Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Traditional trocar tip design for laparoscopic access incorporates cutting blades to penetrate the body wall. More recently, trocars applying tissue dilation have been used that create a smaller defect, seldom requiring fascial wound closure. Four 12-mm commercially available single-use trocar designs were evaluated for postoperative pain.

Methods:

The 4-trocar types included 2 cutting (single or pyramidal bladed) and 2 dilating trocars (radially or axially dilating) type. Fifty-six patients undergoing transperitoneal laparoscopic renal surgery were randomized and blinded to one of the 4 trocar types. In each case, trocars were placed in a standard “diamond” configuration: three 12-mm study trocars and a lateral 5-mm trocar that served as a reference point for normalizing patients' pain scores. Postoperative pain based on a visual analog scale and complications were assessed.

Results:

No statistically significant difference existed in pain scores between different trocar types or trocar sites at 3-hour, 24-hour, and 1-week postoperative assessment time points. Eight (4.8%) minor complications occurred: bleeding in 7 (4.2%) and 1 (0.6%) wound infection. The radially dilating trocar had more device malfunction (P<0.05) than did the others.

Conclusion:

All 4 disposable trocars, muscle cutting or dilating type, were safe and yielded similar postoperative pain scores with or without the fascial wound closure after renal laparoscopy.

Keywords: Trocar, Laparoscopy, Pain

INTRODUCTION

Gaining safe access to the body cavity is a critical first step for a successful laparoscopic surgery. Traditional trocar tip designs use retractable sharp bladed tips (pyramidal or single blade) to penetrate the body wall by cutting through the fascia and muscle layers. More recently, conical trocar tip design for tissue dilation (radially or axially) to achieve access has been introduced. In the gynecological and general surgical literature, the radially dilating trocar has been shown to be associated with less wound pain than that produced by the bladed trocar.1,2 The dilating trocars have been shown in animal studies to create a smaller abdominal wall wound compared with the bladed trocar wounds.3,4 Also, some authors have reported that it is not necessary to close the fascial wound created by a dilated trocar.5 The trocar tip design and fascial wound closure may be some of the factors associated with trocar-site pain and the risk of complications including the development of a trocar-site hernia. We performed a prospective study in patients undergoing urologic laparoscopy, specifically transperitoneal laparoscopic renal surgery, to compare 4 currently available disposable trocars with different tip varieties for postoperative pain and complications in a randomized double-blind (ie, patient and postoperative evaluator) setting.

METHODS

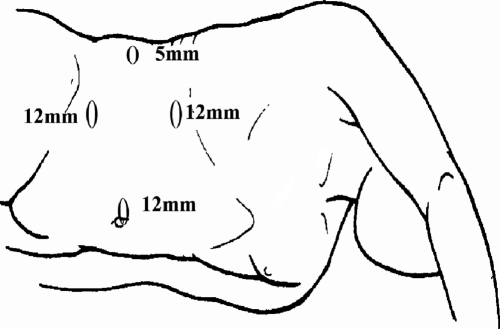

Our medical school Human Studies Committee approved the study protocol. Patients' ≥18 years old undergoing laparoscopic transperitoneal renal procedures were invited to participate in the study. Fifty-six patients were prospectively randomized and blinded to receive one of the 4 types of 12-mm study trocars. All the trocars were inserted after pneumoperitoneum was established with a Veress needle. The procedures performed included radical or total nephrectomy,36 nephron-sparing surgery,9 pyeloplasty,8 and renal cyst decortication.3 A standardized lateral 5-mm, noncutting, metal trocar (Storz EndoTIP, Storz Inc., Tuttlingen, Germany) was placed in each case and used as a standard reference point to normalize the patients' pain scores with other trocar sites. Evaluation of pain is challenging due to its intrinsically subjective nature and pain threshold variation from person to person. Additionally, there could be variation of pain at different anatomic sites. As such, the study was designed to assess trocar-site pain for only the flank approach with a standardized “diamond” configuration for the placement of trocars (Figure 1). Normalization of pain scores was performed by calculating the mean pain score for the lumbar trocar site and normalizing it to the 5-mm lateral port pain score for each individual patient according to his pain assessment score along the visual analog pain scale (VAS). The pain scores at the other trocar sites were correspondingly normalized to the 5-mm lateral port site, to eliminate the individual differences in the pain threshold among the participants.

Figure 1.

“Diamond” trocar configuration.

