Abstract

Background:

The incarcerated appendix in the femoral hernia represents a rare clinical case that was first described by the Frenchman de Garengeot in 1731. Besides the open procedures, laparoscopy presented itself as a treatment option.

Case Report:

Our case concerns a 38-year-old patient with a right femoral hernia with an inflamed incarcerated appendix. Because of the clinically inconclusive finding, we chose transperitoneal preperitoneal hernia repair (TAPP) combined with a laparoscopic appendectomy. The intra- and postoperative course was uneventful. This case shows that a laparoscopic procedure is possible even in the case of an incarceration in conjunction with an appendicitis that has not spread to the adjacent peritoneum.

Discussion:

Compared with open interventions, the subjective social advantages (shorter hospital stay, earlier return to work, less need for pain killers, and others) of laparoscopic hernia treatment have been extensively studied. The use of both methods in the case of an incarcerated hernia is open to dispute, though various small series confirm the feasibility.

Conclusion:

Here, TAPP seems to be the more reliable method in terms of patient safety because of the simultaneous possibility of using laparoscopy.

Keywords: de Garengeot, Femoral hernia, Appendicitis, TAPP

INTRODUCTION

The race for the first appendectomy in the 19th century did not produce a winner. From today's viewpoint, it can be assumed that Lawson Tait performed the first appendectomy via abdominal access in 1880.1 Many of his surgical predecessors had merely performed drainage of a paratyphlitic abscess, without actually removing the appendix.

More than a century earlier, other surgeons already had to deal with the appendix in unusual ways. On December 6, 1735, at London's St. George Hospital, the 11-year-old patient Hanvil Anderson had his appendix taken out in a rather uncommon manner. During exploration of a right-sided inguinal hernia, the surgeon Claudius Amyand decided that the incarcerated appendix was the cause of the femoral inflammatory process. The appendectomy was successful, and the patient recovered—a remarkable feat considering the lack of analgesia and hygiene at that time, but, as expected, his hernia recurred.1–3

Earlier yet, Paris surgeon Rene Jacques Croissant de Garengeot diagnosed an incarcerated appendix contained in a femoral hernia. His description of this clinical picture dates to the year 1731, though he did not perform an appendectomy during the intervention. Finally, in 1785, the first appendectomy of a de Garengeot hernia was performed by Hevin.2 While the Amyand hernia, similar to the Littre hernia, has become a familiar term in the profession, the name of the Paris surgeon, unjustifiably, has not been adopted into the popular surgical nomenclature.

Since the first description of the rare forms of hernia with incarceration of the appendix and the first appendectomy, much has been reported about the surgical procedure for hernias and diseases of the appendix. One milestone in the development of appendectomies was the introduction of laparoscopy. Laparoscopic appendectomy, first performed in 1982 by Kurt Semm in Kiel,4 has, after initial skepticism, become a routine procedure.

The new developments in the area of laparoscopic hernia treatment that also have their origin in the 1980s have become part of surgical routine as well. Total extraperito-neal hernia repair (TEP) and transperitoneal preperitoneal hernia repair (TAPP) are commonplace today, though still the object of comparative scientific studies.5,6 In addition to inguinal repair, the repair of femoral hernias via TEP is also a procedure that has been described before.7

The incidence of an appendix in a hernia, in other words the Amyand and the de Garengeot hernia, has been described by Ryan 19378 as well as by Lester 19799 with 0.13% of all appendectomies. Carey finds an incidence of 1%10among his relatively small patient cohort. Both authors, however, describe the predestination of postmenopausal, adipose women to the femoral hernia symptom whose incidence is not described separately from inguinal hernia. Considering the ratio of femoral to inguinal hernias, however, a negligibly low incidence can be assumed.

