Abstract

Background:

Superior mesenteric artery (Wilkie's) syndrome is a rare condition. Only 400 cases have been reported so far. The symptoms may be acute or chronic, the chronic form being more common. Vomiting is the most common symptom. About 15 causal factors have been found. Conservative management is the rule for acute cases. Surgery is indicated for chronic cases and failure of conservative management. Laparoscopy has been used in only 8 cases so far.

Case Report:

We report the ninth case of superior mesenteric artery syndrome managed by laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy. The patient was a 14-year-old boy with chronic symptoms since childhood. The procedure was relatively straightforward. The case is being reported for its rarity and the possibility of laparoscopic management.

Discussion:

Laparoscopic severing of Treitz's ligament is another surgical option, though gastrojejunostomy is of no use. Conservative management is useful only in acute cases.

Conclusion:

Duodenojejunostomy is the procedure of choice and is effective in 90% of patients. We conclude that it is very effective in this condition, especially laparoscopically.

Keywords: Chronic vomiting, Superior mesenteric artery syndrome, Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy

INTRODUCTION

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome was first described in 1842 by Von Rokitansky,1 who proposed that the cause was obstruction of the third part of the duodenum as a result of arteriomesenteric compression and vascular compression of the duodenum. Bloodgood, in 1907, was the first to suggest that duodenojejunostomy could be performed as a treatment.2 In 1921, Wilkie3 published a report on duodenojejunostomy for SMA syndrome and concluded that this was the treatment of choice. He also coined the term “chronic duodenal ileus,” which we now know is a misnomer. It was Harold Ellis who first said SMA syndrome is the most appropriate term.1 Despite the fact that about 400 cases are described in the English language literature, many researchers have doubted the existence of SMA syndrome as a real entity; indeed, some investigators have suggested that SMA syndrome is overdiagnosed, because it is confused with other causes of megaduodenum. Nonetheless, the entity often poses a diagnostic dilemma; its diagnosis is frequently one of exclusion.

CASE REPORTS

The patient was a 14-year-old boy who presented with chronic upper abdominal symptoms for 10 years, ie, epigastric pain, nausea, voluminous vomiting (bilious and partially digested food), postprandial discomfort, and early satiety. The symptoms were relieved on vomiting and aggravated when he was in the supine position. He was severely malnourished (height and weight were low for his age). Plain radiogram showed a dilated stomach and C-loop of duodenum, hypotonic duodenography ultrasonogram report showed marked distension of the stomach, duodenum dilated up to the third part and seen to taper at the level of SMA. Marked “to and fro” peristalsis was seen. Endoscopy showed Grade 2 esophagitis, gastric bile reflux, and a dilated second part of the duodenum. Barium meal study also confirmed duodenal obstruction at the level of the superior mesenteric vessels. The barium flow abruptly cuts off at this level (Figure 1). A Hayes test was positive, and the lumen could be demonstrated by free flow with a change of posture. No intrinsic lesion was noted in the duodenal wall or in the lumen. The possibility of SMA syndrome was thus established. The patient was put on conservative treatment for 4 days. This included nil per oral, GI decompression (nasogastric tube), and intravenous fluids. Enteral feeding through the nasogastric tube passed distal to the obstruction was also done. The patient started to vomit after he was allowed to eat. Because the response was poor and failed to increase body weight, we decided to operate on him. The plan was laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy. The surgeon was positioned in between the legs; camera surgeon stood to the right of the patient; another assistant (for retraction) and a scrub nurse stood to the left of the patient

Figure 1.

Barium meal picture.

