Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Hepatic artery chemoembolization (HACE) used to treat neuroendocrine tumors metastatic to the liver has shown both survival benefit and improvement in symptoms. The development of hepatic necrosis after HACE is rare, but the consequences can be devastating. We report the first case of laparoscopic management of extensive hepatic necrosis occurring after HACE.

Case Report:

A 58-year-old man with neuroendocrine tumor metastatic to the liver underwent HACE in addition to medical management. He had undergone previous biliary stenting for biliary obstruction. After HACE was performed via the right hepatic artery, the patient developed sepsis due to right hepatic lobe infarction. Percutaneous drainage and antibiotics were attempted for 2 months, but hepatic debridement was ultimately required due to repeated drain malfunction and septic complications. Laparoscopic necrosectomy was performed with ease and with little blood loss. The patient quickly recovered without any further infectious complications.

Conclusion:

Infected hepatic necrosis resulting from HACE that fails percutaneous management can be successfully managed with laparoscopic necrosectomy. This report adds to the growing evidence that minimally invasive techniques can be used to manage complicated hepatic conditions.

Keywords: Laparoscopic surgery, Hepatic necrosis, Complication, Chemoembolization

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic artery chemoembolization (HACE) has been utilized as part of the treatment of various hepatic tumors. Its use for neuroendocrine tumors metastatic to the liver has resulted in both survival benefit and symptomatic improvement.1 The potential hepatic complications after HACE include liver failure, hepatic abscess or necrosis, portal vein thrombosis, and tumor rupture.

The development of hepatic necrosis after HACE is one of the most severe hepatic complications that has been described. This complication is rare, with fewer than 10 cases reported to date based on a Medline search. Many additional reports exist of hepatic abscess after HACE,1–10 but abscess and necrosis have important distinctions. In contrast to hepatic abscess, hepatic necrosis implies that a significant degree of devitalization of previously normal liver parenchyma occurs, often in a segmental or lobar pattern. Most cases of hepatic necrosis are complicated by infection, particularly involving gram-negative bacteria. The mortality rate of infected hepatic necrosis is approximately 50%.2

Treatment options for infected hepatic necrosis include intravenous antibiotics, percutaneous drainage, and open surgical drainage or liver resection.2 We report the first case of hepatic necrosis after HACE managed definitively with laparoscopic hepatic necrosectomy. This report adds to the growing body of literature supporting the role of minimally invasive surgery in managing a broad array of hepatic conditions.

CASE REPORT

A 58-year-old man presented to an outside facility with abdominal pain and jaundice. The initial workup demonstrated a large mass involving the head and neck of the pancreas and multiple bilobar hepatic masses. Liver biopsy was consistent with metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. An octreotide scan showed evidence of uptake in both the pancreas and liver. The patient was felt to have unresectable pancreatic disease and underwent percutaneous placement of right and left hepatic duct metal endoprostheses to relieve the biliary obstruction.

On presentation to our facility, the patient reported severe right upper quadrant pain and debilitating diarrhea despite pancreatic enzyme replacement. Sandostatin therapy produced little improvement. Surgical resection was not pursued due to portal vein encasement and extensive hepatic tumor burden. HACE was recommended as a palliative procedure.

HACE was performed according to a standard protocol. The initial angiogram demonstrated numerous small lesions throughout the right and left lobes of the liver and normal hepatopedal portal venous flow. Right hepatic artery chemoinfusion was performed with a combination of doxorubicin, mitomycin, and carboplatin in Ethodiol, followed by embolization using starch microspheres.

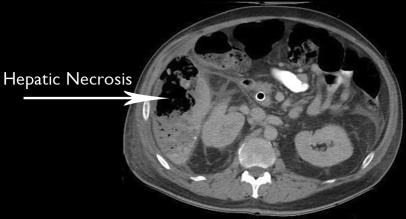

The patient presented 7 days after HACE with severe abdominal pain and signs of sepsis. CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated right hepatic lobe infarction (Figure 1). He also suffered from gram-negative bacteremia. The patient was initially treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics and percutaneous drainage of the liquefied portion of the liver. He was discharged home after approximately 3 weeks with two 12-French pigtail drains in the infarcted area. Over the next several months, he suffered from intermittent episodes of sepsis that usually responded to antibiotic adjustment and drain replacement. Biliary patency was ensured with ERCP to exclude a contribution from biliary obstruction. Due to recurring sepsis and repeated drain malfunction, surgical debridement was undertaken.

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen demonstrating right hepatic lobe infarction.

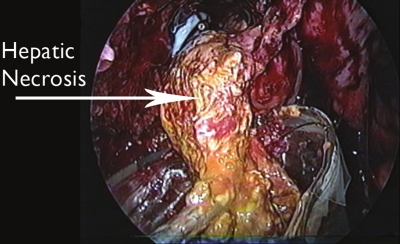

Laparoscopy was undertaken in a standard fashion by using carbon dioxide to maintain pneumoperitoneum. The liver was completely obscured by adhesions involving both the colon and omentum. By following the parietal peritoneum towards the diaphragm, a large cavity containing necrotic hepatic tissue was identified. Most of the necrotic tissue was easily separable from surrounding hepatic parenchyma and was removed using an Endobag (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) (Figure 2). Cultures of the debrided tissue grew Klebsiella pneumoniae. Large sump drains were laid in the cavity following necrosectomy. Blood loss was 100mL and operating time was 75 minutes.

Figure 2.

Necrotic tissue separated from surrounding hepatic parenchyma and being removed using an Endobag (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH).