Femoral hernias account for approximately 3% of all hernias, and the hernial orifice is located in the region of the lacuna vasorum on the medial side of the femoral vein below the inguinal ligament.11 The differential diagnosis of the Amyand hernia includes various urological symptoms in males (testicular torsion, acute hydrocele, testicular tumor, and acute epididymitis), while the differential diagnosis of the de Garengeot hernia that almost exclusively affects females is adnexitis in addition to the inguinal hernia, a varix node or ectasia of the Vena saphena magna, lipomas or other soft tissue tumors, lymphomas (both neoplastic or inflammatory) and hypostatic abscesses in retroperitoneal processes.

The confirmed preoperative diagnosis of both of these rare types of hernias is difficult and therefore usually incumbent on the surgeon during the procedure. Nevertheless, some literature references to the preoperative diagnosis by means of sonography12 or computed tomography13 are available.

Herein, we describe the first case of a de Garengeot hernia treated by simultaneous laparoscopic appendectomy and TAPP.

CASE REPORT

Patient Presentation and History

The patient was a 38-year-old female who was admitted to the emergency room of the surgical clinic due to a nonreducible protrusion in the right lower abdomen that was tender to pressure. At the same time, she was suffering from diffuse pain across the entire lower abdomen. The otherwise empty history only includes 2 regular births 16 and 18 years earlier. The patient noticed a protrusion in the right inguinal region 6 months earlier. It receded spontaneously on several occasions. She states that she was experiencing a pulling pain in the right inguinal region when lifting heavy loads. Two days before she presented in the emergency room, the protrusion in the inguinal region reappeared. Since then, it neither disappeared spontaneously nor was it reversible through application of pressure. The pain was bearable under administration of over-the-counter analgesics. The emergency admission was suggested by the patient's general practitioner.

Examination

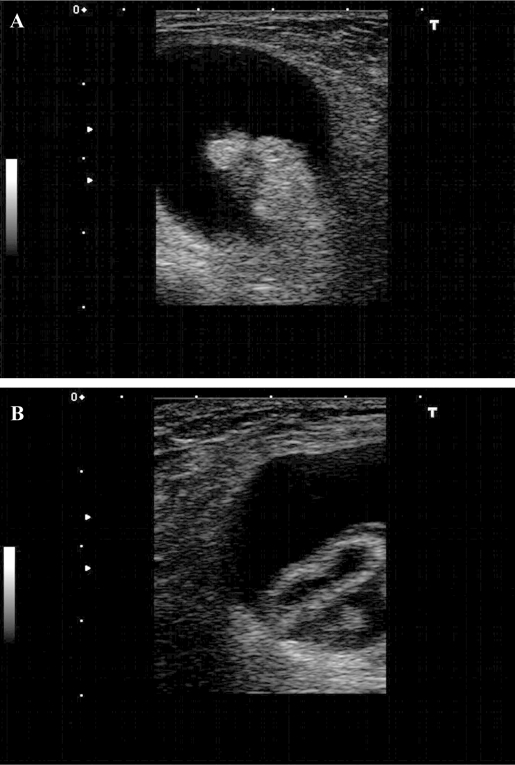

The 38-year-old patient was in good general and nutritional status. Her body weight of 65kg with a height of 172cm was within the regular range. The clinical examination revealed a dense elastic swelling in the right inguinal region with pronounced tenderness to pressure and a diameter of approximately 6cm. The abdomen was soft with regular peristalsis. Sonography revealed a cystic space-occupying lesion containing echo-dense material (Figure 1). Neither the color-coded imaging nor the power Doppler revealed any evidence of perfusion within the echo-dense material. A sample biopsy of the cystic formation yielded bloodstained fluid. The laboratory test results revealed mild leukocytosis of 11090 thousand/μL the C-reactive protein was within the regular range. The body temperature was not elevated.

Figure 1.

Findings of a space-occupying mass in the right inguen revealed by sonography. The cross-section shows a liquid formation with echo-dense content (A). The power Doppler does not provide evidence of vascularization. The longitudinal section (B) reveals an echo-dense exterior structure and an echo-free inner space.

