Abstract

Gastric diverticula are rare and occasionally symptomatic. A sensation of fullness in the upper abdomen immediately after meals is the most common symptom. Dyspepsia and vomiting are less common. Ulceration with hemorrhage or perforation has been reported. If it is thought that complaints can be ascribed to the diverticulum and if proton pump inhibitors do not relieve symptoms, surgical resection is an option. Knowledge of the pitfalls in diagnosis and treatment of a gastric diverticulum are essential for successful and complete relief of symptoms. We report a successful laparoscopic approach as a minimally invasive solution to a symptomatic gastric diverticulum.

Keywords: Gastric diverticulum, Symptomatic, Laparoscopic resection, Minimally invasive

INTRODUCTION

Gastric diverticula are rare and incidentally found during examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Although most patients are asymptomatic, occasionally, abdominal symptoms occur, ranging from vague pain, epigastric fullness, bleeding, or perforation.1,2 If symptoms persist despite the use of proton pump inhibitors, surgical resection is a treatment option. We present a patient with an unusual complaint of a gastric diverticulum, discuss the pitfalls in management and report a minimally invasive solution.

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old woman visited our outpatient clinic because of severe “foetor ex ore.” At first, she experienced a foul smelling breath only when burping, later it was a constant and invalidating complaint. At night, she would occasionally vomit. Proton pump inhibition did not relieve her symptoms.

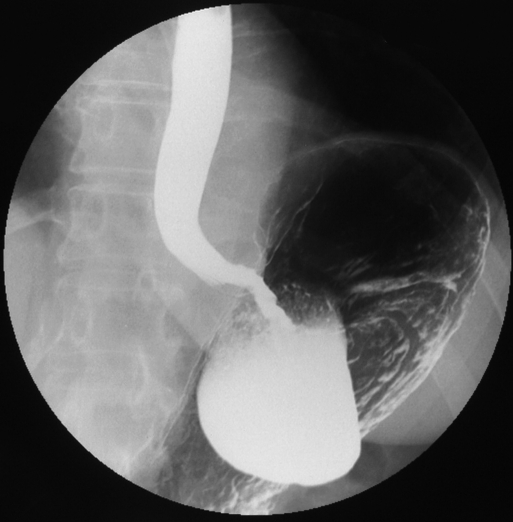

Endoscopy showed a diverticulum 5cm in length, high in the posterior corpus-fundic region of the stomach, with stasis of food residue. A barium study confirmed a posteriorly located gastric diverticulum 2cm from the gastroesophageal junction (GOJ) (Figure 1). Although contrast passed through the stomach quickly, retention in the diverticulum was evident.

Figure 1.

A barium study reveals a posteriorly located gastric diverticulum 2cm from the gastroesophageal junction (GOJ).

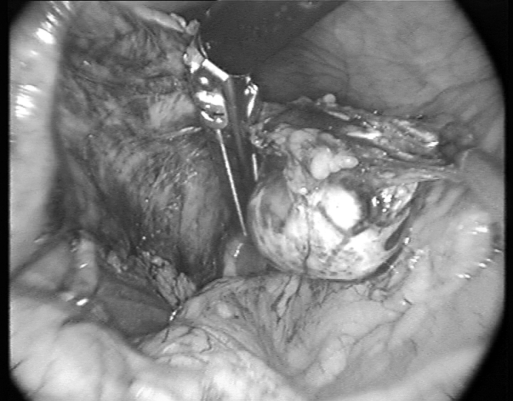

The food residue and contrast retention in the diverticulum were believed to explain the patients “foetor ex ore,” and a laparoscopic resection was decided on. With the patient under general anesthesia, laparoscopic access was obtained to the peritoneal cavity by an open subumbilical trocar placement. An additional four 10-mm trocars were placed in similar fashion as for a fundoplication. A liver retractor (Endo Paddle Retract, US Surgical Corp., Norwalk, CT) was used to obtain a good upper abdominal view. Because inspection of the stomach did not reveal a diverticulum at the anterior surface, the bursa omentalis was opened by dividing the gastrocolic omentum with a LigaSure (Atlas, Boulder, CO). The stomach was retracted ventrally and to the right to inspect the posterior part of the greater curvature. No diverticulum was identified, and short gastric vessels were divided sequentially. Dissection was continued up to the cardia, and the diverticulum was found 2cm distally from the GOJ at the cranial boarder of the pancreas. Dissection from its avascular adhesions to the retroperitoneum was performed until the saccular structure was clearly identified (Figure 2). The diverticulum was resected at the neck with the EndoGIA (Universal, US Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CO). The neck of the diverticulum was retracted though the umbilical skin incision, a tip of the stapler line was cut open, the excrements were aspirated from the diverticulum, and the collapsed diverticulum could be extracted though the small umbilical incision (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

The gastric diverticulum dissected from its vascular adhesions to the retro peritoneum and its resection at the neck with the EndoGIA (Universal, Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CO).