Based on the pain scores from previously published research protocols, we expect pain scores (VAS) with radially dilating trocars, single-bladed trocars, and pyramidalbladed trocars to be 3.5, 6.2, and 6.2, respectively. With an SD of 2.5 and to achieve a power of 81%, the study required 14 patients in each arm to detect differences with a significance of P=0.05. As such, 56 patients were incorporated into the study. The pain score analysis was carried out with the paired t test using ANOVA data analysis for variable parameters.

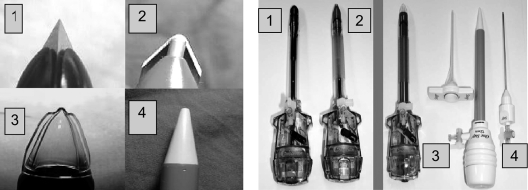

Devices

The cutting trocars included a PB (Ethicon Inc., Cincinnati, OH) and SB trocar (Ethicon Inc., Cincinnati, OH). The dilating trocars evaluated were an AD (Ethicon Inc., Cincinnati, OH) and an RD Step-system (US Surgicals Inc., CA) (Figure 2). The RD trocar system consisted of a 1.9-mm Veress needle surrounded by an expanding mesh polymeric sleeve. After establishing the pneumoperitoneum, the mesh sleeve was supported with one hand while the blunt-tipped RD trocar was radially dilated into the sleeve in the abdominal wall up to 12 mm with the other hand. The PB, SB, and AD trocars were deployed in a standard fashion. The fascial closure was performed for SB and PB trocar sites by using a Carter-Thomason closure device. RD and AD trocar sites were not routinely closed unless frequent dislodgment of the trocar occurred. The skin incision was closed by using subcuticular Vicryl.

Figure 2.

Trocar tips (left) and trocar types (right)1: pyramidal bladed2; single bladed3; axially dilating4; radially dilating.

All complications, such as abdominal wall vessel bleeding, intraabdominal vascular or visceral injuries, related to the trocar deployment were documented. Trocar-related events during the operative procedure, such as gas leakage, trocar dislodgment, problems in handling the reducer mechanism and failure of trocar seal integrity, were documented. The morcellation site, specimen extraction, and hand-assist device site location when used were documented. A physician who did not perform or assist the operation assessed the trocar sites for pain, bleeding, and ecchymoses at 3 and 24 hours postoperatively. The pain at each trocar site was assessed by using a VAS from 1–10, with 1 being no pain and 10 being maximum pain. The trocar-site bleeding was estimated by measuring the area of bloodstain in millimeters on the dressing or the size of ecchymosis at the trocar site. Follow-up evaluations were performed at 1week and 3 months for pain and trocar-site hernia. Physical examination specifically evaluating for the presence of trocar-site hernia was carried out during the office visit by the attending physician or by a telephone interview at 6, 12, and 18 months.

RESULTS

A total of 221 trocar insertions were performed in 56 patients. Additionally, 12 hand-assist devices were deployed during some of the procedures. There were 165 trocar sites for evaluation in the study including 43 PB, 41 SB, 38 AD, and 43 RD trocar sites. The mean patient body mass index was 31.3 (range, 20 to 62) and was similar among all 4 trocar study groups. The mean patient age was 58 years (range, 19 to 90) and included 30 males and 26 females. The mean operative time was 263 minutes (range, 75 to 525) with an average estimated blood loss of 234mL (range, 10 to 3500). The lower abdominal quadrant was used for primary port insertion in 37 (66%) cases.

The mean pain scores at 3 hours, 24 hours, and 1-week postoperatively were not statistically significant among different trocar varieties (Table 1) at 24-hour evaluation. The mean pain scores at 12-mm “pure” trocar sites not used for morcellation or specimen extraction were statistically significantly lower than the pain scores at morcellation, hand-assist device, or specimen extraction sites (P<0.05, adjusting for multiple comparisons) at 3-hour, 24-hour, and 1-week postoperative evaluations (Table 1). Also, the morcellation sites had significantly lower mean pain scores than did the hand-assist device sites (P<0.05, after adjusting for multiple comparisons), at 3-, 24-hour, and 1-week postoperative evaluations. Also at 1- and 3-month postoperative evaluations, no statistically significant differences were noted in the mean pain scores between “pure” trocar, morcellation, and hand-assist device sites. Closure of the fascial layer was not routinely performed with the RD or AD trocars on 82% of occasions. The fascial layer of the dilating trocar sites was closed on 6 occasions (7%) for frequent trocar slippage, and all the bladed trocar sites were closed. There was no statistically significant difference in the mean pain scores between the fascially closed90 and unclosed sites75 at 3-hour (VAS 3.8 and 3.4, P=0.13), 24-hour (VAS 4.1 and 3.9, P=0.9) and 1-week (VAS 2.9 and 2.8, P=0.7) postoperative time points, respectively. Anatomically, in our series, the umbilical and upper and lower quadrant trocar sites caused a similar degree of pain; however, the 5-mm lateral trocar site caused significantly less pain (P<0.05) than did the other sites.

