Abstract

We describe the first reported use of laparoscopic splenectomy as initial treatment in high-grade blunt splenic trauma. A 21-year-old man sustained a blow to the left flank from a large construction pipe and was transferred to our hospital with a grade V splenic laceration and a grade II left peri-renal hematoma with hematuria. He was hemodynamically stable. He underwent a laparoscopic splenectomy shortly after arrival. The patient's renal injury was managed nonoperatively, and he was discharged home with no complications and has remained well.

Keywords: Laparoscopic splenectomy, Splenic trauma

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic splenectomy has been shown to have several benefits over conventional open splenectomy. A quicker return to function, earlier discharge from the hospital, less postoperative pain, and better cosmesis due to the smaller incisions have been reported by multiple authors. Decreased intraoperative blood loss and transfusion requirements have also been described.1

Laparoscopic splenectomy for splenic trauma has been described in only a few instances in the literature. The original report by Basso et al2 from Italy in 2003 describes laparoscopic splenectomy 10 days postinjury for a grade IV ruptured spleen. In the United States, Nasr et al3 in 2004 reported on a series of 4 stable patients undergoing delayed laparoscopic splenectomy for blunt trauma. They were all successfully treated and discharged without incident. We describe the successful treatment using a total laparoscopic approach shortly after admission of a young man with a grade V splenic injury.

CASE REPORT

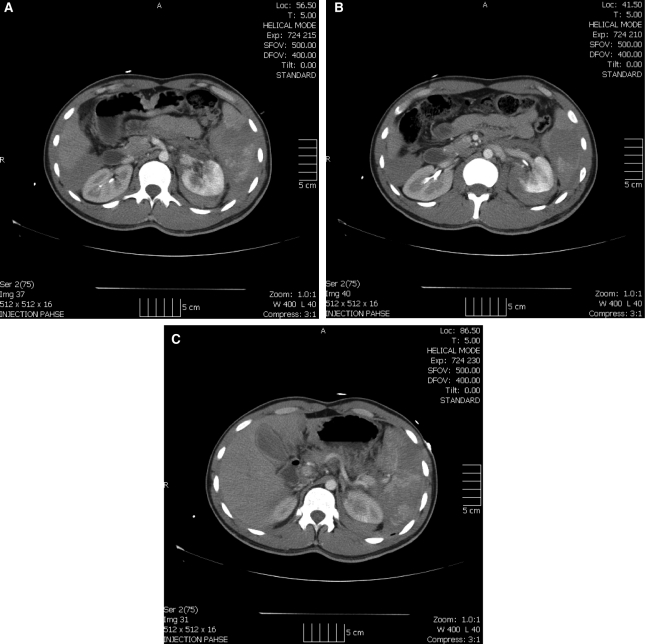

A 21-year-old man was transferred to our level 1 trauma center after sustaining a blow to his left flank from a falling construction pipe while working on an oil rig. He arrived hemodynamically stable, alert, and oriented. History revealed that this was an isolated injury in an otherwise healthy patient. His only complaint was of pain over the left flank. He had bruises over his left flank consistent with the injury. He did not have peritoneal signs, and his examination was unremarkable except for left flank tenderness. He had gross hematuria upon Foley catheter insertion. A FAST ultrasound examination revealed blood around the liver and spleen. He underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous contrast that demonstrated hemoperitoneum with an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma grade V splenic laceration and a grade II left peri-nephric hematoma4 (Figures 1, 2, and 3). There was no evidence of contrast extravasation or blush.

Figures 1.

Computed tomographic evidence of large contrast extravasation of splenic hilum.

The various management options were discussed with the patient, including observation, angiographic embolization, and splenectomy. Given the severity of his splenic injury and the presence of a renal injury that could complicate conservative management, we decided to proceed with splenectomy. The patient remained hemodynamically stable, and we elected to attempt laparoscopic splenectomy, with readiness to convert to an open operation if the patient became unstable or if we were unable to quickly obtain vascular control.

The patient was placed in the right lateral decubitus position with the bed flexed at the waist. Two 12-mm ports and one 5-mm port were used. A 10-mm camera and 5-mm atraumatic graspers were used for the initial dissection. A large hemoperitoneum was noted upon entering the abdomen. We were able to easily visualize the spleen, which was noted to have a large hematoma and venous blood oozing from the hilum (Figures 4 and 5).

The Harmonic scalpel was then used to divide the ligamentous attachments of the spleen. The spleen was carefully retracted upward with a blunt grasper and the hilum was visualized. A 15-mm endoscopic stapler (Autosuture, US Surgical, Hartford, CT) with a 60-mm gray vascular cartridge was used to transect the hilum. No bleeding occurred from the remaining splenic artery or vein, and the pancreas was visualized and protected during this process. The superior short gastric arteries were also divided by using a stapler.

