Abstract

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is an uncommon event. We report a case of an 84-year-old female with a giant paraesophageal hernia who presented with coffee ground emesis and on esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) demonstrated findings consistent with acute esophageal necrosis and a giant paraesophageal hernia with normal-appearing gastric mucosa. She was managed conservatively with bowel rest, parenteral nutrition, and continuous intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI). After significant improvement in the gross appearance of her esophageal mucosa, surgery was performed to reduce her giant paraesophageal hernia. The patient's postoperative course was uneventful, and she was discharged home on postoperative day 6, tolerating a normal diet. The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube was removed in clinic 2 months postoperatively.

Keywords: Esophagus, Ischemia, Pathophysiology, Hernia

INTRODUCTION

Diffuse acute esophageal necrosis is a rare event with only a few reported cases. Although the cause and pathophysiology of this entity are unclear, ischemia is often thought to play a major role. Emergent surgical intervention following stabilization is clearly indicated by the presence of frank necrosis and perforation. Some cases without trans-mural injury have been managed conservatively and resolve without long-term consequences, although mortality can be as high as 35% related to the underlying illnesses.1

CASE REPORT

An 84-year-old female presented to a local hospital with a 1-week history of coffee ground emesis and a 4-day history of persistent vomiting. She was noted to have an elevated white blood cell count of 18.5 K/μL and a decrease in hemoglobin from 12.9 to 11.2 g/dL. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) was performed, revealing diffuse dusky esophageal mucosa with sloughing as well as the presence of a paraesophageal hernia. A small non-bleeding gastric ulcer was also noted, but the gastric mucosa was otherwise pink and healthy appearing. The patient was then transferred in stable condition for possible esophagectomy at our tertiary facility.

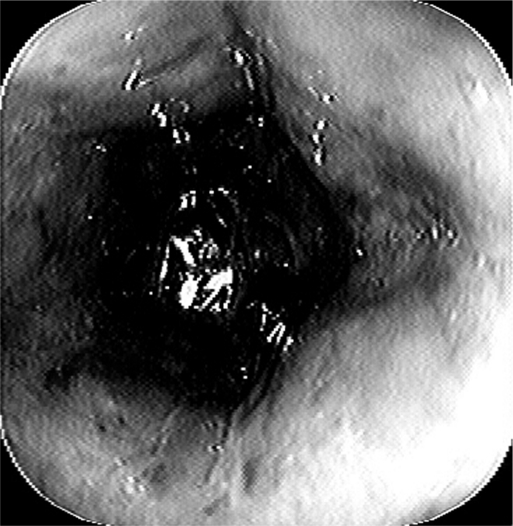

Her past medical history was significant for hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency, degenerative joint disease, and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Her surgical history included appendectomy, cholecystectomy, vaginal hysterectomy, and total hip replacement. At the time of her transfer, her medications included the fentanyl patch and intravenous fluconazole, metoprolol, pantoprazole, piperacillin, and tazobactam. On physical examination, she appeared in no acute distress. She was afebrile with a regular pulse of 96 bpm and blood pressure of 198/97 mm Hg. Her abdomen was soft, nontender, and nondistended with normoactive bowel sounds. Her laboratory data revealed a WBC of 14.6 K/μL with a left shift, hematocrit of 36 mL/dL, and creatinine of 1.8 mg/dL. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen demonstrated a large paraesophageal hernia with organoaxial gastric volvulus. No mediastinal air, intraabdominal free air or fluid, bowel thickening, or fat stranding was present. A repeat EGD performed 24 hours after admission demonstrated pale cervical esophageal mucosa with a dusky, friable appearance, progressively worsening down the length of the esophagus. The mucosa was essentially normal beyond the gastroesophageal junction with pink, healthy gastric mucosa and no evidence of bleeding or ulceration (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The endoscopic view demonstrated progressive dusky and discolored esophageal mucosa.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and was treated with intravenous hydration, piperacillin, tazobactam, pantoprazole, and parenteral nutrition. Her vitals and physical examination remained stable and her WBC normalized. On hospital day 4 and 7, repeat EGD showed progressive improvement in the dusky appearance of her distal esophageal mucosa. Subsequently, on hospital day 12, she was taken to the operating room for an elective laparoscopic reduction of her paraesophageal hernia, excision of the hernia sac, and primary repair of the crural defect. Fundoplication was not performed due to the prior esophageal ischemia and concern for the integrity of the esophageal wall. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement was also performed simultaneously to anchor the stomach to the anterior abdominal wall. Her postoperative course was uncomplicated, and she was discharged home in stable condition on postoperative day 6. On her follow-up clinic visit 1 week postoperatively, she was doing well, tolerating both solids and liquids. The percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube was never used for alimentation and was removed locally 2 months postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we describe a case of diffuse ischemic esophageal necrosis in an 84-year-old female with a giant asymptomatic paraesophageal hernia. Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is often referred to as “black esophagus” or necrotizing esophagitis. Goldenberg2 first described this entity in 1990 in the era of modern endoscopy. It is characterized by the presence of diffuse dark pigmentation associated with esophageal mucosal necrosis in the absence of caustic or corrosive agent ingestion. It is an extremely rare disease entity with an estimated prevalence of only 0.2% in one autopsy study.3 In another autopsy study4 with 1000 subjects, not a single case was identified.