Table 1.

Pain Analog Scores at 3 Hours, 24 Hours, and 1 Week With Regard to 4 Trocar Types, Morcellation Sites, and Hand-Assist Device Sites

| n | 3 Hrs | P Value <0.05*† | 24 hrs | P Value <0.05*† | 1 Week | P Value <0.05*† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 38 | 2.8 | HA, MS | 3.4 | HA, MS | 2.1 | HA, MS |

| RD | 43 | 3.4 | HA, MS | 4.8 | HA, MS | 2.1 | HA, MS |

| SB | 41 | 3.1 | HA, MS | 4.2 | HA, MS | 2.4 | HA, MS |

| PB | 43 | 3.5 | HA, MS | 4.0 | HA, MS | 2.4 | HA, MS |

| Morcellation Site | 16 | 5.1 | HA | 6.3 | HA | 3.4 | HA |

| Hand-Assist Site | 12 | 5.6 | none | 8.5 | none | 4.7 | none |

P<.05 means that the tested trocar resulted in less pain than the listed trocars. No significant differences existed in the pain scores between the 4 trocar types.

HA=Hand-assist site; MS=Morcellation site.

No injuries occurred to intraabdominal vessels or bowel caused by any of the trocar types. A superficial liver injury occurred due to a Veress needle insertion with the sleeve of an RD trocar during primary access. The bleeding was controlled by compression with Gelfoam on the bleeding site for a few minutes. The postoperative bleeding or bruising at the port site by different study trocars was not significantly different. Eight (4.8%) minor complications occurred: bleeding from the trocar site in 7 (4.2%) and wound infection in 1 (0.6%). Bleeding resulted from primary trocar access in only a single case; the remaining bleeding episodes occurred from secondary access sites. Four bleeding episodes resulted from PB trocars, and the remaining 3 resulted from one of each of the other 3 trocar varieties. No epigastric vessel injury occurred. Bleeding was controlled by full-thickness abdominal wall suturing using a Carter-Thomason device in one case caused by a PB trocar. In 2 cases, fascial suturing using a Carter-Thomason device was used to control bleeding caused by a PB trocar. A single bleeding episode each caused by PB, SB, RD, and AD trocars at the peritoneal surface was controlled by bipolar electrocautery. A solitary wound infection occurred at the umbilical PB trocar site in a patient who had previous splenectomy. Staphylococcus aureus was grown from the wound, which was treated with cephalexin.

Thirty (14 AD and 16 RD) dilating trocars were inserted at the 12-mm midline umbilical site. Fascial closure was not performed at 21 umbilical sites created by the dilating trocars (10 AD and 11 RD sites). Gas leakage events8 and trocar “slippage”12 occurred more often with the RD trocar compared with the other 3 trocars combined (12 and 10, respectively) (P<0.05) (Table 2). Device malfunction episodes with the RD trocar were more frequent than with the other trocars combined (P<0.05) (Table 2). This was mainly due to the problems with the handling of the reducer mechanism, and dislodgment of the trocar during removal of the EndoGIA stapler. However, device malfunction did not directly contribute to any of the trocar-related complications. There were no trocar-site hernias during a minimum follow-up of 18 months (range, 14 to 36).

Table 2.

Device Malfunction and Trocar-Related Complications

| Device Malfunction | RD | AD | PB | SB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reducer mechanism problems | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trocar tip blunt (too hard to push) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Sheath torn | 3 | NA | NA | NA |

| Gas leak events (valve membrane disruption) | 8 (0) | 3 (1) | 4 (2) | 5 (1) |

| Trocar “slippage” | 12 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Total | 37 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| Trocar-Related Complications | ||||

| Trocar-site bleeding | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Wound infection | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Visceral injury (superficial liver injury) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have suggested that RD trocar sites are less painful compared with bladed trocar insertion sites.1,2,5 However, in our randomized study, no statistically significant difference occurred in the trocar-site pain between different 12-mm trocars, whether the trocar tip was bladed or the dilating type (P>0.05). In this regard, it is of note that our study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to directly compare axial, radial, and cutting trocars in a prospective manner. Interestingly, and possibly further validating our findings, is the observation that pain at the morcellation, specimen extraction, and hand-port sites was statistically significantly higher than pain at the 12-mm pure trocar sites not used for morcellation or specimen extraction. Also, of note, the morcellation sites were less painful than the hand-assist device sites in the early postoperative period (P<0.05).