Surgery

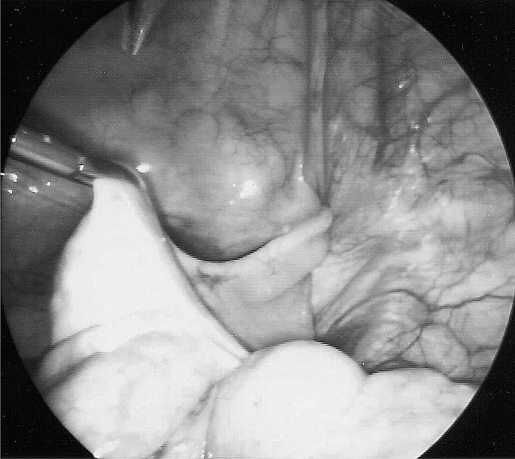

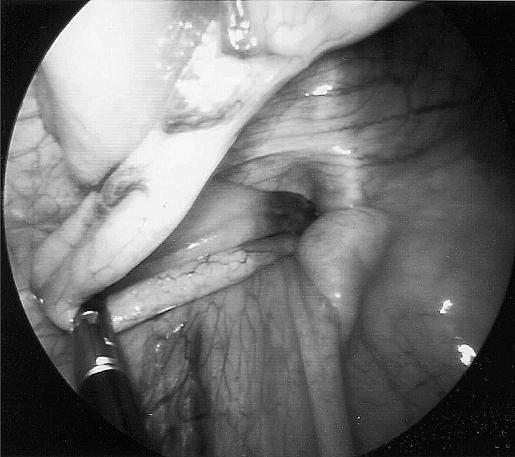

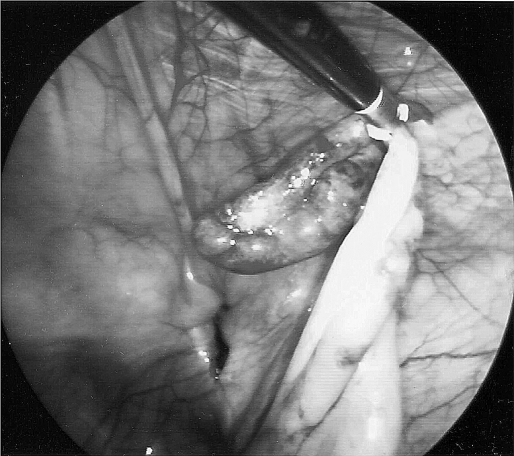

The indication for surgery was established based on suspected greater omentum incarceration in an inguinal hernia. Due to the absence of perfusion as revealed by power Doppler and regular intestinal function, an intestinal incarceration was determined to be unlikely. We decided on a transabdominal laparoscopic exploration. The procedure was carried out with the patient under general anesthesia, and the patient was monitored in a standard manner. She received antibiotic prophylaxis with a single dose of 1500 mg of cefuroxime. An optic trocar (12 mm) and a 5-mm and a 10-mm working trocar were introduced following infraumbilical mini laparotomy. The capnoperitoneum was created by maintaining a CO2 pressure of 12 mm Hg. The exploration of the abdominal cavity revealed that liver, gallbladder, stomach, and the small and large intestine were regular. The hernial orifices on the left side were closed. On the right side, a femoral hernia was observed at a typical location below the inguinal ligament and on the medial side of the external iliac vein. The distal appendix was herniated and incarcerated as a result of the narrow hernial gap (classified as F2 according to Schumpelick et al)14 (Figure 2). At the same time, the appendix was torqued 1½ times around its own axis. By pulling at the base and simultaneous fixation of the peritoneum, we succeeded in gradually repositioning the appendix into the abdomen (Figures 3 and 4). The distal appendix was bloated with inflamed alterations (Figure 5); perfusion was interrupted as a result of incarceration and torsion. We subsequently performed a laparoscopic appendectomy, where both the mesoappendix and the appendix were closed using a resorbable clip, followed by the typical treatment using a transabdominal preperito-neal patch (TAPP) with a 10x15-cm piece of polypropylene mesh. The peritoneum was closed above the mesh by using continuous sutures.