The inciting event of AEN is unknown in most cases. Potential causes include ischemia, gastric outlet obstruction, trauma, and infection.1 Other conditions that are associated with AEN include hyperglycemia1 and underlying malignancy.1,5 The pathogenesis of AEN remains unclear although an ischemic event likely plays a role in precipitating the event. In support of this theory, reduction of esophageal blood perfusion experimentally can result in extensive esophageal mucosal injury that can resolve if perfusion is restored.6 In addition, AEN tends to occur in the distal third of the esophagus, a relatively hypo-vascular “watershed region” relative to the proximal esophagus. It is unlikely that one single factor is entirely responsible for this disease entity known as AEN.

Patients with AEN can present with upper GI bleeding that may develop rapidly after an inciting event.1,5 Definitive diagnosis is made by direct mucosal visualization on upper endoscopy. In initial stages, black discoloration of the esophageal mucosa with friable hemorrhagic areas can be observed. A distinct transition to normal-appearing mucosa occurs at and below the gastroesophageal junction. In the later stages of AEN, the mucosa can be partially covered with thick, white exudates of sloughed mucosa. To differentiate AEN from other conditions that mimic AEN secondary to black discoloration of the esophagus, biopsies should be performed and reveal severe necrosis of the mucosa and submucosa in the case of AEN.

CONCLUSION

The most common presenting symptom of AEN is acute, upper GI bleeding, and resuscitation is the first priority. Treating the underlying disorder, if known, is the next step in management. Adequate intravenous hydration and parenteral nutrition should be instituted as well as aggressive acid suppression with an intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Nasogastric decompression can be instituted if persistent vomiting, gastric outlet obstruction, or bleeding is present. Antibiotics are indicated only in select patients who demonstrate signs of sepsis or who are immunocompromised. Timing of follow-up endoscopies is dictated by a patient's clinical status. Approximately 25% have long-term complications, such as esophageal stricture, the most common complication.7 Approximately 35% of patients with AEN die acutely either due to the underlying illness or as a direct result of this condition. Most patients with AEN without an inciting event can be conservatively managed with bowel rest, total parenteral nutrition, intravenous PPIs and +/− intravenous antibiotics; the decision has to be individualized.

References:

- 1. Lacy BE, Toor A, Bensen SP, Rothstein RI. Acute esophageal necrosis: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;96:493–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Etienne JP, Roge J, Delavierre P, Veyssier P. Necroses de L'oesophage d'origine vasculaire. Semaine des Hopitaux. 1969;45:1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Postlethwait RW, Musser AW. Changes in the esophagus in 1,000 autopsy specimens. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1974;68:953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ben Soussan E, Savoye G, Hochain P, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: a 1-year prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:213–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haviv YS, Reinus C, Zimmerman J. “Black esophagus” a rare complication of shock. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2432–2434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kram M, Gorenstein L, Eisen D. Acute esophageal necrosis associated with gastric volvulus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:610–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]