The fascial layer of the dilating trocar sites was closed on 6 occasions (7%) for frequent trocar slippage. Interestingly, contrary to our hypothesis, fascial closure compared with unclosed sites was not associated with increased discomfort. Pain is a subjective complex symptom, and no significant difference in pain between different types of trocars in our study contrary to findings in other studies could be partly due to the nature of the procedure and location of trocar sites. Renal laparoscopy is a complex procedure that on many occasions requires an incision or insertion of a hand-assist device to extract the specimen. The incision pain from specimen extraction site, morcellation, or hand-assist device site may “alter” or “mask” the pain at the trocar sites. Also, postoperative abdominal discomfort or distension may alter the trocar-site pain. Nevertheless, in our randomized study, only patients undergoing renal laparoscopy were selected, and trocar site configuration was standardized. Also, the individual trocar-site pain was “normalized” to a standard lateral 5-mm nondisposable trocar site.

Studies have shown trocar-related access injuries can account for up to half of the reported laparoscopic complications.6–17 Turner6 reviewed the results on the safety of RD trocars (the Step system) from 11 studies. There were 15 000 RD trocar insertions with no major vascular injuries and no deaths reported. In our randomized study, all 4 disposable trocar types were found to be safe with no major complications. Eight minor complications occurred, which included 7 bleeding sites from the abdominal wall that were easily controlled by standard surgical techniques with no significant blood loss. Sharp and coworkers10 searched MEDLINE and FDA Medical Device Reporting databases for reports of complications associated with optical access trocars not reported in the medical literature. Seventy-nine serious injuries were cited during general surgical and gynecological procedures; 26 were due to Optiview nonbladed and 53 to Visiport bladed trocars. With the nonbladed trocar, 6 major vessel injuries and 12 bowel perforations occurred with one associated mortality. With the bladed system, 31 major vessel injuries and 6 bowel injuries occurred, with 3 associated deaths. Thomas and coauthors11 reported on their use of optical access trocars with a recessed blade at its distal tip in 1283 urologic procedures. They reported 4 (0.31%) injuries including 1 small-bowel injury, 1 mesenteric injury, and 2 epigastric vessel injuries. Nonetheless, in our opinion, the AD trocar access (ie, Optiview, Ethicon Inc.) is superior due to several features. First, it is safe and its shaft is constructed such that it securely remains in position once placed across the abdominal wall. Second, fascial closure is not required thereby reducing the operative time and cost. Lastly, the Optiview transparent trocar sheath allows the withdrawal of the trocar through the abdominal wall without completely dislodging the trocar. Studies have also reported that the application of optical trocar systems can reduce the complications related to primary trocar insertion.13,17

The incidence of abdominal wall hernias with metal bladed trocars, despite fascial closure, is approximately 1% (range, 0.02% to 5%).3,4,18 Bhoyrul and coworkers15 demonstrated in a porcine model that the defect in the abdominal wall caused by the RD system was 52% smaller in width than the defect caused by the cutting trocar. In keeping with the laboratory findings, clinical studies with RD trocars have shown no hernias, despite no fascial closure of these sites.17,18 However, more recently Nakada and coworkers18 reported a case of hernia through a nonmidline site created by a nonbladed 12-mm trocar where fascial closure was not performed. Shalhav and coworkers19 assessed the safety of fascial nonclosure at the nonmidline 12-mm AD trocar sites in patients undergoing renal surgery. With a mean follow-up of 4.8 months, there were no hernias in all 20 patients with fascial nonclosure compared with 20 matched patients who had fascial closure.19 However, these studies, as with ours, may underestimate the incidence of trocar-site hernias because the evaluations were frequently performed by telephone interview. Of note, even though the midline trocar-site fascial layer (without muscle cover) was not routinely closed, no symptomatic hernia has occurred among 30 dilating trocars placed in this location in our study.