The patient was placed supine, in a 20° head-up position. Pneumoperitoneum was established using a Veress needle technique. A 10-mm port, at the umbilicus for a 30° telescope, was first inserted. Then a 5-mm port in the epigastrium for liver retraction, a 5-mm port in the right lumbar area for a left-hand working port, and a 10-mm port in the left lumbar area for a right-hand working port were inserted. The transverse colon was lifted up to expose the dilated, bulging second and third parts of the duodenum (Figure 2). The second and third parts of the duodenum were found in the infracolic compartment extending caudally down to the level of the ileocecal junction. This is most likely due to distension of the duodenum rather than to a congenital anomaly. The visceral peritoneum covering this was cut with scissors, and this part of the duodenum was freely mobilized. A loop of jejunum about 7 cm to 10 cm from the duodenojejunal flexure was brought up to the duodenum (Figure 3). The most caudal portion of the second part of the duodenum was selected for anastomosis to create the most dependant stoma. Stay sutures were applied intracorporeally with 2- 0 silk. A small 1-cm opening was made in both the duodenum and jejunum. One of the jaws of a 45-mm EndoGIA stapler (white cartridge with 25-mm staple pins, Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) was introduced into the lumen of the jejunum, and the other jaw was introduced into the lumen of the duodenum. The stapler was then fired. The common opening thus created was closed intracorporeally with 2- 0 Vicryl sutures in a single layer (Figure 4). The anastomosis was side-to-side, and the size of thelumen was 4.5 cm. The intermesenteric gap was obliterated with a few interrupted silk sutures. The surgery time was 110 minutes, postoperative pain required parenteral analgesics for only the first postoperative day (POD), time to first flatus was 48 hours, and length of hospital stay was 5 days. Cosmesis was better, which was especially important because the patient was a 14-year-old boy. Postoperative contrast study showed free flow to the jejunum. A liquid diet was started from the second POD and a solid diet from the fourth POD. The patient was discharged on the fifth POD. Gastrografin swallow was done 6 months after surgery, and no hold-up of contrast occurred. There is no recurrence of symptoms so far.

Figure 2.

Exposing the dilated duodenum through the mesocolon.

Figure 3.

Placing the dilated duodenum and jejunum together to facilitate anastomosis.

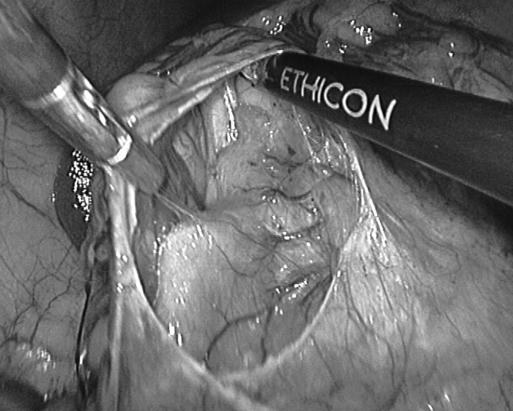

Figure 4.

Completed anastomosis.

DISCUSSION

In the United States, the precise incidence of this entity is unknown. In a review of the literature, approximately 0.013% to 0.3% of the findings from upper GI tract barium studies support a diagnosis of SMA syndrome.4 Females are more affected by SMA syndrome. In one large series of 75 patients with SMA syndrome, two thirds of the cases involved women, with an average age of 41 years; one third of cases involved men, with an average age of 38 years.5 The SMA syndrome usually occurs in older children and adolescents. SMA syndrome results from the compression of the third portion of the duodenum between vessels and the vertebrae and paravertebral muscles by SMA, which takes its origin from the abdominal aorta at the level of the first lumbar vertebra and crosses the duodenum. Any factor that sharply narrows the aortomesenteric angle to approximately 6° to 16° can cause entrapment and compression of the third part of the duodenum, resulting in SMA syndrome. In addition, the aortomesenteric distance in SMA syndrome is decreased to 2cm to 8mm (normal is 10 to 20 mm). The acute type is less common and may present as a surgical emergency. Peptic ulcer disease has been noted in 25% to 45% of the patients and hyperchlorhydria has been noted in 50%.5 Table 1 provides a list of some causal factors. Other causes are rapid linear growth without compensatory weight gain (in adolescence), an abnormally high, fixed position of the ligament of Treitz with an upward displacement of the duodenum and unusually low origin of the SMA.

Table 1.