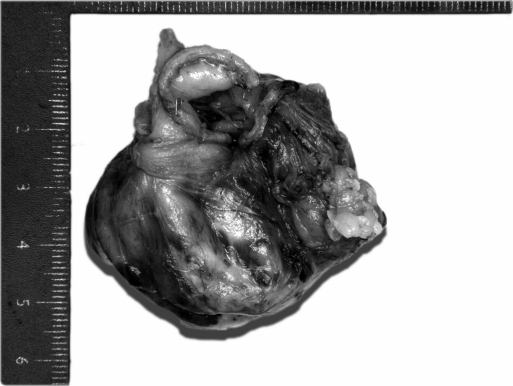

Figure 3.

Histology showed a gastric diverticulum of 5.5×4×2.5 cm.

Histology showed a gastric diverticulum of 5.5×4×2.5 cm with normal mucosa, a thickened muscularis mucosae, and a thin and partly discontinuous muscularis propria.

The procedure was uneventful. The patient recovered quickly without complications. She experienced no more “foetor ex ore” or nightly vomiting.

DISCUSSION

Gastric diverticula are an uncommon form of diverticular disease. The incidence ranges from 0.02% in autopsy studies to 0.01% to 0.11% at endoscopy.1,2 But because these diverticula are usually asymptomatic, it is now believed that the true prevalence of gastric diverticula is much higher.

Akerlund3 classified gastric diverticula as congenital and acquired. The congenital gastric diverticulum is a “true diverticulum” and involves all layers of the gastric wall. It is the most common gastric diverticulum typically located at the posterior wall just below the GOJ. The acquired variety lacks the muscular or serosal layer “false diverticulum” and is mostly located in the distal one third of the stomach, especially in the prepyloric region. Either traction or pulsion diverticula may be present, often caused by other diseases, inflammatory processes, or tumors.

Most gastric diverticula are known to be asymptomatic.4 Occasionally, a sensation of fullness in the upper abdomen immediately after meals occurs. Dyspepsia and vomiting are less common.1,2 Ulceration with hemorrhage or perforation are rare complications but have been reported. Only twice has an invasion with adenocarcinoma been reported.5,6

In about 10% of patients with a true diverticulum, surgery is required. Diverticula exceeding 4cm are more prone to produce complications and tend to respond less favorably to medication. In case of chronic inflammation, ulceration, and hemorrhage, surgical treatment is a sound indication.7 In patients suffering from abdominal pain or a sensation of fullness and early satiety, indication for surgery is less clear. Essential for successful treatment with complete relief of symptoms is the association of the symptoms with the diverticulum. Palmer1 found that, in 30 of 49 symptomatic patients with a gastric diverticulum, symptoms were attributable to other gastrointestinal diseases. Resection of gastric diverticula in all patients will lead to unsatisfactory results.4

Another important pitfall is to definitely localize the diverticulum. Before the laparoscopic era, the surgical approach was through a median upper laparotomy or subcostal incision. Even the open approach can be challenging because the diverticulum is often collapsed and hidden in the splenic bed. A resection of the wrong part of the stomach has been described.4

Laparoscopically, access to the posterior gastric fundus is relatively easy by dividing the gastrocolic ligament. In our experience, the diverticulum was found by continuing the dissection up to the cardia by dividing the short gastric vessels. If even then the diverticulum is not found, the procedure can be combined with intraoperative gastroscopy or the stomach can be insufflated with 0.9% saline solution via a nasal tube while the antrum is closed by compression.

Laparoscopic resection has been reported to be feasible and produced an excellent outcome in previous cases.7,10 In one case, however, laparoscopic resection led to mixed results, reflecting the dilemma of ascribing nonacute symptoms to a gastric diverticulum. In our case, recovery was uneventful, and relief of the somewhat unusual symptoms was complete.

CONCLUSION

If laparoscopic experience is available and familiarity with the diaphragmatic hiatus exists, we recommend laparoscopic resection, as a minimally invasive solution to a symptomatic gastric diverticulum.

Contributor Information

S. C. Donkervoort, Department of Surgery, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

L. C. Baak, Department of Gastroenterology, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

J. L. G. Blaauwgeers, Department of Pathology, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

M. F. Gerhards, Department of Surgery, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

References:

- 1. Palmer ED. Gastric diverticulosis. Am Fam Physician. 1973; 7: 114–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Raffin SB. Diverticula, rupture and volvulus. In: Sleigenger MH, Fordtran JS, eds. Gastrointestinal Disease, Pathophysiology Diagnosis, Management. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders WB; 1989: 735–742 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akerlund D. Gastric diverticulum. Acta Radiol. 1923; 2: 476–485 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anaise D, Brand DL, Smith NL, Soroff HS. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment of a symptomatic gastric diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984; 30(1): 28–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fork FT, Toth E, Lindstrom C. Early gastric cancer in a fundic diverticulum. Endoscopy. 1998; 30(1): S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adachi Y, Mori M, Haraguchi Y, Sugimachi K. Gastric diver-ticulum invaded by gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987; 82(8): 807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fine A. Laparoscopic resection of a large proximal gastric diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 30: 28–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mc Kay R. Laparoscopic resection of a gastric diverticulum: a case report. JSLS. 2005; 9(2): 225–228 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim SH, Lee SW, Choi WJ, Choi IS, Kim SJ, Koo BH. Laparoscopic resection of gastric diverticulum. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999; 9(1): 87–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Alberts MS, Fenoglio M. Laparoscopic management of gastric diverticulum. Surg Endosc. 2001; 15(10): 1227–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]