CONCLUSION

All 4 disposable trocar varieties were safe and yielded similar postoperative pain scores with or without the trocar-site fascial wound closure. Dilating access devices do not need fascial closure, and thereby can save operative time. Device malfunction due to reducer mechanism problems and trocar dislodgment was more often seen with RD trocars. The 12-mm trocar sites resulted in statistically significant less postoperative pain than the hand-assist device or morcellation wound sites in the early postoperative period. With a minimum follow-up of 1.5 years, no symptomatic hernias have been related to these trocars. Based on these findings, the AD trocars have become our trocar of choice.

Contributor Information

Ramakrishna Venkatesh, Washington University School of Medicine, Division of Urology, St. Louis, Missouri, USA..

Chandru P. Sundaram, Indiana University Medical Center, Department of Urology, Indianapolis, USA..

Robert S. Figenshau, Washington University School of Medicine, Division of Urology, St. Louis, Missouri, USA..

Yan Yan, University School of Medicine, Medical Statistics, St. Louis, Missouri, USA..

Gerald L. Andriole, Washington University School of Medicine, Division of Urology, St. Louis, Missouri, USA..

Ralph V. Clayman, UCI Medical Center, Department of Urology, Irvine, California, USA..

Jaime Landman, Columbia University Medical Center, Department of Urology, New York, USA..

References:

- 1. Yim SF, Yuen PM. Randomized double-masked comparison of radially expanding access device and conventional cutting tip trocar in laparoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:435–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lam TYD, Lee SW, So HS, Kwok SPY. Radially expanding trocar: A less painful alternative for laparoscopic surgery. J Lap Adv Surg Tech. 2000;10(5):269–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kolata RJ, Ransick M, Briggs L, et al. Technical report: comparison of wounds created by non-bladed trocars and pyramidal tip trocars in the pig. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1999;9(5):455–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Coda A, Bossotti M, Ferri F, et al. Incisional hernia and fascial defect following laparoscopic surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 1999;9:348–352 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siqueira TM, Jr, Paterson RF, Kuo RL, Stevens LH, Lingeman JE, Shalhav AL. The use of blunt-tipped 12-mm trocars without fascial closure in laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. JSLS. 2004;8(1):47–50 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Turner DJ. New generation entry devices: making the case for the radially expanding access system. Gynecol Endosc. 1999;8:391–394 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ternamian AM. A trocarless, reusable, visual-access cannula for safer laparoscopy; an update. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1998;5(2):197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhoyrul S, Vierra MA, Nezhat CR, Krummel TM, Way LW. Trocar injuries in laparoscopic surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leibl BJ, Schmedt CG, Schwarz J, et al. Laparoscopic surgery complications associated with trocar tip design: review of literature and own results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1999;9:135–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharp HT, Dodson MK, Draper ML, Doucette RC, Hurd WW. Complications associated with optical-access laparoscopic tro-cars. Obst Gyn. 2002;99(4):553–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas MA, Rha KH, Ong AM, et al. Optical access trocar injuries in urological laparoscopic surgery. J Urol. 2003;170(1):61–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown JA, Canal D, Sundaram CP. Optical-access visual obturator trocar entry into desufflated abdomen during laparos-copy: assessment after 96 cases. J Endourol. 2005;19(7):853–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. String A, Berber E, Foroutani A, Macho JR, Pearl JM, Siperstein AE. Use of optical access trocar for safe and rapid entry in various laparoscopic procedures. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:570–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rubenstein LW, Blunt WW, Jr, Lin HM, User RB, Nadler RB, Gonzalez CM. Safety and efficacy of 12-mm radial dilating ports for laparoscopic access. BJU Int. 2003;92(3):327–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bhoyrul S, Mori T, Way W. Radially expanding dilation a superior method of laparoscopic access. Surg Endosc. 1996;10:775–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feste JR, Bojahr B, Turner DJ. Randomized trial comparing a radially expandable needle system with cutting trocars. JSLS. 2000;4:11–15 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Berch BR, Torquati A, Lutfi RE, Richards WO. Experience with the optical access trocar for safe and rapid entry in the performance of laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(8):1238–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lowry PS, Moon TD, D'Alessandro A, Nakada SY. Symptomatic port-site hernia associated with a non-bladed trocar after laparoscopic live-donor nephrectomy. J Endourol. 2003;17(7):493–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shalhav AL, Barret E, Lifshitz DA, Lingeman JE, et al. Transperitoneal laparoscopic renal surgery using blunt 12-mm trocar without fascial closure. J Endourol. 2002;16(1):43–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]