The spleen was removed by using a bag inserted through a 12-mm port. The spleen required extensive morcellation to be removed due to its large size. The remaining hemoperitoneum was suctioned and a #10 Jackson Pratt drain was placed in the splenic fossa.

The patient was able to tolerate a regular diet the next day with pain controlled by oral analgesics only. He was monitored for his renal injury on the wards for the next 3 days by the trauma and urology service. The drain was removed on the third postoperative day. A follow-up renal ultrasound before discharge revealed no progression of his injury, and his hematuria resolved. His hemoglobin upon admission was 15.3. This fell to 10 on the next measurement immediately after surgery, and remained stable postoperatively. The patient did not require any transfusions. He received his vaccinations for pneumococcus, meningococcus, and H. influenzae on the day of discharge. He has remained well in follow-up visits.

DISCUSSION

The management of blunt splenic injury has evolved considerably over the past decade. Mandatory laparotomy with splenorrhaphy or splenectomy has been replaced in most cases by nonoperative management. Initially proposed in the pediatric trauma literature, close observation has become the accepted treatment of stable splenic injuries from blunt trauma.5 Failure rates for nonoperative treatment are very variable, ranging from 10% to 40%.6 Patients with severe (grade III and higher) splenic injuries have a higher failure rate than with injuries of lesser severity. They also have a higher transfusion requirement and increased morbidity and mortality.7 Several recent trials have shown that blood transfusion causes a dose-dependent immunosuppression and significantly increased mortality in critically ill patients, including trauma victims.8,9 Further risks of nonoperative treatment include delayed splenic rupture, persistent pain, and prolonged immobilization which is contraindicated in a group at high risk for venous thromboembolism. The need for bed rest and monitoring often requires prolonged hospital stays.

Splenic artery angio-embolization has been described as an alternative to operative management of splenic injuries. This has improved the rate of splenic salvage to greater than 90% in several series. Lower grades of injury severity correspond to higher success rates for this approach.5,10 Complications of angioembolization include the need for delayed splenectomy due to splenic infarction, infection, abscess, or persistent pain. The rate of these complications has been described as high as 33% in some series.11

Splenectomy is not indicated for all of the injuries, and angiographic embolization is an acceptable option to further define the injury and prophylactically reduce the rate of observation. We believe that in those institutions where a vascular surgeon or radiology specialist for embolization is available 24 hours a day, this can be the best option. When a vascular surgeon or radiologist specialist is not available for patients who are questionable, splenectomy, in our opinion, is still the best option, particularly if the splenectomy can be performed laparoscopically.

Prevention of overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis (OPSI) has often been cited as a reason for advocating splenic preservation. However, the incidence of OPSI in adults, in contrast with children, is very low (<1%) and with modern vaccination and antibiotics is expected to decline further. In adult patients, the risks of transfusion and delayed splenic rupture, abscess, and pain should be weighed against the risk of OPSI in determining the best approach to severe splenic injuries. The role of laparoscopy in blunt trauma has yet to be defined. In experienced hands, it has been shown to reduce the negative laparotomy rate and identify and treat diaphragmatic and visceral injuries.12 Several authors have used laparoscopy to apply hemostatic agents to solid organ lacerations and perform spleen preserving procedures in lower grade injury.13,14 We believe that if there is a splenic injury and no other injury in the abdomen, as shown by CT and FAST scans, the laparoscopic approach is feasible, even though the gold standard is still considered exploratory laparotomy. We believe any injury of the hilum, specifically in the vein in the splenic area, is an indication for laparoscopy while the injury of the artery could not be a good indication at this point. Laparoscopic splenectomy has not been well described in patients with splenic trauma. To our knowledge, this is the first report of laparoscopic splenectomy as first-line treatment for a grade V injury in a trauma patient. Nasr et al3 reported the successful use of laparoscopic splenectomy in 4 patients. These patients were all stable with isolated splenic injuries. They were operated on after an initial period of stabilization and nonoperative treatment. Two patients had a grade III and one had a grade I injury. One patient had previously undergone splenic artery embolization and re-presented with delayed splenic rupture. The grade of injury in this case was not stated. They had no complications from the laparoscopic approach.3 Based on our experience, we would like to point out that laparoscopic splenectomy can be safely performed in a high-grade injury by an experienced surgeon and should be considered in stable patients. Laparoscopic splenectomy is not the gold standard. The reason why we reported this case is to raise the question of whether we are ready to move into laparoscopy. We do not believe that we are at this point, but it is good to raise controversy and maybe in the future, a single injury to the spleen with no other injuries reported by CT and FAST in patients who are hemodynamically stable could be an indication for laparoscopic splenectomy. In our case, a grade V injury was reported with the CT scan, and there was a big hematoma at the level of the hilum. We believe retrospectively that the hematoma made the bleeding decrease, and no more bleeding was coming out from the hilum. No vascular surgeon or radiologist was available; therefore, embolization was not an option. We agree that there is nothing in the literature that requires immediate splenectomy in a young, healthy, stable patient with a high-grade injury based on the CT scan, but laparoscopic exploration in trauma15 is an acceptable option.