Important Causal Factors

The diagnosis of SMA syndrome is difficult. Upper GI endoscopy is necessary to exclude mechanical causes of duodenal obstruction. However, the diagnosis of SMA syndrome may be missed. Upper GI study with barium reveals characteristic dilatation of the first and second parts of the duodenum, with an abrupt vertical or linear cutoff in the third part with normal mucosal folds and a delay of 4 hours to 6 hours in gastroduodenal transit. In equivocal cases, hypotonic duodenography may depict the site of obstruction and dilation of the proximal duodenum, with antiperistaltic waves within the dilated portion. Conservative measures include nil per oral, nasogastric aspiration and decompression, intravenous fluids, and nutrition. The success rate is 100% with medical management only in the acute presentation of SMA syndrome. Surgical intervention is indicated when conservative measures are ineffective, particularly in patients with a long history of progressive weight loss, pronounced duodenal dilatation with stasis, and complicating peptic ulcer disease. Duodenojejunostomy is the most frequently used procedure, and it is successful in about 90% of cases.9 The use of laparoscopic surgery that involves lysis of the ligament of Treitz and mobilization of the duodenum, with good results, has been reported. Although it does not involve opening of the GI tract, it requires the division of some small vessels of the distal duodenum. Segmental ischemia due to this is purely theoretical. Berchi et al10 also had good results with laparoscopic severing of Treitz's ligament in a pediatric patient. Gersin et al11 were the first to report laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for the treatment of SMA. According to an Internet search, 4 cases of laparoscopic division of the ligament of Treitz and 8 cases of laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for SMA syndrome have been reported so far.12–15

Gastrojejunostomy has no role in the treatment of chronic SMA syndrome because the results are unsatisfactory. No complications were encountered in our patient. Recurrence of SMA syndrome in an otherwise healthy adult patient was unknown until one case report in 1995.15

CONCLUSION

SMA is a rare disorder and surgical intervention is indicated when conservative measures fail. Conventional open surgery has shown good results. Although the role of laparoscopy in managing SMA syndrome is not clearly defined, laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy is a feasible option. It provides all the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, and it is technically simple as well.

References:

- 1. Cheshire NJ, Glazer G. Diverticula, volvulus, superior mesenteric artery syndrome and foreign bodies. In: Zinner MJ, Schwarts SI, Ellis H. eds. Maingot's Abdominal Operations. Vol. 1 10th ed. Norwwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1997; 913–939 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bloodgood JC. Acute dilatation of the stomach: gastromesenteric ileus. Ann Surg. 1907; 46: 736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilkie DPD. Chronic duodenal ileus. Am J Med Sci. 1927; 173: 643–649 [Google Scholar]

- 3a. Baltazar U, Dunn J, Floresguerra C. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: an uncommon cause of intestinal obstruction. South Med J. 2000; 93(6): 606–608 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bermas H, Fenoglio ME. Laparoscopic management of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 2003; 7(2): 151–153 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nana AM, Closset J, Muls V, et al. Wilkie's syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2003; 17(4): 659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barnes JB, Lee M. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in an intravenous drug abuser after rapid weight loss. South Med J. 1996; 89: 331–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Roth EJ, Fenton LL, Gaebler-Spira DJ, et al. SMA syndrome in acute traumatic quadriplegia: case reports and literature review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1991; 72(6): 417–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Willett A. Fatal vomiting following application of plaster of Paris bandage in a case of spinal curvature. St Barts Hosp Rep. 1878; 14: 333– [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richardson WS, Surowiec WJ. Laparoscopic repair of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Am J Surg. 2001; 181(4): 377–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berchi FJ, Benavent MI, Cano I, Portela E, Urruzuno P. Laparoscopic treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. Pediatr Endosurg Inn Tech Sep. 2001; 5(3): 309–314 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gersin KS, Heniford BT. Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 1998; 2(3): 281–284 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim IY, Cho NC, Kim DS, Rhoe BS. Laparoscopic duodenojejunostomy for management of superior mesenteric artery syndrome: two cases report and a review of the literature. Yonsei Med J. 2003; 44(3): 526–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. James RH, Richard MG, Garth HB. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome: diagnostic criteria and therapeutic approaches. Am J Surg. 1984; 148: 630–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kingham TP, Shen R, Ren C. Laparoscopic treatment of superior mesenteric artery syndrome. JSLS. 2004; 8(4): 376–379 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raissi B, Taylor BM, Taves DH. Recurrent superior mesenteric artery (Wilkie's) syndrome: a case report. Can J Surg. 1996; 39(5): 410–416 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]