Figure 2.

Initial findings within the scope of laparoscopy, revealing the twisted and incarcerated appendix.

Figure 3.

Gradual repositioning of the appendix through longitudinal pull and de-rotation.

Figure 4.

The incarcerated tip of the appendix with thickened mesoappendix is treated last.

Figure 5.

After the repositioning is complete, the inflammatory vascular infiltration and thickening can be seen clearly. The hernial canal of the femoral hernia is now clearly visible in the background.

The postoperative development was complication free. The patient was allowed to drink immediately after surgery and was able to eat unrestricted amounts of a normal diet as of day one after surgery. The use of analgesics was limited to 500 mg of paracetamol and 20 drops of met-amizole. During hospitalization, the patient was treated with low-molecular heparin. She was discharged from the hospital on day 6 after surgery. On the occasion of a follow-up examination at our outpatient clinic 14 days after surgery, the patient was completely symptom free.

The histological examination of the appendix revealed chronically relapsing appendicitis and evidence of disturbed circulation at the tip of the appendix.

DISCUSSION

Compared with the anatomically adjacent inguinal hernia, the femoral hernia is a rarer type of hernia.11 In 40% ofcases, the patients only present for surgery at the stage of incarceration.15 Most often, the hernial contents consist of small intestine. However, in addition to parts of the greater omentum, it can also consist of parts of the primary female genitals, due to the predilection of the female sex.

As individual case reports compiled in recent decades show, the appendix presenting as hernial sac contents is a rare diagnosis.2,9,16–20 Undoubtedly the most uncommon case of a de Garengeot hernia was described by Breitenstein et al,21 who were able to document a case on the left side of the body of a patient. However, other hernial contents of inflammatory origin that imitate appendicitis have been described. For example, Greenberg and Arnell22 describe a diverticular abscess within a left-sided hernia.

The uncommonness of the findings is therefore undisputed. However, establishing the diagnosis is difficult. The clinical differentiation with other inflammatory processes is impossible. The clinical signs of appendicitis are usually absent. In our case, the use of sonography did not yield a confirmed preoperative diagnosis as is described for an individual case in the literature.12 Even our sonography-guided puncture did not yield conclusive findings. On the one hand, the rarity of the diagnosis poses a challenge; on the other hand, no procedure other than CT23 can be awarded high specificity with respect to the symptoms. Based on the pronounced clinical symptoms in our case, the indication for surgical treatment was established and the expansion of the noninvasive diagnostic procedures suspended.

For lack of ileal symptoms, we decided to use laparos-copy. In this respect, TAPP provides the decisive criterion for diagnostic laparoscopy which is attributed equally in the evaluation of the interstitium compared with laparotomy.24 In our opinion, the extraperitoneal procedure (TEP) described by Ferzli et al25 for treating incarcerated hernias is questionable because the evaluation of the intraabdominal situation, and in particular the repositioned hernial contents, is impossible. In their publication, Ferzli et al25 forego the evaluation of the hernial sac contents and the intraabdominal findings. They justify this omission by referring to the publication by Ishihara et al,26 who observed a normalization of the intestinal mobility and vitality during laparoscopic hernial reposition procedures combined with inguinal repair in 6 patients. Sagger et al27 describe one case of TEP repair with simultaneous laparoscopic appendectomy via separate access paths.