Patients with high-grade splenic injuries are more likely to fail conservative treatment. Nonoperative treatment is associated with several risks, including the risk of blood transfusion. Transfusion is being increasingly recognized as an independent factor in poor outcomes, and avoidance of transfusion is likely to become a priority in managing stable trauma patients. Laparoscopic splenectomy should be considered as an option in these patients, either on admission or after failure of nonoperative management. The benefits of smaller incisions, less postoperative pain, and the potential for earlier discharge from the hospital should be weighed when deciding on an operative approach.

The risk of injury to the tail of the pancreas during a laparoscopic dissection of the splenic hilum in the presence of a hematoma/hemoperitoneum is not different from an exploratory laparotomy in experienced hands. We believe that with the laparoscopic technique, the experience of the surgeon and the visualization of the hilum are of utmost importance, and the pancreatic tail can be visualized well and decrease the risk of the pancreatic tail injury.

Our patient remained in the hospital for 3 days solely for observation of his associated renal injury. He was able to resume a regular diet immediately and had minimal requirements for pain medication. A patient with an isolated splenic injury would likely be stable enough to be discharged the next day, following laparoscopic surgery.

CONCLUSION

Laparoscopic splenectomy can be successfully used as an immediate treatment option in hemodynamically stable patients with severe splenic injury.

References:

- 1. Silecchia G, Raparelli L, Casella G, Basso N. Laparoscopic splenectomy for non-traumatic diseases. Minerva Chir. 2005; 60 (5): 363–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Basso N, Silecchia G, Raparelli L, Pizzuto G, Picconi T. Laparoscopic splenectomy for ruptured spleen: lessons learned from a case. J Laparoendoscopic Adv Surg Tech A. 2003; 13 (2): 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nasr WI, Collins CL, Kelly JJ. Feasibility of laparoscopic splenectomy in stable blunt trauma: a case series. J Trauma. 2004; 57: 887–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore EE, Shackleford SR, Pachter SL, et al. Organ injury scaling: Spleen, liver, kidney. J Trauma. 1989; 29 (12): 1664–1666 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haan JM, Bochicchio GV, Kramer N, Scalea TM. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5 year experience. J Trauma. 2005; 58 (3): 492–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Knudson MM, Maull KI. Nonoperative management of solid organ injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1999; 79: 1357–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jalovec LM, Boe BS, Wyffels PL. The advantages of early operation with splenorrhaphy versus nonoperative management for the blunt splenic trauma patient. Am Surg. 1993; 59: 698–705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McIntyre L, Herbert PC, Wells G, et al. Is a restrictive transfusion strategy safe for resuscitated and critically ill trauma patients? J Trauma. 2004; 57 (3): 563–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vincent JL, Baron JF, Reinhart K, et al. Anemia and blood transfusion in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2002; 25; 288 (12): 1499–1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haan JM, Biffl W, Knudson MM, Davis KA, Oka T, Majercik S, Dicker R, Marder S, Scalea TM; Western Trauma Association Multi-Institutional Trials Committee. Splenic embolization revisited: a multicenter review. J Trauma. 2004; 56 (3): 542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cooney R, Ku J, Cherry R, et al. Limitations of splenic angioembolization in treating blunt splenic injury. J Trauma. 2005; 59 (4): 926–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chol YB, Lim KS. Therapeutic laparoscopy for abdominal trauma. Surg Endosc. 2003; 17 (3): 421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shen HB, Lu XM, Zheng QC, Cai XT, Zhou H, Fei KL. Clinical application of laparoscopic spleen-preserving operation in traumatic spleen rupture. Chin J Traumatol. 2005; 8 (5): 293–296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Orcalli F, Elio A, Veronese E, Frigo F, Salvato S, Residori C. Conservative laparoscopy in the treatment of posttraumatic splenic laceration using microfiber hemostatic collagen. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998; 12: 600–603 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simon R, Rabin J, Kuhls D. Impact of increased use of laparoscopy on negative laparotomy rates after penetrating trauma. J Trauma. 2002; 53: 297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]