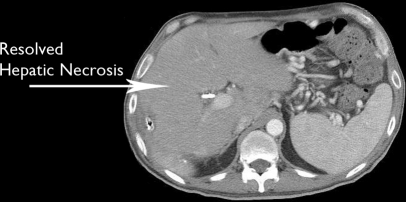

Following hepatic necrosectomy, the patient had complete resolution of fevers. He was discharged home after 5 days, and had no further infectious or wound complications. There was no sign of bile leak. The sump drains were removed after approximately 3 weeks, and repeat imaging demonstrated resolution of the hepatic necrosis and infarct (Figure 3). He remained alive and free of infection 12 months after HACE, although he has had progression of the left hepatic tumor burden.

Figure 3.

Repeat computed tomographic scan of the abdomen, demonstrating resolution of the hepatic necrosis and infarct.

DISCUSSION

Hepatic metastases of neuroendocrine tumors often lead to severe morbidity and mortality due both to hepatic complications and the production of numerous biochemical mediators. HACE and other methods of hepatic cytoreduction have been shown to improve quality of life and survival.1,3 Numerous hepatic complications can accompany HACE, including liver abscess, necrosis, biloma, cholangitis, liver failure, and portal vein thrombosis. Large reviews of HACE report an incidence of hepatic abscess of less than 1%.6,7

Hepatic necrosis has rarely been reported after HACE, which in part may reflect the lack of distinction between abscess and necrosis. Intuitively, a regional therapy such as HACE that devitalizes a segmental or lobar distribution should be considered necrosis, whereas smaller focal areas might be considered abscesses. Several reports have consistently shown bilioenteric communication, biliary stents, or other biliary abnormalities to be the most important predisposing factor for the development of post-HACE liver abscess.2,7–10 Our patient had a pre-existing biliary endoprosthesis, which likely predisposed to infection. We speculate that an additional ischemic insult to the right lobe by portal vein encasement by the primary tumor may have contributed to right lobe necrosis.

Management of hepatic abscess or necrosis after chemoembolization consists of antibiotics and in most cases an attempt at drainage. Small abscesses in stable patients can be managed with antibiotics alone, but patients with severe sepsis or bacteremia should undergo drainage. In many cases this can be performed percutaneously and in refractory cases with laparoscopy or laparotomy. By comparison, the management of hepatic necrosis is often more complex because of both the severity of associated sepsis and the risk of liver failure due to destruction of uninvolved parenchyma. Treatment of hepatic necrosis includes antibiotics along with drainage, debridement, or resection of necrotic liver.

Our report is the first to describe a minimally invasive approach to hepatic necrosis. The current case was well suited for necrosectomy because the 3-month delay since onset had resulted in a large degree of liquefaction, which in turn facilitated separation of the devitalized tissue from normal liver. If early surgical intervention was required before liquefaction was established, there might have been a higher risk of bleeding and possibly the need for lobar or segmental resection.

Laparoscopic liver operations are a relatively new option available in the treatment of liver conditions. The advantages of laparoscopic techniques are multiple and include decreased postoperative pain, shorter length of stay and more rapid return of normal activity. In patients such as the one described here, with infectious complications superimposed on hepatic metastases, the morbidity of laparotomy can be overwhelming due to malnutrition, ascites, and poor functional reserve. In this setting, the benefits of the minimally invasive hepatic approach are compounded.

CONCLUSION

Infected hepatic necrosis is a rare but devastating complication of hepatic artery chemoembolization. Biliary-enteric communication, indwelling biliary stents or prior biliary manipulation may increase the risk of this complication. Minimally invasive surgical techniques, as described here, add an important management option, and should be considered in select cases when antibiotics and percutaneous drainage have failed.

Contributor Information

Talar Tejirian, Department of Surgery, Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA..

Anthony Heaney, Department of Medicine.Division of Endocrinology, UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA.; David Geffen/UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Stephen Colquhoun, Department of Surgery.Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA.; David Geffen/UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California, USA.

Nicholas Nissen, Department of Surgery.Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA.; David Geffen/UCLA School of Medicine, Los Angeles, California, USA.

References:

- 1. Sullivan KL. Hepatic artery chemoembolization. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:145–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Baere T, Roche A, Amenabar JM, et al. Liver abscess formation after local treatment of liver tumors. Hepatology. 1996; 23:1436–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinreich DM, Alexander HR. Transarterial perfusion of liver metastases. Semin Oncol. 2002;29:136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sakamoto I, Iwanaga S, Nagaoki K, et al. Intrahepatic biloma formation (bile duct necrosis) after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. AJR. 2003;181:79–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gagner M, Rogula T, Selzer D. Laparoscopic liver resection: benefits and controversies. Surg Clin North Am. 2004;84:451–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tarazov PG, Polysalov VN, Prozorovskij KV, Grishchenkova IV, Rozengauz EV. Ischemic complications of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in liver malignancies. Acta Radiol. 2000; 41:156–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang SF, Ko CW, Chang CS, Chen GH. Liver abscess formation after transarterial chemoembolization for malignant hepatic tumor. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1115–1118 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim W, Clark TW, Baum RA, Soulen MC. Risk factors for liver abscess formation after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:965–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song SY, Chung JW, Han JK, et al. Liver abscess after transcatheter oily chemoembolization for hepatic tumors: incidence, predisposing factors, and clinical outcome. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:313–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eckel F, Lersch C, Huber W, Weiss W, Berger H, Schulte-Frohlinde E. Multimicrobial sepsis including Clostridium perfringens after chemoembolization of a single liver metastasis from common bile duct cancer. Digestion. 2000;62:208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]