These authors' argument in favor of TEP is the integrity of the parietal peritoneum as a natural barrier between implanted materials and a potential source of infection. Based on this argumentation, every further abdominal procedure would be possible without affecting the mesh, but Ferzli et al25 describe one case of mesh infection following TEP. This clearly shows the limitations of the procedure, because no artificial materials should be implanted in the presence of an extensive infection. Even pronounced accompanying peritonitis without the macroscopic opening of the peritoneum should be grounds for the exclusion of implanting foreign materials. The TAPP procedure provides the possibility to inspect the intraabdominal situs before treating the hernia and to select an alternative procedure, if necessary. In our case, findings of pus or even necrosis would have made the further laparoscopic procedure with respect to the treatment of the hernia nonviable. In such a case, the possible alternative consists of a 2-stage procedure by means of laparoscopic hernia repair when the patient is free of acute symptoms or the open inguinal access for the initial treatment. The risk to the patient caused by infection of the implanted mesh must never be underestimated. The implantation of foreign material in patient-appropriate sizes is a key issue. Polypropylene mesh with good biocompatibility is available in different sizes and shapes. Anatomically adapted mesh facilitates the closure of hernial gaps. In particular, the risk of potential infection is an open question. In the literature, different studies27–29 provethe feasibility of implantation of synthetic grafts even in infected wounds. Jones and Jurkovich30 see a complication rate of 80% in their study involving the implantation of a polypropylene mesh into an infected wound. Their work, however, deals with patients with massive abdominal soft tissue infections or even fasciitis. In the case of a potential infection, as in our case, the implantation is certainly defensible, especially since the secondarily closed peritoneum fulfils a protective function. The critical individual decision of the surgeon in any given case is of utmost importance, however.

The intention-to-treat variant by means of laparoscopy for incarcerated hernias is questionable, irrespective of the selection of the procedure. Although open surgery is still considered the standard procedure,11 several current reports reveal a different outlook.31 In addition to social and subjective benefits to the patient, the possible intraoperative observations certainly represent a positive factor. Laparotomy in case of unclear findings of the hernial contents is not an option.

Although the proportion of laparoscopic treatment of hernias reported in a Danish study32 conducted in 2001 was 5%, this figure likely increased significantly as a result of the higher number of surgeons experienced in performing laparoscopies and the greater acceptance of the procedure. While the implantation of foreign material is still considered the standard procedure in current inguinal hernia surgeries (Lichtenstein et al, TEP, TAPP),5,32 it remains possible to forgo the use of these materials in open surgery, which might be a significant benefit for the healing process in patients suffering from fulminate infections.

The laparoscopic treatment of a femoral hernia by means of TAPP has been described7 and corresponds to the surgical procedure involving inguinal hernias. Since the procedure was first described 25 years ago, laparoscopic appendectomy has become an increasingly routine procedure, depending on the surgeon's laparoscopic skills.7,33 Our laparoscopic procedure centainly documents an extention of the current possibilites. As individual surgeries, neither the TAPP treatment of a femoral hernia nor the laparoscopic appendectomy poses a major challenge to an experienced surgeon. Nevertheless, we believe our presentation is justified based on the first description of the combination of illnesses and the surgical procedure we selected to treat them. Rene Jacques Croissant de Garengeot—whose name is largely absent in the medical literature—will be grateful after his first description.

CONCLUSION

The rare form of the de Garengeot hernia is generally suitable for laparoscopic treatment (TAPP). However, the procedure is limited by the expansion of the infection originating from the appendix. Compared with the TEP procedure, The TAPP method that we use has the benefit of diagnostic laparoscopy. In case of a widespread infection, the option to switch to open, inguinal surgery or 2-stage treatment is available. The risk to the patient as a result of the use of mesh in the presence of an infetion can therefore be avoided.

References:

