg. 1994; 37 (3): 240–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thompson J, Pisano E, Warshauer D. Cholelithoptysis: an unusual complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Clin Imaging. 1995; 19 (2): 118–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]