- 1. Hutchinson R. Amyand's hernia. J R Soc Med. 1993;86(2):104–105 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Akopian G, Alexander M. De Garengeot hernia: appendicitis within a femoral hernia. Am Surg. 2005;71(6):526–527 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hiatt JR, Hiatt N. Amyand's hernia. N Engl J Med. 1988; 318(21):1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983;15(2):59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schmedt CG, Sauerland S, Bittner R. Comparison of endoscopic procedures vs Lichtenstein and other open mesh techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(2):188–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wake BL, McCormack K, Fraser C, Vale L, Perez J, Grant AM. Transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) vs totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(1):CD004703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yalamarthi S, Kumar S, Stapleton E, Nixon SJ. Laparoscopic totally extraperitoneal mesh repair for femoral hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2004;14(6):358–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ryan WJ. Hernia of vermiform appendix. Ann Surg. 1937; 106:135–13917857011 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lester R, Bourke JB. Strangulated femoral hernia containing appendices. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1979;24(2):102–103 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carey LC. Acute appendicitis occurring in hernias: a report of 10 cases. Surgery. 1967;61(2):236–238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hachisuka T. Femoral hernia repair. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(5):1189–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Filatov J, Ilibitzki A, Davidovitch S, Soudack M. Appendicitis within a femoral hernia: sonographic appearance. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(9):1233–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zissin R, Brautbar O, Shapiro-Feinberg M. CT diagnosis of acute appendicitis in a femoral hernia. Br J Radiol. 2000;73(873):1013–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schumpelick V, Treutner KH, Arlt G. Classification of inguinal hernias [in German] Chirurg. 65(10):877–879, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schumpelick V. Hernien. 4th ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Thieme; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barbaros U, Asoglu O, Seven R, Kalayci M. Appendicitis in incarcerated femoral hernia. Hernia. 2004;8(3):281–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D'Ambrosio N, Katz D, Hines J. Perforated appendix within a femoral hernia. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186(3):906–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fitzgerald E, Neary P, Conlon KC. An unusual case of appendicitis. Ir J Med Sci. 2005;174(1):65–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Isaacs LE, Felsenstein CH. Acute appendicitis in a femoral hernia: an unusual presentation of a groin mass. J Emerg Med. 2002;23(1):15–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kueper MA, Kirschniak A, Ladurner R, Granderath FA, Konigsrainer A. Incarcerated recurrent inguinal hernia with covered and perforated appendicitis and periappendicular abscess: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2007;11(2):189–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Breitenstein S, Eisenbach C, Wille G, Decurtins M. Incarcerated vermiform appendix in a left-sided inguinal hernia. Hernia. 2005;9(1):100–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenberg J, Arnell TD. Diverticular abscess presenting as an incarcerated inguinal hernia. Am Surg. 2005;71(3):208–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fukukura Y, Chang SD. Acute appendicitis within a femoral hernia: multidetector CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30(5):620–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lavonius MI, Ovaska J. Laparoscopy in the evaluation of the incarcerated mass in groin hernia. Surg Endosc. 2000;14(5):488–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferzli G, Shapiro K, Chaudry G, Patel S. Laparoscopic extra-peritoneal approach to acutely incarcerated inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(2):228–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ishihara T, Kubota K, Eda N, Ishibashi S, Haraguchi Y. Laparoscopic approach to incarcerated inguinal hernia. Surg Endosc. 1996;10(11):1111–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saggar VR, Singh K, Sarangi R. Endoscopic total extraperitoneal management of Amyand's hernia. Hernia. 2004;8(2):164–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gilsdorf RB, Shea MM. Repair of massive septic abdominal wall defects with Marlex mesh. Am J Surg. 1975;130(6):634–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McNeeley SG, Jr., Hendrix SL, Bennett SM, et al. Synthetic graft placement in the treatment of fascial dehiscence with necrosis and infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 179(6 pt 1):1430–1434, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones JW, Jurkovich GJ. Polypropylene mesh closure of infected abdominal wounds. Am Surg. 1989;55(1):73–76 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rebuffat C, Galli A, Scalambra MS, Balsamo F. Laparoscopic repair of strangulated hernias. Surg Endosc. 2006; 20(1):131–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bay-Nielsen M, Kehlet H, Strand L, et al. Quality assessment of 26,304 herniorrhaphies in Denmark: a prospective nationwide study. Lancet. 2001;358(9288):1124–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McNeeley SG, Jr., Hendrix SL, Bennett SM, et al. Synthetic graft placement in the treatment of fascial dehiscence with necrosis and infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(6 Pt1):1430–1434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]